Key Points

Combining undetectable ctDNA and complete response by PET-CT at C4D15 was associated with extended PFS in FL and DLBCL cohorts of ELM-2.

ctDNA detection may be prognostic of patient outcomes with odronextamab and may form the basis of response-guided treatment paradigms.

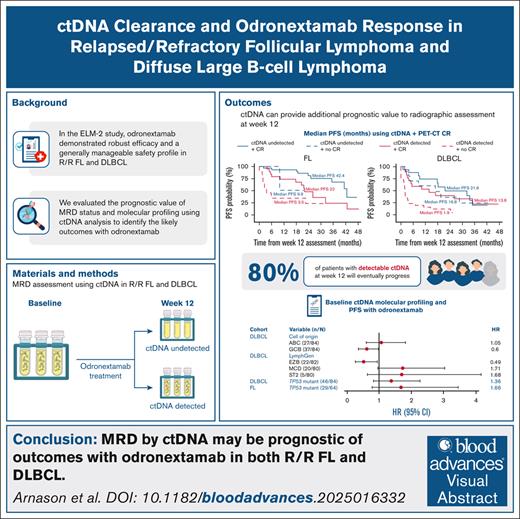

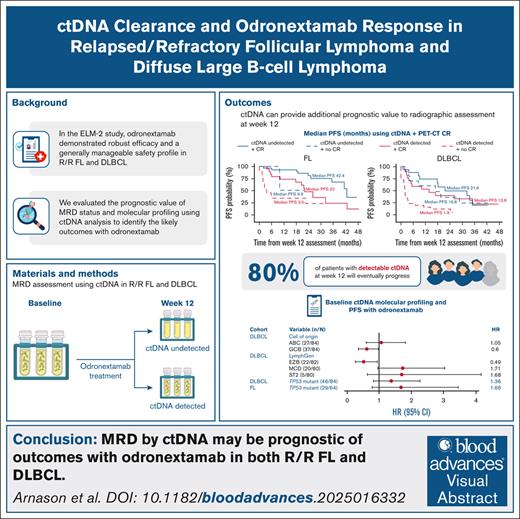

Visual Abstract

Odronextamab, a CD20×CD3 bispecific antibody, demonstrated robust efficacy and durable responses, with a generally manageable safety profile, in patients with relapsed/refractory follicular lymphoma (FL) and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) in the phase 2 ELM-2 study. This exploratory analysis evaluated the prognostic value of minimal residual disease (MRD) status and tumor molecular profiles, based on circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) analysis, for determining patient outcomes in ELM-2. Baseline and on-treatment ctDNA samples were used for MRD evaluation (AVENIO Oncology Assay Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma test); baseline ctDNA samples were also used for molecular profiling. At data cutoff (24 March 2025), the cycle 4, day 15 (C4D15) biomarker population with available ctDNA results comprised 60 patients with FL and 77 patients with DLBCL. Undetectable ctDNA at C4D15 was associated with prolonged progression-free survival (PFS) in the FL (hazard ratio [HR], 0.31; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.14-0.67) and the DLBCL cohorts (HR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.24-0.75). Combining undetectable ctDNA with achievement of positron emission tomography-computed tomography complete response at C4D15 was associated with extended PFS in both cohorts. Among patients with progressive disease per Lugano criteria, most had detectable ctDNA at C4D15 (FL, 15/19; DLBCL, 28/35). In the DLBCL cohort, LymphGen analysis by ctDNA showed that the MCD subtype trended toward shorter PFS, whereas the EZB subtype trended toward longer PFS, compared with the rest of the cohort. MRD by ctDNA may be prognostic of outcomes with odronextamab in FL and DLBCL and could form the basis of response-guided treatment paradigms. This trial is registered at www.ClinicalTrials.gov as #NCT03888105.

Introduction

Bispecific antibodies are important treatment options for B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (B-NHL).1 Odronextamab is a human CD20×CD3 bispecific antibody that simultaneously engages cytotoxic T cells and malignant B cells, which can result in the killing of malignant cells.2-4 Odronextamab has been evaluated in heavily pretreated patients with B-NHL in the phase 1 ELM-1 and phase 2 ELM-2 studies.4-6 In ELM-2, odronextamab monotherapy demonstrated robust efficacy and durable responses in patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) follicular lymphoma (FL; objective response rate, 80.5%; median duration of response, 22.6 months) and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL; objective response rate, 52.0%; median duration of response, 10.2 months), with a generally manageable safety profile (most common grade ≥3 treatment-emergent adverse events were neutropenia [DLBCL, 26%; FL, 32%] and anemia [DLBCL, 23%; FL, 12%]).5,6

Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) is a promising noninvasive tool that facilitates the detection of small residual tumor masses, or minimal residual disease (MRD), with several potential clinical applications.7,8 Pretreatment ctDNA levels in patients with DLBCL have shown prognostic value in both frontline (hazard ratio [HR], 2.6; P = .007) and salvage (HR, 2.9; P = .01) treatment settings; 24-month event-free survival was significantly poorer in patients with high vs low ctDNA levels.9 Similarly, in patients with R/R DLBCL undergoing autologous stem cell transplantation, MRD identified using immunoglobulin high-throughput sequencing of preautologous stem cell transplantation apheresis stem cell samples was associated with 5-year progression-free survival (PFS) of 13% vs 53% for MRD negativity.10 MRD also has potential as a means to assess early treatment efficacy and monitor response11; however, data supporting the prognostic value of MRD following treatment with bispecific antibodies are limited, particularly in FL, and further discussion around assay sensitivity and the most informative time point is needed.12-15

Assessment of ctDNA also allows limited molecular characterization of tumor cells; for example, ctDNA can be used to define cell of origin (COO)11 and LymphGen classification in DLBCL,16 as well as identify mutational variants in patients with FL and DLBCL.17,18 Specific DLBCL subtypes, determined using tissue biopsies, have previously been associated with high-risk disease, including activated B-cell–like MCD and N1 subtypes,19-21 whereas TP53 mutations have been associated with shorter survival in newly diagnosed B-NHL.22-24

We present results from an exploratory analysis of MRD and molecular profiling, based on ctDNA analysis from patients enrolled in the ELM-2 study, to evaluate their association with outcomes after odronextamab treatment. We also present a concordance analysis of molecular profiling results based on ctDNA samples and tumor biopsies.

Methods

Study design, patients, and treatment

ELM-2 is an ongoing phase 2, open-label, multicohort, multicenter study of odronextamab monotherapy for adult patients with R/R B-NHL, including specific cohorts for FL and DLBCL (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03888105). Full details of the study design are published5,6; information on eligibility criteria and treatment is summarized in the supplemental Methods.

The protocol was approved by relevant institutional review boards and ethics committees at each site. The study was conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent.

MRD assessment

Whole blood samples for MRD assessment were collected in 10-mL Streck tube Cell-Free DNA blood collection tubes, shipped to central laboratories on the day of collection, and processed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Both plasma and buffy coat-containing cell pellets were stored. Samples were collected at baseline, at the first response assessment (week 12 [cycle 4, day 15 (C4D15)] ± 10 days), and for patients with complete response (CR), at each time point when computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans were performed.

In the FL cohort, the collection of germ line DNA was included as a protocol amendment in June 2021. Patients enrolled before June 2021 could provide germ line samples, if they remained in the study following this amendment.

MRD status was analyzed by measuring ctDNA in plasma, with samples prepared using the AVENIO Oncology Assay Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Test (Roche Sequencing Solutions Pharma Services, Research Use Only), performed by Roche as a commercial service.25 ctDNA analysis was based on the cancer personalized profiling by deep sequencing (CAPP-Seq) technique.9,26 Samples were prepared using a target-enrichment-based next-generation sequencing workflow, with the capture panel tracking more than 400 regions enriched in DLBCL- and FL-associated variants, and libraries sequenced on Illumina sequencers (supplemental Figure 1; supplemental ctDNA Data). For longitudinal ctDNA tracking, variant calling was performed on the baseline ctDNA sample to identify reporter variant candidates; variants were removed from the reporter candidate list if they were detected in germ line DNA from the cell pellet or peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Reporter variants were monitored in on-treatment plasma samples using an empirical Monte-Carlo P value statistical algorithm, as described previously.9 ctDNA levels were reported in mutant molecules per milliliter, with “ctDNA undetected” reported when the P value for variant allele frequency was >.005.27 A maximum of 50 ng input cell-free DNA (cfDNA) was used. In accordance with country regulations, cfDNA samples were not collected from patients in China, who were excluded from analyses.

Molecular profiling

Plasma samples and tumor biopsies collected at baseline (C1D1) were used for molecular profiling, COO classification,28 and LymphGen classification using cfDNA sequencing. Tumor biopsy samples were prepared from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded blocks or RNAlater solution–stabilized tissue (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Samples were sent to IQVIA Laboratories Genomics, and RNA and DNA were dual-extracted. DNA whole-genome sequencing (WGS) and RNA sequencing (RNAseq) of tumor biopsies were performed on Illumina sequencers. WGS was performed with 2 × 150 base pair (bp) paired-end reads and 320 million reads per lane. RNAseq was performed using the TruSeq RNA Exome kit with 2×50 bp paired-end reads and 40 million reads per lane. Patients with paired tumor and normal tissue sequencing were included in the WGS data set. Tumor biopsies collected >90 days before C1D1 were excluded to account for possible mutational and expression changes before starting odronextamab treatment.

LymphGen classification of DLBCL samples was conducted on ctDNA and tumor biopsy samples, as described previously.29 LymphGen prediction using ctDNA was based on genetic variants in the capture panel and BCL2/BCL6 translocation data, whereas prediction using WGS was based on somatic variants, BCL2/BCL6 translocation, and copy number variant. Somatic variants were identified using Sentieon, a commercial software implementing TNscope30; translocations of BCL2 and BCL6 were assessed using Parliament231; and copy number variation (CNV) was estimated using CNVkit,32 to aid in identifying the A53 subtype.

Clinical outcome

The clinical outcome of interest in this analysis was PFS by independent central review. Disease assessments (using CT/MRI and positron emission tomography [PET]) were performed at screening, week 12, then every 8 weeks in the first year, every 12 weeks in the second year, and per protocol at safety and extended follow-up visits.

Statistical analyses

Efficacy analyses included all patients who received at least 1 dose of odronextamab (overall population). Patients with a progression event before C4D15 or without a C4D15 response assessment were excluded from the C4D15 overall population. The biomarker population comprised all patients with C1D1 ctDNA samples. For PFS analyses by molecular profile, all patients with a valid baseline ctDNA or baseline tumor biopsy result were analyzed (baseline biomarker population). For PFS analyses by MRD status, patients without a valid C4D15 ctDNA result or whose disease progressed before C4D15 response assessment were excluded. As this biased the biomarker population toward patients who were still receiving treatment at C4D15, PFS estimation started from C4D15.

All analyses reported here were exploratory, and this study was not powered for statistical testing of these end points. Kaplan-Meier curves were generated to compare PFS stratified by ctDNA detection at C4D15. PFS was compared between ctDNA detected vs ctDNA undetected using a log-rank test, and HRs and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated from Cox proportional hazard models. The association between PFS and ctDNA detection at C4D15 was compared with that of PFS and major molecular response (MMR) criteria (≥2.5-log decrease in ctDNA from baseline9). Additionally, the association between disease progression and MRD status at C4D15 was evaluated using a competing risk model, in which progressive disease (PD) was the outcome event of interest and death due to non-PD–related causes was a competing event. The cumulative incidence was estimated using the subdistribution hazard model for each event type, and HRs were estimated using the cause-specific Cox regression model.

Multiple Cox regression analysis of MRD status at C4D15 was performed, adjusting for known baseline predictors of PFS (for DLBCL: International Prognostic Index score, COO, and time since last treatment; for FL: Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index score and time since last treatment),33-36 to confirm if undetectable ctDNA was independently associated with prolonged PFS. Concordance analysis was performed to compare the molecular characteristics using ctDNA and tumor biopsies. Confusion matrices were presented for COO (nongerminal center B cell [non-GCB] vs GCB or unclassified), LymphGen classification (rest of cohort vs MCD, EZB, BN2, and ST2), MYD88 (wild-type vs mutant), and TP53 (wild-type vs mutant) to assess concordance between the 2 profiling methods. Associations between PFS and the presence of TP53 mutations (in FL and DLBCL), MYD88 mutations, COO, and LymphGen classification (all in DLBCL only) at baseline were also evaluated.

Results

Patient populations

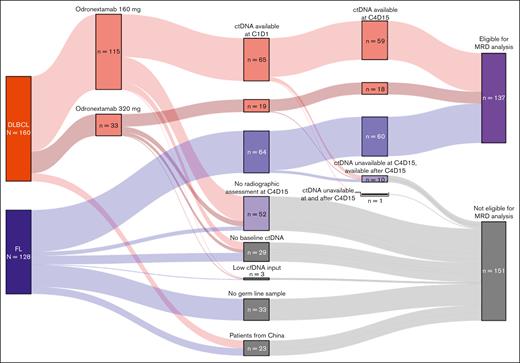

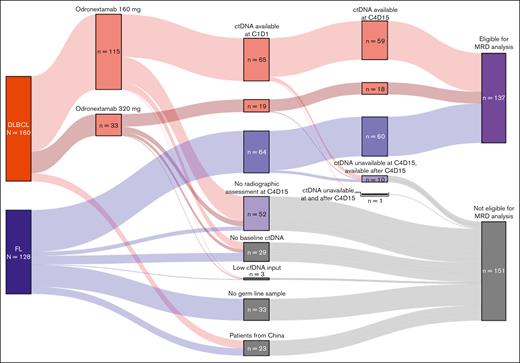

Data cutoffs were 15 August 2024, for efficacy analyses and 24 March 2025, for ctDNA analyses. A Sankey plot of the overall and biomarker populations is provided in Figure 1.

Sankey plot of patient disposition. For most patients, exclusion from MRD analyses was due to a lack of opportunity for week 12 response assessment. Patients from China were also excluded. Some patients with FL did not have a germ line sample collected and could not be analyzed. A minority of patients who were eligible did not have a week 1 sample collected, and 3 patients failed analysis (all due to low cfDNA input).

Sankey plot of patient disposition. For most patients, exclusion from MRD analyses was due to a lack of opportunity for week 12 response assessment. Patients from China were also excluded. Some patients with FL did not have a germ line sample collected and could not be analyzed. A minority of patients who were eligible did not have a week 1 sample collected, and 3 patients failed analysis (all due to low cfDNA input).

Baseline ctDNA samples were collected from 65 patients with R/R FL and 86 patients with R/R DLBCL. By June 2021, approximately half of patients with FL had been enrolled, and 33 of 128 patients (25%) did not have germ line samples. ctDNA was detected in 148 of 151 patients tested at baseline (biomarker population at C1D1: FL, n = 64; DLBCL, n = 84). Three patients had undetectable ctDNA at baseline, likely due to the low quantities of input cfDNA available (DLBCL, n = 2 [8.68 ng and 12.2 ng]; FL, n = 1 [10.75 ng]).

At C4D15, 111 patients with FL (China, n = 9) and 107 patients with DLBCL (China, n = 8) had the opportunity for radiographic response assessment and were eligible for analyses. Of these, ctDNA samples were collected at weeks 1 and 12 from 60 patients with FL (54.1%) and 77 with DLBCL (72.0%); excluding patients from China, collection rates were 58.8% and 79.4%, respectively.

Baseline characteristics were generally similar between the overall and biomarker populations; patients were heavily pretreated and had highly refractory disease (supplemental Table 1).

PFS in the C4D15 overall and biomarker populations

Among patients in the FL cohort eligible for analysis at C4D15, median PFS from C4D15 was 22.6 months in the overall population (n = 111; median follow-up, 35.5 months) and 35.2 months in the biomarker population (n = 60; median follow-up, 29.9 months; supplemental Figure 2A). In the DLBCL cohort, median PFS from C4D15 was 5.4 months in the overall population (n = 107; median follow-up, 36.4 months) and 8.5 months in the biomarker population (n = 77; median follow-up, 36.7 months; supplemental Figure 2B). PFS from C4D15 was similar between the 160-mg and 320-mg once-weekly cohorts in both the overall and biomarker populations (supplemental Figure 3).

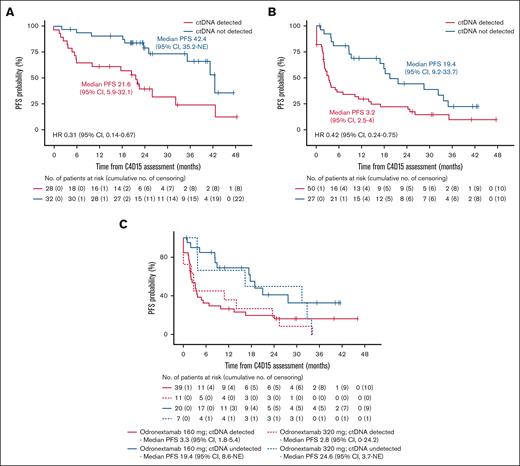

Association between MRD status at C4D15 and PFS

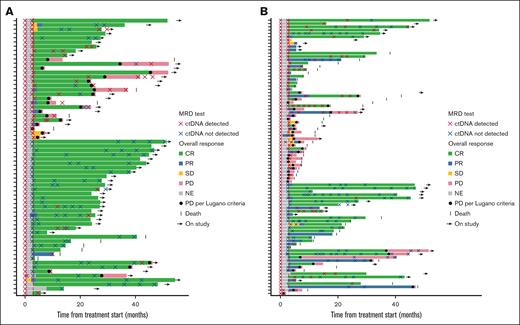

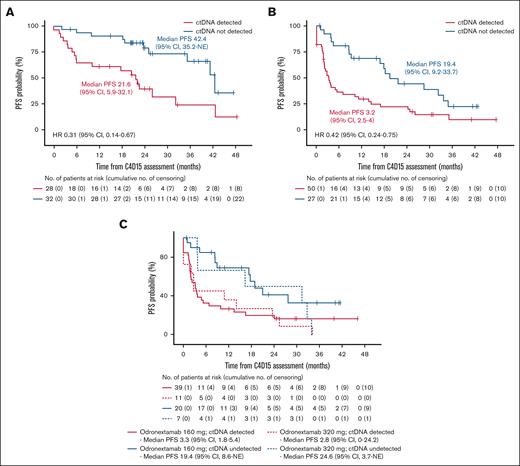

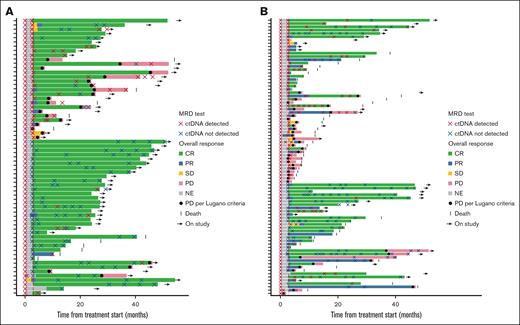

The association between MRD status at C4D15 and PFS was assessed in biomarker populations of the FL and DLBCL cohorts. In FL, 32 of 60 patients (53.3%) had undetectable ctDNA at C4D15, and 39 of 64 patients (60.9%) achieved undetectable ctDNA during the study. Patients with undetectable ctDNA at C4D15 had longer PFS than those with detectable ctDNA (median, 42.4 vs 21.6 months, respectively; HR, 0.31; 95% CI, 0.14-0.67; Figure 2A). Among 23 patients with FL who had PD per Lugano criteria,37 19 had detectable ctDNA at C4D15, and 15 never had undetectable ctDNA (Figure 3A). Thus, detectable ctDNA at C4D15 was prognostic of progression in 19 of 23 patients (82.6%). There were 14 cases of MRD reversal: 7 patients with detectable ctDNA at C4D15 had undetectable ctDNA at one or more later time points, and 7 patients experienced the reverse.

Kaplan-Meier estimate of PFS according to MRD status at C4D15. FL cohort (A), DLBCL cohort (B), and DLBCL 160 mg and 320 mg once-weekly cohorts (C) in the C4D15 biomarker population, with PFS estimated from C4D15 response assessment date. Median PFS is presented in months. NE, not estimable.

Kaplan-Meier estimate of PFS according to MRD status at C4D15. FL cohort (A), DLBCL cohort (B), and DLBCL 160 mg and 320 mg once-weekly cohorts (C) in the C4D15 biomarker population, with PFS estimated from C4D15 response assessment date. Median PFS is presented in months. NE, not estimable.

Swimmer plots of MRD status and outcome in the biomarker population. FL cohort (A) and DLBCL cohort (B). In the FL cohort (n = 64), 6 patients without a C4D15 sample but with a C1D1 sample and at least 1 on-treatment sample are shown; 1 patient had a ctDNA sample collected but no valid results. In the DLBCL cohort (n = 84), 8 patients without a C4D15 sample but with a C1D1 sample and at least one on-treatment sample are shown; 2 patients had a ctDNA sample collected but no valid results. NE, not estimable; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease.

Swimmer plots of MRD status and outcome in the biomarker population. FL cohort (A) and DLBCL cohort (B). In the FL cohort (n = 64), 6 patients without a C4D15 sample but with a C1D1 sample and at least 1 on-treatment sample are shown; 1 patient had a ctDNA sample collected but no valid results. In the DLBCL cohort (n = 84), 8 patients without a C4D15 sample but with a C1D1 sample and at least one on-treatment sample are shown; 2 patients had a ctDNA sample collected but no valid results. NE, not estimable; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease.

In DLBCL, 27 of 77 patients (35.1%) had undetectable ctDNA at C4D15, and 35 of 84 patients (41.7%) achieved undetectable ctDNA during the study. Patients with undetectable ctDNA at C4D15 had longer PFS than those with detectable ctDNA (median, 19.4 vs 3.2 months, respectively; HR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.24-0.75; Figure 2B). Similar trends were observed in the different odronextamab dose cohorts (Figure 2C). Among 35 patients with DLBCL who had PD per Lugano criteria,37 28 had detectable ctDNA at C4D15, 3 did not have a C4D15 test but had detectable ctDNA before C4D15, and 26 never achieved undetectable ctDNA (Figure 3B). Therefore, detectable ctDNA at C4D15 was prognostic of progression in 28 of 35 patients (80.0%) with DLBCL. There were 11 cases of MRD reversal: 6 patients with detectable ctDNA at C4D15 later achieved undetectable ctDNA, and 4 experienced the reverse; 1 additional patient who did not have a C4D15 ctDNA sample experienced MRD reversal at a later time point.

Comparison of ctDNA levels per MMR criteria9 and absolute posttreatment MRD status to predict PFS

Relative decreases in ctDNA levels per MMR criteria9 and absolute posttreatment MRD status were analyzed to determine the optimal early biomarker end point for prolonged PFS. Undetectable ctDNA at C4D15 had a lower HR compared with MMR in both FL (HR, 0.31 [95% CI, 0.14-0.67] vs 0.46 [95% CI, 0.22-0.99], respectively) and DLBCL (HR, 0.42 [95% CI, 0.24-0.75] vs 0.56 [95% CI, 0.33-0.95]; supplemental Figure 4). Thus, absolute MRD status at C4D15 was selected to predict PFS.

A competing risk analysis was conducted to distinguish between deaths due to PD and deaths due to other possibly unrelated causes. Detectable ctDNA was associated with PD or death due to PD (FL: HR, 0.12; DLBCL: HR, 0.27), but not death due to other reasons (supplemental Figure 5).

Undetectable ctDNA as an independent predictor of PFS

Multiple Cox regression analyses showed that, after adjusting for time since last treatment and the Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index score, undetectable ctDNA at C4D15 was still independently associated with prolonged PFS in patients with FL (HR, 0.31; supplemental Figure 6A). Similarly, in DLBCL, after adjusting for time since last line of treatment, International Prognostic Index score, and COO, undetectable ctDNA at C4D15 was still independently associated with prolonged PFS (HR, 0.34; supplemental Figure 6B).

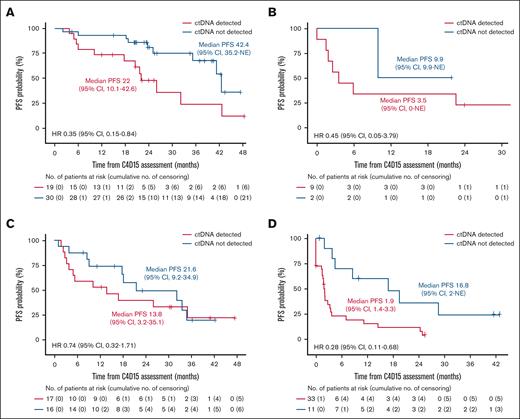

Association between combined PET-CT and MRD status at C4D15 and PFS

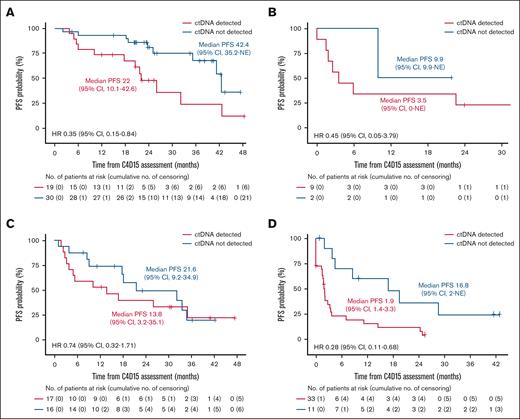

In the FL cohort, 49 of 60 patients had a radiographic CR at C4D15, and within this subset, PFS was longer in patients with undetectable vs detectable ctDNA at C4D15 (median, 42.4 vs 22.0 months, respectively; HR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.15-0.84; Figure 4A). A similar trend was observed in 11 patients with FL without a CR at C4D15 (HR, 0.45; 95% CI, 0.05-3.79; Figure 4B). In the DLBCL cohort, 33 of 77 patients had a radiographic CR at C4D15, with a trend toward longer PFS in patients with CR who had undetectable vs detectable ctDNA (HR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.32-1.71; Figure 4C). Similarly, among 44 patients without a CR, PFS was longer in those with undetectable vs detectable ctDNA (median, 16.8 vs 1.9 months, respectively; HR, 0.28; 95% CI, 0.11-0.68; Figure 4D).

Kaplan-Meier estimate of PFS according to ctDNA status in patients with and without CR at C4D15. FL cohort with CR (A) and without CR (B); DLBCL cohort with CR (C) and without CR (D) in the C4D15 biomarker population, with PFS estimated from C4D15 response assessment date. Median PFS is presented in months.

Kaplan-Meier estimate of PFS according to ctDNA status in patients with and without CR at C4D15. FL cohort with CR (A) and without CR (B); DLBCL cohort with CR (C) and without CR (D) in the C4D15 biomarker population, with PFS estimated from C4D15 response assessment date. Median PFS is presented in months.

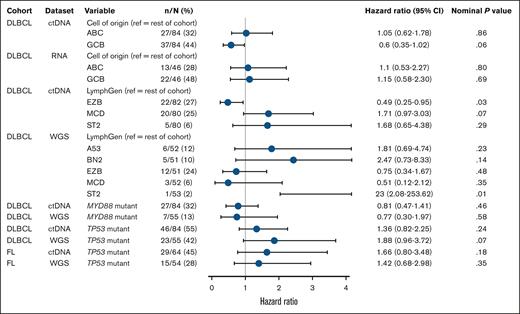

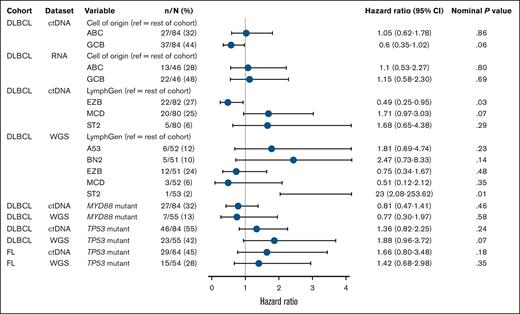

Association between molecular profiling, using ctDNA or tumor biopsies, and PFS

In a separate analysis, we evaluated the association between tumor molecular profiles and PFS, as well as concordance between ctDNA and tumor biopsy molecular profiles. Tumor biopsies were collected from 54 patients with FL and 55 with DLBCL; ctDNA (C1D1 and C4D15) and tumor biopsy sample sets are shown in supplemental Figure 7. Molecular profiling results based on ctDNA samples and tumor biopsies showed variable concordance (supplemental Figure 8).

Due to higher ctDNA sample availability compared with RNAseq of tumor biopsies, COO determination (DLBCL cohort) was possible for 82 patients by ctDNA and 64 by RNAseq. In the univariate Cox regression analysis, there were no significant differences in PFS between activated B-cell–like and GCB-like subtypes of DLBCL, with generally consistent findings by ctDNA and RNAseq (Figure 5). Kaplan-Meier curves of PFS by COO using ctDNA began to separate after 12 months, with a trend toward longer survival in patients with GCB, whereas no separation was observed using RNAseq of tumor biopsies (supplemental Figure 9).

Univariate Cox regression analysis of molecular characteristics associated with PFS according to ctDNA and tumor biopsy sample sets, in FL and DLBCL cohorts of the baseline biomarker population. References for LymphGen comparisons included patients with a single LymphGen subtype, those with multiple subtypes, and those classified as “other.” For patients with multiple subtypes, if one of those subtypes was the same as the comparator subtype, then that patient was excluded from the reference group (hence the varying N numbers). ABC, activated B cell; ref, reference.

Univariate Cox regression analysis of molecular characteristics associated with PFS according to ctDNA and tumor biopsy sample sets, in FL and DLBCL cohorts of the baseline biomarker population. References for LymphGen comparisons included patients with a single LymphGen subtype, those with multiple subtypes, and those classified as “other.” For patients with multiple subtypes, if one of those subtypes was the same as the comparator subtype, then that patient was excluded from the reference group (hence the varying N numbers). ABC, activated B cell; ref, reference.

LymphGen subtype results for DLBCL were available for 82 patients by ctDNA and 53 by tumor biopsy, reflecting the ease of collection and low failure rate with ctDNA. With ctDNA or tumor biopsy, 49% to 56% of patients were able to have a single subtype assigned, and the EZB subtype was identified in a similar proportion of patients (27% by ctDNA and 24% by tumor biopsy). The MCD subtype by ctDNA (n = 20; 25% of population) trended toward shorter PFS (HR, 1.71; 95% CI, 0.97-3.03; Figure 5; supplemental Figure 10). Among these patients, 10 had a MYD88 mutation and 10 were wild-type, and HRs were similar between groups, indicating that MYD88 status was not independently associated with PFS. Tumor biopsy identified 3 patients (6%) as MCD, with variable outcomes. The ST2 subtype was identified in 6% of patients by ctDNA and in 1 patient by tumor biopsy. Confusion matrices revealed low concordance between ctDNA and tumor biopsy (supplemental Figure 8).

Mutational analyses using ctDNA identified TP53 as the most frequently mutated gene in patients with FL (ctDNA, 67%; WGS, 29%) and DLBCL (ctDNA, 72%; WGS, 46%; supplemental Figure 11). Concordance between ctDNA and WGS results for TP53 mutation status was lower in the FL cohort (71.8%; 15.6% mutated and 56.2% wild-type) than in the DLBCL cohort (79.5%; 32.4% mutated and 47.1% wild-type). Irrespective of sample type, TP53 mutations were consistently associated with a trend toward shorter PFS in FL (ctDNA: HR, 1.66; WGS: HR, 1.42) and DLBCL (ctDNA: HR, 1.36; WGS: HR, 1.88).

Discussion

Noninvasive methods for assessment of response to therapy and longitudinal monitoring are important to tailor B-NHL treatment approaches to individual patients. This exploratory analysis from ELM-2 evaluated the utility of ctDNA to determine MRD status and molecular profiling in patients treated with a bispecific antibody, and is among the first to assess ctDNA in patients with R/R FL.

At C4D15 of odronextamab treatment, 53.3% of patients in the FL cohort and 35.1% in the DLBCL cohort had undetectable ctDNA, which was associated with prolonged PFS in both cohorts. These results contribute to growing evidence supporting MRD assessment as a prognostic tool in B-NHL.10,12-15,38-40 Furthermore, this is the first molecular marker that is prognostic of PFS following treatment with a T-cell–engaging bispecific antibody. MRD status at C4D15 retained its prognostic value when combined with PET-CT CR status in both cohorts. Detectable ctDNA was associated with shorter PFS in patients with FL who achieved CR at C4D15 and was able to identify patients with DLBCL who had prolonged PFS without achieving a CR at C4D15. Therefore, MRD status might further differentiate the risk of disease progression within radiographic response categories in both FL and DLBCL cohorts. MRD status may provide additional prognostic value over PET-CT response by identifying patients who could benefit from additional treatment, even after achieving a CR, as part of a response-guided treatment approach.

Direct comparisons with other studies are challenging due to varying time points, interventions, lines of therapy, and assays.14,15,41,42 In patients with R/R FL receiving epcoritamab, 77 of 128 patients (60%) had available MRD data, and 49 of 77 (64%) had undetectable ctDNA at C3D1, which was associated with longer PFS.14 These analyses used the clonoSEQ assay that requires a baseline tumor biopsy or ctDNA to calibrate trackable B-cell–receptor rearrangements (clonotype). ctDNA detection using clonoSEQ is therefore restricted to the captured clonotype and further limited in FL and DLBCL by high rates of somatic mutations.8 Additionally, the number of patients with detectable ctDNA at baseline or undetectable ctDNA at C3D1 and PD was unclear. Notably, in 26 patients with R/R FL, the CD19×CD3 bispecific antibody AZD0486 obtained undetectable ctDNA in 92% of those with a radiographic CR at the same time point (12 weeks) using the phased variant enrichment and detection sequencing (PhasED-Seq) platform.41 In the ELM-2 FL cohort, 1 patient had undetectable ctDNA at baseline, likely due to low ctDNA input (10.75 ng), and 78.9% of patients whose disease progressed had detectable ctDNA at C4D15, with a median follow-up duration of >2 years. This is noteworthy since FL is considered incurable. The fact that ctDNA was still detectable in 19 of 49 patients with FL who achieved CR at C4D15, which was associated with shorter PFS, suggests that MRD status provides additional clinical utility beyond radiographic response and could identify patients who may benefit from additional therapies, instead of standard treatment or observation only.

In the DLBCL cohort, 2 patients did not have valid ctDNA results at baseline, and detectable ctDNA at C4D15 was prognostic of PD in 28 of 35 patients (80.0%). In contrast, a correlative study using the clonoSEQ assay in patients with previously untreated DLBCL reported trackable rearrangements in 86% of patients using a baseline tumor biopsy and only 37% using ctDNA. Furthermore, all 11 patients with undetectable ctDNA subsequently progressed.43 In another broader patient population with R/R large B-cell lymphoma (LBCL), 45.4% of patients receiving epcoritamab had undetectable ctDNA (clonoSEQ), and undetectable ctDNA at C3D1 was associated with longer PFS and overall survival.15 Other analyses in the LBCL setting have reported that high baseline ctDNA levels (above the median) were associated with shorter PFS after glofitamab treatment (HR, 2.19).42 MRD assessment at earlier time points may be as prognostically informative as at C4D159,10 and this is being evaluated as part of the odronextamab phase 3 OLYMPIA trial series (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers: NCT06091254, NCT06097364, NCT06091865, NCT06230224, and NCT06149286).44-48 In addition, earlier time points will allow for the inclusion of higher-risk patients who experience earlier PD, who could not be included here.

The limit of detection of a ctDNA assay depends on the number of variants being tracked, the input amount of cfDNA, and the background error rate. Despite this potential limitation, we observed high clinical relevance of the CAPP-Seq assay in our study, with detectable ctDNA at C4D15 in 78.9% (15/19) of patients with PD at any time in the FL cohort and in 80.0% (28/35) of patients in the DLBCL cohort.

Concordance between ctDNA and tumor biopsies in identifying COO, LymphGen classification, and mutational status was limited. LymphGen classification was developed for patients newly diagnosed with DLBCL and ideally uses a combination of mutations, rearrangements, and CNVs.29 Here, classification was demonstrated in ∼60% of third-line or later patients, with an EZB prevalence of ∼25% by both ctDNA and tumor biopsy, similar to those observed with newly diagnosed patients.29 However, more MCD patients were identified by ctDNA than by tumor biopsies, which may be partly explained by higher detection rates of MYD88 mutations in ctDNA. These discrepancies are likely related to differences in technology, with ctDNA including only a subset of mutations but with higher coverage, and limited rearrangement data. The favorable PFS with EZB vs MCD by ctDNA was consistent with previous findings21 and will be further evaluated in follow-up studies.

Previous studies have reported poor prognosis in patients with non-GCB and high-grade B-cell lymphoma receiving chemoimmunotherapy.19,20,33,49 In the current analysis, the efficacy of odronextamab was similar regardless of COO, which was consistent with the results of other studies involving bispecific antibodies.12 However, the use of ctDNA to determine gene rearrangements appears to be more limited at this time and requires further investigation.

Concordance in identifying TP53 using ctDNA vs tumor biopsy in FL was lower than in DLBCL. As sequencing coverage depth is 2 logs deeper for ctDNA than tumor biopsy, we expected to observe greater precision with ctDNA. TP53 mutation status appeared to negatively influence PFS, although data were limited. Poor survival outcomes have previously been reported in patients with newly diagnosed B-NHL with TP53 mutations.22-24 The role of TP53 mutation status in patients with B-NHL treated with odronextamab will be examined in the ongoing OLYMPIA trials. Further analysis of bispecific antibody efficacy across molecular subgroups with larger sample sizes is warranted to determine their potential for patient selection.

Limitations of this analysis include its exploratory nature, the small number of patients per molecular subgroup, and the absence of MRD analyses before C4D15. An additional limitation was the low detection of MYC, BCL2, and BCL6 rearrangements using ctDNA. In the ELM-2 study, changes in MRD status (ctDNA detected to undetected, or undetected to detected) after C4D15 were uncommon, and this may be due to the R/R nature of the study population. Sample collection is ongoing and may show re-emergence of detectable ctDNA before radiographic progression. Further evaluation of the duration of MRD response in earlier lines of treatment, the prognostic value of MRD as a platform, and assay-specific sensitivity analyses as they relate to outcome are needed and will be conducted in the ongoing OLYMPIA trials. Continuous patient monitoring may also allow detection of potential resistance mutations (eg, CD20 mutations) that arise during treatment.

In conclusion, the use of ctDNA as a noninvasive approach for molecular profiling in B-NHL appears feasible. Our analysis shows that combining undetectable ctDNA with PET-CT CR status at C4D15 was associated with prolonged PFS in both FL and DLBCL cohorts. MRD status by ctDNA could be a valuable tool to monitor odronextamab treatment outcomes and form the basis of response-guided treatment paradigms in the future.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients, their families, the ELM-2 study team, all other investigators, and all investigational site members involved in this study, especially during the challenging times of the COVID-19 pandemic. Medical writing support was provided by Ashvanti Valji, Ida Darmawan, and Lucy Carrier of Oberon, a division of OPEN Health Communications (London, United Kingdom), and funded by Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc, in accordance with Good Publication Practice (https://www.ismpp.org/gpp-2022).

Authorship

Contribution: J.E.A., M.M., S.L., and D.T. participated in the acquisition of clinical data from their study sites and the interpretation of the data; D.S., W.T., Y.O.Z., K.K., N.T.G., and A.L. performed the data analyses; V.J. contributed to the data analyses and interpretation of the data; S.A., H.M., and A.C. participated in the design of the study, data analysis, and interpretation of the data; J.B.-V. oversaw biomarker strategy implementation, sample collection, data analyses, and interpretation of the data; and all authors contributed to the development of the first and subsequent drafts and approved the final submission draft of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.E.A. reports speaker’s fee from Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. M.M. reports consultancy for Bayer, Genentech, GM Biosciences, Johnson & Johnson, Pharmacyclics, Roche, and Seattle Genetics; research funding from Bayer, Genentech, GM Biosciences, Immunovaccine Technologies, Johnson & Johnson, Pharmacyclics, Roche, and Seattle Genetics; honoraria from ADC Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), Celgene, Epizyme, Genentech, IMV Therapeutics, Johnson & Johnson, Kite, Pharmacyclics, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Roche, Pfizer, Seattle Genetics, and Takeda; and membership on an entity’s board of directors or advisory committees for Allogene, Genentech, Genmab, and Merck. S.L. reports consultancy for AstraZeneca, BeiGene, BMS, Incyte, Janssen, Kite, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Roche, Sobi, and Takeda. D.T. reports consultancy and/or an advisory role for Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc, AbbVie, BeiGene, Immunovant, and Gilead; and travel, accommodation, or other expenses from BeiGene. D.S., W.T., Y.O.Z., K.K., N.T.G., A.L., H.M., A.C., and J.B.-V. hold stock or stock options for and are employees of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. S.A. and V.J. hold stock or stock options for and are former employees of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

The current affiliation for V.J. is Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Ridgefield, CT. The current affiliation for S.A. is Beam Therapeutics, Cambridge, MA.

Correspondence: Jurriaan Brouwer-Visser, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc, 777 Old Saw Mill River Rd, Tarrytown, NY 10591; email: jurriaan.brouwer@regeneron.com.

References

Author notes

Qualified researchers may request access to study documents (including the clinical study report, study protocol with any amendments, blank case report form, and statistical analysis plan) that support the methods and findings reported in this article. Individual anonymized participant data will be considered for sharing: (1) once the product and indication have been approved by major health authorities (eg, the US Food and Drug Administration, European Medicines Agency, Pharmaceutical and Medical Devices Agency) or development of the product has been discontinued globally for all indications on or after April 2020 and there are no plans for future development, (2) if there is legal authority to share the data, and (3) there is not a reasonable likelihood of participant reidentification. Requests for data may be submitted to https://vivli.org/.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.