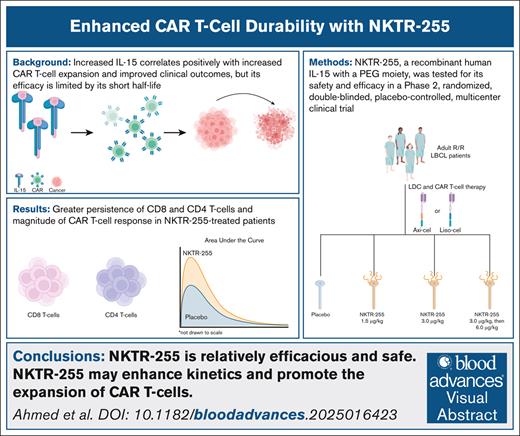

Visual Abstract

TO THE EDITOR:

Autologous chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy transformed the treatment of relapsed/refractory (R/R) large B-cell lymphomas (LBCL).1 Lymphodepleting chemotherapy (LDC) followed by CD19-targeted CAR T cells yields significant response rates in patients with R/R LBCL.2,3 However, durable responses are challenging, as most patients fail to achieve remission and/or eventually relapse.1 Patients who achieve a complete response (CR) at 6 months are more likely to remain in CR at and 2 years after CAR T-cell therapy.4-6 Therefore, an intervention to improve CR rates may translate into improved event-free survival.

Prior work suggests that higher levels of interleukin-15 (IL-15) in peripheral blood are correlated positively with improved clinical responses within the first month after CAR T-cell infusion.7-9 Recent research demonstrated that IL-15–armored CAR T cells increased CAR T-cell expansion and intratumoral survival.10 Its short half-life constrained previous efforts to harness the antitumor effects of IL-15.11 NKTR-255, a recombinant human IL-15 attached to a polyethylene glycol moiety, was developed as a novel receptor agonist that preserves the biological function of IL-15.12-14 NKTR-255 administration following CAR T-cell infusion results in CAR and CD8 T-cell expansion in patients with R/R B-cell malignancies.14,15 Altogether, these studies support exogenous IL-15 supplementation to enhance the efficacy of CAR T-cell treatment.

Here, a final analysis of 15 patients is presented due to financial prioritization by the sponsor.

This phase 2, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, multicenter study compared the CR rate at 6 months (CRR6) of NKTR-255 to placebo treatment, following CD19 CAR T-cell therapy. Adult patients with R/R LBCL who received standard lymphodepleting chemotherapy (LDC) and their physician’s choice of 1 of 2 US Food and Drug Administration–approved CAR T-cell products (axicabtagene-ciloleucel [axi-cel] or lisocabtagene-maraleucel [liso-cel]) were eligible; the full inclusion and exclusion criteria are included in the supplemental Appendix. Patients were randomized 1:1:1:1 to receive a placebo or NKTR-255 at 1.5 μg/kg, 3.0 μg/kg, or 3.0 μg/kg in cycle 1, then 6.0 μg/kg for cycle 2 and beyond (C2+). The treatment was administered 14 days after CAR T-cell infusion and then every 21 days until the primary efficacy assessment (supplemental Figure 1A). Further method details are in the supplemental Appendix.

All patients provided informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and applicable Good Clinical Practice guidelines. An independent data safety and monitoring committee oversaw the trial conduct.

Thirty-six patients were screened between March and December 2023. Fifteen patients were randomized as follows: 4 to the placebo, 5 to 1.5 μg/kg NKTR-255, 3 to 3.0 μg/kg NKTR-255, and 3 to 3.0 μg/kg in cycle 1, 6.0 μg/kg NKTR-255 for C2+ (supplemental Figure 1B). Group baseline characteristics were well-balanced (supplemental Table 1). Twelve (80%) patients received axi-cel and 3 (20%) received liso-cel before NKTR-255 administration. All patients received at least 1 NKTR-255 dose, and most (6/11, 55%) in the NKTR-255 group completed all 7 cycles.

Infusion-related reactions and fever were reported in 2 (18%) and 3 (27%) of the 11 patients who received NKTR-255, respectively. All infusion-related reaction and fever events were grade 1 or 2 and resolved within 24 hours. Decreased neutrophil (5/11, 46%), platelet (2/11, 18%), and lymphocyte (2/11, 18%) counts were the most common grade 3 or greater NKTR-255–related adverse events (AEs) that occurred in more than 1 patient (supplemental Table 2). NKTR-255 administration 14 days after CAR T-cell infusion did not cause or worsen any cases of cytokine release syndrome or immune cell effector–associated neurotoxicity syndrome .

One patient experienced a grade 5 AE of Guillain-Barré syndrome. The complete case description is in the supplemental Appendix. An independent data monitoring committee found no causal relationship between the administration of NKTR-255 and the AEs.

The CRR6 was 73% (8/11 patients) and 50% (2/4 patients) for the NKTR-255 and placebo groups, respectively (Table 1). Investigator-reported conversions from stable disease or partial response to a CRR6 occurred in 2 of 8 patients (25%) in the NKTR-255 group compared to 0 of 2 (0%) patients in the placebo group. Based on investigator assessment, the CRR6 was 80% (8/10 patients) and 50% (2/4 patients) for the NKTR-255 and placebo groups, respectively. At the data cutoff, no patients in either group relapsed.

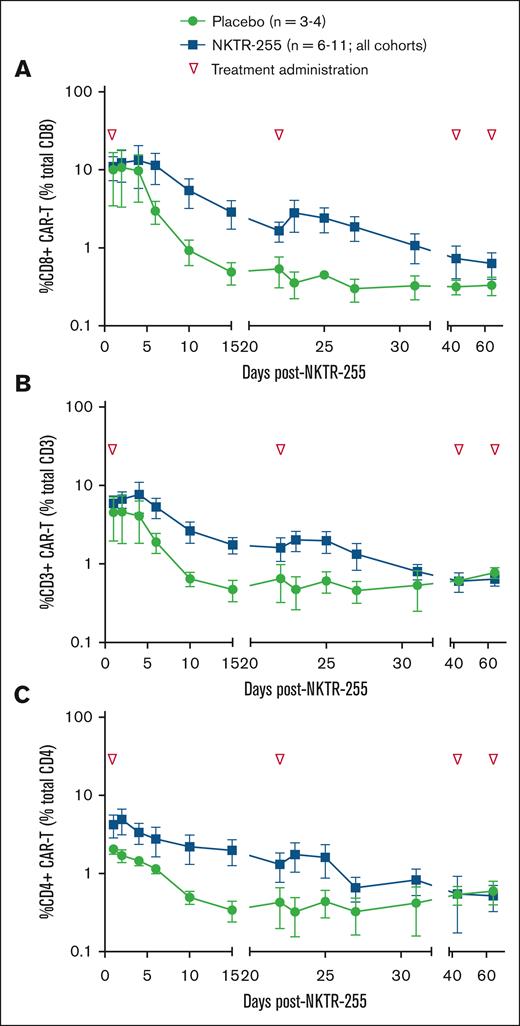

All patients who received NKTR-255 had detectable CAR T cells in their blood during the first month after CAR T-cell infusion. Following NKTR-255 administration on day 14, CD8 CAR T-cell persistence was measured as the percentage of total CD8 T cells. NKTR-255–treated patients maintained higher CD8 persistence levels (Figure 1A); the mean percentage of CD8 CAR T cells was 5.8 times greater in NKTR-255–treated patient samples than in placebo samples 15 days after NKTR-255 administration. In trough measurements on the first day of cycles 3 and 4, CD8 CAR T cells remained elevated in NKTR-255–treated patients compared to the placebo group.

Expansion of CAR T cells following 1 to 3 cycles of NKTR-255. Flow cytometry measurement of patient CAR T cells in the blood after infusion. Persistence of (A) CD8 CAR T cells as a percentage of total CD8 T cells. (B) CD3 CAR T cells as a percentage of total CD3 T cells. (C) CD4 CAR T cells as a percentage of total CD4 T cells. Data are presented as percentages ± SEM by days post-NKTR-255 treatment. Green symbol, placebo; blue symbol, NKTR-255; and inverted triangle, NKTR-255 administration. SEM, standard error of the mean.

Expansion of CAR T cells following 1 to 3 cycles of NKTR-255. Flow cytometry measurement of patient CAR T cells in the blood after infusion. Persistence of (A) CD8 CAR T cells as a percentage of total CD8 T cells. (B) CD3 CAR T cells as a percentage of total CD3 T cells. (C) CD4 CAR T cells as a percentage of total CD4 T cells. Data are presented as percentages ± SEM by days post-NKTR-255 treatment. Green symbol, placebo; blue symbol, NKTR-255; and inverted triangle, NKTR-255 administration. SEM, standard error of the mean.

Like CD8 T cells, CD4 CAR T cells demonstrated a slower blood clearance rate in NKTR-255–treated patients, evidenced by a 5.8-fold and twofold difference between NKTR-255– and placebo-treated patients after 1 and 2 treatment cycles, respectively (Figure 1C). Unlike CD8 T cells, no difference in CD4 CAR T-cell levels at trough collections was observed in cycles 3 and 4.

The area under the curve (AUC) was calculated to understand better the differences in the proportional magnitude of the CAR T-cell response between NKTR-255–treated and placebo-treated patients. The AUC was 2.1-times greater in the NKTR-255–treated than in placebo-treated patients.

Given the role of IL-15 in leukocyte chemotaxis, serial serum samples for chemokines, cytokines, and other soluble proteins were evaluated. Transient increases in monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, interleukin-6, and macrophage inflammatory protein-1 beta were observed in the peripheral blood of NKTR-255–treated patients (supplemental Figure 5), suggesting that lymphocytes were driven into tissues.

Patients who relapse following CAR T-cell therapy have a poor prognosis, with a median overall survival of 8 months from the first treatment.16 Current research efforts focus on improving CAR T-cell expansion, persistence, and efficacy, driven by the correlation between expansion and response durability.17,18 This phase 2, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, multicenter study in R/R LBCL adult patients who received CD19-directed CAR T-cell therapy suggests that, NKTR-255 is relatively efficacious and safe and may promote CAR T-cell expansion.

Blinded independent central review and investigator-reported efficacy assessment reported greater CRR6 in patients treated with NKTR-255 than those in the placebo group. NKTR-255 administration after CAR T-cell infusion did not result in any new or worsening cytokine release syndrome or immune cell effector–associated neurotoxicity syndrome events, which are common CAR T-cell therapy–related toxicities.19,20 The most common NKTR-255–associated AEs were grade 3 and 4 neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and lymphopenia,14 and 1 patient experienced grade 5 Guillain-Barré syndrome. No causal relationship was identified between NKTR-255 and the AE. However, this event may signal that further safety discussions are needed.

NKTR-255 enhanced CAR T-cell kinetics, demonstrated by improved CD8 CAR T-cell AUC0-15 in the NKTR-255 combination arms. Our findings are consistent with preclinical work that reported significantly improved CAR T-cell survival and accumulation in the blood and tissues, resulting in more tumor shrinkage and prolonged therapeutic response.21 NKTR-255 administration increased monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 and macrophage inflammatory protein-1 beta levels, chemokines secreted by activated T cells. An expected increase in endogenous natural killer and CD8+ cell frequencies was observed after NKTR-255 administration.

Small cohort sizes limit this study. However, bias was minimized through the trial design and use of blinded independent central review for the primary efficacy assessment.

In summary, this is the first report to suggest that the exogenous cytokine NKTR-255 may be a safe and efficacious treatment for promoting CAR T-cell expansion. Further studies are warranted to explore the clinical benefits of NKTR-255 as an adjuvant to CAR T-cell therapy. This study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov as #NCT05664217.

Acknowledgments: The authors thank the patients, their families, and the investigators who participated in this study. This study was conducted through a clinical collaboration agreement with The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX and Nektar Therapeutics, San Francisco, CA. Jaime S. Horton, a medical writer supported by funding from Nektar Therapeutics, and Danielle Jamison, a technical writer at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, provided drafts and editorial assistance to the authors during preparation of this manuscript.

J.D. received support through National Cancer Institute grant R35 CA210084.

Contribution: A.M.Q.M., Z.H.L., and M.A.T. conceived and designed the study; and all authors contributed to writing and editing the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: S.A. received research support for clinical trials from Nektar, Merck, Xencor, Chimagen, Genmab, KITE/Gilead, Janssen, and Caribou; is a member of the scientific advisory committee of Chimagen; serves on the data safety monitoring board for Myeloid Therapeutics; and is a consultant for ADC Therapeutics and KITE/Gilead Sciences Inc. J.D. has consulted for Rivervest, bluebird bio, Vertex, and HcBiosciences; has equity-ownership in WUGEN Therapeutics and Magenta Therapeutics; received research support from MacroGenics, Bioline, and Incyte; and received additional support from the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society Specialized Center of Research Program. C.J.T. received research funding from Juno Therapeutics/ Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS) and Nektar Therapeutics; serves on advisory boards for Caribou Biosciences, T-CURX, Myeloid Therapeutics, ArsenalBio, Cargo Therapeutics, and Celgene/BMS Cell Therapy; has served on ad hoc advisory boards/consulting (last 12 months) for Nektar Therapeutics, Century Therapeutics, Legend Biotech, Allogene, Sobi, Syncopation Life Sciences, Prescient Therapeutics, Orna Therapeutics, and IGM Biosciences; and holds stock options in Eureka Therapeutics, Caribou Biosciences, Myeloid Therapeutics, ArsenalBio, and Cargo Therapeutics. D.M. has received honoraria from Janssen, Fosun Kite Biotechnology; served in a consulting or advisory role at Adaptive Biotechnologies, Juno/Celgene, Pharmacyclics, Janssen; received research funding from Pharmacyclics, Novartis, Roche/Genentech, Kite, a Gilead company, Adaptive Biotechnologies, Alimera Sciences, Precision Biosciences, Adicet Bio; and holds a patent with Pharmacyclics supporting ibrutinib for cGVHD (no royalty claim). S.D. holds a consulting or advisory role with Kite/Gilead, BMS, and Incyte; and has received research funding from Kite/Gilead. M.-A.P. received honoraria and consulting fees from BMS, Cellectar, Ceramedix, Juno, Kite, MustangBio, Garuda Therapeutics, Novartis, Pluto Immunotherapeutics, Rheos, Seres Therapeutics, Smart Immune, Thymofox, Synthekine, and other fees from Juno and Seres. J.E. has served on speakers' bureaus for BMS and Gilead. C.D. holds stock and other ownership interests in Gilead Sciences and OverT Therapeutics; has a consulting or advisory role in Seagen, BMS Millennium, Roche/Genentech, Janssen, MEI Pharma, Trillium Therapeutics, Astex Pharmaceuticals, and FATE Therapeutics. M.A.T., J.Z., A.M.Q.M., Z.H.L., H.X., Y.L., S.C., and C.F. are shareholders at Nektar Therapeutics. C.C.-L. declares no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Sairah Ahmed, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1515 Holcombe Blvd, Houston 77030, TX; email: sahmed3@mdanderson.org.

References

Author notes

Original data are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author, Sairah Ahmed (sahmed3@mdanderson.org).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.