Key Points

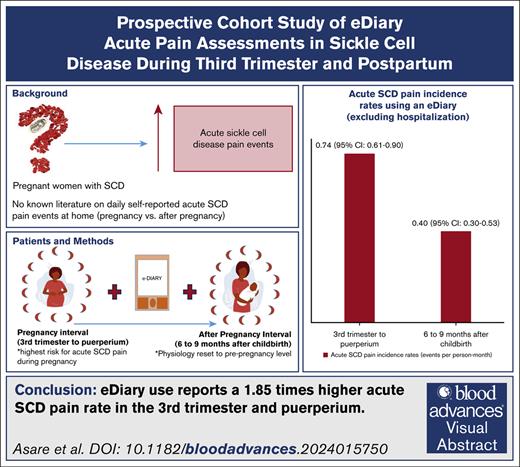

Using an eDiary, SCD women had 1.85× higher acute SCD pain rate in the third trimester and puerperium compared to 6 to 9 months after childbirth.

In the third trimester and puerperium, self-reported eDiary acute SCD pain rate at home was 5.29x higher than pain requiring hospitalization.

Visual Abstract

Pregnant women with sickle cell disease (SCD) are at higher risk of SCD-related morbidity and mortality than after pregnancy. Existing data from health care use suggest increased acute vaso-occlusive pain events during pregnancy, particularly in the third trimester and puerperium (6 weeks after childbirth). Many acute vaso-occlusive pain events are managed at home and may not capture the full scope of pregnancy-related morbidity. To date, to our knowledge, no studies have examined daily self-reported acute vaso-occlusive pain events during pregnancy and after pregnancy to assess their occurrence at home. Based on self-report using an electronic diary (eDiary) mobile application, we tested the primary hypothesis that self-reported acute SCD pain events during pregnancy (third trimester to puerperium) are greater than after pregnancy (beginning of 6, to end of 9 months, after childbirth).In a tertiary care hospital in Ghana, we approached 42 pregnant women with SCD at ≤16 weeks gestation to participate in the prospective study; 40 of 42 (95.2%) pregnant women with SCD agreed to participate; only 33 participants completed 71.5% of expected eDiary mobile application entries during and after pregnancy. The eDiary data revealed a 1.85-fold higher self-reported acute SCD pain incidence rate during pregnancy than after pregnancy (0.74 vs 0.40 events per person-month; P < .001). Based on the eDiary mobile application, we demonstrated a higher rate of self-reported acute SCD pain during pregnancy than after pregnancy. Preconception counseling for women with SCD should address the expected increase above their baseline in acute vaso-occlusive pain events, particularly in the third trimester and puerperium.

Introduction

In women with sickle cell disease (SCD), acute vaso-occlusive pain events are the most frequent reasons for admission during pregnancy, often preceding life-threatening acute chest syndrome (ACS),1-3 and pulmonary thromboembolism. Pregnant women with SCD have an intrinsic altered physiology associated with pregnancy, including an increased metabolic demand, a hypercoagulable state, and leukocytosis (predominantly neutrophils).4 These processes predispose pregnant women with SCD to an increased risk of acute vaso-occlusive events (acute pain and ACS) and pulmonary thromboembolism, particularly in the third trimester and puerperium (6 weeks after childbirth).5

Despite the clinical impression that acute vaso-occlusive pain incidence rates in women with SCD are higher during pregnancy,5 few studies directly compare the incidence rate of acute vaso-occlusive pain in the home environment, in which most acute SCD pain events are managed,6 with the incidence rate of acute vaso-occlusive pain that requires hospitalization. At the multidisciplinary SCD-obstetrics clinic in Korle Bu, we educate and counsel pregnant women with SCD about the increased risk of pregnancy outcomes (including acute vaso-occlusive pain events), especially in the third trimester, and the need to report to the emergency department early. Opioids are the recommended medicines for the management of moderate to severe acute SCD pain during hospitalizations.7 Opioid usage requires good monitoring to prevent opioid toxicity and serious complications related to acute vaso-occlusive pain events such as ACS, multiorgan failure, and sudden death.8 In Ghana, >95% of disease conditions are covered by the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS).9 However, some services (including services required during hospitalizations and medicines not on the NHIS medicines list, such as opioids) are paid out-of-pocket. Financial constraints and lack of access to the NHIS of pregnant women with SCD may lead to the home management of acute SCD pain events; hence, acute pain incidence rates for hospitalizations are likely to be underreported. The pain experience of pregnant women with SCD needs to be defined because individuals with a high pain burden are more likely to experience functional disability and higher somatic burden, depression, anxiety, chronic fetal hypoxia, intrauterine growth restriction, and fetal demise.4,10,11

Pain is the primary outcome of interest for most SCD clinical trials. Pain experience is primarily subjective; hence, there is a need to integrate validated patient interactive tools for pain assessment. Ultimately, the gold standard for pain assessment is patient self-report. To assess pain as an end point in SCD clinical trials, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)/American Society of Hematology (ASH) recommends using patient-reported outcomes and non–patient-reported outcomes measures such as health care use.12 The FDA/ASH suggest using electronic diaries (eDiaries) as a reasonable option to assess pain managed at home.12 One validated tool that has been used extensively in the nonpregnant SCD population is the Sickle Cell Mobile App to Record Symptoms via Technology (SMART) tool.13-16 Previously, we demonstrated a sixfold reduction in the pain incidence rate postpartum compared with during pregnancy based on hospitalization records.5 In this prospective cohort study, based on self-report using SMART (an electronic diary [eDiary] mobile application), we tested the primary hypothesis that self-reported acute SCD pain events during pregnancy (third trimester and puerperium) are greater than after pregnancy (6-9 months after childbirth). We tested the secondary hypothesis that self-reported acute SCD pain events during pregnancy (third trimester and puerperium) are greater than acute SCD pain events requiring hospitalization during the same period.

Methods

Study design and setting

The study sites comprised the Obstetrics Department, Korle Bu Teaching Hospital; and the Ghana Institute of Clinical Genetics, Ghana’s largest adolescent and adult SCD clinic. The primary hematologist reviewed the study participants at the obstetrics clinic during pregnancy and continued their care at the adult SCD clinic after pregnancy. The primary outcome measure was the acute vaso-occlusive (SCD) pain incidence rate.

Study population

In Ghana, ∼99% of newborns delivered with SCD annually have hemoglobin SS (HbSS) and HbSC.17 Our study population included pregnant women with SCD (HbSS and HbSC, aged 18-45 years) who received their primary SCD care at the adult SCD clinic (Ghana Institute of Clinical Genetics) and presented for obstetric care at Korle Bu Teaching Hospital.

Study intervals

We recruited participants from the multidisciplinary SCD-obstetrics clinic at ≤16 weeks gestation and managed participants using standardized protocols.18 As standard care, stable pregnant women with SCD are followed up biweekly at the outpatient clinic until 34 weeks gestation and weekly until delivery.18 Women with SCD with obstetric complications are seen more frequently at the outpatient clinic as required until delivery.18 During the puerperium, the new mothers and babies are reviewed at the obstetrics clinic at 2 weeks and 6 weeks after childbirth as standard postnatal care.19 As standard care, all women with SCD are referred to the adult sickle cell clinic after puerperium to continue routine care every 3 to 6 months if stable. Active intervention with the eDiary mobile application commenced at 27 weeks gestation. The third trimester and puerperium represent the most significant risk for acute vaso-occlusive pain events in women with SCD.5 We used the eDiary mobile application only during this specific pregnancy interval. We defined the pregnancy interval as the interval between the third trimester (27 weeks gestation to delivery) and the puerperium (6 weeks after childbirth; ∼16 weeks duration). For comparison, we used the eDiary mobile application during a specific interval (after-pregnancy interval), beginning at 6 months, to the end of 9 months after childbirth (∼16 weeks duration). We chose this comparison interval because the physiological changes during pregnancy and childbirth may take >6 weeks before they return to the nonpregnant state.20,21 By 6 months after childbirth, hormonal changes in estrogen and progesterone are expected to be reset to prepregnancy levels.21 We then followed up with each participant for 1 year after childbirth.

Daily eDiary pain assessments

All participants were given a modified SMART application installed on an iPhone operating system mobile device provided by the study investigators. Participants used the SMART application daily to indicate whether they were experiencing “sickle cell pain” (defined as a self-report of acute vaso-occlusive pain that is differentiated from non-SCD pain) or “non–sickle cell pain” (defined as a self-report of pain unrelated to SCD). If sickle cell pain was selected, participants rated it on a numeric scale of 1 to 10 and indicated whether it was like their typical acute sickle cell pain event. Similar to our previous publications, if the study participant could judge whether the pain was of the type usually associated with SCD pain and self-reported such pain, the event was considered appropriate evidence of an acute SCD pain episode.2 We counted self-reports of acute SCD pain events recurring within a week as 1 event, and the initial date of the series of dates counted as the index date. Participants also documented the intervention sought for each self-reported acute SCD pain event in the eDiary mobile application. We excluded all entries during any period in which participant self-reported and was hospitalized for acute SCD pain.

Acute events leading to hospitalization

We also identified acute events using health care use records documenting hospitalization frequency and reasons for each participant’s hospitalization throughout the study period. Hospitalization included using the day hospital at the adult SCD clinic (between 2 and 7 hours in duration), emergency department visits, and admissions for >24 hours.

Acute vaso-occlusive/SCD pain events

We defined an acute vaso-occlusive/SCD pain event in pregnant women with SCD as “acute vaso-occlusive pain, which can be distinguished from labor pain based on the absence of uterine contractions, evidence of labor progression, and delivery, and required parenteral or oral opioids, and hospitalization.”2 After pregnancy, we defined an acute vaso-occlusive/SCD pain event requiring hospitalization as a self-report of acute pain related to SCD based on the chief complaint, confirmed by a health care provider, managed with parenteral or oral opioids, and requiring hospital admission. Per the recent ACTTION-APS-AAPM Pain Taxonomy (AAAPT) criteria, to fall under the diagnosis of acute pain, it must be an increased pain of new onset and have a ≥2-hour duration but not have been present for >10 days.22 We distinguished acute vaso-occlusive pain from chronic pain based on the absence of self-reports of ongoing pain present on most days over the past 6 months, either in a single location or in multiple locations,23 and the absence of self-reports or a medical diagnosis of chronic pain before pregnancy. We considered acute vaso-occlusive pain events identified through hospitalization records as uncomplicated if they were not associated with ACS, multiorgan failure, or death.8 We counted acute vaso-occlusive pain events once; thus, we counted only the hospitalization event if the participant had an acute vaso-occlusive pain event at home and was also admitted to the hospital for the acute vaso-occlusive pain event. We counted hospitalizations for acute SCD pain events recurring within a week as 1 event, and the initial date of the series of dates counted as the index date.

ACS

Based on the poorly defined definition of ACS in low-to-middle income settings and the variability of the ACS definition in high-resource settings, we validated an ACS definition in pregnant women with SCD through an adjudication process that included hematologists, obstetricians, and a research panel with a minimum of 5 individuals reviewing the symptoms and objective data.2,4 We defined ACS as abnormal findings on lung examination and the presence of at least 2 of the following criteria: temperature >38.0°C; an increased respiratory rate greater than the 90th percentile for age, positive chest pain, or pulmonary auscultatory findings; increased oxygen requirement (saturation of peripheral oxygen drop by ≥3% from a documented steady-state value on room air); and a new radiodensity on chest roentgenogram.2 A diagnosis of pneumonia was considered an ACS episode.2

Symptomatic or acute anemia

Symptomatic or acute anemia was defined as a drop in Hb by ≥2.0 g/dL below the baseline (Hb value at the time of enrollment ≤16 weeks of gestation or steady state value) or Hb of <5.0 g/dL with symptoms of anemia.24

Participant retention and compensation

The eDiary mobile application was designed to be user friendly (easy to understand and takes ∼5 minutes to complete). We allowed participants a 24-hour window to complete eDiary mobile application entries. We sent frequent reminders via phone calls, encouraging the participants to use the eDiary mobile application. We also inspected data entries in the eDiary mobile application for each participant at each clinic visit. Participants received GHS 5.00 ($0.42) compensation daily for each completed eDiary mobile application entry, with a maximum of GHS 900.00 ($75.80) at the end of the study.

Data analysis

We reported continuous variables as median and interquartile range (IQR); categorical variables and prevalence estimates as counts and percentages. We categorized acute pain as SCD pain or non-SCD pain. Adherence to the study was based on the percentage of days with eDiary mobile application entries. We reported acute SCD pain incidence rates as events per person-month. Group comparisons used χ2 or Fisher exact tests for counts, and the Mann-Whitney U test for medians. We used negative binomial regression to account for overdispersion in counts and compare the acute SCD pain incidence rates between the pregnancy and after-pregnancy intervals. We defined statistical significance as P < .05.

The study was approved by the ethical and protocol review board of the College of Health Sciences, University of Ghana (CHS-Et/M.1–4.5/2019-2020).

Results

Baseline characteristics

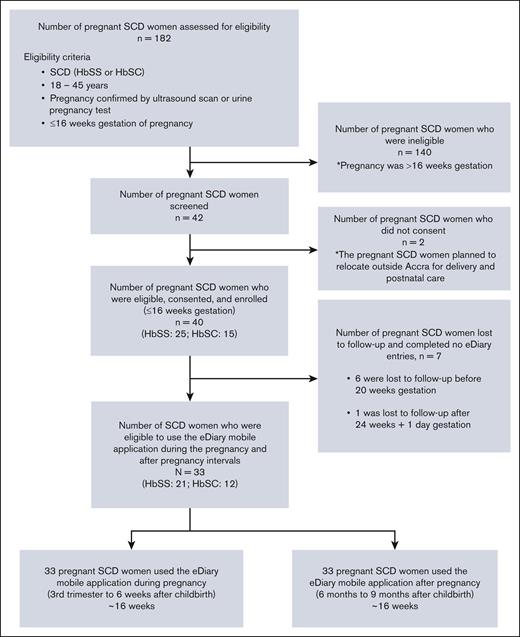

The first and last participants were enrolled on 24 February 2020 and 14 March 2022, respectively. Among 42 participants screened for eligibility, 40 (95.2%) pregnant women with SCD at gestational age ≤16 weeks consented to participate in the trial. After enrollment, 7 of 40 (17.5%) participants were lost to follow-up and completed no eDiary mobile application entries. A total of 33 of 44 (82.5%; HbSS: 21/33 [63.6%] and HbSC: 12/33 [36.4%]) completed the eDiary mobile application during the pregnancy interval (third trimester to puerperium) and the after-pregnancy interval (6-9 months after childbirth; Figure 1). The 33 participants had a median age of 31.0 years (IQR, 27.0-33.0), a median Hb of 8.6 g/dL (IQR, 6.8-9.8), and a median body mass index of 23.3 kg/m2 (IQR, 20.6-26.8). The median gestational age at enrollment was 12.7 weeks (IQR, 10.0-14.7). The combined median total study follow-up time for the 2 key intervals was 231.0 days (IQR, 203.0-252.0), with a median study follow-up time of 119.0 days (IQR, 91.0-140.0) during the pregnancy interval and 112.0 days for each participant during the after-pregnancy interval. Table 1 summarizes all study participants’ demographic, clinical, and laboratory parameters. None of the women were on any disease-modifying therapy or chronic blood transfusion before pregnancy or during the study period.

Flowchart showing the selection criteria used in a prospective cohort study of eDiary acute pain assessments in women with SCD during and after pregnancy.

Flowchart showing the selection criteria used in a prospective cohort study of eDiary acute pain assessments in women with SCD during and after pregnancy.

eDiary mobile application reports of acute non-SCD pain and acute SCD pain events

Participants self-reported acute pain (SCD and non-SCD) on 456 of 5476 (8.3%) days that they used the eDiary mobile application during the study period. There were 143 self-reported acute SCD pain events, considering exclusion rules. These represent distinct acute SCD pain events that did not involve hospitalization. Of 143 events, 98 (68.5%) occurred during the pregnancy interval, and 45 (31.5%) occurred during the after-pregnancy interval. During the pregnancy interval, all participants reported at least 1 acute SCD pain event. During the after-pregnancy interval, 25 of 33 (75.8%) reported at least 1 event. The average acute SCD pain intensity self-reported during the pregnancy interval (3.9) was higher than the after-pregnancy interval (3.3), P = .002. The pain incidence rate per person-month during the pregnancy interval was 0.74 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.61-0.90) events per person-month compared with 0.40 (95% CI, 0.30-0.53) events per person-month during the after-pregnancy interval (P < .001; Table 2). There was no significant difference in the pain incidence rate by age (P = .826) during the pregnancy interval.

Hospitalization for acute vaso-occlusive pain events

Hospitalization for acute SCD pain was much more frequent during the pregnancy interval. There were 17 admissions during the pregnancy interval and 2 during the after-pregnancy interval. During the pregnancy interval, 14 of 33 (42.4%) participants were hospitalized at least once for acute SCD pain compared with 2 of 33 (6.1%) during the after-pregnancy interval (P < .001). The median duration of hospitalization for acute SCD pain during the pregnancy interval and the after-pregnancy interval was 7.0 days vs 1.5 days, respectively (P = .019). The pain incidence rate of hospitalization per person-month during the pregnancy interval was 0.14 (95% CI, 0.08-0.22) events per person-month compared with 0.02 (95% CI, 0.00-0.06) events per person-month during the after-pregnancy interval (P < .001; Table 2).

Acute vaso-occlusive pain events at home with the eDiary mobile application vs hospitalization

During the pregnancy interval, there was a significant difference in the acute SCD pain incidence rate using the eDiary mobile application (0.74 events per person-month; 95% CI, 0.61-0.90) compared with the acute SCD pain requiring hospitalization (0.14 events per person-month; 95% CI, 0.08-0.22; P < .001; Table 2). After pregnancy, there was also a significant difference in the acute SCD pain incidence rate using the eDiary mobile application (0.40 events per person-month; 95% CI, 0.30-0.53) compared with the acute SCD pain requiring hospitalization (0.02 events per person-month; 95% CI, 0.00-0.06; P < .001; Table 2).

Adherence to the use of the eDiary mobile application

The average proportion of eDiary mobile application entries completed during the pregnancy and after-pregnancy intervals was 65.5% (78/119 days; range, 62-89) and 78.6% (88/112 days; range, 54-98), respectively. Although adherence, albeit high, was lower during the pregnancy interval, the difference was not significant (P = .083).

Other SCD-related complications

Two participants were hospitalized for an average of 6.0 days during the third trimester with a clinical diagnosis of ACS. No participant had ACS after pregnancy. The diagnosis of ACS was based on our validated adjudication criteria for ACS.2,3,5,25 None of the 2 participants had a chest radiograph done.

Few participants, 5 of 33 (15.2%; all HbSS), had simple red cell transfusions for symptomatic anemia (decline in their Hb by ≥2.0 g/dL compared with baseline) during the pregnancy interval. No participant had a simple red cell transfusion during the after-pregnancy interval.

Discussion

Acute vaso-occlusive (SCD) pain events are a major complication of pregnancy in SCD and the primary risk factor for ACS during pregnancy, the primary cause of death in pregnant women. To our knowledge, we are the first to report a prospective cohort study using an eDiary mobile application in pregnant women with SCD, describing the acute SCD pain incidence rate during and after pregnancy in the same women. Comparing the pregnancy interval (third trimester to puerperium) with the after-pregnancy interval (6-9 months after childbirth), using an eDiary mobile application, we identified a 1.85-fold higher self-reported acute SCD pain incidence rate during the pregnancy interval. We also demonstrated that during the pregnancy interval (third trimester to puerperium), self-reports of acute SCD pain using an eDiary mobile application had a 5.29-fold higher acute SCD pain incidence rate compared with acute SCD pain requiring hospitalization.

Previous studies in both high- and low-resource settings have reported a prevalence of acute vaso-occlusive pain events during pregnancy as high as 75%.2 Limited studies have reported increased hospitalization for acute vaso-occlusive pain events during pregnancy but did not directly compared pregnancy with prepregnancy.26-28 One meeting abstract with a small sample size and a retrospective study design reported that a history of painful events before pregnancy was associated with having at least 1 painful event during pregnancy.29 Despite the clinical impression that acute vaso-occlusive pain incidence rates in women with SCD are higher during pregnancy,5 few studies directly compare the incidence rate of acute vaso-occlusive pain in the home environment, in which most acute SCD pain events are managed, with the incidence rate of acute vaso-occlusive pain that requires hospitalization.6 Previously, we demonstrated a sixfold reduction in the pain incidence rate postpartum compared with pregnancy.5 This comparison was, however, based on hospitalization records and recall, and not the home experience. In this study, using an eDiary mobile application, we also identified a 5.29-fold higher acute SCD pain incidence rate at home compared with acute SCD pain requiring hospitalization during pregnancy (third trimester to puerperium) and a 20-fold higher acute SCD pain incidence rate at home compared with acute SCD pain requiring hospitalization after pregnancy (6-9 months after childbirth). These findings corroborate Smith et al’s6 findings in the nonpregnant SCD population that reported that most acute vaso-occlusive pain events occur in the home environment.

Current FDA-approved disease-modifying treatments for individuals with SCD, including hydroxyurea, L-glutamine, and crizanlizumab, are not licensed for use in pregnancy and, therefore, not recommended.30,31 Active research is being done to address whether red cell transfusion reduces acute vaso-occlusive pain events in pregnant women with SCD, although red cell transfusion is considered low-risk by the ASH.31-34 Globally, there are challenges with access to, and use of, red cell transfusion, especially in low-resource settings.35 With appropriate regulatory oversight, there is an urgent need to include pregnant women with SCD in clinical trials that test the efficacy and safety of new and alternative therapies for pain management at home and during hospitalizations.

The main strengths of our study design are the entry criteria that included enrollment at ≤16 weeks gestation and our ability to address acute vaso-occlusive pain events after pregnancy using an eDiary mobile application when the new mother is unlikely to leave her breastfeeding newborn to be evaluated in the hospital. We deliberately structured the period between recruitment and the start of the intervention to build rapport with participants and establish trust. This approach was part of our retention strategy to ensure sustained engagement throughout the study, especially during the critical later stages of pregnancy when acute vaso-occlusive pain events were likely to increase. The home monitoring of acute vaso-occlusive pain events using mobile technology is required to describe the full spectrum of acute vaso-occlusive pain events because most acute vaso-occlusive pain events occur and are managed at home.

Despite attrition and nonadherence being common limitations of remote monitoring tools,15,36 our study had low attrition and high adherence rates. The eDiary mobile application attrition rate was 0%, and the eDiary mobile application adherence rate over ∼33 weeks (∼16-17 weeks per interval) was 71.5%. We attribute the low attrition and high adherence rates to the engagement and retention strategies used by the research personnel at the onset of the study. Our research team has consistently demonstrated low attrition (<5%) and high adherence rates (>95%) in our multidisciplinary SCD-obstetric clinic.18,25,37 Another key factor is the compensation provided for daily use of the eDiary mobile application. Furthermore, the eDiary mobile application was designed to be user-friendly (easy to understand, and it takes ∼5 minutes to complete). It allows participants a 24-hour window to complete entries and frequently reminds them via phone calls, encouraging them to use the application. We also inspected data entries in the eDiary mobile application for each participant at each clinic visit.

As anticipated, our study has several limitations. A potential limitation was participant fatigue associated with using the eDiary mobile application. Many studies using mobile applications have reported evidence of user fatigue,15,38-40 and an average retention rate of <5% after 30 days.36 However, in our study, the average adherence rate to using the eDiary was 65.1% (range, 62-89) during the pregnancy interval and 78.6% (range, 54-98) during the after-pregnancy interval, which was comparable with the adherence rate of 85% (the median number of 158 diaries completed) reported by Smith et al6 in the PiSCES (Pain in Sickle Cell Epidemiology Study) study. As a result, our study’s eDiary mobile application pain incidence rates are conservative estimates because of high, but far from complete, adherence. Another limitation was that we did not capture detailed qualitative descriptions of acute vaso-occlusive pain. Individuals with SCD describe SCD pain using both nociceptive and neuropathic descriptors, suggesting that SCD pain has a multifaceted etiology.41 Capturing qualitative descriptions of acute vaso-occlusive pain may have distinguished nociceptive pain from neuropathic pain and subsequently helped in the recommendation of other analgesics to be used during pregnancy. Based on the rate of pregnancy in our population and the entry criterion of being ≤16 weeks pregnant, we estimate that we would have to enroll >900 nonpregnant women of childbearing age to achieve an enrollment of 35 participants who met our entry criterion. Because of restraints in budget and personnel, we could not prospectively enroll women with SCD before pregnancy and establish the baseline pain rate with the mobile application before pregnancy. We also could not collect data to establish the pain rate after the puerperium up to 6 months after childbirth with the mobile application, because of restraints in our budget, and the evidence of established user fatigue with the usage of the mobile application for longer periods. As stated earlier, many studies using mobile applications have reported evidence of user fatigue,15,38-40 and an average retention rate of <5% after 30 days.36 A perceived limitation of our study is the relatively small sample size (n = 33). However, we had a P value of < .001 for our primary and secondary hypotheses; hence, the likelihood of a false positive is low, even if we doubled the sample size. Our study was conducted in a single center and may not be representative of all pregnant women with SCD. However, the higher pain event rate at home when compared with hospitalization is exactly what other studies have demonstrated in SCD6,42; and the results are consistent with our clinical experience managing ∼1500 pregnant women with SCD at our tertiary care center since the start of our multidisciplinary SCD-obstetrics clinic in 2015.

In summary, our novel observational study using an eDiary mobile application demonstrated that pregnant women with SCD have a 1.85-fold higher self-reported acute SCD pain incidence rate during the pregnancy interval compared with during the after-pregnancy interval. We also demonstrated that self-reports of acute SCD pain during pregnancy and puerperium using an eDiary mobile application had a 5.29-fold higher pain incidence rate compared with acute SCD pain requiring hospitalization during the same period. Hospitalization for acute SCD pain during pregnancy results in a significantly longer stay compared with after pregnancy, and the resolution of acute SCD pain is also extended. Our results indicate that counseling for women with SCD should address the expected increase in acute vaso-occlusive pain events during pregnancy (both at home and requiring hospitalization), especially in the third trimester and puerperium. With appropriate regulatory oversight, further studies need to focus on the management of acute SCD pain at home and during hospitalizations.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of Jude Jonassaint (University of Pittsburgh) and Charles Jonassaint (University of Pittsburgh) in developing the Sickle cell Mobile Application to Record Symptoms via Technology application for the electronic diary mobile application used for the pain assessment in women with sickle cell disease during pregnancy and after pregnancy.

This study was supported by funds from the American Society of Hematology Global Research Awards (2019-2023), a generous donation from the David and Mary Phillips Foundation, and a generous donation from the Ardoin Foundation Supporting Sickle Cell Research and Education (E.V.A.).

Authorship

Contribution: E.V.A., S.A.O., C.R.J., J.J., and M.R.D. designed the study; E.V.A., W.K.G., J.B.A.-N., and E.A.M. collected the data; E.V.A., W.K.G., J.B.A.-N., A.S.-D., T.B., S.A.O., and E.O. adjudicated the case files; E.V.A., J.B.A.-N., M.R.D., and M.R. performed the analyses; E.V.A., W.K.G., J.B.A.-N., S.A.O., M.R.D., and M.R. interpreted the results; E.V.A. confirms that she had full access to all data in this study and was finally responsible for the decision to submit it for publication; and all authors participated in writing the article and reviewed and approved the manuscript before submission.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: E.V.A. received research funding from the American Society of Hematology (ASH) Global Research Award (2019-2023); participated in ASH Clinical Research Training Institute (CRTI) North America (2017/2018); and received a generous donation from David and Mary Phillips Foundation and the Aaron Ardoin Foundation Supporting Sickle Cell Research and Education. M.R.D. is the chair of the steering committee for a Novartis-funded clinical trial in men with sickle cell disease receiving crizanlizumab for secondary priapism prevention. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Eugenia V. Asare, Department of Haematology, Korle Bu Teaching Hospital, P.O. Box KB77, Korle Bu, Accra, Ghana; email: eugquart@gmail.com.

References

Author notes

Original data are available on request from the corresponding author, Eugenia V. Asare (eugquart@gmail.com).