Key Points

ML-NLP can be an effective method for identifying venous thromboembolism in free-text reports.

The highest performing models use vectorization rather than bag-of-words and deep-learning techniques, like convolutional neural networks.

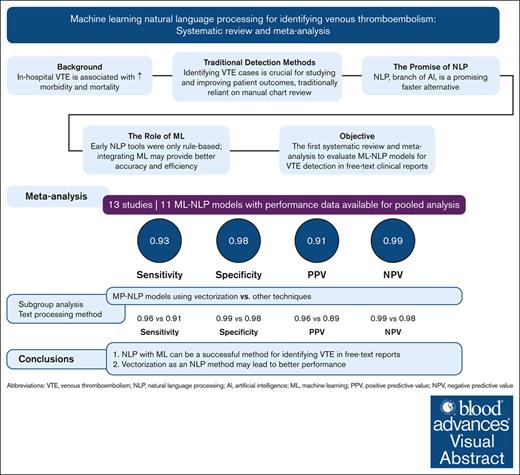

Visual Abstract

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a leading cause of preventable in-hospital mortality. Monitoring VTE cases is limited by the challenges of manual medical record review and diagnosis code interpretation. Natural language processing (NLP) can automate the process. Rule-based NLP methods are effective but time consuming. Machine learning (ML)-NLP methods present a promising solution. We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies published before May 2023 that use ML-NLP to identify VTE diagnoses in the electronic health records. Four reviewers screened all manuscripts, excluding studies that only used a rule-based method. A meta-analysis evaluated the pooled performance of each study’s best performing model that evaluated for pulmonary embolism and/or deep vein thrombosis. Pooled sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) with confidence interval (CI) were calculated by DerSimonian and Laird method using a random-effects model. Study quality was assessed using an adapted TRIPOD (Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis Or Diagnosis) tool. Thirteen studies were included in the systematic review and 8 had data available for meta-analysis. Pooled sensitivity was 0.931 (95% CI, 0.881-0.962), specificity 0.984 (95% CI, 0.967-0.992), PPV 0.910 (95% CI, 0.865-0.941) and NPV 0.985 (95% CI, 0.977-0.990). All studies met at least 13 of the 21 NLP-modified TRIPOD items, demonstrating fair quality. The highest performing models used vectorization rather than bag-of-words and deep-learning techniques such as convolutional neural networks. There was significant heterogeneity in the studies, and only 4 validated their model on an external data set. Further standardization of ML studies can help progress this novel technology toward real-world implementation.

Introduction

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), which includes pulmonary embolism (PE) and deep venous thromboembolism (DVT), is an important cause of adverse outcomes in hospitalized patients including mortality and readmission.1 Apart from mortality from acute PE, survivors continue to be at risk for other complications, including VTE recurrence, posttraumatic stress, chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension, and post-thrombotic syndrome.2 Given the significant morbidity, mortality, and associated cost, inpatient VTE has become a key indicator of quality and safety in clinical practice.3 The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality identified appropriate thromboprophylaxis as “the number 1 patient safety practice”4 and hospital quality measures include VTE documentation and outcomes.5

The first step in reducing in-hospital VTE events is to understand when and how frequently these events occur.3 Historically, manual medical record review was considered the gold standard for identifying cases, but this method is resource intensive and challenging to scale. Diagnosis codes are another common strategy but have variable accuracy.6,7 It can also be difficult to determine from diagnosis codes whether the PE is an acute event during the index hospitalization or if the code reflects a historical event. With the wide implementation of electronic health records (EHRs), we now have a rich source of inpatient data available for analysis. However, a significant portion of the information related to VTE events exists in unstructured free text, such as clinical notes and radiology reports. Natural language processing (NLP) has therefore emerged as a promising solution for extracting this data.

NLP is a branch of artificial intelligence that aims to give computers the ability to understand written and spoken language.8 Successful application of NLP would allow for rapid and accurate detection of specified findings, and generation of curated data sets valuable for both research and quality improvement.9 Initial attempts to use NLP for identifying VTE events focused on rule-based techniques such as PEFinder and MedLEE (Medical Language Extraction and Encoding System).10,11 These strategies use the semantic and syntactical characteristics of written language to develop a set of rules for parsing narrative documents. Although they are effective, a clinical expert needs to devote significant time upfront to define the rules, and the rules are inherently limited to the specific clinical scenario and language they serve.12

NLP has become more sophisticated and automated over time by integrating machine learning (ML) techniques. This systematic review and meta-analysis evaluates the current state of NLP that uses ML to review free-text reports for VTE diagnosis. We compare the different ML techniques used and report on their pooled performance. We also propose a new tool for assessing the quality of NLP studies and use that tool to evaluate each study reviewed.

Methods

This systematic review was registered with PROSPERO (International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews; registration no. 351660) and was conducted in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions and reporting requirements outlined by PRISMA-DTA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Diagnostic Test Accuracy) checklist (included in the supplemental Materials).

Search strategy

A systematic literature search strategy was executed on 20 April 2021 and updated on 12 May 2023 in the databases of MEDLINE, EMBASE, PubMed, and Web of Science. A combination of controlled Medical Subject Headings vocabulary and keyword terms was used. The search strategy contained the following terms: “Artificial Intelligence” or “Machine Learning” or “Natural Language Processing” combined with terms using and “Venous Thromboembolism” or “Deep Vein Thrombosis” or “Venous Thrombosis” or “Pulmonary Embolism” or “Thrombosis.” English was added as a language limit. The detailed search strategy is included in the supplemental Materials.

Manual screening

Two reviewers (among B.L., P.C., H.K., or R.P.) independently screened all titles and abstracts in the Covidence online platform. Disagreements were reconciled by a third reviewer. After this screening process, each reviewer reviewed the full-text article for eligibility. Only studies using NLP with an ML method to identify VTE diagnoses in narrative text were included. We included studies that developed novel methods as well as those that used an out-of-the-box algorithm to retrospectively analyze a data set. We excluded studies that were only available in abstract form, studies that used rule-based algorithms without additional ML techniques, studies that did not declare using an ML method, and non-English manuscripts.

Data extraction

We extracted information on the country, hospital setting, number of participating sites, data set size, NLP technique, ML method, training approach, validation methods, reference standard, language of the free-text data, performance metrics, comparators, availability of the data set, and availability of the source code.

Meta-analysis

We performed a meta-analysis to determine the pooled sensitivity and specificity of the studies. We also compared the performance of studies that used word vectorization vs other methods, such as bag of words. Data analysis was performed using Comprehensive Meta-analysis (version 3.0.; Eaglewood, NJ). Pooled sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) were calculated by the DerSimonian and Laird method using a random-effects model. If a manuscript evaluated multiple ML techniques, we used the performance metrics of the best performing algorithm. If a manuscript evaluated their model on multiple data sets, we included all analyses that reported performance measures. Models that classified presence vs absence of DVT and/or PE were included in the meta-analysis. If sensitivity and specificity were not directly reported in the manuscript, they were calculated using available numbers.

Quality assessment

We adapted the TRIPOD (Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis Or Diagnosis) tool13 to be more specific to NLP studies (supplemental Table 1), and used the modified tool to assess the quality of each study. The modifications were based on previously published systematic reviews of NLP studies.14,15

Results

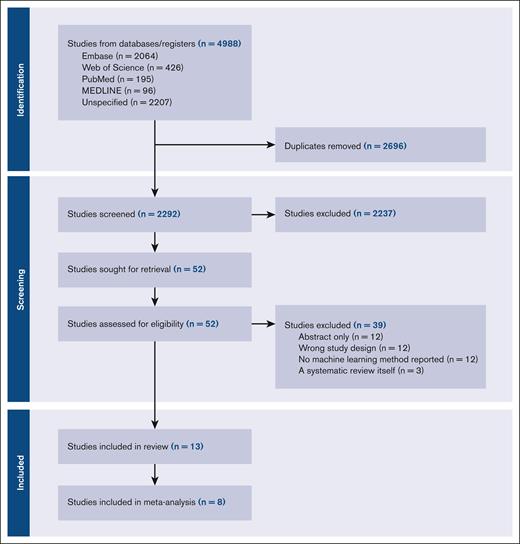

The PRISMA diagram is presented in Figure 1. The literature search yielded 4988 records and 2292 were screened after removal of 2696 duplicates. A total of 52 studies were further assessed for eligibility based on the full text and 39 were ultimately excluded; 12 evaluated a rule-based algorithm with no ML technique specified, 12 were only available in abstract form and had not been published in a peer-reviewed journal, and the remaining manuscripts were excluded due to study design, for example using an NLP method to detect VTE risk factors rather than the diagnosis of VTE.

General study and data set characteristics

A total of 13 studies were included in the systematic review16-28 (Table 1). All studies were conducted in a high-income country, with most located in the United States (69.2%). Eleven studies evaluated the free text of radiology reports; 2 studies reviewed all clinical narrative text in the EHR.19,26 The majority (76.9%) used text in the English language, while the remaining 3 extracted text in Russian, French, and German. All studies used at least 1 clinician's review of the report as their reference standard.

Data set size, which specifies the number of reports included, ranged from 572 to 117 915 reports. Only 1 study included reports from multiple hospitals to train their models. All studies used retrospective data from their home institution, and no studies specified whether the data or code would be made publicly available.

Eleven studies developed their own model; Wendelboe et al28 validated a previously created tool, and Shah et al26 used a proprietary NLP tool. All models evaluated for the presence of PE and/or DVT while 2 studies (Rochefort et al22 and Selby et al23) evaluated for the presence of DVT and PE separately. Five studies developed additional classifiers: Pham et al21 evaluated for the presence of incidentalomas, Banerjee et al17 evaluated PE chronicity (acute vs chronic), and Banerjee et al,16 Chen et al,18 and Yu et al25 evaluated PE chronicity as well as PE location (central vs subsegmental). These additional classifiers tended to have lower performance metrics than models that evaluated for presence of VTE (supplemental Table 2).

Text processing method

Six studies (Danilov et al,19 Dantes et al,20 Fiszman et al,27 Pham et al,21 Shah et al,26 and Yu et al25) used a rule-based NLP method for initial text preprocessing. A rule-based approach uses a set of human-created rules to classify words and phrases in the text. Two studies (Rochefort et al22 and Selby et al23) used a bag-of-words approach and 2 studies (Banerjee et al17 and Chen et al18) used Global Vectors for Word Representation (GloVe), an unsupervised learning algorithm for obtaining vector representations for words.29 A bag-of-words model counts occurrences of words without preserving context, whereas GloVe considers neighboring text. Banerjee et al16 and Weikert et al24 used a combination of rule-based methods and vectorization.

ML technique, training, and validation

ML techniques ranged from more traditional methods, such as logistic regression (LR) and random forest (RF), to more modern deep-learning techniques, such as convolutional neural networks (CNN). All studies described a training approach where the training and testing data did not overlap. Very few studies described their hyperparameter tuning approach; 3 reported used a k-fold cross validation approach16,22,24 and 2 described using a calibration set.17,18

Four studies compared multiple ML approaches.17,21,24,25 Even simpler ML techniques such as support vector machine (SVM) and LR tended to perform well; not all reported an area under the curve (AUC), but all reported an F1 score >0.90 (supplemental Table 3). Five of the studies also evaluated a rule-based-only method’s performance on their test set to compare performance to their ML model16-20; these tended to perform similarly to the ML models except in the Banerjee et al16 group, which showed statistically significant improved performance of their Intelligent Word Embedding approach compared with the rule-based PEFinder, even when evaluated on the original data set that was used to train PEFinder.

Weikert et al24 did not compare their model to a rule-based method but did evaluate how many reports had the exact phrase “no pulmonary embolism” to get a sense for how a rule-based algorithm might perform. Their analysis found that 44.8% of radiology reports from the year 2016, 66.8% of radiology reports from 2017, and 68.5% of radiology reports from 2018 contained the exact phrase. They also calculated the number of impressions needed to achieve accuracy in their model; they started training with 50 impressions, incrementally increasing by 60 impressions per training cycle and measuring performance on a 900-impression test data set at the end of each training cycle. They repeated the process 100 times to account for the different impressions included in each cycle. Although 2801 reports were ultimately used for training, they found that an accuracy of over 93% was reached at training subset sizes of 170 for their SVM model, 470 for their RF model, and 470 for their CNN model.

Three studies (Banerjee et al,16 Banerjee et al,17 and Chen et al18) additionally validated their model on at least 1 external data set. Performance tended to decrease on these external data sets (Table 1). Wendelboe et al28 validated the IDEAL-X (Information and Data Extraction using Adaptive Online Learning) tool, which had been developed at Emory University20 (Atlanta, GA) on a data set that included reports from 2 external hospitals and found that performance was similar. Additional error analysis showed that many errors were from V/Q scan reports, which the original model had not been trained on. No study validated their model on different types of free-text data (eg, radiology reports vs clinical notes) than the model was originally trained on.

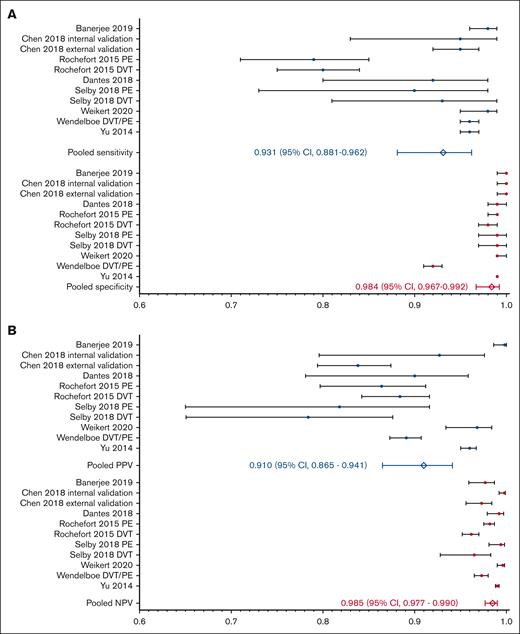

Performance assessment and meta-analysis

There was heterogeneity in how studies reported model performance. Most studies used AUC and F1 score; when reported, AUC was >0.90. Other performance measures included precision, recall, sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV. A total of 8 studies (with 10 different models) reported sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV or had the numbers available to manually calculate them (Figure 2). The pooled sensitivity was 0.93 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.88-0.96) and the specificity was 0.98 (95% CI, 0.97-0.99). The pooled PPV was 0.91 (95% CI, 0.87-0.94) and the NPV was 0.99 (95% CI, 0.98-0.99). The pooled performance of the 4 studies that used word vectorization16-18,24 was higher than studies that used a different approach, such as bag of words: sensitivity 0.96 (95% CI, 0.94-0.98) vs 0.91 (95% CI, 0.82-0.96), specificity 0.99 (95% CI, 0.94-0.99) vs 0.98 (95% CI, 0.96-0.99), PPV 0.96 (95% CI, 0.85-0.99) vs 0.89 (95% CI, 0.82-0.93), and NPV 0.99 (95% CI, 0.97-0.99) vs 0.98 (95% CI, 0.97-0.99).

Performance assessment. (A) Pooled analysis of studies that reported sensitivity and specificity of venous thromboembolism identification by ML-based NLP. (B) Pooled analysis of studies that reported PPV and NPV of venous thromboembolism identification by ML-NLP.

Performance assessment. (A) Pooled analysis of studies that reported sensitivity and specificity of venous thromboembolism identification by ML-based NLP. (B) Pooled analysis of studies that reported PPV and NPV of venous thromboembolism identification by ML-NLP.

Quality assessment

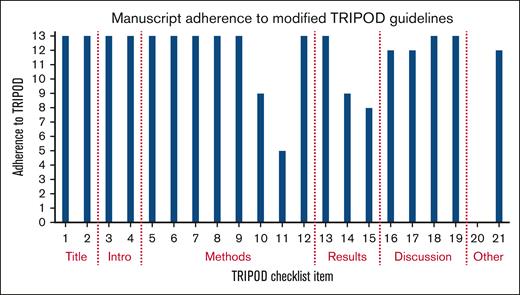

All studies met at least 13 of the 21 NLP–modified TRIPOD items, demonstrating fair-quality studies (Figure 3). None of the studies addressed the potential sharing of their code or data set, 4 studies provided incomplete performance metrics, and 1 study did not specify the ML technique their tool used.

Study adherence to TRIPOD guidelines modified for studies assessing NLP. Checklist items correspond to supplemental Table 1, the modified TRIPOD checklist for NLP studies.

Study adherence to TRIPOD guidelines modified for studies assessing NLP. Checklist items correspond to supplemental Table 1, the modified TRIPOD checklist for NLP studies.

Discussion

NLP can unlock the trove of free-text information buried in EHRs, transforming narrative text into valuable data and insights.31 Historical methods relied on rule-based algorithms, which are resource intensive to build and limited by a lack of portability to other clinical settings.32 Adding an ML approach allows NLP models to be more easily trained and more widely applicable.33 This systematic review and meta-analysis of 13 studies shows that NLP with ML can be a successful method for identifying VTE in free-text reports. The overall performance was high, with a pooled sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV of >90%.

Studies that utilized vectorization as an NLP method led to better performance than other approaches, and there are out-of-the-box tools such as word-2-vec that can assist with this preprocessing.30 Many studies described better performance with structured text; for example, Fiszman et al27 showed that their tool performed better when radiology reports were preprocessed to only include the “impression” section and Shah et al26 showed that their tool performed better on extracting information that tends to be stored in standardized sentences. This suggests that studies using clinical notes, which can be more varied in length and format, may struggle to identify VTE diagnoses. However, in this review, the 2 studies19,26 that evaluated clinical notes performed similarly to the studies that evaluated radiology reports, which has important implications for transfer learning.

ML-based algorithms performed as well as or better than rule-based approaches, consistent with prior reports in the literature.32 Several studies also compared a more traditional ML approach, such as LR or SVM, to a more modern deep-learning approach such as CNN. Although deep-learning models tended to outperform simpler models, the simple ML approaches still achieved high performance scores. These traditional approaches use less computing power and require less data and may be a good first step for institutions looking to implement these types of algorithms.34

ML approaches may require less upfront time than rule-based approaches, but expert clinicians are still needed to label the initial training data set.32 All of these studies had a clinician review the training reports to determine whether or not there was a VTE diagnosis; these clinician diagnoses then acted as the source of truth for training the models. Dantes et al found that 50% of the reports had to be manually processed before the model achieved >95% sensitivity and specificity.20 Interestingly, Weikert et al found that only a small portion of their training data set was needed to achieve an accuracy of over 93%; they had an initial training set of 2801 reports but only 170 reports were needed for the SVM model to achieve >93% accuracy.24 Further studies on reducing the training set size can minimize the resources needed to develop these types of models. Newer NLP methods that use a pretrained masked language model or large language model may help with this resource barrier.35-37 These large transformer models, such as GPT-4,38 have been trained on vast amounts of data and can be fine-tuned to work on related but different tasks.39 Transformer models such as Med-PaLM and GatorTron that have been trained specifically on clinical text may be especially promising for parsing EHR data.37,40 Caution is needed when using these foundation models however, because they can encode and amplify the biases found in their training data.40

Despite fair adherence to the requirements listed in our modified TRIPOD tool, there were many areas of heterogeneity in the studies. There was significant variability in the evaluation metrics used, making it difficult to compare performance across studies. Many studies used accuracy as a measure, which can be a misleading representation of model performance when there is a small portion of true positives in the data set. Different studies used different terminology to describe their computer science approach; what some studies term a “validation” set may be a “test” set in others. Less than half of the manuscripts described their hyperparameter tuning process. Few studies validated their model on an external data set, no studies made their code publicly available, and no studies attempted to use their tool to interpret other types of free-text data. Patient-level demographic information was not regularly provided, making it difficult to assess for potential sources of bias and whether these models would generalize well to other care settings. Finally, although overall performance was high, all of these models were validated retrospectively on cleaned data sets.

Our findings highlight the following important areas for researchers to focus on: (1) standardization in how these studies are conducted and how findings are reported is needed to advance the field. Our modified TRIPOD tool offers a potential benchmark for future studies; (2) text preprocessing approaches and model development should be described in detail including model selection, hyperparameter tuning, and selection of outcome measures; (3) studies should assess their own approaches for bias and discuss what strategies were used to mitigate bias; (4) code should be shared publicly when possible and creation of common evaluation data sets can help ensure future studies are reproducible and transferrable; and, (5) there should be discussion of how the model can be applied to other clinical texts and settings, and more models need to be validated prospectively in real-world clinical settings.

NLP models trained using an ML approach can be an effective method for identifying VTE in free-text reports. The use of NLP models could be further informed by standardization in how these studies are conducted, evaluation via common benchmark data sets, and standardization in how findings are reported. The amount of information shared in each study was variable, and it is difficult to determine whether these models can be successfully implemented at other institutions. There is still significant progress to be made in the field of ML validation and implementation before the technology is incorporated into care.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA (Cooperative Agreement #DD20-2002). J.I.Z. and S.M. are supported in part through the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748. R.P. is supported in part through Conquer Cancer Foundation, Career Development Award.

Authorship

Contribution: B.D.L., A.A., N.R., K.A., and R.P. conceptualized the study; B.L., D.K., and M.M. contributed in database search; B.L., P.C., H.K., and R.P. screened the abstracts and full texts; B.L., P.C., T.C., and D.K. extracted and analyzed the data; B.L., I.S.V., J.I.Z., and R.P. conducted quality appraisal; B.L. wrote the original draft; B.L., P.C., T.C., A.A., N.R., K.A., S.M., and R.P. edited the manuscript; and B.L., P.C., J.I.Z., and R.P. revised the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: R.P. reports consultancy with Merck. Outside current work, J.I.Z. reports prior research funding from Incyte and Quercegen; consultancy for Sanofi, CSL Behring, and Calyx. Outside current work, S.M. has served as an adviser for Janssen Pharmaceuticals and is the principal owner of Daboia Consulting LLC. S.M. has a patent application pending and is developing a licensing agreement with Superbio.ai for NLP software not featured in this work. T.C. reports consultancy for Takeda, outside of current work. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Rushad Patell, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, 330 Brookline Ave, Boston, MA 02215; email: Rpatell@bidmc.harvard.edu.

References

Author notes

All data are available on request from the corresponding author, Rushad Patell (Rpatell@bidmc.harvard.edu).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.