Key Points

The risk-based letermovir use strategy is effective for CMV infection prophylaxis and allows some patients at low risk not to use letermovir.

Among patients at low risk without letermovir, most had negative or transient positive CMV DNA without clinically significant CMV infection.

Abstract

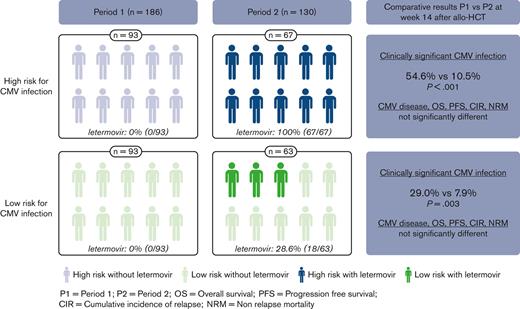

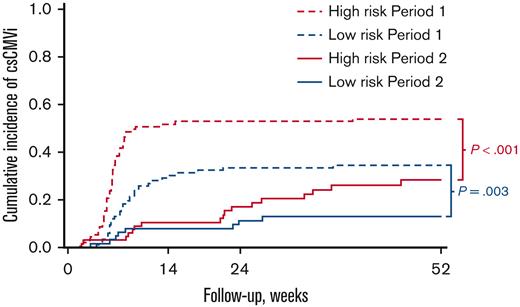

Letermovir is the first approved drug for cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection prophylaxis in adult patients who are CMV positive undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (allo-HCT). Because CMV infection risk varies from patient to patient, we evaluated whether a risk-based strategy could be effective. In this single-center study, all consecutive adult patients who were CMV positive and underwent allo-HCT between 2015 and 2021 were included. During period 1 (2015-2017), letermovir was not used, whereas during period 2 (2018-2021), letermovir was used in patients at high risk but not in patients at low risk, except in those receiving corticosteroids. In patients at high risk, the incidence of clinically significant CMV infection (csCMVi) in period 2 was lower than that in period 1 (P < .001) by week 14 (10.5% vs 51.6%) and week 24 (16.9% vs 52.7%). In patients at low risk, although only 28.6% of patients received letermovir in period 2, csCMVi incidence was also significantly lower (P = .003) by week 14 (7.9% vs 29.0%) and week 24 (11.2% vs 33.3%). Among patients at low risk who did not receive letermovir (n = 45), 23 patients (51.1%) experienced transient positive CMV DNA without csCMVi, whereas 17 patients (37.8%) experienced negative results. In both risk groups, the 2 periods were comparable for CMV disease, overall survival, progression-free survival, relapse, and nonrelapse mortality. We concluded that a risk-based strategy for letermovir use is an effective strategy which maintains the high efficacy of letermovir in patients at high risk but allows some patients at low risk to not use letermovir.

Introduction

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection, defined as detection of CMV nucleic acid in any body fluid or tissue specimen, has historically been common after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (allo-HCT), particularly in recipients who are CMV-positive, depending on the transplantation modalities and the characteristics of the donor/recipient match.1,2 CMV disease, which is the clinical expression of CMV infection, has significantly decreased with the use of a preemptive strategy based on regular monitoring of circulating CMV DNA and initiation of preemptive antiviral therapy at predefined thresholds.3,4 Recently, letermovir, a CMV DNA terminase complex inhibitor, has been approved for the prophylaxis of CMV infection and disease in adult recipients of allo-HCT who are CMV-positive, based on results of a clinical trial published by Marty et al5 in 2017. This large, randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 study showed that letermovir significantly reduced the risk of clinically significant CMV infection (csCMVi; defined as CMV disease or CMV viremia leading to preemptive treatment) by week 24 after transplantation. Because results were consistent across risk groups, letermovir was considered as a universal prophylaxis through day 100 after allo-HCT in the CMV-positive population.6 Although previous retrospective studies linked CMV infection with an increased risk of overall mortality, thus allowing viral load to be used as a surrogate clinical end point in clinical trials, when compared with that in placebo recipients, all-cause mortality through week 48 after allo-HCT was not significantly lower in letermovir recipients, especially in patients at low risk for CMV infection.7,8

In view of these conflicting results, it is quite possible that the efficiency of letermovir could be discussed in patients with low CMV infection risk.9 The recommended thresholds for initiating anti-CMV therapy in the phase 3 study were lower (>300 copies per mL for patients at low risk and >150 copies per mL for patients at high risk) than those used in practice, and we can assume that without treatment, these patients would have experienced only transient episodes of low detectable viremia without CMV disease.10 Furthermore, compared with solid transplantation in which valganciclovir prophylaxis has long been used without significant toxicity, recent studies in this area have shown that preemptive and prophylactic strategies are comparable in selected patients.11 CMV infection risk in the allo-HCT setting depends on several risk factors, as described in a number of retrospective studies.12-16 The high-risk group in the letermovir phase 3 study was defined as presenting one or more of the following defined criteria: related or unrelated donor with mismatch, haploidentical donor, use of cord blood, use of ex vivo T-cell depleted graft, and having graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).5 However, when considered separately, the predictive value of these factors is poor. Recently, we developed a simple weighted score (excluding haploidentical and second transplantations) from 0 to 20 points that evaluates, at the time of transplant, a patient’s risk of developing csCMVi (unrelated donor: +5; antithymocyte globulin: +4; CMV-negative donor: +3; mycophenolate mofetil: +3; total body irradiation: +3; and myeloablative conditioning: +2) and which classifies patients into 4 risk groups with distinct predicted rates of CMV infection.17

The objective of this study was to evaluate whether a risk-based strategy could maintain the efficacy of letermovir against csCMVi without impairing related outcomes.

Material and methods

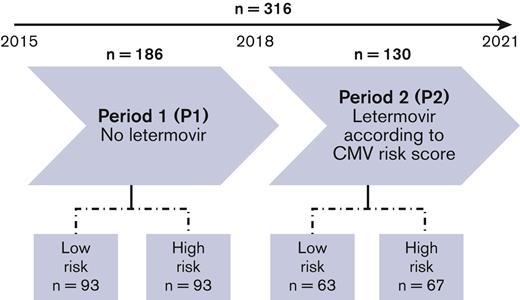

Patients

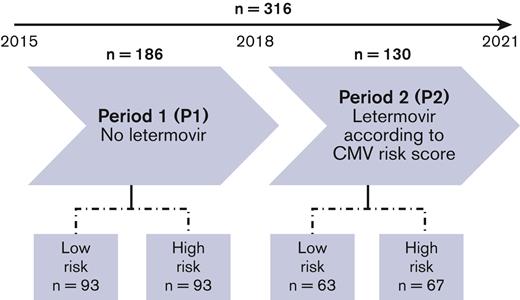

All consecutive adult patients who were CMV positive and underwent allo-HCT from 1 January 2015 to 31 July 2021 at the Lille University Hospital, France were included. Patients were divided into 2 periods based on the date of transplantation: a first period (period 1) without any use of letermovir between 1 January 2015 and 31 December 2017, and a second period (period 2) with the use of letermovir based on the risk of CMV infection between 1 January 2018 and 31 July 2021. Inside of each period, patients were identified as being low-risk (CMV risk score low [0-4 points] or intermediate-low [5-10 points]) or as high-risk for csCMVi (CMV risk score intermediate-high [11-14 points] or high [15-20 points], haploidentical transplantation and second transplantation). Prospectively collected data came from Project Manager Internet Server (ProMISe), the international database coordinated by European Society for Bone Marrow Transplantation, and on-site individual patient files were used. The follow-up was censored as of 31 December 2021. The study was led according to the Declaration of Helsinki and registered with the French Data Protection Authority (CNIL). All patients and donors provided informed consent concerning the retrospective use of their clinical data.

Letermovir use strategy

In period 1, letermovir was not available and was therefore not used. In period 2, letermovir was administered in oral form to all patients at high risk on day 8 posttransplant and continued until day 100 (week 14) after transplantation according to approval. In contrast, letermovir was not systematically administered to patients at low risk during period 2, but because of the change in CMV infection risk over time, letermovir was initiated and continued until day 100 if corticosteroids were used before day 100 after transplantation. In both risk groups, in case of csCMVi, letermovir was discontinued and not resumed. CMV DNA quantification was performed weekly on EDTA-anticoagulated whole blood samples by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction using the kPCR PLX CMV DNA Assay on the Versant kPCR Molecular System (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) until 2018 and, from 2019, the AltoStar CMV PCR Kit 1.5, on the AltoStar Automation System (Altona Diagnostics, Hamburg, Germany). The threshold for use of preemptive therapy in CMV viremia was determined in a consensual manner at 3.5 log10 IU/mL.3,18-20

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were expressed as frequency (percentage). Age was reported as a median with interquartile range. The primary end point was the cumulative incidence of csCMVi defined as the use of preemptive therapy for CMV viremia or CMV disease. The secondary endpoints were the following: cumulative incidence of CMV disease, overall survival (OS) defined as the time from allo-HCT to death, progression-free survival (PFS) defined as the time from allo-HCT to disease progression or death, cumulative incidence of relapse (CIR) defined as the time from allo-HCT to disease progression, and nonrelapse mortality (NRM) defined as the time from allo-HCT to death without evidence of underlying disease relapse.

Comparisons of patient characteristics between the 2 periods were performed using χ2 test or Fisher exact test for categorical variables and Mann–Whitney U test for the age at allo-HCT. The cumulative incidences of csCMVi (with landmark analysis for late csCMVi), CMV disease, relapse, and NRM with 95% confidence interval (CI) were estimated using the Kalbfleisch and Prentice method by considering death as a competing event (except for NRM: relapse) and was compared between the 2 periods (period 1 vs period 2) in each risk group (low- and high-risk) by using the Fine and Gray competing risk regression model. OS and PFS were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared between the 2 periods using the Cox regression model. All analyses were censored at 52 weeks after transplantation. The 14-week cumulative incidence of csCMVi was estimated in subgroups of patients. Heterogeneity tests were performed to assess whether the effect of period on the risk of csCMVi differed based on patient characteristics.

Statistical testing was conducted at the two-tailed α-level of 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, version 9.4).

Results

Study population

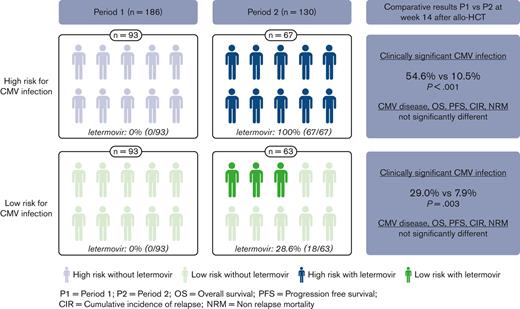

A total of 316 adult patients who were CMV positive underwent allo-HCT from 1 January 2015 to 31 July 2021. Period 1 comprised 186 patients and the period 2 comprised 130 patients (Figure 1). The baseline characteristics of the population and variables used to calculate CMV risk score are presented in Table 1. Median age was 56.0 years (interquartile range 43.5-64.0), and 52.5% of patients were male. Regarding patients and transplantation modalities, period 1 and period 2 were comparable, except for haploidentical transplantations which were slightly less frequent in period 2. According to the CMV risk score, 156 (49.4%) patients were at low risk and 160 (50.6%) at high risk for CMV infection, and this distribution of patients was balanced in both periods (50% vs 50% in period 1 and 48.5% vs 51.5% in period 2). The median follow-up was 59.5 (95% CI 56.5-64.5) months for period 1 and 17.8 (14.3-20.3) months for period 2.

CsCMVi and CMV disease

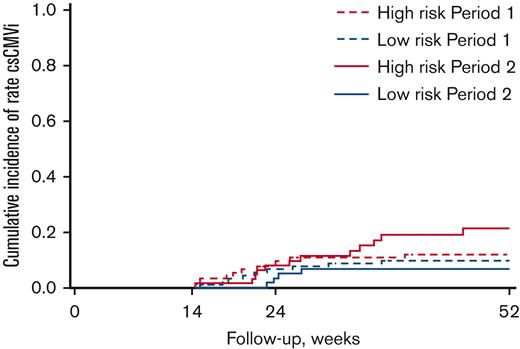

Cumulative incidences of csCMVi and CMV disease based on the risk of CMV infection and period are shown in Figure 2 and Table 2. The median delay between allo-HCT and the first csCMVi was 50 days (range: 12-526). In patients at high risk with systematic use of letermovir in period 2, csCMVi incidence was lower than in period 1 (P < .001) by week 14 after transplantation: 10.5% (95% CI 4.6-19.2) vs 51.6% (41.0-61.3), and beyond week 14 with lower incidences persisting by week 24: 16.9% (8.9-27.0) vs 52.7% (42.0-62.3), and by 1 year after transplantation: 28.2% (17.3-40.2) vs 53.8% (43.0-63.3), respectively. CMV disease was not significantly different (P = .69) between the 2 periods: 0% vs 3.2% (95% CI 0.9-8.4) by week 14, 1.5% (0.1-7.2) vs 4.3% (1.4-9.9) by week 24, and 3.3% (0.6-10.3) vs 4.3% (1.4-9.9) by 1 year after transplantation.

Cumulative incidence of csCMVi according to CMV infection risk and period.

In patients at low risk, no patients received letermovir in period 1 and 18 of 63 patients (28.6%) received letermovir in period 2. Despite this sparing use of letermovir during period 2, the incidence of csCMVi was also significantly lower than that in period 1 (P = .003) by week 14: 7.9% (95% CI 2.9-16.3) vs 29.0% (20.2-38.5), by week 24: 11.2% (4.9-20.5) vs 33.3% (23.9-43.0), and by 1 year after transplantation: 12.9% (6.0-22.6) vs 34.4% (24.9-44.1), respectively. CMV disease was not significantly different (P = .85) between the 2 periods: 0% vs 0% by week 14, 1.7% (95% CI 0.1-8.0) vs 1.1% (0.1-5.3) by week 24, and 1.7% (0.1-8.0) vs 2.2% (0.4-6.9) by 1 year posttransplant.

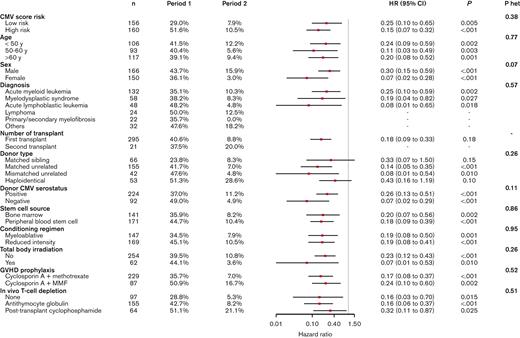

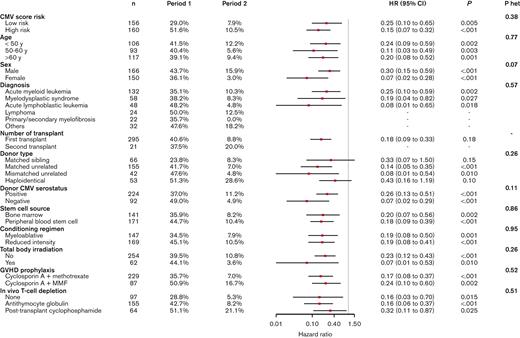

Figure 3 shows the efficacy of letermovir used in period 2 compared to period 1 for preventing csCMVi by week 14, according to subgroups defined by baseline characteristics. All subgroups benefited from letermovir use (nonsignificant heterogeneity) with hazard ratio (HR) consistently < 0.50. The effect of letermovir was more pronounced in patients at high risk: HR = 0.15 (95% CI 0.07-0.32), P < .001 than in patients at low risk: HR = 0.25 (0.10-0.65), P = .005. The most important and significant differences were observed in females: HR = 0.07 (95% CI 0.02-0.28), P < .001 and in patients with CMV-negative donor: HR = 0.07 (0.02-0.29), P < .001.

Letermovir efficacy in preventing csCMVi by week 14 according to subgroups in period 2 compared to period 1.

Letermovir efficacy in preventing csCMVi by week 14 according to subgroups in period 2 compared to period 1.

Sparing use of letermovir in patients at low risk during period 2

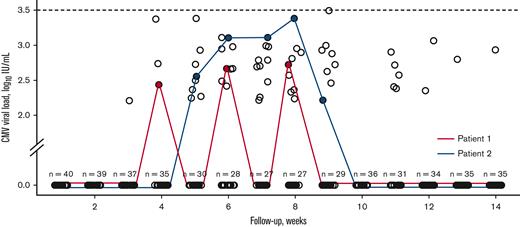

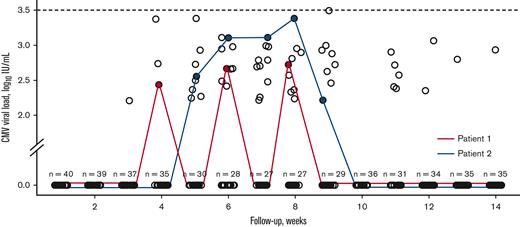

As specified, letermovir was not systematically used in patients at low risk during period 2 (n = 63). On one hand, 18 patients (28.6%) eventually received letermovir because of the use of corticosteroids before week 14, with a median delay of 28 days (range: 16-50) from transplantation before starting letermovir. The reason for initiation of corticosteroids was primarily acute GVHD (aGVHD), except for 2 patients (engraftment syndrome and immune-mediated hemolytic anemia). None of the 18 patients experienced csCMVi. On the other hand, among patients at low risk who did not receive letermovir (n = 45), 5 patients (11.1%) experienced csCMVi by week 14 and were successfully treated with a single course of preemptive therapy without CMV disease. In addition, 23 patients (51.1%) experienced transient positive CMV DNA without csCMVi while 17 (37.8%) never had detectable CMV viral load by week 14. The median time of first detectable CMV DNA was 42 days (range: 21-77) and the median quantifiable CMV viral load was 2.72 IU/mL (range 2.21-3.49). No CMV DNA was found ≥3.5 log10 IU/mL. Figure 4 shows the CMV viral loads of patients at low risk without csCMVi and who did not receive letermovir.

CMV viral loads for patients at low-risk without csCMVi and who did not receive letermovir in period 2. Two patients are depicted and the number of patients without detectable CMV viral load is indicated at each week.

CMV viral loads for patients at low-risk without csCMVi and who did not receive letermovir in period 2. Two patients are depicted and the number of patients without detectable CMV viral load is indicated at each week.

Secondary endpoints

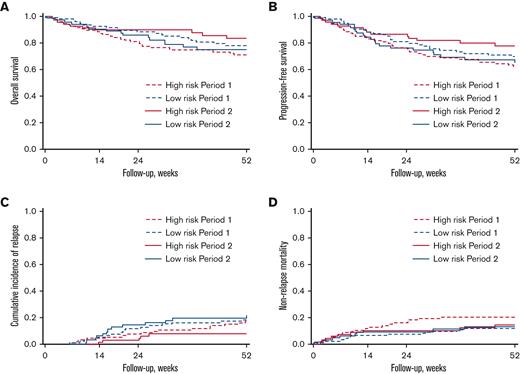

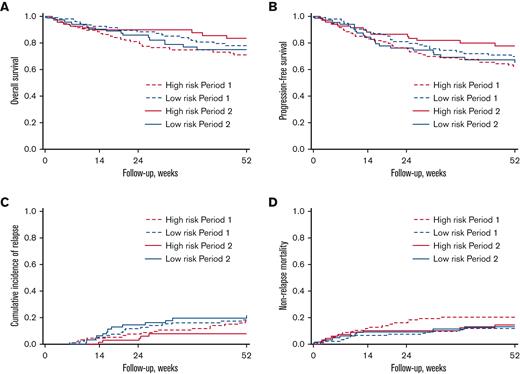

OS, PFS, CIR, and NRM based on the risk of CMV infection and period are shown in Figure 5 and Table 2. In patients at high risk, higher OS in period 2 than in period 1 was found but did not reach a statistically significant level (1-year OS after transplantation: 83.4% [95% CI 71.0-90.8] in period 2 vs 70.9% [60.5-79.0] in period 1, P = .08). A similar result was found for PFS comparing period 2 to period 1 (1-year after transplantation: 77.6% [95% CI 65.0-86.2] vs 62.3% [51.6-71.2] respectively, P = .06). The CIR did not significantly differ across the 2 periods (P = .14) nor did NRM (P = .31). In patients at low risk, no significative differences were observed between the 2 periods for OS (P = .56), PFS (P = .52), CIR (P = .60), and NRM (P = .80).

Kaplan-Meier analysis according to CMV infection risk and period. (A) OS, (B) PFS, (C) CIR, and (D) NRM.

Kaplan-Meier analysis according to CMV infection risk and period. (A) OS, (B) PFS, (C) CIR, and (D) NRM.

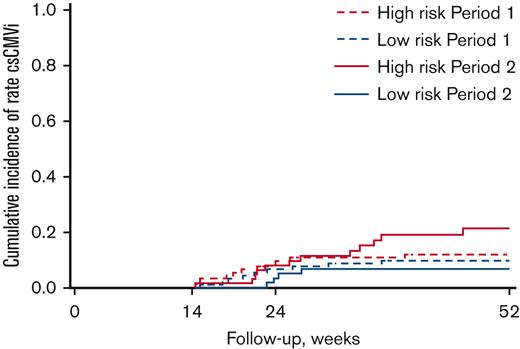

Exploratory end point: late csCMVi (>week 14)

A landmark analysis was performed from week 14 to explore the incidence of CMV infection after the discontinuation of letermovir, whether or not the patient had a prior CMV infection before week 14. In patients at high risk, there was no significant difference in the incidence of late csCMVi between period 2 and period 1 (1 year after transplantation: 21.1% [95% CI 11.5-32.7] in period 2 vs 11.8% [6.2-19.3] in period 1, P = .20). Similarly, among patients at low risk, the incidences of late csCMVi between the 2 periods were not significantly different between period 2 and period 1 (1 year after transplantation: 6.8% [95% CI 2.1-15.1] vs 9.7% [4.7-16.7], P = .52). The cumulative incidences of late csCMVi based on the risk of CMV infection and period are shown in Figure 6. Overall, 36 patients (13 low-risk and 23 high-risk) experienced late csCMVi in both periods. Of the 36 patients, 17 patients (47.2%) had experienced prior csCMVi before week 14, and 23 patients (63.9%) had received corticosteroids after week 14. Reasons of corticosteroids were late-onset aGVHD (n = 10), corticosteroids-refractory aGVHD (n = 5), GVHD after donor lymphocyte infusion (n = 4), overlap syndrome (n = 2), cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (n = 1), and late capillary leak syndrome (n = 1). Only 6 patients (16.7%) had neither prior csCMVi before week 14 nor late corticosteroid use.

Cumulative incidences of late csCMVi (>week 14) according to CMV infection risk and period.

Cumulative incidences of late csCMVi (>week 14) according to CMV infection risk and period.

Discussion

The randomized pivotal trial comparing letermovir with placebo was consistent for the prevention of csCMVi in patients at high and low risk of CMV infection; consequently, the approval was for all patients who were CMV positive and was not based on individual risk of CMV infection.5 It should be noted that in the prophylaxis of fungal infections, voriconazole or posaconazole are labeled in only select patients at high-risk based on randomized phase 3 studies, which however did not consider the individual risk of fungal infection.21,22 Moreover, many studies have shown that the risk of CMV infection depends on transplantation modalities and the characteristics of the donor–recipient pair.12-16 It is therefore reasonable to assume that letermovir would not have the same benefit in all patients. Most of these studies explored the risk factors of CMV infection independently to distinguish between high-risk and low-risk patients. Because risk factors do not have the same strong association with CMV infection, we had previously developed a CMV risk score considering 6 weighted variables at the time of transplantation.17 Using this more sophisticated tool to measure the risk of csCMVi and having a dynamic strategy in patients at low risk receiving corticosteroids, we have shown that sparse use of letermovir in patients at low risk could be achieved resulting in low csCMVi incidence without impairing clinical outcomes as CMV disease, OS, or NRM. Indeed, with 28.6% of the patients at low risk eventually receiving letermovir in period 2, the low incidence of csCMVi by week 14 (7.9%) was similar to that of the letermovir phase 3 study (7.7%) or real-life studies in which letermovir was used in all patients.23-26 The decrease in csCMVi in period 2 compared with that in period 1 was thus explained by the use of letermovir in patients receiving corticosteroids, almost all for aGVHD, which is known to be a major factor in CMV infection.27-30 At the same time, we found an important beneficial of letermovir in patients at high risk in csCMVi prevention with an improved and nearly statistically significant OS through 1 year after transplantation. It seems thus reasonable to assume that a larger number of patients would have allowed for reaching statistical significance. We assume that by focusing on patients at high risk in larger, ideally randomized studies, an additional OS benefit of letermovir could be demonstrated.

Compared with other antiviral drugs tested unsuccessfully in the prophylaxis of CMV infection after allo-HCT, letermovir acts through a unique mechanism of action by inhibiting the viral terminase complex through its binding to pUL56.31-33 Moreover, letermovir is highly specific for CMV, without activity against other herpesviruses or adenovirus.34 This specificity is probably one of the main reasons for its successful use in allo-HCT, in which the side effects often restrict the use of antivirals.35,36 But letermovir, as a P-glycoprotein and an organic anion transporting polypeptide 1B1/3 transporter substrate, a moderate inhibitor of CYP3A, and an inducer of CYP2C9/19, has multiple drug interactions, which might prove a significant point in patients who are polymedicated. The most relevant interactions in the allo-HCT setting are the immunosuppressive drugs (cyclosporine, tacrolimus, and sirolimus) and voriconazole.37,38 Although letermovir dosage reduction (480-240 mg/d) is mandatory if used with cyclosporine and therapeutic monitoring should be carried out for key drugs, the tolerance of letermovir and other coadministered drugs could be challenged, especially in a real-world setting in which patients present potentially more comorbidities. In this context, the benefit-risk balance may be adversely affected in patients at low risk of CMV infection, highlighting the importance of assessing whether letermovir is really needed in this category of patient.

By comparison to HIV-positive patients, the term blips has been used to describe transient episodes of detectable CMV DNA in the blood.10 There has been a long-standing debate about the point at which preventive treatment should be initiated.39 In our study, we systematically used 3.5 log10 IU/mL as the threshold, based on previous studies and recommendations.3,18-20 We showed that a number of patients at low risk not receiving letermovir in period 2 had transient positive CMV viral load but the OS was not affected. In the retrospective study by Green et al7, CMV viral load >250 IU/mL was associated with increased early death (<day 60), but the impact was considerably attenuated after day 60, suggesting that patients in this study with early positive CMV viral load could have been very distinct. Moreover, CMV replication without csCMVi is not necessarily a negative event, and decreased exposure to CMV antigen in patients receiving letermovir has been shown to delay CMV-specific T-cells reconstitution.9,40,41 This delay in the reconstitution of CMV-specific immunity has already been suspected in letermovir phase 3 study with the observation of an increase in csCMVi after the discontinuation of letermovir. One option being considered to address this issue is to extend the letermovir exposure period to 200 days after transplantation (NCT03930615) in patients at high risk for CMV infection. Probably, letermovir at this time may be useful in patients who are still heavily immunocompromised, especially those suffering from GVHD.42 Methods have been developed to quantify specific immune recovery, the main ones being CMV quantiferon and enzyme-linked immunospot, but these approaches are difficult to implement routinely in all centers and standardization with uniform thresholds are still lacking.43-45

To investigate late CMV infection, we performed a landmark analysis from week 14, which allows the analysis of csCMVi occurring after week 14, even if the patient was previously infected. We reported late csCMVi in both risk groups, independent of letermovir use by week 14. Thus, delayed CMV-specific immunity because of letermovir may not be the exclusive cause of late csCMVi. We considered other risk factors in 36 patients with late csCMVi from both risk groups and both time periods. Interestingly, we observed that nearly all these patients had received corticosteroids after week 14 or had experienced a previous csCMVi before week 14. A role for prolonged letermovir exposure after week 14 or even resumption in case of late GVHD, for instance after a donor lymphocyte infusion, could be identified in this specific case of patients with persistent severe immunodeficiency or as a secondary prophylaxis.46 Admittedly, we have only investigated this possibility in an exploratory manner and this assumption would require a specific study. But, overall, a dynamic strategy that adapts to each patient's changing risk could make letermovir more cost-effective. 47,48

Some limitations should be noted. The main one is that patients were not randomized between the routine strategy with letermovir and the risk-based strategy, but using time periods (period 1 and period 2) was an acceptable alternative method because transplantation modalities have not radically changed over time. A single-center study was another limitation: the difficulty of doing a multicenter study being variable in the management of CMV infection between centers. Finally, haploidentical transplants were not included in our CMV risk score and consistently received letermovir in P2, but this strategy seems appropriate given that it has been described as associated with a high risk of CMV infection.49

In conclusion, we showed that a risk-based strategy for the use of letermovir in recipients of allo-HCT who are CMV-positive proves an effective strategy that maintains the strong efficacy of letermovir in patients at high risk but allows some patients at low risk not to use letermovir. A randomized study between routine letermovir use and a risk-based letermovir use strategy would provide a high level of evidence for these findings.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Matthieu Penet for his help in identifying outpatients receiving antiviral treatment. They also thank Rachel Tipton for the English proofreading of this manuscript.

This study was not endorsed by a research grant.

Authorship

Contribution: M. Sourisseau, I.Y.-A. and D.B. designed the study; P.C., M. Srour, A.C., V.C., and L.M. recruited the patients and applied the risk-based letermovir use strategy; E.F., S.A., F.V., and K.F. managed patients for CMV infection; E.K.A. reported viral quantitative data; N.S. reported pharmacological data; M.K. collected clinical data; H.B. performed statistical analysis; M.S. Sourisseau and D.B. wrote the initial draft of the manuscript; and all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: I.Y.-A. and D.B. received an honorarium from Merck & Co, unrelated to this article. E.K.A. received support from Merck & Co to attend HIV conferences. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: David Beauvais, UAM allogreffe de cellules souches hématopoïétiques, CHU Lille, 2 avenue Oscar Lambret, F-59037 Lille Cedex, France; e-mail: david.beauvais@chru-lille.fr.

References

Author notes

Data are available on request from the corresponding author, David Beauvais (david.beauvais@chru-lille.fr).