Key Points

The ubiquitously expressed integral membrane protein tetherin/BST-2 negatively regulates platelet receptor function.

Tetherin/BST-2 directly interacts with surface receptor, to reduce their activation, trafficking, and mobility within membrane microdomains.

Abstract

The reactivity of platelets, which play a key role in the pathogenesis of atherothrombosis, is tightly regulated. The integral membrane protein tetherin/bone marrow stromal antigen-2 (BST-2) regulates membrane organization, altering both lipid and protein distribution within the plasma membrane. Because membrane microdomains have an established role in platelet receptor biology, we sought to characterize the physiological relevance of tetherin/BST-2 in those cells. To characterize the potential importance of tetherin/BST-2 to platelet function, we used tetherin/BST-2−/− murine platelets. In the mice, we found enhanced function and signaling downstream of a subset of membrane microdomain–expressing receptors, including the P2Y12, TP thromboxane, thrombin, and GPVI receptors. Preliminary studies in humans have revealed that treatment with interferon-α (IFN-α), which upregulates platelet tetherin/BST-2 expression, also reduces adenosine diphosphate–stimulated platelet receptor function and reactivity. A more comprehensive understanding of how tetherin/BST-2 negatively regulates receptor function was provided in cell line experiments, where we focused on the therapeutically relevant P2Y12 receptor (P2Y12R). Tetherin/BST-2 expression reduced both P2Y12R activation and trafficking, which was accompanied by reduced receptor lateral mobility specifically within membrane microdomains. In fluorescence lifetime imaging-Förster resonance energy transfer (FLIM-FRET)–based experiments, agonist stimulation reduced basal association between P2Y12R and tetherin/BST-2. Notably, the glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor of tetherin/BST-2 was required for both receptor interaction and observed functional effects. In summary, we established, for the first time, a fundamental role of the ubiquitously expressed protein tetherin/BST-2 in negatively regulating membrane microdomain–expressed platelet receptor function.

Introduction

Platelets are important mediators of thrombosis in both healthy and diseased vessels, which, when activated by blood vessel injury, form hemostatic thrombi. Pathological activation of platelets can induce occlusive thrombosis, resulting in ischemic events such as heart attack and stroke.1 In addition, through their intrinsic ability to store and secrete a multitude of factors, platelets are implicated in the progression of numerous diseases ranging from cancer to viral infection.1,2 Platelet activation is a tightly coordinated process involving the integrated activation of multiple cell surface–expressed receptors. As in other cells, this highly coordinated process is dependent on the localization of a specific repertoire of transducing, enzymatic, and regulatory kinases and phosphatases that shape signaling output.

Membrane microdomains (also known as lipid rafts) are small (10-200 nm), heterogeneous, highly dynamic, ordered membrane domains enriched in cholesterol, sphingolipids, and gangliosides.3,4 These lipid-enriched regions behave as signaling platforms, mediating a host of signal transduction, intracellular vesicle trafficking, cell fate specification, and disease processes. Human platelets express several surface receptors that have functions that are dependent on their expression in membrane microdomains, including the G protein–coupled thromboxane A2 (TP)5 and P2Y12 receptors (P2Y12Rs).6-8 Relatively little is known about the identities of the proteins in platelets or other cells that coordinate surface receptor distribution into membrane microdomains. Furthermore, the importance of such proteins in the regulation of receptor function remains unclear.

Tetherin, also known as bone marrow stromal antigen-2 (BST-2), CD317, or HM1.24 antigen, is an integral membrane protein with a novel topology ubiquitously expressed in a variety of cells. After it was identified as a marker for bone marrow stromal cells9 and various tumor cells,10 it became clear that tetherin/BST-2 is much more widely expressed in a variety of cells, including hepatocytes, pneumocytes, activated T cells, monocytes, plasmacytoid dendritic cells, ducts of major salivary glands, pancreatic and kidney cells, and the vascular endothelium.11 Transcriptome analysis12 has shown that tetherin/BST-2 is also expressed in both human and mouse platelets. Tetherin/BST-2 is associated with a plethora of biological processes, including restriction of enveloped virus release,13 regulation of B-cell growth,14 and organization of membrane microdomains.14,15 Tetherin/BST-2 is a type 2 single-pass transmembrane protein with unusual architecture, comprising a short cytoplasmic tail at the N terminus, followed by a transmembrane (TM) region, a coiled-coil extracellular domain (ED) containing cysteines (C53/C63/C91) that is necessary for stabilizing dimerization, and a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor at the C terminus.16-18 In relation to viral release, this unique molecular structure allows it to physically tether viral membranes to the host cell membrane, thereby retaining the virus on the cell surface.13

In addition to the roles of tetherin/BST-2 in antiviral immunity, we and others have established that it is an organizer of different cellular structures and organelles.15 Work from our laboratory was the first to establish that tetherin/BST-2 is necessary for the maintenance of the apical actin network and microvilli in polarized epithelial cells.17 At the cell surface, tetherin/BST-2 is proposed to decorate the perimeter of membrane microdomains serving as a picket fence linked to the underlying actin cytoskeleton to stabilize and organize these regions. The GPI anchor of tetherin localizes the protein to cholesterol-rich regions of the cell membrane, whereas the TM domain of the protein sits outside these regions.16 Reduced tetherin expression has been suggested to change the distribution of membrane-localized proteins and organization of lipids in the plasma membrane.15

Although tetherin/BST-2 is ubiquitously expressed, the physiological significance of this protein in relation to receptor biology is unclear. We hypothesized that tetherin/BST-2 expression is essential for normal platelet receptor function and demonstrate for the first time that tetherin/BST-2 negatively regulates platelet receptor signaling.

Methods

Materials

All materials and reagents used in this study are described in the supplemental Methods.

Animals

Tetherin/BST-2−/− mice were a kind gift from Paul D. Bieniaz (The Rockefeller University, New York, NY). Tetherin/BST-2 −/−mice were maintained on a mixed C57BL/6 background, and littermates were used as the control, with genotyping of tetherin/BST-2−/−, as previously described.19 All procedures undertaken complied with the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 (licenses 30/2386 and 30/2908) and were approved by the University of Bristol’s local Research Ethics Committee.

Patient-based experiments

Patients with an essential thrombocythemia (ET) diagnosis, according to World Health Organization 2001/2008 diagnostic criteria,20 were enrolled in this study. Four patients had blood samples collected before initiation of interferon-α2b (IFN-α2b) therapy, another 4 were treated with pegylated IFN-α2b (40 µg every other day for 5-23 months). Appropriate informed consent was obtained from all patients before blood was collected, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and under a research protocol approved by the ethics committees of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College.

Platelet aggregation and ATP secretion

Platelet preparation, aggregation, and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) secretion were undertaken as previously described21 and as detailed in the supplemental Methods.

Cell culture and transfection

Both transiently and stably transfected human embryonic kidney (HEK293) cells were used in this study. Cell culture, plasmid construct, and transfection procedures are described in the supplemental Methods.

Measurement of surface protein expression

Platelet surface glycoproteins and thrombin-induced P-selectin expression were measured by flow cytometry with an Accuri C6 flow-cytometer (BD Biosciences), with data analyzed by FACSCalibur.

P2Y1 and P2Y12 surface receptor expression was assessed by ligand binding using [3H]-2MeSADP, as previously described.22 Tagged surface receptors levels were assessed in HEK293 cells by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, as described,23 and receptor recycling was measured by flow cytometry as described.24 Details of the procedures are given in the supplemental Methods.

Coimmunoprecipitation and immunoblot detection

P2Y12R and tetherin/BST-2 interaction was assessed in both cell lines and human platelets by coimmunoprecipitation followed by western blot analysis, as previously described23 and are described in the supplemental Methods.

Assessment of cAMP accumulation in mouse platelets and transfected HEK293 cells

Adenosine diphosphate (ADP)–induced inhibition of forskolin (1 μM)-stimulated cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) accumulation was performed in washed mouse platelets or in transiently transfected HEK293 cells, as previously described.22,25 Data are expressed as the percentage of inhibition of forskolin-stimulated adenylyl cyclase.

Calcium mobilization assay

ADP-induced calcium mobilization was measured in mouse platelets by using the Fura-2 LR/AM calcium indicator in a process described in the supplemental Methods.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

The methods used for preparation of samples (both HEK293 cells and mouse platelets) for subsequent immunofluorescence microscopy are given in detail in the supplemental Methods.

Confocal imaging of platelets or transfected HEK293 cells was performed with a Leica SP8 confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems). Excitation was provided by either a 488-nm (green fluorescent protein [GFP]) or 561-nm (mCherry) laser, and all images were acquired with a 63× 1.4 numeric aperture (NA) oil-immersion objective.

Fluorescence lifetime imaging (FLIM) was performed on a Leica TCS SP8 confocal microscope equipped with a PicoHarp 300 time-correlated, single-photon–counting module (PicoQuant). A white-light laser with a repetition rate of 20 MHz was set at 488 nm for GFP excitation. Images were acquired with a 63× 1.4 NA oil-immersion objective with GFP fluorescence collected from 495 to 530 nm, and data were fitted using FLIMfit.26

Live-cell total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy was performed with a Leica AM TIRF MC system at 37°C in 5% CO2. Excitation was provided by a 488-nm (GFP) or 561-nm (mCherry) laser, and all images were acquired with a 100× 1.47 NA, oil-immersion TIRF microscope objective. Images were captured at 3-second intervals for 1 minute.

Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) was performed on a Leica SP8 confocal microscope. Excitation was provided by either a 488-nm (GFP), a 561-nm (mCherry), or a 633-nm (Alexa 647) laser. Images were acquired with a 100× harmonic compound, plan, apochromat, oil-immersion objective. Photobleaching was performed after 10 prebleaching scans by illuminating a circular 2-µm-diameter spot with the 561-nm laser set to 100% for 5.175 seconds. Images of fluorescence recovery were captured in successive intervals of 1.725 seconds for a duration of 260 seconds. Fluorescence recovery was quantified using ImageJ. The detailed procedures for these imaging methods are available in supplemental Methods.

Modeling

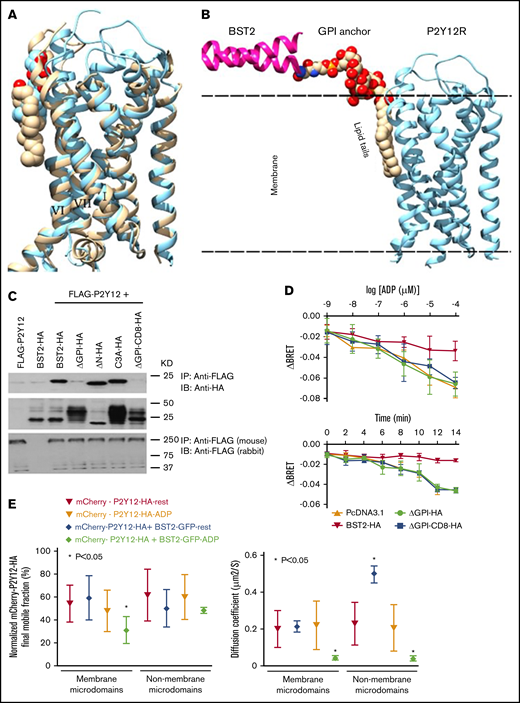

A variant GPI anchor of tetherin/BST-2 was constructed with a palmitoyl and oleoyl phospholipid tail.27 The missing residues from the C terminus of tetherin/BST-2 (Protein Database no. 3NWH) were built in a helical conformation, and the GPI anchor was attached via the acidic group of Ser 160. The palmitoyl and oleoyl tails of the GPI anchor were packed against the P2Y12 structure on the face presented by the transmembrane helices I, VI, and VII of P2Y12 in the positions occupied by oleoyl glycerol in the crystal structure (Protein Database no. 4PXZ).28,29 For clarity, only a single GPI anchor attached to tetherin/BST-2 is shown. The modeling and image generation were performed with Chimera (1.11.2).

Bioluminescence resonance energy transfer measurement

Complementary Rluc-II-Gαi-1 and GFP10-Gγ2 constructs were used to measure G protein activation downstream of receptor stimulation, as described previously30 and detailed in the supplemental Methods.

Statistical analysis

Data analyses and determinations of statistical significance were performed with Prism 7.0 software (GraphPad) and are described in the supplemental Methods.

Results

Does tetherin/BST-2 affect P2Y12R function in platelets?

Platelets express several surface receptors, including the P2Y12R, which necessitates their association with membrane microdomains for optimal function.5-7 We hypothesized that tetherin/BST-2, an established regulator of membrane microdomain organization, could regulate the activity of these receptors. We initially established that tetherin/BST-2 is expressed in both human and mouse platelets by both reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR; Figure 1A) and western blot analysis (Figure 1B). Importantly, tetherin/BST-2 expression was undetectable in tetherin/BST-2−/− mouse platelets, validating both primer and antibody specificity (Figure 1A). There were no obvious differences between wild-type (WT) and tetherin/BST-2−/− mice in major hematologic parameters, including platelet count (supplemental Figure 1A), mean platelet volume, and platelet distribution width (data not shown); the expression of surface glycoproteins (CD41, glycoprotein VI [GPVI], GPI-bα, and PAR-4; supplemental Figure 1B); and the levels and patterns of oligomers, dimers, and monomers of the P2Y12Rs in platelets (supplemental Figure 1C). Ligand binding experiments using [3H]-2MeSADP revealed comparable expression of P2Y12Rs in WT vs tetherin/BST-2−/− platelets (790 ± 59 and 864 ± 83 P2Y12Rs per platelet in WT and tetherin/BST-2−/− platelets).

Tetherin/BST-2 negatively regulates P2Y12R activities in both platelets and cell lines. (A) PCR and RT-PCR were used to genotype mice. RT-PCR was performed on total RNA isolated from BST+/+ and tetherin/BST-2−/− mouse platelets, with primers specific for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase or tetherin/BST-2. (B) Washed platelets from humans or BST-2+/+ and BST-2−/− mice were solubilized and immunoblotted with tetherin/BST-2 or tubulin-specific antibodies. Data are representative of at least 4 independent experiments. (C-D) ADP-stimulated platelet aggregation was significantly enhanced in BST-2−/− vs BST-2+/+ mice in either platelet-rich plasma (PRP) (C) or washed platelets (D). Representative traces of platelet aggregation in PRP or washed platelets are shown and are representative of 5 independent experiments. Data from washed platelets were quantified and expressed as maximum platelet aggregation (right). Data represent mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of 5 independent experiments. Maximum platelet aggregation was significantly enhanced in BST-2−/− vs BST-2+/+ mice. *P < .05; 2-tailed Student t test. (E) P2Y12R activity in BST-2−/− vs BST-2+/+ mouse platelets, as assessed by inhibition of forskolin (1 μM; 10 minutes)-induced cAMP production by ADP (0.1 nM-100 μM; 10 minutes). Data are means ± SEM of 4 independent experiments with ADP-stimulated inhibition of adenylyl cyclase activity significantly enhanced in BST-2−/− vs BST-2+/+ mouse platelets (2-way analysis of variance [ANOVA]; P < .01). (F) ADP (0.1-100 μM)-stimulated calcium responses were unchanged in BST-2+/+ vs BST-2−/− mouse platelets. Data are expressed as peak calcium responses (ratio of 340 nm/380 nm readings with Fura-2) and represent the mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. (G-I) ADP-induced inhibition of forskolin-stimulated cAMP production and ERK1/2 activation were assessed in cells transiently cotransfected with mCherry-HA–tagged P2Y12R and either tetherin/BST-2-GFP or GFP control vectors. (G) In P2Y12R-expressing cells, ADP-induced (0.1 nM-100 μM; 10 minutes) inhibition of forskolin-stimulated (1 μM; 10 minutes) cAMP production was significantly attenuated by tetherin/BST-2-GFP overexpression. P < .01; 2-way ANOVA. Data are the mean ± SEM of 4 independent experiments. (H-I) Activity of ADP (20 μM)-stimulated ERK1/2 activation was also assessed by immunoblot analysis with a p-ERK specific antibody. Total ERK and α-tubulin served as protein-loading controls. (H) Representative blots of at least 4 independent experiments. (I) Data expressed as p-ERK levels normalized to total ERK. Mean ± SEM; n = 4. P2Y12R-stimulated ERK activity was significantly attenuated by tetherin/BST-2-GFP overexpression (*P < .05; 2-way ANOVA). (J) Fluorescence intensity profile of mCherry-HA-P2Y12R surface expression taken from TIRF microscopy images of HEK293 cells coexpressing tetherin/BST-2-GFP or GFP control (n = 6 cells over the course of 6 independent experiments).

Tetherin/BST-2 negatively regulates P2Y12R activities in both platelets and cell lines. (A) PCR and RT-PCR were used to genotype mice. RT-PCR was performed on total RNA isolated from BST+/+ and tetherin/BST-2−/− mouse platelets, with primers specific for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase or tetherin/BST-2. (B) Washed platelets from humans or BST-2+/+ and BST-2−/− mice were solubilized and immunoblotted with tetherin/BST-2 or tubulin-specific antibodies. Data are representative of at least 4 independent experiments. (C-D) ADP-stimulated platelet aggregation was significantly enhanced in BST-2−/− vs BST-2+/+ mice in either platelet-rich plasma (PRP) (C) or washed platelets (D). Representative traces of platelet aggregation in PRP or washed platelets are shown and are representative of 5 independent experiments. Data from washed platelets were quantified and expressed as maximum platelet aggregation (right). Data represent mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of 5 independent experiments. Maximum platelet aggregation was significantly enhanced in BST-2−/− vs BST-2+/+ mice. *P < .05; 2-tailed Student t test. (E) P2Y12R activity in BST-2−/− vs BST-2+/+ mouse platelets, as assessed by inhibition of forskolin (1 μM; 10 minutes)-induced cAMP production by ADP (0.1 nM-100 μM; 10 minutes). Data are means ± SEM of 4 independent experiments with ADP-stimulated inhibition of adenylyl cyclase activity significantly enhanced in BST-2−/− vs BST-2+/+ mouse platelets (2-way analysis of variance [ANOVA]; P < .01). (F) ADP (0.1-100 μM)-stimulated calcium responses were unchanged in BST-2+/+ vs BST-2−/− mouse platelets. Data are expressed as peak calcium responses (ratio of 340 nm/380 nm readings with Fura-2) and represent the mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. (G-I) ADP-induced inhibition of forskolin-stimulated cAMP production and ERK1/2 activation were assessed in cells transiently cotransfected with mCherry-HA–tagged P2Y12R and either tetherin/BST-2-GFP or GFP control vectors. (G) In P2Y12R-expressing cells, ADP-induced (0.1 nM-100 μM; 10 minutes) inhibition of forskolin-stimulated (1 μM; 10 minutes) cAMP production was significantly attenuated by tetherin/BST-2-GFP overexpression. P < .01; 2-way ANOVA. Data are the mean ± SEM of 4 independent experiments. (H-I) Activity of ADP (20 μM)-stimulated ERK1/2 activation was also assessed by immunoblot analysis with a p-ERK specific antibody. Total ERK and α-tubulin served as protein-loading controls. (H) Representative blots of at least 4 independent experiments. (I) Data expressed as p-ERK levels normalized to total ERK. Mean ± SEM; n = 4. P2Y12R-stimulated ERK activity was significantly attenuated by tetherin/BST-2-GFP overexpression (*P < .05; 2-way ANOVA). (J) Fluorescence intensity profile of mCherry-HA-P2Y12R surface expression taken from TIRF microscopy images of HEK293 cells coexpressing tetherin/BST-2-GFP or GFP control (n = 6 cells over the course of 6 independent experiments).

Given the therapeutic relevance of and our longstanding interest in P2Y12R biology,22,23,25,31 we first focused on whether tetherin/BST-2 regulates P2Y12R function. We observed that ADP-stimulated platelet aggregation was significantly enhanced in tetherin/BST-2−/− vs littermate control WT mouse platelets (example aggregation traces in platelet rich plasma [PRP; Figure 1C]) and washed platelets, with averaged data showing the percentage of maximum aggregation in washed platelets [Figure 1D]). Intriguingly, in washed platelets at a higher ADP concentration (10 µM), platelet aggregation was not affected in tetherin/BST-2−/− mice, indicative that the effect of tetherin/BST-2 knockout was surmountable. To further explore this point, we assessed ADP-stimulated platelet signaling. Given that ADP activates both the Gq-coupled P2Y1 and Gi-coupled P2Y12Rs to stimulate platelet aggregation, we assessed signaling outputs downstream of each receptor. ADP-induced inhibition of forskolin-stimulated adenylyl cyclase was significantly enhanced in tetherin/BST-2−/− platelets, with an increase in both the maximum response and leftward shift of the concentration-response curve (Figure 1E). In contrast, there was no change in ADP-induced intracellular calcium responses, which was largely mediated by the G-coupled P2Y1R, in WT vs tetherin/BST-2−/− platelets (Figure 1F). These data suggest that tetherin/BST-2 selectively negatively regulates P2Y12R activity in mouse platelets.

Pilot experiments in human platelets next examined whether changes in tetherin/BST-2 expression had the potential to affect ADP-stimulated platelet receptor function. ET is a classic BCR-ABL1− myeloproliferative neoplasm characterized by overproduction of mature platelets accompanied by an increased risk of thrombosis with a risk of major thrombotic events in patients that ranges from 10% to 29%.32 IFN-α therapy is an approach to treatment of ET that represses the proliferation of hematopoietic progenitors, primarily to control platelet counts, thereby reducing the risk of thrombosis without increasing the tendency to bleed.33 Notably, IFN treatment upregulates tetherin/BST-2 expression in various cell types across multiple species, including humans.34 We therefore assessed platelet tetherin/BST-2 levels and ADP-induced platelet aggregation in 4 enrolled patients with ET before and after IFN therapy (supplemental Figure 2). Because IFN treatment decreases the number of platelets, we normalized our platelet count (3.0 × 108 cells per milliliter) in our subsequent experiments, thereby ensuringchanges in platelet reactivity did not occur because of changes in the number of platelets. IFN therapy increased tetherin/BST-2 expression (supplemental Figure 2A, representative blot from 1 patient; supplemental Figure 2B, quantified data across patients). Along with this increase in tetherin/BST-2 expression, IFN treatment significantly attenuated ADP-stimulated platelet reactivity (supplemental Figure 2C, representative aggregation traces; supplemental Figure 2D, across patients). Although preliminary in nature, these data suggest that tetherin/BST-2 negatively regulates ADP-stimulated platelet activity in humans.

To further explore tetherin/BST-2-dependent regulation of the P2Y12R we expressed both proteins in HEK293 cells. HEK293 cells were specifically used, as they are tetherin/BST-2 null,15 enabling the clear establishment of the effects of tetherin/BST-2 expression on receptor function. Notably, tetherin/BST-2 expression significantly reduced downstream P2Y12R activity with reductions in both ADP-stimulated inhibition of adenylyl cyclase activity (Figure 1G) and ERK1/2 phosphorylation (Figure 1H, representative blot; Figure 1I, quantified data). TIRF microscopy was used to measure changes in mCherry-HA-P2Y12 surface expression in HEK293 cells transiently cotransfected with mCherry-HA-P2Y12R and either BST-2-GFP or GFP vector control (Figure 1J). As in mouse platelets, changes in tetherin/BST-2 expression did not significantly affect P2Y12R surface expression (Figure 1J). These data further confirmed that tetherin/BST-2 negatively regulates P2Y12R activity.

Does tetherin/BST-2 colocalize and functionally interact with the P2Y12R?

Initial confocal microscopy in mouse platelets spread on fibrinogen revealed that tetherin/BST-2 colocalized with the P2Y12R (representative images Figure 2A, with image analysis showing pixel intensity histograms of gray scale images for both the green and red channels (Figure 2B) and colocalization (Figure 2D). A more detailed understanding of tetherin/BST-2 colocalization was provided by experiments on HEK293 cells coexpressing tetherin/BST-2-GFP and mCherry-HA–tagged P2Y12Rs. Confocal microscopy indicated that these proteins predominantly associated at the cell membrane (Figure 2C, representative images; Figure 2D, imaging analysis). The agonist dependence of any potential receptor and tetherin/BST-2 interaction was then assessed by immunoprecipitation, first in HEK293 cells and then in human platelets. Cells were treated with ADP (20 μM; 0, 5, 30, and 60 minutes) solubilized, and anti-HA immunoprecipitation was performed. Subsequent immunoblot analysis revealed a specific association of P2Y12R with tetherin/BST-2, which was significantly attenuated by receptor activation (Figure 2E-F). Washed human platelets were treated with ADP (10 μM; 30 minutes) and lysed, and anti-P2Y12R immunoprecipitation was performed. Subsequent immunoblot analysis revealed a specific association of the P2Y12R with tetherin/BST-2, which as in the cell lines, was significantly attenuated by receptor activation (Figure 2G).

Colocalization and interaction of tetherin/BST-2 with P2Y12R. Tetherin/BST-2 colocalized with the P2Y12R in (A-B,D) mouse platelets and (B-C) HEK293 cells. (A) Representative confocal images of permeabilized mouse platelets spread on fibrinogen and treated with rat anti-mouse tetherin/BST-2 and rabbit anti-P2Y12, followed by anti-rat Alexa 488 (green)– and anti-rabbit Alexa 546 (red)–conjugated secondary antibodies. Bar represents 10 µm. (B) Pixel intensity histograms of gray scale images (A; bottom) corresponding to output from green and red channels (A; top). (C) HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with tetherin/BST-2-GFP alone or with either mCherry or mCherry-HA-P2Y12R. Fixed cell samples were prepared for subsequent confocal microscopy. Representative confocal images of HEK293 cells coexpressing BST-2-GFP (green) and mCherry (red; top), GFP and mCherry-P2Y12-HA (middle), or BST-2-GFP and mCherry-P2Y12-HA (bottom). Bar represents 1 μm. Images from panels A and C underwent subsequent quantitative analysis (C; n = 16 for platelet and n = 22 for HEK293 cells, across 3 independent experiments). (D) Pearson’s correlation coefficients (PCCs) in either platelets or in the whole cell vs the membrane or cytoplasm of the cell. The PCCs were significantly higher in membranes vs either the whole cell or cytoplasm. *P < .05; Student t test. (E-F) HEK293 cells cotransfected with mCherry-HA-P2Y12 and either tetherin/BST-GFP or GFP control were treated with ADP (20 μM; 0-60 minutes). The cells were lysed, and the receptors were immunoprecipitated with monoclonal mouse anti-HA-agarose. (E) The samples were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and immunoblotted for associated anti-GFP (top) and reprobed with an anti-HA antibody to show the total receptor immunoprecipitated (second gel). Inputs were immunoblotted for GFP (third gel) and anti-α-tubulin to show equal protein loading. Gels are representative of 3 independent experiments. (F) Quantification of tetherin/BST-2 coimmunoprecipitated with P2Y12R. Data are normalized relative to association of tetherin/BST-2 with P2Y12R at rest vs agonist stimulated and expressed as means ± standard error of the mean (n = 3; *P < .05, Mann-Whitney U test). (G) The P2Y12R was immunoprecipitated from control or ADP-treated, washed platelets (10 µM; 30 minutes) with a receptor-specific rabbit antibody, as outlined in “Methods.” Immunocomplexes were resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-BST-2 antibody (top gel). Inputs were immunoblotted for P2Y12R (second gel), BST-2 (third gel), and anti-α-tubulin (bottom gel) to show equal protein loading.

Colocalization and interaction of tetherin/BST-2 with P2Y12R. Tetherin/BST-2 colocalized with the P2Y12R in (A-B,D) mouse platelets and (B-C) HEK293 cells. (A) Representative confocal images of permeabilized mouse platelets spread on fibrinogen and treated with rat anti-mouse tetherin/BST-2 and rabbit anti-P2Y12, followed by anti-rat Alexa 488 (green)– and anti-rabbit Alexa 546 (red)–conjugated secondary antibodies. Bar represents 10 µm. (B) Pixel intensity histograms of gray scale images (A; bottom) corresponding to output from green and red channels (A; top). (C) HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with tetherin/BST-2-GFP alone or with either mCherry or mCherry-HA-P2Y12R. Fixed cell samples were prepared for subsequent confocal microscopy. Representative confocal images of HEK293 cells coexpressing BST-2-GFP (green) and mCherry (red; top), GFP and mCherry-P2Y12-HA (middle), or BST-2-GFP and mCherry-P2Y12-HA (bottom). Bar represents 1 μm. Images from panels A and C underwent subsequent quantitative analysis (C; n = 16 for platelet and n = 22 for HEK293 cells, across 3 independent experiments). (D) Pearson’s correlation coefficients (PCCs) in either platelets or in the whole cell vs the membrane or cytoplasm of the cell. The PCCs were significantly higher in membranes vs either the whole cell or cytoplasm. *P < .05; Student t test. (E-F) HEK293 cells cotransfected with mCherry-HA-P2Y12 and either tetherin/BST-GFP or GFP control were treated with ADP (20 μM; 0-60 minutes). The cells were lysed, and the receptors were immunoprecipitated with monoclonal mouse anti-HA-agarose. (E) The samples were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and immunoblotted for associated anti-GFP (top) and reprobed with an anti-HA antibody to show the total receptor immunoprecipitated (second gel). Inputs were immunoblotted for GFP (third gel) and anti-α-tubulin to show equal protein loading. Gels are representative of 3 independent experiments. (F) Quantification of tetherin/BST-2 coimmunoprecipitated with P2Y12R. Data are normalized relative to association of tetherin/BST-2 with P2Y12R at rest vs agonist stimulated and expressed as means ± standard error of the mean (n = 3; *P < .05, Mann-Whitney U test). (G) The P2Y12R was immunoprecipitated from control or ADP-treated, washed platelets (10 µM; 30 minutes) with a receptor-specific rabbit antibody, as outlined in “Methods.” Immunocomplexes were resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-BST-2 antibody (top gel). Inputs were immunoblotted for P2Y12R (second gel), BST-2 (third gel), and anti-α-tubulin (bottom gel) to show equal protein loading.

To further assess how P2Y12R activation affected interaction with tetherin/BST-2, we used quantitative Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET)-based FLIM (FRET-FLIM).26 In these assays, we assessed fluorescence lifetime in HEK293 cells transiently cotransfected with tetherin/BST-2-GFP and either mCherry-HA-P2Y12R or mCherry vector control. Given that our data suggested that the P2Y12R predominantly colocalized with tetherin/BST-2 at the plasma membrane, our FLIM images were segmented into the plasma membrane (Figure 3A) and cytoplasm (supplemental Figure 3). We focused on the plasma membrane section (Figure 3A). Coexpression of tetherin/BST-2-GFP and mCherry-HA-P2Y12R led to a significant reduction of fluorescence life of the FRET donor in the plasma membrane compared with tetherin/BST-2-GFP alone or the tetherin/BST-2-GFP+mCherry control (Figure 3A-B; representative images and pooled data, respectively). These data further demonstrate that the P2Y12R is in close proximity to and most likely directly interacts with tetherin/BST-2. Notably, receptor activation by ADP (20 μM; 5, 30, and 60 minutes) increased donor life. This effect was reversed by removal of ADP by treatment with apyrase (5 minutes; 1 U/mL; 60 minutes with apyrase; Figure 3B). These data again suggest that receptor activation reduced association with tetherin/BST-2. To further understand the mechanism of agonist-mediated impaired association of P2Y12R with tetherin/BST-2, single-cell analysis of the intensity of intracellular tetherin/BST-2-GFP and mCherry-HA-P2Y12Rs was undertaken (Figure 3C-E). Cell images captured before FLIM were segmented for analysis (Figure 3C). The intracellular intensity of P2Y12R increased after application of the agonist. The increased intensity was reversed after removal of ADP by addition of apyrase (Figure 3D). Tetherin/BST-2 levels meanwhile remained relatively constant (Figure 3E) indicating that receptor activation promoted membrane dissociation of P2Y12R-tetherin/BST-2 complex, with subsequent receptor internalization.

Tetherin/BST-2 interacts directly with the P2Y12R. HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with tetherin/BST-2-GFP (FRET donor) alone or with either mCherry or mCherry-HA-P2Y12R (FRET acceptor). Cells coexpressing tetherin/BST-2 and P2Y12R were stimulated with ADP (20 μM; 0-60 minutes) or with ADP (20 μM; 60 minutes), followed by the addition of apyrase (1 U/mL) for 5 minutes. Fixed cell samples were prepared for subsequent microscopy. (A) Representative fluorescence intensity (gray scale images, top) and corresponding intensity-weighted (pseudocolor, bottom) images of cell membranes at selected time points of measurement. (B) Fluorescence life measurements of tetherin/BST-2-GFP from cell membrane regions showing association of P2Y12R with tetherin/BST-2. Coexpression of tetherin/BST-2-GFP (donor) with mCherry-HA-P2Y12R (acceptor) significantly reduced donor vs mCherry life (*P < .05; Student t test) indicative of protein proximity. Addition of ADP (5, 30, and 60 minutes) significantly increased donor life vs the non–agonist-treated control (§P < .05; Student t test) or after apyrase removal of ADP (€; P < .05; Student t test). (C-E) Agonist-induced changes in P2Y12R and tetherin/BST-2 intracellular expression were assessed, and the data were normalized and expressed as a percentage of whole-cell fluorophore intensity. (C) Cell images captured before FLIM were segmented in CellProfiler by using a semiautomatic approach. Identified objects were subsequently reduced in size by 10% to produce complementary masks to define the cell edge and central regions. ADP treatment had no effect on tetherin/BST-2 intracellular expression (D), but promoted a significant increase in intracellular accumulation of the P2Y12R vs non–agonist-treated control (*P < .05; Student t test) or after apyrase removal of ADP (P < .05; Student t test; E). (B,D-E) Data points represent a single cell (n > 12 per transfection condition) pooled across 3 independent experiments with line and error bars representing means ± standard error of the mean .

Tetherin/BST-2 interacts directly with the P2Y12R. HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with tetherin/BST-2-GFP (FRET donor) alone or with either mCherry or mCherry-HA-P2Y12R (FRET acceptor). Cells coexpressing tetherin/BST-2 and P2Y12R were stimulated with ADP (20 μM; 0-60 minutes) or with ADP (20 μM; 60 minutes), followed by the addition of apyrase (1 U/mL) for 5 minutes. Fixed cell samples were prepared for subsequent microscopy. (A) Representative fluorescence intensity (gray scale images, top) and corresponding intensity-weighted (pseudocolor, bottom) images of cell membranes at selected time points of measurement. (B) Fluorescence life measurements of tetherin/BST-2-GFP from cell membrane regions showing association of P2Y12R with tetherin/BST-2. Coexpression of tetherin/BST-2-GFP (donor) with mCherry-HA-P2Y12R (acceptor) significantly reduced donor vs mCherry life (*P < .05; Student t test) indicative of protein proximity. Addition of ADP (5, 30, and 60 minutes) significantly increased donor life vs the non–agonist-treated control (§P < .05; Student t test) or after apyrase removal of ADP (€; P < .05; Student t test). (C-E) Agonist-induced changes in P2Y12R and tetherin/BST-2 intracellular expression were assessed, and the data were normalized and expressed as a percentage of whole-cell fluorophore intensity. (C) Cell images captured before FLIM were segmented in CellProfiler by using a semiautomatic approach. Identified objects were subsequently reduced in size by 10% to produce complementary masks to define the cell edge and central regions. ADP treatment had no effect on tetherin/BST-2 intracellular expression (D), but promoted a significant increase in intracellular accumulation of the P2Y12R vs non–agonist-treated control (*P < .05; Student t test) or after apyrase removal of ADP (P < .05; Student t test; E). (B,D-E) Data points represent a single cell (n > 12 per transfection condition) pooled across 3 independent experiments with line and error bars representing means ± standard error of the mean .

Tetherin/BST-2-dependent regulation of P2Y12R surface expression

ADP-induced P2Y12R dissociation with BST-2/tetherin and subsequent internalization were further confirmed with TIRF microscopy by measuring fluorescence changes of BST-2-GFP and mCherryP2Y12-HA in 150-nm penetration depth of the membranes of cells transiently cotransfected with mCherry-HA-P2Y12R and either BST-2-GFP or GFP vector control (Figure 4A-D). There was a gradual but significant agonist-stimulated reduction in P2Y12R surface levels over time (Figure 4A-C), whereas tetherin/BST-2-GFP surface expression remained constant (Figure 4A-B,D). Furthermore, in cells coexpressing P2Y12R and tetherin/BST-2-GFP, agonist-stimulated loss of surface receptors was attenuated (Figure 4C).

Tetherin/BST-2 negatively regulates P2Y12R internalization in both cell lines and mouse platelets. (A) Representative live TIRF microscopy images of HEK293 cells coexpressing mCherry-HA-P2Y12R (red) and either GFP control (green; top) or tetherin/BST-2-GFP before (green; middle) and after agonist stimulation (ADP; 20 μM; 60 minutes; green; bottom). (B) Fluorescence intensity profiles from lines shown in images from panel A assessing either mCherry (receptor) or GFP (either control or tetherin/BST-2) surface expression. (C-D) A time course series (0-60 minutes) of the intensity profiles was assessed (n = 6 cells over the course of 6 independent experiments), and the ADP-stimulated change in surface mCherry-HA-P2Y12R (C) or tetherin/BST-2-GFP (D) was quantified (percentage change after agonist stimulation; mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM]). (E) Assessment of FLAG-P2Y12R recycling by flow cytometry. Receptor-expressing cells prelabeled with anti-FLAG(M1)-FITC were stimulated with ADP (20 μM; 60 minutes). Surface antibody and ADP were removed by washing with a Ca2+-free buffer containing apyrase (0.2 U/mL). P2Y12R recycling was then monitored by flow cytometry. Data represent percentage of recycled P2Y12R (*P < .05; 1-way analysis of variance [ANOVA]). (F-G) P2Y12, but not P2Y1R internalization, was negatively regulated by tetherin/BST-2 in mouse platelets. BST-2−/− and BST-2+/+ mouse platelets were stimulated with ADP (10 μM). P2Y1 and P2Y12 surface receptor levels were measured in fixed, washed platelets, with[3H]-2MeSADP (100 nM) in the presence of either the P2Y1R antagonist A3P5P (1 mM) or the P2Y12R antagonist AR-C69931MX (1 μM). Data are expressed as a percentage of surface receptor and represent means ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. P2Y12 but not P2Y1R surface loss was potentiated in BST-2−/− vs BST-2+/+ mouse platelets (P < .05; 2-way ANOVA).

Tetherin/BST-2 negatively regulates P2Y12R internalization in both cell lines and mouse platelets. (A) Representative live TIRF microscopy images of HEK293 cells coexpressing mCherry-HA-P2Y12R (red) and either GFP control (green; top) or tetherin/BST-2-GFP before (green; middle) and after agonist stimulation (ADP; 20 μM; 60 minutes; green; bottom). (B) Fluorescence intensity profiles from lines shown in images from panel A assessing either mCherry (receptor) or GFP (either control or tetherin/BST-2) surface expression. (C-D) A time course series (0-60 minutes) of the intensity profiles was assessed (n = 6 cells over the course of 6 independent experiments), and the ADP-stimulated change in surface mCherry-HA-P2Y12R (C) or tetherin/BST-2-GFP (D) was quantified (percentage change after agonist stimulation; mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM]). (E) Assessment of FLAG-P2Y12R recycling by flow cytometry. Receptor-expressing cells prelabeled with anti-FLAG(M1)-FITC were stimulated with ADP (20 μM; 60 minutes). Surface antibody and ADP were removed by washing with a Ca2+-free buffer containing apyrase (0.2 U/mL). P2Y12R recycling was then monitored by flow cytometry. Data represent percentage of recycled P2Y12R (*P < .05; 1-way analysis of variance [ANOVA]). (F-G) P2Y12, but not P2Y1R internalization, was negatively regulated by tetherin/BST-2 in mouse platelets. BST-2−/− and BST-2+/+ mouse platelets were stimulated with ADP (10 μM). P2Y1 and P2Y12 surface receptor levels were measured in fixed, washed platelets, with[3H]-2MeSADP (100 nM) in the presence of either the P2Y1R antagonist A3P5P (1 mM) or the P2Y12R antagonist AR-C69931MX (1 μM). Data are expressed as a percentage of surface receptor and represent means ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. P2Y12 but not P2Y1R surface loss was potentiated in BST-2−/− vs BST-2+/+ mouse platelets (P < .05; 2-way ANOVA).

The P2Y12R is efficiently and rapidly recycled to the cell surface in platelets.22 To investigate whether these tetherin/BST-2-regulated changes in surface P2Y12R levels are caused by a defect in receptor internalization or a potentiation of receptor recycling, a recycling assay was used with FLAG-tagged-P2Y12R.24 In this assay, the receptor is prelabeled, with a calcium sensitive FLAG antibody (M1) and agonist added to stimulate receptor internalization. The surface-bound FLAG antibody is then stripped by a calcium-free wash, and the recycling of internal FLAG-P2Y12R is monitored by fluorescence-activated cell sorting after removal of the agonist. FLAG-P2Y12R efficiently recycled to the cell surface, with tetherin/BST-2-GFP expression having no effect, suggesting that tetherin/BST-2 had little effect on the recycling of P2Y12Rs (Figure 4E). Therefore, tetherin/BST-2 is the likely regulator of P2Y12R internalization.

In agreement with these experiments in HEK293 cells, ligand-binding experiments in mouse platelets showed that agonist-induced P2Y12R surface loss was potentiated in tetherin/BST-2−/− mice (Figure 4F). Meanwhile, agonist-induced P2Y1R surface loss in mouse platelets was unaffected by changes in tetherin (Figure 4G). These data further confirm that tetherin/BST-2 selectively and negatively regulates specific receptors.

What is the molecular basis of the tetherin/BST-2: P2Y12R interaction?

We next explored the molecular determinants of tetherin/P2Y12R interaction. The recently solved crystal structure of the P2Y12R revealed significant levels of cholesterol packed around the receptor that are suggested to help pack the receptor in high-order oligomers.28 Molecular modeling of the P2Y12R with tetherin/BST-2 revealed the potential for the C-terminal GPI anchor of tetherin/BST-2 to displace this cholesterol, potentially affecting receptor function (Figure 5A-B). We therefore explored the potential importance of the GPI anchor of tetherin/BST-2 in HEK293 cells by coexpressing FLAG-tagged P2Y12R with either full-length HA-tagged WT tetherin/BST-2 (WT-HA) or a series of previously described15 tetherin/BST-2 deletion constructs (Figure 5C). These included truncations lacking either the N-terminal region (ΔN-HA) or the GPI anchor (ΔGPI-HA) of tetherin. A further construct (C3A-HA), in which 3 critical cysteine residues that stabilize tetherin/BST-2 dimer formation through disulphide bonds are changed to alanines, was also tested.15 FLAG-P2Y12R was coimmunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG affinity gel and HA-tetherin/BST-2 interaction assessed by western blot. As expected, the P2Y12R associated with WT-HA. Interestingly, only the removal of the GPI anchor of tetherin/BST-2 was found to disrupt receptor interaction. To exclude the possibility that the loss of interaction was due to minimal ΔGPI-HA mutant surface expression, we assessed receptor interaction with a tetherin/BST-2 construct in which the GPI anchor was replaced by the CD8α transmembrane domain (ΔGPI-CD8α-HA), to mimic the topology of WT tetherin/BST-2 at the cell surface.15 Again ΔGPI-CD8α-HA did not interact with P2Y12R. The GPI anchor of tetherin/BST-2 therefore is critical for receptor interaction. Given that the ΔGPI-CD8α-HA construct is unlikely to be localized to membrane microdomains,35 we suggest that the GPI anchor is critical for tetherin/BST-2 localization in P2Y12R-containing membrane microdomains and for direct interaction with P2Y12R.

The GPI anchor of tetherin/BST-2 is needed to regulate P2Y12R function. (A) An overlay of the P2Y12R crystal structures: antagonist bound (wheat, 4NTJ)x28 and agonist bound (cyan,4PXZ)xx.29 Protein structures are shown as ribbons, and cholesterol (wheat) and 1-oleoyl-R-glycerol (cyan) are shown in space-filling representations. TM-helices binding these lipids are labeled I, VI, and VII. (B) A model of the tetherin/BST-2-GPI interaction with P2Y12R. C-terminal part of tetherin/BST-2, magenta ribbon; GPI anchor in space-filling representations with the lipid tails in the membrane packed against agonist-bound P2Y12R, shown as cyan ribbon. Molecular modeling showing potential interaction between tetherin/BST-2 and the P2Y12R. (C) The GPI anchor of tetherin/BST-2 is necessary for P2Y12R interaction. HEK293 cells were transfected with FLAG-P2Y12 alone or in combination with a variety of HA-tagged constructs, including full-length tetherin/BST-2, 2 truncations lacking either the N-terminal region (ΔN-HA) or the GPI anchor (ΔGPI-HA) of tetherin/BST-2, tetherin/BST-2 triple cysteine→alanine mutant (C3A-HA), or a tetherin/BST-CD8 construct in which the GPI anchor has been replaced by the CD8α transmembrane domain (ΔGPI-CD8-HA). Cells were lysed, and the receptor was immunoprecipitated by using monoclonal mouse anti-FLAG M2 Affinity Gel. Samples were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblotted for associated anti-HA (top gel). Inputs were immunoblotted for anti-HA to show protein loading (middle gel) and immunoprecipitates reprobed with anti-FLAG antibody (rabbit) to show the total receptor immunoprecipitated (bottom gel). (D) The GPI anchor of tetherin/BST-2 is essential for tetherin/BST-2–dependent regulation of P2Y12R activity. HEK293 cells were cotransfected with 2:1:1 ratios of Gi protein constructs (Rluc-II-tagged Gαi-1/Gβ1/GFP10-tagged Gγ2), FLAG-P2Y12R and either HA-tagged tetherin/BST-2 constructs (HA-WT, ΔGPI-HA or CD8-ΔGPI-HA) or pcDNA3.1 control. P2Y12R activity was assessed by agonist-stimulated changes in BRET between Gαi-1-Rluc-II and GFP10-Gγ2 in living cells. Data are expressed as ΔBRET by subtracting the BRET values obtained in the vehicle condition from the one measured with ADP and represent mean ± standard error of the mean of 4 independent experiments. Shown are concentration-dependence of P2Y12R activation (ADP; 1 nM-100 µM; top) and time-dependent activation of the P2Y12R by ADP (20 µM; bottom). Only full-length tetherin/BST-2-HA expression attenuated P2Y12R activity (both top and bottom; *P < .05; 2-way ANOVA tetherin/BST-2 vs pDNA3.1 control). (E) Tetherin/BST-2 attenuatedP2Y12R mobility in membrane microdomains after receptor activation, as assessed by FRAP. HEK293 cells expressing mCherry-HA-P2Y12R alone or coexpressing mCherry-P2Y12-HA and BST-2-GFP, were stained with the membrane microdomain marker cholera toxin-B (CTB). Confocal FRAP was performed at 37°C in live cells with a 2-μm diameter bleach spot (supplemental Figure 4B) on CTB+ (yellow circles) or negative regions (cyan circles) of the cell membrane. FRAP was subsequently assessed. In agonist-treated cells ADP (20 µM) was added 5 minutes before FRAP. Data were collected from >9 cells from 3 independent experiments and are expressed as either the percentage of normalized mCherry-P2Y12-HA final mobile fraction (left) or the diffusion coefficient (mm2/s; right). Tetherin/BST-2 expression significantly attenuated P2Y12R mobility into CTB+ membrane microdomain regions in ADP-treated cells (left; *P < .05 Mann-Whitney U test in tetherin/BST-2 expressing vs nonexpressing cells in membrane microdomains in ADP-treated cells (right); *P < .05; Student t test; tetherin/BST-2–expressing vs nonexpressing cells in membrane microdomains in ADP-treated cells).

The GPI anchor of tetherin/BST-2 is needed to regulate P2Y12R function. (A) An overlay of the P2Y12R crystal structures: antagonist bound (wheat, 4NTJ)x28 and agonist bound (cyan,4PXZ)xx.29 Protein structures are shown as ribbons, and cholesterol (wheat) and 1-oleoyl-R-glycerol (cyan) are shown in space-filling representations. TM-helices binding these lipids are labeled I, VI, and VII. (B) A model of the tetherin/BST-2-GPI interaction with P2Y12R. C-terminal part of tetherin/BST-2, magenta ribbon; GPI anchor in space-filling representations with the lipid tails in the membrane packed against agonist-bound P2Y12R, shown as cyan ribbon. Molecular modeling showing potential interaction between tetherin/BST-2 and the P2Y12R. (C) The GPI anchor of tetherin/BST-2 is necessary for P2Y12R interaction. HEK293 cells were transfected with FLAG-P2Y12 alone or in combination with a variety of HA-tagged constructs, including full-length tetherin/BST-2, 2 truncations lacking either the N-terminal region (ΔN-HA) or the GPI anchor (ΔGPI-HA) of tetherin/BST-2, tetherin/BST-2 triple cysteine→alanine mutant (C3A-HA), or a tetherin/BST-CD8 construct in which the GPI anchor has been replaced by the CD8α transmembrane domain (ΔGPI-CD8-HA). Cells were lysed, and the receptor was immunoprecipitated by using monoclonal mouse anti-FLAG M2 Affinity Gel. Samples were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblotted for associated anti-HA (top gel). Inputs were immunoblotted for anti-HA to show protein loading (middle gel) and immunoprecipitates reprobed with anti-FLAG antibody (rabbit) to show the total receptor immunoprecipitated (bottom gel). (D) The GPI anchor of tetherin/BST-2 is essential for tetherin/BST-2–dependent regulation of P2Y12R activity. HEK293 cells were cotransfected with 2:1:1 ratios of Gi protein constructs (Rluc-II-tagged Gαi-1/Gβ1/GFP10-tagged Gγ2), FLAG-P2Y12R and either HA-tagged tetherin/BST-2 constructs (HA-WT, ΔGPI-HA or CD8-ΔGPI-HA) or pcDNA3.1 control. P2Y12R activity was assessed by agonist-stimulated changes in BRET between Gαi-1-Rluc-II and GFP10-Gγ2 in living cells. Data are expressed as ΔBRET by subtracting the BRET values obtained in the vehicle condition from the one measured with ADP and represent mean ± standard error of the mean of 4 independent experiments. Shown are concentration-dependence of P2Y12R activation (ADP; 1 nM-100 µM; top) and time-dependent activation of the P2Y12R by ADP (20 µM; bottom). Only full-length tetherin/BST-2-HA expression attenuated P2Y12R activity (both top and bottom; *P < .05; 2-way ANOVA tetherin/BST-2 vs pDNA3.1 control). (E) Tetherin/BST-2 attenuatedP2Y12R mobility in membrane microdomains after receptor activation, as assessed by FRAP. HEK293 cells expressing mCherry-HA-P2Y12R alone or coexpressing mCherry-P2Y12-HA and BST-2-GFP, were stained with the membrane microdomain marker cholera toxin-B (CTB). Confocal FRAP was performed at 37°C in live cells with a 2-μm diameter bleach spot (supplemental Figure 4B) on CTB+ (yellow circles) or negative regions (cyan circles) of the cell membrane. FRAP was subsequently assessed. In agonist-treated cells ADP (20 µM) was added 5 minutes before FRAP. Data were collected from >9 cells from 3 independent experiments and are expressed as either the percentage of normalized mCherry-P2Y12-HA final mobile fraction (left) or the diffusion coefficient (mm2/s; right). Tetherin/BST-2 expression significantly attenuated P2Y12R mobility into CTB+ membrane microdomain regions in ADP-treated cells (left; *P < .05 Mann-Whitney U test in tetherin/BST-2 expressing vs nonexpressing cells in membrane microdomains in ADP-treated cells (right); *P < .05; Student t test; tetherin/BST-2–expressing vs nonexpressing cells in membrane microdomains in ADP-treated cells).

To further explore whether the GPI anchor is necessary for tetherin/BST-2 regulation of P2Y12R signaling, we monitored receptor/G-protein activation by a standard bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET)–based approach that measures agonist-stimulated changes in Gα/βγ disassociation by the functionally validated BRET pair Rluc-II-Gαi-1 and GFP10-Gγ2.36 Upon receptor activation, Rluc-II-Gαi-1 and GFP10-Gγ2 rapidly disassociated, leading to a decrease in ΔBRET signal (Figure 5D). As expected, tetherin/BST-2 expression significantly reduced P2Y12R-stimulated changes in G-protein activation (Figure 5D). Expression of either ΔGPI-HA or ΔGPI-CD8α-HA constructs had no effect on P2Y12R activity, confirming the requirement of the GPI anchor of tetherin/BST-2 to regulate receptor function.

Our molecular modeling suggested that the GPI anchor of tetherin/BST-2 could displace cholesterol, which influences membrane integrity and modulates membrane fluidity.37 Could the potential displacement of this cholesterol affect P2Y12R activity by changing local membrane fluidity and limit the conformational freedom of the receptor? To investigate, we performed FRAP experiments to examine P2Y12R membrane mobility inside and outside of membrane microdomains in the absence or presence of tetherin/BST-2. We used cholera toxin subunit B (CT-B) conjugated to Alexa Fluor 647 which binds to the pentasaccharide chain of the plasma membrane ganglioside GM-1, enabling selective partitioning into membrane microdomains (supplemental Figure 4A). We therefore photobleached mCherry-HA-P2Y12R+ regions of transfected HEK293 cells, focusing on CT-B+ or CT-B− regions of the plasma membrane and assessed mCherry-HA-P2Y12R FRAP (supplemental Figure 4B).

Notably, tetherin/BST-2 expression significantly reduced agonist-stimulated P2Y12R mobility in membrane microdomains (either the percentage of fluorescence recovery [supplemental Figure 4C] or the mobile fraction/diffusion coefficient [Figure 5E]). Intriguingly, tetherin/BST-2 expression appeared to enhance basal, agonist-independent P2Y12R mobility outside membrane microdomains although, as in CT-B+ regions, tetherin expression slowed agonist-dependent receptor mobility. We therefore conclude that tetherin/BST-2 regulates P2Y12R lateral mobility in the plasma membrane, decreasing agonist-stimulated lateral diffusion. Because the effective and coordinated lateral membrane movement of GPCRs is necessary for effective localization proximal to specific downstream signaling proteins, we suggest that tetherin/BST-2 in part negatively regulates receptor signaling by effecting this process.

Does tetherin/BST-2 affect membrane microdomain–expressed receptor signaling beyond the P2Y12R?

Thus far, our data have demonstrated that tetherin/BST-2 selectively regulate P2Y12 but not P2Y1R surface expression and function in platelets. Beyond the P2Y12R, the optimal function of several platelet-expressed surface receptors is commensal in their expression in membrane microdomains. The collagen-receptor GPVI38 and the G-protein–coupled TP receptor5 have been shown to be associated with membrane microdomains, whereas there is evidence that the thrombin-stimulated PAR4 receptor associates with P2Y12.11 Notably, platelet aggregation was enhanced in tetherin/BST-2−/− platelets after activation of the PAR4 (Figure 6A, representative trace), TP (Figure 6B, representative trace) or GPVI receptor (Figure 6C, representative trace; Figure 6D, mean data for all agonists showing the percentage of maximum aggregation vs littermate control W) mouse platelets). We also assessed platelet-dense granule secretion by measuring ATP release. The level of secretion of all 3 receptors in tetherin/BST-2−/− platelets was also enhanced (Figure 6A-C, representative traces, bottom; Figure 6E, quantified data). Enhanced agonist-stimulated ATP secretion was not related to increased total levels of ATP in secretory granules in tetherin/BST-2−/− platelets (supplemental Figure 1D).

Tetherin/BST-2 negatively regulates other membrane microdomain–expressed receptor functions in mouse platelets. Thrombin (A)-, TP thromboxane (B)-, and CRP (C)-stimulated platelet aggregation was significantly enhanced in BST-2−/− vs BST-2+/+ mice in washed platelets. Representative traces from 3 independent experiments showing platelet aggregation (top) and ATP secretion (bottom) in response to thrombin in the absence and presence of the P2Y12 receptor antagonist (ARC66096; 10 μM), U46619 or CRP. (D-E) Data were quantified and expressed as maximum aggregation (D) and ATP secretion (E). Data represent mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of 3 independent experiments. *P < .05; 2-tailed Student t test. (F) Platelet α-granule secretion was assessed by measuring thrombin (0.03 μ/mL)-stimulated P-selectin expression by flow cytometry. Data represent mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. *P < .05; 2-tailed Student t test.

Tetherin/BST-2 negatively regulates other membrane microdomain–expressed receptor functions in mouse platelets. Thrombin (A)-, TP thromboxane (B)-, and CRP (C)-stimulated platelet aggregation was significantly enhanced in BST-2−/− vs BST-2+/+ mice in washed platelets. Representative traces from 3 independent experiments showing platelet aggregation (top) and ATP secretion (bottom) in response to thrombin in the absence and presence of the P2Y12 receptor antagonist (ARC66096; 10 μM), U46619 or CRP. (D-E) Data were quantified and expressed as maximum aggregation (D) and ATP secretion (E). Data represent mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of 3 independent experiments. *P < .05; 2-tailed Student t test. (F) Platelet α-granule secretion was assessed by measuring thrombin (0.03 μ/mL)-stimulated P-selectin expression by flow cytometry. Data represent mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. *P < .05; 2-tailed Student t test.

Thrombin- and GPVI-dependent platelet activation is in part related to the stimulation of P2YRs after secretion.39 We therefore asked whether the enhancement of both CRP- and thrombin-stimulated platelet aggregation and ATP secretion would be maintained if we antagonized the P2Y12R. As expected, antagonism of the P2Y12R with ARC66096 (10 µM) completely abolished CRP (0.4 µM)-stimulated platelet aggregation and secretion (data not shown) and partially reduced thrombin-stimulated platelet aggregation (Figure 6A, example trace, top; Figure 6D, quantified data) and secretion (Figure 6A, example trace, bottom and Figure 6E, quantified data). Importantly, thrombin-stimulated platelet aggregation and secretion in the presence of ARC66096 continued to be enhanced in tetherin/BST-2−/− platelets. We also assessed thrombin-induced P-selectin exposure at the platelet surface to study whether tetherin modulates platelet α-granule secretion. There was a significant increase in thrombin-stimulated P-selectin presented at the platelet surface in tetherin/BST-2−/− vs WT platelets (Figure 6E). Therefore, in summary, our experiments revealed tetherin/BST-2 to be a negative regulator of the activity of a series of putative membrane-microdomain–localized receptors.

Discussion

Membrane microdomains play an established role in receptor biology. For example, in platelets, the P2Y127 and TP receptors,5 which amplify platelet activation when stimulated, are both associated with membrane microdomains. The integral membrane protein tetherin/BST-2, an established restriction factor for enveloped viruses, stabilizes membrane microdomains and alters both lipid and protein distribution within the plasma membrane.14 In this study, we showed, for the first time, a fundamental role of this ubiquitously expressed protein in negatively regulating platelet receptor function. Tetherin/BST-2 regulates the activity of several receptors, with the function of P2Y12, PAR, TP, and GPVI receptors enhanced in tetherin/BST-2−/− mice. Notably, this effect of tetherin is receptor specific, with no changes in the function of receptors (eg, P2Y1R) that are not found in these membrane microdomains. Furthermore, in relation to cardiovascular disease, we demonstrated in patients that IFN treatment upregulates platelet expression of tetherin/BST-2 with an accompanying reduction in platelet reactivity.

Our detailed molecular experiments demonstrated a complex mode of action of tetherin/BST-2 that in part requires the C-terminal GPI anchor of the protein and involves changes in surface receptor mobility. Biochemical fractionation, receptor immunoprecipitation, and confocal imaging techniques demonstrated that there was constitutive association between the P2Y12R and tetherin/BST-2 in both cells and, importantly, in human platelets. Through a FRET-FLIM approach, we demonstrated that surface association between receptor and tetherin/BST-2 is reversibly reduced in the presence of agonist. After disassociation, tetherin/BST-2 remained at the cell surface, whereas P2Y12R was internalized. We have previously established that the P2Y12R interacts with a range of intracellular binding partners, after phosphorylation of G-protein–coupled receptor kinase, which coordinates receptor internalization via a clathrin-mediated pathway.40 Detailed further study is now needed to understand the relationship between tetherin/BST-2 and its effect on P2Y12R interaction with other regulatory binding partners.

Results of molecular modeling experiments suggested that the GPI anchor of tetherin/BST-2 plays a role in receptor interaction, with 3 TM helices (I, VI, and VII) of the P2Y12R potentially involved in interaction with the GPI anchor. Intriguingly, these are the same helices that showed the most perturbation between the agonist- and antagonist-bound crystal structures. We speculate, therefore, that tetherin/BST-2 modulates the conformational freedom of the P2Y12R to perturb agonist responsiveness. However, it should be kept in mind that these regions of the P2Y12R are involved in receptor dimerization in the antagonist-bound crystal structure, although we have no evidence of significant changes in levels of receptor oligomerization.

The key role of the GPI anchor of tetherin/BST-2 in receptor interaction was confirmed in mutagenesis experiments. Could the GPI anchor of tetherin displace cholesterol from membrane microdomains to affect P2Y12R activity? Cholesterol depletion from cell membranes is known to attenuate P2Y12R activity.6 Notably, the crystal structure of the P2Y12R indicates that cholesterol packs around the receptor to maintain conformational integrity.28 However, given that the GPI anchor is also necessary for effective localization of tetherin/BST-2 to membrane microdomains, we can at this time only speculate that displacement of cholesterol by the GPI anchor of tetherin/BST-2 is a direct regulator of P2Y12R activity.

Intriguingly, we found that tetherin/BST-2 expression limited agonist-stimulated lateral diffusion of the P2Y12R within membrane microdomains. Expression of high-order oligomeric complexes containing the P2Y12R in membrane microdomains is necessary for effective receptor signaling.6 Given that agonist-stimulated internalization is necessary to maintain P2Y12R signaling,22 does tetherin/BST-2 limit the movement of non–desensitized receptors into or desensitized receptors out of membrane microdomains? Two studies have established that the lateral distribution and mobility of receptors in the membrane plane bring signaling partners efficiently into transient or stable contact.41,42 Various models of GPCR membrane organization and associated trajectories have been suggested with receptors that freely diffuse over long distances in the membrane.43 However, their movement is also restricted within membrane microdomains. Further detailed study is now needed to investigate movement of P2Y12Rs and whether the formation by tetherin/BST-2 of a physical barrier or picket fence linked to the underlying actin cytoskeleton at the perimeter of membrane microdomains is critical for function.

Our experiments in mouse platelets and cell lines have therefore established tetherin/BST-2 as a regulator of receptor function. Previous studies have demonstrated that patients who receive IFN, which is used in the treatment of a variety of clinical conditions, including ET, leads to an upregulation of tetherin/BST-2 expression in various cell types.13 Intriguing pilot studies in human platelets showed that IFN treatment of patients with ET increased tetherin/BST-2 expression was accompanied by decreased ADP-stimulated platelet reactivity. ET is characterized by overproduction of mature platelets and an increased risk of thrombosis.32 The goals of cytoreductive therapy for ET are primarily to reduce the risk of thrombosis without increasing the tendency toward bleeding and to minimize the risk of progression to myelofibrosis or acute leukemia.32 The results of our pilot study suggest that IFN reduces risk of thrombosis, not only by decreasing the number of platelets, but also by directly attenuating their function. There are reported reductions in platelet reactivity after administration of IFN for the treatment of melanoma44 and hepatitis C,45 with the suggestion that reductions in platelet reactivity limit platelet participation in disease progression (ie, by limiting the inflammatory process involved in hepatitis C or by reducing or preventing the formation of melanoma metastases). In addition, given the effects on platelet reactivity, it should be noted that IFN treatment could have implications in the event of accidental injury or elective surgery. Clearly, this notion requires further extensive study, well beyond the scope of this current work.

In summary, these findings have broad implications for our understanding of platelet receptor signaling from the membrane microdomain, indicating that tetherin/BST-2 plays a key role in regulating output from these sites and may represent a useful therapeutic target for regulating platelet receptor and therefore platelet reactivity.

Original data may be obtained by e-mail request to the corresponding author (s.j.mundell@bristol.ac.uk).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by British Heart Foundation Project Grants PG/13/94/30594 (X.Z.) and PG/17/62/33190 (J.K.); Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (CAMS) Key Laboratory of Gene Therapy for Blood Disease (2017PT31047, China); and CAMS Initiative for Innovative Medicine (2016-12M-1-018; 2017-12M-1-015, China).

Authorship

Contribution: X.Z. designed and performed the research, analyzed and interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript; D.A. designed the FRET-FLIM and FRAP assays and analyzed and interpreted the data; T.S. designed the clinical experiments and analyzed and interpreted the data; J.L.H. developed the calcium assay and collected and analyzed the data; J.K., K.O., R. Seager, R.A., C.M.M., and D.P. analyzed and interpreted the data; C.M.W. and Y.L. performed the in vivo thrombus formation experiment and collected and analyzed the data; R. Sessions designed the molecular modeling experiments and analyzed and interpreted the data; S.C. performed the statistical analyses; A.L. developed the TIRF experiment; L.Z. designed and supervised the clinical experiments and analyzed and interpreted the data; A.W.P. and G.B. jointly supervised the research, analyzed and interpreted the data, and revised the manuscript; S.J.M. designed and supervised the research, analyzed and interpreted the data, and was a joint author of the manuscript; and all authors critically revised the manuscript and approved the final version.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Stuart J. Mundell, University of Bristol, Pharmacology and Neuroscience, School of Physiology, Biomedical Sciences Building, University Walk, Bristol BS8 1TD, United Kingdom; e-mail: s.j.mundell@bristol.ac.uk.

References

Author notes

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

![Tetherin/BST-2 negatively regulates P2Y12R activities in both platelets and cell lines. (A) PCR and RT-PCR were used to genotype mice. RT-PCR was performed on total RNA isolated from BST+/+ and tetherin/BST-2−/− mouse platelets, with primers specific for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase or tetherin/BST-2. (B) Washed platelets from humans or BST-2+/+ and BST-2−/− mice were solubilized and immunoblotted with tetherin/BST-2 or tubulin-specific antibodies. Data are representative of at least 4 independent experiments. (C-D) ADP-stimulated platelet aggregation was significantly enhanced in BST-2−/− vs BST-2+/+ mice in either platelet-rich plasma (PRP) (C) or washed platelets (D). Representative traces of platelet aggregation in PRP or washed platelets are shown and are representative of 5 independent experiments. Data from washed platelets were quantified and expressed as maximum platelet aggregation (right). Data represent mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of 5 independent experiments. Maximum platelet aggregation was significantly enhanced in BST-2−/− vs BST-2+/+ mice. *P < .05; 2-tailed Student t test. (E) P2Y12R activity in BST-2−/− vs BST-2+/+ mouse platelets, as assessed by inhibition of forskolin (1 μM; 10 minutes)-induced cAMP production by ADP (0.1 nM-100 μM; 10 minutes). Data are means ± SEM of 4 independent experiments with ADP-stimulated inhibition of adenylyl cyclase activity significantly enhanced in BST-2−/− vs BST-2+/+ mouse platelets (2-way analysis of variance [ANOVA]; P < .01). (F) ADP (0.1-100 μM)-stimulated calcium responses were unchanged in BST-2+/+ vs BST-2−/− mouse platelets. Data are expressed as peak calcium responses (ratio of 340 nm/380 nm readings with Fura-2) and represent the mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. (G-I) ADP-induced inhibition of forskolin-stimulated cAMP production and ERK1/2 activation were assessed in cells transiently cotransfected with mCherry-HA–tagged P2Y12R and either tetherin/BST-2-GFP or GFP control vectors. (G) In P2Y12R-expressing cells, ADP-induced (0.1 nM-100 μM; 10 minutes) inhibition of forskolin-stimulated (1 μM; 10 minutes) cAMP production was significantly attenuated by tetherin/BST-2-GFP overexpression. P < .01; 2-way ANOVA. Data are the mean ± SEM of 4 independent experiments. (H-I) Activity of ADP (20 μM)-stimulated ERK1/2 activation was also assessed by immunoblot analysis with a p-ERK specific antibody. Total ERK and α-tubulin served as protein-loading controls. (H) Representative blots of at least 4 independent experiments. (I) Data expressed as p-ERK levels normalized to total ERK. Mean ± SEM; n = 4. P2Y12R-stimulated ERK activity was significantly attenuated by tetherin/BST-2-GFP overexpression (*P < .05; 2-way ANOVA). (J) Fluorescence intensity profile of mCherry-HA-P2Y12R surface expression taken from TIRF microscopy images of HEK293 cells coexpressing tetherin/BST-2-GFP or GFP control (n = 6 cells over the course of 6 independent experiments).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodadvances/5/7/10.1182_bloodadvances.2020003182/1/m_advancesadv2020003182f1.png?Expires=1765092770&Signature=tcK7Gk1n9s93vF9KL6FZtfKAq2RpNKvlx7ZyABbrAucGo6bbjlD4gehqTNCEpUOI-ZlnkRJhvCaWAiF1ztBCHwy45Jqb0njarWnGoEHTDqZ29cZDC3cVz~8B73YfnJSDgCmjtAeTc3WGwc-YWo2s0uRbJhcJMuNy1r2eMLFh4QyIwdaaJIbhRwuunki8DhsuhPu7LMZq3mYLtmX6~kGmVCsVMHeng2hppCY1e0dMpLsMsong~wmz6ncNHku-a3yMUEQDbWj1o2CqMkcWTQYxPgOpGwEsVRjLxJ1Ds0~rOeVFk79qBC3n3h7mhy1qiJoQvkCZQQCu7~kqN7WoYGSUrw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Tetherin/BST-2 negatively regulates P2Y12R internalization in both cell lines and mouse platelets. (A) Representative live TIRF microscopy images of HEK293 cells coexpressing mCherry-HA-P2Y12R (red) and either GFP control (green; top) or tetherin/BST-2-GFP before (green; middle) and after agonist stimulation (ADP; 20 μM; 60 minutes; green; bottom). (B) Fluorescence intensity profiles from lines shown in images from panel A assessing either mCherry (receptor) or GFP (either control or tetherin/BST-2) surface expression. (C-D) A time course series (0-60 minutes) of the intensity profiles was assessed (n = 6 cells over the course of 6 independent experiments), and the ADP-stimulated change in surface mCherry-HA-P2Y12R (C) or tetherin/BST-2-GFP (D) was quantified (percentage change after agonist stimulation; mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM]). (E) Assessment of FLAG-P2Y12R recycling by flow cytometry. Receptor-expressing cells prelabeled with anti-FLAG(M1)-FITC were stimulated with ADP (20 μM; 60 minutes). Surface antibody and ADP were removed by washing with a Ca2+-free buffer containing apyrase (0.2 U/mL). P2Y12R recycling was then monitored by flow cytometry. Data represent percentage of recycled P2Y12R (*P < .05; 1-way analysis of variance [ANOVA]). (F-G) P2Y12, but not P2Y1R internalization, was negatively regulated by tetherin/BST-2 in mouse platelets. BST-2−/− and BST-2+/+ mouse platelets were stimulated with ADP (10 μM). P2Y1 and P2Y12 surface receptor levels were measured in fixed, washed platelets, with[3H]-2MeSADP (100 nM) in the presence of either the P2Y1R antagonist A3P5P (1 mM) or the P2Y12R antagonist AR-C69931MX (1 μM). Data are expressed as a percentage of surface receptor and represent means ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. P2Y12 but not P2Y1R surface loss was potentiated in BST-2−/− vs BST-2+/+ mouse platelets (P < .05; 2-way ANOVA).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodadvances/5/7/10.1182_bloodadvances.2020003182/1/m_advancesadv2020003182f4.png?Expires=1765092770&Signature=Vzr6E7MyriioEynQr2rjozzKqubitObpSoOFua5iRnlQ-nlOOh1YjSEcKWXrSNHL8Fe2Xup7zdhYcGt7U6Kum-qriQGsM4jo3eiEAqNFAAKdu4s3kqq-D6zw-~-C4gY1ORiqPCJk8ssn5x3r0aGHHEe-8~laSbJxcCsuljiFC~0tq0ldB1U6j8bhgrImV~Kmm~Q9L26fXtB8X20C5mL7ooL~e8CkupKyOuhkkqJ~EoUN8XOlxyZ6HdSScl2zLy8dVWe1-Lmozsc6PE7kvqv7frtee4fgINNKSJZF4bEncLiijyjMxoueP8uZK2t3MoDFnTPd4jTZrmJtKQOMpx71Tg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)