Key Points

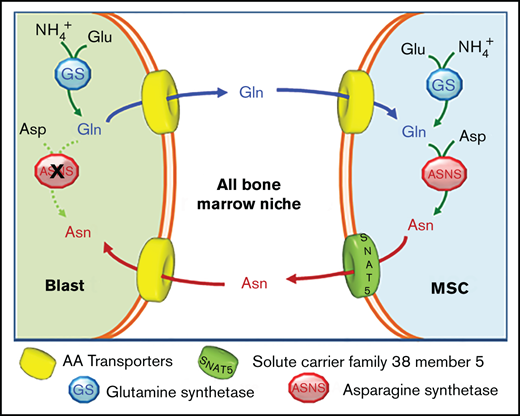

MSCs from ALL patients protect ALL blasts from L-asparaginase better than MSCs from healthy donors through a trade-off of Gln and Asn.

The SNAT5 carrier and GS are needed for the amino acid exchange and their inhibition enhances L-asparaginase effects.

Abstract

Mechanisms underlying the resistance of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) blasts to l-asparaginase are still incompletely known. Here we demonstrate that human primary bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) successfully adapt to l-asparaginase and markedly protect leukemic blasts from the enzyme-dependent cytotoxicity through an amino acid trade-off. ALL blasts synthesize and secrete glutamine, thus increasing extracellular glutamine availability for stromal cells. In turn, MSCs use glutamine, either synthesized through glutamine synthetase (GS) or imported, to produce asparagine, which is then extruded to sustain asparagine-auxotroph leukemic cells. GS inhibition prevents mesenchymal cells adaptation to l-asparaginase, lowers glutamine secretion by ALL blasts, and markedly hinders the protection exerted by MSCs on leukemic cells. The pro-survival amino acid exchange is hindered by the inhibition or silencing of the asparagine efflux transporter SNAT5, which is induced in mesenchymal cells by ALL blasts. Consistently, primary MSCs from ALL patients express higher levels of SNAT5 (P < .05), secrete more asparagine (P < .05), and protect leukemic blasts (P < .05) better than MSCs isolated from healthy donors. In conclusion, ALL blasts arrange a pro-leukemic amino acid trade-off with bone marrow mesenchymal cells, which depends on GS and SNAT5 and promotes leukemic cell survival during l-asparaginase treatment.

Introduction

In the majority of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) patients, leukemic blasts express low asparagine synthetase (ASNS) levels and depend upon the availability of extracellular asparagine (Asn).1,2 For this reason, L-asparaginase has been a cornerstone of ALL therapy for many years. The antileukemic effect of l-asparaginase is mainly attributed to the depletion of extracellular Asn, causing a severe nutritional stress in ALL blasts, although additional mechanisms have also been proposed.3 For example, if blasts express sizable levels of ASNS, l-asparaginase efficacy depends on its glutaminase activity.4 However, Asn and glutamine (Gln) are metabolically related, since Gln is the obliged substrate of ASNS,5 and the 2 amino acids share several membrane transporters.6

Although l-asparaginase led to a substantial improvement of ALL therapy, leukemic cells may become resistant to the enzyme.7 The adaptive induction of ASNS, triggered by the amino acid deprivation caused by l-asparaginase, was proposed as the basis for resistance,8 but the poor correlation existing between ASNS expression levels and patient sensitivity to l-asparaginase9,10 has suggested that additional factors are involved. In fact, ALL blasts become l-asparaginase resistant through a complex process, which involves multiple metabolic adaptations11 and the overexpression12 or downregulation13 of several genes.

Moreover, other cells in the bone marrow niche could actively contribute to l-asparaginase resistance of ALL blasts. Macrophages promote a rapid clearance of l-asparaginase, thus providing protection to ALL blasts during the treatment with the drug.14 Immortalized human mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) exert a strong, ASNS-dependent protective effect on l-asparaginase-treated leukemic cells attributable to Asn secretion.15,16 Consistently, aspartate concentration in bone marrow blood increases during l-asparaginase treatment in vivo,17 as expected from the hydrolysis of secreted neosynthetized Asn by l-asparaginase.18 Thus, the protection from l-asparaginase implies Asn efflux,19 although the transporters involved were not identified. In murine models, adipocytes protect ALL cells through the release of Gln, and protection is hampered by methionine-l-sulfoximine (MSO), an inhibitor of glutamine synthetase (GS).20 However, the ALL line used is more sensitive to Gln depletion than to Asn deprivation, so the role of GS in the bone marrow niche of ASNS-negative ALL blasts remains to be defined.

In this study, using primary human MSCs from the bone marrow of ALL patients or healthy donors, we demonstrate that the nutritional support to leukemic cells depends on an amino acid trade-off, where ALL blasts exploit GS to produce Gln, which is used by mesenchymal cells to synthetize Asn, then extruded to support Asn-auxotrophic ALL blasts. Moreover, we identify the system N transporter SNAT5 as the carrier responsible for Asn efflux from stromal cells and the enhanced protective ability of MSCs derived from leukemia patients. Consistently, GS or SNAT5 inhibition increases l-asparaginase toxicity on ALL cells.

Materials and methods

Reagents

Erwinia chrysanthemi asparaginase (E.C. 3.5.1.1) was gifted by Jazz Pharmaceutics and was used at 1 U/mL. Methionine-l-sulfoximine and the SNAT5 inhibitor l-glutamic acid γ-monohydroxamate were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Other reagents are detailed in supplemental Table 1.

Primary cells

Primary B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (BCP-ALL) blasts were isolated at diagnosis from bone marrow aspirates of UPN#1-10 (6 females and 4 males, see supplemental Table 2) by Ficoll (GE Healthcare) gradient separation and cryopreserved in liquid phase nitrogen until usage.

Human mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) were isolated at diagnosis from the bone marrow of UPN#6-19 BCP-ALL patients (ALL-MSCs, 5 females and 9 males) as described previously.21 MSCs were isolated also from the bone marrow of 17 healthy donors (HD-MSCs; 4 females, 11 males and 2 N/A). All BCP-ALL patients were enrolled in the Associazione Italiana di Ematologia e Oncologia Pediatrica & Berlin-Frankfurt-Münster ALL 2009 protocol (EudraCT-2007-004270-43), while enrolled HDs were stem cell donors whose bone marrow was collected for transplant purposes (BCP-ALL/NICHE protocol, approved by “Comitato Etico Brianza” Ethical Committee). Informed consent to participate in the study was obtained for all the BCP-ALL patients and healthy donors in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All samples were collected at the Pediatric Department of Fondazione Monza e Brianza per il bambino e la sua mamma/San Gerardo Hospital (Monza, Italy).

For mesenchymal cells isolation, bone marrow mononuclear cells were grown in low-glucose Dulbecco’s modified medium (DMEM, EuroClone) supplemented with 2 mM Gln, 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), and antibiotics (100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin). After 48 hours, nonadherent cells were removed from the culture by washing with Ca-Mg-free phosphate-buffered saline(PBS) (Euroclone). When 70% to 80% confluence was achieved, adherent spindle-shaped cells were harvested using .05% trypsin-EDTA (Euroclone) and used for further expansion. After 3 passages (P3), mesenchymal immunophenotype was evaluated by flow cytometry using the following antibodies: mouse anti-human CD45, CD54, CD73, MHC-I and MHC-II (BD Pharmingen); mouse anti-human CD14, CD90, CD105 (eBioscience); mouse anti-human CD34 (BD Biosciences). Cells were positive for CD73, CD90, CD105, CD54, and MHC-I and negative for the other markers (supplemental Figure 1A). All the MSCs strains were further evaluated in terms of differentiation potential (see supplemental Methods and supplemental Figure 1B). For the experiments, mesenchymal cells were not used for >7 passages.

Cell line

The pre-B ALL cell line RS4;11 (female, ATCC CRL-1873, RRID:CVCL_0093) was obtained from ATCC and cultured in low-glucose DMEM supplemented with 2 mM Gln, 400 μM Asn, 10% FBS and antibiotics, at a cell density of 5·105 cells/mL. After thawing, cells were used for <10 passages. The biological identity of the cell line was analyzed by cell surface phenotyping (flow cytometry, FACS Canto II, BD Bioscience) and detection of the cell-specific translocation. The cell line resulted positive for CD15/33/65/66b, CD9, CD19, HLA-DR, CD24, CD45, and negative for CD10.

Co-cultures between ALL cells and MSCs

MSCs were seeded at 25·103 cells/cm2, after 24 hours RS4;11 cells (5·105/mL) or primary BCP-ALL blasts (5·105/mL) were seeded on stromal cells monolayers or maintained alone, and incubated with or without l-asparaginase (1 U/mL) in the absence or presence of methionine-l-sulfoximine (1 mM), l-histidine (10 mM) and l-glutamic acid γ-monohydroxamate (1mM). After 48 hours, cells were harvested, and viability of leukemic cells was assessed by flow cytometry.

For gene expression, RS4;11 (1·106) cells or primary ALL blasts (6·106) were directly added on a MSC monolayer or suspended in the apical compartment of a transwell insert (Costar Transwell Permeable Supports, Corning Inc., pore size 0.4 μm) in asparagine-free DMEM, supplemented with 2 mM Gln and 2% FBS. After 72 hours, ALL cells or blasts were collected from the apical chamber of the transwell insert or after extensive washing with PBS, while stromal cells were collected using trypsin. Total RNA were extracted from both MSC and ALL fractions using TRIzol (Invitrogen) following manufacturer’s instructions.

Flow cytometry

RS4;11 cells were incubated with a monoclonal antibody anti-human CD45-FITC (10µl/1·106, Beckman Coulter Cat# A07782, RRID:AB_10645157) for 30 minutes at RT in the dark, then washed with PBS and suspended in propidium iodide staining buffer (final concentration, 2.5 µg/mL). After 15 minutes at RT, cells were analyzed using an Epics XL flow cytometer and with the Expo ADC software (Beckman Coulter). As gating strategy, RS4;11 cells were selected as CD45 expressing cells, then the necrotic fraction was determined from propidium positivity.

ALL blasts were incubated with a monoclonal antibody anti-human CD10-APC (eBioscience, Thermo Fisher Scientific Cat# 17-0106-42, RRID:AB_11043552) for 30 minutes at 4°C; then cells were washed with cold PBS and stained using the GFP-Certified Apoptosis/Necrosis Detection Kit (Enzo Life Science Inc. Cat#ENZ-51002). After 15 minutes at RT in the dark, cells were analyzed using the FACS Canto II flow cytometer (BD Bioscience) with FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences).

Gene silencing

For GS silencing, either mesenchymal cells or RS4;11 cells were transfected with scramble (ON-TARGETplus Non-targeting Pool), GLUL- (ON-TARGETplus Human GLUL siRNA-SMARTpool). For MSCs DharmaFECT (Dharmacon) transfection reagent was used, while for RS4;11 a Nucleofector Kit was used (Lonza, Cat#LOVAPE1001).

For SNAT5 silencing, mesenchymal stromal cells were incubated with HiPerFect transfection reagent (Qiagen) in the presence of scramble or SLC38A5-targeting siRNAs (ON-TARGETplus Human SLC38A5 siRNA-SMARTpool). All procedures were made according to manufacturer’s instructions. The ability of MSCs to differentiate into osteoblasts and adipocytes were affected by neither transfection nor gene silencing (supplemental Figure 2). For detailed procedures, see supplemental Material and Methods.

Exchange rates of Gln and Asn

RS4;11 cells were seeded at 5·105 cells/mL in DMEM, supplemented with 400 μM Asn and 10% dialyzed FBS in the absence or in the presence of Gln (2 mM). After 48 hours, cell number was determined, and supernatants were used for Gln determination with liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry, as previously described.22

To evaluate the exchange rates of Gln and Asn in mesenchymal cells under physiological conditions, cells were seeded at 104 cells/cm2 in Plasmax, an advanced medium reproducing the composition of human plasma,23 containing 0.65 mM of 13C5 Glutamine (13C5, 99%, Cambridge Isotopes Laboratories), supplemented with 10% dialyzed FBS, in the absence or in the presence of a physiological concentration of Asn (41 μM). After 48 hours, samples were prepared for liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry analysis, as previously described.24 For detailed procedures see supplemental Materials and Methods.

MSC differentiation potential, Viability assay, Gene Silencing, RT-PCR, Western Blot, Immunofluorescence and Confocal Microscopy, Intracellular amino acids, Gln secretion by RS4;11 cells, Amino acid efflux from MSCs, Exchange rates of Gln and Asn.

See supplemental Materials and Methods.

Statistics

For statistical analysis, one-tailed Student t test for unpaired samples was used unless otherwise specified. Prism 6.0 (GraphPad Software Inc) was used for statistical analyses, and P values < .05 were considered statistically significant. Data were expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD) of at least 3 biological independent experiments with no less than 3 technical replicates each. The number of individual mesenchymal cell strains used and statistical details are given in the figure legends. Distinct subcultures, at different passages in vitro or from subcultures thawed at different times, have been used when a cell strain from a single donor has been used in independent experiments. Whenever possible, in each panel a different symbol has been used to distinguish data obtained from MSCs of individual donors.

Results

MSCs from ALL patients protect l-asparaginase-treated leukemia blasts better than MSCs from healthy donors

In the representative experiment shown in Figure 1A, the percentage of RS4;11 ALL cells killed by l-asparaginase (1U/mL) decreased from 36% to 20% when cocultured with mesenchymal cells from healthy donors (HD-MSCs) but dropped to 12% when cocultured with mesenchymal cells derived from ALL patients (ALL-MSCs). Comparing ALL-MSCs from 3 different ALL patients with HD-MSCs from 3 different, unrelated healthy donors, the protection index (see Materials and Methods) was 1.7 for ALL-MSCs and <1 for HD-MSCs (Figure 1B). In both cases, the protective effect was significantly reduced at comparable levels by the irreversible GS inhibitor methionine-l-sulfoximine. Consistent results were obtained on primary blasts from ALL patients treated with l-asparaginase or l-asparaginase + methionine-l-sulfoximine in monoculture or in coculture with mesenchymal cells derived from healthy donors or unrelated ALL patients. As shown in Figure 1C, compared with HD-MSC, ALL-MSCs exerted a higher protection, almost abolished by methionine-l-sulfoximine in both types of stromal cells.

MSCs from ALL patients (ALL-MSCs) protect l-asparaginase-treated leukemia blasts better than MSCs from healthy donors (HD-MSCs). (A) MSCs from an ALL patient (UPN #14, supplemental Table 2A) or from a healthy donor (UPN #11, supplemental Table 2B) were cocultured for 48 hours with RS4;11 ALL cells in the presence of l-asparaginase (ASNase, 1 U/ml) or l-asparaginase + methionine-l-sulfoximine (ASNase + MSO, 1 mM). The percentages of dead RS4;11 cells, obtained in a representative experiment, are shown. (B) The protection index was calculated on RS4;11 cells treated for 48 hours with ASNase or ASNase + MSO in the presence of ALL- or HD-MSCs derived from 3 distinct patients (UPN#14-15-16, supplemental Table 2A) or healthy donors (UPN#11-14-16, supplemental Table 2B). (C) The protection index was calculated on primary blasts treated for 48 hours with ASNase or ASNase + MSO in the presence of unrelated ALL- or HD-MSCs. For panels B and C, means ± SD of 3 (B) or 5 (C) independent experiments performed with MSCs from 3 (B) or 2 (C) different patients (UPN#11-12, supplemental Table 2A) or healthy donors (UPN#1-3, supplemental Table 2B) were used. For panel C, blasts from 3 different, unrelated ALL patients (UPN#4-5-6, supplemental Table 2A) were used. UPN#4-5 have been cocultured with UPN#11-12 (supplemental Table 2A) and UPN#1-3 (supplemental Table 2B), and UPN#6 has been cocultured with UPN#11 (supplemental Table 2A) and UPN#1 (supplemental Table 2B). For the calculation of the protection index, see Materials and Methods. *P < .05 (one-tailed Student t test for paired samples). For panels B and C, in each panel different symbol identifies MSCs from an individual donor.

MSCs from ALL patients (ALL-MSCs) protect l-asparaginase-treated leukemia blasts better than MSCs from healthy donors (HD-MSCs). (A) MSCs from an ALL patient (UPN #14, supplemental Table 2A) or from a healthy donor (UPN #11, supplemental Table 2B) were cocultured for 48 hours with RS4;11 ALL cells in the presence of l-asparaginase (ASNase, 1 U/ml) or l-asparaginase + methionine-l-sulfoximine (ASNase + MSO, 1 mM). The percentages of dead RS4;11 cells, obtained in a representative experiment, are shown. (B) The protection index was calculated on RS4;11 cells treated for 48 hours with ASNase or ASNase + MSO in the presence of ALL- or HD-MSCs derived from 3 distinct patients (UPN#14-15-16, supplemental Table 2A) or healthy donors (UPN#11-14-16, supplemental Table 2B). (C) The protection index was calculated on primary blasts treated for 48 hours with ASNase or ASNase + MSO in the presence of unrelated ALL- or HD-MSCs. For panels B and C, means ± SD of 3 (B) or 5 (C) independent experiments performed with MSCs from 3 (B) or 2 (C) different patients (UPN#11-12, supplemental Table 2A) or healthy donors (UPN#1-3, supplemental Table 2B) were used. For panel C, blasts from 3 different, unrelated ALL patients (UPN#4-5-6, supplemental Table 2A) were used. UPN#4-5 have been cocultured with UPN#11-12 (supplemental Table 2A) and UPN#1-3 (supplemental Table 2B), and UPN#6 has been cocultured with UPN#11 (supplemental Table 2A) and UPN#1 (supplemental Table 2B). For the calculation of the protection index, see Materials and Methods. *P < .05 (one-tailed Student t test for paired samples). For panels B and C, in each panel different symbol identifies MSCs from an individual donor.

Optimal protective effect requires Glutamine Synthetase activity in both mesenchymal and leukemia cells

To understand the mechanism underlying the inhibition by methionine-l-sulfoximine, we evaluated the effect of the GS inhibitor during l-asparaginase treatment of mesenchymal and leukemia cells in monocultures or in coculture.

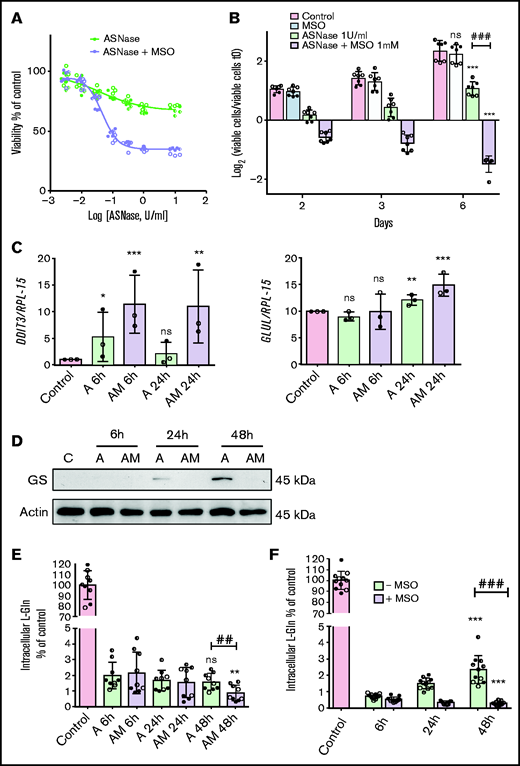

In the absence of the GS inhibitor, MSCs from ALL patients showed a modest and transient decrease in cell viability upon l-asparaginase treatment (Figure 2A-B). Conversely, in the presence of methionine-l-sulfoximine, l-asparaginase produced a marked and sustained viability decrease and, at later times, cell death (Figure 2A-B). In the absence of asparaginase, the GS inhibitor did not lower cell viability. In cells treated with asparaginase alone, the gene DDIT3, for the pro-apoptotic protein CHOP, was only transiently induced but stably upregulated if methionine-l-sulfoximine was also present (Figure 2C).

ALL-MSCs adapt to l-asparaginase through increased Glutamine Synthetase activity. (A) ALL-MSCs were incubated for 48 hours with the indicated doses of l-asparaginase (ASNase) in the absence or in the presence of methionine-l-sulfoximine (MSO, 1 mM), and viability was assessed with the resazurin method. Data are means ± SD of 9 independent experiments performed on MSCs derived from 3 distinct patients (UPN#12-15-16, supplemental Table 2A). Nonlinear regression analysis was used to obtain dose response curves. (B) ALL-MSCs were incubated in the absence (Control) or in the presence of ASNase (1 U/ml), MSO (1 mM), or ASNase + MSO, and cell growth was evaluated at the indicated times. Data are expressed as Log2 of the ratio between viable cells at the experimental time and viable cells at time 0 and are means ± SD of 7 independent experiments performed with cells from 3 ALL patients (UPN#14-15-16, supplemental Table 2A). *** P < .001 vs control cells at 6d; ### P < .001 cells treated with ASNase vs cells treated with ASNase + MSO. (C-E) ALL-MSCs were incubated for the indicated times in normal growth medium (Control) or in the presence of ASNase (A) or ASNase + MSO (AM) and then extracted for mRNA (C), protein (D), or amino acid (E) analysis. (C) The relative expression of DDIT3 and GLUL was determined, normalizing data for RPL-15 mRNA and expressing the results as folds of the mean value obtained in control cells, kept at 1. Data are means ± SD of 3 independent experiments performed with MSCs from 3 different patients (UPN#14-15-16, supplemental Table 2A). *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001 vs control cells. (D) A representative western blot of GS is shown. Actin was used for loading control. The experiment was performed with ALL-MSCs from 4 different patients (UPN#11-12-13-16, supplemental Table 2A) with comparable results. (E) The intracellular content of Gln was determined at the indicated experimental times. Data are means ± SD of 9 independent experiments performed with MSCs from 3 different patients (UPN#12-14-15, supplemental Table 2A). **P < .01 vs cells undergoing the same treatment of 6 hours, ## P < .01 cells treated with l-asparaginase vs cells treated with ASNase + MSO for 48 hours. (F) ALL-MSCs were incubated for 48 hours in a Gln- and Asn-free medium in the absence or in the presence of MSO (1 mM) or in normal growth medium (Control). At the indicated times, intracellular Gln was determined. Data are means ± SD of 11 independent experiments performed with MSCs from 4 patients (UPN#11-12-13-16, supplemental Table 2A). ***P < .001 vs cells undergoing the same treatment of 6 hours; ###P < .001, cells incubated in the absence of MSO vs cells incubated in the presence of MSO for 48 hours. For panels A, B, C, E, and F, in each panel different symbol identifies MSCs from an individual donor.

ALL-MSCs adapt to l-asparaginase through increased Glutamine Synthetase activity. (A) ALL-MSCs were incubated for 48 hours with the indicated doses of l-asparaginase (ASNase) in the absence or in the presence of methionine-l-sulfoximine (MSO, 1 mM), and viability was assessed with the resazurin method. Data are means ± SD of 9 independent experiments performed on MSCs derived from 3 distinct patients (UPN#12-15-16, supplemental Table 2A). Nonlinear regression analysis was used to obtain dose response curves. (B) ALL-MSCs were incubated in the absence (Control) or in the presence of ASNase (1 U/ml), MSO (1 mM), or ASNase + MSO, and cell growth was evaluated at the indicated times. Data are expressed as Log2 of the ratio between viable cells at the experimental time and viable cells at time 0 and are means ± SD of 7 independent experiments performed with cells from 3 ALL patients (UPN#14-15-16, supplemental Table 2A). *** P < .001 vs control cells at 6d; ### P < .001 cells treated with ASNase vs cells treated with ASNase + MSO. (C-E) ALL-MSCs were incubated for the indicated times in normal growth medium (Control) or in the presence of ASNase (A) or ASNase + MSO (AM) and then extracted for mRNA (C), protein (D), or amino acid (E) analysis. (C) The relative expression of DDIT3 and GLUL was determined, normalizing data for RPL-15 mRNA and expressing the results as folds of the mean value obtained in control cells, kept at 1. Data are means ± SD of 3 independent experiments performed with MSCs from 3 different patients (UPN#14-15-16, supplemental Table 2A). *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001 vs control cells. (D) A representative western blot of GS is shown. Actin was used for loading control. The experiment was performed with ALL-MSCs from 4 different patients (UPN#11-12-13-16, supplemental Table 2A) with comparable results. (E) The intracellular content of Gln was determined at the indicated experimental times. Data are means ± SD of 9 independent experiments performed with MSCs from 3 different patients (UPN#12-14-15, supplemental Table 2A). **P < .01 vs cells undergoing the same treatment of 6 hours, ## P < .01 cells treated with l-asparaginase vs cells treated with ASNase + MSO for 48 hours. (F) ALL-MSCs were incubated for 48 hours in a Gln- and Asn-free medium in the absence or in the presence of MSO (1 mM) or in normal growth medium (Control). At the indicated times, intracellular Gln was determined. Data are means ± SD of 11 independent experiments performed with MSCs from 4 patients (UPN#11-12-13-16, supplemental Table 2A). ***P < .001 vs cells undergoing the same treatment of 6 hours; ###P < .001, cells incubated in the absence of MSO vs cells incubated in the presence of MSO for 48 hours. For panels A, B, C, E, and F, in each panel different symbol identifies MSCs from an individual donor.

The expression of GLUL mRNA, which codes for GS, was not changed substantially by l-asparaginase (Figure 2C), but the levels of GS protein, which was not detectable under control conditions, became sizable at 24 hours of incubation and dramatically increased at 48 hours in the absence but not in the presence of methionine-l-sulfoximine (Figure 2D). Also, MSCs from healthy donors exhibited a successful, methionine-l-sulfoximine -inhibitable, adaptation to l-asparaginase and markedly increased the expression of GS from 24 hours of treatment (supplemental Figure 3A-B).

In contrast to GS, asparagine synthetase (ASNS) was induced at messenger RNA(mRNA), but not at protein level in ALL-MSCs, both in the absence and in the presence of methionine-l-sulfoximine (supplemental Figure 4A-B).

This different behavior of GS and ASNS was consistent with Gln and Asn levels in ALL-MSCs during l-asparaginase treatment. In the first 6 hours of incubation, both cell Gln (Figure 2E) and Asn (supplemental Figure 4C) drastically decreased. Afterward, cell Gln was maintained stable in the absence of methionine-l-sulfoximine but further decreased in the presence of the inhibitor (Figure 2E), a clear-cut demonstration of GS activity in l-asparaginase-treated ALL-MSCs. Comparable results were obtained in mesenchymal cells derived from healthy donors (supplemental Figure 3C). Instead, cell Asn progressively decreased up to 48 hours of treatment, without any significant difference between cells incubated in the absence or in the presence of methionine-l-sulfoximine (supplemental Figure 4C). Moreover, when MSCs were incubated in media deprived of Gln and Asn, a less drastic condition than l-asparaginase treatment, they partially rescued cell Gln in the absence but not in the presence of methionine-l-sulfoximine (Figure 2F), while no significant decrease in cell Asn was detected, either in the absence or in the presence of the inhibitor (supplemental Figure 4D).

These results indicate that increased expression and activity of GS play a major role in the successful adaptation of mesenchymal cells to l-asparaginase, while the contribution of ASNS does not appear substantial.

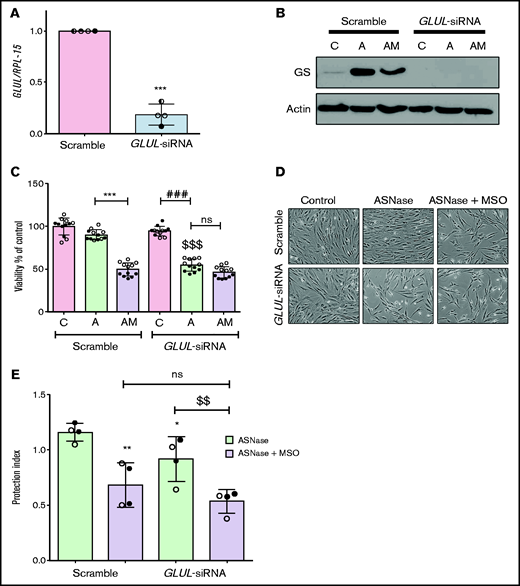

To exclude off-target effects of methionine-l-sulfoximine, GLUL was silenced in ALL-MSCs (Figure 3A). Upon l-asparaginase treatment, GLUL silencing prevented the increased expression of GS (Figure 3B) and halved cell viability, hampering the adaptation, with no further decrease upon the addition of methionine-l-sulfoximine (Figure 3C-D). When GLUL-silenced ALL-MSCs were cocultured with RS4;11 cells and treated with l-asparaginase in the absence of methionine-l-sulfoximine, a small but significant reduction of the protective effect was observed compared with the scramble-transfected mesenchymal cells. However, in the presence of methionine-l-sulfoximine, the protection index was much lower, independently of the GS status in the MSCs used for the coculture (Figure 3E). Interestingly, when RS4;11 cells were treated with l-asparaginase in monoculture, the basal expression of GS was significantly increased (supplemental Figure 5A), and cell Gln was lower in the presence of methionine-l-sulfoximine than in its absence (supplemental Figure 5B); however, methionine-l-sulfoximine had no significant effect on death of l-asparaginase-treated RS4;11 cells (supplemental Figure 5C).

Glutamine Synthetase activity is required in both MSCs and leukemia cells for optimal protection from l-asparaginase. (A) ALL-MSCs were transfected with scramble (kept at 1) or GLUL-siRNA (see Materials and Methods), and the expression of GLUL mRNA was evaluated after 48 hours. Means ± SD of 4 independent experiments performed with MSCs from 4 patients (UPN#12-14-15-16, supplemental Table 2A) are shown. ***P < .001. (B-D) Scramble-transfected or GLUL-silenced ALL-MSCs were treated for 72 hours with l-asparaginase (lane A) or with l-asparaginase + methionine-l-sulfoximine (lane AM). (B) Expression of GS protein. A representative experiment is shown with actin used for loading control. (C) Cell viability. Data are expressed as percentage of the viability of untreated scramble-transfected cells and are means ± SD of 12 independent experiments performed with MSCs from 2 patients (UPN#14-15, supplemental Table 2A). ***P < .001, scramble transfected cells treated with l-asparaginase vs scramble transfected cells treated with l-asparaginase + methionine-l-sulfoximine; ###P < .001 l-asparaginase-treated GLUL-silenced cells vs control GLUL-silenced cells; $$$P < .001 vs l-asparaginase-treated scramble transfected cells. (D) Representative images of cell cultures treated as in panel C (bar = 100 μm). (E) RS4;11 cells were treated for 48 hours with l-asparaginase (ASNase,1 U/ml) in monoculture or in direct contact with scramble-transfected or GLUL-silenced MSCs in the absence or in the presence of methionine-l-sulfoximine (MSO), and the protection index was calculated. Data are means ± SD of 4 independent experiments performed with MSCs from 2 different patients (UPN#12-16, supplemental Table 2A). *P < .05, **P < .01 vs scramble-transfected cells treated with ASNase alone; $$P < .01 GLUL-silenced cells treated with ASNase alone vs GLUL-silenced cells treated with ASNase + MSO. For panels A, C, and E, in each panel different symbol identifies MSCs from an individual donor.

Glutamine Synthetase activity is required in both MSCs and leukemia cells for optimal protection from l-asparaginase. (A) ALL-MSCs were transfected with scramble (kept at 1) or GLUL-siRNA (see Materials and Methods), and the expression of GLUL mRNA was evaluated after 48 hours. Means ± SD of 4 independent experiments performed with MSCs from 4 patients (UPN#12-14-15-16, supplemental Table 2A) are shown. ***P < .001. (B-D) Scramble-transfected or GLUL-silenced ALL-MSCs were treated for 72 hours with l-asparaginase (lane A) or with l-asparaginase + methionine-l-sulfoximine (lane AM). (B) Expression of GS protein. A representative experiment is shown with actin used for loading control. (C) Cell viability. Data are expressed as percentage of the viability of untreated scramble-transfected cells and are means ± SD of 12 independent experiments performed with MSCs from 2 patients (UPN#14-15, supplemental Table 2A). ***P < .001, scramble transfected cells treated with l-asparaginase vs scramble transfected cells treated with l-asparaginase + methionine-l-sulfoximine; ###P < .001 l-asparaginase-treated GLUL-silenced cells vs control GLUL-silenced cells; $$$P < .001 vs l-asparaginase-treated scramble transfected cells. (D) Representative images of cell cultures treated as in panel C (bar = 100 μm). (E) RS4;11 cells were treated for 48 hours with l-asparaginase (ASNase,1 U/ml) in monoculture or in direct contact with scramble-transfected or GLUL-silenced MSCs in the absence or in the presence of methionine-l-sulfoximine (MSO), and the protection index was calculated. Data are means ± SD of 4 independent experiments performed with MSCs from 2 different patients (UPN#12-16, supplemental Table 2A). *P < .05, **P < .01 vs scramble-transfected cells treated with ASNase alone; $$P < .01 GLUL-silenced cells treated with ASNase alone vs GLUL-silenced cells treated with ASNase + MSO. For panels A, C, and E, in each panel different symbol identifies MSCs from an individual donor.

These results indicate that GS inhibition significantly hampers leukemic cell survival only when mesenchymal and leukemic cells are cocultured, suggesting that optimal protection requires GS activity in both stromal cells and ALL blasts.

MSCs secrete Asn synthesized exploiting glutamine produced by leukemia cells

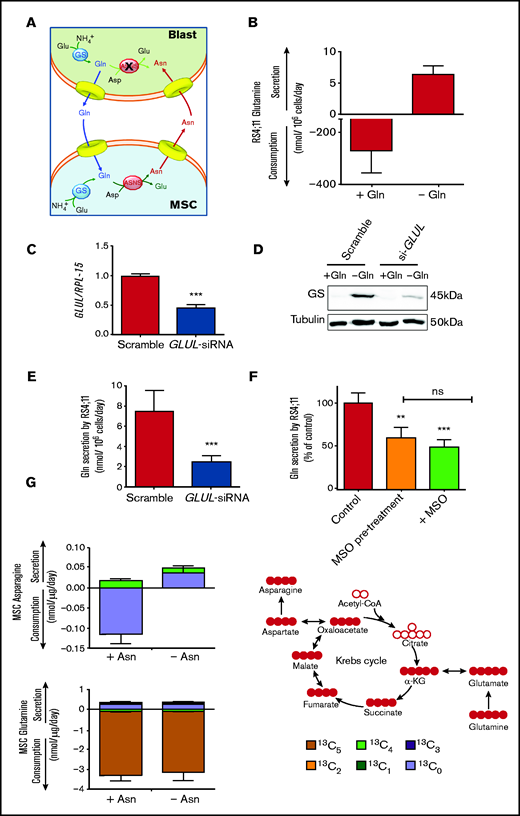

To explain the role of GS in the protective effect, a matched amino acid exchange between leukemia blasts and mesenchymal cells is proposed (Figure 4A). According to this working model, ALL blasts synthesize and extrude Gln, which is used by MSCs for the synthesis of Asn that, in turn, is exported to support ASNS-negative blasts.

Leukemia cells release neo-synthetized Gln and MSCs use the amino acid to synthetize and secrete Asn. (A) A working model of the amino acid trade-off between ALL blasts and MSCs in the bone marrow niche is shown. Upon l-asparaginase treatment, asparagine (Asn) and glutamine (Gln) are hydrolyzed in the bulk phase, promoting GS expression in MSCs and ALL blasts. Asparagine Synthetase (ASNS)-negative ALL blasts synthetize Gln that is provided to MSCs for the synthesis of Asn, which is then extruded to supply ALL blasts, allowing their survival. (B) RS4;11 cells were incubated for 48 hours in the absence or presence of Gln (2 mM), and the exchange rate of Gln was evaluated. Data are means ± SD of 6 independent experiments. (C) RS4;11 cells were transfected with scramble or GLUL-siRNA (see Materials and Methods), and the expression of GLUL mRNA was evaluated after 24 hours. ***P < .001. (D) Expression of GS protein was evaluated in scramble-transfected or GLUL-silenced RS4;11 cells after 48 hours of incubation in the absence or in the presence of Gln (2 mM). Tubulin was used for loading control. A representative experiment is shown. (E) Scramble-transfected or GLUL-silenced RS4;11 cells were incubated for 48 hours in the absence of Gln, and Gln secretion was evaluated. Data are means ± SD of 6 independent experiments. ***P < .001 (F) After a 24-hour incubation in standard growth medium in the presence or in the absence of 1 mM methionine-l-sulfoximine (MSO), RS4;11 cells were incubated in the absence of Gln for further 24 hours. During this period, cells preincubated in the absence of MSO were maintained without the inhibitor (Control), while cells preincubated in the presence of MSO were maintained with the inhibitor (+MSO) or incubated in the absence of the inhibitor (MSO pretreatment). Data are expressed as % of Gln secretion in Control cells and are means ± SD of 4 independent experiments. **P < .01; ***P < .001 vs Control. (G) Exchange rates of Asn and Gln in 13C5-Gln-labeled ALL-MSCs incubated for 48 hours in Plasmax medium (Gln = 0.6 mM) in the absence or presence of Asn (41 μM) were determined. Data are means ± SD of 4 independent experiments with MSCs from 4 different patients (UPN#6-17-18-19, supplemental Table 2A). On the right, a schematic representation of labeling of intracellular metabolites upon incubation with 13C-Gln is shown.

Leukemia cells release neo-synthetized Gln and MSCs use the amino acid to synthetize and secrete Asn. (A) A working model of the amino acid trade-off between ALL blasts and MSCs in the bone marrow niche is shown. Upon l-asparaginase treatment, asparagine (Asn) and glutamine (Gln) are hydrolyzed in the bulk phase, promoting GS expression in MSCs and ALL blasts. Asparagine Synthetase (ASNS)-negative ALL blasts synthetize Gln that is provided to MSCs for the synthesis of Asn, which is then extruded to supply ALL blasts, allowing their survival. (B) RS4;11 cells were incubated for 48 hours in the absence or presence of Gln (2 mM), and the exchange rate of Gln was evaluated. Data are means ± SD of 6 independent experiments. (C) RS4;11 cells were transfected with scramble or GLUL-siRNA (see Materials and Methods), and the expression of GLUL mRNA was evaluated after 24 hours. ***P < .001. (D) Expression of GS protein was evaluated in scramble-transfected or GLUL-silenced RS4;11 cells after 48 hours of incubation in the absence or in the presence of Gln (2 mM). Tubulin was used for loading control. A representative experiment is shown. (E) Scramble-transfected or GLUL-silenced RS4;11 cells were incubated for 48 hours in the absence of Gln, and Gln secretion was evaluated. Data are means ± SD of 6 independent experiments. ***P < .001 (F) After a 24-hour incubation in standard growth medium in the presence or in the absence of 1 mM methionine-l-sulfoximine (MSO), RS4;11 cells were incubated in the absence of Gln for further 24 hours. During this period, cells preincubated in the absence of MSO were maintained without the inhibitor (Control), while cells preincubated in the presence of MSO were maintained with the inhibitor (+MSO) or incubated in the absence of the inhibitor (MSO pretreatment). Data are expressed as % of Gln secretion in Control cells and are means ± SD of 4 independent experiments. **P < .01; ***P < .001 vs Control. (G) Exchange rates of Asn and Gln in 13C5-Gln-labeled ALL-MSCs incubated for 48 hours in Plasmax medium (Gln = 0.6 mM) in the absence or presence of Asn (41 μM) were determined. Data are means ± SD of 4 independent experiments with MSCs from 4 different patients (UPN#6-17-18-19, supplemental Table 2A). On the right, a schematic representation of labeling of intracellular metabolites upon incubation with 13C-Gln is shown.

In line with the model, ALL cells express GS, and the levels of the enzyme were progressively increased if Gln concentration in the medium was decreased and Asn was present (supplemental Figure 6A-B). GS activity in leukemic cells was further documented by a sizable secretion of Gln (Figure 4B) that was markedly reduced by either GS-silencing (Figure 4C-E) or inhibition by methionine-l-sulfoximine (Figure 4F).

To validate the role played by mesenchymal cells in the model, Asn and Gln exchange rates by ALL-MSCs were investigated under conditions mimicking bone marrow in vivo (Figure 4G). MSCs were cultured in Plasmax, a medium recapitulating the normal levels of nutrients found in human plasma,23,24 supplemented with 13C5 Gln. The experiment was performed comparing cells incubated in normal Plasmax (Asn = 41 μM) with MSCs cultured in Asn-free Plasmax (see supplemental Materials for details), which mimics the Asn-depleted environment imposed by l-asparaginase treatment in the bone marrow.25 In the presence of Asn, stromal cells showed a net uptake of both Asn and Gln, while, when Asn was removed, a net release of Asn was observed and, moreover, at least a quarter of the released amino acid was derived from the oxidative metabolism of glutamine taken up from the medium (13C4 Asn). Thus, mesenchymal cells use extracellular Gln to synthesize Asn that is then secreted.

Increased expression and activity of the SNAT5 transporter in MSCs is associated with enhanced protection

Having demonstrated that ALL-MSCs are able to secrete Asn, we have hypothesized that faster Asn efflux may underlie their larger protective ability compared with cells from healthy donors. To verify this possibility, we preloaded mesenchymal cells derived from ALL patients and healthy donors with Asn and evaluated the efflux of the amino acid into Asn-free medium, demonstrating that ALL-MSCs exhibited a significantly faster Asn efflux than HD-MSCs (Figure 5A).

ALL-MSCs express higher levels of SNAT5 transporter and secrete more Asn than HD-MSCs. (A) Fractional Asn efflux (Equation 3, supplemental Materials and Methods) was determined in ALL-MSCs and HD-MSCs. Data are means ± SD of 15 independent experiments performed with MSCs from 3 different patients (UPN#12-13-16, supplemental Table 2A) or healthy donors (UPN#9-10-11, supplemental Table 2B). *P < .05. (B) The expression of the indicated genes was determined in a panel of ALL-MSCs and HD-MSCs. Data are expressed as fold-change, normalizing against the average expression of healthy donors and are means ± SD of 6 independent experiments performed with MSCs from 6 different patients (UPN#11-12-13-14-15-16, supplemental Table 2A) or healthy donors (UPN#9-10-11-12-13-14, supplemental Table 2B). *P < .05; **P < .01 (C) Western blot of SNAT5 expression in 2 panels of MSCs obtained from 4 distinct ALL patients (UPN#11-14-15-16, supplemental Table 2A) or healthy donors (UPN#10-11-12-13, supplemental Table 2B) (top). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used for loading control. Densitometric analysis of SNAT5 expression, normalized for GAPDH (bottom). Means ± SD are shown. *P < .05. (D) The mean intensity of SNAT5 signal was detected in ALL-MSCs derived from 3 different patients (UPN#11-12-14, supplemental Table 2A), and HD-MSCs derived from 3 different donors (UPN#9-11-13, supplemental Table 2B). Data are expressed as the ratio between mean intensity and the number of cells in the same fields (81 in 10 fields for ALL-MSCs and 93 in 19 fields for HD-MSCs) ***P < .001. For all the panels, Mann-Whitney U test was used. For panels A, B, C, and D, in each panel different symbol identifies MSCs from an individual donor.

ALL-MSCs express higher levels of SNAT5 transporter and secrete more Asn than HD-MSCs. (A) Fractional Asn efflux (Equation 3, supplemental Materials and Methods) was determined in ALL-MSCs and HD-MSCs. Data are means ± SD of 15 independent experiments performed with MSCs from 3 different patients (UPN#12-13-16, supplemental Table 2A) or healthy donors (UPN#9-10-11, supplemental Table 2B). *P < .05. (B) The expression of the indicated genes was determined in a panel of ALL-MSCs and HD-MSCs. Data are expressed as fold-change, normalizing against the average expression of healthy donors and are means ± SD of 6 independent experiments performed with MSCs from 6 different patients (UPN#11-12-13-14-15-16, supplemental Table 2A) or healthy donors (UPN#9-10-11-12-13-14, supplemental Table 2B). *P < .05; **P < .01 (C) Western blot of SNAT5 expression in 2 panels of MSCs obtained from 4 distinct ALL patients (UPN#11-14-15-16, supplemental Table 2A) or healthy donors (UPN#10-11-12-13, supplemental Table 2B) (top). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used for loading control. Densitometric analysis of SNAT5 expression, normalized for GAPDH (bottom). Means ± SD are shown. *P < .05. (D) The mean intensity of SNAT5 signal was detected in ALL-MSCs derived from 3 different patients (UPN#11-12-14, supplemental Table 2A), and HD-MSCs derived from 3 different donors (UPN#9-11-13, supplemental Table 2B). Data are expressed as the ratio between mean intensity and the number of cells in the same fields (81 in 10 fields for ALL-MSCs and 93 in 19 fields for HD-MSCs) ***P < .001. For all the panels, Mann-Whitney U test was used. For panels A, B, C, and D, in each panel different symbol identifies MSCs from an individual donor.

Asn secretion implies the activity of amino acid transporters and, therefore, we compared the expression of several transporters (SLC38A1, SLC38A2, SLC38A3, SLC38A5 and SLC1A5) potentially involved in Asn efflux in a panel of MSCs derived from ALL patients or healthy donors (Figure 5B). The expression of SLC1A5 (for ASCT2), SLC38A2 (for SNAT2) and SLC38A3 (for SNAT3) did not exhibit significant changes. A significant change was detected for SLC38A1 (for SNAT1), but the most striking change concerned SLC38A5 (for SNAT5), which was approximately threefold more expressed in ALL-MSCs than in HD-MSCs. The differential expression of SNAT5 was confirmed at the protein level with a western blot analysis (Figure 5C), which indicated a threefold higher expression of the transporter in ALL-MSCs. Immunofluorescence staining also showed a more evident membrane localization of the transporter in stromal cells derived from ALL patients than in HD-MSCs (Figure 5D; supplemental Figure 7). Incidentally, the expression of both ASNS and GLUL was similar in the same panels of mesenchymal cells (supplemental Figure 8).

SNAT5 mediates the bidirectional transport of Asn, Gln, and histidine (His), depending on their transmembrane gradients,6 and is therefore expected to operate Asn efflux under conditions of extracellular Asn deprivation. Thus, the increased expression of SNAT5 of ALL-MSCs may underlie their enhanced protective activity.

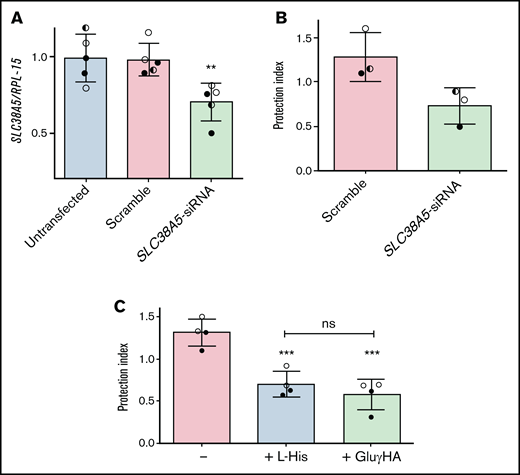

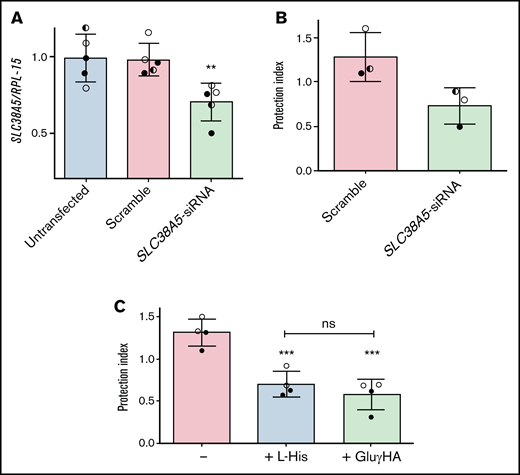

To corroborate this hypothesis, SLC38A5 was silenced in ALL-MSCs (Figure 6A), and the protective effect of knocked-down cells was assessed in l-asparaginase-treated cocultures with ALL cells (Figure 6B). The reduction of SLC38A5 expression was only partial, but enough to reduce by 40% the protective capacity of mesenchymal cells.

The inhibition of System N transporters lowers the protective effect by ALL-MSCs. (A,C) ALL-MSCs were transfected with scramble or SLC38A5-siRNA (see Materials and Methods). (A) The expression of SLC38A5 mRNA was evaluated after 4 ddays. Data are expressed as folds of the mean value obtained in untransfected MSCs, kept at 1, and are means ± SD of 5 independent experiments performed with ALL-MSCs derived from 3 distinct patients (UPN#6-7-16, supplemental Table 2A). **P < .01. (B) RS4;11 cells were treated with l-asparaginase in monoculture or coculture with scramble-transfected or SLC38A5-silenced ALL-MSCs, and the protection index was determined. Data are means ± SD of 3 independent experiments performed with ALL-MSCs derived from 3 distinct patients (UPN#6-7-16, supplemental Table 2A). *P < .05. (C) RS4;11 cells were treated with l-asparaginase in monoculture or coculture with ALL-MSCs in the absence or in the presence of L-Histidine (L-His, 10mM) or l-glutamic acid γ-monohydroxamate (GluγHA, 1mM). The protection index is shown in the 3 conditions. Data are means ± SD of 4 independent experiments performed with ALL-MSCs derived from 2 distinct patients (UPN#8-16, supplemental Table 2A). ***P < .001 vs the protection index obtained in the absence of inhibitors. For panels A, B, and C, in each panel different symbol identifies MSCs from an individual donor.

The inhibition of System N transporters lowers the protective effect by ALL-MSCs. (A,C) ALL-MSCs were transfected with scramble or SLC38A5-siRNA (see Materials and Methods). (A) The expression of SLC38A5 mRNA was evaluated after 4 ddays. Data are expressed as folds of the mean value obtained in untransfected MSCs, kept at 1, and are means ± SD of 5 independent experiments performed with ALL-MSCs derived from 3 distinct patients (UPN#6-7-16, supplemental Table 2A). **P < .01. (B) RS4;11 cells were treated with l-asparaginase in monoculture or coculture with scramble-transfected or SLC38A5-silenced ALL-MSCs, and the protection index was determined. Data are means ± SD of 3 independent experiments performed with ALL-MSCs derived from 3 distinct patients (UPN#6-7-16, supplemental Table 2A). *P < .05. (C) RS4;11 cells were treated with l-asparaginase in monoculture or coculture with ALL-MSCs in the absence or in the presence of L-Histidine (L-His, 10mM) or l-glutamic acid γ-monohydroxamate (GluγHA, 1mM). The protection index is shown in the 3 conditions. Data are means ± SD of 4 independent experiments performed with ALL-MSCs derived from 2 distinct patients (UPN#8-16, supplemental Table 2A). ***P < .001 vs the protection index obtained in the absence of inhibitors. For panels A, B, and C, in each panel different symbol identifies MSCs from an individual donor.

Consistently, either His (10 mM), a natural substrate of the transporter, or the amino acid analog l-glutamic acid γ-monohydroxyamate (1 mM), a well-known inhibitor of SNAT5,26-28 significantly reduced (-45%) the protection index of ALL-MSCs on l-asparaginase treated RS4;11 cells (Figure 6C). Neither l-glutamic acid γ-monohydroxamate nor His had any effect on RS4;11 viability in monocultures (supplemental Figure 9).

Leukemia blasts induce SLC38A5 in mesenchymal cells

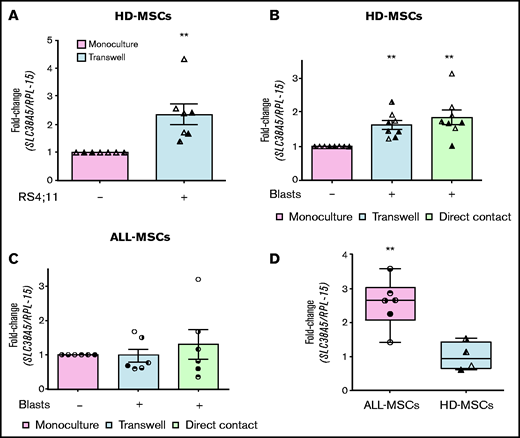

In the bone marrow of leukemia patients, mesenchymal cells are in direct contact with blasts. To test if cell-cell interaction modifies SLC38A5 expression in stromal cells, we cocultured MSCs derived from healthy donors with RS4;11 cells in a double chamber system, with HD-MSCs in the lower compartment. After 72 hours, the expression of SLC38A5 was significantly increased in cocultured stromal cells compared with cells in monoculture (Figure 7A). The significant induction of SLC38A5 was further confirmed by using primary ALL blasts (Figure 7B). Indeed, MSCs from 4 healthy donors and blasts from 3 ALL patients were cocultured either in a double chamber system or in direct contact and, in both systems, the expression of SLC38A5 was significantly increased in all MSCs cocultured with leukemic blasts independently of the strain used (8/8). Conversely, when ALL blasts were cocultured with MSCs derived from the same patient (Figure 7C), SLC38A5 was not significantly induced compared with the expression measured in monoculture. As expected from Figure 5B, the ALL-MSCs used in the experiment of Figure 7C are endowed with higher (P < .01) SLC38A5 expression than the HD-MSCs used in parallel (Figure 7D).

ALL blasts induce SLC38A5 in HD-MSCs. (A) HD-MSCs were cultured in the absence or in the presence of RS4;11 cells, and the expression of SLC38A5 was analyzed after 72 hours. (B) SLC38A5 expression was evaluated in HD-MSCs after coculture with unrelated ALL blasts. (C) SLC38A5 expression was evaluated in ALL-MSCs after coculture with related ALL blasts. (A-C) Data were normalized for RPL-15 mRNA abundance and reported as folds of the mean value obtained in monoculture. Data are means ± SD of 7 (A) or 8 (B) or 6 (C) independent experiments performed with MSCs from 3 (A, UPN#10-15-17, supplemental Table 2B) or 4 (B, UPN#5-6-7-8, supplemental Table 2B) healthy donors or 6 patients (C, UPN#6-7-8-9-10-18). For panels B and C, blasts from 3 (UPN#1-2-3, supplemental Table 2A) or 6 (UPN#6-7-8-9-10-18) patients were used, respectively. **P < .01 (one-sample Student t test). (D) The expression of SLC38A5 was determined in the MSCs used for experiments shown in panels B and C. Data are expressed as fold-change, normalizing against the average expression of healthy donors and are means ± SD. **P < .01 (Mann-Whitney U test). For panels A, B, C, and D, in each panel different symbol identifies MSCs from an individual donor.

ALL blasts induce SLC38A5 in HD-MSCs. (A) HD-MSCs were cultured in the absence or in the presence of RS4;11 cells, and the expression of SLC38A5 was analyzed after 72 hours. (B) SLC38A5 expression was evaluated in HD-MSCs after coculture with unrelated ALL blasts. (C) SLC38A5 expression was evaluated in ALL-MSCs after coculture with related ALL blasts. (A-C) Data were normalized for RPL-15 mRNA abundance and reported as folds of the mean value obtained in monoculture. Data are means ± SD of 7 (A) or 8 (B) or 6 (C) independent experiments performed with MSCs from 3 (A, UPN#10-15-17, supplemental Table 2B) or 4 (B, UPN#5-6-7-8, supplemental Table 2B) healthy donors or 6 patients (C, UPN#6-7-8-9-10-18). For panels B and C, blasts from 3 (UPN#1-2-3, supplemental Table 2A) or 6 (UPN#6-7-8-9-10-18) patients were used, respectively. **P < .01 (one-sample Student t test). (D) The expression of SLC38A5 was determined in the MSCs used for experiments shown in panels B and C. Data are expressed as fold-change, normalizing against the average expression of healthy donors and are means ± SD. **P < .01 (Mann-Whitney U test). For panels A, B, C, and D, in each panel different symbol identifies MSCs from an individual donor.

Discussion

Mesenchymal cells are known to protect ALL blasts from a variety of stress conditions through several mechanisms, such as the induction of hERG potassium channel expression on the blast membrane,29 the activation of the Notch30 or Wnt31 pathways, the downregulation of p21,32 and the secretion of prostaglandin E2,33 VEGFA,34 cysteine,35 or asparagine.15 Among these, nutritional mechanisms are of particular importance, given the asparagine auxotrophy of leukemic blasts that lack ASNS, and become critical when asparagine and glutamine are depleted by l-asparaginase treatment. This contribution demonstrates that MSCs isolated from ALL patients protect leukemic blasts from l-asparaginase better than MSCs from healthy donors, and that optimal nutritional support requires a bidirectional amino acid trade-off between stromal cells and blasts that requires GS activity in either mesenchymal or leukemic cells.

In MSCs, increased GS activity is required for the adaptation to l-asparaginase, as demonstrated by the marked cytotoxicity observed if GS was silenced or inhibited during the incubation with the drug. As other cell types,36,37 mesenchymal cells exhibit a dramatic drop in intracellular Gln and Asn levels upon incubation with l-asparaginase, which triggers a nutritional stress, causing a proliferative arrest and the induction of ASNS and DDIT3, which encodes for the proapoptotic protein CHOP. Both DDIT3 and ASNS are targets of ATF4, the transcription factor that promotes the cell response to nutritional stress.38 However, these changes are only transient since, after 3 days of treatment, MSCs adapt to the drug and resume proliferation. The proliferative rescue is associated with increased GS protein levels, likely achieved by decreased ubiquitin-dependent degradation,39 without substantial changes in the transcription of the coding gene GLUL. Indeed, GS half-life is inversely correlated with the intracellular Gln concentration via the thalidomide receptor Cereblon.39 Since methionine-l-sulfoximine is a structural analog of Gln, it is possible that also the inhibitor accelerates GS degradation, thus explaining the lack of GS induction in cells treated with asparaginase and the inhibitor.

GS expression also increases in l-asparaginase-treated ALL cells, but methionine-l-sulfoximine significantly decreases cell viability only when blasts are cocultured with mesenchymal cells, indicating that GS inhibition in leukemic cells prevents the protective effect by stromal cells. Under the same conditions, GS silencing in MSCs had only a small inhibitory effect on the protection of ALL blasts, although mesenchymal cell viability is heavily compromised (Figure 3C), suggesting that the toxic effect of GS inhibition on MSCs themselves plays a marginal role in the reduction of protective capacity of stromal cells. These results imply that MSCs-dependent protection of leukemic cells requires GS activity in ALL blasts. While ASNS expression and activity have been extensively studied in ALL, the role of GS in leukemic cells has never been investigated in detail. Here we show that upon Gln shortage ALL cells upregulate GS and increase the synthesis of Gln, which is then secreted in the extracellular compartment. We also show that MSCs use extracellular Gln to synthetize Asn. On the bases of these results, we propose that a bidirectional exchange of Gln and Asn occurs in the leukemic bone marrow niche (Figure 4), where ALL cells produce and secrete Gln that is used by stromal cells to synthesize Asn, which is then exported to sustain ASNS-negative malignant cells.

Using 2 panels of MSCs derived from HD-MSCs and ALL-MSCs, we have demonstrated that stromal cells isolated from leukemic bone marrows protect much better ALL blasts from l-asparaginase. These data indicate that the amino acid trade-off must be more efficient in ALL-MSCs. This different behavior cannot be attributed to GS or ASNS because the expression of the 2 enzymes is comparable in both MSC types (supplemental Figure 8) and, moreover, both cell types adapt to l-asparaginase through increased GS expression and activity (see Figure 2 and supplemental Figure 3). However, the prosurvival intercellular amino acid flux implies the activity of amino acid transporters. The repertoire of amino acid transporters in human MSCs has been only recently evaluated in stromal cells from healthy donors.40 Comparing the expression of several transporters for Asn and Gln in HD- and ALL-MSCs, we found that SLC38A5, the gene that encodes for the transporter SNAT5, is significantly more expressed in mesenchymal cells from ALL patients. Consistently, Asn efflux is significantly faster in ALL-MSCs than in HD-MSCs, suggesting that SNAT5 is the carrier exploited for Asn secretion by stromal cells.

SNAT5 is a member of “system N,” a group of transporters which couple substrate fluxes with a Na+ symport and a proton antiport. This transporter can mediate either the influx or the efflux of Gln and Asn, depending on the prevailing gradient of substrates.6 Consistent with a role for the transporter in the amino acid exchange in the leukemic niche, the protection of ALL blasts is hindered by SNAT5 silencing or pharmacological inhibition with natural (histidine) or synthetic (l-glutamic acid γ-monohydroxamate) substrates. Although ALL-MSCs and HD-MSCs have comparable morphology, immunophenotype, differentiation potential, and in vitro life-span at diagnosis,41 they differ under many other aspects,42,43 such as the higher secretion of Activin A,44 inflammatory cytokines,45 or BMP4.46 However, none of these changes seems involved in a more efficient protection from the metabolic stress imposed by l-asparaginase. At variance with mesenchymal cells from healthy donors, ALL-MSCs have interacted with the leukemic cells in the bone marrow of patients. To reproduce this interaction in vitro, we cocultured HD-MSCs with primary ALL blasts. Importantly, leukemia cells induced SLC38A5 in HD-MSCs, suggesting that leukemic blasts educate the metabolism of stromal cells through changes in gene expression so as to ensure an enhanced protective capacity. On the contrary, no SLC38A5 induction is observed upon coculture of leukemic blasts with ALL-MSCs. A possible explanation is that mesenchymal derived from ALL patients had been already exposed to leukemic blasts in vivo and retain higher levels of the transporter ex vivo than HD-MSCs (Figures 5B and 7D). If this is the case, a stable mechanism for gene expression regulation, such as an epigenetic change, may be involved. Interestingly, although this hypothesis awaits experimental validation, epigenetic modulation of MSC gene expression has been repeatedly described in hematological malignancies.47,48

Overall, this study demonstrates that, in the bone marrow niche of ALL patients, blasts and mesenchymal cells arrange an amino acid trade-off, which is stimulated during l-asparaginase treatment and promotes resistance of Asn-auxotroph leukemic blasts to the drug. While the protective function of asparagine15 and/or glutamine20 production and export by stromal cells has been already hypothesized, the active role of ALL blasts in this exchange was thus far ignored. GS (in both MSCs and ALL blasts) and the transporter SNAT5 (in MSCs) are major players in this mechanism and, hence, constitute potential therapeutic targets. Moreover, higher levels of SNAT5 in mesenchymal cells correspond to a lower sensitivity of ALL blasts to l-asparaginase, raising the possibility that transporter expression may be a predictive factor for therapy outcome.

Notably, among hematological malignancies, examples of amino acid auxotrophy are not restricted to ALL. For instance, human multiple myeloma is Gln-auxotrophic,49-52 and nutritional exchanges between cancer and stromal cells are highly likely, although the definition of the possible role of SNAT5 therein awaits further experimental work.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Fondazione Matilde Tettamanti, Comitato Maria Letizia Verga, Comitato Stefano Verri, the Department of Medicine and Surgery of the University of Milano-Bicocca, and GEICO TAIKI-SHA for their generous support. They would like to thank the Core Services and Advanced Technologies at the Cancer Research UK Beatson Institute (C596/A17196), with particular thanks to the Metabolomics facility. The equipment for the liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry experiments shown in Figures 2, 4B-F, and 5 was partly supported by the University of Parma through the Scientific Instrumentation Upgrade Programme 2018.

The research leading to these results has received funding from the Associazione Italiana Ricerca sul Cancro under IG 2019 - ID. 23354 project – P.I. Giovanna D'Amico. This study was partially supported by Cancer Research UK core grant number A17196, award 23982 to S.T. M.C. was supported by a fellowship of the Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (#19272). G.T. was supported by a short-term fellowship of European Molecular Biology Organization (STF_8177).

Authorship

Contribution: M.C., G.T., E.D., G.D., and O.B. designed the research, interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript; M.C., G.T., E.D., R.A., C.C., G.P., P.M., D.B., A.F., M.G.B., and L.G. performed experiments and data analysis; C.R., S.T., and A.B. read the manuscript and provided critical comments; and all authors have read and approved the final version.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: C.R. has received institutional grants for asparaginase pharmacological studies and fees for participation to advisory boards and invited lectures from the companies involved in marketing different asparaginase products. The other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

The current affiliation for D.B. is Department of Neurology and Laboratory of Neuroscience, Istituto Auxologico Italiano IRCCS, Cusano Milanino, Italy.

Correspondence: Ovidio Bussolati, Laboratory of General Pathology, Department of Medicine and Surgery, University of Parma, Via Volturno, 39, 43125 Parma Italy; e-mail: ovidio.bussolati@unipr.it; and Giovanna D’Amico, Centro Ricerca Tettamanti, Pediatric Department, University of Milano – Bicocca, Via Pergolesi, 33, 20900 Monza, Italy; e-mail: giovanna.damico@asst-monza.it.

References

Author notes

M.C., G.T., and E.D. contributed equally to this study.

G.D. and O.B. are joint senior authors.

For data sharing, please contact the corresponding authors at ovidio.bussolati@unipr.it or giovanna.damico@asst-monza.it.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.