Key Points

CD19CAR T-cell therapy for patients with primary CNS lymphoma is feasible and safe.

This case series demonstrates that IV-delivered CD19CAR T cells are promising for the treatment of primary CNS lymphoma.

Abstract

CD19-directed chimeric antigen receptor (CD19CAR) T-cell therapy has been successful in treating several B-cell lineage malignancies, including B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). This modality has not yet been extended to NHL manifesting in the central nervous system (CNS), primarily as a result of concerns for potential toxicity. CD19CAR T cells administered IV are detectable in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), suggesting that chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells can migrate from the periphery into the CNS, where they can potentially mediate antilymphoma activity. Here, we report the outcome of a subset of patients with primary CNS lymphoma (PCNSL; n = 5) who were treated with CD19CAR T cells in our ongoing phase 1 clinical trial. All patients developed grade ≥ 1 cytokine release syndrome and neurotoxicity post-CAR T-cell infusion; toxicities were reversible and tolerable, and there were no treatment-related deaths. At initial disease response, 3 of 5 patients (60%; 90% confidence interval, 19-92%) seemed to achieve complete remission, as indicated by resolution of enhancing brain lesions; the remaining 2 patients had stable disease. Although the study cohort was small, we demonstrate that using CD19CAR T cells to treat PCNSL can be safe and feasible. This trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT02153580.

Introduction

CD19-directed chimeric antigen receptor (CD19CAR) T cells have led to remarkable responses in B-cell malignancies, including non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL).1-3 Clinical trials evaluating chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells for NHL have largely excluded patients with central nervous system (CNS) lymphoma because of the fear of exacerbating potential neurotoxicity (NT) associated with CAR T cells.4,5 Yet, CD19CAR T cells administered IV are detectable in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF),6 suggesting that CAR T cells can migrate from the periphery into the CNS and mediate antilymphoma activity.7 Recent CD19CAR T-cell trials for NHL increasingly allow patients with secondary CNS lymphoma, and several reports have demonstrated the feasibility of treating patients with secondary CNS lymphoma with CD19CAR T cells.6-10 There is also a report describing an individual patient with primary CNS lymphoma (PCNSL) who was treated with a combination of CD19CAR and CD70CAR T cells.11 However, it has not been reported whether CD19CAR T cells delivered IV can expand and/or traffic to the CNS in the absence of systemic lymphoma.

Here, we describe outcomes for a subgroup of patients with PCNSL (n = 5), who were treated at City of Hope (COH) on our ongoing phase 1 clinical trial (NCT02153580), and demonstrate the safety and feasibility of CD19CAR T-cell monotherapy in patients with PCNSL treated on a CD19CAR T-cell clinical trial.

Methods

We performed a retrospective analysis on a patient cohort enrolled in our ongoing phase 1 clinical trial that was approved by the COH Institutional Review Board. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Overall trial eligibility includes adults with recurrent, progressive, or refractory NHL or chronic lymphocytic leukemia with confirmed CD19+ disease. Disease response for NHL uses Lugano criteria.12 Bridging therapy is allowed, including whole brain irradiation; imaging postbridging therapy is not required.

This subanalysis only describes patients with NHL who had PCNSL at enrollment. Patients received a fludarabine/cyclophosphamide-based lymphodepletion regimen prior to receiving CD19CAR T cells generated from autologous T naive/memory cells transduced with a CAR construct containing a CD28 costimulatory domain and coexpressing truncated epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR).13,14 Two dose levels (DLs) were tested: DL1 = 200 million (M) CAR+ cells and DL2 = 600M CAR+ cells. All patients received levetiracetam for seizure prophylaxis. Initial disease response was assessed by positron emission tomography and brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans on day 28 post–CAR T-cell infusion; complete resolution of enhancing lesion on MRI was considered complete remission (CR).

Patients were monitored for cytokine release syndrome (CRS) using Lee et al criteria15 and for all other toxicities using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v4.0. Patients who developed grade 2 CRS and NT could receive tocilizumab or dexamethasone at the discretion of the treating physician, according to COH standard operating procedures. Blood was collected via central line for correlative assays on day 0 and then weekly following CAR T-cell infusion for 4 of 5 patients. One patient declined all trial-related research studies following CAR T-cell infusion. CSF was collected at 3 time points for 1 of 5 patients. Blood and CSF were assessed for CAR T cells and lymphoma cells by flow cytometry and/or quantitative polymerase chain reaction to estimate lentiviral vector transgene copy number.

Results and discussion

As of October of 2020, we have treated 5 patients with PCNSL with CD19CAR T cells (Table 1). All patients had evidence of PCNSL (diffuse large B-cell lymphoma) at enrollment. The median age was 49 years (range, 42-53); all patients were female. The median number of prior therapies was 5 (range, 2-12; supplemental Table 1). Three patients received CD19CAR T cells at DL1, and 2 patients received CD19CAR T cells at DL2.

All patients developed grade ≥ 1 CRS and NT post–CD19CAR T-cell infusion (Table 1), with highest-grade CRS of 2 and highest-grade NT of 3. Two of 5 patients were treated with tocilizumab and dexamethasone. Both patients exhibited grade 2 CRS; 1 patient also had grade 3 NT, and the other patient also had grade 1 NT. The remaining 3 patients did not require treatment for CRS or NT. All 3 patients had grade 1 CRS, whereas 2 had grade 1 NT, and 1 had grade 2 NT. The highest-grade toxicity (grade 3 NT) manifested as headache lasting 3 days, starting at day +5 postinfusion, with severe pain limiting self-care for ≥1 day; the patient also had concurrent fever and cellulitis. Toxicities were reversible and tolerable, and there were no treatment-related deaths.

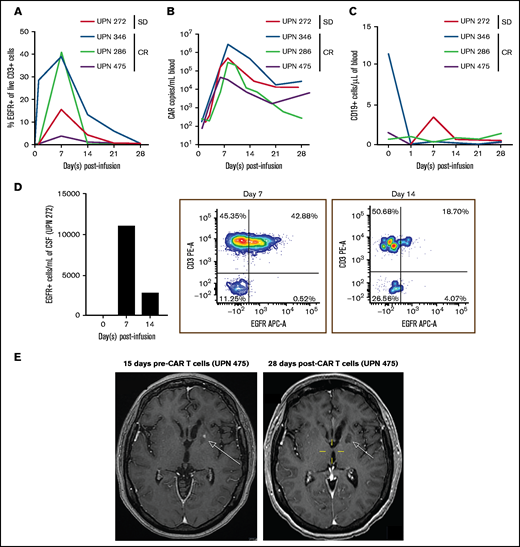

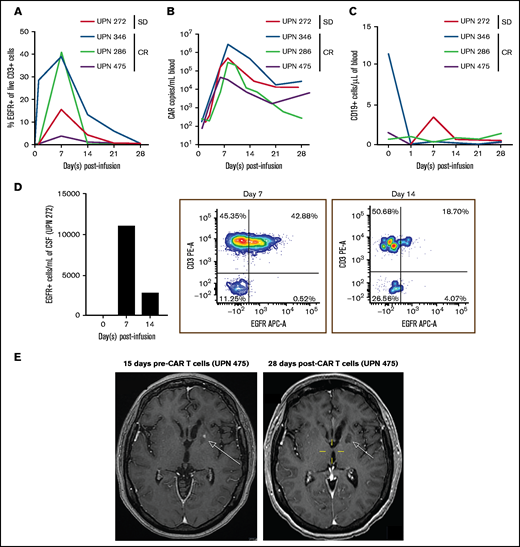

At initial disease response evaluation on day 28 postinfusion, 3 of 5 (60%; 90% confidence interval, 19-92%) patients seemed to achieve CR based on imaging; 2 patients had stable disease. Of those with CR, 1 progressed at day 273, 1 went on maintenance therapy at day 43, and 1 is still in follow-up without maintenance therapy at day 520. At last assessment, 4 of 5 patients were alive, and 1 patient was lost to follow-up. Blood collected from 4 of 5 patients during the 28 days postinfusion demonstrated CAR T-cell expansion by flow cytometry (Figure 1A) and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (Figure 1B), as well as the absence of CD19+ B cells or systemic lymphoma (Figure 1C). CSF collected from 1 patient showed CAR T cells by flow cytometry, demonstrating that IV-delivered CAR T cells could traffic to the CSF, despite the absence of systemic lymphoma (Figure 1D). In an image series for 1 patient with CR (Figure 1E), we observed a lesion pre–CAR T-cell infusion that was absent 28 days postinfusion. Patients with CR had small baseline lesions (Table 1), and it is possible that disease burden played a role in the response to IV CD19CAR T-cell therapy in the context of PCNSL.

Percentages of CAR T cells in the blood and CSF. (A) Persistence of EGFR+ CAR T cells in blood circulation of patients after CAR T-cell infusion on days 0, 1, 7, 14, 21, and 28. The percentage of EGFR+ T cells are gated from live CD3+ cells. (B) Expansion and persistence of CD19CAR T cells in blood of patients, as measured by Woodchuck post-transcriptional regulatory element (WPRE) copy number per milliliter of blood. (C) Levels of CD19+ cells in blood circulation after CAR T-cell infusion. CD19+ cells are gated from live cells. (D) Persistence of EGFR+ CAR T cells in CSF from unique patient number (UPN) 272 on day 0 and on days 7 and 14 post–T-cell infusion. Absolute cells per milliliter of CSF (left panel) and flow cytometry plots of CD3+ cell and EGFR+ cells on day 7 (middle panel) and on day 14 (right panel) post–CAR T-cell infusion. (E) Brain MRI series of UPN 475 pre–CAR T-cell infusion (left panel) and post–CAR T-cell infusion (right panel). Images are T1 weighted postcontrast axial. The pretherapy scan shows an enhancing lesion in the left basal ganglia (arrow) that is no longer present at 28 days post–CAR T-cell infusion. SD, stable disease.

Percentages of CAR T cells in the blood and CSF. (A) Persistence of EGFR+ CAR T cells in blood circulation of patients after CAR T-cell infusion on days 0, 1, 7, 14, 21, and 28. The percentage of EGFR+ T cells are gated from live CD3+ cells. (B) Expansion and persistence of CD19CAR T cells in blood of patients, as measured by Woodchuck post-transcriptional regulatory element (WPRE) copy number per milliliter of blood. (C) Levels of CD19+ cells in blood circulation after CAR T-cell infusion. CD19+ cells are gated from live cells. (D) Persistence of EGFR+ CAR T cells in CSF from unique patient number (UPN) 272 on day 0 and on days 7 and 14 post–T-cell infusion. Absolute cells per milliliter of CSF (left panel) and flow cytometry plots of CD3+ cell and EGFR+ cells on day 7 (middle panel) and on day 14 (right panel) post–CAR T-cell infusion. (E) Brain MRI series of UPN 475 pre–CAR T-cell infusion (left panel) and post–CAR T-cell infusion (right panel). Images are T1 weighted postcontrast axial. The pretherapy scan shows an enhancing lesion in the left basal ganglia (arrow) that is no longer present at 28 days post–CAR T-cell infusion. SD, stable disease.

Although the study cohort was small, we demonstrated that using CD19CAR T cells to treat PCNSL can be safe and feasible. We showed that CD19CAR T cells delivered IV could expand in the periphery and traffic to the CNS without stimulation by concurrent systemic lymphoma, consistent with Bishop et al, who reported expansion of the CD19CAR T-cell product tisagenlecleucel in patients without disease at infusion.16 A recent observation of CD19 expression by pericyte populations in the brain raises concern that targeting of these cells by CD19CAR T cells might contribute to NT.17 Our observation that patients with PCNSL treated with CD19CAR T cells developed reversible and tolerable grade ≤ 3 NT suggests that targeting of pericytes was probably not a major issue here, but this will need to be confirmed in a larger cohort of patients.

This trial was originally designed for patients with systemic disease; thus, several aspects of the trial were not ideal for patients with PCNSL, particularly disease response criteria and lack of postbridging imaging. However, data from this preliminary cohort indicates that CD19CAR T cells may be promising for treatment of PCNSL. We observed clinical improvement in 3 of 5 patients, including 1 durable response (Table 1). Therefore, we are planning a prospective trial to assess CD19CAR T cells specifically in patients with PCNSL. Preliminary in vivo mouse models of CNS lymphoma13,18 and other CNS disease19,20 indicate that intraventricular CAR T-cell administration is more efficacious than IV delivery. Thus, we plan to evaluate intraventricular delivery of CD19CAR T cells in patients with PCNSL. Other future avenues to investigate could include different targets and manufacturing platforms, among other variables. Overall, our data support further investigation into the use of CD19CAR T cells to treat PCNSL.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this article includes work performed in the GMP Manufacturing Core and the Biostatistics and Mathematical Modeling Core, which is supported by the National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute (grant P30CA002572).

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Authorship

Contribution: T.S., X.W., M.S.B., J.R.W., C.E.B., and S.J.F. designed the clinical trial; T.S., S.J.F., L.L.P., L.E.B., M.S.B., and J.R.W. executed the clinical trial; X.W., L.L., and V.V. contributed to correlative studies; T.S., M.C.C., X.W., M.S.B, and T.L.S. prepared the manuscript; and all authors analyzed and interpreted data and reviewed the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: T.S. has served on an Advisory Board for Juno Therapeutics, Celgene, Bristol Myers Squibb, and Kite Pharma. M.S.B. has received funding from Mustang Bio. L.L.P. has conflicts of interest with Pfizer Inc., Novartis Pharmaceuticals, and F. Hoffmann-La Roche AG. C.E.B. receives royalty payments and research support from Mustang Bio and Chimeric Therapeutics. L.E.B. has received research support from Mustang Therapeutics, Genentech, Inc., Merck, and Amgen and has acted as a consultant for Gilead and Novartis. S.J.F. has received Grant support and is a stock/shareholder and has intellectual property for Mustang Bio and is a Stock/shareholder for Lixte Bio. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Tanya Siddiqi, Department of Hematology and Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation, City of Hope Medical Center, 1500 E. Duarte Rd, Duarte, CA 91010; e-mail: tsiddiqi@coh.org.

References

Author notes

Data sharing requests should be sent to Tanya Siddiqi (tsiddiqi@coh.org).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.