Abstract

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) of the lower extremities can be associated with significant morbidity and may progress to pulmonary embolism and postthrombotic syndrome. Early diagnosis and treatment are important to minimize the risk of these complications. We systematically reviewed the accuracy of diagnostic tests for first-episode and recurrent DVT of the lower extremities, including proximal compression ultrasonography (US), whole leg US, serial US, and high-sensitivity quantitative D-dimer assays. We searched Cochrane Central, MEDLINE, and EMBASE for eligible studies, reference lists of relevant reviews, registered trials, and relevant conference proceedings. Two investigators screened and abstracted data. Risk of bias was assessed using Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies-2 and certainty of evidence using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation framework. We pooled estimates of sensitivity and specificity. The review included 43 studies. For any suspected DVT, the pooled estimates for sensitivity and specificity of proximal compression US were 90.1% (95% confidence interval [CI], 86.5-92.8) and 98.5% (95% CI, 97.6-99.1), respectively. For whole-leg US, pooled estimates were 94.0% (95% CI, 91.3-95.9) and 97.3% (95% CI, 94.8-98.6); for serial US pooled estimates were 97.9% (95% CI, 96.0-98.9) and 99.8% (95% CI, 99.3-99.9). For D-dimer, pooled estimates were 96.1% (95% CI, 92.6-98.0) and 35.7% (95% CI, 29.5-42.4). Recurrent DVT studies were not pooled. Certainty of evidence varied from low to high. This systematic review of current diagnostic tests for DVT of the lower extremities provides accuracy estimates. The tests are evaluated when performed in a stand-alone fashion, and in a diagnostic pathway. The pretest probability of DVT often assessed by a clinical decision rule will influence how, together with sensitivity and specificity estimates, patients will be managed.

Introduction

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) has an estimated incidence of 67 per 100 000 per year in the general population.1 Among those with DVT of the lower extremities, there is an increased risk of postthrombotic syndrome, pulmonary embolism, and death.2 Early diagnosis and clinical intervention are important for managing DVT and minimizing adverse consequences, as well as to exclude the diagnosis in those who do not have the disease, thereby avoiding added costs and risks of anticoagulant therapy.

DVT is usually unilateral and is clinically suspected in patients presenting with acute-onset pain, swelling, erythema and/or warmth of the lower extremity involved.3 These clinical manifestations are nonspecific and objective testing is required to confirm or exclude the diagnosis.4 Accurate diagnosis of DVT is important because patients incorrectly identified as having DVT (false positive) will be treated with anticoagulation and unnecessarily exposed to cost, inconvenience, and bleeding risk. On the other hand, patients incorrectly identified as not having DVT (false negative) are exposed to the potential risks of DVT extension and embolization in the absence of treatment. Consequently, diagnostic tests with high sensitivity and specificity for excluding or confirming a diagnosis of DVT are of utmost importance.

Diagnostic modalities for DVT include D-dimer assays and compression ultrasonography (US). D-dimer, a fibrin degradation product, is typically elevated in the presence of DVT. Although highly sensitive, D-dimer is frequently elevated in the presence of inflammation, malignancy, and other systemic illness and thus is nonspecific, necessitating additional testing if elevated (positive) or if the clinical probability for DVT is not low.5 Compression US evaluates the compressibility, or lack thereof, of a venous segment to diagnose thrombosis and is commonly coupled with a color Doppler to assess blood flow. With acute DVT, compressibility is lost secondary to passive distension of the vein by a thrombus.6 Compression US may be limited to the proximal leg veins (usually popliteal-trifurcation and more proximally) or may be performed on the entire leg (whole-leg US). US may also be performed sequentially, known as serial US.

The aim of this systematic review is to determine the accuracy of commonly available diagnostic tests for DVT of the lower extremities, which can be used to inform a combined strategy for diagnosis. Pooled estimates of sensitivity and specificity obtained in this systematic review were used to model different diagnostic strategies for patients with suspected lower extremity DVT. The results of modeling were used to inform evidence-based recommendations on diagnostic strategies for DVT in the American Society of Hematology clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis of venous thromboembolism.7

Methods

Search strategy and data sources

We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials from inception until May 2019. We also manually searched the reference lists of relevant articles and existing reviews. Studies published in any language were included in this review. We limited the search to studies reporting data for accuracy of diagnostic tests. The complete search strategy is available in Supplement 1. The prespecified protocol for this review is registered with PROSPERO (CRD42018083982). This review is reported in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) for diagnostic test accuracy guidelines.8

Study selection

Studies.

Studies reporting data on diagnostic test accuracy (cohort studies, cross-sectional studies) for lower extremity DVT were eligible for inclusion in this systematic review.

Participants.

Adult patients, ≥18 years of age, presenting to inpatient or outpatient settings with suspected first or recurrent episode of DVT of the lower extremity were eligible for inclusion.

Index tests for diagnosis.

Proximal compression US, whole-leg US, serial US, and quantitative high-sensitivity D-dimer assays (Vidas ELISA Assay, STA Liatest D-Di Assay, TinaQuant D-Dimer Assay, Innovance D-Dimer, HemoSIL D-Dimer Assay) were eligible index tests for diagnosis of lower extremity DVT. For proximal compression US, we considered only proximal DVT for test accuracy and excluded any incidental findings of distal DVT. For whole-leg US, both proximal and distal DVT were considered in test accuracy. Serial US was defined as a diagnostic strategy involving a repeat ultrasound for patients with initial negative US, and the complete strategy was considered for test accuracy rather than the repeat US alone. We did not exclude studies based on the duration when repeat US was conducted.

Reference standards.

Venography and/or clinical follow-up were eligible as a reference standard for proximal compression, whole-leg, or serial US strategies. US tests and/or clinical follow-up were considered appropriate reference standards for D-dimer assays. If a reference diagnostic test was not conducted, clinical follow-up for symptoms alone was sufficient as a reference standard.

Exclusion criteria.

Patients who were asymptomatic, pregnant, or had superficial thrombophlebitis with no DVT were excluded. Although studies reporting on both adult and pediatric patients were eligible for inclusion, we excluded studies with >80% of the study sample younger than 18 years of age, or if the mean age was less than 25 years. When possible, we extracted data separately for adult patients from these studies.

We also excluded studies that did not provide sufficient data to determine test accuracy (sensitivity and specificity), abstracts published before 2014 because the complete studies were likely published in peer-reviewed journals, and studies with sample size <100 patients to increase feasibility. A sensitivity analysis indicated that this would not affect the pooled test accuracy estimates. There were also concern regarding the quality of small test accuracy studies informing a clinical practice guideline; therefore, these studies were excluded.

Studies that used an unsuitable reference standard (impedance plethysmography, D-dimer) were excluded. We also excluded US studies that did not use compression to detect the presence of a thrombus and studies using US solely for the assessment of isolated calf DVT. D-dimer studies were excluded if they used assays that are no longer in use and/or are not highly sensitive (MDA, Asserachrom, Dimertest I, Enzygnost, Fibrinostika FbDP, Acculot, Wellcotest, Minutex), if they used a nonquantitative assay (SimpliRed) or if they considered a positive threshold other than the defined clinical cutoffs.

Screening and data extraction

Independent reviewers conducted title and abstract screening and full-text review in duplicate to identify eligible studies. Data extraction was also conducted independently and in duplicate and verified by a third author (R.A.M.). Disagreements were resolved by discussion to reach consensus, in consultation with 2 expert clinician scientists (R.A.M. and W.L.). Data extracted included general study characteristics (authors, publication year, country, study design), diagnostic index test and reference standard, prevalence of lower extremity DVT, and parameters to determine test accuracy (ie, sensitivity and specificity of the index test).

Risk of bias and certainty of evidence

We conducted the risk of bias assessment for diagnostic test accuracy studies using the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies-2 revised tool.9

The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) framework was used to assess overall certainty by evaluating the evidence for each outcome on the following domains: risk of bias, imprecision, inconsistency, indirectness, and publication bias.10,11

Data synthesis

The accuracy estimates from individual studies were combined quantitatively (pooled) for each test using OpenMetaAnalyst (http://www.cebm.brown.edu/openmeta/). We conducted a bivariate analysis for pooling sensitivity and specificity for each of the test comparisons to account for variation within and between studies. Forest plots were created for each comparison. The Breslow-Day test was used to measure the percentage of total variation across studies because of heterogeneity; however, the results did not influence our judgment of the pooled estimates because the literature has discouraged its use for test accuracy.12

Diagnostic strategies for lower extremity DVT are based on assessment of the pretest probability (PTP) for individual patients, which provides an estimate of the expected prevalence of DVT at a population level. Prevalence estimates for DVT were based on the Wells score, obtained from an individual patient level meta-analysis of 13 studies including 10 002 patients.13 The review reported an overall DVT prevalence of 19%, with an observed prevalence for patients with a low PTP ranging from 3.5% to 8.1%, intermediate 13.3% to 23.9%, and high 36.3% to 61.5%. We used similar disease prevalence estimates to determine the absolute differences in effects among patients with clinical suspicion of lower extremity DVT: 10% corresponding approximately to low PTP, 25% and 35% for intermediate PTP, and 50% and 75% for high PTP. We calculated the absolute differences in effects for each comparison as true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives. Here, we present the results for the low PTP population and results for intermediate and high PTP groups are reported in Supplement 2.

Results

Description of studies

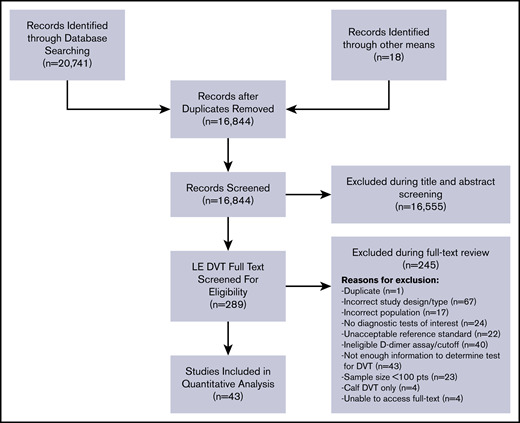

The initial search retrieved 16 844 nonduplicate studies, of which 289 were included for full-text review. Following full-text review, 38 were found to be eligible for data abstraction and inclusion in the systematic review. A list of excluded studies is provided in Supplement 3. Reasons for exclusion at full-text review were duplicates (1), ineligible study design (67), ineligible study population (17), no diagnostic tests of interest (24), unacceptable reference standards (22), D-dimer assays that were not highly sensitive or used nonclinical cutoffs (40), sample size <100 patients (n = 23), assessments of isolated calf DVT only (4), unable to obtain full texts (4), and studies that did not provide enough information to determine sensitivity and specificity (43). Figure 1 shows the study flow diagram for included studies.

Of the included studies, 41 reported on any suspected lower extremity DVT14-55 and 2 studies reported specifically on patients with recurrent DVT.56,57 Any suspected DVT studies reported the test accuracy of the following index tests: 13 studies on proximal compression US14-26 in comparison with a reference standard, 10 reported on whole-leg US,27-33,51-53 6 reported on serial US,14,18,34-37 and 16 reported on D-dimer for the diagnosis of DVT of the lower extremities.36,38-50,54,55 Studies assessing the accuracy of US used venography as a reference standard with some including clinical follow-up, whereas reference standards for D-dimer tests were mainly proximal compression or whole-leg US. Table 1 summarizes general characteristics of included studies, as well the index and reference standards. The majority of included studies were judged to be low risk of bias for patient selection, index test, and reference standard interpretation. Although there was unclear reporting regarding flow and timing in some studies, the certainty of evidence was generally not downgraded for risk of bias. The complete risk of bias assessment for individual studies is included in Supplement 4.

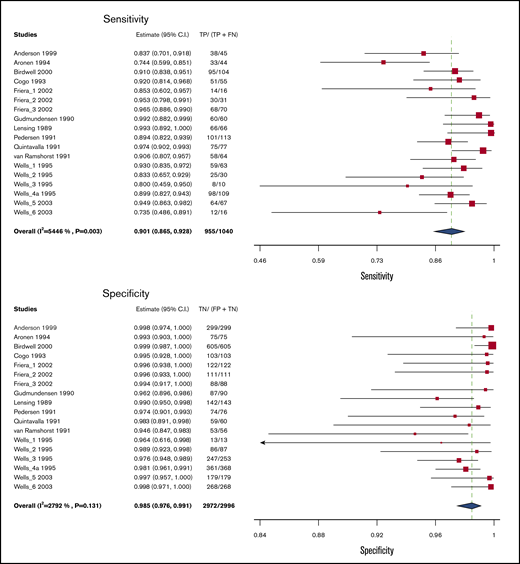

Proximal compression ultrasound

Test accuracy for proximal compression US was pooled from 13 studies, including 4036 participants.14-26 Studies used venography as a reference standard for proximal compression US, with some studies also including clinical follow-up. The pooled estimates for sensitivity and specificity of proximal compression US were 90.1% (95% confidence interval [CI], 86.5-92.8) and 98.5% (95% CI, 97.6-99.1), respectively. Figure 2 shows the forest plot displaying the sensitivity and specificity from individual studies and the pooled estimates.

Pooled sensitivity and specificity of proximal compression ultrasound for diagnosis of lower extremity DVT.

Pooled sensitivity and specificity of proximal compression ultrasound for diagnosis of lower extremity DVT.

Proximal compression US results were illustrated for 1000 patients from a low prevalence population undergoing the test, and absolute differences indicate a low (<5%) proportion of false-negative and false-positive results. Overall, the test was shown to be highly sensitive and specific and the certainty of evidence was high. Table 2 shows the summary of findings.

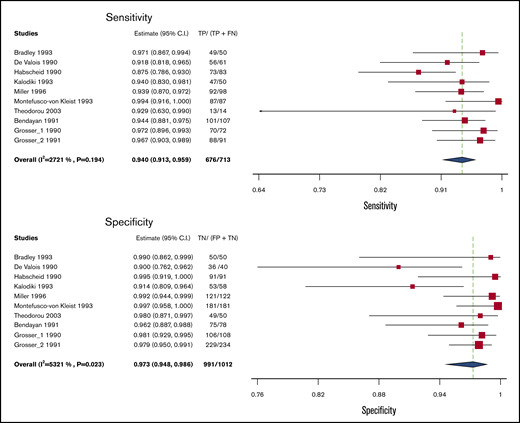

Whole-leg ultrasound

Test accuracy for whole-leg US was pooled from 10 studies, including 1725 participants.27-33,51-53 All studies assessing whole-leg US used venography as a reference standard. The pooled estimates for sensitivity and specificity of whole-leg US were 94.0% (95% CI, 91.3-95.9) and 97.3% (95% CI, 94.8-98.6), respectively. Figure 3 shows the forest plot displaying the sensitivity and specificity from individual studies and the pooled estimates.

Pooled sensitivity and specificity of whole leg ultrasound for diagnosis of lower extremity DVT.

Pooled sensitivity and specificity of whole leg ultrasound for diagnosis of lower extremity DVT.

Whole-leg US results were illustrated for 1000 patients from a low-prevalence population undergoing the test, and absolute differences indicate a low (<5%) proportion of false-negative and false-positive results. Overall, the test was shown to be highly sensitive and specific and the certainty of evidence was high. Table 3 shows the summary of findings.

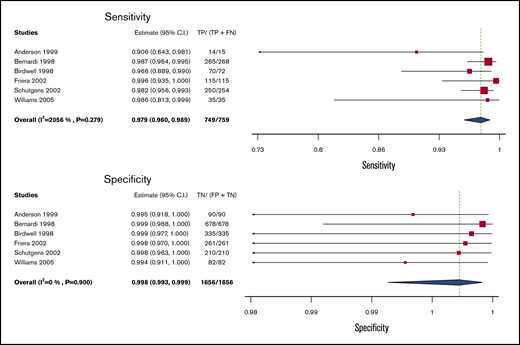

Serial US

Test accuracy for serial US was pooled from 6 studies, including 2415 participants.14,18,34-37 The complete serial US strategy was considered as the index test (rather than a single repeat US), and clinical follow-up alone was taken as the reference standard. The pooled estimates for sensitivity and specificity of serial US were 97.9% (95% CI, 96.0-98.9) and 99.8% (95% CI, 99.3-99.9), respectively. Figure 4 shows the forest plot displaying the sensitivity and specificity from individual studies and the pooled estimates.

Pooled sensitivity and specificity of serial ultrasound for diagnosis of lower extremity DVT.

Pooled sensitivity and specificity of serial ultrasound for diagnosis of lower extremity DVT.

Serial US results were illustrated for 1000 patients from a low-prevalence population undergoing the test, and absolute differences indicate a low (<5%) proportion of false-negative and false-positive results. Overall, the test was shown to be highly sensitive and specific and the certainty of evidence was high. Table 4 shows the summary of findings.

D-dimer

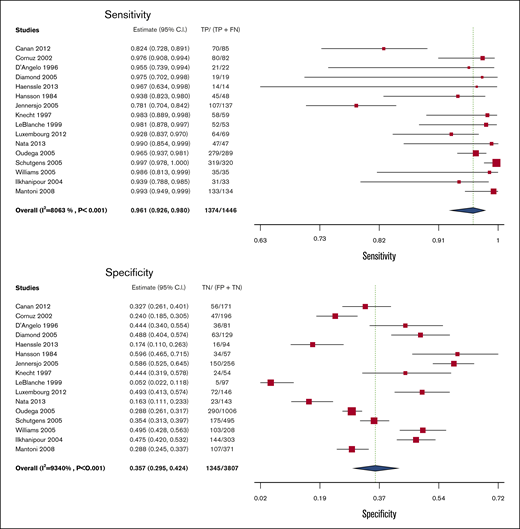

Test accuracy for D-dimer was pooled from 16 studies, including 5253 participants.36,38-50,54,55 All of the D-dimer studies used proximal compression or whole-leg US as reference standards, with some studies also including venography and clinical follow-up. The pooled estimates for sensitivity and specificity of the D-dimer assays were 96.1% (95% CI, 92.6-98.0) and 35.7% (95% CI, 29.5-42.4), respectively. Figure 5 shows the forest plot displaying the sensitivity and specificity from individual studies and the pooled estimates.

Pooled sensitivity and specificity of D-dimer for diagnosis of lower extremity DVT.

Pooled sensitivity and specificity of D-dimer for diagnosis of lower extremity DVT.

D-dimer results were illustrated for 1000 patients from a low prevalence population undergoing the test, and absolute differences indicate a low (<5%) proportion of false-negative results and a high proportion of false-positive results (>5%). Overall, the test was shown to be highly sensitive but had low specificity. The certainty of evidence was moderate. Table 5 shows the summary of findings.

Recurrent DVT

Two studies reported on diagnosis for recurrent DVT of the lower extremities,56,57 1 of which reported on a diagnostic strategy. The strategy included D-dimer for low-PTP patients followed by proximal compression US if positive and 3-month follow-up if negative, whereas high-PTP patients had proximal compression US followed by 1-week repeat US if positive and negative ruled out DVT.56 The second study reported on proximal compression US alone and a serial US strategy among recurrent DVT patients.57 We modeled the test accuracy for the strategies for 1000 patients at a prevalence of 15% corresponding to low PTP of recurrence and 40% for high PTP of recurrence. In the studies, the reported prevalences of recurrent DVT were 27%56 and 37%57 from a combination of low- and high-PTP patients. There was low certainty in the evidence because of imprecision. Tables 6-8 show the summary of findings.

Discussion

This review presents pooled estimates of test accuracy for commonly available diagnostic methods for DVT of the lower extremities. The certainty of evidence was moderate to high for studies of first-episode DVT and low for recurrent DVT. Of the evaluated tests, serial US had the highest sensitivity (97.9% [95% CI, 96.0-98.9%]) and specificity (99.8% [95% CI, 99.399.9]), although resources for, and availability of, serial US may be limited. Proximal compression US and whole-leg US also had optimal and comparable sensitivity and specificity with regard to detection of proximal DVT. Because the objective was to evaluate the diagnostic test characteristics of these studies, we did not specifically evaluate studies comparing proximal vs whole-leg US on clinically relevant outcomes such as pulmonary embolism. Recommendations for whether compression should be limited to the proximal veins or extended to the whole leg are, therefore, outside the scope of this review and availability, test cost, and patient/provider preference can likely inform the use of these tests. D-dimer also had high sensitivity (95.8% [95% CI, 91.8-97.9]) and can be a cost-effective and accessible approach for excluding DVT in patients with low PTP. However, the specificity of D-dimer testing is low; therefore, a positive result must be followed with a more specific diagnostic test, usually US.

This review has several strengths. The comprehensive and systematic approach for identifying studies makes it unlikely that relevant studies were missed. Additionally, we did not limit our review by language and translated articles that were not published in English. Finally, we assessed the certainty of evidence in this area and identified sources of bias.

We note a few limitations in this comprehensive systematic review. We did not consider whether Doppler ultrasonography was used alongside compression, and studies were included if there was a description that compression of venous segments was performed. This decision was based on evidence suggesting that compression US is sufficient for diagnosis with no added benefit of Doppler.58 Nonetheless, we acknowledge that many institutions use Doppler for assessment of venous flow and some of the included studies may have also performed Doppler alongside compression. In addition, US is an operator-dependent diagnostic test.59 Last, the diagnostic test accuracy estimates were determined for a test done in a stand-alone manner, and we did not consider combinations of tests in a pathway for establishing a diagnosis of lower extremity DVT. This may be required, for example, in patients who have a low PTP but have a positive D-dimer. The pooled sensitivity and specificity estimates of the tests from this review only apply when the test is performed alone; however, they can be used to model various diagnostic strategies to inform clinical decision making. Ultimately, the diagnostic tests will be used in a strategic approach based on clinical pretest probability and with consideration of availability, cost, and patient and provider values and preferences.

In conclusion, this comprehensive systematic review synthesizes and evaluates the accuracy of commonly used tests for the diagnosis of DVT of the lower extremities. Estimates of sensitivity and specificity from this review were used to model diagnostic strategies and inform evidence-based recommendations for a clinical practice guideline.7 For clinical decision making, the prevalence or pretest probability for DVT in a population will influence how, together with the sensitivity and specificity estimates, patients will be managed.

For data sharing requests, please e-mail the corresponding author, Reem A. Mustafa.

Acknowledgments

The systematic review team acknowledges Samantha Eiffert and Robin Arnold for their assistance with data management and organization of the manuscript and Jane Skov and Itziar Etxeandia for their assistance with translation of studies.

This systematic review was conducted to support the development of the American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: diagnosis of venous thromboembolism. The entire guideline development process was funded by the American Society of Hematology. Through the McMaster GRADE Center, some researchers received salary or grant support; others participated to fulfill requirements of an academic degree or program or volunteered their time.

Authorship

Contribution: M.B. contributed to study design, search strategy, study selection, data extraction, statistical analysis, and drafting the report; C.B., Payal Patel, and Parth Patel contributed to study design, study selection, data extraction, statistical analysis, and critical revision of the report; H.B., N.M.H., M.A.K., and Y.N.A.J. contributed to the data extraction, statistical analysis, interpretation of results, and critical revision of the report; J.V., D.W., H.J.A., M.T., M.B., W.B., R. Khatib, R. Kehar, R.P., A.S., and A.M. contributed to study selection, data extraction, and critical revision of the report; and W.W., R.N., W.L., S.M.B., E.L., G.L.G., M.R., H.J.S., and R.A.M. contributed to the study design, interpretation of the results, and critical revision of the report.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: H.J.S. and R.A.M. received research support from American Society of Hematology (ASH), and W.W. received salary support through the ASH grant. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Reem A. Mustafa, Division of Nephrology and Hypertension, Department of Medicine, University of Kansas Medical Center, 3901 Rainbow Blvd, MS3002, Kansas City, KS 66160; e-mail: ramustafa@gmail.com.

References

Author notes

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.