Key Points

Activated, but not nonactivated, αIIbβ3 plays a dominant role in platelet adhesion to D-dimer, a fragment of cross-linked fibrin.

D-dimer interacts with αIIbβ3 via a mechanism(s) distinct from the interaction of fibrinogen with αIIbβ3 and inhibits clot retraction.

Abstract

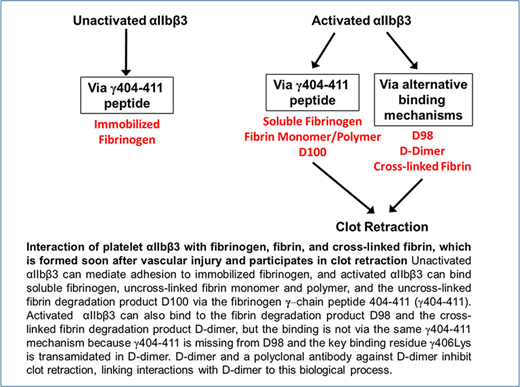

Although much is known about the interaction of fibrinogen with αIIbβ3, much less is known about the interaction of platelets with cross-linked fibrin. Fibrinogen residue Lys406 plays a vital role in the interaction of fibrinogen with αIIbβ3, but because it participates in fibrin cross-linking, it is not available for interacting with αIIbβ3. We studied the adhesion of platelets and HEK cells expressing normal and constitutively active αIIbβ3 to both immobilized fibrinogen and D-dimer, a proteolytic fragment of cross-linked fibrin, as well as platelet-mediated clot retraction. Nonactivated platelets and HEK cells expressing normal αIIbβ3 adhered to fibrinogen but not D-dimer, whereas activated platelets as well as HEK cells expressing activated αIIbβ3 both bound to D-dimer. Small-molecule antagonists of the αIIbβ3 RGD (Arg-Gly-Asp) binding pocket inhibited adhesion to D-dimer, and an Asp119Ala mutation that disrupts the β3 metal ion–dependent adhesion site inhibited αIIbβ3-mediated adhesion to D-dimer. D-dimer and a polyclonal antibody against D-dimer inhibited clot retraction. The monoclonal antibody (mAb) 10E5, directed at αIIb and a potent inhibitor of platelet interactions with fibrinogen, did not inhibit the interaction of activated platelets with D-dimer or clot retraction, whereas the mAb 7E3, directed at β3, inhibited both phenomena. We conclude that activated, but not nonactivated, αIIbβ3 mediates interactions between platelets and D-dimer, and by extrapolation, to cross-linked fibrin. Although the interaction of αIIbβ3 with D-dimer differs from that with fibrinogen, it probably involves contributions from regions on β3 that are close to, or that are affected by, changes in the RGD binding pocket.

Introduction

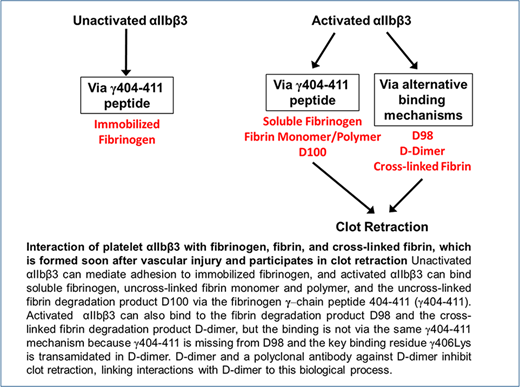

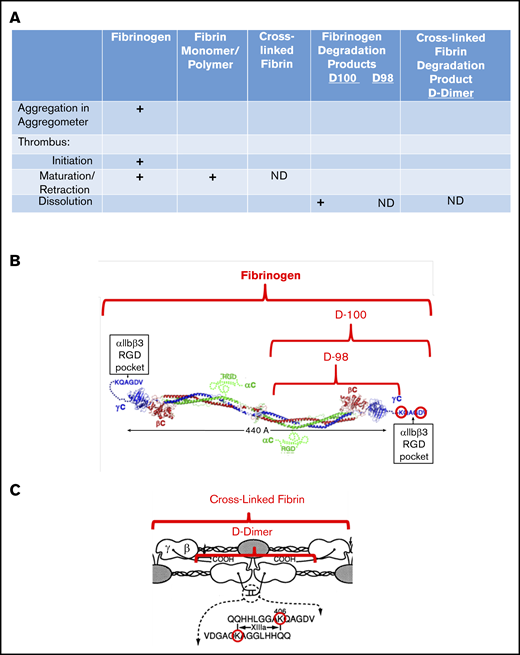

The interaction of platelets with fibrinogen has been studied extensively, but much less is known about the interaction of platelets with cross-linked fibrin, the dominant form of fibrinogen in human thrombi,1-3 and thus the form that is likely to participate in clot retraction.4 The primary interaction supporting fibrinogen binding and platelet aggregation occurs between the C-terminal region of the fibrinogen γ-chain, the γ404-411 sequence, and the “RGD (Arg-Gly-Asp)-binding pocket” in the integrin headpiece that is formed jointly by the αIIb β-propeller and β3 β-I domains.5,6 This interaction requires agonist-induced activation of αIIbβ3 when fibrinogen is in solution, but not when fibrinogen is immobilized,7 and it may also support the interaction of platelets with fibrin monomers and polymers, which retain the γ404-411 sequence during thrombus initiation and early maturation (Figure 1). It may also play a role in mediating the interaction of platelet αIIbβ3 with the plasmin-induced fibrinogen degradation product D100, which also retains the γ404-411 sequence.8

Interaction of fibrin(ogen) with platelet αIIbβ3 during different phases of thrombus development. (A) Chart showing the interactions of platelet αIIbβ3 with fibrinogen, fibrin monomer and polymer, cross-linked fibrin, and fibrinogen degradation products D100, D98, and D-dimer, as a function of thrombus maturation. Interactions mediated by fibrinogen γ404-411 with the αIIbβ3 RGD binding pocket are indicated by plus signs, and those that are not yet defined are indicated by ND. (B) Schematic of fibrinogen (adapted from Yang et al9 and Springer et al6 with permission) highlighting the γ406-411 region and indicating the D100 and D98 plasmin fragments of fibrinogen. (C) Schematic of cross-linked fibrin, highlighting the location of the fibrinogen γ-chain residue Lys406, the FXIIIa-mediated cross-links, and the plasmin fragment D-dimer (adapted from Mosesson et al10 with permission; ©1989 National Academy of Sciences).

Interaction of fibrin(ogen) with platelet αIIbβ3 during different phases of thrombus development. (A) Chart showing the interactions of platelet αIIbβ3 with fibrinogen, fibrin monomer and polymer, cross-linked fibrin, and fibrinogen degradation products D100, D98, and D-dimer, as a function of thrombus maturation. Interactions mediated by fibrinogen γ404-411 with the αIIbβ3 RGD binding pocket are indicated by plus signs, and those that are not yet defined are indicated by ND. (B) Schematic of fibrinogen (adapted from Yang et al9 and Springer et al6 with permission) highlighting the γ406-411 region and indicating the D100 and D98 plasmin fragments of fibrinogen. (C) Schematic of cross-linked fibrin, highlighting the location of the fibrinogen γ-chain residue Lys406, the FXIIIa-mediated cross-links, and the plasmin fragment D-dimer (adapted from Mosesson et al10 with permission; ©1989 National Academy of Sciences).

Because vascular injury initiates sufficient thrombin generation within 20 seconds to result in fibrin deposition,11,12 it is likely that the dominant fibrinogen species in maturing and mature thrombi, as well as during clot retraction, is cross-linked fibrin. Cross-linked fibrin is produced by the sequential actions of thrombin and activated factor XIII, with the latter catalyzing reciprocal transamidation of the C-terminal γ-chain peptides from adjacent fibrinogen molecules1-3 (Figure 1). αIIbβ3 appears to be necessary for platelets to interact with fibrin during clot retraction, given that patients with Glanzmann thrombasthenia, who lack this receptor or have an abnormal receptor, have diminished or absent clot retraction.13-15 Investigators have, however, variably reported that platelet interactions with fibrin can be supported by glycoprotein (GP) VI (reviewed by Slater et al16 ) and GPIb, either directly or through interactions with von Willebrand factor,17-23 leaving open the possibility that αIIbβ3 is not required for clot retraction.

Several findings suggest that the sites on αIIbβ3 involved in fibrin binding may be different from those involved in fibrinogen binding:

The side chain of fibrinogen γ-chain residue Lys406, which has an important ionic interaction with αIIb residue Lys224 to support fibrinogen binding,6 is cross-linked to Gln398/Gln399.24

Multiple sites on fibrinogen other than the γ404-411 sequence and on αIIbβ3 other than the RGD binding pocket have been proposed to mediate interactions between fibrin and αIIbβ3,25,26 including new sites on fibrin exposed only after the conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin and detectable by monoclonal antibodies (mAbs).27,28

Single-molecule experiments demonstrate that fibrin made from γ′/γ′-fibrinogen, which lacks the γ404-411 sequence, interacts as well or better with purified αIIbβ3.26

EDTA treatment of αIIbβ3, which irreversibly alters its ability to bind fibrinogen, does not inhibit clot retraction.29,30

Activated αIIbβ3 can support adhesion to an immobilized fibrinogen fragment that lacks the γ406-411 sequence (D98).8

In addition to differences in molecular interactions that define the affinity of platelet-fibrin vs platelet-fibrinogen interactions, platelet interactions with fibrin also differ from those with fibrinogen with regard to ligand valency, because fibrinogen is dimeric, but polymerized fibrin is highly multivalent. This multivalency may contribute to greater avidity, even with the same receptor-ligand affinity, if multiple receptors on a single platelet can interact with multiple ligand sites on polymerized fibrin.31,32 High avidity may also contribute to the adhesion of platelets to fibrinogen immobilized at high density, even without platelet activation.7

To address both the molecular basis of the interaction of platelets with cross-linked fibrin, as well as the impact of its multivalency, we have now assessed the interaction of platelets and cells expressing recombinant αIIbβ3 with D-dimer, a product of cross-linked fibrin known to circulate in humans as a function of activation of the coagulation and fibrinolytic pathways,33 and by inference, of cross-linked fibrin itself.

Materials and methods

Fibrinogen, fibrinogen fragments, and mAbs

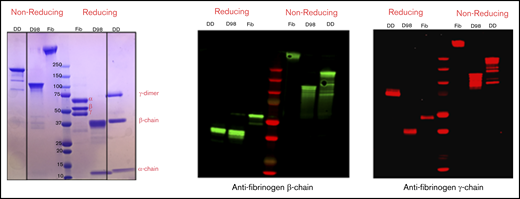

Human fibrinogen was obtained from Enzyme Research Labs (South Bend, IN) and fibrinogen fragment D98 and D-dimer were obtained from Haematologic Technologies, Inc (Essex Junction, VT). The preparation and characterization of fragment D98 has been described previously.8 D-dimer was prepared from cross-linked fibrin obtained from human plasma clotted with thrombin by a modification of the method of Masci et al.34 The purified D-dimer was characterized by immunoblot analysis, using antibodies directed against the fibrinogen α (mAb 108616), β (polyclonal antibody [pAb] 219355), and γ chains (pAb 137728; all from Abcam, Cambridge, MA), including mAb 7E9, which is directed at the γ12 peptide at the C terminus of the γ chain.24

We previously described our mAbs 10E5 (anti-αIIb cap domain),35,36 7E3 (anti-β3 near the metal ion-dependent adhesion site [MIDAS]),37,38 and 7H2 (anti-β3 PSI domain),39 produced at the National Cell Culture Center (Minneapolis, MN). Alexa488 labeling of 10E5, 7E3, and 7H2 was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Alexa488-labeled fibrinogen was obtained from Invitrogen/Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA).

Control purified rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) was obtained from New England Peptide (Gardner, MA).

Negative-stain EM sample preparation, data collection, and image processing

An aliquot of D-dimer solution at a concentration of 5 ng/mL was applied to a glow-discharged electron microscopy (EM) grid covered with a thin carbon layer. After 30 seconds, the grid was blotted and washed twice with deionized water and stained with uranyl formate, as described.40 The dried grid was loaded into a Philips CM10 electron microscope operated at an acceleration voltage of 100 kV. Images were recorded at a calibrated magnification of ×41 513, yielding a pixel size of 2.65 Å at the specimen level. A total of 10 054 particles were manually selected from 33 micrographs, using e2boxer.py.41 The particles were extracted into 160 × 160-pixel images, centered, and normalized. For quantification, the particles were classified into 100 groups by using the k-means classification procedures implemented in SPIDER.42 Class averages that showed clear structural features were assigned to represent dimers in a “straight” or “bent” conformation; the remaining averages were not assigned. To generate class averages with the clearest structural features, we resized the particle images to 64 × 64 pixels and centered and subjected them to classification with the iterative stable alignment and clustering (ISAC) algorithm,43 specifying 100 images per group and a pixel error threshold of 0.7. After 10 generations, 181 averages were obtained.

Generation of mutants and stable cell lines

The αIIbFFβ3, αIIbβ3 Asp119Ala (D119A), and αIIbβ3 mutants were made, sorted based on the binding of Alexa488-conjugated mAb 7H2, and labeled with calcein, as described previously.8 Surface expression of the normal and mutant receptors was analyzed by flow cytometry, using mAbs 10E5, 7E3, and/or 7H2.

Platelet and cell adhesion assay

Ninety-six–well polystyrene plates were coated with fibrinogen or fibrinogen fragments and blocked with 1× HEPES-modified Tyrode buffer (HBMT), as described previously.8 Washed platelets prepared from healthy donors’ blood or cells expressing normal or mutant αIIbβ3 were prepared as previously described.8 After labeling with calcein, HEK cells or washed platelets were resuspended at 2 × 106/mL in HBMT containing 2 mM Ca2+ and 1 mM Mg2+. EDTA (10 mM), the small-molecule αIIbβ3 antagonists eptifibatide (100 µM) or tirofiban (10 µM) or mAbs 10E5 and 7E3 (both at 50 µg/mL) were added to the cell or platelet suspensions for 20 minutes at room temperature before cells or platelets were added to the wells. When indicated, platelets were activated by adding a thrombin receptor-activating peptide (SFLLRN; T6) to the wells at 25 µM before adding the platelets. After washing away nonadherent cells or platelets, cell and platelet adhesion was measured as follows:

HEK-adhesion experiments: the fluorescence of the adherent HEK cells was measured at 480 nM with a fluorescent plate reader (Synergy Neo, BioTek, Winooski, VT) and reported in arbitrary fluorescence intensity units or as a percentage of the adhesion of control cells tested in the same experiment. In experiments comparing different cell lines, the arbitrary fluorescence unit value was normalized based on the surface expression of αIIbβ3, as judged by binding of 10E5, 7E3, or 7H2.

Platelet-adhesion experiments: adherent platelets were lysed and the released acid phosphatase activity was measured by adding phosphatase substrate (EC 224-246-5; MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA) at 2 mg/mL in 0.1 M Na citrate (pH 5.6) and 0.1% Triton X-100 for 1 hour at room temperature and stopping the reaction by adding 50 mL 2 M NaOH, and analyzing the samples in a spectrophotometer at 405 nm. Adhesion is reported in arbitrary adhesion units (AU) that represent optical density.

Generation of a pAb that targets D-dimer

Two rabbits were immunized with 400 µg purified D-dimer in Freund’s adjuvant on day 1, with boosts of 200 µg of D-dimer in incomplete Freund’s adjuvant on days 14 and 28. Blood was drawn on days 35 and 40 and evaluated by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, using immobilized D-dimer. The serum from 1 animal had a titer of 1/680 900 and was used to prepare purified IgG using protein G affinity chromatography. The antisera, but not the preimmunization serum, reacted with D-dimer by immunoblot. Control purified rabbit IgG was obtained from New England Peptide.

Clot retraction

Clot retraction was performed with washed platelets from healthy donors at a concentration of 3 × 108 platelets per milliliter in HBMT containing 1 mM Mg2+ as previously described.44 Platelet suspensions were preincubated with D98, D-dimer, or bovine serum albumin (BSA) at 200-µg/mL final concentration for 10 minutes at 37°C, or with various concentrations of the anti–D-dimer pAb, or with 50 µg/mL of 10E5 or 7E3. Clot retraction was induced by adding 300 µL of a platelet preparation, at room temperature, to a glass cuvette containing 0.2 U/mL human thrombin (HCT-0020; Hematologic Technologies Inc) and 1 mM CaCl2. Clot retraction was recorded by taking photos of the clots at timed intervals and then analyzing the images for the area of the clot with NIH Image J software. To assess fibrin cross-linking after initiating clot retraction, we removed aliquots at time 0 and 20 minutes and performed immunoblot analysis with an antibody to the fibrinogen γ chain. (pAb 137728; Abcam).

Statistics

Results are expressed as the mean number of observations ± standard deviation. Since the normalcy of data cannot be robustly assessed with a small number of replicates, all of the data points are presented for inspection. Data were analyzed with Prism, v.6.07 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA). Comparison between samples was determined by the Student t test. Differences were considered significant at P ≤ .05.

This study was approved by the Rockefeller University Institutional Review Board (BCO726).

Results

Characterization of D-dimer by immunoblot and negative-stain EM

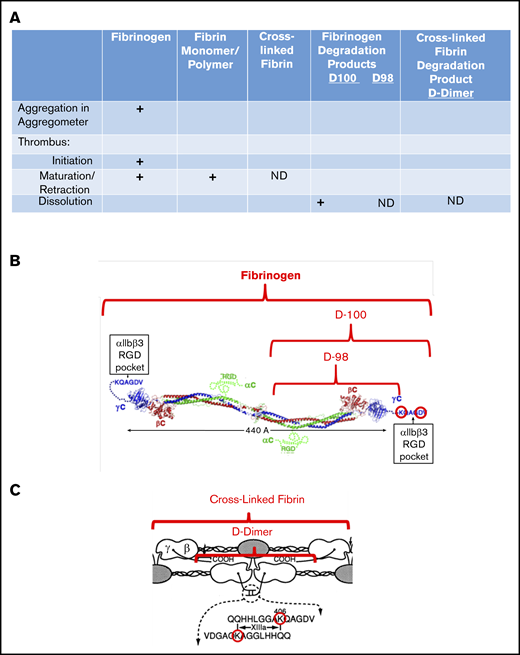

By SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis with antibodies specific for the fibrinogen-α, -β, and -γ chains, nonreduced samples of purified D-dimer migrated as a major band of molecular mass (Mr) ∼200 kDa, with minor bands at ∼150, 130, and 90 kDa, whereas D98 migrated as previously described8 as a major band at ∼110 kDa (Figure 2). After reduction, D-dimer was found to consist of a γ-chain dimer of Mr ∼70 kDa, β chains of Mr ∼40 kDa, and α chains of Mr ∼12 kDa.

Characterization of fibrinogen, D98, and D-dimer under reducing and nonreducing conditions by Coomassie blue staining and immunoblot analysis with antibodies specific for the fibrinogen β- and γ-chains. The locations of the intact α-, β-, and γ-chains of fibrinogen (Fib) are indicated in the Coomassie blue–stained reduced sample. The immunoblot of reduced D-dimer (DD) indicates that virtually all of the γ-chains in D-dimer are in the form of γ-γ dimers.

Characterization of fibrinogen, D98, and D-dimer under reducing and nonreducing conditions by Coomassie blue staining and immunoblot analysis with antibodies specific for the fibrinogen β- and γ-chains. The locations of the intact α-, β-, and γ-chains of fibrinogen (Fib) are indicated in the Coomassie blue–stained reduced sample. The immunoblot of reduced D-dimer (DD) indicates that virtually all of the γ-chains in D-dimer are in the form of γ-γ dimers.

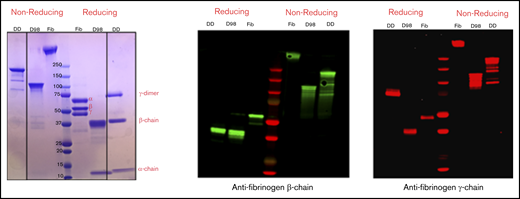

Negative-stain EM of purified D-dimer revealed that the molecules adopt linear as well as variably angulated and bent conformations with a beaded appearance (Figure 3A). Classification of 10 054 particles manually selected using the ISAC algorithm43 showed 7 beads in the best-defined class averages, but in most averages, the beads farthest from the center were not well-resolved (Figure 3B). Angulations were identifiable between each bead, and in some class averages the bending resulted in nearly circular forms, indicating considerable molecular flexibility. To estimate the conformational distribution, the particles were classified into 100 classes by using k-means classification (Figure 3C). Twenty-six class averages, accounting for 1754 particles (17%), could not be unambiguously assigned (averages with black borders). Of the remaining classes, 50 classes, accounting for 5852 particles (71%), were assigned as showing the D-dimer in a straight conformation (averages with green borders), and 24 classes, accounting for 2448 particles (29%), were assigned as showing it in a bent conformation (averages with red borders).

Analysis of D-dimer by negative-stain EM. (A) A typical image area of negatively stained D-dimer. The bar represents 100 nm. (B) The 181 class averages obtained with the ISAC algorithm.43 (C) The 100 class averages obtained by k-means classification shown from the most populous class on the top left to the least populous class at the bottom right. Averages were assigned to show D-dimers in a straight conformation (green boxes) or in a bent conformation (red boxes) or were not assigned if the features were ambiguous (black boxes). The numbers in the lower left corner of each average in panels B and C indicate the number of particles in the class; the side length of the individual averages is 42.4 nm.

Analysis of D-dimer by negative-stain EM. (A) A typical image area of negatively stained D-dimer. The bar represents 100 nm. (B) The 181 class averages obtained with the ISAC algorithm.43 (C) The 100 class averages obtained by k-means classification shown from the most populous class on the top left to the least populous class at the bottom right. Averages were assigned to show D-dimers in a straight conformation (green boxes) or in a bent conformation (red boxes) or were not assigned if the features were ambiguous (black boxes). The numbers in the lower left corner of each average in panels B and C indicate the number of particles in the class; the side length of the individual averages is 42.4 nm.

Platelet adhesion

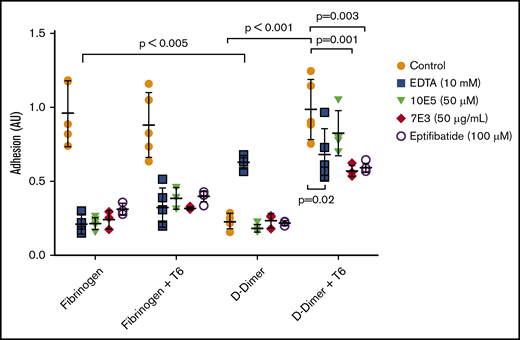

Nonactivated platelets adhered readily to immobilized fibrinogen, but adhered poorly to D-dimer (Figure 4). Activation of platelets with 25 µM of the thrombin receptor–activating peptide T6 had no impact on their adhesion to fibrinogen, but increased their adhesion to D-dimer 4.5-fold (mean control = 0.22 AU vs mean T6-treated = 0.98 AU; P < .001; n = 5). We concluded that platelet activation is required for adhesion to D-dimer, as we previously reported for platelet adhesion to D98.8

Activated, but not nonactivated platelets, adhere well to D-dimer, and the adhesion is inhibited by 7E3 and eptifibatide, but not by 10E5. EDTA enhances adhesion of nonactivated platelets to D-dimer. Washed platelets were either not activated or were activated with T6 (25 μM) and then added to wells precoated with fibrinogen or D-dimer. After 1 hour, the wells were washed, and residual platelet adhesion was assessed by measuring residual alkaline phosphatase activity, reported as optical density adhesion units (AU). In some experiments, EDTA (10 mM), 10E5 and 7E3 (both 50 μg/mL), or eptifibatide (100 μM) was incubated with the platelets for 20 minutes at room temperature before the platelets were added to the wells; n = 5 (5 different experiments with 3 replicates of each condition) for all conditions except for studies of 7E3 and eptifibatide, where n = 3 (3 different experiments with 3 replicates of each condition).

Activated, but not nonactivated platelets, adhere well to D-dimer, and the adhesion is inhibited by 7E3 and eptifibatide, but not by 10E5. EDTA enhances adhesion of nonactivated platelets to D-dimer. Washed platelets were either not activated or were activated with T6 (25 μM) and then added to wells precoated with fibrinogen or D-dimer. After 1 hour, the wells were washed, and residual platelet adhesion was assessed by measuring residual alkaline phosphatase activity, reported as optical density adhesion units (AU). In some experiments, EDTA (10 mM), 10E5 and 7E3 (both 50 μg/mL), or eptifibatide (100 μM) was incubated with the platelets for 20 minutes at room temperature before the platelets were added to the wells; n = 5 (5 different experiments with 3 replicates of each condition) for all conditions except for studies of 7E3 and eptifibatide, where n = 3 (3 different experiments with 3 replicates of each condition).

We further tested the effects of inhibitors of the interaction of αIIbβ3 with fibrinogen, including 10E5 and 7E3 and the small-molecule inhibitor eptifibatide. All significantly decreased the adhesion of nonactivated platelets to fibrinogen (P < .001 for each), and both 7E3 and eptifibatide significantly, but incompletely, inhibited the adhesion of T6-activated platelets to D-dimer (P = .01 and P = .03, respectively). In sharp contrast, mAb 10E5 had no impact on T6-induced adhesion of platelets to D-dimer (P = .35), although it dramatically inhibited the binding of nonactivated and activated platelets to fibrinogen. Paradoxically, EDTA enhanced the adhesion of nonactivated platelets to D-dimer (P < .005), which is similar to the effect of EDTA that we previously found with platelet adhesion to D98.8

Adhesion of HEK 293 cells expressing αIIbβ3

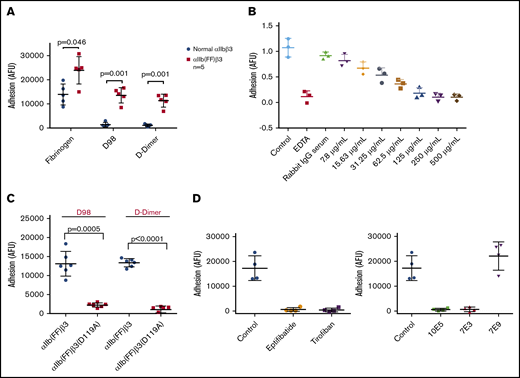

HEK 293 cells expressing normal αIIbβ3 bound well to fibrinogen, but poorly to both D98 and D-dimer (Figure 5A). In contrast, HEK 293 cells expressing the constitutively active αIIb(FF)β3 mutant (HEK-αIIbFFβ3) adhered well to both D98 and D-dimer (Figure 5A). The purified IgG from the pAb to D-dimer inhibited HEK-αIIbFFβ3 cell adhesion in a dose-dependent manner, with concentrations of ∼250 µg/mL reducing the adhesion to the same level as EDTA (Figure 5B). The adhesion of these cells to both D98 and D-dimer was nearly eliminated by the β3 Asp119Ala mutation, which alters the β3 MIDAS region and eliminates normal αIIbβ3-mediated adhesion to fibrinogen8 (Figure 5C). HEK-αIIbFFβ3–mediated cell adhesion to D98 and D-dimer was also markedly reduced by 7E3 (20 μg/mL) and by the small-molecule inhibitors eptifibatide and tirofiban, which bind to the RGD-binding pocket36,45 (Figure 5D). Of note, 10E5 also inhibited adhesion. In sharp contrast, 7E9, which is directed against the γ12 peptide and inhibits normal αIIbβ3-mediated adhesion to fibrinogen,24 did not affect the adhesion (Figure 5D).

Interaction of HEK 293 cells expressing either normal αIIbβ3 or the constitutively active αIIbβ3 mutant αIIb(FF)β3 with fibrinogen, D98, and D-dimer. (A) HEK 293 cells expressing normal αIIbβ3 (normal αIIbβ3) adhered to fibrinogen, but not D98 or D-dimer, whereas HEK 293 cells expressing the constitutively active mutant αIIb(FF)β3 adhered well to D98 and D-dimer in addition to fibrinogen. (B) Inhibition of adhesion of HEK cells expressing αIIbFFβ3 to D-dimer by the polyclonal anti–D-dimer antibody IgG. (C) The Asp119Ala mutation, which disrupts the β3 MIDAS region, inhibited adhesion of HEK cells expressing αIIbFFβ3 to D98 and D-dimer. (D) The small-molecule αIIbβ3 antagonists eptifibatide (100 μM) and tirofiban (10 μM), which bind to the RGD binding pocket, inhibited the adhesion of HEK cells expressing αIIbFFβ3 to D-dimer (P < .001 for all vs control; n = 4), as did the ligand-blocking anti-αIIbβ3 mAbs 10E5 and 7E3 (20 μg/mL for both; P < .001 for both; n = 4), but not the mAb 7E9 directed at the C-terminal region of the fibrinogen γ-chain (P = .25; n = 4).

Interaction of HEK 293 cells expressing either normal αIIbβ3 or the constitutively active αIIbβ3 mutant αIIb(FF)β3 with fibrinogen, D98, and D-dimer. (A) HEK 293 cells expressing normal αIIbβ3 (normal αIIbβ3) adhered to fibrinogen, but not D98 or D-dimer, whereas HEK 293 cells expressing the constitutively active mutant αIIb(FF)β3 adhered well to D98 and D-dimer in addition to fibrinogen. (B) Inhibition of adhesion of HEK cells expressing αIIbFFβ3 to D-dimer by the polyclonal anti–D-dimer antibody IgG. (C) The Asp119Ala mutation, which disrupts the β3 MIDAS region, inhibited adhesion of HEK cells expressing αIIbFFβ3 to D98 and D-dimer. (D) The small-molecule αIIbβ3 antagonists eptifibatide (100 μM) and tirofiban (10 μM), which bind to the RGD binding pocket, inhibited the adhesion of HEK cells expressing αIIbFFβ3 to D-dimer (P < .001 for all vs control; n = 4), as did the ligand-blocking anti-αIIbβ3 mAbs 10E5 and 7E3 (20 μg/mL for both; P < .001 for both; n = 4), but not the mAb 7E9 directed at the C-terminal region of the fibrinogen γ-chain (P = .25; n = 4).

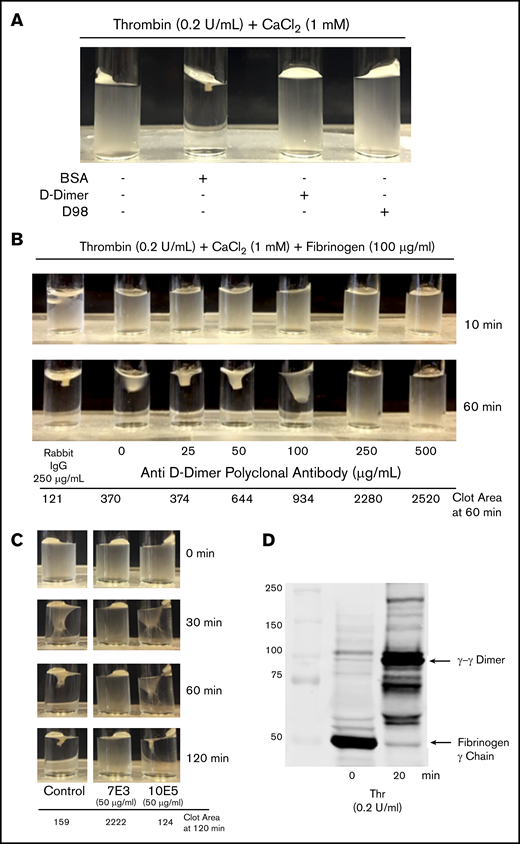

Clot retraction

Incubating washed platelets (3 × 108/mL) with either D98 or D-dimer (200 µg/mL) resulted in dramatic inhibition of clot retraction, whereas incubation with the same amount of BSA did not inhibit clot retraction (Figure 6A). The pAb to D-dimer inhibited clot retraction in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 6B). Because mAb 10E5 did not inhibit T6-induced adhesion of platelets to D-dimer whereas mAb 7E3 inhibited the adhesion, we tested the effects of these antibodies on clot retraction (Figure 6C). There was nearly complete inhibition of clot retraction by 7E3, whereas 10E5 produced only a minor delay observable at 60 minutes and no observable inhibition at 120 minutes. To assess fibrin cross-linking we removed aliquots at time 0 and 20 minutes and used immunoblot analysis to assess the appearance of γ-γ dimers (Figure 6D). Nearly all of the fibrinogen was converted into cross-linked fibrin at the 20 minutes time point.

D-dimer, D98, an anti D-dimer pAb, and mAb 7E3 inhibit clot retraction, but mAb 10E5 does not. (A) Clot retraction in the absence and presence of D-dimer and D98. Washed platelets (3 × 108/mL) were incubated for 20 minutes with 200 μg/mL BSA, D-dimer, or D98 and then added to a glass cuvette containing thrombin (0.2 U/mL) and 1 mM CaCl2. (B) Anti–D-dimer pAb inhibited clot retraction. Washed platelets (3 × 108/mL) were incubated for 10 minutes with the indicated concentration of anti–D-dimer pAb and 100 µg/mL human fibrinogen and then added to a glass cuvette containing 0.2 U/mL thrombin and 1 mM CaCl2. (C) Effect of monoclonal antibodies 7E3 and 10E5 on clot retraction. Clot retraction was performed as indicated in panel A, either in the absence (control; C) or presence of 50 µg/mL of each of the antibodies. The clot area is expressed in square pixels. (D) Immunoblot of the fibrinogen γ-chain at time 0 and 20 minutes of clot retraction. Samples from a control clot retraction experiment were solubilized in sodium dodecyl sulfate and immunoblotted with an antibody to the fibrinogen γ-chain. At 20 minutes, nearly all of the γ-chain had transitioned into γ-γ dimers.

D-dimer, D98, an anti D-dimer pAb, and mAb 7E3 inhibit clot retraction, but mAb 10E5 does not. (A) Clot retraction in the absence and presence of D-dimer and D98. Washed platelets (3 × 108/mL) were incubated for 20 minutes with 200 μg/mL BSA, D-dimer, or D98 and then added to a glass cuvette containing thrombin (0.2 U/mL) and 1 mM CaCl2. (B) Anti–D-dimer pAb inhibited clot retraction. Washed platelets (3 × 108/mL) were incubated for 10 minutes with the indicated concentration of anti–D-dimer pAb and 100 µg/mL human fibrinogen and then added to a glass cuvette containing 0.2 U/mL thrombin and 1 mM CaCl2. (C) Effect of monoclonal antibodies 7E3 and 10E5 on clot retraction. Clot retraction was performed as indicated in panel A, either in the absence (control; C) or presence of 50 µg/mL of each of the antibodies. The clot area is expressed in square pixels. (D) Immunoblot of the fibrinogen γ-chain at time 0 and 20 minutes of clot retraction. Samples from a control clot retraction experiment were solubilized in sodium dodecyl sulfate and immunoblotted with an antibody to the fibrinogen γ-chain. At 20 minutes, nearly all of the γ-chain had transitioned into γ-γ dimers.

Discussion

We recently studied the interaction of αIIbβ3 with fibrinogen fragments D100, which has an intact γ404-411 sequence, and D98, which lacks an intact γ404-411 sequence, to identify sites of interaction between fibrin(ogen) and αIIbβ3 other than that between γ404-411 and the RGD-binding pocket on αIIbβ3.8 We found that (1) nonactivated platelets adhered well to fibrinogen, but not to D98, whereas activated platelets adhered well to immobilized fibrinogen and D98; (2) cells expressing normal αIIbβ3 bound to fibrinogen, but not to D98; and (3) cells expressing constitutively active αIIbβ3 mutants adhered well to immobilized D98. In the present study, to define better the likely mechanisms underlying platelet-fibrin interactions and clot retraction, we extended our studies to the interaction of αIIbβ3 with D-dimer and the role of that interaction in platelet-mediated clot retraction.

Our current data indicate that activation of αIIbβ3 is also required for platelets to interact with D-dimer, but as with the interaction with D98, the interaction is fundamentally different from the interaction between fibrinogen and αIIbβ3, because γ-γ cross-linking makes it impossible for the γ-chain residue Lys406 to interact with the αIIb residue Asp224. That small-molecule αIIbβ3 antagonists that interact with the αIIbβ3 RGD binding pocket and 7E3 (which binds adjacent to the RGD binding pocket on β3)46 dramatically inhibit the interactions of activated αIIbβ3, either recombinant or on platelets, with D-dimer and D98, suggests that the D-dimer binding site either is physically near the RGD binding site or is allosterically altered by changes induced by the αIIbβ3 antagonists. This conclusion is also supported by the inhibition of adhesion to D-dimer of HEK 293 cells expressing activated αIIbβ3 produced by the β3 Asp119Ala mutation that disrupts the MIDAS region in the RGD binding pocket. It is notable that, although both mAb 7E3 and eptifibatide reduced the adhesion of activated platelets to D-dimer to the same level as EDTA (Figure 4), some residual adhesion remained, raising the possibility that this effect is mediated by another αIIbβ3 mechanism of binding and/or other platelet receptors. In either case, this other mechanism, or other receptor(s), also appears to require activation, because there was virtually no platelet adhesion to D-dimer in the absence of activation. The results with 10E5, which binds to the αIIb cap domain,36 are complex. mAb 10E5 inhibited the adhesion of HEK 293 cells expressing the constitutively active αIIb(FF)β3 mutant to D-dimer; it did not inhibit the adhesion of T6-activated platelets to D-dimer, although it inhibited the adhesion of nonactivated and T6-activated platelets to fibrinogen and also inhibits platelet aggregation induced by a variety of agonists, including T6.35 This result raises the possibility that there are subtle differences between the binding to the D-dimer of the constitutively active receptor expressed on HEK 293 cells and the T6-activated receptors on platelets. Thus, the αIIb cap domain may play a more important role with the former than the latter. The inability of 10E5 to inhibit the interaction of T6-activated platelets with D-dimer, despite its inhibition of T6-activated platelets to fibrinogen, further supports differences in binding mechanisms.

One of the differences between fibrinogen and cross-linked fibrin is the potential constraint imposed on the C-terminal region of the fibrinogen γ-chain because of polymerization and γ-γ cross-linking. These changes may create steric obstacles for fibrin to interact with αIIbβ3. When visualized by relatively low-resolution EM, rotary-shadowed D-dimer molecules were reported to appear as oblong structures approximately twice the length (∼20 nm) of D domains.10 Crystal structures of human D-dimer demonstrated 2 different orientations of the abutting D domains, one essentially linear and the other angulated.9 Although the γ-chain cross-link site was not clearly identified, simulated annealing indicated that the cross-link was present only with the angulated orientation, a conclusion supported by the crystal structure of lamprey fibrinogen, which showed 2 similar orientations, and in which the cross-link site was better identified.9 Our negative-stain EM images of the D-dimer extend these studies by demonstrating that D-dimer has considerable flexibility about the cross-link site, making it theoretically possible for this site to interact with the αIIbβ3 headpiece without steric clashes that might be expected if the molecule were rigid. This conclusion is tempered, however, by the recognition that D-dimer also interacts with an E domain in fibrin, and the latter may limit the D-dimer flexibility.47

Even though the γ-γ cross-link renders Lys406 unable to form a salt bridge with αIIb Asp224, it may still allow the γ407-411 peptide to bind to the β3 subunit via coordination of the MIDAS Mg2+ by the Asp410 carboxyl group and via an interaction of Val411 (through an intermediary water molecule) with the ADMIDAS (adjacent to MIDAS) Ca2+6 if the peptide retains sufficient accessibility and flexibility. Kloczewiak et al48 and Lin et al49 previously demonstrated that the γ407-411 sequence peptide can bind to αIIbβ3, inhibit fibrinogen binding, and induce opening of the β3 headpiece, but only at concentrations approximately six- to sevenfold higher than those required for a peptide with the γ400-411 sequence. The potentially increased avidity of the repetitive binding sites in polymerizing fibrin (simulated by the high density of immobilized D-dimer) may compensate for the reduced affinity of the γ407-411 peptide relative to the γ400-411 peptide. This hypothesis implies that the interaction of D-dimer with αIIbβ3 occurs primarily or exclusively with the β3 subunit. This notion may partially explain the paradoxical finding that 10E5, which only interacts with the αIIb subunit, is not able to inhibit the binding of T6-activated platelets to D-dimer. In this case, the finding that 10E5 inhibits the adhesion of the HEK 293 cells expressing activated αIIbβ3 to D-dimer may reflect reduced reorganization of the β3 headpiece compared with T6-activated platelets, with closer proximity of the αIIb subunit to the β3 binding site.

Our finding that platelets and recombinant αIIbβ3 require activation to interact with D-dimer parallels the requirement for platelet activation to support clot retraction. Multiple investigators noted that fibrin clots formed by reptilase, which does not activate platelets, in the presence of platelets do not undergo clot retraction.50-52 In contrast, activating platelets with thrombin (and then neutralizing thrombin’s enzymatic activity), adenosine diphosphate, epinephrine, or collagen before adding them to reptilase-induced fibrin resulted in clot retraction.52 These data are supported by the later finding of Hantgan et al53 that platelets must be activated to support binding to fibrin and clot retraction.

Although αIIbβ3 is essential for clot retraction, the weight of evidence indicates that the interaction is not mediated by interaction of the RGD binding pocket with the fibrinogen γ404-411 peptide. In particular, clot retraction is essentially normal with washed platelets in the presence of fibrinogen lacking the γ408-411 sequence, although the possibility that native fibrinogen released by platelets compensated for the lack of intact added fibrinogen makes these data less than definitive.54,55 Chelating divalent cations with EDTA essentially eliminates the interaction of fibrinogen with the RGD binding pocket, but the effects of EDTA on clot retraction are complex. A requirement for Ca2+ in clot retraction was reported by Budtz-Olsen in 1951,56 and Jelenska and Kopeć57 reported complete inhibition of clot retraction by EDTA in a washed-platelet system in which thrombin was used to initiate clot formation. Carr et al58 subsequently reported, however, that EDTA only partially reduces platelet-mediated clot force development. Separately, Zucker and Grant29 found that incubating citrated-platelet–rich plasma with 5 mM EDTA or EGTA at pH >8 at 37°C for at least 5 minutes results in irreversible loss of platelet aggregation in response to ADP, epinephrine, and the ionophore A23187, even when the samples were recalcified. In contrast, however, they found that incubating platelet-rich plasma with EGTA at a high pH at 37°C did not inhibit clot retraction when the samples were recalcified. Their results were confirmed by White,30 who used EDTA for both platelet-rich plasma and washed platelets. Thus, conditions of cation deprivation that irreversibly alter αIIbβ3 interaction with fibrinogen to support platelet aggregation do not prevent it from interacting with fibrin to support platelet-mediated clot retraction.

There are conflicting data on whether factor XIII activity is necessary for platelet-mediated clot retraction, with studies in patients with factor XIII deficiency showing no impact,59 whereas Kasahara et al4 reported mouse studies in which clot retraction required cross-linked fibrin attachment to a subpopulation of αIIbβ3 receptors in sphingomyelin-rich lipid rafts that connect to actin and Ser19-phosphorylated myosin light chain. Our data on clot retraction indicate that D-dimer is capable of inhibiting clot retraction when thrombin is added to washed platelets, as can a pAb to D-dimer, suggesting that D-dimer can interact with platelet αIIbβ3 at the same site that mediates the interaction with polymerized fibrin or potentially at another site that interferes with the polymerized fibrin binding site. Our experiments relied on the fibrinogen released from platelets, and so the fibrinogen levels were much lower than in plasma, ∼15 µg/mL.60 We chose this system, which we have used previously,44 because we could not easily achieve concentrations of D-dimer equivalent to plasma fibrinogen concentrations of 2 to 4 mg/mL. Thus, our system was not designed to assess the physiologic impact of D-dimer, but rather to establish whether there is competition between polymerizing fibrin and D-dimer for αIIbβ3. We recognize that physiologic levels of D-dimer (<0.5 µg/mL fibrinogen equivalent units) are much lower than those we tested, and even pathologically elevated levels, as reported with pulmonary emboli (rarely above 20 µg/mL) and recently reported in patients with COVID-19, with and without pulmonary emboli (more commonly, >20 µg/mL), are still below the 200 µg/mL we tested.61,62

It is particularly interesting that the pattern of inhibition of clot retraction by 7E3 and 10E5 paralleled their inhibition of the adhesion of T6-activated platelets to D-dimer, with 7E3 producing near complete inhibition and 10E5 producing little or no inhibition. This result is consistent with, but does not establish, that the 2 phenomena share the same mechanism. It also reinforces the possibility that the β3 subunit at or near the MIDAS plays an important role in both phenomena. Previous studies of the effect of 10E5 on clot retraction, clot tension, and clot force have reported a variety of findings, ranging from enhancement, to virtually no inhibition, to significant inhibition, suggesting that subtle differences in the technique used may affect the results.35,58,63,64

In summary, although the interaction of αIIbβ3 with D-dimer differs from that with fibrinogen, it probably involves contributions from regions on β3 that are close to or that are affected by changes in the RGD binding pocket. That both D-dimer and a pAb against D-dimer inhibit clot retraction links our findings to this important biological process, as does the similarity in inhibition patterns using 10E5 and 7E3 and observations by others52,53 that clot retraction requires platelet activation.

For original data, please contact the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported, in part, by National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant HL19278; by Clinical and Translational Science Award program grant UL1 TR001866 from the NIH, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences; and by funds from Stony Brook University.

Authorship

Contribution: L.B. and H.Z. designed, performed, and analyzed the functional experiments and wrote the manuscript; Y.Z. designed, performed, and analyzed the EM experiments; J.L. performed the mutagenesis experiments; T.W. designed, oversaw, and analyzed the EM studies and wrote the manuscript; and B.S.C. designed and oversaw the study, analyzed the data, and had primary responsibility for writing the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: In accordance with federal law and the policies of the Research Foundation of the State University of New York, B.S.C. has royalty interests in abciximab (Centocor), a derivative of mAb 7E3. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Barry S. Coller, Rockefeller University, 1230 York Ave, New York, NY 10065; e-mail: collerb@rockefeller.edu.

References

Author notes

L.B. and H.Z. contributed equally to this study.