Methods for the development of clinical guidelines have advanced dramatically over the past 2 decades to strive for trustworthiness, transparency, user-friendliness, and rigor. The American Society of Hematology (ASH) guidelines on venous thromboembolism (VTE) have followed these advances, together with application of methodological innovations.

In this article, we describe methods and methodological innovations as a model to inform future guideline enterprises by ASH and others to achieve guideline standards. Methodological innovations introduced in the development of the guidelines aim to address current challenges in guideline development.

We followed ASH policy for guideline development, which is based on the Guideline International Network (GIN)-McMaster Guideline Development Checklist and current best practices. Central coordination, specialist working groups, and expert panels were established for the development of 10 VTE guidelines. Methodological guidance resources were developed to guide the process across guidelines panels. A methods advisory group guided the development and implementation of methodological innovations to address emerging challenges and needs.

The complete set of VTE guidelines will include >250 recommendations. Methodological innovations include the use of health-outcome descriptors, online voting with guideline development software, modeling of pathways for diagnostic questions, application of expert evidence, and a template manuscript for publication of ASH guidelines. These methods advance guideline development standards and have already informed other ASH guideline projects.

The development of the ASH VTE guidelines followed rigorous methods and introduced methodological innovations during guideline development, striving for the highest possible level of trustworthiness, transparency, user-friendliness, and rigor.

Introduction

Methods for clinical guideline development have advanced dramatically over the past 2 decades. This is partly a result of increasing demands for trustworthiness, transparency, user-friendliness, and rigor by users and those issuing, approving, and endorsing guidelines.1,2 Contemporary expectations of trustworthy guideline development include the use of systematic reviews as sources of evidence; appropriate involvement of experts, patients, and other stakeholders; and management of conflicts of interest (COIs).

In 2015, the American Society of Hematology (ASH) and the McMaster University GRADE Centre began collaborating on the development of 10 guidelines on venous thromboembolism (VTE) and setting standards for ASH guidelines in a formal guideline effort. For both ASH and the McMaster GRADE Centre, the ultimate aim of the project was to produce guidelines that would be evidence-based, transparent, user-friendly, and optimized for implementation while improving methods for guideline development. ASH has since applied these innovative methods to develop guidelines on other topics (eg, sickle cell disease, immune thrombocytopenia).3-6 The ASH VTE guidelines published to date briefly describe the methods used.7-14 In this article, we describe the methods with more detail, both to document them and to inform future guideline enterprises.

Guideline methodology, results, and experiences

Organization and oversight

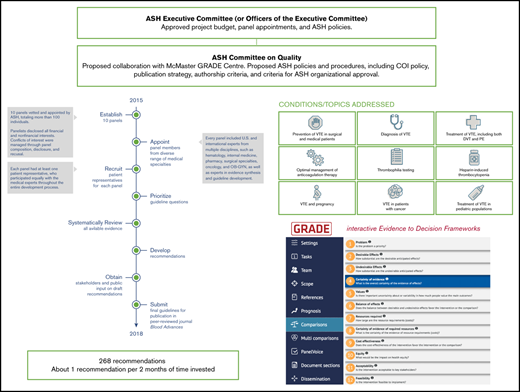

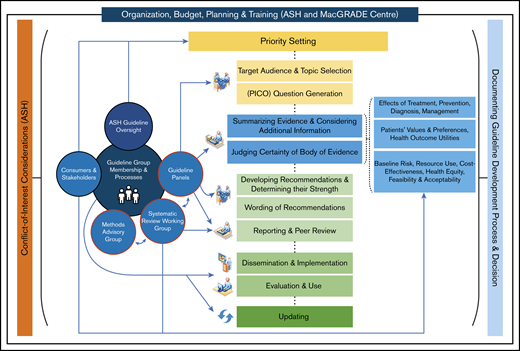

As described by the Guideline International Network (GIN)-McMaster Guideline Development Checklist,15 guideline development involves multiple groups with different roles, whose work requires coordination over multiple steps, which occur both sequentially and iteratively. For the ASH VTE guidelines, Figure 1 illustrates these groups, roles, and steps.

Development process for the ASH VTE guidelines. ASH and the McMaster GRADE Centre collaborated to organize, plan, and coordinate the different steps of the guideline-development process. ASH had primary responsibility for budget, topic selection, guideline panel membership, COI management, public consultation, organizational approval, and dissemination. The Systematic Review Working Group (SRWG) worked with guideline panels to prioritize guideline questions and to synthesize and assess the evidence. Guideline panels formulated recommendations and were responsible for writing the guideline reports. The Methods Advisory Group (MAG) advised on and guided methodology for evidence synthesis, formulation of recommendations, and reporting. PICO, population, intervention, comparisons, and outcomes. Adapted from Schünemann et al15 with permission.

Development process for the ASH VTE guidelines. ASH and the McMaster GRADE Centre collaborated to organize, plan, and coordinate the different steps of the guideline-development process. ASH had primary responsibility for budget, topic selection, guideline panel membership, COI management, public consultation, organizational approval, and dissemination. The Systematic Review Working Group (SRWG) worked with guideline panels to prioritize guideline questions and to synthesize and assess the evidence. Guideline panels formulated recommendations and were responsible for writing the guideline reports. The Methods Advisory Group (MAG) advised on and guided methodology for evidence synthesis, formulation of recommendations, and reporting. PICO, population, intervention, comparisons, and outcomes. Adapted from Schünemann et al15 with permission.

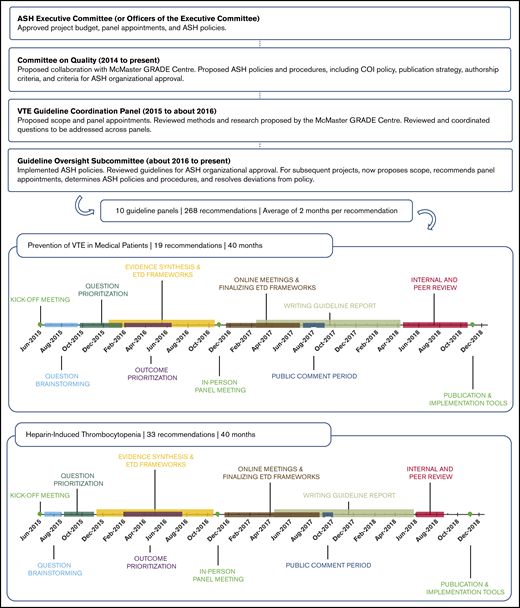

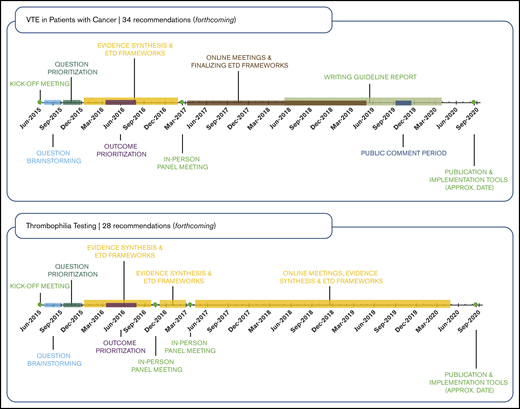

ASH organization and oversight of the project evolved from 2014 to the present, as illustrated by Figure 2. By 2016, appointments to the 10 VTE guideline panels were finalized and the general questions to be addressed by the panels had been proposed by the chairs and coordinated by the VTE Guideline Coordination Panel (see supplemental File 1 for further details).

ASH organization, oversight, and VTE guidelines project timeline. Process and progress of the American Society of Hematology VTE guidelines. In 2014, the ASH Committee on Quality proposed the project as a collaboration with the McMaster GRADE Centre. After approval of the budget by the ASH Executive Committee in May 2014, the Committee on Quality formed an ASH VTE Guideline Coordination Panel in 2015, composed of 11 individuals with expertise in the clinical management of VTE, guideline methodology, or both. The VTE Guideline Coordination Panel prioritized 10 guideline topics on VTE, determined the general scope for each topic, and recommended panel appointments. This work was accomplished via teleconference calls and an in-person meeting held in June 2015, which was also attended by chairs of the 10 guideline panels. Simultaneously, the ASH Committee on Quality proposed ASH policies and procedures relevant to the project, including a COI policy, which were approved by the Executive Committee. The Executive Committee also approved all proposed panel appointments. By 2016, appointments to the 10 VTE guideline panels were finalized, and the general questions to be addressed by the panels had been proposed by the chairs and coordinated by the VTE Guideline Coordination Panel. This panel therefore stopped meeting. Simultaneously in 2016, in response to member demand, the Committee on Quality proposed, and the Executive Committee approved, new guideline projects on other topics, including immune thrombocytopenia and sickle cell disease, as well as collaborative guideline projects with other medical specialty societies. These multiple projects soon demanded more attention than the Committee on Quality could provide. In late 2015, a Guideline Oversight Subcommittee was formed, reporting to the Committee on Quality. Thereafter, the Guideline Oversight Subcommittee assumed responsibility for executing ASH policies and procedures relevant to the VTE guidelines project, including implementation of the ASH COI policy and review of draft guidelines for ASH organizational approval.

ASH organization, oversight, and VTE guidelines project timeline. Process and progress of the American Society of Hematology VTE guidelines. In 2014, the ASH Committee on Quality proposed the project as a collaboration with the McMaster GRADE Centre. After approval of the budget by the ASH Executive Committee in May 2014, the Committee on Quality formed an ASH VTE Guideline Coordination Panel in 2015, composed of 11 individuals with expertise in the clinical management of VTE, guideline methodology, or both. The VTE Guideline Coordination Panel prioritized 10 guideline topics on VTE, determined the general scope for each topic, and recommended panel appointments. This work was accomplished via teleconference calls and an in-person meeting held in June 2015, which was also attended by chairs of the 10 guideline panels. Simultaneously, the ASH Committee on Quality proposed ASH policies and procedures relevant to the project, including a COI policy, which were approved by the Executive Committee. The Executive Committee also approved all proposed panel appointments. By 2016, appointments to the 10 VTE guideline panels were finalized, and the general questions to be addressed by the panels had been proposed by the chairs and coordinated by the VTE Guideline Coordination Panel. This panel therefore stopped meeting. Simultaneously in 2016, in response to member demand, the Committee on Quality proposed, and the Executive Committee approved, new guideline projects on other topics, including immune thrombocytopenia and sickle cell disease, as well as collaborative guideline projects with other medical specialty societies. These multiple projects soon demanded more attention than the Committee on Quality could provide. In late 2015, a Guideline Oversight Subcommittee was formed, reporting to the Committee on Quality. Thereafter, the Guideline Oversight Subcommittee assumed responsibility for executing ASH policies and procedures relevant to the VTE guidelines project, including implementation of the ASH COI policy and review of draft guidelines for ASH organizational approval.

A key feature of the VTE guidelines project was that methods research projects were conducted in parallel with guideline production. At a June 2015 in-person meeting of the VTE Guideline Coordination Panel, researchers from the McMaster GRADE Centre presented a research agenda to the coordination panel and to the chairs of the 10 guideline panels, who provided feedback. The agenda included plans for developing and implementing new methods for prioritization of questions and health outcomes, modeling for decision-making, decision-making in the context of very low-quality evidence, and disseminating recommendations (eg, through patient versions, electronic decision aids) (see Table 1 for additional details).

Work by the McMaster University GRADE Centre was overseen by a principal investigator (H.J.S.) and 2 lead researchers for the project (R.N. and W.W.), hereafter referred to as the McMaster Guideline Coordination Team or, in short, the McMaster team. Their responsibility included determining the overall methodological process including the synthesis of the research evidence, preparation of GRADE Evidence-to-Decision (EtD) frameworks,16,17 and interaction between panels and systematic review teams. A Methods Advisory Group (MAG), which included the methodology chairs and available clinical chairs of the 10 guideline panels, met regularly throughout the project, provided input about methods, and supported coordination and communication across the guidelines.

We also formed a Systematic Review Working Group (SRWG) responsible for leading systematic reviews and developing the EtD frameworks. For the 10 guidelines, 13 systematic review leads with extensive experience in evidence synthesis methodology and the GRADE approach were supported by ∼90 international collaborators with various levels of methodological expertise. Weekly meetings of the SRWG were used for training on methods and process and for sharing examples of work completed for teaching. To ensure consistency across the guidelines, we prepared instructional methodology resources, including documents, videos, and templates. For example, we provided guidance for searching online databases for existing systematic reviews and individual studies, classifying systematic reviews as minor or major updates, managing search alerts, reporting outcomes in GRADE evidence profiles, and preparing EtD frameworks.

Panel selection

Selection criteria for guideline panel membership included expertise (clinical, methodological, or lived experience), as well as geographical location, sex, and COI considerations. Prior to appointment, ASH staff vetted all panelists to ensure that a majority of the panel members did not have COIs. Each panel was led by a clinical chair and a methodology cochair. Most panelists, and all chairs, were clinical experts. In addition, each panel included 1 to 3 methodology experts (including the cochair) and 2 patient representatives. A total of 123 panelists were selected for the 10 guideline panels, with some serving on more than 1 panel. Seventy-four panelists, including all patient representatives, were not ASH members. Clinical experts who were not ASH members were identified by soliciting recommendations from ASH members and from other professional societies.

Patients and caregivers were identified via a variety of methods, including recommendations from clinical experts, recommendations from the Consumers United for Evidence-Based Healthcare (http://consumersunited.org/), and outreach to patient-advocacy organizations (see supplemental File 1 for further details). ASH staff created a 1-page informational announcement explaining the purpose of clinical practice guidelines and the importance of patient representatives in the guideline-development process. Interested individuals were invited to submit a short personal statement about their experience with VTE.

Panel training

The McMaster Guideline Coordination Team prepared a project webpage with training videos and reference documents (see supplemental File 2). These videos explained the overall guideline-development process including, prioritizing questions, rating patient-important outcomes, rating the certainty in the evidence, and formulating recommendations. With ASH staff, members of the ASH VTE Guideline Coordination Panel also prepared videos on the management of COIs, the guideline-approval process, and publication of the guidelines. These materials were shared with all panelists prior to initial panel teleconferences, then reviewed with the panels on the calls. Patient representatives attended an introductory teleconference specifically tailored to including the patient perspective throughout the guideline-development process.

COI management

COIs of all participants were managed according to an ASH-approved COI policy for guideline development (see supplemental File 3). The policy intends to meet recommendations of the Institute of Medicine (IOM) and the Council of Medical Specialty Societies (CMSS).2,18 A COI was defined as an individual having “current material interests outside of ASH that could influence or could be perceived as influencing his/her decisions, actions, or presentations.” Supplemental File 1 describes the criteria that were used for determining the presence of COI. COI meeting the criteria were managed by ASH in 3 main ways: through disclosure, guideline panel composition, and recusal from making specific recommendations.

Disclosure.

Before participation, all guideline panel members and members of the evidence-synthesis team completed a disclosure-of-interests (DOI) form (see supplemental Files 4 and 5). This form collected information about previous (24 months prior) and expected interests focusing on all financial relationships and interests with for-profit health care companies, regardless of possible relevance to the guideline topic. The form also collected declarations of “not mainly financial” or intellectual interests, including previously published opinions, non–industry-funded research, and clinical specialty.

ASH staff and members of the ASH Committee on Quality judged every disclosure and annotated the DOI forms to describe transparently (1) the ASH judgment, that is, whether or not a disclosed interest was a conflict, (2) the rationale for the judgment, and (3) who contributed and signed off on the judgment. The published DOI forms provide judgments by ASH about every disclosure, which often required substantial review and discussion. ASH developed internal documents to help ensure consistent judgments by different ASH staff and members for common situations.

The completed DOI forms were made available to all panel members during the project. At every meeting or teleconference, we reminded guideline panelists of the DOI forms and prompted them to make new disclosures. ASH staff and members reviewed new disclosures, but previously documented disclosures or judgments were never removed or changed. The forms received a final update prior to guideline submission and were included with the published guidelines.

Exclusions from participation in a panel.

Consistent with recommendations of the IOM and CMSS,2,18 each panel was composed so that a majority, including the panel cochairs, during guideline development did not have any current material interest in a for-profit company that could be affected by that panel’s recommendations. Individuals with certain conflicts were considered ineligible for a guideline panel (eg, individuals with equity ownership in or employment with a for-profit company affected by the guidelines). As a result of this rule, 1 individual was asked to resign after initial appointment. Members of the systematic review team with a current, material interest in any affected for-profit health care company did not serve as sole leads for systematic reviews or drafting EtD frameworks. ASH considered declared nonfinancial interests in appointing a balanced, multidisciplinary, and diverse panel, but no individual was excluded from participation on the basis of nonfinancial interests.

Recusal from making (specific) recommendations.

Recusal was also used to manage conflicts, consistent with recommendations of the IOM report on COIs in medical research, education, and practice and GIN principles,19,20 along with an existing 2014 ASH general policy for managing COIs.21

During deliberations, on a question-by-question basis, panel members with a current direct financial interest participated in discussions about the research evidence and clinical context. However, these individuals were recused from making judgments or voting (eg, on the magnitude of desirable health effects) that could influence the direction and strength of the recommendation. ASH staff prepared matrices describing which guideline panelists should be recused for which questions and for what conflicts. Determinations sometimes required substantial review and discussion with clinical experts, for example, to judge the potential impact, whether negative or positive, of a specific recommendation on a specific company. Because of concerns about both actual and perceived bias, determinations tended to be conservative. For example, recusal was required regardless of dollar amount of the conflict and regardless of the relevance of the activity reported (eg, consulting about an unrelated product for an affected company triggered recusal). Recusal was also sometimes required for conflicts with companies that could be indirectly affected by a recommendation. ASH did not require individuals to be recused for indirect financial conflicts (eg, research funding paid to the individual’s institution).

To start the discussion for each guideline question at the in-person panel meetings, panelists referenced the recusal matrix and indicated their recusal status using yellow tent cards. The color yellow was intended to indicate caution around participation rather than total prohibition as just described. Individuals were also allowed to self-recuse for any reason, but this rarely occurred. Occasionally, individuals who were not required to be recused used the yellow tent card candidly to communicate to the guideline panel an important self-perceived conflict such as study leadership or strong opinion.

Question generation and prioritization

ASH’s VTE Guideline Coordination Panel prioritized the 10 VTE guideline topics. Question generation for each guideline followed the population, intervention, comparisons, and outcomes (PICO) framework,22 and began during the June 2015 kickoff meeting with the panel chairs. The chairs brainstormed an initial list of questions for their guidelines. This was followed by discussion among the groups to address any overlap and ensure cohesiveness of the questions across the 10 guidelines (eg, ensuring that if the VTE diagnosis guideline included a specific question, the VTE treatment guideline would include a complementary question). The McMaster team and ASH staff then organized kickoff online teleconferences for each guideline panel to introduce processes and finalize brainstorming and prioritization of their guideline questions.

The McMaster team created a template to prepare “question-brainstorming” online surveys for panel members to suggest any important questions thought to be missing (see supplemental File 6). Subsequently, panel cochairs reviewed survey responses and updated the questions list for prioritization.

In the same fashion, the McMaster team prepared “question prioritization” online surveys for panel members to rate the importance of the questions in the revised list, as well as subtopics where applicable (eg, specific types of surgery for the guideline on prevention of VTE in surgical hospitalized patients) (see supplemental File 7). We implemented an approach that asked panel members to rate each question according to 6 criteria (see Box 1), in addition to a global rating of importance, using a 9-point scale.

Box 1. Criteria to inform prioritization of guideline questions

A question would be considered of priority if it was one:

(i) that commonly arises in practice,

(ii) for which there is uncertainty in practice regarding how to manage patients,

(iii) for which there is new research evidence to consider,

(iv) that is associated with variation in practice,

(v) that has important consequences for, or is associated with, high resource use or costs, or

(vi) that has not been previously or sufficiently addressed (eg, in previous guidelines).

Panel cochairs reviewed mean and median ratings categorized as high priority for the guideline (rating of 7-9), important but not of high priority (rating of 4-6), or of low priority (rating of 1-3). Each panel discussed its survey results in teleconferences to reach a consensus on the final list of questions. We aimed to include ∼20 questions for each guideline, which could be answered in reasonable time frames in this first iteration of the ASH VTE guidelines. After discussions, panel members completed an online agreement survey to sign-off on the final list of questions. Finally, the cochairs of the VTE Guideline Coordination Panel (A.C. and H.J.S.) reviewed the prioritized question lists for the 10 guidelines in a question-mapping exercise to identify any overlap and ensure cohesiveness across the guidelines.23 For example, questions relating to prophylaxis for VTE in ambulatory patients with cancer were covered in the guideline on VTE in cancer, not in the guideline on VTE prevention in medical patients. The panels prioritized questions resulting in 10 to 34 recommendations formulated per guideline, for a total of 268 recommendations covering VTE prevention, diagnosis, and management (see Figure 2).

Prioritization of outcomes and outcome utility rating

The question-brainstorming surveys in the preceding step also included a list of potential patient-important outcomes identified by the cochairs and sought panel suggestions on any other relevant outcomes. The McMaster team prepared online outcome prioritization surveys for panel members to rate the importance of the outcomes brainstormed by all panels (see supplemental File 8). Because some patient-important outcomes, for example, pulmonary embolism (PE), deep vein thrombosis (DVT), and major bleeding, overlapped across most questions, we did not rate outcome importance by individual questions.

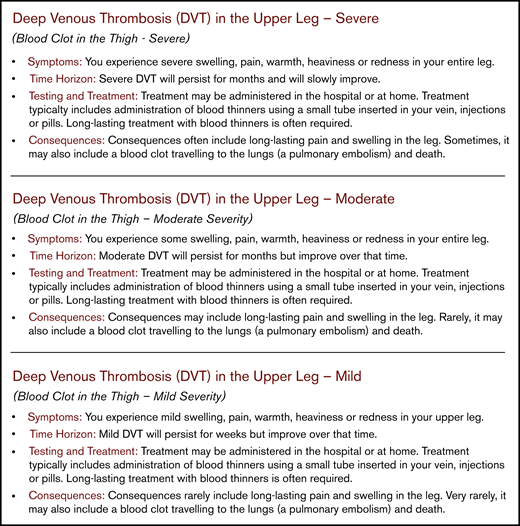

Patient-important outcomes may be categorized according to their location (eg, proximal or distal DVT), presentation (symptomatic or screening-detected DVT), or severity (eg, mild or severe DVT). To ensure that panel members envisioned the same outcome when discussing the evidence, we developed health-outcome descriptors (also referred to as health marker states) to create common definitions that described the outcomes with respect to symptoms, time horizon, testing and treatment, and consequences (see Figure 3).24,25 We developed 127 health-outcome descriptors for outcomes brainstormed by the panels; 18 of the outcomes were described with 2 (eg, nonsevere vs severe) or 3 levels (eg, mild, moderate, or severe) of severity.

Example health-outcome descriptors for proximal DVT. Pairs of methodological and clinical experts from the panels drafted the descriptors to create common definitions for outcomes with respect to symptoms, time horizon, testing and treatment, and consequences. The health-outcome descriptors serve to differentiate outcomes with respect to consequences and severity for patients, and aid in making decisions about desirable and undesirable health effects (available at https://ms.gradepro.org/).

Example health-outcome descriptors for proximal DVT. Pairs of methodological and clinical experts from the panels drafted the descriptors to create common definitions for outcomes with respect to symptoms, time horizon, testing and treatment, and consequences. The health-outcome descriptors serve to differentiate outcomes with respect to consequences and severity for patients, and aid in making decisions about desirable and undesirable health effects (available at https://ms.gradepro.org/).

According to the GRADE approach, panel members rated the importance of the outcomes for decision-making on a 9-point scale: 1 to 3 as limited or no importance; 4 to 6 as important, but not critical; and 7 to 9 as critical.22 We shared the survey results with the panels and held online teleconferences to reach consensus through discussion on the final outcomes to be considered per question.

Additionally, the McMaster team developed and administered an outcome utility rating survey for all prioritized outcomes across the guidelines. We used the health-outcome descriptors and asked panel members to rate the health utility of outcomes on a scale of 0 (representing the state of being dead) to 100 (representing the state of full health).25-29 The results of the panel surveys were used to supplement, where needed, the research evidence from a systematic review of patients’ values and preferences to aid the panels in determining the relative importance of health outcomes in the EtD frameworks. For example, although the systematic review–provided utility values for outcomes, such as PE, DVT, and obstetrical bleed, help assess the relative value patients place on these outcomes, no utility data were identified for outcomes such as heparin-associated osteoporotic fractures. In this instance, the utility rating survey result was provided in the EtD framework to inform the panel’s discussion on use of heparin for pregnant women with acute VTE.

Summarizing the evidence and judging certainty in the body of evidence

We conducted new systematic reviews or updated existing systematic reviews for each question following Cochrane methods.30 We evaluated the risk of bias in existing reviews using elements of the ROBIS tool.31 We classified potentially eligible reviews as requiring minor or major updates based on criteria described previously (see supplemental File 9 for definitions).32 The 268 recommendations were informed by 219 systematic reviews across the 10 guidelines. Of these, 31 required a minor update of an existing systematic review, 104 required a major update, and 84 required a new review. Common reasons for requiring major updates or new reviews included the population or outcomes not fully matching the prioritized questions, and existing systematic reviews not having certainty-in-the-evidence assessments or forest plots from meta-analyses.

To identify existing systematic reviews, members of the SRWG, with the assistance of a research librarian, developed search blocks for Medline, Embase, and Cochrane Library databases. These search blocks were combined into search strategies for specific guideline questions (eg, heparin AND “VTE prophylaxis” AND [systematic review filter]) for each of the 10 guidelines, thereby standardizing the searches. We created ∼250 search blocks that covered the content of the prioritized questions. This helped to increase efficiency in the evidence-synthesis process as it allowed systematic review group members to build search strategies from the blocks for their specific guideline questions.

For updating of existing systematic reviews, we used published search strategies when available; for new reviews, we constructed search strategies using the developed search blocks with study design filters (eg, randomized controlled trial [RCT] filter). Search strategies were published with the guidelines. We searched for nonrandomized studies when RCT evidence was lacking or deemed insufficient through panel discussion. Systematic review leads liaised with content experts from the guideline panels to optimize the process (eg, identifying alternate labels for anticoagulants, identifying questions with scarce RCT evidence, confirming study inclusion). We maintained search alerts to ensure that literature searches remained up-to-date and asked panel members to monitor and inform about new and upcoming publications. We piloted and followed the living systematic review model in updating several of the reviews.33-35

For each question, the SRWG synthesized evidence on intervention effects for the outcomes through meta-analyses, or narratively, and created a GRADE evidence profile using the GRADEpro app (www.gradepro.org).36,37 For questions on diagnosis, the SRWG modeled diagnostic test accuracy and the expected patient-important outcomes of diagnostic pathways developed by the panel.11,12 We assessed risk of bias of individual studies using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool for RCTs, the ROBINS-I tool for nonrandomized studies, or QUADAS-II for test accuracy studies,38-40 and judged the overall certainty in the body of evidence according to the GRADE approach.41 Panels provided systematic review leads with content expertise, for example for rating directness of evidence, or applicability of baseline risk data. Additionally, we identified or conducted systematic reviews for the other criteria in the EtD frameworks, including baseline risks, patients’ values and preferences,42 resource use and cost-effectiveness, impact on health equity, feasibility, and acceptability of interventions. The McMaster team created a template with standardized paragraphs for systematic review leads to follow to summarize this information in the EtD frameworks. For guideline questions without published evidence about the effects of interventions, we surveyed panel members to obtain expert evidence.43 This information was summarized by the SRWG in the EtD frameworks for the guideline panel to deliberate on the desirable and undesirable consequences of the interventions.

Developing recommendations and determining their strength

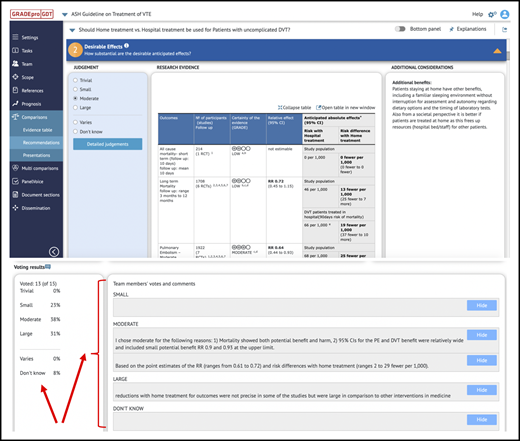

Guideline panels met during preparatory teleconferences prior to in-person panel meetings to review and provide input about the systematic reviews and draft evidence profiles and EtD frameworks. We used the PanelVoice app with GRADEpro to allow panel members to vote on judgments and submit comments for the draft EtD frameworks.37 Summaries of voting and comments were made available to panel cochairs for planning the panel discussion based on EtD frameworks. For example, PanelVoice facilitates identification of disagreement and focus on EtD criteria to develop consensus when judgments of panel members differ in important ways (see Figure 4).

Use of PanelVoice for online voting. Use of the PanelVoice app in GRADEpro allowed us to obtain input from panel members and prevoting on judgements for the EtD frameworks. Prevoting ahead of in-person panel meetings helped to identify areas of agreement and highlight criteria for more in-depth discussion with the panel. As some panels required additional online meetings after their in-person panel meetings to complete recommendations, use of PanelVoice also allowed us to obtain input prior to discussions and agreement on draft recommendations to optimize efficiency. Panel members were able to provide input and agree on recommendations through the PanelVoice surveys, including those who were unable to attend certain online meetings. CI, confidence interval; RR, relative risk.

Use of PanelVoice for online voting. Use of the PanelVoice app in GRADEpro allowed us to obtain input from panel members and prevoting on judgements for the EtD frameworks. Prevoting ahead of in-person panel meetings helped to identify areas of agreement and highlight criteria for more in-depth discussion with the panel. As some panels required additional online meetings after their in-person panel meetings to complete recommendations, use of PanelVoice also allowed us to obtain input prior to discussions and agreement on draft recommendations to optimize efficiency. Panel members were able to provide input and agree on recommendations through the PanelVoice surveys, including those who were unable to attend certain online meetings. CI, confidence interval; RR, relative risk.

Each panel held a 2-day in-person meeting at ASH headquarters to formulate recommendations. In preparation for the meetings, we shared orientation packages with the panel cochairs and members that included the Checklist for Guideline Panel Chairs,44 the Guideline Participant Tool,45 and a quick reference guide for understanding GRADE certainty of evidence and the EtD criteria. Using the EtD frameworks, the panel cochairs led panel members to make judgments and agree on the strength of recommendation (strong or conditional) for each guideline question. Factors considered when rating the strength of recommendation included the priority of the problem, benefits and harms, patients’ values and preferences, resource use and cost-effectiveness, impact on health equity, feasibility, and acceptability.17,46,47 This involved consensus methods and voting if necessary according to predefined rules, whereby a majority vote of 80% or more was required to issue a strong recommendation.

Panels worded recommendations based on a structured template (ie, “The ASH guideline panel recommends/suggests using intervention A over intervention B for patients with X condition/characteristic. Strong/conditional recommendation based on high/moderate/low/very low certainty in the evidence of effects”). Recommendations were supported by explanatory remarks when deemed necessary, justification statements, implementation considerations, considerations for monitoring and evaluation, and identification of research priorities.17 Where deemed necessary, guideline panels also formulated best practice statements according to GRADE guidance.48,49 Until publication, all information was to be kept confidential by panel members and their membership was not publicized.

During the meetings, the cochairs were supported by 1 of the systematic review leads to record key decisions, and they suggested revisions for the guideline content. Additional note-takers from the SRWG recorded the panel discussion and decisions for the EtD criteria in a shared online document. We also video-recorded the panel meetings, with permission from the panelists (eg, to refer back to the discussions during the preparation of the manuscripts). Panel cochairs could attend and observe panels of other VTE guidelines to help with applying consistent approaches to their own meetings at a later date.

Use of the GRADE EtD frameworks and GRADEpro software allowed us to document all decisions and discussions in real time and display them to the panelists during the meetings. If groups did not complete all recommendations for their prioritized questions during the in-person panel meetings, they continued the work by online teleconference, using GRADEpro PanelVoice voting to finalize recommendations.

Public consultation and stakeholder feedback

We sought stakeholder feedback for each guideline by posting draft recommendations and completing EtD frameworks online, and having a 4- to 6-week public comment period (see supplemental File 10). Panels discussed the results and comments in online teleconferences. It was established a priori that public comments would not influence the direction or strength of a recommendation, unless obvious errors were made, but could serve to inform revisions for clarity and understanding by guideline users.

The comments did not result in changes to the direction or strength of recommendations in any of the guidelines. However, they allowed for refinements in wording, addition of clarifications, reordering of recommendations to align with order of interventions in practice, as well as additional justifications of how the panels arrived at the recommendations and how to implement them.

Reporting and peer review

Panel chairs and systematic review leads drafted manuscripts using a standardized template developed for the guidelines (R.N., W.W., J. Brozek, N.S., R.K., P.D., I.N., P.A.-C., A.I., S.K.V., B.R., R.A.M., D.R.A., M.C., T.L.O., D.M.W., G.H.L., S.M., P.M., S.M.B., W.L., A.C., and H.J.S., manuscript in preparation) to facilitate ease of reading by target users and meet guideline reporting criteria (supplemental File 11).50,51 For each guideline recommendation, we summarized the available research evidence on benefits and harms, certainty in the evidence of effects, other EtD criteria, and conclusions and research needs. The completed EtD frameworks with evidence profiles including results of the evidence syntheses allowed authors to have immediate access to all necessary content related to the recommendations. After review by the entire panel, the guideline manuscript was submitted for review and approval by the ASH Guideline Oversight Subcommittee, the ASH Committee on Quality, and ASH Officers. Upon approval, the guidelines were submitted to Blood Advances for peer review.

Dissemination and updating

In addition to the scientific publications in Blood Advances, we published the recommendations in the ASH Clinical Practice Guidelines mobile app, and prepared online versions of the recommendations, EtDs and evidence profiles in the Database of GRADE Guidelines (directly linked to in the guideline manuscripts for each recommendation: https://gradepro.org/guidelines/).24 We prepared patient versions of selected recommendations, disseminated through the ASH Web site (https://www.hematology.org/VTE/) and the annual ASH conference. Teaching slides to complement the guidelines were also developed and made available on the Web site. ASH will maintain the guidelines through monitoring for new evidence, review by experts, and plans for regular revisions according to ASH standard operating procedures for the development of practice guidelines. ASH and the McMaster GRADE Centre are now collaborating on a pilot project to maintain the guidelines through regular updates, including living recommendations.

Discussion

Development of the ASH VTE guidelines followed and pioneered methodological advances in guideline development to achieve a high level of trustworthiness and transparency, while striving for optimal user-friendliness and dissemination. The guideline development considered all 18 domains of the GIN-McMaster Guideline Development Checklist. For several of the domains, we applied novel methods, which can serve as a model for future ASH and other guidelines. Novel methods included centralized training for panel members, a structured approach to coordination of panels working in parallel, a standardized approach to question prioritization, rating of importance of health outcomes with the use of health-outcome descriptors, online voting for EtD frameworks, use of expert evidence in areas with very low-quality evidence, and development of a standardized template for drafting guideline manuscripts (see Table 1).

Strengths

The diversity of the panels, including sex, geographic area, and expertise, is a strength. Furthermore, the structured approach to coordination, as well as designated roles for the coordinating methodologists, panel chair, methodology cochair, and systematic review team leads, worked to achieve consistency in the concurrent production of the 10 guidelines. Regular meetings with the MAG and SRWG allowed for centralized decision-making about methodology and process, which was passed down to the panels and systematic review leads. The designated role of systematic review leads ensured that all chairs had a direct point of contact from the systematic review team throughout the process.

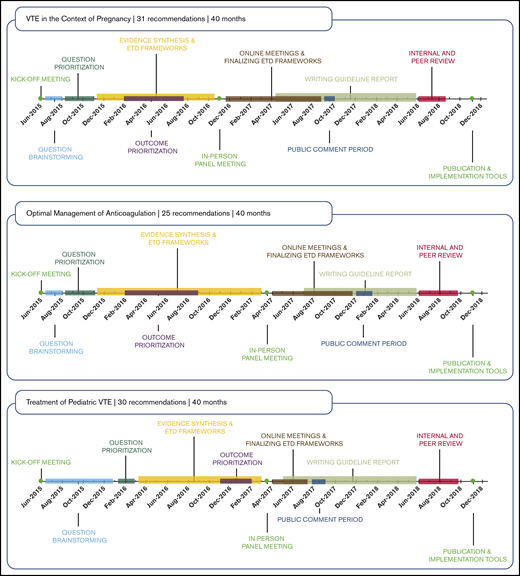

The development and application of methodology guidance documents and templates for completing the guideline-development steps allowed the working groups to achieve a similar rigor across all guideline questions addressed. These also led to improved efficiency in the process, which in turn improved the feasibility of conducting or updating systematic reviews for all guideline questions. Each guideline recommendation was supported by a systematic review of the effects of interventions, including use of indirect evidence or systematically collected expert evidence in areas in which published evidence was insufficient. We additionally conducted systematic reviews to summarize the research evidence for other criteria considered in the EtD frameworks. The EtD frameworks also allowed for consistency in the panels’ approach to decision-making and formulating recommendations regardless of the research evidence available (eg, RCTs with meta-analysis, observational data, expert evidence). Figure 2 shows that the work by the 10 panels proceeded on different timelines. Six panels completed 148 recommendations in ∼40 months, beginning with a June 2015 kickoff meeting and concluding with publication of the guidelines in Blood Advances in November 2018. As a measure of value and time, each of these 148 recommendations required only 1.6 months of invested time by ASH, the McMaster GRADE Centre, and volunteers, including all steps from question formulation to guideline publication. From one-third to one-half of the total time invested was for manuscript development, organizational approval, and journal publication steps. Innovations to make these and other steps more efficient could improve the value of the guideline process, including by making it possible to issue rapid guidelines or rapid recommendations on specific questions with which the required time compares favorably.52

Four other panels required additional time to complete recommendations and publish guidelines. Considering the known and expected publication dates (1 in December 2019, 1 in June 2020, and 2 in December 2020), the 120 total recommendations of these 4 guidelines will have required 2 months of invested time for all steps from question formulation to guideline publication.

In addition, we applied a rigorous and explicit COI management approach according to ASH policy. The approach ensured that all guideline chairs and the majority of each panel did not have any relevant COIs for their guideline. Furthermore, management of COIs on a per-question basis permitting the full participation of all panel members in the discussion about research evidence made the most of the available expertise of the panelists, while preventing potential conflicts from influencing recommendations.

Limitations and learnings

Our work also has several limitations. Foremost, although we believe that the benefits of our process include consistency, rigor, improvement in feasibility, streamlined processes, and reduced resources, we have not formally studied these aspects. As we began the guideline project with online-only meetings of the panels, we required several teleconferences for each group to complete the guideline question and health-outcome prioritization steps. Sufficient time spent on these initial steps was required to prevent downstream issues. If feasible, to finalize question and outcome prioritization, an initial in-person meeting with the full panel, rather than chairs only, might increase efficiency.

Similarly, online teleconferences after in-person panel meetings to complete outstanding recommendations required additional time spread over several months. During this time, we monitored the literature to ensure that evidence syntheses would remain up-to-date; holding a longer in-person panel meeting might be an improvement. In 1 example, while completing the guideline, we were required to add a new guideline question on treatment of VTE with direct-acting oral anticoagulants in patients with cancer as new important trials were published. Publication of small informative recommendation units as a method for more rapid dissemination of completed recommendations could allow for publication of available recommendations while completing remaining work for a large guideline.52-54 The methodology applied to the development of the guidelines also required expertise in guideline development, coordination, and evidence synthesis. We addressed this in our guidelines by recruiting a large team of international collaborators.

Five of the 20 patient representatives dropped off of their panels before the guidelines were complete. Some patients stopped participating due to the long-time commitment, whereas others did not provide a rationale. Throughout the development process, some patient representatives were more engaged than others and maintaining patient engagement throughout a highly technical process remains a challenge. Considerations for improvement include changing the evaluation criteria for patient representatives, creating more resources for patients on the panel, and shortening the length to completion. These ASH VTE guidelines were the first in ASH’s strategic plan to greatly expand society-supported development of trustworthy guidelines. They set the stage for the overall methods that ASH is using now for other guidelines while continuously incorporating lessons learned. These changes included realizing that it is helpful, if feasible, to hold in-person meetings with all panel members at the beginning of each guideline group project; assigning experts to work more closely with the systematic review team as is done in other guidelines; meeting more frequently online with guideline panels; using the health-outcome descriptors, which are available in a database (https://ms.gradepro.org/); updating the COI policy; creating the ASH guideline oversight subcommittee; training of staff at ASH that allows support of guideline projects; and many other innovations.

Implications for the development of ASH and other guidelines

Our approach to the development of the ASH guidelines is applicable to both large-scale and smaller-scale guideline development. We have demonstrated the feasibility of producing evidence-based recommendations, supported by full systematic reviews of intervention effects as well as additional information necessary for decision-making. Through use of templates to facilitate the work and centralize coordination, developers can maintain rigor and consistency in their processes. Use of available guideline-development tools and software can help streamline and partially automate guideline production from the prioritization to implementation steps. Although in-person panel meetings provide the necessary environment for facilitating panel discussion and interacting to formulate recommendations, online work with a panel that has established a group process and norms can help reduce the need for resource-intensive, multiple in-person meetings. Finally, use of GRADE EtD frameworks ensures transparency in the formulation of recommendations, standardization in the development and reporting of recommendations, and adherence to COI policies to achieve consistency and trustworthiness within and across the guidelines. The next steps include decisions about the criteria that should be used for updating the systematic reviews and recommendations; tools such as Check-Up or those implemented by other organizations related to systematic reviews can be used.55,56 ASH is also initiating a pilot project for living recommendations that includes 2 recommendations from these VTE guidelines. The evaluation of that project will support decisions about whether or not producing living recommendations will be feasible.

Data-sharing requests may be e-mailed to the corresponding author, Holger J. Schünemann, at schuneh@mcmaster.ca.

Acknowledgments

The ASH Committee on Quality and the ASH Guideline Oversight Subcommittee provided oversight, for ASH, of the VTE guidelines project across several years. The authors thank those committees and members for contributing to review and refinement of the ASH processes described in this article. The authors also thank members of the VTE Guideline Coordination panel for similar contributions.

Authorship

Contribution: All authors contributed to the review of, and critical revisions to, the manuscript; W.W. wrote the first draft of the manuscript and revised the manuscript based on the authors’ suggestions; H.J.S. contributed sections to the first draft, revisions of subsequent drafts, and the revision after peer review; R.N. and A.C. contributed revisions to subsequent drafts; and R.K. and K.E.A. contributed to drafting and verifying details about ASH processes, organizational oversight, and policies.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.C. has served as a consultant for Synergy and CRO, and received institutional research support on his behalf from Alexion, Bayer, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Sanofi, Spark, and Takeda. A.R. has served on an advisory board for Alexion, Baxter, Bayer, Kedrion Biopharma, and Octapharma Plasma, and has received institutional research support on her behalf from Alnylam (Sanofi Genzyme), Baxalta (Shire), Biomarin, Dimensions Therapeutics, Genetech, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and Roche. D.M.W. has served as a consultant for, and received institutional research support on his behalf from, Roche Diagnostics. E.A.A. has served as a guideline methodologist on other guidelines related to VTE, and has led a number of systematic reviews on VTE. G.H.L. is a principal investigator on a research grant from Amgen to the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, and has consulted within the past 2 years for the following companies on other topics: Biotheranostics, Beyond Spring, G1 Therapeutics, Invitae, Mylan, Partners Therapeutics, Samsung, and Spectrum. H.J.S. was cochair of the ASH VTE guidelines and is cochair of the GRADE Working Group; has developed methods, tools, and approaches for guideline development; has coauthored the background papers for the IOM report on trustworthy guidelines, the GIN-McMaster guideline development checklist, and other tools; is a consultant to ministries of health, the World Health Organization, and professional societies on guideline methodology; and is director of Cochrane Canada (Cochrane methods have served for this guideline). R.K. and K.E.A. are employed by ASH, which has funded and disseminated the guidelines discussed in this paper. S.M.B. reports honoraria from Leo Pharma. S.M. reports research grants and honoraria from Aspen, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb–Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, Pfizer, Portola, and Sanofi; all fees were paid to the author’s institution. T.L.O. has served as a consultant for Instrumentation Laboratory, and has received institutional research support on his behalf from Instrumentation Laboratory, Siemens, Stago, the National Institutes of Health, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Holger J. Schünemann, Michael G DeGroote Cochrane Canada and McMaster GRADE Centres, Department of Health Research Methods, Evidence and Impact, McMaster University, HSC-2C, 1280 Main St West, Hamilton, ON L8N 3Z5, Canada; e-mail: schuneh@mcmaster.ca.

References

Author notes

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.