Key Points

Tumor-specific T-cell immune response to antigen PRAME increases after treatment for pediatric high-risk HL.

Immunosuppressive cytokines decrease after treatment, potentially influencing future addition of immunotherapy for pediatric HL.

Visual Abstract

There is an unmet need to examine antitumor immune responses and predictive biomarkers in the peripheral blood to guide effective combination immunotherapies in classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL). We sought to evaluate T-cell specific immune responses as well as cytokine and chemokine profiles including levels of soluble CD30 (sCD30), sCD163, and thymus and activation-regulated chemokine (TARC) in relation to event-free survival in patients with cHL. The Children’s Oncology Group (COG) clinical trial AHOD1331 was a randomized phase 3 trial for patients with newly diagnosed high-risk cHL, aged 2 to 21 years, which compared standard chemotherapy and doxorubicin, bleomycin, vincristine, etoposide, prednisone, and cyclophosphamide (ABVE-PC) with brentuximab vedotin (Bv) and AVE-PC with response adapted radiation. Our results demonstrate that chemotherapy with or without addition of anti-CD30 antibody-drug conjugate Bv is associated with a favorable cytokine environment for cellular and immunotherapies. Treatment of cHL on both arms increased tumor antigen-specific T-cell responses and resulted in decreased levels of sCD30, sCD163, and TARC. We demonstrate that treatment of cHL on COG AHOD1331 produced an environment that favors antitumor immune response, which may aid in application of further cellular and immunotherapies targeting cHL. This trial was registered at www.ClinicalTrials.gov as #NCT02166463.

Introduction

Risk stratified approaches and response adapted therapy have led to significant improvements in long-term outcomes for pediatric patients with Hodgkin lymphoma (HL).1 Identification of patients who may benefit from targeted immunotherapy or cellular therapy may decrease risks of relapse and complications of chemotherapy and radiation. The Children’s Oncology Group (COG) trial AHOD1331 evaluated the addition of brentuximab vedotin (Bv) to standard chemotherapy in an open-label, multicenter, randomized phase 3 trial for pediatric patients with high-risk classical HL (cHL).2 Bv is an antibody-drug conjugate that targets CD30 on Hodgkin Reed-Sternberg (HRS) cells. Brentuximab consists of an anti-CD30 monoclonal antibody conjugated to microtubule-targeting agent monomethyl auristatin E.3,4 Previous studies have demonstrated that CD30 can activate both NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways. Therefore, Bv likely not only targets HRS cells directly but can also inhibit downstream signaling pathways.5 Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that CD30 plays a role in the tumor microenvironment (TME) by shifting numbers of T helper 1 vs T helper 2 cells as well as upregulating cytokine secretion.5-7 In this follow-up correlative biology study we sought to determine whether targeting CD30 contributes to the restoration of favorable antitumor immune responses in patients with high-risk cHL.

cHL is an inflammatory tumor characterized pathologically by the presence of HRS cells. The highly immune suppressive TME surrounding the HRS cells, including variety of chemokines and cytokines, facilitates avoidance of immune recognition.8,9 For example, natural killer cell and cytotoxic T lymphocyte function is suppressed by a decrease in granzyme B and perforin whereas additional immune cells are recruited by the secretion of chemokines.5 Interaction of CD30 with the CD30 ligand plays a significant role in these interactions in the TME, and inclusion of Bv into the treatment regimen to directly target CD30 may have a more profound effect on these changes in the TME compared with chemotherapy alone. Therefore, distinguishing levels of these cytokines and chemokines including changes before vs after treatment could potentially predict treatment response to chemotherapy with the addition of Bv. Identifying biomarkers in the immune milieu of patients can then further guide effective immunotherapies in cHL. Moreover, adoptive transfer of tumor-associated antigen (TAA)–specific T cells has been deemed safe in relapsed/refractory (R/R) HL.10,11 However, expression of these antigens and a more detailed knowledge of the preservation or restoration of the tumor-specific T-cell response with the addition of Bv, may aid in further optimization of such cellular therapy approaches for cHL.

The objective of this study was to evaluate cHL antigen-specific T-cell responses and levels of CD30, cytokines, and chemokines in patients with advanced-stage cHL who received standard chemotherapy with and without Bv. Previous data suggested that levels of thymus and activation-regulated chemokine (TARC), soluble CD30 (sCD30), and sCD163 may correlate with response but this had not been evaluated in patients receiving chemotherapy regimens with Bv.12-19 Hence, our goals were to (1) identify whether Bv aided in antigen-specific T-cell effector function, which could potentially support the development of next-generation cell therapies for HL,10,20,21 and (2) identify potential biomarkers of response to therapy.

Methods

Trial enrollment

COG AHOD1331 (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT 02166463) was an open-label, phase 3 trial comparing BV-AVEPC (Bv plus doxorubicin, vincristine, etoposide, prednisone, and cyclophosphamide) with standard bleomycin-containing chemotherapy regimen (ABVE-PC) in children and adolescents with high-risk cHL. Radiotherapy was administered to large mediastinal masses and slow early responding sites of involvement. Children and adolescents aged 2 to 21 years with newly diagnosed cHL of Ann Arbor stage IIB with bulk tumor or stage IIIB, IVA, or IVB were eligible for enrollment. Bulk tumor was defined as either a large mediastinal mass or an extramediastinal mass (continuous nodal aggregate, >6 cm). The primary end point was event-free survival (EFS), defined as the time from randomization to the earliest of disease relapse or progression, second malignancy, or death due to any cause.2

A total of 600 patients were enrolled at 153 COG institutions in North America, with a total of 587 eligible patients.2 Peripheral blood samples were collected before initiating treatment as well as after chemotherapy and after radiation, if the patient received radiation. Characteristics of patients at baseline were balanced between the Bv-based regimen and the standard regimen. Clinical trial results have been reported elsewhere.2

COG clinical trial AHOD1331 was approved through National Cancer Institute central institutional review board, with initial approval 11 September 2014.

Sample collection

Peripheral blood samples were collected prospectively before treatment and after chemotherapy and radiation (as applicable) and shipped to a central location for processing. Samples were separated using Ficoll and plasma was isolated, aliquoted, and stored at −80°C until batched analysis.

Tumor antigen T-cell expansion

T cells specific for tumor antigens were expanded from peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patient samples obtained before and after treatment. Mature dendritic cells generated by adherence were pulsed with overlapping peptide pools (PepMix, JPT Peptide Technologies, Berlin, Germany) of tumor antigens preferentially expressed antigen of melanoma (PRAME), survivin, and melanoma-associated antigen 4 (MAGE-A4), and used as antigen-presenting cells to expand antigen-specific T cells, as previously described.20 PRAME, survivin, and MAGE-A4 were chosen as antigens frequently present on lymphoma to evaluate lymphoma-specific T-cell response.22 Nonadherent cells were cocultured with irradiated dendritic cells (25 Gy) in cell media and supplemented with exogenous cytokines.20 A second T-cell stimulation was carried out using irradiated phytohemagglutinin (PHA) blasts as antigen-presenting cells. One week later, the expanded T cells were then harvested for characterization.

T-cell antigen specificity

T-cell specificity for PRAME, survivin, and MAGE-A4 PepMixes were evaluated using anti–interferon gamma (IFN-γ) enzyme-linked immunospot in duplicate. Cells were plated at 100 000 cells per well with PRAME, survivin, and MAGE-A4 PepMixes (200 ng per well) in respective wells, actin PepMix as a negative control, and staphylococcal enterotoxin B (a superantigen) as a positive control. Spot forming cells (SFCs) were read and counted by Zellnet Consulting (Fort Lee, NJ).

Plasma chemokine and cytokine evaluation

Plasma aliquots were thawed on ice followed by centrifugation at 1000g for 10 minutes at 4°C. A human inflammation magnetic bead panel detecting CD30 and CD163, and chemokine magnetic bead panel measuring TARC, was performed on the Luminex multiplex immunoassay system according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Data were analyzed on Luminex-Magpix software. Cytokine levels (interleukin-1β [IL-1β], IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-10, IL-13, IL-15, IL-17a, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, IFN-γ, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1α, MIP-1β, tumor necrosis factor α) were evaluated with the 17-plex multiplex assay (Bio-Rad) and relevant cytokines reported. All samples were run in duplicate.

Statistical analysis

Included patients were selected based on the availability of both pretherapy and posttherapy samples, and all data were current as of the data-freeze date, 30 June 2024. Patient and disease characteristics were reported descriptively and compared between analyzed and excluded cohorts using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables, and χ2 or Fisher exact tests for categorical variables, to ensure features of the studied cohort sufficiently represented all patients from AHOD1331. Among those analyzed for biomarkers, baseline, posttreatment, and change from baseline values were compared by study arm, and paired Wilcoxon tests were used to test whether markers were significantly changed from baseline to end of therapy. Cox proportional hazards regression models with nested restricted cubic splines, stratified by study arm, were used to test for potentially nonlinear or nonmonotone associations of pretreatment sCD30, SC163, or TARC with EFS. Two-sided P value <.10 was used as a significance threshold for tests of both nonlinearity and association with EFS to match the overall significance level specified in the study design of AHOD1331. Cox models and restricted cubic splines were also used to test for associations of pretherapy-to-posttherapy changes in sSC30, sCD163, and TARC with posttreatment EFS (defined from end of therapy), with each model adjusting for baseline values as potentially nonlinear effects while treating change from baseline as a linear effect. A set of unstratified Cox models containing interactions between study arm and marker effects (baseline and change from baseline models) were used to evaluate whether marker effects were modified by treatment. Statistical analyses were conducted using R.23

Results

T-cell responses targeting the tumor-associated antigen PRAME increased after therapy irrespective of treatment arm

Isolated and expanded T cells targeting 3 tumor-associated antigens were evaluated for functionality. Antigen-specific T-cell responses were evaluated in 72 patients (32 patients in each arm, for a total of 144 paired samples) with adequate samples expanded before and after therapy. Specificity (IFN-γ of >20 SFCs per 100 000 cells) was demonstrated to PRAME in 27 patients, to MAGE-A4 in 21 patients, and to survivin in 20 patients. For patients who received ABVE-PC, 8 had specificity to at least 1 antigen before treatment and 11 after treatment. Of patient samples analyzed that were randomized to Bv-AVEPC, 7 had specificity to at least 1 antigen before treatment and 15 after treatment. Mean specificity to PRAME at baseline was 12 IFN-γ SFCs per 100 000 cells (standard deviation [SD], 29), MAGE-A4 7 (SD, 15), and survivin 7 (SD, 17). After therapy, mean specificity to PRAME was 28 IFN-γ SFCs per 100 000 cells (SD, 54), MAGE-A4 28 (SD, 84), and survivin 10 (SD, 34). T cells specific for the TAA PRAME were significantly increased after therapy, with a mean increase of 12 IFN-γ SFCs per 100 000 cells as evaluated by enzyme-linked immunospot (P = .04; Figure 1). The mean difference after as compared with before therapy did not differ significantly across treatment groups.

Tumor-specific T cell response in response to tumor antigens MAGE-A4, PRAME and Survivin. T cell specificity to MAGE-A4 , PRAME, and Survivin both at baseline and post-therapy across both treatment arms (A) as measured by ELISpot in IFNγ SFC/100,000 cells (total n =144 and 72 per treatment arm) and (B) split by treatment arms (but due to numbers, without statistical relevance).

Tumor-specific T cell response in response to tumor antigens MAGE-A4, PRAME and Survivin. T cell specificity to MAGE-A4 , PRAME, and Survivin both at baseline and post-therapy across both treatment arms (A) as measured by ELISpot in IFNγ SFC/100,000 cells (total n =144 and 72 per treatment arm) and (B) split by treatment arms (but due to numbers, without statistical relevance).

Cytokine and chemokine profiling demonstrated an increase in proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines in patients after therapy across both treatment arms

A total of 592 peripheral blood samples were evaluated for cytokine and chemokine analysis: 184 paired pretherapy and posttherapy samples were analyzed with Luminex 17-plex multiplex cytokine assay;196 paired samples for sCD30 and sCD163; and 152 paired samples for TARC. Eighteen of these paired pretherapy and posttherapy samples were from patients who developed R/R disease, 6 had been randomized to receive BV-AVEPC and 12 to receive ABVE-PC. Patient, disease, and treatment characteristics did not differ significantly between trial participants with samples analyzed vs not analyzed (Table 1).

Proinflammatory cytokines, including those associated with T-cell activation, were evaluated before and after treatment to determine changes in immune milieu, which are beneficial to the tumor-specific T-cell immune response. Proinflammatory cytokines IFN-γ, IL-17a, and MCP1 significantly increased after therapy, whereas immunosuppressive IL-13 showed a significant decrease after therapy (Table 2). The mean increase in IFN-γ was 26.1 pg/mL (SD, 103.5; P = .0008), the mean increase in IL-17a was 12.9 pg/mL (SD, 78.1; P = .026), and the mean increase in MCP1 was 113.9 pg/mL (SD, 658.6; P = .02). IL-17a was the only cytokine that elicited a significant difference in patients who received Bv-containing treatment vs standard chemotherapy, with a smaller mean increase in the Bv arm (8.1 vs 17.6; Table 2). IL-13, considered an anti-inflammatory cytokine, had a pretreatment level mean of 2.70 pg/mL (SD, 5.71) vs 1.26 pg/mL (SD, 4.52) after treatment.

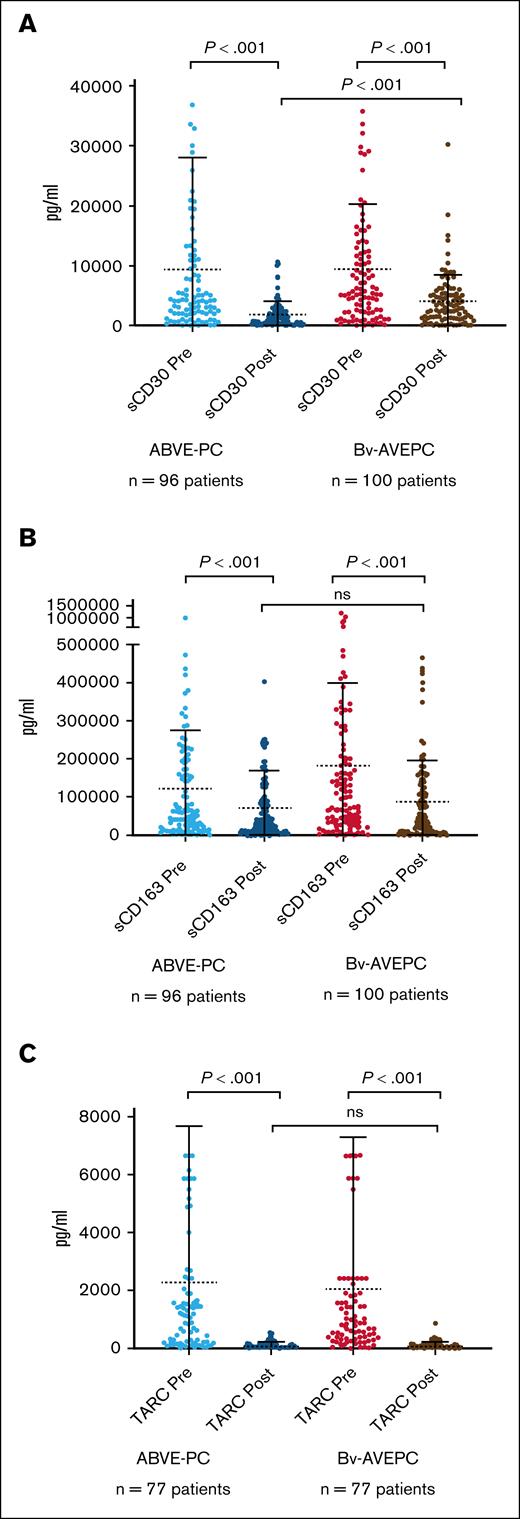

Peripheral blood sCD30, sCD163, and TARC levels significantly decreased in patients after treatment

Levels of CD30, sCD163, and TARC have been evaluated in patients with HL to determine whether baseline levels or changes in levels with treatment are predictive of response.13,14,18,24,25 In this study, sCD30, sCD163, and TARC significantly decreased after therapy (Figure 2), with P value <.0001 for each marker. Mean pretreatment TARC levels were 2165 pg/mL (SD, 5290) vs 96 pg/mL (SD, 122) after treatment; pretreatment sCD30 levels were 9352 pg/mL (SD, 1510) vs 2949 pg/mL (SD, 3681) after treatment; and pretreatment sCD163 levels were 151 819 pg/mL (SD, 189 467) falling to 79 076 pg/mL (SD, 101 696) after treatment (P < .0001). However, 75 of 152 (49%) baseline samples were greater than previously defined elevated TARC levels of 941 pg/mL.17 Pretreatment and posttreatment levels, and change in sCD30, sCD163, and TARC, did not vary by study arm except for posttreatment sCD30 being significantly higher among patients randomized to BV-AVEPC (P < .001; supplemental Table 1).

sCD30, sCD163, and TARC measured at baseline (before) and after therapy. sCD30 (A), sCD163 (B), and TARC (C) measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay at baseline and after therapy in both chemotherapy arm and chemotherapy with addition of Bv. ns, not significant.

sCD30, sCD163, and TARC measured at baseline (before) and after therapy. sCD30 (A), sCD163 (B), and TARC (C) measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay at baseline and after therapy in both chemotherapy arm and chemotherapy with addition of Bv. ns, not significant.

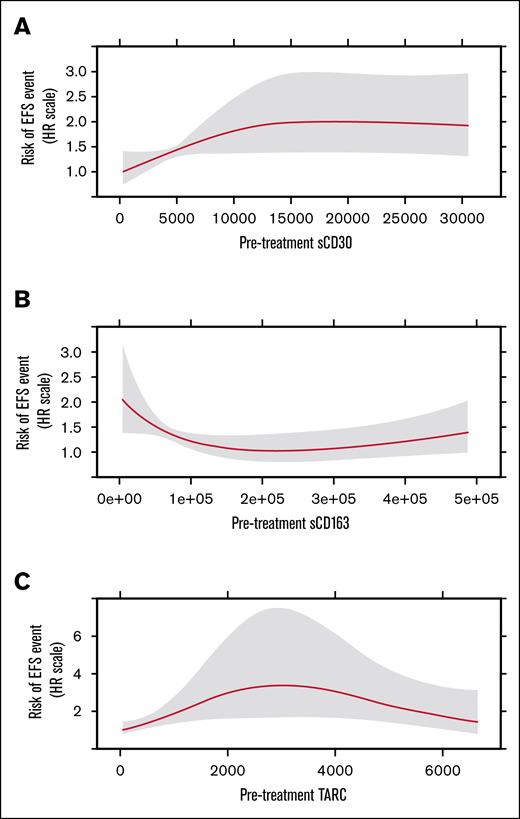

Association of pretreatment sCD30, sCD163, and TARC with EFS

sCD30

Figure 3A shows the risk of an EFS event on the relative hazard scale as a continuous function of pretreatment sCD30. The effect was nonlinear (P = .078), with the risk of an EFS event being lowest for patients with the lowest sCD30 values, increasing until sCD30 of ∼15 000 pg/mL, then remaining relatively flat for higher sCD30 values. The effect overall is statistically significant at the α level (α = 0.10) used in the study design of AHOD1331. However, this association of sCD30 with EFS did not reach statistical significance (P = .156).

Chemokine Pre-treatment values and EFS. Risk of EFS event as a function of pretreatment marker values for sCD30 (A), sCD163 (B), and TARC (C). HR, hazard ratio.

Chemokine Pre-treatment values and EFS. Risk of EFS event as a function of pretreatment marker values for sCD30 (A), sCD163 (B), and TARC (C). HR, hazard ratio.

sCD163

Figure 3B illustrates the relative risk of an EFS event as a function of sCD163, which was significantly nonlinear (P = .023). The greatest risk of an EFS event is for patients with the lowest sCD163 values; this risk decreases until sCD163 of ∼ 222 000 pg/mL; then increases for higher values of sCD163. The P value for the effect of sCD163 is .07, suggesting the effect overall is statistically significant at the α level (α = 0.10) used in the study design of AHOD1331.

TARC

Figure 3C illustrates the relative risk of an EFS event as a function of TARC, which was significantly nonlinear (P = .018). The lowest risk of an EFS event is for patients with the lowest TARC values; this risk increases until TARC of ∼3000 pg/mL; then decreases for higher values of TARC. The P value for the effect of TARC is .044, suggesting the effect overall is statistically significant at the α level (α = 0.10) used in the study design of AHOD1331.

Associations of pretreatment sCD30, sCD163, and TARC with EFS did not vary by treatment arm in interaction tests (P = .636, P = .20, and P = .62 respectively; supplemental Figure 1).

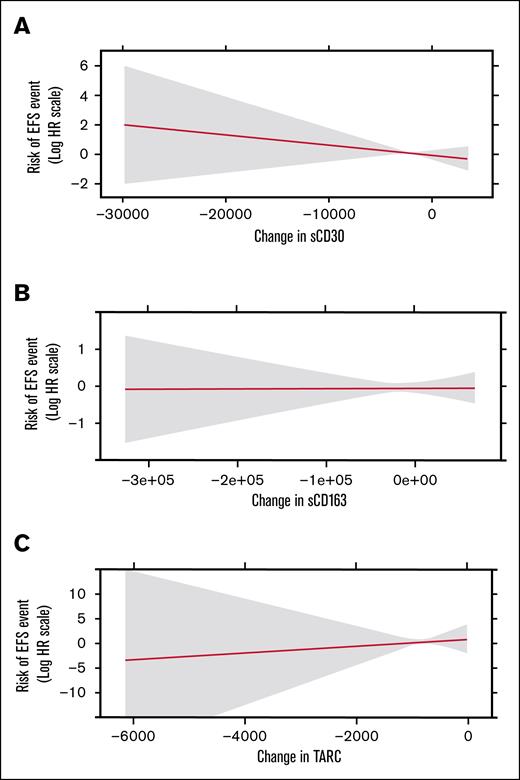

Association of pretreatment-to-posttreatment change in sCD30, sCD163, and TARC with posttreatment EFS

Figure 4 shows risk of a posttreatment EFS event on the relative hazard scale as a continuous function of changes in sCD30, sCD163, and TARC from before treatment to after treatment, respectively. Changes from baseline were not associated with subsequent EFS for any of the markers (P = .34, P = .96, and P = .70, respectively), and none of these effects differed significantly by study arm (P = .34, P = .41, and P = .20; supplemental Figure 2).

Change in chemokines and EFS. Risk of posttreatment EFS event as a function of marker change from before treatment to after treatment for sCD30 (A), sCD163 (B), and TARC (C). HR, hazard ratio.

Change in chemokines and EFS. Risk of posttreatment EFS event as a function of marker change from before treatment to after treatment for sCD30 (A), sCD163 (B), and TARC (C). HR, hazard ratio.

Discussion

The results of this correlative biology study demonstrate that both treatment regimens positively contributed to antitumor response: (1) T-cell responses to the TAA PRAME increased in patients after therapy in both treatment arms, and (2) proinflammatory as opposed to immunosuppressive cytokines also increased after treatment across both treatment arms. Levels of the 3 markers sCD30, TARC, and sCD163 all decreased significantly after treatment but were unaffected by treatment arm, and changes did not correlate with response. Although the risk of an EFS event is lowest for the lowest sCD30 levels, the effect overall is not statistically significant, possibly due to the low number of events reported in patients enrolled on AHOD1331.

Our results have implications for the identification of immune markers to guide future immunotherapies including cytotoxic T-cell therapies for the treatment of cHL by demonstrating evidence of proinflammatory cytokines in addition to increases in the tumor-specific T-cell immune responses. Pediatric patients with advanced-stage cHL had excellent outcomes on AHOD1331, with a 3-year EFS 92.1% in the Bv group as compared with 82.5% in the standard-care group.2 The relatively low numbers of events in the trial make statistically significant differences in chemokine and cytokine levels difficult, but our data support that immune biomarkers may be useful for identifying patients at higher risk for events especially because neither end-of-therapy nor interim positron emission tomography scans predicted poor survival for patients who received BV-AVPC on AHOD1331.

HL treatment on AHOD1331 resulted in increased T-cell responses to the TAA PRAME suggesting that immune recovery after treatment can promote TAA-specific T-cell immunity in vivo. In future studies, inclusion of T-cell receptor sequencing to identify expansion of novel tumor-specific clones would enrich understanding of tumor-specific responses. The tumor-directed T-cell response is dampened by HRS cells themselves in addition to the immune microenvironment they create. Recently, single-cell analysis of a small number of cases of cHL demonstrated some preserved TAA-directed effector functions of T cells within the tumor environment, raising interest in more functional studies of the T-cell antigen–directed response.26 Enhancing mechanisms of the native immune response with checkpoint inhibitors as well as the use of autologous adoptive cell therapy are additional therapeutic options for cHL, especially in an R/R setting.11,22 Cell therapies that have the potential to be explored in this setting include Epstein-Barr virus–directed T cells, non–gene-modified TAA T cells, and chimeric antigen receptor T cells10,11,27-29; and the decrease in immunosuppressive cytokines observed after therapy may indicate a more amenable immune environment for the administration of such therapies in the upfront setting.

A variety of chemokines associated with cHL have been evaluated as biomarkers for outcomes. Soluble TARC produced by HRS cells and detected in peripheral blood samples is significantly increased in most patients with cHL.12,14-17,25,30-32 TARC has been demonstrated to be higher in nonresponders than responders after therapy, although baseline TARC levels have not previously been shown to predict response.12-14,33 Our data, as compared with other reported data, did not have as consistently high baseline TARC levels, with only 50% of patients meeting the previously defined cutoff of 942 pg/mL, which maximized sum of sensitivity and specificity (with previously defined 97.9% sensitivity).17 Our data indicate that the lowest risk of an event is for patients with the lowest TARC values; however, the change in TARC did not correlate overall with EFS.

sCD30 and sCD163 have also been reported as potential biomarkers for disease response in cHL. In previous studies, sCD30 has been demonstrated to be high in most patients diagnosed with cHL, with a lower percentage having elevated sCD163.14,24 Although our data indicate that risk of an event is lowest at the lower levels of sCD30, this was not statistically significant. Currently, reported data have varying units of sCD30, making the standardization of such data collection difficult to compare across studies and standardization in future studies may aid in comparison. Patients who received Bv on AHOD1331 had superior EFS, indicating that additional mechanisms beyond targeting of CD30 contributed to improved outcomes. Interestingly, our data showed that the greatest risk of an EFS event is for patients with the lowest sCD163 values. Notably, these levels may not be reliable biomarkers when measured at only pretherapy and posttherapy time points. Although peripheral blood was collected to evaluate levels before treatment and after treatment on AHOD1331, a critical window of significant difference at an earlier collection time point such as at a time point after cycle 2 positron emission tomography may have been missed. Conflicting data have previously been reported regarding the significance of changes in levels from baseline to after therapy.13,14,25 sCD30, TARC, and sCD163 demonstrated significant decrease in all patients after therapy, but no statistically significant differences were seen in the Bv group vs the chemotherapy-alone group. The degree of change from baseline was also not associated with EFS.

This correlative biology study has certain limitations to address. The study was underpowered to detect differences in subgroups of patients. Because there were so few events, it was difficult to compare, in a statistically and clinically relevant way, the patients who experienced events vs those who did not, within each subgroup. Samples were batched to best compare baseline with posttherapy levels in paired samples. The definition of elevated levels of sCD30, sCD163, and TARC are not well defined so our aim was to compare levels within groups and changes across therapy, and standardization of testing of these markers may aid in future studies.

In summary, we prospectively collected peripheral blood samples of patients enrolled on AHOD1331 to evaluate tumor antigen-specific T-cell responses and gather information regarding the chemokine and cytokine profile with addition of Bv to standard chemotherapy. sCD30, sCD163, and TARC all decreased with treatment but did not differ significantly with the addition of Bv. Our data also conflicted with other reports regarding the significance of sCD30, TARC, and sCD163 as biomarkers for response, which may indicate that additional time points are needed for evaluation. Ultimately, these data support that treatment for HL using both the Bv-AVPC regimen, which was found to be superior for EFS as compared with chemotherapy alone, and chemotherapy without addition of Bv elicits a favorable environment for the incorporation of cellular or other immune-based therapies to prevent relapse in these patients, potentially obviating the need for adjunct radiotherapy.34 Although we did not detect significant differences across arms in regard to cytokine levels, future integrated correlative studies including cytokine and biomarker evaluation may more accurately differentiate the benefit of Bv in the immune microenvironment. As immunotherapy becomes incorporated into standard treatment schema for advanced-stage HL, additional studies will be required to evaluate the correlative biological effects on the immune environment as well as the potential opportunities for adjunct cell and other immune-based therapies to improve outcomes for pediatric patients with cHL.

Acknowledgments

Seagen Inc supplied brentuximab vedotin for the trial.

This study was supported, in part, by grants from the National Cancer Insitute (NCI), National Institutes of Health (NIH) to the Children’s Oncology Group (U10CA098543), National Clinical Trials Network (NCTN) Statistics and Data Center grant (U10CA180899), NCTN Operations Center grant (U10CA180886), COG Quality Assurance Review Center (QARC) (U10CA29511), Imaging and Radiation Oncology Core (IROC) Rhode Island (U24 CA180803), Children’s Oncology Group Hematopoietic Malignancies Integrated Translational Sciences Center, and the St. Baldrick’s Foundation. S.M.C. is funded, in part, by NIH grant R50CA 285492.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Authorship

Contribution: K.T., H.D., G.P., T.H., L.G.-R., K.M.K., F.G.K., S.M.C., and C.M.B. designed the study; G.P., K.T., and H.D. performed laboratory experiments and analysis; Q.P. and L.A.R. did the statistical analysis; K.T. wrote the first draft of the manuscript; and all authors commented on drafts of the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: L.G.-R. serves on an advisory board for Merck; and serves as an adviser to Roche. C.M.B. was a scientific cofounder of Mana Therapeutics and Catamaran Bio; is a current board member of Cabaletta Bio; holds stock in Neximmune and Repertoire Immune Medicines; serves on the Scientific Advisory Board of Minovia Therapeutics Ltd; and serves on the data and safety monitoring board for Sobi. S.M.C. serves on a pediatric advisory board for Seagen Inc (now Pfizer) and Bristol Meyers Squibb. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Keri Toner, Oncology, Children's National Hospital, 111 Michigan Ave NW, Washington, DC 20010; email: ktoner@childrensnational.org.

References

Author notes

Data are available on request from the corresponding author, Keri Toner (ktoner@childrensnational.org).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.