Key Points

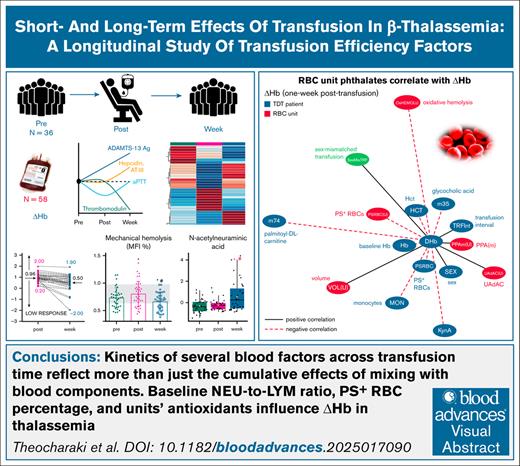

Blood kinetics across transfusion time in thalassemia reflect more than just the cumulative effects of mixing with blood components.

Baseline neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio index, phosphatidylserine exposure on patient and donor RBCs, and the antioxidant capacity of RBC units affect ΔHb in TDT.

Visual Abstract

The complex interplay between donor and recipient factors likely influences transfusion outcomes in transfusion-dependent thalassemia (TDT). We investigated physiological responses to transfusion shortly after it and 1 week later, focusing on hemoglobin (Hb) increment (ΔHb) and its determinants, using longitudinal data from 36 patients with TDT and 58 red blood cell (RBC) units. Immediate anemia correction after transfusion was associated with decreases in platelets and nucleated RBCs, increases in ADAMTS13 antigen and plasma amino acid levels, and temporary rises in hemolysis and phthalates. One week after transfusion, at the peak of erythroid suppression, plasma antioxidants and mechanical hemolysis decreased, whereas proteasome activity at the RBC membrane increased. Leukocyte levels declined, markers of thrombotic risk and endothelium dysfunction improved, and hepcidin as well as plasma glutamine and deoxyadenosine, increased. In addition to female sex and anemia, ΔHb was influenced by recipient baseline monocyte levels, hypercoagulability, and plasma metabolites, such as methionine, adenosine, acyl-carnitines, and bile acids. Donor RBC unit factors, including residual platelet levels, RBC proteasome activity, arginine metabolism, and catecholamine content also had significant correlations. Notably, the baseline neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio strongly affected ΔHb soon after transfusion, after adjusting for confounders. At the 1-week mark, ΔHb correlated with storability markers, such as oxidative hemolysis and phthalates, which, to our knowledge, is a first-ever described connection. Importantly, the percentage of phosphatidylserine-exposing donor RBCs and the uric acid–dependent antioxidant capacity of the RBC units significantly influenced ΔHb at the 1-week time point. These findings enhance our understanding of transfusion dynamics, paving the way for more personalized and effective care strategies in TDT management.

Introduction

Regular red blood cell (RBC) transfusions are essential for managing thalassemia major. However, repeated transfusions worsen iron overload, leading to serious complications.1 Differences in transfusion outcomes, such as hemoglobin (Hb) increment (ΔHb),2 stem from variations among donors/components, and recipients. For example, donor Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) status, recipient alloimmunization, and splenectomy affect RBC recovery in sickle cell disease (SCD),3 whereas blood processing methods influence mortality in acute-care recipients.4 Understanding these complex interactions is key to optimizing transfusion, making it an active area of research.5

Advanced donor-recipient data sets (eg, Scandinavian Donations and Transfusions [SCANDAT], The Recipient Epidemiology and Donor Evaluation Study-III [REDS-III], Transfusion Indication Threshold Reduction [TRUST]) facilitate the study of transfusion outcomes and hypothesis generation.6 Donor demographics, genetic variations (SEC14L4, HBA2, MYO9B, and G6PD),7 prolonged component storage, and recipient characteristics (eg, pretransfusion Hb) have been linked to ΔHb, 24 to 48 hours after transfusion.2 The RETRO (Red Cells in Outpatients Transfusion Outcomes) study of hematological malignancies identified transfusion dose, recipient age, blood volume, and pretransfusion Hb as key predictors of ΔHb shortly after transfusion.8 Smaller studies further linked transfused RBCs Hb content,9 storage duration,10 pretransfusion Hb,11,12 and recipient body surface area12 to ΔHb across various conditions. Although individual factors may have limited effects, their interactions, along with unidentified variables, are likely to determine transfusion efficacy.

Few studies have explored factors affecting transfusion outcomes in hemoglobinopathies and transfusion-dependent thalassemia (TDT). The National Institutes of Health–funded REDS-IV-P (Recipient Epidemiology and Donor Evaluation Study-IV-Pediatric) program aims to address this gap through the RBC-IMPACT (RBC-Improving Transfusions for Chronically Transfused Recipients), examining genetic and other determinants of transfusion efficacy in chronical transfusion recipients.13 In smaller-scale studies, the deformability and hemodynamic functionality of transfused RBCs were shown to influence ΔHb14,15 and posttransfusion blood flow16 in patients with TDT. A randomized crossover trial showed that transfusion of high Hb RBC units reduces annual transfusions in TDT.17 Additionally, in murine models, elevated reticulocyte (RET) counts in transfused blood (linked to donation frequency or iron supplementation) increase the immunogenicity and clearance of transfused RBCs.18 Finally, there is evidence that factors associated with patients with TDT have a greater impact on RBC recovery than donor characteristics.19

Additional considerations are essential for TDT. Use of leukoreduced, short-stored components entails trade-offs:20 lower storage lesions,21,22 but also lower RBC mass (potentially affecting ΔHb7), and unexpectedly heightened inflammatory responses.23 Moreover, patients with TDT differ markedly from other transfusion recipients (eg, trauma) in pathophysiology, anemia and erythropoiesis fluctuations, and higher pretransfusion Hb levels.2 Understanding of transfusion outcomes requires analyzing all aspects of participant involvement beyond demographics. Advances in omics technologies have provided deeper insights into storage lesions21 and thalassemia pathophysiology.24,25

This linked donor-recipient study investigates (1) transfusion-related changes in RBCs and plasma, including the metabolome; and (2) donor, component, and recipient variables linked to ΔHb and broader transfusion outcomes in a well-defined cohort of adult patients with TDT.25 The findings provide insights to support precision medicine strategies for enhancing transfusion efficacy in patients with TDT.

Patients and methods

Patients and RBC units

A total of 36 patients with TDT were examined longitudinally; before transfusion; 15 to 30 minutes after transfusion, to allow for fluid equilibrium26; and a week later, at the peak of erythroid suppression.27 A volume of RBCs left in the leukodepleted28 saline-adenine-glucose-mannitol RBC units after transfusion (N = 58) was also collected for analysis. Additional patient data and methodology are detailed in the supplemental Methods.

Laboratory analysis

Blood counts, serum/plasma biochemicals, and coagulation times (Table 2; supplemental Table 2) were measured.

Physiological measurements and metabolomics

Cell-free Hb was calculated by the method of Harboe.29 Total antioxidant capacity of plasma,30 was measured by the ferric reducing antioxidant power assay.31 Plasma procoagulant phospholipids were assessed by the STA-Procoag-PPL kit (Stago), which measures clotting time. Plasma extracellular vehicles (EV) were characterized in a NanoSight NS300 instrument (Malvern Panalytical, United Kingdom, established at the Hellenic Pasteur Institute).

Osmotic hemolysis,32 mechanical fragility index,33 and oxidative hemolysis (induced by 17 mM phenylhydrazine) were evaluated, as previously described. Intracellular reactive oxygen species accumulation was assessed by using the CM-H(2)DCFDA probe (Molecular Probes).34 Phosphatidylserine (PS) exposure on RBCs35 was estimated by flow cytometry (BD FACSCantoII). Membrane-bound hemichromes were assessed by the method of Ferru et al.36 Proteolytic proteasome activity (PPA)37 was estimated by using fluorogenic substrates and a pan-proteasome inhibitor (Enzo Life Sciences, NY). For metabolomics analysis, plasma samples were analyzed using a timsTOF Pro 2 coupled to an Elute ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography chromatographic system (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) with electrospray ionization source set in positive polarity.

Statistics and network analysis

Repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied for data kinetics. Between-group comparisons were conducted with independent t tests. Correlations were determined via bivariate analyses after assessing normality and outliers. Significant ΔHb correlations were visualized in networks (Cytoscape version 3.10.3). The metabolomics data set underwent ANOVA to detect significant differences across transfusion. Metabolites with an false discovery rate–adjusted P value <.05 were further analyzed post hoc. Multivariate analysis of covariance (ANOCOVA) was applied to significant parameters (extracted by univariate analyses) to evaluate influences on selected outcomes, accounting for potential confounders.38 Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were derived by logistic regression models fitted to ANOCOVA-derived variables. Data significance thresholds were set at P < .05. International Business Machines Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 25.0 (National and Kapodistrian University of Athens), GraphPad Prism 6, and MATLAB R2021a were used.

The study followed the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the institutional ethics committee of the collaborating hospitals (reference no. 4932/20-03-2020 and 65/08-11-2021).

Results

Patients with TDT and transfusion characteristics

Patients exhibited mild, moderate, or severe (β0/β+, β0/β0) deficiency in β-globin chains (Table 1). Transfusions were performed according to guidelines28 at ∼2-week intervals, with 1 or 2 units of prestorage-leukoreduced RBCs with mean age of <10 days. Typical25 for TDT blood counts (Table 2; supplemental Table 1), and serum biochemical profiles (Table 2; supplemental Table 2) were observed before transfusion (eg, disturbed iron homeostasis). Hepcidin concentration,25,27 and endothelial damage markers were normal, but prolonged coagulation times, and low protein C and factor XIII activities were measured. The blood donor cohort (Table 1) comprised mostly men, which led to a significant number (n = 26) of sex-mismatched transfusions.

Summary of patients with TDT and transfusion characteristics

| Patients with TDT | |

| Patients, N | 36 |

| Age, y | 48.75 (44.91-52.59) |

| Sex, male/female | 13/23 |

| Body mass index | 23.35 (22.51-24.18) |

| Smoking, n | 10 |

| ABO | 14A, 6B, 16O |

| Rhesus, +/− | 33/3 |

| β++/β++ or β++/β+ (mild deficiency), n | 10 |

| β+/β+ or β0/β++ (moderate deficiency), n | 18 |

| β0/β+ or β0/β0 (severe deficiency), n | 7∗ |

| Extramedullary hematopoiesis, yes/no | 11/25 |

| Splenectomy, yes/no | 22/14 |

| Cholecystectomy, yes/no | 17/19 |

| Hypogonadism, yes/no | 17/19 |

| Hypothyroidism, yes/no | 14/22 |

| Osteopenia, yes/no | 12/24 |

| Osteoporosis, yes/no | 17/19 |

| Pulmonary hypertension, yes/no | 7/29 |

| Atrial fibrillation, yes/no | 8/28 |

| Ferriprox, n | 11 |

| Exjade, n | 10 |

| Desferal, n | 3 |

| Ferriprox and Desferal, n | 9 |

| Ferriprox and Exjade, n | 2 |

| No chelation, n | 1 |

| Age of first transfusion, y | 16.06 (8.45-23.66) |

| Duration of transfusion therapy, y | 32.67 (26.42-38.91) |

| Interval since previous transfusion, d | 18.42 (16.03-20.80) |

| Average transfusion interval, d | 16.75 (15.63-17.87) |

| Units per transfusion, n | 1 unit, 13; 2 units, 23 |

| Donors and RBC units | |

| Donors/units, N | 58 |

| Age, y | 43.26 (40.80-45.72) |

| Sex, male/female | 45/13 |

| First-time donors, n | 10 |

| Storage age, d | 9.39 (7.42-11.36) |

| Total volume transfused,† mL | 537.5 (480.4-594.6) |

| RBC unit Hb, g | 92.73 (83.33-102.1) |

| Patients with TDT | |

| Patients, N | 36 |

| Age, y | 48.75 (44.91-52.59) |

| Sex, male/female | 13/23 |

| Body mass index | 23.35 (22.51-24.18) |

| Smoking, n | 10 |

| ABO | 14A, 6B, 16O |

| Rhesus, +/− | 33/3 |

| β++/β++ or β++/β+ (mild deficiency), n | 10 |

| β+/β+ or β0/β++ (moderate deficiency), n | 18 |

| β0/β+ or β0/β0 (severe deficiency), n | 7∗ |

| Extramedullary hematopoiesis, yes/no | 11/25 |

| Splenectomy, yes/no | 22/14 |

| Cholecystectomy, yes/no | 17/19 |

| Hypogonadism, yes/no | 17/19 |

| Hypothyroidism, yes/no | 14/22 |

| Osteopenia, yes/no | 12/24 |

| Osteoporosis, yes/no | 17/19 |

| Pulmonary hypertension, yes/no | 7/29 |

| Atrial fibrillation, yes/no | 8/28 |

| Ferriprox, n | 11 |

| Exjade, n | 10 |

| Desferal, n | 3 |

| Ferriprox and Desferal, n | 9 |

| Ferriprox and Exjade, n | 2 |

| No chelation, n | 1 |

| Age of first transfusion, y | 16.06 (8.45-23.66) |

| Duration of transfusion therapy, y | 32.67 (26.42-38.91) |

| Interval since previous transfusion, d | 18.42 (16.03-20.80) |

| Average transfusion interval, d | 16.75 (15.63-17.87) |

| Units per transfusion, n | 1 unit, 13; 2 units, 23 |

| Donors and RBC units | |

| Donors/units, N | 58 |

| Age, y | 43.26 (40.80-45.72) |

| Sex, male/female | 45/13 |

| First-time donors, n | 10 |

| Storage age, d | 9.39 (7.42-11.36) |

| Total volume transfused,† mL | 537.5 (480.4-594.6) |

| RBC unit Hb, g | 92.73 (83.33-102.1) |

Arithmetic mean (95% CI) (lower to upper 95% CI of mean).

CI, confidence interval.

In 1 patient, diagnosis was based on Hb analysis by high-performance liquid chromatography.

In 1-unit and 2-unit events.

Statistically significant changes in hematological and serum/plasma biochemicals in patients with TDT across transfusion

| Variable and control range . | Before . | After . | Week . | P value . | RBC units . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete blood count | |||||

| Hb (12.0-18.0 g/dL) | 9.7 ± 1.0 | 11.2 ± 1.0∗ | 10.6 ±0.9∗,† | .001 | 17.5 ± 1.7 |

| HCT (37%-52%) | 29.7 ± 3.1 | 34.0 ±3.0∗ | 32.3 ± 3.0∗,† | .001 | 57.3 ± 5.9 |

| RBC (4200 × 109/L to 6100 × 109/L) | 3700 ± 300 | 4200 ± 400∗ | 4000 ± 400∗,† | .001 | 6100 ± 800 |

| MCHC (33-37 g/dL) | 32.5 ± 1.3 | 33.0 ± 0.9∗ | 32.8 ± 1.1∗ | .001 | 30.6 ± 1.8 |

| RETs (50 ×109/L to 100 × 109/L) | 172.7 ± 256.1 | 187.6 ± 232.8∗ | 151.6 ± 201.7∗,† | <.001 | — |

| NRBCs, per 100 WBC | 76.0 ± 126.2 | 69.5 ± 116.1∗ | 35.2 ± 59.1∗,† | <.001 | — |

| WBC (5.2 × 109/L to 12.4 × 109/L) | 9.69 ± 4.20 | 9.76 ± 3.86 | 8.93 ± 4.02∗,† | .019 | 0.08 ± 0.11 |

| Lymphocytes, ×109/L | 2.56 ± 1.22 | 2.84 ± 1.32∗ | 2.67 ± 1.36 | .024 | 0.02 ± 0.04 |

| Monocytes (0.0 × 109/L to 0.8 × 109/L) | 0.74 ± 0.50 | 0.70 ± 0.45 | 0.59 ± 0.36∗,† | .003 | 0.01 ± 0.01 |

| EOSs (0.0 × 109/L to 0.5 × 109/L) | 0.18 ± 0.17 | 0.20 ± 0.17∗ | 0.16 ± 0.13† | .022 | — |

| Basophils (0.0 × 109/L to 0.2 × 109/L) | 0.12 ± 0.11 | 0.13 ± 0.10 | 0.11± 0.09† | .021 | — |

| PLTs (130 × 109/L to 400 × 109/L) | 422 ± 217 | 386 ± 195∗ | 391 ± 212∗ | <.001 | 3.5 ± 3.3 |

| RPR | 0.068 ± 0.066 | 0.070 ± 0.066∗ | 0.071 ± 0.065∗ | .010 | — |

| Serum/plasma biochemicals | |||||

| Hepcidin (0.079-49.4 ng/mL) | 29.2 ± 16.6 | 28.2 ± 16.4 | 29.8 ± 18.8∗ | .038 | — |

| Thrombomodulin (2866-5318 pg/mL) | 4771 ± 3730 | 4684 ± 3410 | 4409 ± 3663∗ | .031 | — |

| aPTT (27-35 s) | 35.9 ± 8.3 | 34.3 ± 8.2∗ | 35.9 ± 8.9 | .019 | — |

| Antithrombin III activity (75%-125% of control) | 90.2 ± 15.0 | 89.7 ± 15.5 | 91.4 ± 17.0∗,† | .049 | — |

| ADAMTS13:Ag (370-1403 ng/mL) | 1009 ± 354 | 1080 ± 354∗ | 1135 ± 481∗ | .034 | — |

| Variable and control range . | Before . | After . | Week . | P value . | RBC units . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete blood count | |||||

| Hb (12.0-18.0 g/dL) | 9.7 ± 1.0 | 11.2 ± 1.0∗ | 10.6 ±0.9∗,† | .001 | 17.5 ± 1.7 |

| HCT (37%-52%) | 29.7 ± 3.1 | 34.0 ±3.0∗ | 32.3 ± 3.0∗,† | .001 | 57.3 ± 5.9 |

| RBC (4200 × 109/L to 6100 × 109/L) | 3700 ± 300 | 4200 ± 400∗ | 4000 ± 400∗,† | .001 | 6100 ± 800 |

| MCHC (33-37 g/dL) | 32.5 ± 1.3 | 33.0 ± 0.9∗ | 32.8 ± 1.1∗ | .001 | 30.6 ± 1.8 |

| RETs (50 ×109/L to 100 × 109/L) | 172.7 ± 256.1 | 187.6 ± 232.8∗ | 151.6 ± 201.7∗,† | <.001 | — |

| NRBCs, per 100 WBC | 76.0 ± 126.2 | 69.5 ± 116.1∗ | 35.2 ± 59.1∗,† | <.001 | — |

| WBC (5.2 × 109/L to 12.4 × 109/L) | 9.69 ± 4.20 | 9.76 ± 3.86 | 8.93 ± 4.02∗,† | .019 | 0.08 ± 0.11 |

| Lymphocytes, ×109/L | 2.56 ± 1.22 | 2.84 ± 1.32∗ | 2.67 ± 1.36 | .024 | 0.02 ± 0.04 |

| Monocytes (0.0 × 109/L to 0.8 × 109/L) | 0.74 ± 0.50 | 0.70 ± 0.45 | 0.59 ± 0.36∗,† | .003 | 0.01 ± 0.01 |

| EOSs (0.0 × 109/L to 0.5 × 109/L) | 0.18 ± 0.17 | 0.20 ± 0.17∗ | 0.16 ± 0.13† | .022 | — |

| Basophils (0.0 × 109/L to 0.2 × 109/L) | 0.12 ± 0.11 | 0.13 ± 0.10 | 0.11± 0.09† | .021 | — |

| PLTs (130 × 109/L to 400 × 109/L) | 422 ± 217 | 386 ± 195∗ | 391 ± 212∗ | <.001 | 3.5 ± 3.3 |

| RPR | 0.068 ± 0.066 | 0.070 ± 0.066∗ | 0.071 ± 0.065∗ | .010 | — |

| Serum/plasma biochemicals | |||||

| Hepcidin (0.079-49.4 ng/mL) | 29.2 ± 16.6 | 28.2 ± 16.4 | 29.8 ± 18.8∗ | .038 | — |

| Thrombomodulin (2866-5318 pg/mL) | 4771 ± 3730 | 4684 ± 3410 | 4409 ± 3663∗ | .031 | — |

| aPTT (27-35 s) | 35.9 ± 8.3 | 34.3 ± 8.2∗ | 35.9 ± 8.9 | .019 | — |

| Antithrombin III activity (75%-125% of control) | 90.2 ± 15.0 | 89.7 ± 15.5 | 91.4 ± 17.0∗,† | .049 | — |

| ADAMTS13:Ag (370-1403 ng/mL) | 1009 ± 354 | 1080 ± 354∗ | 1135 ± 481∗ | .034 | — |

Repeated measures ANOVA or Friedman (Wilcoxon) tests. For hepcidin, n = 19; for aPTT, n = 22.

ADAMTS13:Ag, ADAMTS13 antigen; aPTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; EOSs, eosinophils; HCT, hematocrit; MCHC, mean corpuscular Hb concentration; PLTs, platelets; RDW, red cell distribution width; RPR, the ratio of (RDW × 100) to (platelets).

P < .05 vs before.

P < .05 vs after.

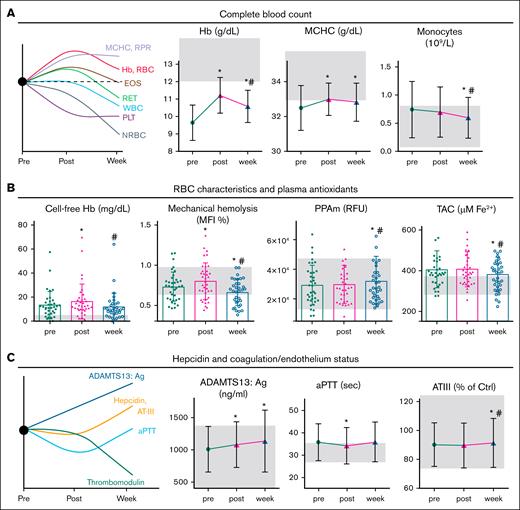

Posttransfusion changes in RBCs and plasma

Mean baseline and posttransfusion Hb levels were 9.7 ± 1.0 and 11.2 ± 1.0 g/dL, respectively (Table 2), as indicated.28 Hb concentration remained above baseline at the 1-week checkpoint (Figure 1A). Posttransfusion mean corpuscular Hb concentration, the ratio of red cell distribution width to platelets, and eosinophil count increased, in contrast to platelet and nucleated RBC (NRBC) counts. RET rose initially but dropped below baseline afterward, whereas the WBC and monocyte counts declined 1 week after transfusion (Figure 1A; Table 2). Other RBC indices showed no significant changes (supplemental Table 1).

Statistically significant changes in RBC and plasma features across transfusion time. (A) Complete blood count. (B) Fluctuations in RBC characteristics and plasma antioxidants. (C) Changes in hepcidin and coagulation/endothelium status markers. Repeated measures ANOVA with post hoc comparisons. ∗P < .05 vs before; #P < .05 vs after. Shaded area: control range in healthy participants (average ± standard deviation).25 aPTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; AT-III, antithrombin- III activity; Ctrl, control; EOS, eosinophil; MCHC, mean corpuscular Hb concentration; MFI, mechanical fragility index; PPAm, proteolytic proteasome activity at the RBC membrane; RPR, the ratio of red cell distribution width to platelets; TAC, total antioxidant capacity of plasma.

Statistically significant changes in RBC and plasma features across transfusion time. (A) Complete blood count. (B) Fluctuations in RBC characteristics and plasma antioxidants. (C) Changes in hepcidin and coagulation/endothelium status markers. Repeated measures ANOVA with post hoc comparisons. ∗P < .05 vs before; #P < .05 vs after. Shaded area: control range in healthy participants (average ± standard deviation).25 aPTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; AT-III, antithrombin- III activity; Ctrl, control; EOS, eosinophil; MCHC, mean corpuscular Hb concentration; MFI, mechanical fragility index; PPAm, proteolytic proteasome activity at the RBC membrane; RPR, the ratio of red cell distribution width to platelets; TAC, total antioxidant capacity of plasma.

Regarding RBC physiology, cell-free Hb exhibited a temporary increase after transfusion (Figure 1B). The rise was equal in 1- and 2-unit transfusions; however, it was positively correlated with storage hemolysis in 2-unit (r = .520, P = .011) but not in 1-unit events. Oxidative and osmotic hemolysis remained stable (Table 3), but mechanical hemolysis briefly rose before dropping (below baseline) at the 1-week time point (Figure 1B). PS exposure, oxidative stress markers, and cytosolic PPA remained largely unchanged after transfusion (Table 3), in contrast to the chymotrypsin- and caspase-like activities that showed a delayed increase at RBC membranes (Table 3; Figure 1B). Plasma antioxidants also exhibited a delayed decrease (Figure 1B), likely attributed to reduced uric acid (UA) activity (Table 3).

RBC and plasma physiological metrics in patients with TDT across transfusion

| Variable . | Before . | After . | Week . | P value . | RBC units . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemolysis rate | ||||||

| Cell-free Hb, mg/dL | 13.3 ± 11.4 | 16.4 ±14.5∗ | 11.7 ± 11.7† | .008 | 72.6 ± 65.4∗ | <.001 |

| Osmotic hemolysis, MCF, NaCl% | 0.378 ± 0.048 | 0.385 ± 0.043 | 0.385 ± 0.042 | .077 | 0.458 ± 0.025∗ | <.001 |

| Osmotic hemolysis, 24 hours, MCF, NaCl% | 0.419 ± 0.065 | 0.429 ± 0.057‡ | 0.434 ± 0.056‡ | .061 | 0.493 ± 0.035∗ | <.001 |

| Mechanical hemolysis, MFI, % | 0.732 ± 0.182 | 0.802 ± 0.227∗ | 0.663 ± 0.161∗,† | <.001 | 0.978 ± 0.273∗ | <.001 |

| Oxidative hemolysis, mg/dL | 7.4 ± 7.6 | 6.4 ± 6.0 | 8.4 ± 7.2 | ns | 11.2 ± 9.7∗ | .010 |

| Oxidative stress | ||||||

| ROS, RFU | 652 ± 415 | 524 ± 186 | 686 ± 293† | .023 | 546 ± 233 | ns |

| tBHP-induced ROS, RFU | 3242 ± 1606 | 3085 ± 2339 | 4471 ± 3927 | ns | 2909 ± 2345‡ | .082 |

| PHZ-induced ROS, RFU | 7633 ± 1324 | 8149 ± 1699 | 8215 ± 2621 | ns | 8527 ± 1623∗ | .013 |

| Membrane-bound hemichromes, μΜ | 25.9 ± 6.4 | 26.8 ± 6.7 | 30.2 ± 7.7‡ | .061 | 22.6 ± 5.3‡ | .074 |

| PS+ RBCs, % | 0.86 ± 1.12 | 0.79 ± 1.00 | 0.69 ± 0.93 | ns | 0.23 ± 0.15∗ | <.001 |

| Proteolytic proteasome activity | ||||||

| CH-like, RFU | 29 161 ± 13 451 | 29 690 ± 12915 | 31 618 ± 17 068 | ns | 28 526 ± 13 289 | ns |

| CASP-like, RFU | 19 162 ± 8051 | 18 874 ± 4868 | 19 272 ± 6850 | ns | 19 172 ± 5 936 | ns |

| TR-like, RFU | 48 420 ± 17 168 | 52 596 ± 18410 | 53 394 ± 18 781 | ns | 44 305 ± 12 097 | ns |

| CH-like, m, RFU | 26 209 ± 22 747 | 25 423 ± 15 046 | 36 494 ± 25 101∗,† | .003 | 44 142 ± 30 656∗ | .004 |

| CASP-like, m, RFU | 21 222 ± 19 234 | 22 757 ± 18 233 | 29 478 ± 19 267∗,† | .007 | 35 463 ± 27 523∗ | .011 |

| TR-like, m, RFU | 27 755 ± 28 048 | 26 053 ± 21 901 | 31 217 ± 25 752 | ns | 29 430 ± 20 838 | ns |

| Plasma sEVs | ||||||

| sEV concentration, ×1010/mL | 20.2 ± 8.4 | 20.4 ± 9.5 | 21.2 ± 9.6 | ns | 7.4 ± 3.3∗ | .004 |

| sEV size, nm | 159 ± 24 | 152 ± 25 | 151 ± 28 | .093 | 110 ± 14∗ | <.001 |

| Plasma antioxidant capacity | ||||||

| TAC, μM Fe2+ | 406 ± 91 | 407 ± 87 | 381 ± 86∗,† | .024 | 248 ± 54∗ | <.001 |

| UAiAC, μM Fe2+ | 217 ± 73 | 210 ± 72 | 207 ± 66 | ns | 124 ± 47∗ | <.001 |

| UAdAC, μM Fe2+ | 190 ± 60 | 197 ± 54 | 174 ± 67† | .018 | 124 ± 32∗ | <.001 |

| Variable . | Before . | After . | Week . | P value . | RBC units . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemolysis rate | ||||||

| Cell-free Hb, mg/dL | 13.3 ± 11.4 | 16.4 ±14.5∗ | 11.7 ± 11.7† | .008 | 72.6 ± 65.4∗ | <.001 |

| Osmotic hemolysis, MCF, NaCl% | 0.378 ± 0.048 | 0.385 ± 0.043 | 0.385 ± 0.042 | .077 | 0.458 ± 0.025∗ | <.001 |

| Osmotic hemolysis, 24 hours, MCF, NaCl% | 0.419 ± 0.065 | 0.429 ± 0.057‡ | 0.434 ± 0.056‡ | .061 | 0.493 ± 0.035∗ | <.001 |

| Mechanical hemolysis, MFI, % | 0.732 ± 0.182 | 0.802 ± 0.227∗ | 0.663 ± 0.161∗,† | <.001 | 0.978 ± 0.273∗ | <.001 |

| Oxidative hemolysis, mg/dL | 7.4 ± 7.6 | 6.4 ± 6.0 | 8.4 ± 7.2 | ns | 11.2 ± 9.7∗ | .010 |

| Oxidative stress | ||||||

| ROS, RFU | 652 ± 415 | 524 ± 186 | 686 ± 293† | .023 | 546 ± 233 | ns |

| tBHP-induced ROS, RFU | 3242 ± 1606 | 3085 ± 2339 | 4471 ± 3927 | ns | 2909 ± 2345‡ | .082 |

| PHZ-induced ROS, RFU | 7633 ± 1324 | 8149 ± 1699 | 8215 ± 2621 | ns | 8527 ± 1623∗ | .013 |

| Membrane-bound hemichromes, μΜ | 25.9 ± 6.4 | 26.8 ± 6.7 | 30.2 ± 7.7‡ | .061 | 22.6 ± 5.3‡ | .074 |

| PS+ RBCs, % | 0.86 ± 1.12 | 0.79 ± 1.00 | 0.69 ± 0.93 | ns | 0.23 ± 0.15∗ | <.001 |

| Proteolytic proteasome activity | ||||||

| CH-like, RFU | 29 161 ± 13 451 | 29 690 ± 12915 | 31 618 ± 17 068 | ns | 28 526 ± 13 289 | ns |

| CASP-like, RFU | 19 162 ± 8051 | 18 874 ± 4868 | 19 272 ± 6850 | ns | 19 172 ± 5 936 | ns |

| TR-like, RFU | 48 420 ± 17 168 | 52 596 ± 18410 | 53 394 ± 18 781 | ns | 44 305 ± 12 097 | ns |

| CH-like, m, RFU | 26 209 ± 22 747 | 25 423 ± 15 046 | 36 494 ± 25 101∗,† | .003 | 44 142 ± 30 656∗ | .004 |

| CASP-like, m, RFU | 21 222 ± 19 234 | 22 757 ± 18 233 | 29 478 ± 19 267∗,† | .007 | 35 463 ± 27 523∗ | .011 |

| TR-like, m, RFU | 27 755 ± 28 048 | 26 053 ± 21 901 | 31 217 ± 25 752 | ns | 29 430 ± 20 838 | ns |

| Plasma sEVs | ||||||

| sEV concentration, ×1010/mL | 20.2 ± 8.4 | 20.4 ± 9.5 | 21.2 ± 9.6 | ns | 7.4 ± 3.3∗ | .004 |

| sEV size, nm | 159 ± 24 | 152 ± 25 | 151 ± 28 | .093 | 110 ± 14∗ | <.001 |

| Plasma antioxidant capacity | ||||||

| TAC, μM Fe2+ | 406 ± 91 | 407 ± 87 | 381 ± 86∗,† | .024 | 248 ± 54∗ | <.001 |

| UAiAC, μM Fe2+ | 217 ± 73 | 210 ± 72 | 207 ± 66 | ns | 124 ± 47∗ | <.001 |

| UAdAC, μM Fe2+ | 190 ± 60 | 197 ± 54 | 174 ± 67† | .018 | 124 ± 32∗ | <.001 |

Before, after, week: repeated measures ANOVA or Friedman (Wilcoxon) tests; RBC units vs before: independent t test or Mann-Whitney U (2 samples) test.

CASP, caspase; CH, chymotrypsin; m; membrane; MCF, mean corpuscular fragility index; MFI, mechanical fragility index; ns, not significant; PHZ, phenylhydrazine; RFU, relative fluorescence units; ROS, reactive oxygen species; sEV, small EVs; TAC, total antioxidant capacity; tBHP, tert-butyl hydroperoxide; TR, trypsin; UAiAC, UA-independent antioxidant capacity; UAdAC, UA-dependent antioxidant capacity.

P < .05 vs before.

P < .05 vs after.

.05 < P < .10 (statistical trend).

At the 1-week time point, hepcidin levels increased as opposed to thrombomodulin (Figure 1C; Table 2). Coagulation factors, modulators, and clotting times remained largely unchanged (supplemental Table 2), except for (1) activated partial thromboplastin time, which temporarily decreased; (2) ADAMTS13 antigen, which steadily increased; and (3) antithrombin-III activity, which showed a delayed increase after transfusion. The concentration/size of small EV remained relatively stable (Table 3), with a significant variability, however, among patients (supplemental Figure 1A-B), revealing differential transfusion effects. Two-unit transfusions had higher plasma EV levels and increment soon after transfusion over 1-unit events (supplemental Figure 1C), suggesting triggered EV generation in patients. The RBC units exhibited lesions consistent39,40 with their short storage duration, including low hemolysis (0.13% ± 0.11% or 72.6 ± 65.4 mg/dL; Table 3). Despite that, oxidative hemolysis and other measures differed substantially compared with the TDT baseline physiological status (Table 3).

To assess the effects of patient and component factors on posttransfusion kinetics, we conducted a multivariate ANOCOVA (supplemental Figure 2). Key findings included:

Splenectomy positively influenced activated partial thromboplastin time (F = 11.12); ADAMTS13 antigen (1 week); and notably, RBC membrane PPA levels after transfusion.

The severity of mutations affected the platelet (shortly after) and NRBC counts (1 week) after transfusion.

Storage age and hemolysis had minimal impact; however, Hb concentration of RBC units influenced the kinetics of patient WBC levels 1 week after transfusion (P = .017).

Transfusion dose (units per event) positively affected hepcidin and membrane PPA kinetics (F = 13.1). There was a trend toward lower membrane PPA in patients receiving 1 vs 2 units (16349 ± 4391 vs 20670 ± 7437 relative fluorescence units [RFU], respectively).

Plasma metabolome also varied after transfusion. Figure 2A highlights the top 60 differentially expressed metabolites across time points. Norepinephrine (octopamine) levels declined, whereas citrulline, carnitine, hydrocortisone, arginine, and other amino acids increased. Hypoxanthine showed a late increase, whereas phthalic acid and other di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) metabolites, such as mono-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (MEHP) and mono-(7-carboxy-n-heptyl)phthalate (MCHP), displayed temporary increases, as previously reported.41 ANOVA with post hoc testing identified 18 metabolites significantly altered over time (Figure 2B). 2-Amino-isobutyric acid; phthalic acid (Figure 2C); MEHP; MCHP; and, of note, monoisononyl phthalate fluctuated reversibly, whereas certain amino acids and monomethyl phthalate (MMP) exhibited early and sustained increases after transfusion (Figure 2D). l-Glutamine, deoxyadenosine, modified amino acids, N-acetylneuraminic acid, and γ-aminobutyric acid showed significant increases later after transfusion (Figure 2E). One-unit transfusions were associated with higher L-arginine levels (P < .05) and a trend toward lower DEHP metabolites (eg, MEHP, P = .065) in the recipient, than 2-unit transfusions.

Variation in plasma metabolites across transfusion time. (A) Heat map showing the mean differential expression of the top 60 metabolites identified by targeted metabolomics across time points. (B) Summary of TDT metabolites that changed significantly (fold change vs before; P < .05) in the posttransfusion period (Post, Week), based on ANOVA with post hoc tests. Fold change levels (vs before [Pre]) in RBC unit supernatants are also presented. Red tones, increase; blue tone, decrease. The metabolites are classified in 3 groups based on their response to transfusion: those showing reversible early response, irreversible early response, or late response. Representative examples are shown in the box plots (C-E), denoting the normalized (cube root transformation) and scaled (autoscaling) peak areas of metabolites with pronounced differences between the 3 timepoints. The bars of the box plots depict the median along with the interquartile range. ∗P < .05 vs before; #P < .05 vs after. 2-ABA, 2-amino-isobutyrate; GABA, γ-aminobutyrate; MCiOP, mono-(carboxy-iso-octyl) phthalate; MiNP, monoisononyl phthalate.

Variation in plasma metabolites across transfusion time. (A) Heat map showing the mean differential expression of the top 60 metabolites identified by targeted metabolomics across time points. (B) Summary of TDT metabolites that changed significantly (fold change vs before; P < .05) in the posttransfusion period (Post, Week), based on ANOVA with post hoc tests. Fold change levels (vs before [Pre]) in RBC unit supernatants are also presented. Red tones, increase; blue tone, decrease. The metabolites are classified in 3 groups based on their response to transfusion: those showing reversible early response, irreversible early response, or late response. Representative examples are shown in the box plots (C-E), denoting the normalized (cube root transformation) and scaled (autoscaling) peak areas of metabolites with pronounced differences between the 3 timepoints. The bars of the box plots depict the median along with the interquartile range. ∗P < .05 vs before; #P < .05 vs after. 2-ABA, 2-amino-isobutyrate; GABA, γ-aminobutyrate; MCiOP, mono-(carboxy-iso-octyl) phthalate; MiNP, monoisononyl phthalate.

Finally, the RBC units were enriched with metabolites from the acidic storage medium, carboxylic acids, storage lesion markers (eg, DEHP compounds), non-DEHP phthalates (such as MMP), and melatonin (detected in 60% of the units) compared with the TDT plasma before transfusion (supplemental Figure 3). The antioxidants L-carnosine and ascorbate were significantly lower. DEHP-derived metabolites (phthalic acid and MEHP) positively correlated with storage duration (r = .615, P < .0001), whereas MCHP negatively (r = −0.3746, P = .0038), indicating faster degradation during storage (supplemental Figure 4A). In contrast, the non-DEHP phthalates (MMP, monoisononyl phthalate, and mono-(carboxy-iso-octyl) phthalate) showed no correlation with storage age (supplemental Figure 4B).

ΔHb varies widely among patients at both time points after transfusion

ΔHb (normalized per RBC unit) showed significant variability among patients shortly after transfusion (ΔHbpost: 0.96 ± 0.38 g/dL; range 0.20-2.00) and 1 week later (ΔHbweek: 0.50 ± 0.70 g/dL; range, −2.00 to 1.90; Figure 3A). To identify potential contributing factors, we compared subgroups of low vs high ΔHb (threshold set at cohort median) for differences in donor/component and recipient characteristics.

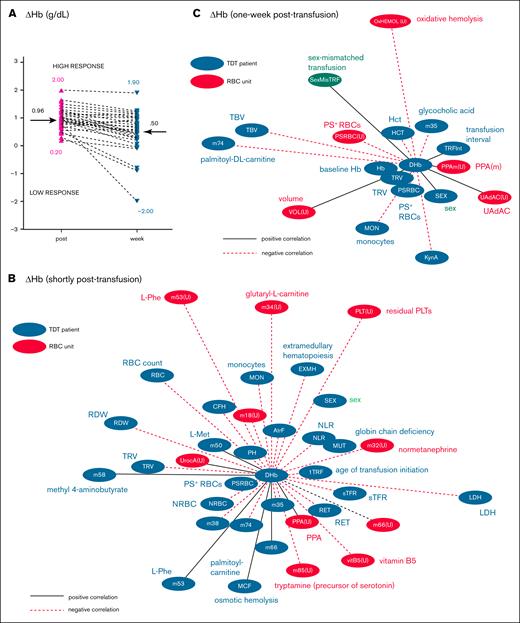

ΔHb variation and linkages with data of donors and patients with TDT. (A) ΔHb variation (normalized values per RBC unit) among patients with TDT shortly (post) and 1-week (week) after transfusion. The cohort medians (grams per deciliter) that distinguish low from high transfusion response events are denoted by arrows. (B-C) Network presentation of RBC unit variables, donor variables, and baseline variables of patients with TDT significantly correlated (P < .05) with ΔHbpost (B) and ΔHbweek (C) according to the univariate analyses shown in supplemental Table 4 and supplemental Table 6, respectively. Edge length is inversely proportional to the correlation coefficient (r), with shorter edges indicating stronger correlations. Black/solid lines, positive correlations; red/dashed lines, negative correlations. Metabolite (m) numbers in nodes correspond to definitions in supplemental Tables 4 and 6. AtrF, atrial fibrillation; CFH, cell-free Hb; DHb, ΔHb; EXMH, extramedullary hematopoiesis; HCT, hematocrit; Hct, hematocrit; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; m, membrane; MCF, mean corpuscular fragility; MON, monocyte; MUT, mutation severity; PH, pulmonary hypertension; Phe, phenylalanine; PPA, proteolytic proteasome activity; PPA(U), PPA of RBC units; PPAm(U), proteolytic proteasome activity at the RBC membrane (units); PSRBC(U), PS-exposing RBCs (units); RDW, red cell distribution width; RET, reticulocytes; sTFR, soluble transferrin receptor; TBV, total blood volume; 1TRF, age of transfusion initiation; TRFInt, transfusion interval; TRV, total RBC volume; UAdAC, UA-dependent antioxidant capacity; UAdAC(U), UAdAC of RBC units; UrocA(U), Urocanic acid (units) ; VOL(U), volume of RBC units.

ΔHb variation and linkages with data of donors and patients with TDT. (A) ΔHb variation (normalized values per RBC unit) among patients with TDT shortly (post) and 1-week (week) after transfusion. The cohort medians (grams per deciliter) that distinguish low from high transfusion response events are denoted by arrows. (B-C) Network presentation of RBC unit variables, donor variables, and baseline variables of patients with TDT significantly correlated (P < .05) with ΔHbpost (B) and ΔHbweek (C) according to the univariate analyses shown in supplemental Table 4 and supplemental Table 6, respectively. Edge length is inversely proportional to the correlation coefficient (r), with shorter edges indicating stronger correlations. Black/solid lines, positive correlations; red/dashed lines, negative correlations. Metabolite (m) numbers in nodes correspond to definitions in supplemental Tables 4 and 6. AtrF, atrial fibrillation; CFH, cell-free Hb; DHb, ΔHb; EXMH, extramedullary hematopoiesis; HCT, hematocrit; Hct, hematocrit; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; m, membrane; MCF, mean corpuscular fragility; MON, monocyte; MUT, mutation severity; PH, pulmonary hypertension; Phe, phenylalanine; PPA, proteolytic proteasome activity; PPA(U), PPA of RBC units; PPAm(U), proteolytic proteasome activity at the RBC membrane (units); PSRBC(U), PS-exposing RBCs (units); RDW, red cell distribution width; RET, reticulocytes; sTFR, soluble transferrin receptor; TBV, total blood volume; 1TRF, age of transfusion initiation; TRFInt, transfusion interval; TRV, total RBC volume; UAdAC, UA-dependent antioxidant capacity; UAdAC(U), UAdAC of RBC units; UrocA(U), Urocanic acid (units) ; VOL(U), volume of RBC units.

Table 4 outlines significant baseline differences between high/low ΔHb groups. Recipients with high ΔHbpost exhibited low baseline neutrophil and monocyte counts, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and PS+ RBCs, along with smaller plasma EV. Thrombotic risk markers were more favorable (lower von Willebrand factor antigen and higher free protein S). Plasma metabolome differences included upregulation of methionine, and downregulation of adenosine and glycocholate. Posttransfusion differences in NLR and free protein S are shown in supplemental Table 3. RBC units delivered to the high-ΔHbpost group had fewer residual platelets, and lower procoagulant phospholipid activity, 2-amino-isobutyric acid, acylcarnitines, and normetanephrine levels in the supernatant, with trends toward reduced norepinephrine (P = .069), dopamine (P = .084), and dimethyl-arginine (P = .079). Transfusion dose did not affect normalized ΔHbpost.

Baseline (before transfusion) differences between patients with low and high ΔHb, as well as among RBC units used in their transfusion events

| ΔHbpost-related variable . | Low . | High . | P value . | ΔHbweek-related variable . | Low . | High . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Patients with TDT, baseline | |||||||

| Complete blood count and biochemicals | Complete blood count and biochemicals | ||||||

| NEU, ×109/L | 6.40 ± 3.38 | 3.97 ± 1.87 | .033 | Hb, g/dL | 10.12 ± 0.84 | 9.19 ± 0.97 | .007 |

| MON, 109/L | 0.94 ± 0.57 | 0.54 ± 0.32 | .024 | HCT, % | 31.07 ± 2.65 | 28.34 ± 2.98 | .007 |

| NLR | 3.00 ± 1.63 | 1.57 ± 0.61 | .007 | PT/INR | 1.41 ± 0.58 | 1.16 ± 0.09 | .036 |

| Free protein S (% of control) | 49.1 ± 17.9 | 61.7 ± 12.5 | .029 | α2-Macroglobulin, mg/dL | 161 ± 94 | 229 ± 77 | .026 |

| VWF antigen (% of control) | 102.9 ± 44.6 | 81.9 ± 22.3 | .091 | — | — | — | — |

| RBCs and EVs | RBCs | ||||||

| PS+ RBCs, % | 1.26 ± 1.39 | 0.39 ± 0.33 | .001 | PS+ RBCs, % | 1.17 ± 1.44 | 0.52 ± 0.50 | .045 |

| EVs size, nm | 202 ± 73 | 158 ± 42 | .080 | — | — | — | — |

| Plasma metabolites | Plasma metabolites | ||||||

| Adenosine | 0.511 ± 1.241 | 0.325 ± 0.113 | .041 | 5-Oxoproline | 3.001 ± 0.606 | 3.365 ± 0.447 | .045 |

| Glycocholic acid | 2.594 ± 3.363 | 0.576 ± 0.480 | .018 | N-methyl-l-glutamic acid | 0.100 ± 0.028 | 0.079 ± 0.028 | .035 |

| L-methionine | 0.096 ±0.080 | 0.174 ±0.106 | .021 | MiNP | 0.014 ± 0.023 | 0.006 ± 0.012 | .029 |

| B. RBC units | |||||||

| Complete blood count | Complete blood count | ||||||

| PLT, 109/L | 3.68 ±2.45 | 2.2 ± 1.7 | .038 | — | — | — | — |

| RBCs and EVs | RBCs and EVs | ||||||

| PS+RBC, % | 0.25 ± 0.14 | 0.19 ± 0.16 | .066 | Oxidative hemolysis, mg/dL | 14.9 ± 11.7 | 7.5 ± 5.3 | .031 |

| TR-like PPA, RFU | 40655 ± 10182 | 48410 ± 13056 | .061 | Osmotic hemolysis, 24 hours, MCF, NaCl% | 0.506 ± 0.033 | 0.481 ± 0.034 | .051 |

| Procoagulant phospholipid activity, % | 13. 0 ± 7.0 | 7.3 ± 3.8 | .032 | CH-like PPA, m, RFU | 31349 ± 15009 | 59887 ± 37743 | .032 |

| Supernatant metabolites | Supernatant metabolites | ||||||

| Dimethyl-arginine | 4.67 ± 1.10 | 4.29 ± 1.65 | .079 | L-Arginine | 0.067± 0.108 | 0.117 ± 0.201 | .065 |

| Dopamine | 4.75 ± 2.10 | 3.81 ± 1.53 | .084 | L-Homocysteine | 0.001 ± 0.003 | 0.004 ± 0.006 | .045 |

| Norepinephrine | 1.49 ± 0.62 | 1.19 ± 0.49 | .022 | Melatonin | 1.41 ± 1.15 | 0.63 ± 0.83 | .018 |

| Normetanephrine | 31.82 ± 6.74 | 27.56 ± 7.77 | .009 | Thiamine monophosphate | 0.084 ± 0.088 | 0.139 ± 0.087 | .020 |

| Glutaryl-L-carnitine | 4.46 ± 3.14 | 2.80 ± 2.59 | .069 | Phthalic acid | 43.01 ± 28.92 | 29.58 ± 25.39 | .017 |

| 2-Amino-isobutyric acid | 0.127 ± 0.042 | 0.102 ± 0.042 | .038 | MEHP | 14.20 ± 8.76 | 10.13 ± 7.75 | .020 |

| — | — | — | — | MMP | 0.290 ± 0.474 | 0.140 ± 0.248 | .037 |

| — | — | — | — | d-Lactose | 0.298 ± 0.122 | 0.259 ± 0.204 | .037 |

| ΔHbpost-related variable . | Low . | High . | P value . | ΔHbweek-related variable . | Low . | High . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Patients with TDT, baseline | |||||||

| Complete blood count and biochemicals | Complete blood count and biochemicals | ||||||

| NEU, ×109/L | 6.40 ± 3.38 | 3.97 ± 1.87 | .033 | Hb, g/dL | 10.12 ± 0.84 | 9.19 ± 0.97 | .007 |

| MON, 109/L | 0.94 ± 0.57 | 0.54 ± 0.32 | .024 | HCT, % | 31.07 ± 2.65 | 28.34 ± 2.98 | .007 |

| NLR | 3.00 ± 1.63 | 1.57 ± 0.61 | .007 | PT/INR | 1.41 ± 0.58 | 1.16 ± 0.09 | .036 |

| Free protein S (% of control) | 49.1 ± 17.9 | 61.7 ± 12.5 | .029 | α2-Macroglobulin, mg/dL | 161 ± 94 | 229 ± 77 | .026 |

| VWF antigen (% of control) | 102.9 ± 44.6 | 81.9 ± 22.3 | .091 | — | — | — | — |

| RBCs and EVs | RBCs | ||||||

| PS+ RBCs, % | 1.26 ± 1.39 | 0.39 ± 0.33 | .001 | PS+ RBCs, % | 1.17 ± 1.44 | 0.52 ± 0.50 | .045 |

| EVs size, nm | 202 ± 73 | 158 ± 42 | .080 | — | — | — | — |

| Plasma metabolites | Plasma metabolites | ||||||

| Adenosine | 0.511 ± 1.241 | 0.325 ± 0.113 | .041 | 5-Oxoproline | 3.001 ± 0.606 | 3.365 ± 0.447 | .045 |

| Glycocholic acid | 2.594 ± 3.363 | 0.576 ± 0.480 | .018 | N-methyl-l-glutamic acid | 0.100 ± 0.028 | 0.079 ± 0.028 | .035 |

| L-methionine | 0.096 ±0.080 | 0.174 ±0.106 | .021 | MiNP | 0.014 ± 0.023 | 0.006 ± 0.012 | .029 |

| B. RBC units | |||||||

| Complete blood count | Complete blood count | ||||||

| PLT, 109/L | 3.68 ±2.45 | 2.2 ± 1.7 | .038 | — | — | — | — |

| RBCs and EVs | RBCs and EVs | ||||||

| PS+RBC, % | 0.25 ± 0.14 | 0.19 ± 0.16 | .066 | Oxidative hemolysis, mg/dL | 14.9 ± 11.7 | 7.5 ± 5.3 | .031 |

| TR-like PPA, RFU | 40655 ± 10182 | 48410 ± 13056 | .061 | Osmotic hemolysis, 24 hours, MCF, NaCl% | 0.506 ± 0.033 | 0.481 ± 0.034 | .051 |

| Procoagulant phospholipid activity, % | 13. 0 ± 7.0 | 7.3 ± 3.8 | .032 | CH-like PPA, m, RFU | 31349 ± 15009 | 59887 ± 37743 | .032 |

| Supernatant metabolites | Supernatant metabolites | ||||||

| Dimethyl-arginine | 4.67 ± 1.10 | 4.29 ± 1.65 | .079 | L-Arginine | 0.067± 0.108 | 0.117 ± 0.201 | .065 |

| Dopamine | 4.75 ± 2.10 | 3.81 ± 1.53 | .084 | L-Homocysteine | 0.001 ± 0.003 | 0.004 ± 0.006 | .045 |

| Norepinephrine | 1.49 ± 0.62 | 1.19 ± 0.49 | .022 | Melatonin | 1.41 ± 1.15 | 0.63 ± 0.83 | .018 |

| Normetanephrine | 31.82 ± 6.74 | 27.56 ± 7.77 | .009 | Thiamine monophosphate | 0.084 ± 0.088 | 0.139 ± 0.087 | .020 |

| Glutaryl-L-carnitine | 4.46 ± 3.14 | 2.80 ± 2.59 | .069 | Phthalic acid | 43.01 ± 28.92 | 29.58 ± 25.39 | .017 |

| 2-Amino-isobutyric acid | 0.127 ± 0.042 | 0.102 ± 0.042 | .038 | MEHP | 14.20 ± 8.76 | 10.13 ± 7.75 | .020 |

| — | — | — | — | MMP | 0.290 ± 0.474 | 0.140 ± 0.248 | .037 |

| — | — | — | — | d-Lactose | 0.298 ± 0.122 | 0.259 ± 0.204 | .037 |

Independent t test or Mann-Whitney U (2 samples) test. Metabolites: normalized values.

Bold: higher values between high- and low-ΔHb groups.

CH, chymotrypsin; INR, international normalized ratio; m; membrane; MCF, mean corpuscular fragility; MiNP, monoisononyl phthalate; MON, monocyte; NEU, neutrophil; RFU, relative fluorescence units; TR, trypsin.

In univariate analysis (Figure 3B), ΔHbpost correlated with several patient variables, including sex (higher in women), mutation severity, baseline anemia (positive), disease complications (negative), total RBC volume (negative), baseline RET/NRBC counts (negative), lactate dehydrogenase, PS+ RBCs (negative), plasma amino acids (positive), and acylcarnitine levels (negative). Fewer component variables correlated with ΔHbpost, such as residual platelet count (negative), RBC PPA (positive), supernatant normetanephrine (negative), and, again, acylcarnitines (supplemental Table 4). An ANOCOVA, controlling for sex, showed significant effects of baseline RBC and NRBC counts, NLR index, and age of transfusion initiation on ΔHbpost. Among these, NLR emerged as the strongest determinant (F = 16.78, P = .010), after adjusting for mutation severity and baseline Hb levels. The corresponding ROC curve yielded an area under the curve of 0.7750 (supplemental Figure 5A), suggesting a good discriminatory power for the NLR model in distinguishing between high/low ΔHbpost events.

With respect to later transfusion response (ΔHbweek), high responders had greater baseline anemia, fewer PS+ RBCs, near-normal PT/International Normalized Ratio (INR) values, as well as elevated α2-macroglobulin and oxoproline levels vs poor responders (Table 4). Additional posttransfusion differences between high/low responders are shown in supplemental Table 5. RBC units delivered to the high-ΔHbweek group had lower oxidative and osmotic hemolysis but higher RBC membrane-specific PPA (Table 4). Supernatants showed increased vitamin B1 and trends (P = .055) toward elevated L-arginine but lower DEHP metabolite levels. ΔHbweek was not influenced by transfusion dose.

Univariate analysis (Figure 3C; supplemental Table 6) revealed significant correlations for ΔHbweek with recipient sex (higher in women), total blood volume, total RBC volume, baseline Hb, and monocyte levels (all negative). Notably, PS+ RBCs in addition to plasma glycocholic acid and acylcarnitine levels negatively correlated with ΔHbweek, as they did with ΔHbpost. Component volume, antioxidants, membrane PPA, and sex mismatching (mostly female recipients of male-derived units, n = 22) correlated positively with ΔHbweek, in contrast to the oxidative hemolysis and PS exposure. Reverse mismatching (male recipients of female-derived units) could lead to smaller ΔHbs.2 Multivariate ANOCOVA confirmed that patient sex, pretransfusion Hb, PS-exposing donor and recipient RBCs, in addition to UA-dependent antioxidant capacity of components, significantly influenced ΔHbweek. Even after adjusting for sex and pretransfusion Hb, these unit variables remained significant influencing factors (eg, F = 14.18, P = .001 for UA-dependent antioxidants) for ΔHbweek. In combination with the patient baseline PS+RBC percentage, these unit variables yielded an area under the curve of 0.7889 in ROC logistic regression modeling (supplemental Figure 5B).

Discussion

This linked donor-recipient study determined the kinetics of blood physiology features after transfusion, and highlighted factors that influence ΔHb. The findings differ, in some points, from those reported in other recipient settings, including patients who are critically ill or have experienced trauma and patients with cancer.

Kinetics of blood and RBC physiological features after transfusion

There is evidence that transfusion improves the thrombotic risk and endothelium dysfunction markers in patients with TDT and SCD.42,43 Our findings indicate that these beneficial effects persist beyond immediate dilution shortly after transfusion, likely due to enhanced oxygen delivery and reduced erythropoietin levels.44 Additionally, sex mismatching showed no severe impact on endothelial activation in our cohort compared with patients who are critically ill.45 Increase in the ratio of red cell distribution width to platelets reflects a reduced platelet count rather than inflammation, as suggested by the high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, NLR, and WBC metrics. Although leukocytosis has been reported after transfusion with nonleukoreduced46 or older47 RBC units, we observed opposite variation in the 1-week time point, suggesting reduced bone marrow stress or inflammation in response to adequate transfusion with leukoreduced and short-stored RBCs.

Hepcidin (which integrates erythropoietic activity, iron kinetics, and circulating RBCs27) typically rises after transfusion due to iron overload.48 Consistent with this,27 we observed a hepcidin increase at the 1-week mark of maximal erythroid suppression (confirmed by the sharp drop in RET and NRBC counts). The currently observed effect of transfusion dose on hepcidin rise (smaller with lower transfusion volumes), aligns with findings of lower posttransfusion hepcidin levels in male patients with TDT (who received proportionally smaller RBC volumes) than female patients with TDT.27

The expected14 transient rise in cell-free Hb (Figure 1B) may exacerbate oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction, and should probably be monitoring in patients with cardiovascular comorbidities or low haptoglobin. However, it was efficiently cleared by the patient’s scavenging systems within a week. The positive correlation with storage hemolysis seen in 2-unit (but not 1-unit) transfusions suggests that larger doses may overwhelm the patient’s capacity to buffer cell-free Hb, raising the risk of toxicity. Note, despite the high osmotic and oxidative hemolysis of stored RBCs, no increase was detected in patients with TDT after transfusion, suggesting a protective effect of TDT plasma (ie, enriched with antioxidants; Table 3) on donor RBCs. In contrast, no such protective effect was shown for mechanical hemolysis. Although plasma from healthy controls,49 or patients with uremia (rich in erythropoietin and UA)50 has shown cytoprotective effects on stored RBCs under recipient-mimicking conditions in vitro, mechanical hemolysis followed an opposite trend,49 consistent with our current in vivo findings in thalassemic plasma. The subsequent drop of mechanical hemolysis below both baseline and healthy control levels25 (shaded area in Figure 1B) 1-week after transfusion indicates significant changes in RBC membrane/skeletal architecture. This modification likely stems from multiple contributing factors.

On one hand, transfusion improves the oxidative state and oxygen-carrying capacity of Hb,51 as well as plasma rheology and the metabolome (fatty acids,52 carnitine, amino acids, glutamine,53 etc; Figure 2B). Supplementing these metabolites has been shown to improve RBC deformability ex vivo,53 and in patients with TDT,54 and SCD.55 For example, posttransfusion rise in glutamine (a precursor of glutathione and arginine), may lower RBC oxidative stress, and boost nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability in the vasculature.56 On the other hand, the increased mechanical resistance of TDT RBCs compared with healthy controls (mechanical fragility index of 0.663 ± 0.161 vs 0.816 ± 0.181%, respectively, P = .008) may reflect cellular dehydration and higher density,57 driven by oxidative damage to membrane components,58 as suggested by the kinetics of membrane-bound hemichromes (Table 3). In patients who have undergone splenectomy, these rigid RBCs likely persist longer in circulation.59 The complexity of metabolic networks aligns with these simultaneous, opposing effects, as shown in a recent glutamine trial in SCD, that showed marked RBC dehydration despite improved oxidative stress and deformability.60 Overall, our findings underscore significant variations in the mechanical properties of TDT RBCs across transfusion and erythropoiesis cycles, which may contribute to impaired oxygen delivery and increased vascular resistance61 between transfusions.

Consistent with previous studies in pediatric TDT showing posttransfusion increases in serum oxidants/antioxidants,62 we found alterations in the redox status of plasma and RBCs later after transfusion. More importantly, despite the poor cytosolic PPA in TDT RBCs compared with healthy controls,25 we observed a delayed increase in membrane PPA after transfusion. This might reflect reduced heme toxicity on membrane proteasomes,63 or an adaptive response to accumulated globin chains and damaged proteins (Table 3), enabling TDT RBCs to function despite oxidative stress. Elevated PPA could help clear or modify mildly defected yet flexible membrane proteins, ultimately leaving a stiffer, mechanically resistant membrane. The associations between membrane PPA, spleen status, and transfusion dose underscore the role of proteostasis in maintaining membrane integrity under mechanical stress,64 and may also reflect storage lesion, as a cytosol-to-membrane PPA shift has been documented in stored RBCs.65

Finally, the transfusion-driven increase in plasma metabolites (eg, L-arginine; Figure 2A), which are typically low in patients with TDT,25 is expected to benefit not only the endothelial status41 but also the RBC integrity and function.53 Similarly, the currently observed increase in deoxyadenosine by transfusion may support hypoxic adaptation and stimulate 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate (2,3-BPG) production,66 enhancing oxygen delivery to tissues. It is thus unsurprising that RBC NO levels are elevated in patents with β-thalassemia/HbE 1 week after transfusion.67

Transfusion also temporarily increased circulating DEHP plasticizer metabolites (Figure 2) that leach from blood units.41,68 Although their levels returned to baseline within a week, the increase may still pose health risks.69 Notably, single- and double-unit transfusions showed similar phthalate levels shortly after transfusion (likely due to the short storage duration70), but single-unit recipients exhibited lower 1-week levels, suggesting ongoing metabolism. In contrast, other phthalates derived from plasticizers in materials beyond blood bags did not normalize within a week. Their presence in TDT plasma may reflect donor (MMP; Figure 2B) and/or patient (mono-[carboxy-iso-octyl] phthalate) environmental exposure or slower degradation, raising potential toxicity concerns, including oxidative stress in RBCs.71 These findings highlight the need for further research into the effects of phthalates in patients with TDT.

ΔHb varies greatly between patients at both posttransfusion time points

The effect of recipient factors on ΔHb

We found significant deviations from the historical ΔHb target of 1 g/dL,72 with some patients even dropping below baseline a week after transfusion. Female sex and baseline anemia2,7,8,11,12 have consistently been linked to higher ΔHb across various recipient settings. However, the role of spleen status in TDT remains unclear.14 Our data show that the same transfusion dose affects ΔHb differently, depending on anemia, erythropoietic stress, and hemolysis/disease severity. Although pretransfusion Hb influences both ΔHb measures, further research is needed to assess whether transfusing patients with TDT at more advanced anemia could be advantageous, balancing donor exposure risks against anemia tolerance.

ΔHbpost was more strongly linked to baseline recipient variables than ΔHbweek. NLR emerged as a determinant of ΔHbpost after adjusting for baseline anemia and other confounders. In TDT, immune dysregulation and low-grade inflammation, driven by hemolysis and iron overload,47 can suppress erythropoiesis, increase hepcidin-mediated iron sequestration (further affected by transfusion), strain vascular function and oxidative stress, and promote erythrophagocytosis. Inflammation has thus been associated with lower ΔHbs in hematological conditions.73 Because NLR reflects the balance between immune responses and systemic inflammation, a lower NLR suggests more balanced responses, and fewer TDT-associated immunosenescent neutrophils.74 NLR is considered a prognostic marker of mortality in patients with severe hemorrhage managed with massive transfusion protocol.75 Monitoring NLR and addressing systemic inflammation before transfusion may help enhance transfusion outcomes.

In addition to other ΔHb modifiers, “good responders” showed lower baseline hypercoagulability, as indicated by the PS+ RBCs, soluble von Willebrand factor antigen, free protein S, and EV metrics. Hypercoagulability can hinder recovery of transfused RBCs by promoting adhesion to the endothelium and splenic clearance. Elevated α2-macroglobulin (possibly reflecting better liver function) may alleviate inflammation through cytokine neutralization, and maintain extracellular proteostasis by targeting hemolysis products,76 thus lowering systemic inflammation and oxidative stress.

Better transfusion responses in patients with TDT were also linked to baseline plasma metabolite variations, including methionine, adenosine, and bile acids (ΔHbpost). Methionine may indicate protein repair in stressed RBCs,70 and adenosine the transfusion burden, release from damaged cells,77 or a hypoxia-driven metabolic adaptation through purinergic signaling,78 which also influences erythropoiesis.79 Elevated baseline 5-oxoproline in good ΔHbweek responders suggests altered γ-glutamyl cycle activity, important for glutathione metabolism and redox balance. Conversely, higher baseline acylcarnitine levels were negatively associated with ΔHbpost and ΔHbweek, in consistency with their role in proinflammatory signaling80 and cardiovascular dysfunction.81

The effect of donor/blood component factors on ΔHb

In our cohort, ΔHbpost was linked to RBC unit variations in residual platelets, acylcarnitines, dimethyl-arginine, and catecholamines. The acylcarnitine connections support the protective role of carnitine pools against storage hemolysis, by promoting lipid peroxidation repair. Indeed, the REDS study showed greater ΔHbs after transfusions with high carnitine units at prolonged storage.82 Activation of donor platelets and release of biological response modifiers (proinflammatory cytokines, reactive oxygen species, EV) reduce RBC unit quality, trigger local inflammation, and impair recovery of transfused RBCs. Of note, platelets and leukocytes are key sources of damage-associated molecular patterns, particularly in shorter-stored units.20 These factors, along with donor variables and storage hemolysis,83 influence catecholamine levels in RBC units. Besides stimulating adrenergic receptors and promoting RBC adherence in SCD,84 catecholamines were associated with lower ΔHb in this study, suggesting their potential as markers of poor storability. They may also contribute to adverse transfusion outcomes by promoting vasoconstriction, platelet activation,85 redox imbalance,86 immunomodulation,87 and reduced RBC deformability,5 all increasing RBC clearance. Additionally, dimethyl-arginine, a marker of storage lesion and potent inhibitor of NO synthase has been linked to hemolysis and breakdown of arginine-methylated proteins during storage. In recipients with TDT, who already face disrupted NO metabolism due to hemolysis, further NO inhibition could worsen endothelial dysfunction and RBC abnormalities.

According to our results (Figure 3; Table 4), arginine metabolism and RBC proteasome activity significantly affect both ΔHb measures, whereas RBC storage lesions (eg, oxidative hemolysis and phthalates) more strongly affect ΔHbweek. Specifically, RBCs with a greater capacity to handle storage-induced protein damages appear to support better outcomes. Donor RBC susceptibility to hemolysis likely affects their long-term recovery in TDT circulation, as shown by large-scale retrospective studies linking donor genetic variants associated with osmotic and oxidative hemolysis to transfusion efficacy.7,88

To our knowledge, for the first time, we identified a negative correlation between RBC unit phthalate levels and ΔHb in TDT. Despite stabilizing effects of DEHP on RBC membrane that minimize storage hemolysis,89 DEHP metabolites carry risks, including triggering proinflammatory cytokine release,90 and endocrine disruption.91 Elevated DEHP metabolites indicate prolonged storage and poorer RBC quality,92 resulting in lower posttransfusion recovery. Of note, this storage variable is donor specific.92

More importantly, phthalate burden on ΔHb extends beyond DEHP to other esters, such as MMP, a breakdown product of dimethyl-phthalate, commonly found in consumer products. Elevated MMP levels in RBC units suggest recent environmental exposure of donors. Although dimethyl-phthalate and MMP are considered less toxic than DEHP, their emerging RBC toxicity71 and impact on transfusion efficacy highlight the need for comprehensive studies of donor and TDT exposomes to better optimize transfusion outcomes.

Finally, PS exposure and the UA-dependent antioxidant capacity of the units emerged as influencers of ΔHbweek, after adjusting for patient sex and baseline anemia. Both variables reflect the severity of storage lesion, and are influenced by donor factors and unit preparation methods.35 PS-exposing RBCs have a shorter life span, and show increased procoagulant activity and adhesiveness, whereas UA-dependent antioxidant capacity helps counter oxidative damage39 and storage lesion.93 Our findings suggest that high-quality donor RBCs achieve better recovery in the antioxidant-rich TDT plasma, whereas lower-quality RBCs benefit less. PS exposure and UA-dependent antioxidant capacity can be easily assessed at the point of care, providing practical tools to optimize transfusion efficacy by guiding unit selection and storage strategies. Because the maximum storage duration of RBC units in this study was 26 days (supplemental Figure 4; Table 1), we found no effect of storage duration on ΔHb. Notably, longer storage durations (>35 days) have been linked to reduced ΔHbs.2,7,10

Overall, these findings highlight the intricate relationship between donor/patient exposures and storage lesions with transfusion outcomes. They underscore the importance of understanding the environmental and biological factors that influence RBC unit quality and their clinical impact in patients with TDT. Considering these factors will be essential for future studies examining how donor/component and patient characteristics, including genetic polymorphisms, affect posttransfusion ΔHb and other outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients who voluntarily participated in this study; the clinical-laboratory staff of the collaborating hospitals “Hippokration,” “Laikon,” and “Aretaieio” (School of Medicine) for blood sampling, fractionation, and assistance in serum biochemical testing; the graduate and postgraduate students Evgenia Kazolia, Vassiliki Chaidou, Vasiliki-Zoe Arvaniti, Aggeliki-Aikaterini Kondi, Elina Vasilakou, Vassiliki Kourkouva, Antonia Dourouki, and Stamatia-Efthymia Rodi for participation in part of the experiments; Artemis Voulgaridou for assistance in network analyses; and George Kastaniotis for assistance in data analysis. Aggeliki Panagopoulou is particularly acknowledged for supporting the RBC Biology Laboratory of National and Kapodistrian University of Athens (NKUA). The authors also acknowledge the postgraduate program “Thrombosis, Bleeding, and Transfusion Medicine” of the School of Medicine of NKUA for supporting this research.

This work has been financially supported, in part, by the donation grant NKUA/Special Account for Research Grants no. 20241/2023 (M.H.A.).

Authorship

Contribution: S.D., M.P., V.K., E.V., and M.H.A. conceptualized and designed the study; S.D., E.V., V.K., and M.M. recruited volunteers and made the clinical evaluation; M.H.A. coordinated the research; K.T. and M.H.A wrote the manuscript and made the figures; K.T., I.B., A.T.A., V.L.T., S.R., G.T., I.V.K., E.I.K., T.G., and E.P. performed the experiments; K.T., I.B., G.T., N.S., E.G., E.-A.S., and M.H.A. analyzed the results; and V.L.T., K.S., E.N., O.T., N.V., N.T., and E.G. contributed to the implementation of the research.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for A.T.A. is Department of Biochemistry, School of Medicine, University of Patras, Patras, Greece.

The current affiliation for V.L.T. is Department of Biochemistry, School of Medicine, University of Patras, Patras, Greece.

The current affiliation for V.K. is Laboratory of Hematology, Gennimatas General Hospital, Athens, Greece.

Efthymia Ioanna Koufogeorgou died on 25 April 2025.

Correspondence: Marianna H. Antonelou, Department of Biology, School of Science, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Zografou University Campus, Panepistimiopolis, Zografou, 157 84 Athens, Greece; email: manton@biol.uoa.gr.

References

Author notes

The materials, data sets, and protocols are available to other investigators from the corresponding author, Marianna H. Antonelou (manton@biol.uoa.gr), without unreasonable restrictions.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

![Variation in plasma metabolites across transfusion time. (A) Heat map showing the mean differential expression of the top 60 metabolites identified by targeted metabolomics across time points. (B) Summary of TDT metabolites that changed significantly (fold change vs before; P < .05) in the posttransfusion period (Post, Week), based on ANOVA with post hoc tests. Fold change levels (vs before [Pre]) in RBC unit supernatants are also presented. Red tones, increase; blue tone, decrease. The metabolites are classified in 3 groups based on their response to transfusion: those showing reversible early response, irreversible early response, or late response. Representative examples are shown in the box plots (C-E), denoting the normalized (cube root transformation) and scaled (autoscaling) peak areas of metabolites with pronounced differences between the 3 timepoints. The bars of the box plots depict the median along with the interquartile range. ∗P < .05 vs before; #P < .05 vs after. 2-ABA, 2-amino-isobutyrate; GABA, γ-aminobutyrate; MCiOP, mono-(carboxy-iso-octyl) phthalate; MiNP, monoisononyl phthalate.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/bloodadvances/10/1/10.1182_bloodadvances.2025017090/1/m_blooda_adv-2025-017090-gr2.jpeg?Expires=1770417524&Signature=PmAtnz8Pu1uhtPNfyqjy1afP9mvBhW7GBg8WuVItPHwuD44ObO8z0kP-UoQCrKq3EWNA6Hxkho2q~DlNsB4OqczLHupOdLaPOjUtoUc3MuRqz0qw6wwltX5E2-KrmF1lM3ehwJFbnHjLLYcLqIjQvaZWlW11RbHORONMyoPH2maSfDiKljNVAmBjri1knBSZdaHxes2uXnLJqL6BbFX7es1AhVKgUBA0PplFLjHw5s2X5GBAeYF3UIBO51lvDwrtpgXOkNaTiLZz5PloHqTOSWOeHd~87UXcnYQHlVds6jDbGht~z4Q9r~wOiRbK1mYCmnQ~aZjUHHOHpBm~6idoNw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)