A recombinant anti-CD25 immunotoxin, LMB-2, has shown clinical efficacy in hairy cell leukemia and T-cell neoplasms. Its activity in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B-CLL) is inferior but might be improved if B-CLL cells expressed higher numbers of CD25 binding sites. It was recently reported that DSP30, a phosphorothioate CpG-oligodeoxynucleotide (CpG-ODN) induces immunogenicity of B-CLL cells by up-regulation of CD25 and other antigens. The present study investigated the antitumor activity of LMB-2 in the presence of DSP30. To this end, B-CLL cells from peripheral blood of patients were isolated immunomagnetically to more than 98% purity. Incubation with DSP30 for 48 hours augmented CD25 expression in 14 of 15 B-CLL samples, as assessed by flow cytometry. DSP30 increased LMB-2 cytotoxicity dose dependently whereas a control ODN with no CpG motif did not. LMB-2 displayed no antitumor cell activity in the absence of CpG-ODN as determined colorimetrically with an (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium, inner salt (MTS) assay. In contrast, B-CLL growth was inhibited in 12 of 13 samples with 50% inhibition concentrations (IC50) in the range of LMB-2 plasma levels achieved in clinical studies. Two samples were not evaluable because of spontaneous B-CLL cell death in the presence of DSP30. Control experiments with an immunotoxin that does not recognize hematopoietic cells, and an anti-CD22 immunotoxin, confirmed that sensitization to LMB-2 was specifically due to up-regulation of CD25. LMB-2 was much less toxic to normal B and T lymphocytes compared with B-CLL cells. In summary, immunostimulatory CpG-ODNs efficiently sensitize B-CLL cells to a recombinant immunotoxin by modulation of its target. This new treatment strategy deserves further attention.

Introduction

B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B-CLL) is the most common type of leukemia in the Western hemisphere, accounting for 25% of all leukemias.1 Of CLL cases in the United States, 95% are of B-cell origin.1 This disease is characterized by progressive accumulation of B cells with very low proliferative capacity but prolonged cell survival.2 It has, therefore, been suggested that mechanisms of physiologic cell death are impaired in B-CLL cells.3

Patients whose normal hematopoiesis is compromised by leukemic infiltration of bone marrow or by disease-related disorders of the immune system require treatment. Standard treatment involves anticancer drugs such as fludarabine, chlorambucil, and corticosteroids (reviewed in Wendtner et al4). However, despite high-dose chemotherapy with stem cell support and the introduction of new chemotherapeutic agents, treatment is rarely curative, and most patients will eventually die from complications of CLL.4 5Thus, new therapeutic options are needed.

Targeted therapies with monoclonal antibodies or immunotoxins have been introduced into the clinic in recent years. Monoclonal antibodies to B-cell antigens can induce clinical remissions in non-Hodgkin lymphomas, including B-CLL.6 Immunotoxins contain a protein toxin, which causes cell death upon internalization into cells, in addition to a targeting monoclonal antibody or a fragment thereof, or a ligand for cellular receptors (for review see Pastan and FitzGerald7 and Frankel et al8).

A recombinant immunotoxin, anti-Tac(Fv)–PE38 (LMB-2), which is directed against the α-chain of the interleukin-2 receptor (also referred to as Tac or CD25 antigen), has been investigated in patients with malignant lymphomas.9,10 In a recent phase I study, LMB-2 has induced major responses in 4 of 4 patients suffering from previously refractory hairy cell leukemia (HCL), including a lasting complete remission.9 Furthermore, remissions were observed in T-cell lymphoma, adult T-cell leukemia, CLL, and Hodgkin disease.10 LMB-2 was less active in CLL than in HCL with only one of 8 patients with CLL responding to treatment.10

LMB-2 is a single-chain immunotoxin composed of the variable heavy domain region of a monoclonal antibody, anti-Tac,11 fused via a 15–amino acid linker to the variable light domain, which in turn is fused to PE38, a truncated form of Pseudomonasexotoxin.12,13 Truncated toxins such as PE38 are internalized only after binding to target cell protein.14,15Pseudomonas exotoxin and immunotoxins containing PE38 cause cell death by inhibition of protein synthesis due to inactivation of elongation factor 2.16,17The mode of cytotoxicity includes binding of the immunotoxin to CD25, internalization and processing of the toxin within its translocation domain,18 binding of the 35-kd carboxy-terminus of the toxin intracellularly to the KDEL receptor that carries it to the endoplasmatic reticulum,19 translocation of the toxin into the cytosol,20,21 and catalytic adenosine diphosphate (ADP)–ribosylation of elongation factor 2.16,17 As a result of inhibition of protein synthesis, apoptosis and cell death are induced.22 In addition, LMB-2 can kill cells without induction of caspase-dependent apoptosis.22

In preclinical studies performed in murine xenograft models, LMB-2 has shown high cytotoxic activity against tumor cells that express CD25.13 Furthermore, freshly isolated cells from adult human T-cell leukemia are very sensitive to this immunotoxin in tissue culture.23,24 HCL is particularly sensitive to LMB-2, mainly because these cells express very high levels of the respective antigen, CD25.25 However, LMB-2 is not as toxic to CLL samples.26 The numbers of CD25 sites per cell are considerably lower in B-CLL compared with HCL.25

Expression of surface antigens on B cells is not invariant, but is modulated upon activation during the process of immune response. Bacterial DNA and mimicking synthetic ODN sequences possess immunostimulatory properties as recently recognized (for review see Wagner27 and Krieg and Wagner28). Unmethylated CpG dinucleotide motifs are present at the expected frequency (1 in 16) in bacterial DNA, whereas CpG dinucleotides are suppressed and methylated in mammalian DNA.29 Thereby, cells of the immune system are enabled to distinguish bacterial DNA from self-DNA. This leads to the initiation of inflammatory responses. Bacterial DNA and ODNs containing an unmethylated CpG motif activate monocytes,30 dendritic cells,31 and B cells.32,33 CpG-ODNs have been demonstrated to be effective adjuvants in tumor antigen immunization.34,35Furthermore, they can enhance the antitumor response to monoclonal antibody therapy of lymphoma.36 CpG-ODNs are currently being evaluated in clinical phase I/II studies in this setting.37

We have recently reported that B-CLL cells are also stimulated by treatment with an ODN containing a CpG-dinucleotide.38This CpG-ODN, DSP30, leads to proliferation of B-CLL cells, furthermore to cytokine production and up-regulation of cell surface molecules including CD40, CD54, CD80, CD86, and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules.39 Up-regulation of functional interleukin-2 receptors increases the immunogenicity of leukemic cells in the presence of interleukin-2.39

In the present work, we investigate whether up-regulation of CD25 increases the antileukemic efficacy of the immunotoxin LMB-2 in B-CLL. We find that exposure to a CpG-ODN renders primary B-CLL cells from peripheral blood of patients better targets for treatment with the immunotoxin. Thereby, the majority of unresponsive B-CLL cell samples are sensitized to LMB-2 at concentrations that are achievable in patients. In contrast, the cytotoxicity of LMB-2 toward normal B and T lymphocytes is only slightly increased upon concomitant treatment with the CpG-ODN.

Patients, materials, and methods

Patients and immunomagnetic separation of B-CLL cell samples

Following informed consent, peripheral blood was obtained from patients with confirmed B-CLL. B-CLL was diagnosed according to morphologic and immunophenotypic criteria as described elsewhere.40 Patient characteristics and prior treatment are shown in Table 1. Patients were either untreated or had not received cytoreductive chemotherapy for at least 3 months prior to blood collection. By the time of analysis, all patients were clinically stable and free from infectious complications. For control experiments, tonsil tissue samples were collected from consenting patients undergoing tonsillectomy for nonmalignant disease.

Patient characteristics

| No. . | Sex . | Age . | White blood count × 109/L . | Binet stage . | Previous therapies . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 77 | 144 | B | 2 |

| 2 | M | 52 | 63 | C | 5 |

| 3 | M | 81 | 56 | C | 2 |

| 4 | M | 65 | 120 | C | 0 |

| 5 | F | 74 | 22 | A | 0 |

| 6 | M | 64 | 133 | B | 4 |

| 7 | M | 71 | 39 | B | 0 |

| 8 | F | 67 | 181 | A | 0 |

| 9 | M | 81 | 56 | C | 2 |

| 10 | F | 82 | 86 | A | 0 |

| 11 | M | 79 | 48 | B | 1 |

| 12 | F | 64 | 16 | B | 2 |

| 13 | F | 81 | 205 | B | 0 |

| 14 | M | 33 | 75 | B | 0 |

| 15 | F | 65 | 54 | C | 3 |

| No. . | Sex . | Age . | White blood count × 109/L . | Binet stage . | Previous therapies . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 77 | 144 | B | 2 |

| 2 | M | 52 | 63 | C | 5 |

| 3 | M | 81 | 56 | C | 2 |

| 4 | M | 65 | 120 | C | 0 |

| 5 | F | 74 | 22 | A | 0 |

| 6 | M | 64 | 133 | B | 4 |

| 7 | M | 71 | 39 | B | 0 |

| 8 | F | 67 | 181 | A | 0 |

| 9 | M | 81 | 56 | C | 2 |

| 10 | F | 82 | 86 | A | 0 |

| 11 | M | 79 | 48 | B | 1 |

| 12 | F | 64 | 16 | B | 2 |

| 13 | F | 81 | 205 | B | 0 |

| 14 | M | 33 | 75 | B | 0 |

| 15 | F | 65 | 54 | C | 3 |

Enrichment of B-CLL cells by density gradient centrifugation over a Ficoll-Hypaque layer and immunomagnetic depletion of T lymphocytes and monocytes has been described.39 The content of CD19+ cells was more than 98% pure in the immunoseparated cell samples. Similarly, tonsillar B cells were enriched as described for B-CLL cells, resulting in a purity of more than 95% CD19+ cells. T cells were purified from peripheral blood by depletion of B lymphocytes and monocytes as described.39

Cells were immediately used for further experiments or resuspended in fetal calf serum (FCS) with 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and stored in liquid nitrogen until use. Control experiments demonstrated similar results when frozen or fresh cells from the same sample were used.

Reagents, antibodies, immunotoxins, and cell lines

All ODNs were synthesized by TibMolBiol (Berlin, Germany). The sequence of DSP30 (TCGTCGCTGTCTCCGCTTCTTCTTGCC), a single-stranded, phosphorothioate-stabilized ODN has been reported.33 PZ27 (CCCCTCCTAGTGGGGGTGTCCTATCCC) is a 27-mer modification of a sequence designated pZ2,41 whereas C27 consists solely of cytosine residues. All ODNs were used at 1 μM unless indicated otherwise.

Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated monoclonal antibodies to CD3, CD19, CD22, and CD25, as well as the appropriate isotype control were purchased from Beckman Coulter-Immunotech (Krefeld, Germany). The immunotoxins LMB-2 (also designated anti-Tac(Fv)–PE38, directed to the CD25 antigen), BL22 (RFB4(dsFv)-PE38, specific for CD22), and LMB-9 (B3(dsFv)-PE38, specific for a LewisY antigen) were developed and produced as described.19 42-44 The immunotoxins were diluted in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) to stock concentrations of 480 μg/mL (LMB-2), 960 μg/mL (LMB-9), and 763 μg/mL (BL22), and stored as aliquots at −80°C until they were used in experiments.

Culture conditions and proliferation assay

Purified normal or leukemic B cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Biochrom, Berlin, Germany) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Biochrom), 50 IU/mL penicillin/streptomycin, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, L-glutamine at 2 mM, 20 μg/mL L-asparagine, 0.05 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 10 mM HEPES, and MEM nonessential amino acids 0.7x (Biochrom). All tissue culture experiments were performed at 37°C and 5% CO2 in a fully humidified atmosphere in 96-well plates at 3 × 105 cells in a total volume of 100 μL for 5 days. At the end of the culture period, an (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium, inner salt (MTS) assay was performed: 10 μL of a combined MTS/phenazine methosulfate (PMS) solution (Promega, Mannheim, Germany) was added, and the optical density at 490 nm (OD490) was determined using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) reader. Mean values were calculated from triplicate cultures. To correct for background activity, cells were cultured in the presence of cycloheximide (Sigma) at 10 μg/mL. Results are depicted as the percentage of OD in comparison with cells cultured in the absence of immunotoxin. This was calculated using the following equation: (OD490 of cells without immunotoxin − OD490 of cells cultured with cycloheximide)/(OD490 of cells cultured in the presence of immunotoxin/− OD490 of cells cultured with cycloheximide). Data from individual experiments are presented as mean plus or minus SEM. We confirmed our results with the trypan blue exclusion method in 2 independent samples.

Immunophenotyping

Cells were washed in PBS containing 2% FCS and incubated with saturating amounts of fluorochrome-conjugated monoclonal antibody or an equal amount of a nonbinding, isotype-identical control antibody. Fluorochromes were either FITC or phycoerythrin (PE). After 30 minutes at 4°C, cells were washed with PBS/2% FCS and analyzed via flow cytometry using a Coulter Epics XL cytofluorometer, acquiring 10 000 events. Data were analyzed using WinMDI 2.8 FACS software. The relative expression of surface antigen is described as the mean fluorescence intensity ratio. This value equals the mean fluorescence intensity of cells stained with a fluorochrome-conjugated antigen-specific antibody, divided by the mean fluorescence intensity of cells stained with a fluorochrome-conjugated isotype control antibody.

Results

Up-regulation of CD25 expression by immunostimulatory ODNs

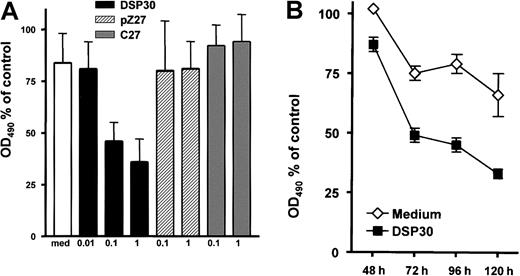

B-CLL cells in peripheral blood of patients expressed low amounts of the CD25 antigen (Figure 1A). Upon a 2-day exposure to ODN DSP30, which contained a CpG motif, CD25 expression was up-regulated in a dose-dependent fashion. At 0.1 μM of DSP30, anti-CD25 fluorescence intensity was increased more than 10-fold with a further increase at 1 μM. In contrast, pZ27, a control ODN with no CpG motif, failed to increase CD25 expression at 0.1 μM and displayed only minor effects at 1 μM. C27, a phosphorothioate ODN, was used as a control to exclude that a nonspecific immunostimulatory effect of the backbone was responsible for the observed effect. No up-regulation of CD25 was observed even at 1 μM (Figure 1A). CD25 up-regulation could be detected after 8 hours of culture with DSP30, but longer incubation periods (48 hours to 72 hours) are needed for maximal up-regulation (Figure 1B).

CD25 expression in B-CLL cells treated with ODN.

(A) 1 × 106 purified B-CLL cells were incubated for 48 hours with DSP30, pZ27, or C27 at indicated concentrations. Cells were stained and analyzed by flow cytometry as described in the text. Histograms show fluorescence intensities of the anti-CD25 antibody (shaded), superimposed with that of an isotype control (solid line). Shown is a representative experiment; 2 additional experiments gave similar results. (B) CD25 expression is shown in one sample during a time course of 72 hours in the presence of 1 μM DSP30. Similar results were observed in an independent experiment. (C) Expression of CD25 in B-CLL samples from individual patient’s cells after 48 hours in tissue culture in the presence (black bars) or in the absence (gray bars) of DSP30.

CD25 expression in B-CLL cells treated with ODN.

(A) 1 × 106 purified B-CLL cells were incubated for 48 hours with DSP30, pZ27, or C27 at indicated concentrations. Cells were stained and analyzed by flow cytometry as described in the text. Histograms show fluorescence intensities of the anti-CD25 antibody (shaded), superimposed with that of an isotype control (solid line). Shown is a representative experiment; 2 additional experiments gave similar results. (B) CD25 expression is shown in one sample during a time course of 72 hours in the presence of 1 μM DSP30. Similar results were observed in an independent experiment. (C) Expression of CD25 in B-CLL samples from individual patient’s cells after 48 hours in tissue culture in the presence (black bars) or in the absence (gray bars) of DSP30.

An overview of all patient samples tested is displayed in Figure 1C. CD25 expression was markedly induced in 12 of 13 (92%) of the samples. In only one sample was no CD25 up-regulation observed. The relative increase, however, varied from one patient to another. Two samples (patient no. 8 and patient no. 12) could not be evaluated because the CLL cells died in the presence of DSP30 (cell viability reduced to 13% and 26% of control, respectively, in the presence of DSP30 without immunotoxin).

Sensitization of B-CLL cells to LMB-2 immunotoxin by DSP30

B-CLL cells were incubated for 5 days with LMB-2 at 1 μg/mL and various concentrations of DSP30, pZ27, or C27. Thereafter, cell viability was assessed colorimetrically with an MTS assay. As shown in Figure 2A, the cytotoxicity of LMB-2 was increased upon addition of DSP30. Sensitization by DSP30 was dose dependent with a maximum effect at 1 μM. It should be noted that DSP30 exerted no cytotoxic effect in B-CLL cells from these patients if LMB-2 was not added. DSP30 caused a moderate increase of cell viability in the absence of LMB-2 (average: 40% increase in OD490 in 15 patient samples). Thus, the interaction of DSP30 and LMB-2 appears to be synergistic. Different from DSP30, the control ODNs pZ27 and C27 failed to modulate the toxicity of LMB-2 (Figure 2A). Sensitization of B-CLL cells to LMB-2 in the presence of DSP30 was first detectable after 72 hours, but maximal effects were observed after 96 to 120 hours (Figure 2B).

Inhibition of cell growth by LMB-2 in combination with ODN.

(A) B-CLL cells were grown in medium supplemented with 1 μg/mL LMB-2 and indicated concentrations of ODN. After 5 days, cell viability was assessed with an MTS assay: 10 μL of a combined MTS/PMS solution were added to the cell suspension. The adsorbance at 490 nm was assessed with an ELISA reader. Results are expressed as percent OD490, related to the OD490 of cells grown without immunotoxin. Results represent mean plus or minus SEM of independent experiments with cells from 3 different patients. (B) Inhibition of cell growth was measured in a B-CLL sample at different time points in the presence of 1 μg/mL LMB-2 with or without DSP30. An independent experiment gave comparable results.

Inhibition of cell growth by LMB-2 in combination with ODN.

(A) B-CLL cells were grown in medium supplemented with 1 μg/mL LMB-2 and indicated concentrations of ODN. After 5 days, cell viability was assessed with an MTS assay: 10 μL of a combined MTS/PMS solution were added to the cell suspension. The adsorbance at 490 nm was assessed with an ELISA reader. Results are expressed as percent OD490, related to the OD490 of cells grown without immunotoxin. Results represent mean plus or minus SEM of independent experiments with cells from 3 different patients. (B) Inhibition of cell growth was measured in a B-CLL sample at different time points in the presence of 1 μg/mL LMB-2 with or without DSP30. An independent experiment gave comparable results.

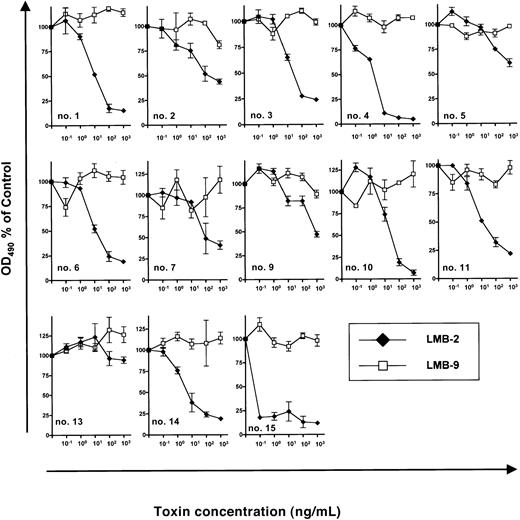

Next, we investigated inhibition of B-CLL growth by DSP30 and LMB-2 in a series of 13 patients. (Samples from patient no. 8 and patient no. 12 had to be excluded because DSP30 was cytotoxic to these cells.) In the presence of DSP30 at 1 μM, B-CLL cells from 12 patients were growth inhibited by LMB-2 after a 5-day incubation. OD490 was reduced from 0.37 ± 0.06 to 0.13 ± 0.05 in 13 samples after incubation with DSP30 and LMB-2 at 1 μg/mL. The concentrations, at which LMB-2 inhibited cell growth by 50% (IC50), were below 1 μg/mL (Figure3). Moreover, in 9 of 13 samples, the IC50 was 100 ng/mL or below.

Sensitivity of B-CLL cells from individual patients to immunotoxins in the presence of DSP30.

3 × 105 B-CLL cells were cultured in 100 μL medium containing DSP30 at 1 μM and indicated concentrations of LMB-2 or LMB-9. After 5 days, an MTS assay was performed as described in the text and in the legend to Figure 2. Results represent means of triplicates plus or minus SEM.

Sensitivity of B-CLL cells from individual patients to immunotoxins in the presence of DSP30.

3 × 105 B-CLL cells were cultured in 100 μL medium containing DSP30 at 1 μM and indicated concentrations of LMB-2 or LMB-9. After 5 days, an MTS assay was performed as described in the text and in the legend to Figure 2. Results represent means of triplicates plus or minus SEM.

B-CLL cells from patient no. 13 did not respond to LMB-2 in combination with DSP30, as the ODN failed to up-regulate CD25 expression in this leukemia (Figure 1C).

Although increased cytotoxicity of LMB-2 was only observed in samples in which CD25 was up-regulated, the amounts of CD25 expression as assessed by flow cytometry were not significantly correlated with the respective IC50 values. For instance, B-CLL cells from patient no. 15 were sensitized most efficiently (Figure 3) although CD25 expression levels were higher in other samples (eg, in patient no. 10 and patient no. 11) (Figure 1B).

As a specificity control, B-CLL cells from each patient were incubated with DSP30 in combination with LMB-9, an immunotoxin targeting a LewisY carbohydrate antigen, which is present on adenocarcinoma cells but not on hematopoietic tissues.40 42 No activity of LMB-9 was observed in any sample (Figure 3).

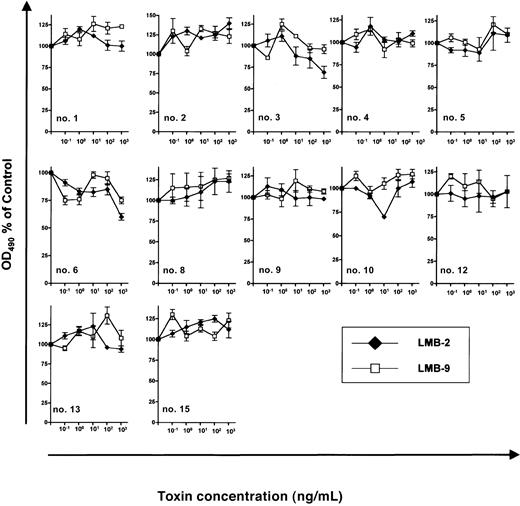

The antileukemic efficacy of LMB-2 was detectable only in cells treated with DSP30. In contrast, if B-CLL cells were incubated under otherwise identical conditions with LMB-2 in the absence of DSP30, no antileukemic activity was detectable (Figure4) with an OD490 remaining unchanged (0.27 ± 0.03 versus 0.28 ± 0.03). Twelve B-CLL samples were evaluable for this analysis since cells from patients no. 7, no. 11, and no. 14 died spontaneously in tissue culture unless the ODN was added.

Sensitivity of B-CLL cells from individual patients to immunotoxins.

3 × 105 B-CLL cells were grown for 5 days in 100 μL medium supplemented with indicated concentrations of LMB-2 or LMB-9. No ODN was added. Then, an MTS assay was performed as described in the text. Results represent means of triplicates plus or minus SEM.

Sensitivity of B-CLL cells from individual patients to immunotoxins.

3 × 105 B-CLL cells were grown for 5 days in 100 μL medium supplemented with indicated concentrations of LMB-2 or LMB-9. No ODN was added. Then, an MTS assay was performed as described in the text. Results represent means of triplicates plus or minus SEM.

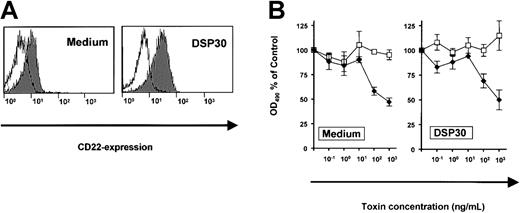

The effects of DSP30 were related to increased expression of the target antigen, CD25. To exclude the possibility of a nonspecific interaction of DSP30 with a toxin, we performed a control experiment with an immunotoxin to a different surface antigen on B-CLL cells. CD22, the target of the immunotoxin BL22, was only slightly up-regulated upon treatment of B-CLL cells with DSP30 (Figure5A). Dose-response experiments revealed similar sensitivities to BL22 in the presence or in the absence of DSP30 (Figure 5B). In conclusion, the CpG-ODN sensitizes B-CLL cells to the cytotoxicity of immunotoxin LMB-2 specifically by up-regulation of the respective target antigen on the cell surface.

Expression of CD22 and cytotoxicity of immunotoxin BL22 in B-CLL cells.

(A) B-CLL cells were cultured for 48 hours with DSP30 or without ODN. They were then stained with a fluorochrome-labeled monoclonal antibody to CD22 or with a labeled isotype control antibody. Cellular fluorescence was assessed by flow cytometry. (B) B-CLL cells were incubated with DSP30 and indicated concentrations of immunotoxin BL22. After 5 days in culture, cell viability was assessed with an MTS assay as described in the text. Results represent means plus or minus SEM from triplicates. Shown is a representative experiment; 2 additional experiments gave similar results. ♦ indicates LMB-2; ■, LMB-9.

Expression of CD22 and cytotoxicity of immunotoxin BL22 in B-CLL cells.

(A) B-CLL cells were cultured for 48 hours with DSP30 or without ODN. They were then stained with a fluorochrome-labeled monoclonal antibody to CD22 or with a labeled isotype control antibody. Cellular fluorescence was assessed by flow cytometry. (B) B-CLL cells were incubated with DSP30 and indicated concentrations of immunotoxin BL22. After 5 days in culture, cell viability was assessed with an MTS assay as described in the text. Results represent means plus or minus SEM from triplicates. Shown is a representative experiment; 2 additional experiments gave similar results. ♦ indicates LMB-2; ■, LMB-9.

Toxicity of LMB-2 to normal lymphocytes

Sensitization of B-CLL cells to an immunotoxin could be a potentially harmful treatment approach if the toxicity toward normal lymphocytes were increased accordingly. We therefore analyzed the effects of DSP30 and LMB-2 in normal T lymphocytes from peripheral blood, and B cells from tonsils of patients undergoing tonsillectomy for nonmalignant disease. Figure 6A shows that incubation with DSP30 increased CD25 expression in purified normal B lymphocytes only moderately compared with B-CLL cells. No increase was observed in normal T cells (Figure 6B). These results were confirmed with experiments in which unseparated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from patients with B-CLL were analyzed. These samples contained T cells (Figure 6C). CD25 was up-regulated by the ODN only in CD19+ B cells, but not in CD3+ T lymphocytes.

Modulation of CD25 expression in normal lymphocytes by DSP30.

B-lymphocytes from tonsils of patients with nonmalignant diseases (A), or normal T cells from peripheral blood (B) were isolated by density gradient centrifugation and immunomagnetic enrichment as described in the text. Cells were incubated with DSP30 for 48 hours, followed by staining with fluorochrome-labeled, monoclonal anti-CD25 antibodies or isotype control antibodies. Cellular fluorescence was analyzed by flow cytometry. Histograms show fluorescence intensities of the anti-CD25 antibody (shaded), overlayed with that of an isotype control (solid line). Shown are representative experiments; 2 additional experiments gave similar results. (C) Unseparated peripheral blood cells from a patient with B-CLL were incubated for 48 hours in the presence or in the absence of DSP30. Cells were then stained for flow cytometric analysis with FITC-conjugated anti-CD25 antibodies and PE-labeled antibodies to CD3 or CD19.

Modulation of CD25 expression in normal lymphocytes by DSP30.

B-lymphocytes from tonsils of patients with nonmalignant diseases (A), or normal T cells from peripheral blood (B) were isolated by density gradient centrifugation and immunomagnetic enrichment as described in the text. Cells were incubated with DSP30 for 48 hours, followed by staining with fluorochrome-labeled, monoclonal anti-CD25 antibodies or isotype control antibodies. Cellular fluorescence was analyzed by flow cytometry. Histograms show fluorescence intensities of the anti-CD25 antibody (shaded), overlayed with that of an isotype control (solid line). Shown are representative experiments; 2 additional experiments gave similar results. (C) Unseparated peripheral blood cells from a patient with B-CLL were incubated for 48 hours in the presence or in the absence of DSP30. Cells were then stained for flow cytometric analysis with FITC-conjugated anti-CD25 antibodies and PE-labeled antibodies to CD3 or CD19.

In unstimulated B and T lymphocytes, no specific cytotoxicity of LMB-2 was detected above the level of LMB-9 toxicity (Figure7). Furthermore, LMB-2 was relatively untoxic to DSP30-treated normal lymphocytes of both lineages (Figure7). In summary, both up-regulation of CD25 expression and sensitization to the toxicity of LMB-2 are more pronounced in B-CLL cells than in normal lymphocytes.

Effect of DSP30 on sensitivity to LMB-2 of normal lymphocytes.

Human tonsillar B cells (A) and T cells from peripheral blood of healthy donors (B) were isolated as described in the text and in the legend to Figure 6. 3 × 105 T lymphocytes and tonsillar B cells were cultured with or without DSP30 in the presence of indicated concentrations of LMB-2 (♦) or LMB-9 (■). Cell viability was determined with an MTS assay after 5 days as described in the text. Human tonsillar B cells cultured in medium alone were measured after 3 days. Shown are representative experiments; 2 additional experiments gave similar results.

Effect of DSP30 on sensitivity to LMB-2 of normal lymphocytes.

Human tonsillar B cells (A) and T cells from peripheral blood of healthy donors (B) were isolated as described in the text and in the legend to Figure 6. 3 × 105 T lymphocytes and tonsillar B cells were cultured with or without DSP30 in the presence of indicated concentrations of LMB-2 (♦) or LMB-9 (■). Cell viability was determined with an MTS assay after 5 days as described in the text. Human tonsillar B cells cultured in medium alone were measured after 3 days. Shown are representative experiments; 2 additional experiments gave similar results.

Discussion

We have shown that B-CLL cells resistant to a recombinant immunotoxin targeting CD25 are efficiently sensitized upon treatment with immunostimulatory phosphorothioate ODN. To our knowledge, this is the first report that modulation of surface antigen expression on malignant cells by CpG-ODN leads to sensitization to an immunotoxin or an antibody. In our study, the immunotoxin LMB-2 exerted no cytotoxicity toward B-CLL cells unless CpG-ODNs were present. Addition of the CpG-ODN decreased the IC50 of LMB-2 to concentrations that are in the range of plasma levels in patients.10

Up-regulation of CD25 by CpG-ODN was observed in all but one of the B-CLL samples. Sensitization to the immunotoxin LMB-2 was specifically due to the up-regulation of the CD25 target because BL22, another immunotoxin whose target antigen was modulated to a much lesser extent, displayed similar cytotoxicity with or without CpG-ODN. In addition, the truncated Pseudomonas exotoxin domain was not involved in an interaction with the immunostimulatory ODN because the cells were not sensitized to immunotoxin LMB-9, which does not recognize B-CLL cells.

LMB-2 is very cytotoxic to various cells expressing CD25, with fewer than 1000 molecules per cell being sufficient for complete responses in an in vivo model.45 Thus, the presence of adequate numbers of binding sites is a prerequisite for the efficacy of an immunotoxin. Most HCL and T-cell leukemia cells express higher numbers of CD25 molecules than B-CLL cells.25 Nonetheless, it is not obvious that increased numbers of CD25 molecules after CpG-ODN treatment are sufficient for sensitization to LMB-2. B-CLL cells tend to be generally less sensitive to LMB-2 than HCL or T-cell leukemia cells even if comparable numbers of binding sites are present.25 It has been suggested that HCL cells are more efficient than B-CLL cells in internalizing and intracellularly transporting the immunotoxin.25 Multiple steps are required to ensure that the toxin is delivered in its active form to bind to elongation factor 2.16-22 Results presented here suggest that, following stimulation with CpG-ODN, the numbers of CD25 target molecules on the surface of B-CLL cells are high enough to overcome this limitation.

In our study, all B-CLL samples failed to respond to LMB-2 in the absence of ODN. In contrast, Kreitman and coworkers reported that a similar immunotoxin, anti-Tac(Fv)–PE40KDEL, inhibited protein synthesis in 50% of CLL samples.26 Besides differences among individual patients, several reasons may account for this discrepancy. First, the incubation periods were different, 60 to 62 hours versus 5 days. We used longer incubation periods to allow for up-regulation of the target structure. Moreover, the sensitivity of B-CLL cytotoxicity assays depends on cell densities. In a study by Robbins et al in which extremely high densities were used, better responses were observed compared with our study as well as a previous study by Kreitman and coworkers.25,26 Second, the MTS assay used in the present study determines cell viability, whereas Kreitman and coworkers analyzed protein synthesis by incorporation of radiolabeled leucine. Since inhibition of protein synthesis is the cellular mechanism interrupted by PE38, it is possible that assessment of cell viability by an MTS assay underestimates the toxicity of LMB-2 in comparison with the leucin incorporation assay. Third, the toxin containing a KDEL sequence is more toxic to B-CLL cells than LMB-2.25 Whereas the native carboxy-terminus of LMB-2 consists of the amino acids REDLK, the KDEL sequence binds to the intracellular KDEL receptor with higher affinity, resulting in more efficient transport to the endoplasmatic reticulum and higher cytotoxicity.19 46 LMB-2 has been introduced into the clinic because preclinical studies demonstrated lower systemic toxicity in primates than the respective, KDEL-containing toxin.

The mode by which LMB-2 exerts its cytotoxicity to B-CLL cells is not fully understood. Preliminary investigations have revealed that caspase-3–mediated apoptosis is involved in some, but not all patients (data not shown). This is in accord with observations in permanent cell lines. Whereas most cells die following induction of apoptosis, HUT-102 leukemic cells from a patient with mycosis fungoides are being killed without activation of caspases.22 The mechanism by which apoptosis-resistant CLL cells are killed requires further study.

In addition, the schedule of exposure to CpG-ODN and immunotoxin need not necessarily be optimal. We have incubated B-CLL cells simultaneously with LMB-2 and CpG-ODN. This schedule was chosen for practical reasons. Because of the limited stability of LMB-2, it is conceivable that a sequential application where the toxin is added after prior stimulation of cells with CpG-ODN may be more efficient. Further studies should determine the time course of CD25 induction by CpG-ODN, and optimize the conditions for antileukemic treatment. This is pertinent before a combination therapy of LMB-2 and CpG-ODN can be introduced into the clinic.

CpG-ODNs have been evaluated in murine and primate animal models and are currently being studied in early clinical trials (reviewed in Weiner37). CpG-ODNs were generally well tolerated. However, repeated application of large doses can cause a wasting syndrome in rodents due to cytokine production and proliferation of natural killer (NK) cells and B lymphocytes.37,47 We have demonstrated that stimulation with DSP30 does not sensitize normal B cells and T cells to treatment with an immunotoxin (Figure 6, Figure 7), but further investigations (eg, in animal models) are needed before treatment with both substances can be started in clinical trials. The CpG motif is important for maximal stimulation of human B cells but phosphorothioate ODNs, which have been most stimulatory in mice, have demonstrated only weak activity in human immune cells.48,49 Other motifs such as TCG repeats (which are present at the 5′ end of DSP30) might be important as well.33,48 Although nonspecific effects of the phosphorothioate backbone have been described,50 a highly active phosphodiester CpG-ODN has been described recently.48 The effects observed in our study are not primarily due to the phosphorothioate backbone because no sensitization was observed in the presence of the phosphorothioate ODN C27.

Although stimulation of leukemic growth by CpG-ODN would be a major concern to clinical application of these compounds, the proliferative capacity of CpG-ODN–treated B-CLL cells was weaker than that of normal lymphocytes.38 In contrast, the CD25 up-regulation was much stronger in B-CLL cells than in normal peripheral blood B cells or tonsillar B cells (Figure 6 and Decker et al39). Therefore, normal B cells might fail to reach a threshold expression of CD25 for effective cell kill by the immunotoxin. Our current study confirms that sensitization to the immunotoxin outweighs the growth-stimulatory effects in B-CLL cells. Furthermore, the increased sensitivity of B-CLL cells compared with normal lymphocytes to a combination of CpG-ODN and the immunotoxin allows selective intervention.

The increased immunogenicity of B-CLL cells treated with CpG-ODN38,39 may result in additional antitumor effects. CpG-ODNs have been used as adjuvants in tumor immunization.34,35,51 In mice they induce rejection of neuroblastoma xenografts50 and inhibit the growth of B16 melanoma.37 The antitumor activity is most likely related to activation of NK cells,37,52,53 and induction of the production of cytokines with anticancer activity such as interleukin-12, tumor necrosis factor-α, and interferon-γ.53-55

Further studies should determine whether the immunostimulatory effect of CpG-ODN is maintained upon combination with the immunotoxin. Death of B-CLL cells after treatment with a combination of CpG-ODN and immunotoxin may even cause an increased immune response due to antigen presentation by apoptotic cells.

It has been shown in an animal model that CpG-ODNs increase the efficacy of monoclonal antibodies to murine 38C13 lymphomas.36 In that study, the cytolytic activity of NK cells was enhanced by CpG-ODNs. A single injection with CpG-ODN was as effective as multiple administrations of interleukin-2 in inducing antitumor immunity if combined with a monoclonal antibody. Thus, antibody-dependent cellular toxicity is thought to play a major role in the immunostimulatory activity of CpG-ODNs. Whether or not the phenotype of lymphoma cells was changed was not reported in this study.

Our investigation shows that the modulation of antigen expression on malignant cells by CpG-ODNs can significantly contribute to the antitumor activity of an immunotoxin. Up-regulation of target molecules for potential antibody therapy by CpG-ODN is not confined to B-CLL but has been recently reported in other non-Hodgkin lymphoma entities.56 Therefore, it appears possible that additional applications for this new treatment approach can be identified.

We wish to thank H. Wagner for helpful discussions and Maria Gallo for critically reading the manuscript.

Supported by a research grant from the Technical University of Munich, Germany, (KKF H30-97), and by a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (De 771/1-1).

One of the authors (I.P.) has declared a financial interest in a company whose product was studied in the present work.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Thomas Decker, 3rd Department of Medicine, Technical University of Munich, Ismaninger Str 15, 81675 Munich, Germany; e-mail: t.decker@lrz.tum.de.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal