Abstract

Approximately 20% of childhood B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) has a TEL-AML1 fusion gene, often in association with deletions of the nonrearranged TEL allele.TEL-AML1 gene fusion appears to be an initiating event and usually occurs before birth, in utero. This subgroup of ALL generally presents with low- or medium-risk features and overall has a very good prognosis. Some patients, however, do have relapses late or after the cessation of treatment, at least on some therapeutic protocols. They usually achieve sustained second remissions. Posttreatment relapses, or even very late relapses (5-20 years after diagnosis), in childhood ALL are clonally related to the leukemic cells at diagnosis (by IGH or T-cell receptor [TCR] gene sequencing) and are considered, therefore, to represent a slow re-emergence or escape of the initial clone seen at diagnosis. Microsatellite markers and fluorescence in situ hybridization identified deletions of the unrearranged TEL allele and IGH/TCR gene rearrangements were analyzed; the results show that posttreatment relapse cells in 2 patients with TEL-AML1–positive ALL were not derived from the dominant clone present at diagnosis but were from a sibling clone. In contrast, a patient who had a relapse while on treatment with TEL-AML1 fusion had essentially the sameTEL deletion, though with evidence for microsatellite instability 5′ of TEL gene deletion at diagnosis, leading to extended 5′ deletion at relapse. It is speculated that, in some patients, combination chemotherapy for childhood ALL may fail to eliminate a fetal preleukemic clone with TEL-AML1 and that a second, independent transformation event within this clone after treatment gives rise to a new leukemia masquerading as relapse.

Introduction

Childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is a biologically heterogeneous cancer, and much of the variation in clinical outcome can be related to clinical, hematologic, immunological, or molecular genetic features identified at diagnosis.1 Some molecular cytogenetic subgroups, withBCR-ABL or MLL fusion genes, for example, tend to present with high leukemic burdens and to have poor prognoses. Common subsets with either hyperdiploidy or TEL-AML1 gene fusions usually present with low-risk clinical and hematologic features and, overall, have favorable long-term remission and survival rates.2-5

However, the prognostic significance of a TEL-AML1 fusion gene has been subject to some controversy. This has primarily related to the observation that patients with this molecular marker have a uniformly impressive sustained remission rate on treatment but a variable relapse rate that develops “late,” after the cessation of treatment, and that is perhaps dependent on the particular therapeutic protocol used.5-13 At one extreme, in the Berlin-Frankfurt-Münster (BFM) clinical trials, 20% to 24% of patients with relapsed ALL had a TEL-AML1 fusion gene with a frequency similar to that observed at initial diagnosis.7,9 In contrast, in a series of patients treated on the (DFCI)-ALL Consortium protocol between 1980 and 1991, 0 of 22 patients with a TEL-AML1 fusion gene had a relapse.6

Relapses of TEL-AML1 fusion gene-positive ALL usually occur within 2 years of the cessation of treatment but may occur many years later.14 Marked features of these late relapses are that they are usually as clinically responsive as the leukemia at initial diagnosis and that they usually entail prolonged second remissions and possible cure. This differs from the clinical intransigence (or brief second remissions) of most early relapses of ALL during treatment and is contrary to what is generally anticipated in cancer regarding drug responsiveness of the disease at relapse.

Immunoglobulin or T-cell receptor (TCR-γ, TCR-δ) gene sequencing studies indicate that the leukemic cells in off-treatment relapses15 and in late relapse (5-20 years after diagnosis) in ALL16-19 are usually clonally related to those present at diagnosis, and at least some of these late relapses are now known to have a TEL-AML1 fusion gene.14In most cases, therefore, late relapse is not an independent or a secondary leukemia induced by therapy. The simplest interpretation of late relapse is that it represents the re-emergence, or escape from control or dormancy, of progeny derived from the dominant clone observed at diagnosis that survived therapeutic kill. We have considered an alternative interpretation based on recent insights into the molecular genetics and natural history of childhood ALL withTEL-AML1 fusion genes.20

Most often B-cell precursor or common (c) ALL in childhood with aTEL-AML1 fusion gene originates before birth, in utero.21TEL-AML1 gene fusion itself is probably the clonal initiating event. Twin studies22,23further suggest that this genetic recombination event is, in most cases, insufficient to generate overt ALL and that some additional secondary postnatal event is required. This has suggested a scenario in which TEL-AML1 generates a putative preleukemic clone that can persist in a clinically covert fashion for many years.20,23 At least one other complementary genetic event is then required for ALL, and this frequently includes deletion of the unrearranged TEL allele.24 Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) studies have suggested that the TELdeletion is secondary or subclonal to TEL-AML1fusion.25 Some, albeit incomplete, epidemiological data support the view that this critical secondary hit may be promoted by proliferative stress to the lymphoid progenitor compartment after infection.26

These observations suggested to us a novel potential explanation for late relapse of cALL with TEL-AML1 fusion genes—that combination chemotherapy usually eliminates the overt leukemic subclone that dominates at initial diagnosis but may (depending on protocol) fail to eradicate the underlying “preleukemic” clone. The latter persists after the cessation of therapy but then is subject to proliferative stress during the regenerative rebound or later during episodes of infection. Under these circumstances, there is an opportunity for a new genetic alteration to arise, and this may then convert a preleukemic cell to a new, overt leukemic clone. If this interpretation is correct, a simple prediction can be made with respect to the genetic events observed in late relapse of ALL. This is that the clones seen at diagnosis and relapse will differwith respect to secondary TEL deletions. If, for example, the normal TEL gene is deleted at diagnosis but present at relapse, or if it appears to be different (smaller or with different genomic boundaries) at relapse, then clearly the relapse cells cannot be derived from the leukemic cells dominant at the initial diagnosis. We show that this appears to be the case with leukemic cells from 2 patients in off-treatment relapse versus cells from a third patient who had a relapse while on treatment.

Patients, materials, and methods

Patients

Clinical features of the patients involved in this study are summarized in Table 1. They were selected on the basis of TEL-AML1 positivity at diagnosis and relapse and on the availability of frozen cell samples from diagnosis, complete remission, and relapse. All patients were treated according to the ALL-BFM 90 protocol for medium risk (including prophylactic central nervous system irradiation with 12 Gy).27 Remission was achieved after induction treatment. All relapses were treated according to the ALL-BFM 95 relapse protocol.

Clinical features of patients

| Patient . | Age at diagnosis . | Sex . | Blasts in bone marrow (%) . | Length of first remission . | Outcome . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 y 11 mo | F | D 96 | 32 mo | CCR (2nd) 90 mo* |

| R 90 | |||||

| 2 | 2 y 6 mo | M | D 98 | 42 mo | CCR (2nd) 56 mo |

| R 59 | |||||

| 3 | 2 y 7 mo | M | D 88 | 21 mo | 28 mo† |

| R 88 |

| Patient . | Age at diagnosis . | Sex . | Blasts in bone marrow (%) . | Length of first remission . | Outcome . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 y 11 mo | F | D 96 | 32 mo | CCR (2nd) 90 mo* |

| R 90 | |||||

| 2 | 2 y 6 mo | M | D 98 | 42 mo | CCR (2nd) 56 mo |

| R 59 | |||||

| 3 | 2 y 7 mo | M | D 88 | 21 mo | 28 mo† |

| R 88 |

After first relapse, received bone marrow transplant from sibling.

Died of multiorgan failure in second remission.

Molecular cytogenetics

Dual-color FISH was performed according to standard methods on methanol–acetic acid-fixed preparations of bone marrow cells that had been cultured for 24 hours. We used 2 cosmids (50F4 and cos664) specific for the TEL and the AML1 locus, respectively, and screened 200 nuclei per sample and also a few metaphases. The TEL probe covers 35 kb of intron 1 and exon 2.28 29

Microsatellite mapping of TEL deletions

Microsatellite mapping was performed essentially as described by Baccichet and Sinnett30 using some additional established markers located on 12p. Primer pair sequences for markers D12S352, D12S94, D12S356, D12 S336, D12S77, D12S89, D12S98, D12S320, D12S269, D12S70, D12S310, D12S363, and D12S87 were obtained from The Human Genome Database, and the primer DNA was obtained from OSWEL (University of Southampton, United Kingdom). DNA (7.5 ng) was subjected to polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and electrophoresis exactly as described.30 Loss of heterozygosity (LOH) was positive if the relative intensity of one allele for an informative marker heterozygous at remission was lost or diminished in the same patient, either at presentation or relapse.

Amplification and sequencing of clonal immunoglobulin and T-cell receptor gene rearrangements

Genomic DNA from initial diagnosis and relapse were screened for IGH (GL, incomplete DJ, and complete VDJ rearrangements), IGK-KDE, incomplete TCRD (D2-D3, V2-D3), and TCRG rearrangements using single or multiplex PCR as described previously.31,32 PCR reactions for the detection of germ-line configuration for TCRD genes were performed using intron sequences flanking the TCRD D3 segment. Clonality of PCR products was confirmed by direct sequencing. Identification of the involved gene segments was performed by searching for homology with all known human germ-line sequences obtained from the VBASE directory of human genes51 and by comparing them to the most recent update of GenBank using the BLAST sequence similarity searching tool.52 (We could not differentiate between TCRG J1.3 and J2.3 segments because a consensus primer was used for amplification, and sequencing was too short for differentiation). All PCR reactions were performed on at least 2 different occasions.

Results

All 3 patients had medium-risk ALL at diagnosis, as described in Schrappe et al.27 Two patients (pt1 and pt2) hadTEL-AML1–positive blasts (by FISH) at both diagnosis and relapse; relapse off treatment is defined here as late. A third patient (pt3) with TEL-AML1 fusion had a relapse while on treatment (Table 1).

Immunoglobulin and T-cell receptor gene rearrangements

Data are summarized in Table 2. In cells of patient 1, one clone-specific IGK rearrangement was detectable at diagnosis and in late relapse, confirming that the 2 are clonally related. An incomplete TCRD rearrangement (V2-D3) present at diagnosis was absent at relapse. This rearrangement could have undergone further rearrangements to Jα, resulting in a loss of this marker at relapse.33 Alternatively, the subclone at relapse might be distinct from that at diagnosis with respect to TCRD rearrangements. To differentiate between these 2 possibilities, germ-line PCR was run. At diagnosis no germ-line band was visible, indicating that the secondTCRD gene was most likely a V2-D3-Jα. In contrast, a germ-line band, but no rearrangement, was detectable at relapse, suggesting that the clone at relapse could not have evolved from the first (dominant) clone (either 2 genes in germ-line configurations or one in germ line and the other rearranged; V2-D3-Jα).

Antigen receptor gene status at initial diagnosis and relapse

| Patient . | Antigen receptor genes . | Configuration at initial diagnosis . | Configuration at relapse . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | IGH | GL | V3/D3/J1 |

| IGK | RSS-KDE | RSS-KDE | |

| TCRD | V2-D3, no GL | GL | |

| 2 | IGH | V3/D3/J6 | |

| V1/D4/J6 | V1/D4/J6 | ||

| TCRG | V1-J1.3/2.3 | ||

| V2-J1.3/2.3, no GL | V2-J1.3/2.3 | ||

| 3 | TCRD | V2-D3 | V2-D3 |

| TCRG | V1-J1.3/2.3 | V1-J1.3/2.3 |

| Patient . | Antigen receptor genes . | Configuration at initial diagnosis . | Configuration at relapse . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | IGH | GL | V3/D3/J1 |

| IGK | RSS-KDE | RSS-KDE | |

| TCRD | V2-D3, no GL | GL | |

| 2 | IGH | V3/D3/J6 | |

| V1/D4/J6 | V1/D4/J6 | ||

| TCRG | V1-J1.3/2.3 | ||

| V2-J1.3/2.3, no GL | V2-J1.3/2.3 | ||

| 3 | TCRD | V2-D3 | V2-D3 |

| TCRG | V1-J1.3/2.3 | V1-J1.3/2.3 |

Underlining indicates identical rearrangements at initial diagnosis and relapse; GL, germ line.

The IGH genes in the leukemic cells of patient 1 were in germ-line configuration at diagnosis (no incomplete or completeIGH rearrangement in the presence of a germ-line band), whereas at relapse one complete IGH rearrangement, in addition to a germ-line band, was found. No other (complete or incomplete) IGH rearrangement was detectable. The new rearrangement at relapse might have developed from either a germ-line configuration of the initial clone or from a subclone (comprising less than 0.1%-1%—the sensitivity limit of PCR—of the initial leukemia).

In patient 2, diagnostic and late relapse leukemic cells shared one identical IGH gene rearrangement and one identical TCRG rearrangement (Table 2), confirming that they were clonally related or were derived from a common precursor with a stable rearrangement of these 2 alleles. At diagnosis, cells of patient 2 had a second allelic rearrangement of IGH—VH3(DP50)/D3-3/J6—that was absent from the relapse cells and a second TCRG rearrangement—V1-J1.3/2.3—that was also absent from the relapse cells.

In patient 3, who had a relapse while on treatment, there was noIGH or IGK rearrangement at either initial diagnosis or relapse. However, diagnostic and relapse leukemic cells shared identical TCRD and TCRG rearrangements (Table 2).

TEL deletions

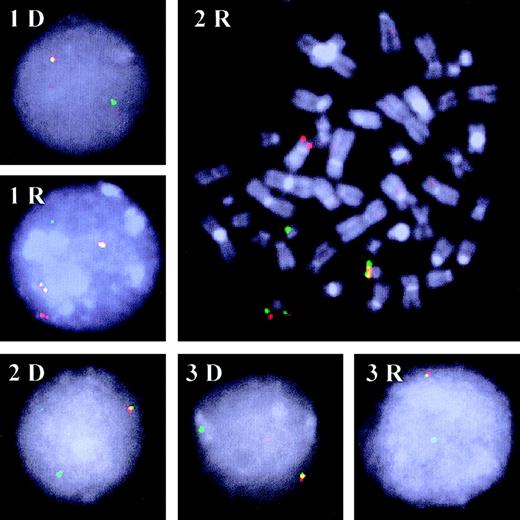

Patients 1 and 2 each had a deletion of the normal TELallele at diagnosis, as revealed by FISH (Figure1; Table3), but at relapse all individual leukemic cells with a TEL-AML1 fusion gene appeared to retain a normal TEL allele (Figure 1; Table 3). Banded karyotype analysis of leukemic metaphases at diagnosis and relapses of patients 1 and 2 revealed differences (in addition to changes inTEL deletion status and maintenance of TEL-AML1fusion). However, the failure to detect any abnormal karyotypes in patient 1 in relapse or in patient 2 at diagnosis could indicate that the small number of karyotypes examined were in nonleukemic cells. Patient 3 had leukemic cells at both diagnosis and relapse with a deletion of normal TEL by FISH (Figure 1).

FISH patterns.

Representative FISH patterns of interphase and metaphase (2R) nuclei were obtained with the TEL (TRITC-labeled; red) andAML1 (FITC-labeled; green) probes in the 3 patients at diagnosis (D) and relapse (R). Most leukemic cells studied at diagnosis of all 3 patients (1D, 2D, and 3D) and at relapse for patient 3 (3R) had a TEL-AML colocalization (yellowish signal) and, as indicated by the missing red signal, a deletion of the secondTEL allele. A different pattern was observed in the relapse samples of patients 1 and 2 (1R and 2R). The signal for the secondTEL allele was clearly present. In addition, 2TEL-AML colocalizations indicated the duplication of the der21 that harbors the relevant gene fusion.

FISH patterns.

Representative FISH patterns of interphase and metaphase (2R) nuclei were obtained with the TEL (TRITC-labeled; red) andAML1 (FITC-labeled; green) probes in the 3 patients at diagnosis (D) and relapse (R). Most leukemic cells studied at diagnosis of all 3 patients (1D, 2D, and 3D) and at relapse for patient 3 (3R) had a TEL-AML colocalization (yellowish signal) and, as indicated by the missing red signal, a deletion of the secondTEL allele. A different pattern was observed in the relapse samples of patients 1 and 2 (1R and 2R). The signal for the secondTEL allele was clearly present. In addition, 2TEL-AML colocalizations indicated the duplication of the der21 that harbors the relevant gene fusion.

Molecular cytogenetics of leukemic cells at diagnosis versus relapse

| Patient . | Status . | TEL/AML FISH . | Cytogenetics . | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interphase (%) . | Metaphases . | |||||||||

| Negative . | Positive . | +21 . | TEL deletion . | +ider(21)3-150 . | Negative . | Positive . | +ider(21)3-150 . | |||

| 1 | Dgn | 38 | 62 | 0 | 60 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 44,XX,-X,-9,-12,+mar [4] 46,XX [9]3-151 |

| Rel | 29 | 71 | 0 | 0 | 48 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 46,XX [8] | |

| 2 | Dgn | 20 | 80 | 20 | 65 | 0 | 8 | 3 | 0 | 46,XY [1] |

| Rel | 9 | 91 | 0 | 0 | 85 | 1 | 7 | 7 | 47,XY,t(5;14)(q13;q33),+21 [17] 46,XY [3] | |

| 3 | Dgn | 60 | 40 | 0 | 32 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 46,XY,del(12)(p13) [20] |

| Rel | 34 | 66 | 0 | 66 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | |

| Patient . | Status . | TEL/AML FISH . | Cytogenetics . | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interphase (%) . | Metaphases . | |||||||||

| Negative . | Positive . | +21 . | TEL deletion . | +ider(21)3-150 . | Negative . | Positive . | +ider(21)3-150 . | |||

| 1 | Dgn | 38 | 62 | 0 | 60 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 44,XX,-X,-9,-12,+mar [4] 46,XX [9]3-151 |

| Rel | 29 | 71 | 0 | 0 | 48 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 46,XX [8] | |

| 2 | Dgn | 20 | 80 | 20 | 65 | 0 | 8 | 3 | 0 | 46,XY [1] |

| Rel | 9 | 91 | 0 | 0 | 85 | 1 | 7 | 7 | 47,XY,t(5;14)(q13;q33),+21 [17] 46,XY [3] | |

| 3 | Dgn | 60 | 40 | 0 | 32 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 46,XY,del(12)(p13) [20] |

| Rel | 34 | 66 | 0 | 66 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | |

FISH indicates fluorescence in situ hybridization; dgn, diagnosis; rel, relapse.

ider(21)(q10) t(12;21)(p13;q22).

Note that subsequent interphase FISH analyses indicated that most leukemic cells retained both copies of chromosome 12 but had lost one copy of X and 9 (see “Results”).

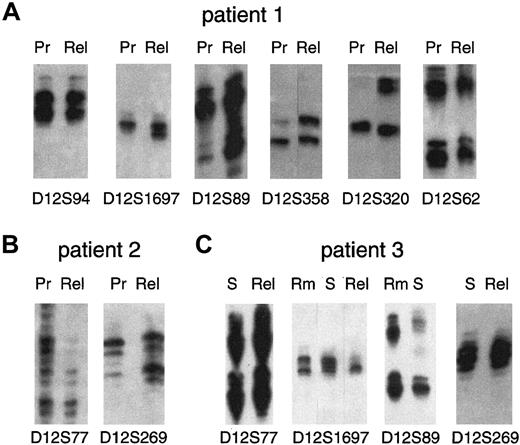

Because LOH can only be detected in patients heterozygous for a particular microsatellite marker, we next used highly polymorphic markers to compare the genomic boundaries of the 12p deletions seen by FISH at presentation versus those observed in relapse. Heterozygosity analysis was always performed on DNA isolated from patient cells in remission (data not shown). Figure 2A is a composite picture of informative markers for patient 1 centered around D12S94, D12S1697, D12S89, D12S358, D12S320, and D12S62, all of which were heterozygous. The most telomeric marker shown, D12S94, retains heterozygosity in presentation and relapse because the ratio of the upper and lower alleles is the same. In contrast, the marker D12S1697 shows LOH at presentation (seen by the loss of the lower allele) but is heterozygous in relapse. Markers for D12S89, D12S358, and D12S320 similarly show allelic loss at presentation but not in relapse. Because the marker D12S89 is positioned just upstream ofTEL exon 2, the probe used for FISH analysis, these results are in agreement with the FISH data and confirm a deletion of 12p in presentation but not in late relapse. A summary of the microsatellite mapping data over chromosome 12p and the relevant FISH data are shown in Figure 3 (pt 1). Informative data for patient 2 is presented in Figure 2B and shows the marker D12S77 to be present at diagnosis but allelic loss at relapse. Conversely, the marker D12S269 shows LOH in presentation and retained at relapse. As shown in the summary data (Figure 3 [pt 2]), leukemic cells from patient 2 had allelic loss of at least 11 cM DNA that encompassed markers D12S1697, through TEL, to beyond D12S269. Other markers in this region were noninformative and precluded a finer dissection of the deletion. In contrast, patient 2 cells in relapse are seen to harbor a different, smaller deletion that begins telomeric to the first at D12S77, includes D12S1697 (just upstream of TELexon 1A), but does not extend as far downstream as D12S269. In addition, this deletion was not detected by the probe used for FISH, suggesting that the deletion in relapse does not extend much further into the TEL allele than exon 1. This result again shows a marked difference from the deletion seen at presentation and is one that cannot readily be explained by an accumulative deletion that occurred during treatment.

Detection of LOH on chromosome 12p by microsatellite marker mapping.

Allotypes at informative (heterozygous) markers are shown for each patient at presentation (Pr) and relapse (Rel). (A) Patient 1 (late relapse) retains heterozygosity at markers D12S94 and D12S62 but shows LOH (markers D12S1697, D12S89, D12S358, and D12S320) at presentation but not at relapse. (B) Patient 2 (late relapse) shows LOH of marker D12S77 at relapse but not at presentation and LOH of marker D12S269 at presentation but not at relapse. (C) Patient 3 (early relapse) cells at presentation were FACS sorted (S) and show heterozygosity at markers D12S77 and D12S269, as does relapse DNA. Sorted cells at presentation show microsatellite instability in D12S1697 with the appearance of an extra band not present in remission (Rm) and further show LOH at relapse. Marker D12S89 is heterozygous in remission but shows LOH at presentation (S).

Detection of LOH on chromosome 12p by microsatellite marker mapping.

Allotypes at informative (heterozygous) markers are shown for each patient at presentation (Pr) and relapse (Rel). (A) Patient 1 (late relapse) retains heterozygosity at markers D12S94 and D12S62 but shows LOH (markers D12S1697, D12S89, D12S358, and D12S320) at presentation but not at relapse. (B) Patient 2 (late relapse) shows LOH of marker D12S77 at relapse but not at presentation and LOH of marker D12S269 at presentation but not at relapse. (C) Patient 3 (early relapse) cells at presentation were FACS sorted (S) and show heterozygosity at markers D12S77 and D12S269, as does relapse DNA. Sorted cells at presentation show microsatellite instability in D12S1697 with the appearance of an extra band not present in remission (Rm) and further show LOH at relapse. Marker D12S89 is heterozygous in remission but shows LOH at presentation (S).

Chromosome 12p deletions in presentation and relapse.

Schematic representation of chromosome 12p showing the position of microsatellite markers and boundaries of deletion (LOH; ○) in presentation or relapse compared to remission samples. ● indicates present;  , not informative. SCDR is the shortest commonly deleted region.50 The microsatellite instability in patient 3 (⊙) is marked with a star.

, not informative. SCDR is the shortest commonly deleted region.50 The microsatellite instability in patient 3 (⊙) is marked with a star.

Chromosome 12p deletions in presentation and relapse.

Schematic representation of chromosome 12p showing the position of microsatellite markers and boundaries of deletion (LOH; ○) in presentation or relapse compared to remission samples. ● indicates present;  , not informative. SCDR is the shortest commonly deleted region.50 The microsatellite instability in patient 3 (⊙) is marked with a star.

, not informative. SCDR is the shortest commonly deleted region.50 The microsatellite instability in patient 3 (⊙) is marked with a star.

Because of the low percentage of blast cells with theTEL-AML1 fusion in patient 3, it was not possible to obtain an accurate picture of 12p deletions at presentation given the high background of normal cells. We therefore used flow cytometry to sort CD10+/CD19+ low side-scatter cells to achieve an almost pure (approximately 95%) population of t(12;21) leukemic cells. As seen in Figure 2C, the heterozygous marker D12S77 is retained in the sorted cells at presentation and at relapse. At presentation, the marker D12S1697 shows microsatellite instability as depicted by the extra band compared to the remission pattern and shows complete allelic loss of this marker at relapse. The marker D12S89 shows LOH in presentation and relapse samples, and the next informative marker D12S269 is present (heterozygous) in both. All other informative markers were present (Figure 3 [pt 3]).

Other molecular cytogenetic differences

Metaphase cells at diagnosis versus relapse of patient 1 indicated that further molecular cytogenetic differences existed between these clones. To consolidate these data, we performed further interphase FISH analyses with centromeric-specific DNA probes for chromosomes 7, X (dual color with probes D721 and DXZ1), and 12 (D12Z1) and with a heterochromatin-specific probe for chromosome 9 (D921). Screening of 100 nuclei at diagnosis revealed 73% with −X and 81% with −9, but 95% with 2 copies of chromosome 12. In contrast, at relapse 99%, 95%, and 98% had 2 signals for chromosome X, 9, and 12, respectively. These analyses reveal further diversity of the clone present at diagnosis and discrepancies that can occur between cytogenetic and FISH-based scrutiny of chromosomes. Thus, by karyotypic analysis, 4 of 4 leukemic metaphases had −12 (Table 3), but by FISH analysis (of interphase cells), only 5% had loss of chromosome 12. Microsatellite analyses were also compatible with the retention of chromosome 12 by most cells (ie, no loss of heterozygosity) at loci either side of theTEL deletion (Figure 3 [pt 1]).

Discussion

A significant rate of posttreatment relapse of “low-risk” childhood ALL is reported in some7,9,11,34 but not all8 clinical studies of ALL with TEL-AML1fusion genes. A small fraction (−2%) of low-risk childhood ALL have late relapse—5 to 24 years after initial diagnosis. This fraction may include patients with TEL-AML1.14 These observations raise important concerns about the biologic nature of continuous remission, cure, or late relapse and have implications for treatment, management, and counseling.

Relapse or reoccurrence can have more than one biologic explanation, including the appearance of another, unrelated leukemia induced by genotoxic therapy. Most secondary leukemias are, however, myeloid. The usual explanation for relapse of childhood ALL is that it represents re-emergence of the original disease.35 Off-treatment or late relapse of childhood ALL is intraclonal, as judged byIGH or TCR sequence analysis.16-19 However, this begs the question why patients with TEL-AML1 have relapses after the cessation of maintenance therapy and why they usually have very good responses to therapy and high probability of sustained second remission or “cure.” Failure of prior immune surveillance36 or microenvironmental restraint37 of residual disease are possible answers. Our data suggest another.

Our analysis of unrearranged TEL gene status in 2 patients with off-treatment relapse of TEL-AML1–positive ALL, along with IGH/TCR clonal rearrangement status and FISH molecular cytogenetic data, provides clear evidence that leukemic cells in relapse could not have been derived from the dominant clone present at diagnosis, despite being clonally related as indicated byIGH/TCR gene analysis. Either the TEL allele deleted at diagnosis was absent at relapse (patient 1) or a different, smaller TEL deletion was present at relapse (patient 2). Although we have only been able to evaluate 2 patients with late-relapse ALL, other patients with TEL-AML1 at both diagnosis and late relapse are reported to be discordant forTEL deletions (C. Harrison, personal communication, 2000). These data are in accord with the hypothesis we proposed in pursuing these experiments, which is that late relapse of ALL might, in at least some patients, represent a transformation of cells belonging to a persistent preleukemic clone that survived induction and maintenance chemotherapy. We speculate that these persistent or quiescent cells may represent the original preleukemic clone generated byTEL-AML1 fusion in utero, though clearly we have no direct evidence that these cells are preleukemic rather than leukemic. We have not demonstrated that relapse and diagnostic blasts do share, as we assume, the same clonotypic TEL-AML1 genomic fusion sequence. This was the case for patient 3 (data not shown), but in the 2 patients with off-treatment relapse (patients 1 and 2), we were unable to amplify the genomic sequence of TEL-AML1 by long-distance PCR methods that usually, but not invariably, provideTEL-AML1 amplicons.38

In patient 3, who had a relapse of TEL-AML1–positive ALL while on treatment, the picture appears to be different. Through FISH we observed a deletion of normal TEL at diagnosis and relapse. However, the paired samples were not identical at theTEL locus. At diagnosis, there was evidence of microsatellite instability telomeric (5′) to theTEL deletion, and in the relapse leukemic cells this region was deleted. Although we cannot be certain of the molecular and clonal sequence of events here, the data are compatible with microsatellite instability leading to further deletion within the same subclone. Recently, the accumulation of microsatellite instability in childhood ALL has been reported, especially localized to chromosome 12p, implicating a fragile region close to TEL with an increased rate of genetic alteration.39 40

Our preferred interpretation of off-treatment relapse accords with the prior observation that putative preleukemic clones generated prenatally by TEL-AML1 fusion23 or other molecular events41 can persist in a clinically covert or silent form for 10 years or more. The plausibility of this interpretation of late relapse of TEL-AML1–positive relapses in ALL rests on the premise that the preleukemic clone with TEL-AML1 fusion alone is intrinsically less sensitive to chemotherapy than the overtly leukemic cells at diagnosis. There is no evidence to date that bears on this assumption, but theoretical possibilities include slower cell cycle dynamics or dormancy. The idea that preleukemic clones persist in treated patients in remission has been suggested before in the context of AML and by evidence provided from G6PD42 or PGK43 clonality assays and detection ofAML1-ETO fusion genes in “nonleukemic” stem cells.44

The likely cause of any secondary transformation event as postulated here is unknown. The model of the natural history of childhood B-cell precursor ALL that prompted these studies suggests that proliferative stress to a delayed but common infection promotes ALL development through mutation (or TEL deletion) in a preleukemia clone that usually arises by gene fusion in utero.20 A second transformation in late relapse could also arise after infectious episodes or could be linked to the proliferative stress that occurs in the B-lymphoid progenitor compartment after the cessation of maintenance chemotherapy.45 46

An alternative explanation for these data that cannot be excluded is that the clone that dominates at relapse is derived from a minor subclone of overt leukemic cells already present at diagnosis—a subclone that acquired genetic changes in addition toTEL-AML1. The leukemic clone present at diagnosis in patients 1 and 2 was genetically diverse, as indicated by FISH and metaphase cytogenetics.

The proportion of patients with TEL-AML1–positive ALL who do have relapses late or after treatment is not entirely known, but it does seem to vary considerably depending on therapeutic protocols.TEL-AML1–positive leukemic cells have been shown to be differentially sensitive to L-asparaginase,47 and it may be significant, therefore, that USA-based clinical regimens associated with the lowest rates of late relapse (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute ALL Consortium and St Jude Children's Research Hospital protocols) include early consolidation therapy with intensive L-asparaginase.6,8 If our interpretation is correct, it follows that such treatment eliminates the overt ALL clone present at diagnosis and the underlying preleukemic (fetal) clone. It may be possible to assess this prediction by sensitive monitoring for clonotypic TEL-AML1 genomic sequences by PCR.21

Our data and interpretation carry implications for the management of childhood ALL. If a fetal preleukemic clone of cells is not eliminated by therapy, it might be detectable by sensitive PCR-based methods. In such cases, ALL might have been eradicated, but a small but significant chance of recurrence remains because of a second, independent transformation event. However, it appears that the probability of this occurring is reduced to a negligible level, with some therapeutic protocols that may destroy all cells bearingTEL-AML1 fusion genes irrespective of malignant status.

Given the few patients we have studied, our conclusions are necessarily speculative. Nevertheless, they provide a plausible explanation for puzzling clinical observations in childhood ALL and should encourage further molecular scrutiny of patients who are in sustained complete remission after the cessation of therapy or who relapse.

The “premalignant” interpretation we favor for at least some cases of relapse in ALL may be applicable to some other cancers, such as ovarian48 and testicular cancer.49 Some of these patients have good prognosis characteristics but unexpectedly relapse many years after initial diagnosis. They are then very responsive clinically, and have good eventual prognosis.

We thank Professors O. B. Eden and J. M. Chessells for comments and advice, Dr A. Borkhardt for help with pilot studies, and Ms B. Deverson for help in preparation of the manuscript.

Supported by the Leukaemia Research Fund Specialist Programme (M.F.G., A.M.F.); Oesterreichische Kinderkrebshilfe (O.A.H., E.R.P.-G., K.F.); and Biomed 1 Concerted Action CT94-1703 (O.A.H.).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Mel F. Greaves, Leukaemia Research Fund Centre, Institute of Cancer Research, Chester Beatty Laboratories, 237 Fulham Rd, London SW3 6JB, United Kingdom; e-mail: m.greaves@icr.ac.uk.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal