Herpes simplex virus (HSV)–based vectors have favorable biologic features for gene therapy of leukemia and lymphoma. These include high transduction efficiency, ability to infect postmitotic cells, and large packaging capacity. The usefulness of HSV amplicon vectors for the transduction of primary human B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) was explored. Vectors were constructed encoding β-galactosidase (LacZ), CD80 (B7.1), or CD154 (CD40L) and were packaged using either a standard helper virus (HSVlac, HSVB7.1, and HSVCD40L) or a helper virus–free method (hf-HSVlac, hf-HSVB7.1, and hf-HSVCD40L). Both helper-containing and helper-free vector stocks were studied for their ability to transduce CLL cells, up-regulate costimulatory molecules, stimulate allogeneic T-cell proliferation in a mixed lymphocyte tumor reaction, and generate autologous cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs). Although helper-containing and helper-free amplicon stocks were equivalent in their ability to transduce CLL cells, a vigorous T-cell proliferative response was obtained using cells transduced with hf-HSVB7.1 but not with HSVB7.1. CLL cells transduced with either HSVCD40L or hf-HSVCD40L were compared for their ability to up-regulate resident B7.1 and to function as T-cell stimulators. Significantly enhanced B7.1 expression in response to CD40L was observed using hf-HSVCD40L but not with HSVCD40L. CLL cells transduced with hf-HSVCD40L were also more effective at stimulating T-cell proliferation than those transduced with HSVCD40L stocks and were successful in stimulating autologous CTL activity. It is concluded that HSV amplicons are efficient vectors for gene therapy of hematologic malignancies and that helper virus–free HSV amplicon preparations are better suited for immunotherapy.

Introduction

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is a malignancy of mature-appearing small B lymphocytes that closely resemble those in the mantle zone of secondary lymphoid follicles.1 CLL remains a largely incurable disease of the elderly; its incidence of more than 20 per 100 000 persons older than 70 makes it the most common leukemia in the United States and Western Europe. CLL, which arises from an antigen-presenting B cell that has undergone a nonrandom genetic event—del(13)(q14q23.1), trisomy 12, del(11)(q22q23), and del(6)(q21q23)2—and clonal expansion, exhibits a unique tumor-specific antigen in the form of surface immunoglobulin. CLL cells have the ability to successfully process and present this tumor antigen, a characteristic that makes the disease an attractive target for immunotherapy.3-6 However, the lack of expression of costimulatory molecules on CLL cells renders them inefficient effectors of T-cell activation, a prerequisite for the generation of antitumor immune responses.7 This failure to activate T cells has been implicated in the establishment of tumor-specific tolerance.8 Reversal of pre-existing tolerance potentially can be achieved by up-regulating a panel of costimulatory molecules (B7.1, B7.2, and ICAM-1)9 through the activation of CD40 receptor–mediated signaling and the concomitant enhancement of antigen presentation machinery.10-13

Application of these insights to gene therapy for CLL has been hampered by difficulties in developing a safe and reliable vector capable of transducing primary leukemia cells. In contrast to tumor cell lines, CLL cells are effectively postmitotic, and only a small fraction actively enter the cell cycle.14 Although both retroviral and adenoviral vectors have been used in different clinical trials for cancer gene therapy, both systems exhibit limitations.15-19 For example, the low levels of integrin receptors for adenovirus on CLL cells mandates the use of high adenovirus titers, preactivation of the CLL cell with IL-4 or anti-CD40/CD40L,20,21 or adenovirus modification with polycations to achieve clinically meaningful levels of transgene expression.22

Gene therapy vectors based on the herpes simplex virus (HSV) offer a number of advantages for gene therapy of CLL.23,24 These include broad cellular tropism, large DNA packaging capacity that allows for expression of multiple genes, high transduction efficiency, and episomal vector genome maintenance which should be less prone to insertional mutagenesis. Historically, the development of HSV vectors for clinical applications has been slowed by the complexities inherent in manipulating a large viral genome (150 kb) coupled with toxicities attributable to HSV-encoded regulatory and structural viral proteins.25

One type of HSV vector, the amplicon, is essentially a eukaryotic expression plasmid that contains the following genetic elements: (1) HSV-derived origin of DNA replication (ori) and packaging sequence (“a” sequence); (2) transcriptional unit driven typically by the HSV-1 immediate early (IE) 4/5 promoter or an alternative promoter followed by an SV-40 polyadenylation site; and (3) bacterial origin of replication and antibiotic resistance gene for propagation inEscherichia coli.25,26 Amplicon plasmids are dependent on helper virus function to provide the replication machinery and structural proteins necessary for packaging amplicon vector DNA into viral particles. Helper packaging function is usually provided by a replication-defective virus that lacks an essential viral regulatory gene. The final product of helper virus–based packaging contains a mixture of varying proportions of helper and amplicon virions. Recently, helper virus–free amplicon packaging methods were developed by providing a packaging-deficient helper virus genome through a set of 5 overlapping cosmids27 or by using a bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) that encodes the entire HSV genome minus its cognate cleavage/packaging signals.28 29

The HSV-based amplicon represents an attractive gene delivery platform for CLL given the known expression of the HSV receptor Hve-A (formerly HVEM/TR2 and ATAR) on B cells.30 In this report, we compared 2 amplicon vector preparations as potential modalities for immunotherapy of CLL—helper virus–packaged amplicon vector stocks manufactured through a replication-defective helper virus deleted in HSV ICP4 and helper virus–free amplicon vector preparations packaged using the BAC-based system. Vector stocks prepared by both packaging methods were used to transduce primary human CLL cells with β-galactosidase (LacZ), B7.1 (CD80), or CD40L (CD154). We studied helper virus–containing and helper virus–free vector stocks for their ability to transduce CLL cells, to function as antigen-presenting cells (APCs), and to stimulate T-cell proliferative response and cytokine release and for their effects on major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I expression in transduced target CLL cells.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and CLL cell transduction using HSV amplicon vectors

Ten-milliliter samples of blood were obtained from 8 patients with established diagnoses of CLL following an approved University of Rochester Human Subject protocol. Peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs) were isolated by density gradient centrifugation on Ficoll-Hypaque Plus (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech AB, Uppsala, Sweden). More than 97% of purified PBLs stained positively for CD19 by flow cytometry. Allogeneic and autologous T cells were purified from donor PBLs through a T-cell enrichment column (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). More than 97% of the purified lymphocytes obtained from the T-cell column were CD3+ by flow cytometry. CLL cells and T cells were maintained in RPMI supplemented with 10% human AB serum. Baby hamster kidney and RR1 cell lines were maintained as previously described.31 The NIH-3T3 mouse fibroblast cell line was originally obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD) and maintained in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) plus 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS).

CLL cells (106) purified by density centrifugation as described above were suspended in 100 μL RPMI with 10% human AB serum in a 1.5-mL Eppendorf tube. An aliquot of 10 to 20 μL HSV amplicon vector was added to the cell suspension and mixed well before incubation at 37°C for 2 to 3 hours. After this initial incubation, 900 μL medium was added to each vial, and the cells were maintained in culture for another 24 hours before they were washed and tested by flow cytometry or used as stimulators in a mixed lymphocyte tumor reaction (MLTR).

Amplicon construction

Coding sequences for E coli β-galactosidase and human B7.1 (CD80) were cloned into the polylinker region of the pHSVPrPUC plasmid32 as previously described.33Murine CD40L (CD154; kindly provided by Dr Mark Gilbert, Immunex, Seattle, WA) was cloned into the BamHI andEcoRI sites of the pHSVPrPUC amplicon vector.

Helper virus–based amplicon packaging

Amplicon DNA was packaged into HSV-1 particles by transfecting 5 μg plasmid DNA into RR1 cells with Lipofectamine as recommended by the manufacturer (Gibco-BRL). After 24-hour incubation, the transfected monolayer was superinfected with the HSV strain 17–derived IE3 deletion mutant virus D30EBA34 at a multiplicity of infection of 0.2. Once cytopathic changes were observed in the infected monolayer, the cells were harvested, freeze-thawed, and sonicated using a cup sonicator (Misonix). Viral supernatants were clarified by centrifugation at 5000g for 10 minutes before repeat passage on RR1 cells. This second viral passage was harvested as above and was concentrated for 2 hours by ultracentrifugation on a 30% sucrose cushion as previously described.35 Viral pellets were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Ca++ and Mg2+ containing) and were stored at −80°C for future use.

Helper virus–free amplicon packaging

Amplicon stocks were also prepared using a modified helper virus–free packaging method. The packaging system uses BAC (kindly provided by C. Strathdee) that contains the HSV genome without its cognate pac signals as a cotransfection reagent with amplicon DNA. Because the amplicon vector has pac signals, only the amplicon genome is packaged. Briefly, on the day before transfection, 2 × 107 baby hamster kidney cells were seeded in a T-150 flask and incubated overnight at 37°C. On the day of transfection, 1.8 mL Opti-MEM (Gibco-BRL), 25 μg pBAC-V2 DNA,28 7 μg pBS(vhs), and 7 μg amplicon vector DNA were combined in a sterile polypropylene tube. Seventy microliters Lipofectamine Plus Reagent (Gibco-BRL) was added to the DNA mix over a period of 30 seconds and allowed to incubate at 22°C for 20 minutes. In a separate tube, 100 μL Lipofectamine (Gibco-BRL) was mixed with 1.8 mL Opti-MEM and also incubated at 22°C for 20 minutes. After the incubations, the contents of the 2 tubes were combined over a period of 30 seconds and incubated for an additional 20 minutes at 22°C. During this second incubation, the media in the seeded T-150 flask were removed and replaced with 14 mL Opti-MEM. The transfection mix was added to the flask and allowed to incubate at 37°C for 5 hours. Then the transfection mix was diluted with an equal volume of DMEM plus 20% FBS, 2% penicillin-streptomycin, and 2 mM hexamethylene bis-acetamide and was incubated overnight at 34°C. The next day, the media were removed and replaced with DMEM plus 10% FBS, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and 2 mM hexamethylene bis-acetamide. The packaging flask was incubated 3 additional days before the virus was harvested and stored at −80°C until purification. Viral preparations were subsequently thawed, sonicated, clarified by centrifugation, and concentrated by ultracentrifugation through a 30% sucrose cushion. Viral pellets were resuspended in 100 μL PBS (Ca++ and Mg2+containing) and stored at −80°C for future use.

Virus titering

Helper virus–containing stocks were titered for helper virus by standard plaque assay methods.36 Amplicon titers for both helper virus–based and helper-free stocks were determined as follows: NIH 3T3 cells were plated in a 24-well plate at a density of 1 × 105 cells/well and infected with the virus. Twenty-four hours after viral infection, the monolayers were washed twice in PBS and either fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained by X-gal histochemistry (HSVlac, 5 mM potassium ferricyanide, 5 mM potassium ferrocyanide, 0.02% NP-40, 0.01% sodium deoxycholic acid, 2 mM MgCl2, and 1 mg/mL X-gal dissolved in PBS) or harvested for total DNA using lysis buffer (100 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 25 mM EDTA, 0.5% SDS) followed by phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. Real-time quantitative PCR was performed on duplicate samples using primers corresponding to the β-lactamase gene present in the amplicon plasmid, according to a previously published method.37 Total DNA was quantitated, and 50 ng DNA was analyzed in a PE7700 quantitative PCR reaction using a designed β-lactamase–specific primer–probe combination multiplexed with an 18S rRNA-specific primer–probe set. The β-lactamase probe sequence was 5′-CAGGACCACTTCTGCGCTCGGC-3′; the β-lactamase sense primer sequence was 5′-CTGGATGGAGGCGGATAAAGT-3′; and the β-lactamase antisense primer sequence was 5′-CGGCTCCAGATTTATCAGCAAT-3′. The 18S rRNA probe sequence was 5′-TGCTGGCACCAGACTTGCCCTC-3′; the 18S sense primer sequence was 5′-CGGCTACCACATCCAAGGAA-3′; and the 18S antisense primer sequence was 5′-GCTGGAATTACCGCGGCT-3′. Helper virus titers (pfu/mL), amplicon expression titers (bfu/mL), and amplicon transduction titers (TU/mL) obtained from these methods were used to calculate amplicon titer and thus standardize experimental viral delivery. Amplicon titers of the various virus preparations ranged from 4 to 5 × 108 bfu/mL, whereas helper titers were in the range of 5 to 15 × 107 pfu/mL.

Mixed lymphocyte tumor reaction assay

CLL cells were transduced with equal transduction units of helper virus–containing or helper virus–free amplicon stocks, irradiated (20 Gy), and used as stimulators (2.5 or 5 × 104 cells/well) with allogeneic normal donor T cells (2 × 105 cells in a final volume of 200 μL) in 96-well flat-bottom plates. All cultures were grown in triplicate. Cells were incubated for 5 days at 37°C in 5% CO2. Cells were pulsed with 1 μCi [3H]-thymidine for the last 18 hours of the culture period before they were transferred to a glass fiber filter, and radioactive counts were measured by liquid scintillation counting. To determine the requirement for MHC class I–tumor antigen and T-cell receptor interaction (Signal 1), CLL cells were infected with equivalent transduction units of HSVlac, HSVB7.1, hf-HSVlac, or hf-HSVB7.1 and were used as stimulators as described above, with or without phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) added to a final concentration of 10 ng/mL.

ELISA for IL-2 and γ-interferon

Culture supernatant (50 μL) from every well of the MLTR plate was collected on day 4 before [3H]-thymidine was added and was used in a standard sandwich ELISA (R&D Systems, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

Generation of anti-CLL–specific cytotoxic T-lymphocyte activity

T cells were isolated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) cells using T-cell enrichment column (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) according to the manufacturer's instructions and cultured at 1 × 106 cells/mL in RPMI with 10% human AB serum in a 6-well plate. Autologous CLL cells either were infected with hf-HSVlac or hf-HSVCD40L or were left uninfected before they were added to the T cells in the 6-well plate at a ratio of 4:1 T cells–CLL cells. IL-2, at a concentration of 100 U/mL, was added to the wells after 3 days in culture. After 1 week in culture, 1 × 106 freshly thawed CLL cells (uninfected, hf-HSVlac or hf-HSVCD40L infected) were added to the T cells, and the culture was maintained for a second week of priming. IL-2 (100 U/mL) was again added to the T-cell culture 3 days later (day 10 of priming). After 2 weeks of priming, the T cells were harvested, washed twice in PBS, and counted. T cells were subsequently tested in a standard chromium-release cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) assay as described below.

Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte assay

After 2 weeks of in vitro priming, T cells were incubated with freshly thawed autologous CLL cells either without or with anti–MHC class I (W6/32) at 10 μg/mL. A cytotoxicity assay was performed by incubating primed T cells with 1 × 104chromium 51Cr-labeled CLL cells in a V-shaped 96-well plate at varying effector-target ratios. Spontaneous release was measured by incubating 51Cr-labeled CLL cells alone, and maximum release was calculated by lysing the cells with 2% Triton-X. After a 6-hour incubation, the supernatant was collected and radioactivity was measured using a γ-counter (Packard Instrument). Mean values were calculated for triplicate wells, and the results were expressed as percentage specific lysis according to the formula: [experimental counts − spontaneous counts]/[total counts − spontaneous counts × 100].

Results

HSV amplicon–mediated gene transfer into CLL cells

The usefulness of HSV-based amplicon vectors for the transduction of primary human B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) was examined. HSV amplicon vectors encoding β-galactosidase (LacZ), CD80 (B7.1), or CD154 (CD40L) were packaged using either a standard helper virus (designated HSVlac, HSVB7.1, and HSVCD40L) or a helper virus–free method (designated hf-HSVlac, hf-HSVB7.1, and hf-HSVCD40L).

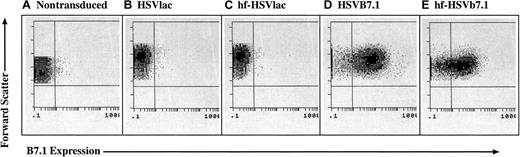

CLL cells were isolated by density gradient centrifugation and 97% or more of the cells stained for CD19, a cell-surface marker for B lymphocytes. The cells were transduced with either HSVlac, HSVB7.1, hf-HSVlac, or hf-HSVB7.1. X-gal histochemistry was performed to detect the β-galactosidase (LacZ) transgene product expressed by HSVlac and hf-HSVlac (data not shown), whereas flow cytometry was performed on CLL cells transduced with equivalent transduction units of HSVB7.1 and hf-HSVB7.1 (Figure 1). More than 70% of the cells stained for either LacZ or B7.1 expression at a multiplicity of infection of 1.0. In agreement with previous studies using HSVlac, expression levels of β-galactosidase peaked at 2 to 3 days and persisted for up to 7 days after infection (data not shown). Hence, both helper virus-containing and helper virus–free amplicon preparations appear to be effective for gene transfer into CLL cells.

HSV amplicon vectors are capable of infecting CLL cells and expressing B7.1.

CLL cells were isolated from human subjects and were left untreated (A) or were transduced with equivalent transduction units of HSVlac (B), hf-HSVlac (C), HSVB7.1 (D), or hf-HSVB7.1 (E). Cell surface expression of B7.1 was assessed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting; representative flow diagrams for each treatment are shown. The y-axis illustrates forward scatter increasing from bottom to top, and the x-axis illustrates positive B7.1 staining increasing in intensity from left to right. Comparable results were obtained from 8 different patients.

HSV amplicon vectors are capable of infecting CLL cells and expressing B7.1.

CLL cells were isolated from human subjects and were left untreated (A) or were transduced with equivalent transduction units of HSVlac (B), hf-HSVlac (C), HSVB7.1 (D), or hf-HSVB7.1 (E). Cell surface expression of B7.1 was assessed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting; representative flow diagrams for each treatment are shown. The y-axis illustrates forward scatter increasing from bottom to top, and the x-axis illustrates positive B7.1 staining increasing in intensity from left to right. Comparable results were obtained from 8 different patients.

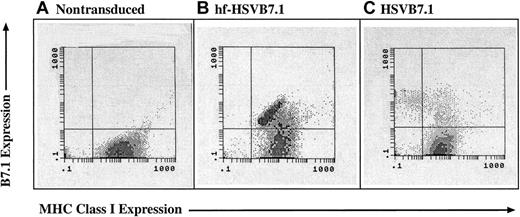

Effect of helper virus on host cell MHC class I expression

Although both vector preparations were able to drive high-level expression of B7.1 in CLL cells, there existed the possibility that helper virus–containing amplicon preparations disrupted MHC class I–mediated antigen presentation. ICP-47, a gene present in the D30EBA helper virus, encodes a protein that blocks TAP-1–mediated peptide loading into MHC class I. Inhibition of MHC class I expression would reduce the usefulness of HSV amplicon vectors for immunotherapeutic strategies. To examine this possibility, CLL cells were transduced with HSVB7.1 or hf-HSVB7.1 and examined by flow cytometry for levels of B7.1 and MHC class I expression. Significant down-regulation of MHC class I in CLL cells transduced with HSVB7.1 was observed compared with MHC class I expression in uninfected cells (Figure2). In contrast, transduction with hf-HSVB7.1 resulted in high levels of B7.1 expression and maintenance of MHC class I surface expression on B7.1-transduced cells. MHC class II levels were unaffected after HSV infection, as detected by flow cytometry (data not shown). These data highlight the role of HSV-encoded factors in the modulation of host immunity and underscore a fundamental difference in the immunotherapeutic potential between helper virus–based and helper virus–free amplicon preparations.

MHC class 1 expression is lost in CLL cells transduced with helper virus–containing amplicon stocks but not with helper virus–free stocks.

CLL cells were isolated from human subjects and were left untreated (A) or were transduced with equivalent transduction units of hf-HSVB7.1 (B) or HSVB7.1 (C). Cell surface expression of B7.1 and MHC class I was assayed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting, and representative flow diagrams for each treatment are shown. The y-axis illustrates positive B7.1 staining increasing from bottom to top, and the x-axis illustrates positive MHC class I staining increasing in intensity from left to right. Transduction with HSVB7.1 results in loss of MHC class I positivity in a significant proportion of B7.1-expressing cells (C), whereas cells infected with hf-HSVB7.1 maintain cell surface expression of both B7.1 and MHC class I. Data are representative of 1 of 4 different samples.

MHC class 1 expression is lost in CLL cells transduced with helper virus–containing amplicon stocks but not with helper virus–free stocks.

CLL cells were isolated from human subjects and were left untreated (A) or were transduced with equivalent transduction units of hf-HSVB7.1 (B) or HSVB7.1 (C). Cell surface expression of B7.1 and MHC class I was assayed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting, and representative flow diagrams for each treatment are shown. The y-axis illustrates positive B7.1 staining increasing from bottom to top, and the x-axis illustrates positive MHC class I staining increasing in intensity from left to right. Transduction with HSVB7.1 results in loss of MHC class I positivity in a significant proportion of B7.1-expressing cells (C), whereas cells infected with hf-HSVB7.1 maintain cell surface expression of both B7.1 and MHC class I. Data are representative of 1 of 4 different samples.

Allogeneic T-cell activation by HSV amplicon–transduced CLL cells

To assess functional differences in antigen presentation after transduction with helper virus-containing or helper virus–free amplicon stocks, the effects of B7.1 transduction on the ability of CLL cells to stimulate T-cell proliferation in an allogeneic MLTR were analyzed. CLL cells were transduced with either HSVlac, HSVB7.1, hf-HSVlac, or hf-HSVB7.1, and transduced cells served as stimulators in an allogeneic MLTR using T cells from a normal donor. hf-HSVB7.1–transduced CLL cells were able to directly stimulate T-cell proliferation (Figure 3). In spite of amplicon-directed expression of B7.1 on 70% or more of the CLL cells, HSVB7.1-transduced CLL cells failed to elicit a T-cell proliferative response, suggesting that the antigen-presenting capacity of the infected CLL cells had been seriously impaired. This could have occurred through the loss of MHC class I expression, as shown in Figure2, or through some other mechanism mediated by the helper virus. PMA was used to provide an extrinsic Signal One to potentially compensate for the adverse effect elicited by the helper virus on CLL cells, thereby allowing transduced B7.1 to elicit a costimulatory signal to T cells. The addition of PMA resulted in significant proliferation in HSVB7.1-infected cells relative to nontransduced or HSVlac-transduced CLL cells. PMA treatment also augmented proliferation in hf-HSVB7.1–transduced CLL cells, suggesting that the full stimulatory potential of T-cell activation by these transduced cells was not fully achieved by helper virus–free vector delivery alone.

CLL cells infected with hf-HSVB7.1 are more efficient at stimulating T-cell proliferation than HSVB7.1-transduced cells.

CLL cells were left untreated (mock infected) or transduced with equivalent transduction units of HSVlac, hf-HSVlac, HSVB7.1, or hf-HSVB7.1. ▪ indicates PMA was added to the reaction at a final concentration of 10 ng/mL, whereas ■ indicates the absence of PMA. [3H]-thymidine uptake data are expressed as counts per minute (cpm). Error bars represent standard deviation. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (P < .001) as determined by single-factor analysis of variance. Data are representative of 4 different patient samples.

CLL cells infected with hf-HSVB7.1 are more efficient at stimulating T-cell proliferation than HSVB7.1-transduced cells.

CLL cells were left untreated (mock infected) or transduced with equivalent transduction units of HSVlac, hf-HSVlac, HSVB7.1, or hf-HSVB7.1. ▪ indicates PMA was added to the reaction at a final concentration of 10 ng/mL, whereas ■ indicates the absence of PMA. [3H]-thymidine uptake data are expressed as counts per minute (cpm). Error bars represent standard deviation. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (P < .001) as determined by single-factor analysis of variance. Data are representative of 4 different patient samples.

IL-2 secretion serves as another correlate to T-cell activation. Supernatants collected from the MLTR samples described above were analyzed using IL-2 ELISA. IL-2 levels were highest when hf-HSVB7.1–transduced CLL cells were utilized as T-cell stimulators (Table 1) in comparison with HSVB7.1 or HSVlac-transduced cells. In other mLTR assays using HSVB7.1-transduced CLL cells, IL-2 secretion was dependent on the provision of Signal One through PMA (data not shown), as was observed with the PMA-mediated rescue of T-cell stimulation (Figure 3).

Interleukin-2 production in MLTR after transduction of chronic lymphocytic leukemia stimulator cells with helper virus–containing and helper virus–free amplicon stocks

| Treatment . | IL-2 (pg/mL) . |

|---|---|

| No virus control | 461 |

| HSVlac | ND |

| hf-HSVlac | 54 |

| HSVB7.1 | 173 |

| hf-HSVB7.1 | 1942 |

| Treatment . | IL-2 (pg/mL) . |

|---|---|

| No virus control | 461 |

| HSVlac | ND |

| hf-HSVlac | 54 |

| HSVB7.1 | 173 |

| hf-HSVB7.1 | 1942 |

IL-2 indicates interleukin-2; ND, not detected.

Up-regulation of costimulatory molecules on CLL cells transduced by HSV amplicons

Engagement of the CD40 receptor on APCs is a critical step in the initiation of an immune response. Up-regulation of costimulatory molecules on CLL cells induced by CD40 receptor signaling correlates with a cell's ability to function as an APC.38 39 We selected the induction of B7.1 expression as a surrogate marker for the morphologic changes induced by CD40 receptor engagement in CLL cells. To test for paracrine and autocrine induction of B7.1, CLL cells were transduced with either hf-HSVCD40L or hf-HSVlac, incubated for 6 days, and subsequently analyzed for the expression of endogenous B7.1. As shown in Figure 4, transduction with hf-HSVCD40L resulted in the up-regulation of B7.1 on CLL cells compared with untransduced and hf-HSVlac–transduced cells. In some experiments, minimal but detectable up-regulation of B7.1 was observed in hf-HSVlac–transduced cells compared with untransduced cells (Figure 4A-B).

hf-HSV amplicon–mediated expression of CD40L leads to an up-regulation of endogenous CD80 (B7.1).

CLL cells were left untreated or were transduced with equivalent transduction units of hf-HSVlac or hf-HSVCD40L. Cell surface expression of B7.1 was assayed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting; representative flow diagrams for each treatment are shown. Cell number quantitation is represented on the y-axis, whereas the x-axis illustrates positive B7.1 staining. hf-HSVCD40L–infected CLL cells (heavy line, both panels) shows preferential up-regulation of B7.1 compared to uninfected CLL cells (A, shaded curve) or CLLs transduced with hf-HSVlac (B, shaded curve). Average percentages of CLL cells staining positive for CD80 for each treatment group were as follows: 3% for uninfected control CLL cells, 11% for hf-HSVlac–infected cells, and 62% for hf-HSVCD40L–infected cells. Data are representative of 4 different patient samples.

hf-HSV amplicon–mediated expression of CD40L leads to an up-regulation of endogenous CD80 (B7.1).

CLL cells were left untreated or were transduced with equivalent transduction units of hf-HSVlac or hf-HSVCD40L. Cell surface expression of B7.1 was assayed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting; representative flow diagrams for each treatment are shown. Cell number quantitation is represented on the y-axis, whereas the x-axis illustrates positive B7.1 staining. hf-HSVCD40L–infected CLL cells (heavy line, both panels) shows preferential up-regulation of B7.1 compared to uninfected CLL cells (A, shaded curve) or CLLs transduced with hf-HSVlac (B, shaded curve). Average percentages of CLL cells staining positive for CD80 for each treatment group were as follows: 3% for uninfected control CLL cells, 11% for hf-HSVlac–infected cells, and 62% for hf-HSVCD40L–infected cells. Data are representative of 4 different patient samples.

The percentage of CLL cells expressing B7.1, CD40L, or both was quantitated by 2-color flow cytometry (Table2). Although infection of CLL cells with HSVCD40L resulted in more than 70% of the cells expressing CD40L, the percentage of cells expressing endogenous B7.1 did not increase appreciably over background levels observed in cells transduced with control HSVlac vector. In contrast, CLL cells transduced with hf-HSVCD40L exhibited a marked enhancement of B7.1 expression relative to either hf-HSVlac– or HSVCD40L-transduced CLL cells. The discrepancy at the level of endogenous B7.1 expression between CLL cells transduced with HSVCD40L and hf-HSVCD40L cannot be attributed to different efficiencies of transduction because both groups expressed similar levels of CD40L. Similar experiments using CD19 expression as an endogenous cell marker confirmed that an inverse relation existed between surface CD19 expression and CD40L expression in cells transduced with helper virus–containing HSVCD40L (data not shown), but not in cells transduced with hf-HSVCD40L. These data suggested that transduction with HSVCD40L resulted in a decrease in expression level of endogenous B7.1.

Percentage of chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells expressing B7.1 and CD40L after transduction with helper virus–containing and helper virus–free amplicon stocks

| Treatment . | CD40L (%) . | B7.1 (%) . | CD40L and B7.1 (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| HSVlac | 2.0 | 12.5 | 0.5 |

| hf-HSVlac | 1.4 | 16.3 | 0.3 |

| HSVCD40L | 77.4 | 13.1 | 7 |

| hf-HSVCD40L | 48.6 | 41.6 | 14.7 |

| Treatment . | CD40L (%) . | B7.1 (%) . | CD40L and B7.1 (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| HSVlac | 2.0 | 12.5 | 0.5 |

| hf-HSVlac | 1.4 | 16.3 | 0.3 |

| HSVCD40L | 77.4 | 13.1 | 7 |

| hf-HSVCD40L | 48.6 | 41.6 | 14.7 |

The ability of CLL cells transduced by CD40L to serve as stimulators in an allogeneic MLTR was examined. CLL cells were transduced with hf-HSVlac, hf-HSVCD40L, HSVlac, or HSVCD40L, and they were incubated for 4 to 6 days to allow for the up-regulation of costimulatory molecules and then were used as stimulators in an allogeneic mLTR. Although similar levels of CD40L expression were observed after transduction with either HSVCD40L or hf-HSVCD40L, cells transduced with hf-HSVCD40L were more potent T-cell stimulators than those transduced with HSVCD40L or control vectors (Figure5).

T-cell proliferation in response to CLL cells infected with hf-HSVCD40L compared with cells transduced with HSVCD40L.

CLL were left untreated (mock infected) or were transduced with equivalent transduction units of HSVlac, hf-HSVlac, HSVCD40L, or hf-HSVCD40L. Cells were then metabolically labeled with [3H]-thymidine in a standard mLTR reaction. [3H]-thymidine uptake data are expressed as counts per minute (cpm). Error bars represent standard deviation. Asterisk indicates statistical significance (P < .001) as determined by single-factor analysis of variance. Data are representative of 4 different patient samples.

T-cell proliferation in response to CLL cells infected with hf-HSVCD40L compared with cells transduced with HSVCD40L.

CLL were left untreated (mock infected) or were transduced with equivalent transduction units of HSVlac, hf-HSVlac, HSVCD40L, or hf-HSVCD40L. Cells were then metabolically labeled with [3H]-thymidine in a standard mLTR reaction. [3H]-thymidine uptake data are expressed as counts per minute (cpm). Error bars represent standard deviation. Asterisk indicates statistical significance (P < .001) as determined by single-factor analysis of variance. Data are representative of 4 different patient samples.

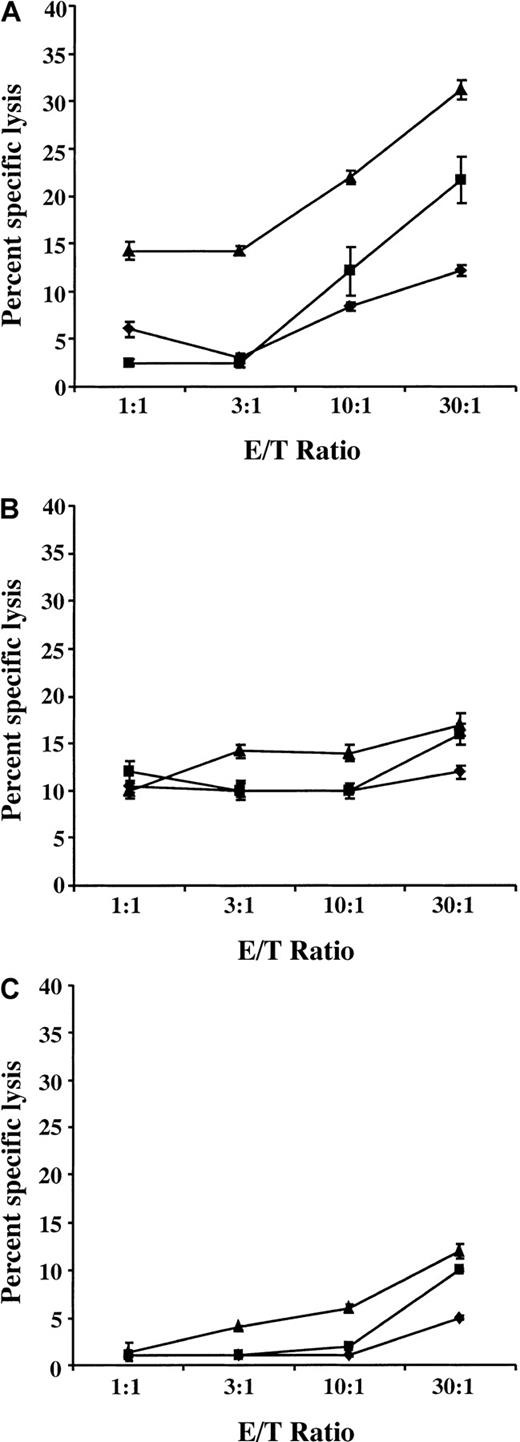

Stimulation of autologous CTL activity by hf-HSVCD40L–transduced CLL cells

Because CLL cells transduced with helper-containing HSV amplicons down-regulated MHC class I expression and were inefficient at stimulating T-cell proliferation in an allogeneic MLTR, we restricted our efforts to generate autologous CTL response to cells transduced with the helper virus–free amplicon stocks. T cells were purified from patients' PBMCs, as described in “Materials and methods,” and were cocultured for 1 week with either freshly isolated CLL cells or with CLL cells transduced with either hf-HSVlac or hf-HSVCD40L at a T-cell–CLL cell ratio of 4:1. IL-2 (100 U/mL) was added for the last 4 days of culture. This protocol was repeated for a second cycle of priming (week 2), after which the T cells were washed and tested for CTL activity in a 4-hour chromium release assay. Three parallel CTL assays were performed using either freshly thawed autologous CLL cells as target, freshly thawed autologous CLL cells with anti–MHC class I blocking antibody (W6/32 at 10 μg/mL), or CLL cells obtained from an unrelated donor. Specific killing was observed using the patient's own CLL cells (Figure 6A). This activity was blunted when anti–MHC class I blocking antibody was added to the assay (Figure 6B). T-cell–mediated killing was essentially undetectable using CLL cells derived from a different donor as targets (Figure 6C), further confirming the specific reactivity of the primed T cells. Supernatant from an autologous T-cell–CLL coculture was assayed for γ-interferon levels by ELISA (Table 3). Higher levels of γ-interferon were detected in supernatants derived from coculture with hf-HSVCD40L–transduced CLL cells compared to nontransduced and hf-HSVlac–transduced control cells.

A specific autologous CTL response can be generated against CLL cells transduced with hf-HSVCD40L stocks.

T cells purified from the PBMCs of a donor with CLL were incubated with control (♦), hf-HSVlac–infected (▪), or hf-HSVCD40L–infected (▴) autologous CLL cells. Cytotoxicity assays were performed by incubating these primed T cells with 51Cr-labeled autologous CLL cells in the absence (A) or the presence (B) of anti-MHC monoclonal antibody, W-6.32, or with 51Cr-labeled allogeneic CLL cells (C) at varying effector-target (E/T) ratios. Supernatant was collected, and radioactivity was measured using a γ counter. Mean values were calculated for the triplicate wells, and the results are expressed as percentage specific lysis according to the following formula: experimental counts − spontaneous counts/total counts − spontaneous counts × 100. Error bars represent the standard deviation of triplicate wells. Data are representative of 1 of 2 experiments.

A specific autologous CTL response can be generated against CLL cells transduced with hf-HSVCD40L stocks.

T cells purified from the PBMCs of a donor with CLL were incubated with control (♦), hf-HSVlac–infected (▪), or hf-HSVCD40L–infected (▴) autologous CLL cells. Cytotoxicity assays were performed by incubating these primed T cells with 51Cr-labeled autologous CLL cells in the absence (A) or the presence (B) of anti-MHC monoclonal antibody, W-6.32, or with 51Cr-labeled allogeneic CLL cells (C) at varying effector-target (E/T) ratios. Supernatant was collected, and radioactivity was measured using a γ counter. Mean values were calculated for the triplicate wells, and the results are expressed as percentage specific lysis according to the following formula: experimental counts − spontaneous counts/total counts − spontaneous counts × 100. Error bars represent the standard deviation of triplicate wells. Data are representative of 1 of 2 experiments.

γ-interferon levels in supernatant derived from cytotoxic T-lymphocyte assay using chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells transduced with helper virus–free amplicon stocks

| Treatment . | γ-interferon (pg/mL) . |

|---|---|

| No virus control | 515 |

| hf-HSVlac | 550 |

| hf-HSVCD40L | 1088 |

| Treatment . | γ-interferon (pg/mL) . |

|---|---|

| No virus control | 515 |

| hf-HSVlac | 550 |

| hf-HSVCD40L | 1088 |

Discussion

The development of safe, reliable, and effective vectors for gene delivery into tumors is prerequisite to translate advances in tumor biology and immunology into clinical practice. The HSV amplicon was chosen as a vector for gene transfer into CLL cells for a number of reasons, central among which is the virus' wide tropism of infection. The mechanism by which HSV gains entry into the target cell has been studied in detail. HSV cell entry requires an initial binding step mediated by viral glycoproteins gC and gB interacting with heparan sulfate chains on the cell surface.40-42 This is followed by penetration through the viral glycoproteins gB and gD and the hetero-oligomer gH-gL.43-46

Cellular receptors for some of these HSV surface glycoproteins have been cloned, including the herpesvirus entry mediator A (Hve-A),30,47,48 Hve-B,49 Hve-C, and Hve-D.50 Hve-A, a 230–amino acid type I transmembrane glycoprotein, is a member of the tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) family, whereas Hve-B, Hve-C, and Hve-D are members of the immunoglobulin superfamily. Hve-A is expressed on T cells, B cells, and monocytes and has recently been identified by flow cytometry on the surfaces of CLL cells.51 Similar to CD40, Hve-A lacks the death domain resident in Fas and TNFR-I and is believed to stimulate T-cell proliferation. The native ligand for Hve-A (HVEM/TR2) has recently been identified as LIGHT,52,53 a type II membrane protein member of the TNF family. Signaling through Hve-A activates NF-κB and AP-1 through interaction with TNF receptor–associated factors (TRAF1, 2, 3, and 5)54 and leads to T-cell activation and proliferation. Although the interaction of HSV gD and Hve-A has been well characterized,55 it remains to be proven whether HSV gD actually signals through Hve-A and stimulates T-cell proliferation in a manner similar to LIGHT or if it only uses Hve-A as a step in a complex viral entry process without transducing a stimulatory signal to the infected cell. Our data suggest the first hypothesis might be at work because HSVlac-infected CLL cells showed modest up-regulation of B7.1 (Figure 4B), which, in some mLTR assays, translated into T-cell proliferation. This suggests that the viral gD expressed on both the amplicon and the helper virus envelope might signal through the HveA (HVEM) on infected cells, induce B7.1 expression, and activate T cells. Although this observation might be of benefit for immune therapy applications using HSV, this might not be the case if the virus is used for long-term gene transfer when evasion of immune surveillance is paramount for long-term expression.

In this paper, data are presented on 2 HSV amplicon vector preparations for potential use in immune therapy of leukemia and lymphoma. Helper virus–containing and helper virus–free amplicon stocks were equivalent at transducing primary CLL cells. However, we found the conventional amplicon packaging methods using helper virus to have a number of potential disadvantages, including exposing the target cell to cytotoxic effects of the helper virus induced by the proapoptotic effects of the immediate-early proteins.56-58 Loss of MHC class I molecules because of helper virus–encoded ICP47 is counterproductive for immune therapy–based strategies. As a result, the ability of tumor cells to provide tumor-specific antigen necessary for the generation of specific CTLs can be impaired.59 60

We used an ICP-4 mutant virus (D30EBA) to provide helper function for amplicon packaging. D30EBA exhibits significantly reduced expression of both early and late viral genes; however, the remaining nondisrupted, immediate early (IE) genes accumulate in the infected cell, and their gene products likely cause the observed problems. One of these IE genes, ICP0, has been shown to arrest cell cycle in the G1/S and G2/M junctions through both p53-dependent and -independent pathways that involve the induction of p21, Gadd45, and mdm-2.61 Loss of MHC class I expression in cells infected with helper virus–containing amplicon stocks is attributable to the interaction of HSV ICP47 gene product with the transporter associated with antigen processing (TAP) protein.59,60 Peptide fragments generated in the cytosol by the proteasome complex are transported by TAP into the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) where they are loaded into MHC class I heavy chain and β2 microglobulin. A kinetically stable peptide–MHC class I complex is released from the ER and exported to the cell surface for recognition by the CD8+ T cells. HSV-1 ICP47 encodes an 88–amino acid polypeptide that interacts with the peptide-binding site on TAP, effectively inhibiting TAP-dependent peptide transport into the ER.62 63 As a result, MHC class I molecules are retained in the ER and are subsequently degraded.

Loss of MHC class I expression was observed in our studies using helper virus–containing stocks, and our attempts to stimulate allogeneic T-cell proliferation using CLL cells transduced with HSVB7.1 were unsuccessful despite high expression of B7.1 on stimulator cells (Figure 1). We hypothesize that the loss of MHC class I on infected cells was partially responsible for the decreased proliferative response despite the costimulatory signal provided by transduced B7.1. Provision of Signal One extrinsically through PMA restored the T-cell proliferative response and IL-2 production. Transduction of CLL cells with helper virus–free HSV amplicon stocks maintained preinfection levels of MHC class I surface expression on transduced cells and was sufficient to stimulate T-cell proliferation even in the absence of PMA.

Helper virus–expressed proteins can additionally derail host cell protein synthesis. Vhs is a 58-kd tegument protein that has an RNase-like activity. In cells infected with HSV-1 or HSV-2, 90% of cellular mRNA and protein synthesis are lost within 3 hours after infection, which leads to a shift in translational preference to virus-encoded transcripts. This grants the virus full access to the host protein machinery without competition from host cell–encoded mRNA species. The vhs protein plays a critical role in allowing HSV to evade the host immune response and subsequently establish latency.64,65 This is supported by multiple lines of evidence. First, dendritic cells (DCs) infected with HSV strains that express a wild-type version of vhs have significantly reduced capacity to differentiate into mature DCs, stimulate allogeneic T cells, release several cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12), and express several surface markers (CD40, CD80, CD83, CD86).66,67 Second, vhs-deficient HSV virus strains are more efficient than wild-type virus as HSV vaccines.68,69Third, in a murine encephalitis model, cells infected with a vhs-null mutant released significantly more IL-1β, the CXC chemokine IL-8, and the CC chemokine MIP-1α.70 Although both helper virus–packaged and helper virus–free amplicon preparations contain vhs protein in virion tegument, only helper virus–containing stocks consist of virions that encode for a genomic copy of the gene that enables de novo synthesis of this cytotoxic protein. Therefore, expression of vhs by the helper virus genome may be responsible for the observed reduction in host cell gene expression, as suggested by the lack of B7.1 expression in response to CD40L stimulation and the loss of CD19 surface expression on transduced cells.

The HSV life cycle involves long periods of latency. To that end, the virus has evolved a number of elaborate and highly efficient mechanisms to avoid detection and elimination by immune cells.71 The same features that allow HSV to avoid detection by the host immune response would be counterproductive with an HSV-based vector to help eradicate an already established tumor with its own immune evasive strategies. This observation has led to our efforts to eliminate the helper virus and was subsequently borne out by our experience using helper virus–containing amplicon preparations. Our findings using helper virus–containing amplicon stocks parallel those reached by 2 other laboratories using HSV vectors to target DCs.66 72Both groups showed that the APC function of DCs was seriously impaired by infection with either replication-deficient or wild-type virus. Deletion of vhs from the viral genome was necessary for restoration of DC-mediated cytokine secretion (IL-6, IL-10, and TNF-α) and surface expression of B7.2 in response to lipopolysaccharide. Even though helper virus–free amplicon stocks contain prepackaged vhs as a tegument protein, infected CLL cells exhibit excellent APC capacity when transduced with hf-HSVB7.1 and hf-HSVCD40L. This indicates that—in contrast to the experience with helper virus–containing amplicon stocks—vhs prepackaged with helper virus–free amplicon is insufficient to interfere with T-cell activation, as demonstrated by enhanced MLTR and by the ability to generate autologous CTL activity using hf-HSVCD40L–transduced CLL cells in vitro.

When considering gene delivery vectors, one must take into account the efficiency of transduction and the potential biologic interactions of the vector proteins with the host cell. The functional discrepancies observed between helper virus–containing and helper virus–free amplicon stocks in spite of comparable transduction efficiency illustrate this point. The use of helper virus–free stocks addresses most of the potential disadvantages seen with helper virus–containing stocks by eliminating the need for helper virus during the packaging process. Extensive safety and efficacy assessments are undoubtedly required before translation to the clinical arena. However, one can envision the potential use of helper virus–free amplicon preparations as tumor-specific vaccines through the transduction of leukemia cells ex vivo with immune effector molecules such as B7.1 and CD40L. An alternative approach would involve direct in situ injection into accessible tumors. Given the wide tissue tropism characteristic of HSV, this approach is equally applicable for nonhematologic malignancies. The large packaging capacity of the HSV amplicon would allow the codelivery of multiple effector molecules for combination immune therapy. Another advantage of the helper virus–free system is that its lack of expression of viral proteins after transduction minimizes the risk for generating anti-HSV immune responses that could abrogate efficacy on repeated vector delivery. This is particularly advantageous when designing clinical applications for a chronic disease such as CLL or non-Hodgkin lymphoma for which treatment would likely require repeated vector administration over long periods of time. In aggregate, helper virus–free HSV amplicon preparations are promising vectors for use in immune-based gene therapy.

We thank Dr Mark Gilbert (Immunex, Seattle, WA) for providing the murine CD40L cDNA and Dr Lewis Lanier (DNAX, Palo Alto, CA) for providing human B7.1 cDNA.

Supported by an LRFA fellowship and a Wilmot Foundation for Cancer Research fellowship (K.A.T.), National Institutes of Health grants 1RO1CA87978-01 (J.D.R.) and R01-NS36420A (H.J.F.), and a Leukemia/Lymphoma Society Translational Research Award (J.D.R.).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Joseph D. Rosenblatt, University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, 601 Elmwood Ave, Rochester, NY 14642; e-mail: joe_rosenblatt@urmc.rochester.edu.

![Fig. 3. CLL cells infected with hf-HSVB7.1 are more efficient at stimulating T-cell proliferation than HSVB7.1-transduced cells. / CLL cells were left untreated (mock infected) or transduced with equivalent transduction units of HSVlac, hf-HSVlac, HSVB7.1, or hf-HSVB7.1. ▪ indicates PMA was added to the reaction at a final concentration of 10 ng/mL, whereas ■ indicates the absence of PMA. [3H]-thymidine uptake data are expressed as counts per minute (cpm). Error bars represent standard deviation. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (P < .001) as determined by single-factor analysis of variance. Data are representative of 4 different patient samples.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/98/2/10.1182_blood.v98.2.287/5/m_h81411280003.jpeg?Expires=1767733293&Signature=Np9bkILMvWyqzI8XARRAl-l5eTALiVJm4ZKjqntRYa~e61qhijkEQjbNrfwWHuLcBnTVRYtoTUJIzwIydrep9Zq7nhYusF6k-NITtn6bdLjuk5MxOwu-bLRL9-4n-XqqKtBR8OuF8b9MNx10ArbSiA6uWuNVjCaBLuqhOcvaYOM9DkfhXoDsuWooh~LnSHBZrzktGCLL4YRpo~FGggIazWpjijr0OAyTN22Qs3weIs~3Y-AqMvVP3SqpEEGK7akkLlyfYtDfxH05248957gOIxKns4ebYnq1mDovY6VmwEQOa---nW7VWIJUct7F503NjdSMyruosUpUmatvegYp1w__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 5. T-cell proliferation in response to CLL cells infected with hf-HSVCD40L compared with cells transduced with HSVCD40L. / CLL were left untreated (mock infected) or were transduced with equivalent transduction units of HSVlac, hf-HSVlac, HSVCD40L, or hf-HSVCD40L. Cells were then metabolically labeled with [3H]-thymidine in a standard mLTR reaction. [3H]-thymidine uptake data are expressed as counts per minute (cpm). Error bars represent standard deviation. Asterisk indicates statistical significance (P < .001) as determined by single-factor analysis of variance. Data are representative of 4 different patient samples.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/98/2/10.1182_blood.v98.2.287/5/m_h81411280005.jpeg?Expires=1767733294&Signature=vj-4CsvD3DmKwB0EAJZpyvKlxSaDzKAo59PPueVc~Ofe0cM5MIAaCoz-~QlAq1mfk2fnWnQf~uhNg9WRsykLARzx7ZmPH2x4cKE8qZFtYesTweoOD~1THNvIXl5N5ofI4hYL-QHiiiCvorlvQQ7owq4bCpcx86ELh4a7knf94K3yrVPlOxBvmeKWvcs0gcm5E3AiDKonA6ksXDoVWn8AHRh1JFrAa8Q1nYOYSiuDT-Q~rrwemgV4dCAZjw5lrcd-C0vxynb4IRqfiAk0m~Q5vngZs41wxvuFLnPzk6YfxWuOa8iKyZ32RMp~~0wdenFzSt6rr52M6tNKQaIi24Y9ng__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal