Abstract

To assess whether fetal hemoglobin (HbF) modulates the adhesion of sickle erythrocytes to endothelium, children with homozygous sickle cell anemia (SS disease) were studied, using this physiologically crucial period to evaluate the relationships between HbF and the major erythrocyte adhesion markers. The mean level of CD36+ erythrocytes was 2.59% ± 2.15% (± SD, n = 40) with an inverse relationship between CD36 positivity and F cells (R = −0.76, P < .000 00 002). In univariate analyses, significant correlations with various hematologic parameters and age were noted. Multiple regression analyses, however, revealed a relationship solely with F cells. Minimal levels of very late activation antigen-4+ (VLA4+) erythrocytes (0.31% ± 0.45%, n = 40) with relationships similar to those noted for CD36+ cells were also observed. The subpopulation of strongly adhesive stress reticulocytes was further assessed, using CD71 as their marker. The mean level of CD71+ erythrocytes was 5.81% ± 4.21%, with statistical correlates in univariate and multivariate analyses similar to those discussed above. When adhesion ratios were evaluated, inverse correlations were noted between basal and plasma-induced adhesion and F-cell numbers (R = −0.54, P < .0005;R = −0.53, P < .0006, n = 39). In addition, in analyses where basal or plasma-induced adhesion was the dependent variable and the independent variables included F cells and the various adhesion-related parameters, significant relationships solely with F cells were noted. The results demonstrate that SS patients with higher levels of F cells have concomitant decreases in the numbers of CD36+, VLA4+, and CD71+ erythrocytes and that these findings translate into less adherent erythrocytes. These findings extend knowledge regarding the protective effects of HbF in the pathophysiology of sickle cell disease.

Introduction

Although the polymerization of hemoglobin S (HbS) in the deoxygenated state in sickle cell disease (SCD) is the watershed event leading to vaso-occlusion, factors that retard the transit time of sickle erythrocytes in the microcirculation, including the cell's adhesive properties, also play a crucial role in this process.1 Since the initial observation by Hebbel et al that sickle red cell–endothelial adherence is correlated with clinical disease severity,2 the last 2 decades have seen a stepwise elucidation of the surface adhesion-related molecules and markers present on the erythrocyte and endothelium that play a role in this process.3,4 Important adhesion-related receptors on the sickle erythrocyte include the integrin α4β1 (very late activation antigen-4 [VLA4])5-7 and CD36 (or glycoprotein IV).6,8,9 Nonreceptor markers include aggregated membrane band 3,10 sulfated glycolipids11 and, most recently, the anionic phospholipid phosphatidylserine.12-15 Endothelial receptors of major importance include the vitronectin receptor αVβ3 integrin8,16,17 and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1.5,7,18 Other endothelial receptors, including CD36 and glycoprotein Ib, may also be of potential significance.3 Ligands in plasma and endothelial matrix proteins that promote adhesion include thrombospondin,19-21 von Willebrand factor,17,22 and laminin,23 and fibrinogen and fibronectin may also be involved.3

A high level of fetal hemoglobin (HbF) in SCD correlates with increased life expectancy and a decrease in the incidence of vaso-occlusive crises.24 The clinical benefits of hydroxyurea therapy in decreasing the rate of painful crises are attributed, for the most part, to its ability to increase the level of HbF. However, a variety of other potential red cell–related modes of action have been postulated, including effects on erythrocyte hydration, cation transport, cell deformability, a decrease in erythrocyte-endothelial adhesion, and a decrease in the expression of erythrocyte adhesion-related markers, including VLA4 and CD36.25-30 Although some of these mechanisms appear to be related to HbF (eg, cell hydration effects),25 in other instances the changes seemingly have occurred prior to a substantial increase in HbF levels (eg, adhesion marker–related events).29 30 Because infants with SCD manifest high levels of HbF, we have used this physiologically important period to evaluate whether potentially important relationships do indeed exist between HbF, the major adhesion-related markers CD36 and VLA4, and the adhesion process. Such relationships might serve to extend our knowledge regarding the protective effects of HbF in the pathophysiology of SCD.

Materials and methods

Materials

For flow cytometric analyses, phycoerythrin (PE)– and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–labeled mouse monoclonal antibodies against human antigens, isotopic-negative control antibodies, and goat antibody against mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) were obtained from Immunotech (Beckman Coulter, Miami, FL), Wallac-Isolab (Akron, OH), or Caltag Laboratories (Burlingame, CA). These antibodies included antiglycophorin A–PE (clone 11E4B7.6 [KC16]), anti-CD36–FITC, anti-CD36–pure (clone FA6.152), anti-CD49d–FITC, anti-CD49d–PE (α chain of VLA4, clone HP2/1), anti-CD71–FITC, anti-CD71–PE (transferrin receptor, clone YDJ1.2.2), anti-HbF–FITC (clone MBF-F), goat antimouse IgG-PE, and isotypic control antibodies (clones 679.1Mc7 and U7.27). Glycophorin A, CD71, and CD49d were used as markers for red cells, stress reticulocytes, and VLA4 positivity, respectively.51Cr-sodium chromate (14.8-44.4 TBq/g) was purchased from NEN (Boston, MA). Tissue culture supplies were obtained from Gibco Laboratories (Grand Island, NY).

Collection of blood

Venous blood was obtained from 17 to 40 infants and children with sickle cell anemia (SS disease) in steady state (ages 2 months to 18 years) and 14 age-matched controls. Patients were considered to be in steady state if they were afebrile, had not been hospitalized or transfused within 8 weeks, and had had no vaso-occlusive episode for at least 10 days prior to or after blood sampling. Blood was drawn by a well-trained phlebotomist using a 2-syringe technique. This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at St Christopher's Hospital for Children and Thomas Jefferson University, both in Philadelphia, PA. Blood was obtained from subjects following informed consent. For minors, patient assent where appropriate was obtained in addition to parental permission. For analyses of F cells (a subpopulation of erythrocytes containing HbF), red cell–associated adhesion markers, and adhesion assays, 1 mL blood was collected using sodium heparin as the anticoagulant and was assessed within 2 to 20 hours after collection. For measurement of hematologic parameters including hemoglobin, white blood cell (WBC) count, and platelet count, 300 μL blood was collected in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid.

Flow cytometric analysis of F cells

F cells were analyzed as previously described.31 32In brief, a sample of packed red cells (20-50 μL) was fixed with 4% formaldehyde (wt/vol) in Dulbecco phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) for 45 minutes at room temperature. The fixed cells were then permeabilized by treating sequentially at −20°C with 1 mL acetone:water (1:1, vol/vol), acetone, and acetone:water (1:1, vol/vol). One million fixed and permeabilized red cells (in a total volume of 100 μL) were incubated with 5 μL FITC-labeled anti-HbF for 30 minutes at room temperature in the dark, washed, and suspended in 1 mL DPBS. The cells were then analyzed immediately in a Becton Dickinson flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, CA) equipped with a 15 mW, 488 nm, air-cooled argon-ion laser and formatted for one-color analysis at a flow rate of 300 to 500 cells per second. Data from 50 000 events were collected and analyzed using CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson). Nonspecific membrane immunofluorescence was determined using fixed, permeabilized red cells stained with FITC-labeled negative isotypic control antibody.

Flow cytometric analysis of adhesive receptors on erythrocytes

One million washed red cells (suspended in a total volume of 100 μL DPBS containing 2% fetal calf serum and 0.1% sodium azide) were incubated with 20 μL PE-labeled antiglycophorin A and 20 μL of either FITC-labeled anti-CD36, anti-CD49d, anti-CD71, or negative isotypic control antibody for 30 minutes at room temperature. The incubation mixture was diluted with 1 mL DPBS, and cells were pelleted at 300g for 10 minutes. Following an additional wash in DPBS, cells were suspended in 1 mL DPBS and analyzed immediately in a Becton Dickinson flow cytometer formatted for 2-color analysis. Fluorescence compensation settings were established using appropriate controls, including cells stained with PE- and FITC-labeled isotopic-negative control antibodies, antiglycophorin A–PE alone, anti-CD36–FITC alone, anti-CD49d–FITC alone, or anti-CD71–FITC alone. Data from 50 000 events were collected for analysis. Percent CD36+, CD49d+, or CD71+ red cells, defined as antiglycophorin A+ events simultaneously stained for CD36, CD49d, or CD71, were determined by setting quadrants on the FL1 (CD36, CD49d, or CD71) and FL2 (glycophorin A) dot plot. Events not staining for glycophorin A did not exceed 0.5%. For the calculation of percent receptor-positive red cells, these latter events were gated out by analysis. Nonspecific membrane immunofluorescence in the double-positive area was determined using cells stained with PE-labeled antiglycophorin A and FITC-labeled negative isotypic control antibody, and these values were subtracted from the respective sample fluorescence.

Flow cytometric analysis of adhesive receptors on F cells and non-F cells

Anti-CD71–PE–, anti-CD49d–PE–, or anti-CD36 plus antimouse IgG– PE–labeled washed red cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained with anti-HbF–FITC as described above and analyzed in a flow cytometer formatted for 2-color analysis. Non–red cell–associated events were gated out as described above, and the marker-positive F cells and non-F cells in the erythrocyte region were then determined using dot plots of FITC and PE fluorescence.

Red cell adhesion assay

Adherence of sickle red cells to endothelial cell monolayers was evaluated using 51Cr-labeled sickle red cells and human retinal capillary endothelial cells (HRCECs) and/or fetal bovine aortic endothelial cells (FBAECs) in the adhesion assay of Hebbel et al.251Cr-labeled sickle erythrocytes were prepared as previously described.33 HRCECs were obtained from human retinas by collagenase digestion, identified, and cultured in minimal essential medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum as previously described.34 FBAECs were isolated, identified, and cultured in minimal essential medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum as previously described.35 Endothelial cells were plated at a density of 200 000 cells per well into wells of 12-well plates, grown to confluence, and then coincubated with51Cr-labeled sickle red blood cells. Adhesion assays were conducted in the absence of plasma (basal adhesion) and in the presence of 10% autologous plasma (plasma-induced adhesion) at 37°C for 45 minutes, and the nonadherent red blood cells were removed. The monolayers were then washed, and adherent red blood cells were determined by 51Cr release following cell lysis.51Cr-labeled control red cells were concomitantly evaluated in adhesion assays in the absence of plasma. The adhesinogenic potential of the patient's red cells was expressed as an adhesion ratio, which was determined by dividing the number of adherent sickle red cells by adherent control red cells.

Analysis of hemoglobin, white blood cells, and platelets

Hemoglobin values, WBC counts, and platelet counts were obtained by routine measurements in a Coulter Counter, model Stk S.

Data analysis

Statistical evaluation was performed using the Sigmastat Statistical Package (Jandel Scientific, San Rafael, CA). All results are presented as the mean ± SD. Both Pearson and Spearman correlation tests were employed to determine the relationship between 2 variables. Both forward and backward stepwise regression analyses were performed in multiple regression models to determine the dependency of the expression of sickle erythrocyte adhesion markers and adhesion on a variety of hematologic parameters.

Results

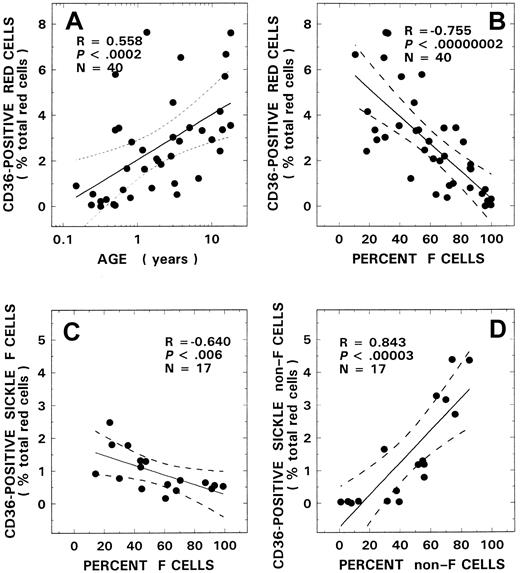

CD36+ erythrocytes and their relationships

CD36+ red cells were absent or present at a very low concentration in blood from control donors, with values remaining at approximately the same level for all ages evaluated (0.05% ± 0.05%, n = 14, mean ± SD). In contrast, in patients with SS disease, a positive correlation was noted between age and CD36 positivity (Figure1A, R = 0.56,P < .0002, n = 40). Although levels of CD36 positivity in infants with SS disease younger than 5 months of age were comparable to control values, significant increases were noted in older children (2.59% ± 2.15%). A striking inverse relationship was also noted between the levels of CD36+ sickle red cells and F-cell numbers (Figure 1B, R = −0.76,P < .000 00 002). No such relationship was observed with control red cells (R = 0.03, P > .90, n = 14). In univariate analyses, correlations were noted between the levels of CD36+ sickle erythrocytes and various other hematologic parameters, including hemoglobin (R = −0.71,P < .000 0005), WBC count (R = 0.58,P < .0001), and platelet count (R = −0.37,P < .02), as assessed using the Pearson test. Multiple regression analyses were therefore performed using both forward and backward regression models to determine the parameter(s) that modulated the levels of CD36+ red cells. In these regression models, percent CD36+ erythrocytes was entered as the dependent variable and F-cell number, age, hemoglobin, WBC count, and platelet count as independent variables. A significant relationship was noted with F cells (power of the test with α at 0.05 = 1.00), which was the only independent variable that stayed in both models. Additional studies (n = 17) were conducted to assess CD36 positivity associated with the F-cell versus non–F-cell fractions. In these studies, although a striking positive correlation was noted with the non–F-cell fraction (Figure 1D, R = 0.84,P < .000 03), an inverse correlation was observed between the F-cell fraction and CD36+ F-cell numbers (Figure 1C, R = −0.64, P < .006).

CD36+ red cells and their relationship to age and F-cell and non–F-cell fractions.

Correlation between CD36+ red cells and age (A) and F-cell number (B) from 40 patients with SS disease are presented. Red cells from 17 patients with SS disease were analyzed for CD36+ F cells (C) and CD36+ non–F cells (D) and their respective relationships to F-cell and non–F-cell fractions. The solid line represents the linear-regression fit to the data, and the dotted lines represent the 99% confidence interval curves.

CD36+ red cells and their relationship to age and F-cell and non–F-cell fractions.

Correlation between CD36+ red cells and age (A) and F-cell number (B) from 40 patients with SS disease are presented. Red cells from 17 patients with SS disease were analyzed for CD36+ F cells (C) and CD36+ non–F cells (D) and their respective relationships to F-cell and non–F-cell fractions. The solid line represents the linear-regression fit to the data, and the dotted lines represent the 99% confidence interval curves.

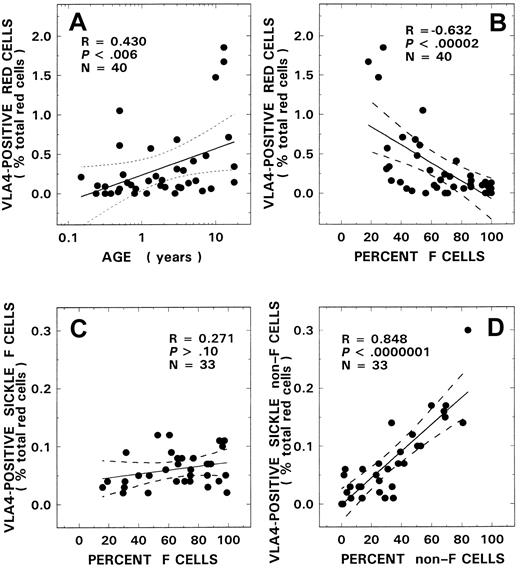

VLA4+ erythrocytes and their relationships

VLA4+ red cells were almost absent in the control donors evaluated in our study (0.05 ± 0.04%, n = 14) with no relationships observed with either age or F-cell number (R = 0.20, P > .50, and R = −0.13,P > .60, respectively). The mean level for VLA4+ red cells measured in patients with SS disease was 0.31% ± 0.45% (n = 40). Relationships similar to those seen with CD36+ sickle erythrocytes were also noted when the VLA4 data were analyzed for both age and F-cell–related correlates. A positive relationship was noted between age and VLA4 positivity (Figure2A, R = 0.43,P < .006), and an inverse correlation was observed with F-cell number (Figure 2B, R = −0.63,P < .000 02). In univariate analyses, correlations were also noted between the levels of VLA4+ sickle erythrocytes and various other hematologic parameters, including hemoglobin (R = −0.58, P < .0001) and WBC count (R = 0.49, P < .002), as assessed using the Pearson test (n = 40). Multiple regression analyses were therefore performed to determine the parameter(s) that modulated the levels of VLA4+ red cells. In these regression models, percent VLA4+ erythrocytes was entered as the dependent variable and F-cell number, age, hemoglobin, and WBC count as independent variables. A significant relationship was noted with F cells (power of the test with α at 0.05 = 0.995), which was the only independent variable that stayed in both regression models. In a subgroup of SS patients (n = 33), we additionally assessed VLA4 positivity associated with both F cells and non-F cells. Although a significant positive correlation was noted with the non–F-cell fraction (Figure2D, R = 0.85, P < .000 0001), no relationship was noted between VLA4+ F cells and the F-cell fraction (Figure 2C, R = 0.27, P > .10).

VLA4+ red cells and their relationship to age and F-cell and non–F-cell fractions.

Correlation between VLA4+ red cells and age (A) and F-cell number (B) from 40 patients with SS disease are presented. Red cells from 33 patients with SS disease were analyzed for VLA4+ F cells (C) and VLA4+ non–F cells (D) and their respective relationships to F-cell and non–F-cell fractions. The solid line represents the linear-regression fit to the data, and the dotted lines represent the 99% confidence interval curves.

VLA4+ red cells and their relationship to age and F-cell and non–F-cell fractions.

Correlation between VLA4+ red cells and age (A) and F-cell number (B) from 40 patients with SS disease are presented. Red cells from 33 patients with SS disease were analyzed for VLA4+ F cells (C) and VLA4+ non–F cells (D) and their respective relationships to F-cell and non–F-cell fractions. The solid line represents the linear-regression fit to the data, and the dotted lines represent the 99% confidence interval curves.

CD71+ erythrocytes and their relationships

Because stress reticulocytes express the highest levels of adhesive markers, in parallel studies, we assessed this subpopulation using CD71 as the marker. Minimal levels of CD71+ red cells were measured in control donors (0.04% ± 0.03%, n = 14), with no correlation observed either with age or with F-cell number (R = −0.14, P > .60, andR = 0.02, P > .90, respectively). Correlations similar to those seen with CD36+ and VLA4+ sickle red cells were also noted when the data from stress reticulocytes were analyzed for age and F-cell–related correlates. Although values in infants with SS disease were not significantly different from control values, levels of CD71+ red cells were increased in the older child (5.81% ± 4.21%), and a significant positive correlation was noted with age (Figure 3A,R = 0.67, P < .000 003, n = 40). A striking inverse correlation was observed between the levels of CD71+ sickle erythrocytes and F-cell number (Figure 3B,R = −0.79, P < .000 00 001). In univariate analyses, correlations were also noted between the levels of stress reticulocytes and various other hematologic parameters, including hemoglobin (R = −0.74,P < .000 00 006), WBC count (R = 0.60,P < .000 05), and platelet count (R = −0.32, P < .05), as assessed using the Pearson test. Multiple regression analyses were therefore performed using both forward and backward regression models to determine the parameter(s) that modulated the levels of stress reticulocytes. In these models, percent CD71+ red cells was entered as the dependent variable and F-cell number, age, hemoglobin, WBC count, and platelet count as independent variables. Although both F-cell number and hemoglobin stayed in the model (R = 0.82,R2 = 0.67, power of the test with α at 0.05 = 1.00), forward regression analyses demonstrated that the predominant variable that influenced circulating levels of stress reticulocytes was F-cell number (R = 0.79,R2 = 0.63, power of the test with α at 0.05 = 1.00), with hemoglobin contributing only minimally to the model (δR2 = 0.04). In a subgroup of patients (n = 34), we additionally assessed CD71 positivity associated with both the F-cell and non–F-cell fractions. Although a significant positive correlation was noted with the non–F-cell fraction (Figure 3D, R = 0.82,P < .000 0001), no relationship was noted with the F-cell fraction (Figure 3C, R = −0.24,P > .10).

CD71+ red cells and their relationship to age and F-cell and non–F-cell fractions.

Correlation between CD71+ red cells and age (A) and F-cell number (B) from 40 patients with SS disease are presented. Red cells from 34 patients with SS disease were analyzed for CD71+ F cells (C) and CD71+ non–F cells (D) and their respective relationships to F-cell and non–F-cell fractions. The solid line represents the linear-regression fit to the data, and the dotted lines represent the 99% confidence interval curves.

CD71+ red cells and their relationship to age and F-cell and non–F-cell fractions.

Correlation between CD71+ red cells and age (A) and F-cell number (B) from 40 patients with SS disease are presented. Red cells from 34 patients with SS disease were analyzed for CD71+ F cells (C) and CD71+ non–F cells (D) and their respective relationships to F-cell and non–F-cell fractions. The solid line represents the linear-regression fit to the data, and the dotted lines represent the 99% confidence interval curves.

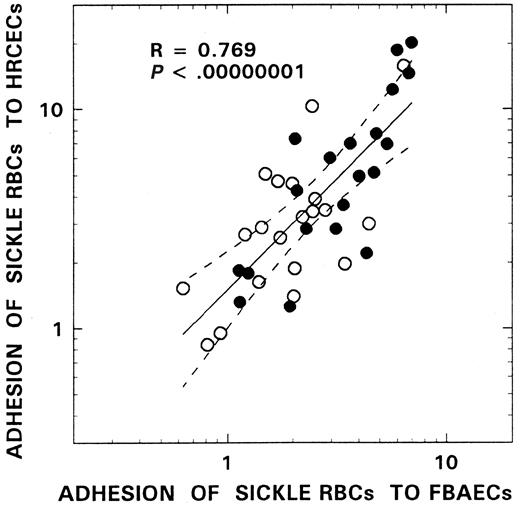

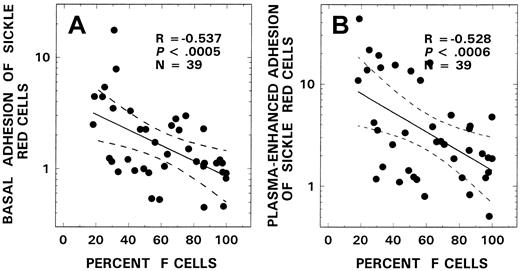

Sickle erythrocyte adhesion and its relationships

We have used both HRCECs and FBAECs to evaluate the adhesinogenic potential of sickle red cells. As depicted in Figure4, using the red cells from 20 patients with SS disease, we assessed both basal and plasma-induced adhesion in simultaneous assays using human retinal capillary endothelium and bovine aortic endothelium and noted a remarkable congruency between the 2 in vitro cell systems (R = 0.77,P < .000 00 001). Because most of the adhesion data from the patients in this study were acquired using bovine endothelial cells, adhesion ratios obtained with the latter cell system were analyzed for relationships with various hematologic parameters. Mean basal and plasma-induced adhesion ratios in the SS patient group were 2.33 ± 2.95 and 6.30 ± 8.42, respectively. Correlations similar to those seen with adhesion markers and stress reticulocytes were also observed when the adhesion data were analyzed for F-cell–related correlates. As shown in Figure5, a significant inverse relationship was observed between F-cell number and both basal (R = −0.54,P < .0005, n = 39, Figure 5A) and plasma-induced adhesion (R = −0.53, P < .0006, n = 39, Figure 5B). Similar relationships with F cells were also noted when the adhesion data from HRCECs were analyzed (R = −0.73,P < .004, n = 20 for basal adhesion andR = −0.83, P < .0003, n = 20 for plasma-induced adhesion). In univariate analyses, correlations were also noted between adhesion and both adhesion markers (n = 31) and various other hematologic parameters (n = 39) as assessed using the Pearson test. Basal adhesion correlated with CD36+ sickle erythrocytes (R = 0.52, P < .003), stress reticulocytes (R = 0.54, P < .002), hemoglobin (R = −0.37, P < .03), WBC count (R = 0.32, P < .05), and age (R = 0.42, P < .008). Multiple regression analyses were therefore performed using both forward and backward regression models to determine the parameter(s) that modulated basal adhesion. In the first model, basal adhesion ratios were entered as the dependent variable and F-cell number, age, hemoglobin, and WBC count as independent variables; in the second, CD36+ sickle red cells, stress reticulocytes, and F-cell number were entered as the independent variables. A significant relationship was noted only with F-cell numbers in both models (R = 0.54,R2 = 0.29, power of the test with α at 0.05 = 0.95; R = 0.59,R2 = 0.35, power of the test with α at 0.05 = 0.946, respectively).

Adhesion relationships between human retinal capillary and bovine aortic endothelial cells.

Red cells from 20 patients with SCD were compared for their adhesion to both HRCECs and FBAECs in the absence (○) and in the presence of plasma (●). The solid line represents the linear-regression fit to the data, and the dotted lines represent the 99% confidence interval curves. The R and Pvalues for the overall relationship, which included both basal and plasma-induced adhesion, are presented in the figure. SimilarR and P values were also noted when the basal and plasma-induced adhesion ratios from these 2 cell systems were analyzed separately (R = 0.652, P < .002 for basal and R = 0.812, P < .000 02 for plasma-induced adhesion).

Adhesion relationships between human retinal capillary and bovine aortic endothelial cells.

Red cells from 20 patients with SCD were compared for their adhesion to both HRCECs and FBAECs in the absence (○) and in the presence of plasma (●). The solid line represents the linear-regression fit to the data, and the dotted lines represent the 99% confidence interval curves. The R and Pvalues for the overall relationship, which included both basal and plasma-induced adhesion, are presented in the figure. SimilarR and P values were also noted when the basal and plasma-induced adhesion ratios from these 2 cell systems were analyzed separately (R = 0.652, P < .002 for basal and R = 0.812, P < .000 02 for plasma-induced adhesion).

Relationship between F-cell numbers and both basal (A) and plasma-induced adhesion (B) from patients with SS disease.

The solid line represents the linear-regression fit to the data, and the dotted lines represent the 99% confidence interval curves.

Relationship between F-cell numbers and both basal (A) and plasma-induced adhesion (B) from patients with SS disease.

The solid line represents the linear-regression fit to the data, and the dotted lines represent the 99% confidence interval curves.

Plasma-induced adhesion also correlated in univariate analyses with CD36+ sickle red cells (R = 0.40,P < .03), VLA4+ sickle erythrocytes (R = 0.42, P < .02), stress reticulocytes (R = 0.54, P < .002), hemoglobin (R = −0.32, P < .05), WBC count (R = 0.39, P < .02), and age (R = 0.52, P < .008). Multiple regression analyses were therefore performed using both forward and backward regression models to determine the parameter(s) that modulated plasma-induced adhesion. In these regression models, plasma-induced adhesion ratios were entered as the dependent variable and F-cell number, age, hemoglobin, and WBC count as independent variables in one model; in the second model, CD36+ sickle red cells, VLA4+ sickle erythrocytes, stress reticulocytes, and F-cell number were entered as independent variables. A significant relationship only with F-cell number was observed in both instances (R = 0.53, R2 = 0.28, power of the test with α at 0.05 = 0.941; R = 0.61,R2 = 0.37, power of the test with α at 0.05 = 0.968, respectively).

Discussion

Clinical observations have long suggested that increased levels of HbF provide beneficial effects in patients with SCD24 and that the cornerstone of this effect is based on the inhibition of sickle hemoglobin polymerization by the glutamine residue at γ-87 of the HbF molecule.36 Evidence for the protective effect of HbF has been reinforced in the last decade by clinical trials demonstrating that hydroxyurea (which has a dose-related effect on enhancing HbF levels) can ameliorate the clinical course of this disease.28,37 However, in these therapeutic trials, it has been noted that clinical benefit may in fact precede the maximum increase in HbF levels. Of the other possible modes of action of hydroxyurea, of special interest to our laboratory is its described effects on red cell adhesion and the adhesion-related erythrocyte markers CD36 and VLA4.27,29 30 When these parameters have been studied in patients with SCD after hydroxyurea therapy, the decrease in erythrocyte adhesion markers and adhesion that was noted by previous investigators occurred prior to substantial increases in the HbF levels in the small groups of patients (n = 3-8) evaluated, suggesting that adhesion and erythrocyte adhesion marker expression was not influenced by HbF levels.

We have approached this issue by alternatively studying a homozygous SS patient cohort with high HbF levels, ie, infants and young children. We have evaluated subjects during this physiologically important period to assess whether HbF may indeed modulate the adhesion process. Our results demonstrate striking inverse correlations between 2 important adhesion-related receptors on the sickle erythrocyte, namely VLA4 (α4β1) and CD36, and F-cell numbers (Figures 1 and 2). Using CD71 as a marker for stress reticulocytes, a similar inverse correlation was noted between these young reticulocytes and F-cell numbers (Figure 3). Additionally, in individual multivariate analyses with CD36+, VLA4+, or CD71+ erythrocytes as the dependent variable and independent variables that included age and various hematologic parameters (F cells, hemoglobin levels, WBC counts, and platelet counts), a significant relationship was noted solely with F-cell numbers. Thus, although we have not demonstrated a direct protective effect of HbF on red cell adhesion receptor expression, we have shown that SS patients with higher levels of F cells have a concomitant decrease in the numbers of adhesinogenic stress reticulocytes and CD36+ and VLA4+ erythrocytes. Additionally, in the individual subject, although F cells were either negative for VLA4 or showed minimal positivity, VLA4 positivity increased with increasing levels of red cells that were negative for HbF (Figure 2C,D). The analyses in the individual subject of F cells versus non-F cells that were CD36+, however, were not as unequivocal. Although CD36 positivity increased with increasing levels of erythrocytes that were negative for HbF (Figure 1D), levels of CD36+ F cells were above baseline. A significant negative correlation was, however, observed between F cells and CD36 positivity (Figure 1C), suggesting that significantly higher levels of F cells (> 60%, ie, equivalent to HbF levels of > 15%38) may be necessary to bring CD36 positivity into a range similar to that of controls. Differential environmental modulation of erythrocyte VLA4 versus CD36 expression has also been noted in clinical studies where red cell CD36-induced changes were of a lesser magnitude than changes in VLA4 expression after hydroxyurea therapy.30

In concomitant studies evaluating adhesion, we have demonstrated, in keeping with the findings discussed above, that a striking inverse correlation was also noted between both basal and plasma-induced adhesion and F-cell numbers (Figure 5). In multivariate analyses with basal or plasma-induced adhesion as the dependent variable and independent variables that included age and the hematologic parameters F cells, hemoglobin levels, WBC counts, and platelet counts, a significant relationship was noted solely with F-cell numbers. Additionally, in analyses where basal or plasma-induced adhesion was the dependent variable and the independent variables included such adhesion-related parameters as CD36, VLA4, and CD71 positivity and F-cell numbers, a significant relationship was noted solely with F cells. These findings demonstrate that SS patients with high levels of F cells not only have a decrease in adhesion marker–positive erythrocytes but that this decrease does indeed translate into erythrocytes that are qualitatively less adhesive in their interaction with endothelium. Because red cell–endothelial adherence was shown by Hebbel in his static adhesion assay to correlate with clinical disease severity,2 3 our observations suggest that besides its inhibition of sickle hemoglobin polymerization, the protective effect of HbF in ameliorating vaso-occlusive symptomatology is in part due to its modulation of the adhesive process.

In summary, our evaluation of infants and children with SS disease has provided data suggesting that HbF may indeed modulate adhesion and the adhesion-related markers VLA4 and CD36. In addition, levels of stress reticulocytes that have the most marked adhesive potential appeared to be similarly modulated by F-cell numbers. The amelioration of clinical symptoms related to vaso-occlusion has previously been noted by 8 weeks after initiation of hydroxyurea therapy in adults with SS disease, but peak increases in F-cell numbers did not occur until approximately 16 to 24 weeks in this study.28Additionally, the linear decrease in VLA4 expression reported by Styles and coworkers continued for 10 weeks after treatment initiation, with the nadir of VLA4 being reached by 20 weeks, whereas changes in HbF levels occurred at a relatively slower rate.30 These spatially juxtaposed observations have been interpreted to signify that adhesion marker expression was not influenced by HbF levels. However, in the multicenter trial of 152 men and women with SS disease treated with hydroxyurea, F-cell measurements did indeed demonstrate a significant increase by 8 weeks after initiation of therapy,28 including a documented range of F-cell values at which, in our study, lower adhesion ratios were noted (Figure 5). Therefore, an amelioration of vaso-occlusive symptomatology in the individual patient that occurred by 2 to 3 months after hydroxyurea could indeed have been due to changes in the levels of F cells via effects on the adhesion process. The present observations in the arena of red cell–endothelial adhesion together with the recently reported demonstration of a protective effect of HbF on erythrocyte microvesicle formation, membrane flip-flop and subsequent phosphatidylserine exposure, and concomitant coagulation activation39 serve to extend the known effects and relationships of fetal hemoglobin. Our data should, in addition, provide the impetus for a thorough evaluation of such biologic markers in the planned future clinical trials of hydroxyurea in infancy and early childhood such that further insights into disease pathophysiology and treatment can be established.

Supported by grants HL51497 and 1P60HL62148 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

B. N. Yamaja Setty, Dept of Pediatrics, Thomas Jefferson University, 1025 Walnut St, Suite 727, Philadelphia PA 19107.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal