Abstract

An 11-year-old boy with hemoglobin sickle disease (HbSD), bilateral stenosis of the intracranial carotid arteries, and moyamoya syndrome had recurrent ischemic strokes with aphasia and right hemiparesis. His parents (Jehovah's Witnesses) refused blood transfusions. After bilateral extracranial–intracranial (EC-IC) bypass surgery, hydroxyurea treatment increased hemoglobin F (HbF) levels to more than 30%. During a follow-up of 28 months, flow velocities in the basal cerebral arteries remained stable, neurologic sequelae regressed, and ischemic events did not recur. This is the first report of successful hydroxyurea treatment after bypass surgery for intracranial cerebral artery obstruction with moyamoya syndrome in sickle cell disease. The patient's religious background contributed to an ethically challenging therapeutic task.

Introduction

Vascular occlusions are the typical complication of homozygous sickle cell disease (SCD). Patients who are double heterozygotes for HbSD (α2β6Val 121 Gln) occasionally have severe occlusive cerebrovascular disease and stroke.1Moyamoya syndrome, characterized by the angiographic findings of bilateral occlusive lesions at the terminal portion of the internal carotid artery and an abnormal vascular network at the cerebral base,2 has been reported in patients with SCD who have had strokes.3-9 Reports about cerebral artery bypass surgery for moyamoya syndrome in SCD5 8 are rare, and no data exist about recurrence rate with or without chronic transfusion after bypass surgery.

We report on the 28-month follow-up of a patient with HbSD and moyamoya syndrome who was treated successfully with bilateral EC-IC bypass surgery and who received only hydroxyurea (HU) as supportive treatment.

Study design

HbSD Los Angeles–Punjab was diagnosed in the patient at the age of 18 months (initial Hb chromatography: HbA2, 2.5%; HbF, 32%; HbS, 29%; HbD, 37%). Double heterozygote HbS (β6Glu-Val) and D (β121Glu-Gln) Los Angeles–Punjab was identified by isoelectric focusing, ion exchange high-pressure liquid chromatography, and DNA analysis. At follow-up visits, when the patient was between the ages of 5 to 10 years, HbF ranged from 4% to 9%. When he was 8 years old, a decrease in school performance was observed, and he had episodes of somnolence and ataxia. A viral infection was followed by a transient right hemiparesis. Clinical examination revealed murmurs over both carotid bifurcations. Transcranial color duplex (TCD) sonography and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) showed high-grade stenosis of the terminal left internal carotid artery, with cross-flow through the anterior and posterior communicating arteries. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed ischemic infarctions of the left caudate nucleus and frontal periventricular white matter. The hemiparesis regressed spontaneously. When he was 9½ and 10 years of age, 2 episodes of transient right hemiparesis occurred. MRI showed additional left-sided infarctions in the callosal body, frontal white matter, and corona radiata. The parents refused blood transfusions for religious reasons. When he was 10 years of age, the patient had an ischemic stroke with aphasia and right hemiplegia a few days after HU treatment was initiated. MRI revealed infarctions of the left frontal supraorbital region and the central gyrus. TCD, MRA, and angiography showed subtotal stenosis of the internal carotid arteries, collateral flow through the posterior communicating arteries and the leptomeningeal collaterals, and abnormal vascular network (moyamoya) at the cerebral base. Judicial permission was obtained for an emergency exchange transfusion against parental will, and, 16 hours after the stroke, the patient received a half blood volume exchange transfusion, which reduced HbSD to 30%.

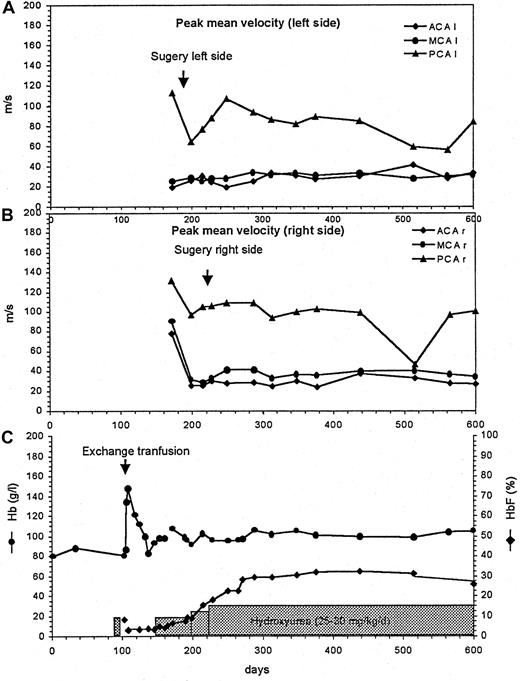

Subsequently, he underwent EC-IC bypass surgery on the left side (anastomosis of the superficial temporal artery to the middle and the anterior cerebral arteries) and, 1 month later, on the right side. HU treatment was increased to 30 mg/kg per day, and HbF rose to 30% to 36% in 3 months (Figure 1). In addition, acetylsalicylic acid was started (2 mg/kg by mouth every second day).

Cerebral artery flow velocities measured by transcranial color duplex sonography.

Hb and HbF concentrations before and after cerebral artery surgery and during HU treatment. Peak mean flow velocities in the left (A) and right (B) anterior (ACA), middle (MCA), and posterior (PCA) cerebral arteries. Total Hb and HbF levels before and during HU treatment (C).

Cerebral artery flow velocities measured by transcranial color duplex sonography.

Hb and HbF concentrations before and after cerebral artery surgery and during HU treatment. Peak mean flow velocities in the left (A) and right (B) anterior (ACA), middle (MCA), and posterior (PCA) cerebral arteries. Total Hb and HbF levels before and during HU treatment (C).

Peak mean blood flow velocities of the anterior, middle, and posterior cerebral arteries were measured monthly (and later bimonthly). During the follow-up, basal cerebral artery flow velocities remained stable (Figure 1). Flow velocities were decreased in both middle cerebral arteries because of the presence of bilateral downstream carotid stenoses and was high in anterior and right posterior cerebral arteries supplying leptomeningeal collaterals. Eighteen months after the last stroke, neither MRI nor MRA showed any new ischemic lesions.

Neuropsychological evaluation 10 months after the stroke indicated the patient had a global IQ in the low-normal range and mildly reduced visual-motor integration. His mental processing was slow, and his school performance was impaired. By 28 months after the last stroke, all neuromotor abnormalities had disappeared, except for inconstant right Babinski sign, mild weakness in the right arm, and asymmetric tendon reflexes.

Results and discussion

The patient reported here is unusual for several reasons. First, the association of SCD and moyamoya disease is rare and, to our knowledge, has never been reported in HbSD. Second, successful HU treatment after neurovascular bypass surgery has never been reported in SCD with moyamoya syndrome. Third, his religious background created an ethically challenging therapeutic task.

Acute cerebral infarction occurs in approximately 7% to 10% of children with SCD, with a peak incidence between 5 and 10 years of age. The initial mortality rate is high (20%), and the recurrence rate is nearly 70% in nontransfused patients.9-11 In HbSD, the incidence of stroke is uncertain. Risk factors include prior transient ischemic attack, abnormal TCD, low steady state Hb level, and high leukocyte count; all were present in our patient.11-13

The standard approach in a patient with SCD who has central nervous system (CNS) abnormalities with or without vasculopathy is to initiate a chronic transfusion program and to monitor cerebral blood flow velocity with TCD.11,12,14 Surgical intervention is now an accepted therapy for children with moyamoya disease who have CNS infarction,2,9 but only 2 descriptions have been reported in the literature of bypass surgery for moyamoya syndrome in SCD patients. One patient underwent encephaloduroarteriosynangiosis (EDAS) that had to be repeated after 18 months; occipital arteries were used the second time.5 In the other report, a bilateral EC-IC bypass procedure was successful; neurologic symptoms improved, but follow-up time was not reported.8 Experience from patients with moyamoya disease shows that direct vascularization with multiple EC-IC bypass, though technically more difficult than EDAS, is more effective at achieving additional perfusion to the affected CNS regions. In a smaller study, this procedure also showed a lower incidence of stroke recurrence.15 16

This patient's parents refused blood transfusions because of their religious beliefs. In view of the vital risk posed by the child's last stroke episode, we obtained a single judicial permission for an emergency exchange transfusion. After EC-IC bypass surgery and in the absence of clear vital emergency, our ethics committee recommended that we follow the will of the parents, and we started HU therapy. This decision took into account the possible negative impact of enforced chronic transfusion treatment on the child's psychosocial development.

Recent therapeutic approaches to SCD have focused on the use of HU to stimulate HbF production. It reduces the frequency of pain crisis, chest crisis, and hospital admission for pain crisis in children with SCD.17-19 No consistent hematopoietic or developmental abnormalities have been observed in a 3-year follow-up of treated children.18 In addition, in children aged 1 to 5 years, a 2- to 3-year follow-up study reported a favorable response and an absence of toxicity, but 2 children had strokes after 1 to 2 years of treatment.20,21 In another study, recurrence occurred in 20% of children who received HU instead of chronic transfusions.22 Therefore, the efficacy of HU in preventing ischemic strokes is still open to question. In comparison with data shown previously,18,20,21 an unusually high increase in HbF to 36% during HU treatment was seen in our patient. In agreement with recent data on chest syndrome in SCD,23high (greater than 30%) HbF levels may be sufficient in specific situations to prevent the progression of CNS vasculopathy. In addition, EC-IC bypass surgery is a valuable therapy in severe CNS vasculopathy. Longer follow-up times and comparative studies are needed for an examination of the efficacy of HU to prevent the progression of CNS disease in SCD.

We thank Marlies Schmid and Chantale Marguet for their help in data analysis and in preparation of the manuscript.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

James Humbert, Department of Pediatrics/Hematology-Oncology Unit, Geneva Children's Hospital, Geneva; Switzerland; e-mail: james.humbert@hcuge.ch.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal