The retinoblastoma (Rb), cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK), and CDK inhibitor genes regulate cell generation, and deregulation can produce increased cell growth and tumorigenesis. Polycythemia vera (PV) is a clonal myeloproliferative disease where the mechanism producing increased hematopoiesis is still unknown. To investigate possible defects in cell-cycle regulation in PV, the expression of Rb and CDK inhibitor gene messenger RNAs (mRNAs) in highly purified human erythroid colony-forming cells (ECFCs) was screened using an RNase protection assay (RPA) and 11 gene probes. It was found that RNA representing exon 2 of p16INK4a and p14ARF was enhanced by 2.8- to 15.9-fold in 11 patients with PV. No increase of exon 2 mRNA was evident in the T cells of patients with PV, or in the ECFCs and T cells from patients with secondary polycythemia. p27 also had elevated mRNA expression in PV ECFCs, but to a lesser degree. Because the INK4a/ARF locus encodes 2 tumor suppressors, p16INK4a and p14ARF with the same exon 2 sequence, the increased mRNA fragment could represent either one. To clarify this, mRNA representing the unique first exons of INK4a and ARF were analyzed by semiquantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction. This demonstrated that mRNAs from the first exons of both genes were increased in erythroid and granulocyte-macrophage cells and Western blot analysis showed that the INK4a protein (p16INK4a) was increased in PV ECFCs. Sequencing revealed no mutations of INK4a or ARF in 10 patients with PV. p16INK4a is an important negative cell-cycle regulator, but in contrast with a wide range of malignancies where inactivation of theINK4a gene is one of the most common carcinogenetic events, in PV p16 INK4a expression was dramatically increased without a significant change in ECFC cell cycle compared with normal ECFCs. It is quite likely that p16INK4a and p14ARF are not the pathogenetic cause of PV, but instead represent a cellular response to an abnormality of a downstream regulator of proliferation such as cyclin D, CDK4/CDK6, Rb, or E2F. Further work to delineate the function of these genes in PV is in progress.

Introduction

Polycythemia vera (PV) is a member of the clonal myeloproliferative disorders, a spectrum of diseases resulting from the transformation of a pluripotent hematopoietic stem cell, and carrying a very high incidence of secondary acute leukemia.1-5 PV is characterized by trilineage marrow hyperplasia with increased production of red cells, granulocytes, and platelets, but it does not involve the immune system. Patients with PV have erythroid progenitors that develop in vitro without the addition of erythropoietin (EPO), displaying either an exquisite sensitivity to EPO or EPO-independent growth, and their blood EPO levels are generally quite low.6-8

Past studies have shown that PV hematopoietic progenitors display hypersensitive responses to a variety of growth factors and cytokines. The burst-forming units-erythroid (BFU-E) are hypersensitive to interleukin-3 (IL-3), stem cell factor (SCF), granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), and insulinlike growth factor.9-14 Despite these abnormal responses, the number of receptors for the growth factors and their dissociation constants are normal.10-16 High levels of Bcl-x were identified in PV cells by one group of investigators and the investigators postulated that this might be responsible for increased survival of PV cells without EPO.17 Whereas a culture of normal erythroid progenitors with orthovanadate, an inhibitor of protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs), resulted in an increased number of erythroid colonies and enhanced protein tyrosine phosphorylation, little enhancement was evident with PV cells, suggesting that patients with PV may have an abnormal PTP activity which promotes increased cell proliferation.18 Further investigations revealed that the total PTP activity in PV erythroid cells was 3-fold higher than in normal cells.19 However, the increase in PTP may represent an effect of the disease rather than a cause. SHP-1 was completely characterized in PV cells and was found to be normal,19,20although one group provided evidence for its underexpression.21 Despite the development of much new knowledge on the control of erythropoiesis, the precise molecular defect that leads to enhanced hematopoiesis in PV is still not apparent. Unlike the situation with chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), where the Philadelphia chromosome and an abnormal, specificBCR-ABL gene arising from a translocation have been identified, no pathognomonic chromosomal or gene abnormality has been found in PV.

Because the proliferation of normal cells is regulated by a combination of stimulatory and inhibitory factors that can respond to external signals in a coordinated manner, a permanent alteration within this regulatory system can lead to abnormal proliferation resulting in tumor formation.22-26 Inactivation of various cell proliferation–regulating proteins (such as the Rb, CDK, and CDK inhibitor proteins), due to gene deletions or mutations, results in enhanced cell generation.24 The INK4a/ARF locus provides important CDK inhibitors that include p16INK4a and p14ARF (p19ARF in the mouse).26-28p16INK4a inhibits CDK4 and CDK6 by directly blocking cyclin D–dependent kinase activity and, thereby, functions to suppress tumor cell growth.26,28 p16INK4a is inactivated by deletions, mutations, and methylation of a CpG island in many primary tumor types such as familial melanomas,29 esophageal carcinosarcomas,30 liver and lung carcinomas,31-33 and lymphomas and leukemias.34-37 Whereas p19ARF also inhibits cell proliferation, it is without direct inhibition of human CDKs and the process is p53-dependent as demonstrated by gene knockouts in mice.26,38 Other CDK inhibitors such as p27 may have a critical role in regulating entry into and exit from the mitotic cycle in response to extracellular signals.24

We previously established a method to purify the early-stage erythroid progenitors (BFU-E) and grow late-stage erythroid colony-forming cells (ECFCs) from human peripheral blood39 and in past studies have repeatedly noticed that PV BFU-E generate many more ECFCs after 8 days of cell culture than normal BFU-E. Because PV is a proliferative disease where a principle problem is erythrocytosis, we have used highly purified erythroid progenitor cells from patients with PV and healthy donors to study the mechanism for increased cellular proliferation in this condition.

Materials and methods

Generation of ECFCs and colony-forming units–granulocyte-macrophage

This method has been previously described.39 In brief, 400 mL of blood was obtained from healthy donors and from patients meeting the established criteria for PV or secondary polycythemia (SP)5,40 who signed consent forms approved by the Vanderbilt Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects and the Nashville Department of Veterans Affairs Research and Development Committee. The characteristics of our patients are listed in Table1. BFU-E were purified by sequential density gradient centrifugation; depletion of platelets and lymphocytes; and removal of adherent cells after overnight culture. A further negative selection and removal of contaminant cells with CD2, CD11b, CD16, and CD45 monoclonal antibodies were performed as previously described.39 41 The day-1 BFU-E were suspended in Iscoves modified Dulbecco medium (IMDM) containing 20% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS); 5% heat-inactivated, pooled, human AB serum; 1% deionized bovine serum albumin (BSA); 5 × 10−5 M 2-mercaptoethanol; 10 μg/mL insulin; 2 U/mL EPO; 50 U/mL IL-3; 100 ng/mL SCF; and streptomycin plus penicillin to generate ECFCs. After 7 days of culture the average purity of day-8 ECFCs was 90% or higher as measured by the plasma clot assay. In some experiments, the BFU-E were incubated for 5 to 18 days.

Patients with polycythemia

| Number . | Sex . | Age . | PCV . | Diagnosis . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PV1 | M | 59 | 47 | polycythemia vera |

| PV2 | F | 69 | 46 | polycythemia vera |

| PV3 | M | 52 | 44 | polycythemia vera |

| PV4 | M | 69 | 49 | polycythemia vera |

| PV5 | M | 68 | 50 | polycythemia vera |

| PV6 | M | 49 | 46 | polycythemia vera |

| PV7 | M | 72 | 45 | polycythemia vera |

| PV8 | F | 46 | 47 | polycythemia vera |

| PV9 | F | 61 | 46 | polycythemia vera |

| PV10 | F | 69 | 48 | polycythemia vera |

| PV11 | M | 74 | 50 | polycythemia vera |

| PV12 | M | 61 | 48 | polycythemia vera |

| SP1 | M | 49 | 54 | hemoglobin with increased oxygen affinity |

| SP2 | M | 48 | 57 | carbon monoxide toxicity |

| SP3 | M | 68 | 59 | testosterone treatment for impotence |

| SP4 | M | 60 | 53 | carbon monoxide toxicity |

| SP5 | M | 70 | 53 | carbon monoxide toxicity |

| SP6 | M | 57 | 52 | carbon monoxide toxicity |

| Number . | Sex . | Age . | PCV . | Diagnosis . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PV1 | M | 59 | 47 | polycythemia vera |

| PV2 | F | 69 | 46 | polycythemia vera |

| PV3 | M | 52 | 44 | polycythemia vera |

| PV4 | M | 69 | 49 | polycythemia vera |

| PV5 | M | 68 | 50 | polycythemia vera |

| PV6 | M | 49 | 46 | polycythemia vera |

| PV7 | M | 72 | 45 | polycythemia vera |

| PV8 | F | 46 | 47 | polycythemia vera |

| PV9 | F | 61 | 46 | polycythemia vera |

| PV10 | F | 69 | 48 | polycythemia vera |

| PV11 | M | 74 | 50 | polycythemia vera |

| PV12 | M | 61 | 48 | polycythemia vera |

| SP1 | M | 49 | 54 | hemoglobin with increased oxygen affinity |

| SP2 | M | 48 | 57 | carbon monoxide toxicity |

| SP3 | M | 68 | 59 | testosterone treatment for impotence |

| SP4 | M | 60 | 53 | carbon monoxide toxicity |

| SP5 | M | 70 | 53 | carbon monoxide toxicity |

| SP6 | M | 57 | 52 | carbon monoxide toxicity |

Patients with PV were treated only with phlebotomy except PV7, who received 1000 mg hydroxyurea per day. PV10 and PV11 received32P in 1997, but subsequently relapsed and were being phlebotomized. All patients with SP were treated only with phlebotomy.

PV indicates polycythemia vera; SP, secondary polycythemia.

Blood mononuclear cells were highly enriched in colony-forming units–granulocyte-macrophage (CFU-GM) using the method for BFU-E except that negative selection was performed without CD45 as previously described,10 but with the addition of CD20. The average purity of CFU-GM was 40 ± 6% by the standard colony-forming assay.10 Culture of these cells was performed in a modified liquid medium for 7 days without EPO.10

Preparation of proliferating T cells

T cells were isolated from the blood of healthy individuals and patients after sheep erythrocyte rosetting during the purification of BFU-E.41 The sheep erythrocytes were lysed in sterile water and the T cells were incubated at 37°C in RPMI 1640 medium including 10% FCS, 40 μg/mL streptomycin, 500 U/mL penicillin, and 3 μg/mL phytohemagglutinin (PHA) for 24 hours. The cells were then washed and resuspended in the same medium without PHA. IL-2 at a concentration of 30 U/mL was added for a 72-hour incubation at 37°C, and then the medium was replaced with fresh IL-2 medium before the cells were collected at 120 hours. Cell-cycle analysis by flow cytometry showed that at least 30% of the T cells were in the S or M phases of the cell cycle (data not shown).

RNA extraction and ribonuclease protection assay

Total RNA was prepared from day-8 ECFCs or T cells using Ultraspec RNAzol (Biotecx Laboratories, Houston, TX) and ribonuclease protection assays (RPAs) were performed using the MAXIscript and RPA II Ribonuclease Protection Assay Kit (Ambion, Austin, TX) according to the manufacturers' protocols. The hCC-2 Multi-Probe Template Set and individual, custom probes for expression of p130, p107, p53, p57, p27, p21, p19, p18, p16, p14/15, and Rb RNA were purchased from Pharmingen (San Diego, CA). The protected transcripts were separated on denaturing polyacrylamide gels, quantified with a laser scanning densitometer, and normalized to the amount of total RNA present in the lane by comparison with the housekeeping gene signals. Gels were developed at varying times so that we could scan the L32 and GADPH housekeeping gene RNAs as internal controls, to correct for variations in loading.

INK4a and ARF sequence analysis

Genomic DNAs from day-8 ECFCs from healthy patients and patients with PV were prepared using the QIAamp Blood Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Four hundred nanograms genomic DNA template was used in each reaction. The INK4a/ARF DNA has a high G:C ratio and the specific fragments could not be successfully amplified with the usual PCR kit, so an Advantage-GC complementary DNA (cDNA) PCR kit was purchased from Clontech (Palo Alto, CA). The reaction solution contained GC cDNA PCR buffer, GC melt, 10 mM each of dATP, dTTP, dCTP, dGTP, DNA polymerase, and specific primers for INK4a/ARF exon 1α, exon 1β, exon 2, and exon 3. The intron oligonucleotide primers were synthesized by Gibco BRL, Life Technologies (Rockville, MD) or Research Genetics (Huntsville, AL) and the sequences of the primers are listed in Table2. Forty cycles were performed and the conditions and cycles were as follows: 5 minutes at 95°C; then 10 cycles with denaturation at 95°C for 1 minute; annealing at 68°C for 1 minute and extension at 72°C for 1 minute; then 10 cycles at 95°C for 1 minute, 64°C for 1 minute, and 72°C for 1 minute; then 20 cycles at 95°C for 1 minute, 60°C for 1 minute, and 72°C for 1 minute; and final elongation at 72°C for 10 minutes. The amplified PCR products were electrophoresed in 2% agarose gels to confirm expected single bands. The PCR products were then cloned into the PCR 2.1 TA cloning vector using the Original TA Cloning Kit (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA) and introduced into competent αH5 cells. The plasmid DNAs were purified using the Qiagen QIAprep Kit. Restriction analyses were performed to determine the presence of the insert and sequence analyses were performed at the Vanderbilt Sequencing Center, Nashville, TN.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and reverse transcription–PCR primer sequences

| Primers . | 5′ to 3′ sequences . | Amplification bp . |

|---|---|---|

| PCR | ||

| Exon 1α | 340 | |

| Forward | GAA GAA AGA GGA GGG GCT G | |

| Reverse | GCG CTA CCT GAT TCC AAT TC | |

| Exon 2 | 394 | |

| Forward | TTC CTT TCC GTC ATG CCG G | |

| Reverse | GTA CAA ATT CTC AGA TCA TCA GTC GTC | |

| Exon 3 | 323 | |

| Forward | GAC CTG GAG CGC TTG AGC GG | |

| Reverse | GTG GCC CTG TAG GAC CTT CGG | |

| Exon 1β | 440 | |

| Forward | TCC CAG TCT GAC GTT AAG GGG | |

| Reverse | GTC TAA GTC GTT GTA ACC CG | |

| RT-PCR | ||

| INK4a (exon 1α to exon 3) | 494 | |

| Forward | ATG GAG CCT TCG GCT GAC TGG C | |

| Reverse | GAC TGA TGA TCT AAG TTT CCC GAG G | |

| ARF (exon 1β to exon 2) | 571 | |

| Forward | GAG TGG CGC TGC TCA CCT CTG G | |

| Reverse | GGG ACC TTC CGC GGC ATC | |

| INK4a | 142 | |

| Forward | ATG GAG CCT TCG GCT GAC TGG C | |

| Reverse | CTG CCC ATC ATC ATG ACC TGG A | |

| ARF | 212 | |

| Forward | CAT GGT GCG CAG GTT CTT GG | |

| Reverse | same as INK4a |

| Primers . | 5′ to 3′ sequences . | Amplification bp . |

|---|---|---|

| PCR | ||

| Exon 1α | 340 | |

| Forward | GAA GAA AGA GGA GGG GCT G | |

| Reverse | GCG CTA CCT GAT TCC AAT TC | |

| Exon 2 | 394 | |

| Forward | TTC CTT TCC GTC ATG CCG G | |

| Reverse | GTA CAA ATT CTC AGA TCA TCA GTC GTC | |

| Exon 3 | 323 | |

| Forward | GAC CTG GAG CGC TTG AGC GG | |

| Reverse | GTG GCC CTG TAG GAC CTT CGG | |

| Exon 1β | 440 | |

| Forward | TCC CAG TCT GAC GTT AAG GGG | |

| Reverse | GTC TAA GTC GTT GTA ACC CG | |

| RT-PCR | ||

| INK4a (exon 1α to exon 3) | 494 | |

| Forward | ATG GAG CCT TCG GCT GAC TGG C | |

| Reverse | GAC TGA TGA TCT AAG TTT CCC GAG G | |

| ARF (exon 1β to exon 2) | 571 | |

| Forward | GAG TGG CGC TGC TCA CCT CTG G | |

| Reverse | GGG ACC TTC CGC GGC ATC | |

| INK4a | 142 | |

| Forward | ATG GAG CCT TCG GCT GAC TGG C | |

| Reverse | CTG CCC ATC ATC ATG ACC TGG A | |

| ARF | 212 | |

| Forward | CAT GGT GCG CAG GTT CTT GG | |

| Reverse | same as INK4a |

RT indicates reverse transcription; bp, base pair.

RT-PCR and semiquantitative RT-PCR

First strand cDNA was synthesized from day-8 normal and PV ECFC RNA using the SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR (Gibco BRL). One microgram total RNA was incubated with the components in the kit following the manufacturer's protocol. The final volume of the reaction was 20 μl. Two micrograms of the cDNA and the Advantage-GC cDNA PCR kit (described above) were used for PCR. The specific primers designed to amplify INK4a and ARF are listed in Table2. First we designed a pair of primers to amplify a 494-bp product, from exon 1α through exons 2 and 3 for INK4a, and a pair of primers to generate a 571-bp product for ARF from exon 1β through exon 2. The conditions for INK4a PCR were as follows: 95°C for 5 minutes; followed by 10 cycles at 95°C for 1 minute, 64°C for 1 minute, and 72°C for 1 minute; then 10 cycles at 95°C for 1 minute, 60°C for 1 minute, and 72°C for 1 minute; then 20 cycles at 95°C for 1 minute, 56°C for 1 minute, and 72°C for 1 minute; then the final step at 72°C for 10 minutes. The conditions for ARF PCR were: 95°C for 5 minutes; then 10 cycles at 95°C for 1 minute, 66°C for 1 minute and 72°C for 1 minute; 10 cycles at 95°C for 1 minute, 64°C for 1 minute and 72°C for 1 minute; then 20 cycles at 95°C for 1 minute, 62°C for 1 minute, and 72°C for 1 minute, followed by the final step at 72°C for 10 minutes. For semiquantitative RT-PCR, the cDNAs were diluted 1:4, 1:16, and 1:64 using the PCR reaction solution and PCR was performed using the same method described above. Table 2 also shows the sequence of shorter primers for amplifying both INK4a (142 bp), from exon 1α through part of exon 2, and ARF (212 bp), from exon 1β through part of exon 2. The PCR conditions were the same as those stated above for the ARF PCR. The products were electrophoresed in 2% agarose gels and quantified with a laser scanning densitometer.

Western blot analysis

Cell extracts were prepared by lysing 107 cells in 100 μl RIPA lysis buffer containing 1% Triton X-100, 20 mM Tris-HC1, ph 7.5, 10% glycerol, 140 mM NaCl, 100 mM sodium fluoride, 10 mM EDTA, 2 mM vanadate, 0.2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and 0.15 U/mL aprotinin at 4°C. Insoluble materials were removed by centrifugation for 20 minutes at 14 000g and 4°C. The samples were quantitated using a Bio-rad protein assay kit II (Bio-rad, Hercules, CA) and were boiled for 5 minutes in an SDS sample buffer before 15% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). The proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose after SDS-PAGE. The blots were incubated for 2 hours at room temperature in Tris-buffered saline with 0.05% Tween-20 (TBST) and 5% nonfat milk and then with anti-p16INK4a overnight at 4°C. The antibodies to p16INK4a were purchased from Santa Cruz (SC-759) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and Pharmingen and the antibody to p14ARF (clone 14P02) was purchased from Neomarkers (Fremont, CA).

Cell-cycle analysis

Day-6 to day-19 cells (1-2 × 106) were washed and the cell pellets were resuspended in propidium iodide solution (0.05 mg/mL in 0.1% sodium citrate) and RNase solution (0.1 mg/mL).42 The cell samples generally were examined within 30 minutes of staining at 4°C by the Vanderbilt Flow Cytometry Lab, but some samples were fixed in 70% ethanol for analysis at a later time.

Results

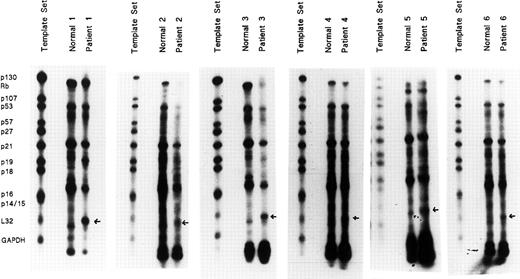

Screen of cell proliferation regulatory gene expression in PV ECFCs

Highly purified day-8 ECFCs were generated from the blood BFU-E of 6 patients with PV and 6 healthy subjects and RNA was extracted. Twenty microgram samples were analyzed for the presence of messenger RNA (mRNA) transcripts using the hCC-2 human cell-cycle Multi-Probe Template Set. This contains templates that can be used for T7 polymerase-directed synthesis of high specific activity [32P]-labeled antisense RNA probes, which can hybridize with target human mRNAs for p130, Rb, p107, p53, p57, p27, p21, p19, p18, p16 exon 2, p14/15, and the housekeeping genes L32 andGAPDH as internal controls. RPAs were performed, and protected transcripts were separated on denaturing polyacrylamide gels and quantified by autoradiography (Figure1). The unprotected template set probes are shown on the left for comparison with the RNase-protected probes following hybridization with normal and PV total RNAs. All samples from the 6 patients with PV showed a well demarcated band with a strikingly greater density than that of the healthy controls. However, because the set contained multiple probes, it was difficult to be sure which specific gene was expressed very highly in these patients, so we next obtained all of the above individual probes from Pharmingen for further studies.

Abnormally high gene mRNA expression in PV erythroid progenitors.

Highly purified day-8 ECFCs were generated from 6 healthy donors and 6 patients with PV. Total RNAs were isolated and 20 μg of RNA were analyzed for the presence of RNA transcripts for p130, Rb, p107, p53, p57, p21, p19, p18, p16, p14/15 related to cell proliferation, using the hCC-2 Multi-Probe Template Set (Pharmingen). L32 andGAPDH were included as internal controls. RNase protection assays (RPAs) were performed with the MAXIscript and RPA II Ribonuclease Protection Assay Kits (Ambion) according to the manufacturer's protocols. Protected transcripts were separated by denaturing polyacrylamide gels and quantified by autoradiography. The band with a strikingly higher expression is indicated by an arrow.

Abnormally high gene mRNA expression in PV erythroid progenitors.

Highly purified day-8 ECFCs were generated from 6 healthy donors and 6 patients with PV. Total RNAs were isolated and 20 μg of RNA were analyzed for the presence of RNA transcripts for p130, Rb, p107, p53, p57, p21, p19, p18, p16, p14/15 related to cell proliferation, using the hCC-2 Multi-Probe Template Set (Pharmingen). L32 andGAPDH were included as internal controls. RNase protection assays (RPAs) were performed with the MAXIscript and RPA II Ribonuclease Protection Assay Kits (Ambion) according to the manufacturer's protocols. Protected transcripts were separated by denaturing polyacrylamide gels and quantified by autoradiography. The band with a strikingly higher expression is indicated by an arrow.

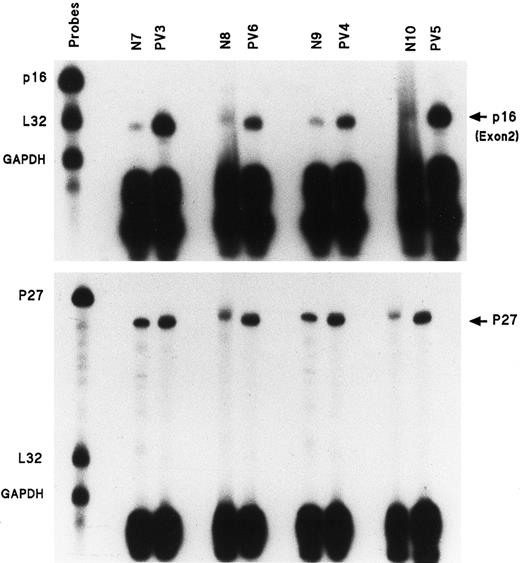

p16 exon 2 gene expression is much greater in PV ECFs

Eleven individual gene probes, including all of those of the above set with internal controls L32 and GAPDH, were used for separate RPAs to measure mRNA expression in PV day-8 ECFCs and normal day-8 ECFCs. No differences were evident with most of the above individual gene probes between normal and PV samples, but the p16 mRNA transcript was significantly enhanced in all 11 studied patients with PV compared with 9 healthy donors. Figure2 (top panel) shows the results of RPAs for p16 exon 2 mRNA expression in ECFCs from 4 healthy donors and 4 patients with PV. Table 3 summarizes these results and the data show that p16 exon 2 transcripts from the 11 patients with PV were quantitatively increased by 2.8- to 15.9-fold as measured by densitometry. We also measured p16 exon 2 mRNA expression in day-10 ECFCs from 3 healthy patients and 4 patients with PV to determine if this increase was limited to a defined stage of erythroid maturation, and we found that no significant difference in p16 mRNA expression was evident, either in normal or PV ECFCs at this time compared with day-8 cells (data not shown).

Enhanced amount of mRNA transcripts for p16 exon 2 and p27 in the ECFCs of 4 patients with PV.

Experiments performed as in Figure 1, but with only p16, L32, and GAPDH gene probes or p27 and L32 and GAPDH.

Enhanced amount of mRNA transcripts for p16 exon 2 and p27 in the ECFCs of 4 patients with PV.

Experiments performed as in Figure 1, but with only p16, L32, and GAPDH gene probes or p27 and L32 and GAPDH.

Expression of protected p16 exon 2 fragment in polycythemia vera and normal erythroid colony-forming cells

| Exp no. . | Normal ECFCs . | PV ECFCs . | p16 density, healthy donors . | p16 density, patients with PV . | % increase in PV . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | N7 | 1 073 | |||

| PV3 | 17 044 | 1 590 | |||

| PV6 | 5 863 | 550 | |||

| N9 | 1 437 | ||||

| PV4 | 5 834 | 410 | |||

| PV5 | 15 275 | 1 063 | |||

| 2 | N11 | 731 | |||

| PV1 | 6 085 | 845 | |||

| 3 | N2 | 630 | |||

| PV2 | 2 668 | 283 | |||

| 4 | N13 | 3 319 | |||

| PV8 | 16 173 | 387 | |||

| 5 | N12 | 2 290 | |||

| PV9 | 8 300 | 362 | |||

| 6 | N8 | 1 225 | |||

| PV7 | 3 478 | 284 | |||

| 7 | N14 | 1 280 | |||

| PV10 | 3 625 | 283 | |||

| N15 | 651 | ||||

| PV11 | 3 707 | 439 |

| Exp no. . | Normal ECFCs . | PV ECFCs . | p16 density, healthy donors . | p16 density, patients with PV . | % increase in PV . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | N7 | 1 073 | |||

| PV3 | 17 044 | 1 590 | |||

| PV6 | 5 863 | 550 | |||

| N9 | 1 437 | ||||

| PV4 | 5 834 | 410 | |||

| PV5 | 15 275 | 1 063 | |||

| 2 | N11 | 731 | |||

| PV1 | 6 085 | 845 | |||

| 3 | N2 | 630 | |||

| PV2 | 2 668 | 283 | |||

| 4 | N13 | 3 319 | |||

| PV8 | 16 173 | 387 | |||

| 5 | N12 | 2 290 | |||

| PV9 | 8 300 | 362 | |||

| 6 | N8 | 1 225 | |||

| PV7 | 3 478 | 284 | |||

| 7 | N14 | 1 280 | |||

| PV10 | 3 625 | 283 | |||

| N15 | 651 | ||||

| PV11 | 3 707 | 439 |

The density of p16 exon 2 assayed by RNase protection assay was quantified with a laser scanning densitometer and normalized to the amount of the total RNA present in the lane by comparison with the housekeeping gene mRNA. The percentage increase in patients with PV was obtained using the density in PV divided by the normal control density in the same gel so that all conditions were the same.

ECFCs indicates erythroid colony-forming cells; PV, polycythemia vera.

p27 gene expression is also increased in PV ECFCs, but is less than p16 expression

The amount of p27 mRNA was delineated in the same 4 normal and 4 PV samples by RPA and the results are shown in Figure 2 (bottom panel). The percentage increases of the p27 gene transcripts in comparison with the p16 exon 2 transcripts, in the same healthy and patient samples, are listed in Table 4. p27 mRNA expression also was enhanced in PV ECFCs, but the degree of increase was much lower than that seen with the p16 exon 2 mRNA.

Increase of p16 exon 2 and p27 messenger RNA in polycythemia vera

| PV sample . | p16, % increase in PV . | p27, % increase in PV . |

|---|---|---|

| PV3 | 1590 | 215 |

| PV6 | 550 | 304 |

| PV4 | 410 | 209 |

| PV5 | 1063 | 402 |

| PV sample . | p16, % increase in PV . | p27, % increase in PV . |

|---|---|---|

| PV3 | 1590 | 215 |

| PV6 | 550 | 304 |

| PV4 | 410 | 209 |

| PV5 | 1063 | 402 |

PV indicates polycythemia vera.

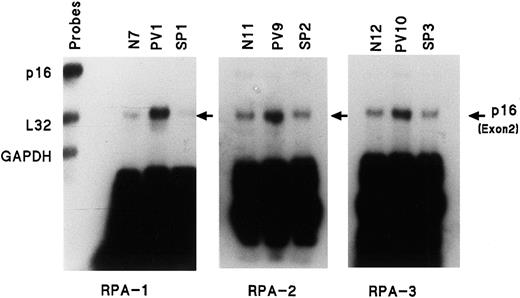

Lack of enhanced p16 exon 2 gene expression in patients with SP

Because p16 mRNA expression is greater than p27 gene expression, we focused our study on p16. PV is a clonal disease with increased red cell production and the increased p16 expression could simply be a manifestation of increased erythropoiesis. SP manifests increased erythropoiesis due to increased EPO production and we obtained ECFCs from the 6 patients with SP listed in Table 1. Figure3 shows a comparison of the amount of the p16 exon 2 transcript from 3 normal, 3 PV, and 3 SP ECFCs and it demonstrates that no increase was present in SP compared with PV. Table5 summarizes 5 experiments comparing the density of the p16 exon 2 transcripts in normal and SP ECFCs and it shows that no difference was present, indicating that the abnormality of p16 expression in PV does not appear to be related to increased erythropoiesis per se.

Enhanced amount of mRNA transcript for p16 (exon 2) in PV ECFCs is not present in secondary polycythemia.

Experiments performed as in Figure 1, but with only p16, L32, and GAPDH gene probes. SP indicates secondary polycythemia.

Enhanced amount of mRNA transcript for p16 (exon 2) in PV ECFCs is not present in secondary polycythemia.

Experiments performed as in Figure 1, but with only p16, L32, and GAPDH gene probes. SP indicates secondary polycythemia.

Expression of protected p16 exon 2 fragment in secondary polycythemia and normal erythroid colony-forming cells

| Experiment no. . | Normal ECFCs . | SP ECFCs . | p16 density, healthy donors . | p16 density, patients with SP . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | N7 | 654 | ||

| SP1 | 412 | |||

| SP6 | 399 | |||

| 2 | N13 | 3319 | ||

| SP5 | 4292 | |||

| 3 | N11 | 2290 | ||

| SP2 | 1645 | |||

| 4 | N9 | 1225 | ||

| SP4 | 533 | |||

| 5 | N12 | 1280 | ||

| SP3 | 1036 |

| Experiment no. . | Normal ECFCs . | SP ECFCs . | p16 density, healthy donors . | p16 density, patients with SP . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | N7 | 654 | ||

| SP1 | 412 | |||

| SP6 | 399 | |||

| 2 | N13 | 3319 | ||

| SP5 | 4292 | |||

| 3 | N11 | 2290 | ||

| SP2 | 1645 | |||

| 4 | N9 | 1225 | ||

| SP4 | 533 | |||

| 5 | N12 | 1280 | ||

| SP3 | 1036 |

Lack of enhanced p16 exon 2 gene expression in activated T cells of patients with PV

To determine if the increased p16 expression was a general manifestation of PV, or was restricted to the myeloproliferative clone, we analyzed activated PV T cells because they are not involved in the clonal PV disease. Blood T cells from healthy, PV, and SP donors were isolated and stimulated with phytohemagglutinin followed by IL-2 in order to provide a state of cell proliferation similar to that of the ECFCs. These activated T cells were then analyzed for p16 mRNA expression. We compared the p16 mRNA levels from activated T cells and day-8 ECFCs of the same patient with PV as well as from activated T cells of a second patient with PV and an SP and healthy donor (Figure 4). Activated PV T cells did not demonstrate enhanced expression of p16 exon 2 mRNA. Thus the PV abnormality does not reside in noninvolved tissues, but instead appears to be related to the clonal hematopoietic disease.

Enhanced expression of mRNA transcript for p16 (exon 2) is not present in activated PV T cells compared with PV ECFCs (left panel) and compared with activated T cells of a healthy or SP donor (right panel).

T cells from the BFU-E purification process were incubated for 24 hours with 3 μg/mL PHA. Cells were then washed and incubated for 5 days with 30 U/mL IL-2. RNA was then isolated and experiments were performed as in Figure 1, but with only p16 (exon 2), L32, and GAPDH gene probes. Activated PV T cells are compared with PV ECFCs (left panel) and with activated T cells of a healthy or SP donor (right panel).

Enhanced expression of mRNA transcript for p16 (exon 2) is not present in activated PV T cells compared with PV ECFCs (left panel) and compared with activated T cells of a healthy or SP donor (right panel).

T cells from the BFU-E purification process were incubated for 24 hours with 3 μg/mL PHA. Cells were then washed and incubated for 5 days with 30 U/mL IL-2. RNA was then isolated and experiments were performed as in Figure 1, but with only p16 (exon 2), L32, and GAPDH gene probes. Activated PV T cells are compared with PV ECFCs (left panel) and with activated T cells of a healthy or SP donor (right panel).

RT-PCR demonstrates that both the p16INK4a and p14ARF transcripts are enhanced in PV ECFCs as well as PV myeloid cells

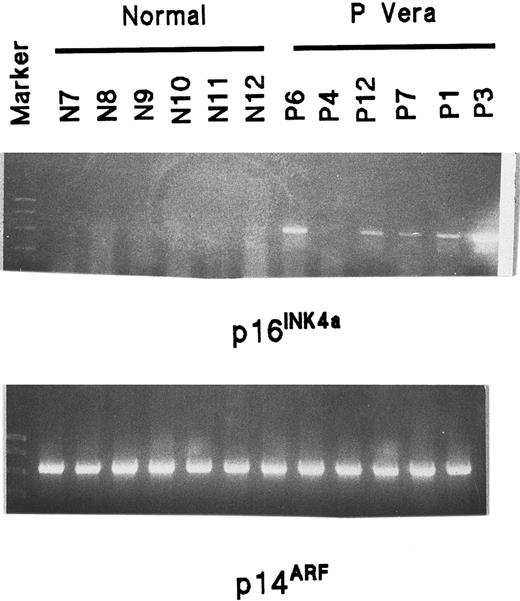

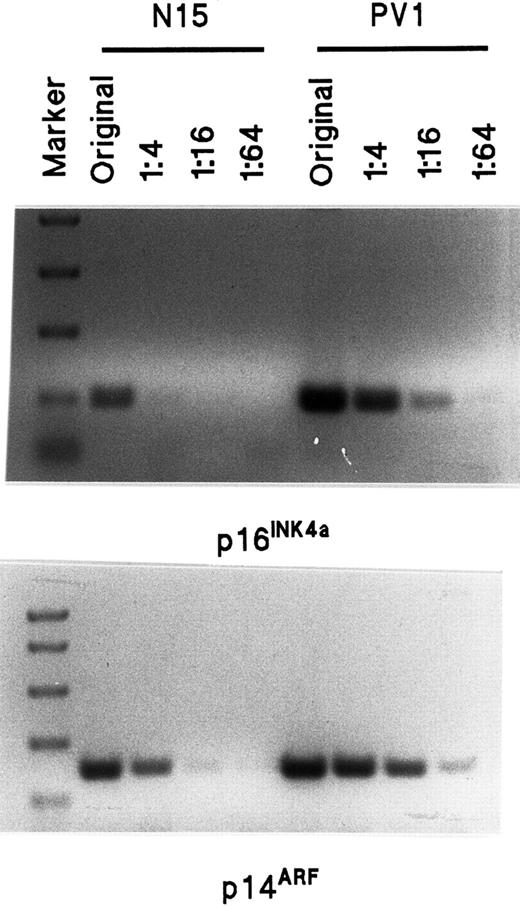

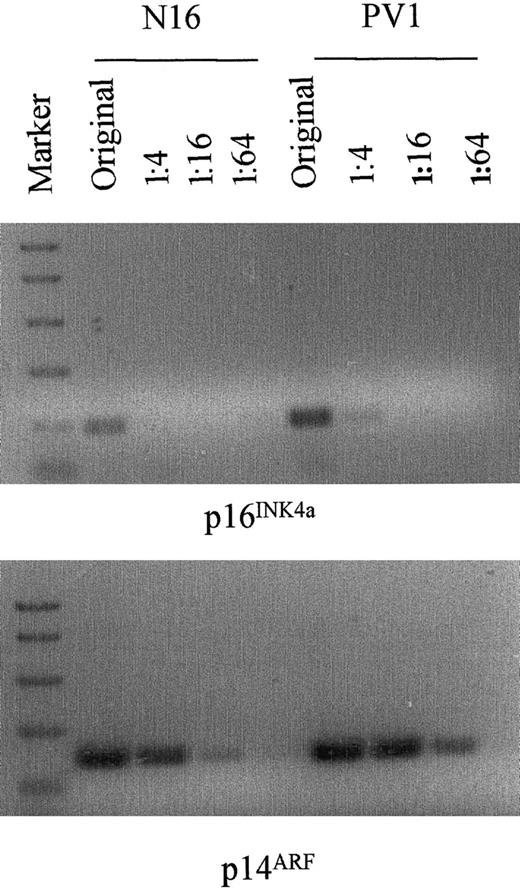

p16 is encoded in the INK4a/ARF locus at chromosome 9p21 and described as p16INK4a.26,28 A second transcript, p14ARF, has been identified at the same locus due to an unprecedented use of an alternative reading frame (ARF) and it also provides potent regulation of cell proliferation.26,28,38,43 The 2 transcripts (α for INK4a and β for ARF) arise from different promoters and have different first exons. They share exons 2 and 3 but, because of distinct reading frames in exon 2, no amino acid identity exists between the 2 products.26 38 Because the probe for the p16 transcript provided by Pharmingen was generated from exon 2 and because p16INK4a and p14ARF share this exon 2 sequence, the protected fragment that we detected could be a part of either one. To clarify this, we performed an analysis of p16INK4a and p14ARF mRNA expression by RT-PCR. Ten normal and 6 PV samples were studied. No amplification of p16INK4a was seen in any of the normal samples, but was clearly present in all PV samples except the sample from patient 4 (Figure5). The expression of p14ARFmRNA was equally strong in both the normal and PV ECFCs and was much greater than p16INK4a expression in both the normal and PV cells. However, because the amplified fragments were very long and the mRNA was GC rich, p16INK4a expression could not be confirmed in the normal ECFCs. Also, because the amplified p14ARF product was very strong in all samples, it needed to be quantified. Therefore, we designed another pair of primers for p16INK4a and p14ARF amplification with specific forward primers, but only a single reverse primer, for each, because both p16INK4a and p14ARF share the same exon 2 sequence. The length of the RT-PCR product for p16INK4a was 142 bp and covered almost the entire exon 1α and part of exon 2, whereas the length of p14ARF was 212 bp and covered almost the entire exon 1β and a part of exon 2. The result of a semiquantitative assay from a normal ECFC extract and a PV ECFC extract is shown in Figure 6 and demonstrates that both p16INK4a and p14ARF had enhanced expression in PV ECFCs compared with the normal control cells. This same experiment was repeated with 3 different normal and PV collections of ECFCs and showed the same results. Similar results were evident when purified CFU-GM were cultured for 7 days and analysis was performed in the same way (Figure 7).

Analysis of p16INK4a and p14ARFmRNA expression in normal and PV ECFCs by RT-PCR.

Information concerning primers and length of products is shown in Table2. The markers show 1000, 750, 500, 300, 150, and 50 bp. The length of p16INK4a is 494 bp and the length of p14ARF is 571 bp.

Analysis of p16INK4a and p14ARFmRNA expression in normal and PV ECFCs by RT-PCR.

Information concerning primers and length of products is shown in Table2. The markers show 1000, 750, 500, 300, 150, and 50 bp. The length of p16INK4a is 494 bp and the length of p14ARF is 571 bp.

Semiquantitative assay of p16INK4a and p14ARF mRNA transcripts by RT-PCR in normal and PV ECFCs.

The sequence of primers is shown in Table 2. The length of the p16INK4a amplification product is 142 bp and the length of p14ARF is 212 bp. The marker sizes on the top panel are 750, 500, 300, 150, and 50 bp whereas the markers on the bottom panel are 1000, 750, 500, 300, and 150 bp. The amount of original total RNA used for the RT-PCR was 80 ng, and 20 ng, 5 ng and 1.25 ng, respectively, were used for the dilutions of 1:4 to 1:64.

Semiquantitative assay of p16INK4a and p14ARF mRNA transcripts by RT-PCR in normal and PV ECFCs.

The sequence of primers is shown in Table 2. The length of the p16INK4a amplification product is 142 bp and the length of p14ARF is 212 bp. The marker sizes on the top panel are 750, 500, 300, 150, and 50 bp whereas the markers on the bottom panel are 1000, 750, 500, 300, and 150 bp. The amount of original total RNA used for the RT-PCR was 80 ng, and 20 ng, 5 ng and 1.25 ng, respectively, were used for the dilutions of 1:4 to 1:64.

Semiquantitative assay of p16INK4a and p14ARF mRNA transcripts by RT-PCR in normal and PV granulocyte-macrophage cells generated from blood CFU-GM.

The method is the same as in Figure 6.

Semiquantitative assay of p16INK4a and p14ARF mRNA transcripts by RT-PCR in normal and PV granulocyte-macrophage cells generated from blood CFU-GM.

The method is the same as in Figure 6.

INK4a and ARF mutation analysis

Because a malfunction of p16 could lead to abnormal feedback and increased expression, each of the 3 exons 1α, 2, and 3 of INK4a and the alternatively spliced exon 1β of ARF were amplified by PCR from genomic DNA of healthy patients and patients with PV using primers complementary to sequences flanking each exon. Sequence analysis for each exon was performed, but no mutation was identified in 10 patients with PV.

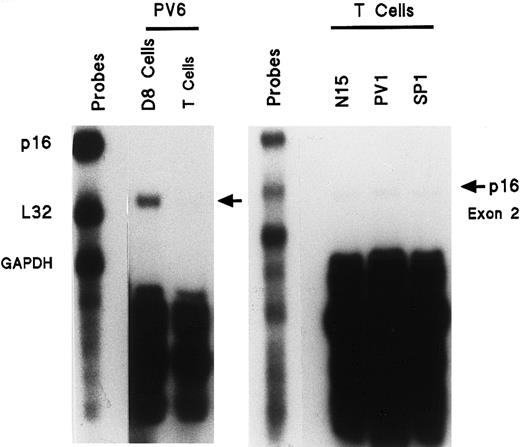

Quantitation of INK4a protein (p16INK4a) in PV ECFCs

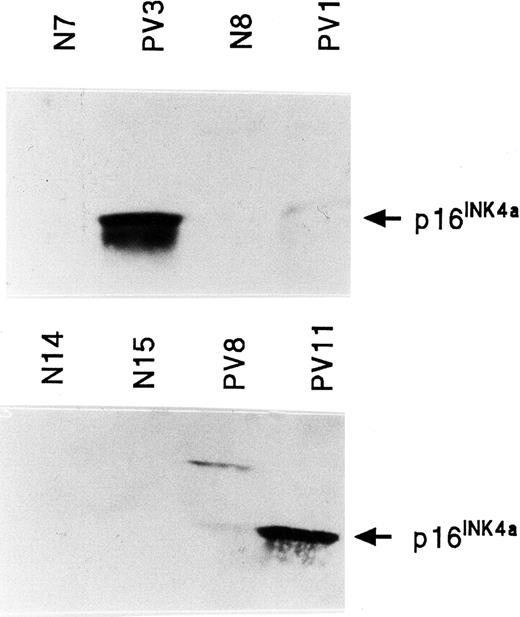

Western blot analysis of p16INK4a was performed on normal and PV ECFC protein. p16INK4a protein was not detectable in 6 normal ECFCs, but was detectable and increased in 4 of 6 PV ECFCs (Figure 8). No stable, reliable results were obtained with the only antihuman ARF protein antibody that was available to us.

INK4a protein (p16INK4a) expression in normal and PV ECFCs.

Two separate Western blots are shown in which PV3 and PV11 have very high levels of p16INK4a protein; PV1 and PV8 have lower levels. p16INK4a was virtually undetectable in all healthy ECFC protein extracts.

INK4a protein (p16INK4a) expression in normal and PV ECFCs.

Two separate Western blots are shown in which PV3 and PV11 have very high levels of p16INK4a protein; PV1 and PV8 have lower levels. p16INK4a was virtually undetectable in all healthy ECFC protein extracts.

Normal and PV ECFC cell-cycle analysis

Cell-cycle analyses on normal and PV day-8 ECFCs were performed. In 5 normal samples the percentage of ECFCs in the G0/G1 stage was 42% ± 12%, S phase was 49% ± 9%, and the G2/M phase was 9% ± 4%. In 4 PV ECFC collections the percentage of cells in the G0/G1 phase was 41% ± 5%, S phase was 53% ± 6%, and the G2/M phase was 6% ± 3%. The percentages of PV and normal cells in the S/G2/M phases were not significantly different. The cell-cycle studies also were carried out on 3 normal and 3 PV ECFC samples in different stages of maturation: day-6, day-8, day-10, day-13, and day-19 cells. The average percentage of S/G2/M stage cells on day 6, day 8, day 10, day 13, and day 19 from healthy individuals was 48%, 67%, 50%, 39%, and 9%, respectively, whereas in PV ECFCs it was 54%, 64%, 53%, 42% and 11%, respectively, which were not statistically significant changes.

Discussion

The INK4a/ARF locus on chromosome 9 is one of the sites mutated most frequently in human cancer.44 We have demonstrated in 11 different PV ECFCs, compared with normal ECFCs, a marked increase in the expression of p16INK4a, a unique inhibitor of cell proliferation and a tumor suppressor. The mRNA also was increased in highly purified PV myeloid cells, but enhanced expression was not present in PV T cells and also was not present in SP ECFCs. Thus the abnormal expression appears to be limited to cells of the myeloproliferative clone of PV, and it is not due to a mutation of the structural components of the gene, which might have decreased the gene's function, as sequence analysis of exons 1α, 2, and 3 in 10 patients with PV showed no mutations of INK4a. In addition, PV ECFCs were shown to have increased expression of p14ARF and p27 mRNA. This is different from the observations made with chronic myeloid leukemia cells where p27 mRNA levels are normal despite relocation of p27 to the cell cytoplasm and inactivation of the protein,45 and is yet another difference of PV from other myeloproliferative diseases.

In the normal cell cycle, control of progression from G1 to S phase is executed predominantly by the gatekeeper Rb protein. In G1, hypophosphorylated Rb binds to the E2F transcription factor, which results in transcriptional repression of E2F-responsive genes and blocks G1/S progression.25,26 In response to growth-promoting signals, a complex of cyclin D and CDK4/6 induces Rb phosphorylation with release of Rb from E2F allowing E2F to transactivate many genes important for mitosis. p16INK4ainhibits the kinase activity of CDK4/6 by changing the conformation of the cyclin-binding site, preventing ATP binding, and thereby producing hypophosphorylation of Rb, which in turn decreases the expression of the E2F-dependent genes.26 Thus p16INK4a is able to block passage from G1 into S and is a bona fide tumor suppressor. Ectopic expression of p16INK4a in human cells induces senescence, which can occur independently of p53.26

Although p14ARF also inhibits the cell cycle, it is without direct inhibition of known CDKs and its effect is p53-dependent as demonstrated by gene knockouts in mice.26,38p14ARF binds to the C-terminal region of MDM2 through its exon 1β-encoding N-terminal domain and promotes the rapid degradation of MDM2, or sequesters MDM2 (sometimes called HDM2 for the human protein) into the nucleolus thereby preventing negative feedback regulation (or degradation) of p53 by MDM2.46,47 This permits p53-induced growth arrest or apoptosis. An ARF mutant that binds MDM2, but does not move it to the nucleolus, is unable to induce p53-dependent cell-cycle arrest.46 Most mutations of exon 2 that disable p16INK4a formation do not decrease the activity of p14ARF suggesting that exon 1β contributes most of the domains necessary for p14ARFfunction.26 Several mitogenic stimuli, E1A, myc, oncogenic ras, V-abl, and E2F-1 upregulate ARF leading to p53 stabilization. Of interest is the fact that mice lacking exons 2 and 3 showed extramedullary hematopoiesis in the absence of anemia.26

Our results indicate that unlike several malignant diseases, PV has no mutation of p16INK4a or p14ARF. In contrast, both genes are expressed in an abnormally high amount in PV ECFCs and this is quite paradoxical, as PV is a disease with increased proliferation. We believe that the large increase in p16INK4a expression in a proliferative disease is most likely due to an abnormality of a downstream protein with which this protein interacts, thereby creating a cellular reaction or feedback for an elevated p16INK4a concentration, rather than an intrinsic abnormality of the p16INK4a promoter, as a primary defect of the latter would not account for the increased cell generation in the disease. Because p16INK4a inhibits cell generation by binding CDK4/6, and because our results demonstrate a p16INK4a increase in PV, it is possible that a mutation of CDK4/6 is present in PV which decreases its binding with p16INK4a and may lead to p16INK4a accumulation. A mutation in familial melanoma, arginine-to-cysteine exchange at residue 24, has been reported, which has a specific effect on the p16INK4a binding domain of CDK4/6, but has no effect on its ability to bind cyclin D and form a functional kinase.48 49 This R24C mutation (single-letter amino acid code) of CDK4 generates an oncogene that is resistant to normal physiologic inhibition by p16INK4a. Therefore, analysis of the structure and function of CDK4/6 may be helpful in revealing the mechanism for the increased cell generation in PV.

Other alternatives for an abnormal elevation of p16INK4amRNA in PV also exist. Li et al50 reported that p16INK4a mRNA accumulates in high levels in cells lacking Rb function and that the transcription of p16INK4a is repressed by Rb. Stott et al51 measured the expression of p16INK4a and p14ARF relative to pRb and p53 in 18 tumor cell lines and primary fibroblast strains. All 8 cell lines, which lacked Rb, had a high expression of p16INK4a. An inverse correlation of p14ARF expression and p53 status in human cell lines was also demonstrated. Thus it is possible that Rb has a mutation producing a loss of function in PV ECFCs so that less binding of E2F to Rb is present, which would result in the activation and expression of a constituency of responder genes that increase cell generation either through increased proliferation or reduced apoptosis. These genes are known to encode products necessary for S-phase progression. Because more cells would enter S phase, the molecular mechanisms controlling cell proliferation might then be activated to increase the CDK inhibitors such as p16INK4a, p27, and p14ARF. Further studies are planned along these lines which we hope will enhance our understanding of the pathogenesis of PV as well as the control of normal erythroid proliferation and differentiation.

The authors thank Maurice Bondurant for his discussions relating to this paper which were very helpful; Hong Ao and Judy Luna, for their technical assistance; and Mary Jane Rich for her expert preparation of the manuscript.

Supported by a Veterans Health Administration Merit Review Grant (to S.B.K.), National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants ROI DK-15555 and 2 T32-DK-07186 (to S.B.K.) and CA-68485 (to Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Sanford B. Krantz, Department of Medicine-Hematology/Oncology, Vanderbilt University, 547 MRB II, 2220 Pierce Ave, Nashville, TN 37232-6305; e-mail:krantz.sanford_b@nashville.va.gov.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal