Abstract

This report is of a 14-month-old girl affected with severe hemophilia A. Both her parents had normal values for factor VIII activity, and von Willebrand disease type 2N was excluded. Karyotype analysis demonstrated no obvious alteration, and BclI Southern blot did not reveal F8 gene inversions. Direct sequencing of F8 gene exons revealed a frameshift-stop mutation (Q565delC/ter566) in the heterozygous state in the proposita only. F8 gene polymorphism analysis indicated that the mutation must have occurred de novo in the paternal germline. Furthermore, analysis of the pattern of X chromosome methylation at the human androgen receptor gene locus demonstrated a skewed inactivation of the derived maternal X chromosome from the lymphocytes of the proband's DNA. Thus, the severe hemophilia A in the proposita results from a de novo F8 gene frameshift-stop mutation on the paternally derived X chromosome, associated with a nonrandom pattern of inactivation of the maternally derived X chromosome.

Introduction

Hemophilia A is an X-linked bleeding disorder caused by the deficiency of factor VIII (FVIII), a cofactor for the activation of factor X by factor IXa. The incidence of the disease is approximately 1 in 5000 males, and hemophilia A is classified as mild, moderate, or severe, depending on the amount of residual factor VIII. The gene encoding FVIII (F8) is located in band Xq28 and spans 186 kilobase (kb).1 The molecular basis underlying hemophilia A is now well characterized, and about half of severely affected hemophiliacs have large genomic inversions resulting from a hot-spot of recombination between a 9.5-kb region in intron 22 (int22h-1) and one of its 2 homologous extragenic copies (int22h-2 and int22h-3).2,3 In the remaining cases, hemophilia A is caused by a large number of different point mutations that could be scattered throughout the 26 exons of theF8 gene.4 Hemophilia A is transmitted by females who are denoted as carriers. These female carriers could have normal or intermediate factor VIII activity (FVIIIC) levels depending on the variable mosaicism of their somatic cells in which either the normal X or the mutated X chromosome is active. Usually these females are asymptomatic because X chromosome inactivation is random with an approximately equal proportion of the 2 populations of somatic cells. However, in rare instances, a nonrandom X chromosome inactivation could result in a symptomatic female in whom the normal X chromosome is predominantly inactive.

In the current report, we investigated a 14-month-old female proposita with severe hemophilia A, and molecular data demonstrated that the severe hemophilia A in this female patient resulted from the occurrence of a de novo frameshift-stop mutation in the F8 gene on the paternally derived X chromosome, associated with a nonrandom pattern of inactivation of the maternally derived X chromosome.

Study design

Case report

The patient was a 14-month-old girl who was the first and unique child of nonconsanguineous parents. Both her parents and grandparents had normal values for FVIIIC, and no family history for bleeding disorders was known. Following an adenoidectomy, the patient developed severe bleeding syndrome with collapsus and profound anemia (hemoglobin 4g/dL). Infusions of vWF-VMC concentrates (Innobrand, Les Ulysses, France) stopped the bleeding immediately. Coagulation studies showed severe FVIIIC deficiency (1%) with normal vWF:Ag and vWF:RCo levels (respectively, 80% and 100%). A type 2N von Willebrand disease (vWD) was excluded, as the binding capacity of FVIII by von Willebrand factor (vWF) was normal, and all these results allowed a diagnosis of hemophilia A to be made.5

FVIII binding assay to vWF

FVIII binding to vWF assay was performed as previously described5 with some modifications: recombinant FVIII (Recombinate, Baxter, San Francisco, CA) was used as a source of exogenous FVIII; vWF bound to the microplate wells and FVIII bound to immobilized vWF were quantified with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated polyclonal antibodies, respectively anti-vWF (DAKO, Copenhagen, Denmark) and anti-FVIII (Kordia, Leiden, The Netherlands). The results were expressed in the amount of FVIII bound as a function of vWF immobilized. Slopes of regression lines obtained for normal and tested plasmas were compared.

Cytogenetic studies

Karyotyping of blood lymphocytes from the proposita and her parents were performed, using standard and high-resolution procedures.

Molecular F8 gene studies

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood lymphocytes by a standard procedure and after informed consent of all the family members. BclI Southern blot was performed as previously reported, using the 0.9-kb fragment from plasmid p482.6 as a probe.2 3

For denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis, the 26 exons and flanking intronic regions were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with GC-clamped sense and anti-sense primers as previously reported.6

GC-clamped PCR products were loaded onto a 6% polyacrylamide gel containing a linear gradient of urea and formamide and were electrophoresed according to the conditions previously described.6

Analysis of the 2 microsatellite repeats in introns 13 and 22, the intron 18 BclI restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP), the XbaI RFLP in intron 22, and the TaqI variable tandem repeat polymorphism at the DXS52 locus were performed as previously described.7-10

X chromosome inactivation

Analysis of X chromosome inactivation was performed as described elsewhere.11 Genomic DNA samples were digested with the methylation-sensitive enzyme HpaII (Boehringer Mannheim, Meylan, France) and were subjected to PCR amplification of the highly polymorphic CAG-repeat sequence in the first exon of the human androgen receptor gene (HUMARA), with specific fluorescent primers. The PCR products, both before and after HpaII digestion, were electrophoresed on an automated DNA sequencer (model ABI 377; Applied Biosystems, Warrington, United Kingdom) and were analyzed by GeneScan software (Applied Biosystems).

Analysis of the X inactive specific transcript (XIST) promoter sequence

DNA from the proposita and her mother were amplified, using the appropriate forward and reverse primers previously used.12,13 Each PCR product was purified and sequenced on both strands, using the Big Dye Terminator sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems) and was resolved on the automatic DNA sequencer. Nucleotide sequences were compared with the nucleotide sequence reported by Hendrich et al.12

Results and discussion

Hemophilia A affects males, whereas females are generally spared. However, there are a variety of potential genetic mechanisms that could lead to phenotypic expression of very low FVIIIC levels in females.14 These mechanisms involve, in some cases, the gene of vWF, resulting either in a quantitative defect or in a functional/structural defect of vWF that is essential for FVIII transport and stability.15 However, in the majority of cases, it is the gene coding for the factor VIII that is directly altered. The genetic mechanisms characterized so far include (1) abnormalities of the X chromosome in structure or in number16,17; (2) homozygosity for a F8mutation, mostly when consanguinity is present18,19; (3) concomitant occurrence of 2 de novo F8mutations20; and (4) most frequently, a selective inactivation of the normal X chromosome in a heterozygous female.21 The female patient that we studied showed normal levels of vWF and normal fixation of factor VIII to vWF, therefore eliminating 2N vWD.15 High-resolution karyotype analysis demonstrated a 46, XX karyotype without obvious structural abnormalities. Polymorphism analysis in the family with several markers close to and within the F8 gene confirmed that the female proposita inherited 2 distinct X chromosomes from each of her parents (Figure 1A). Subsequently the first and the second mechanisms cited above were excluded as the underlying cause of severe hemophilia A in this child. Therefore, the X chromosome inactivation patterns in the peripheral blood of the patient and her parents were analyzed at the HUMARA gene and were quantitated using a fluorescent PCR assay previously described.11 The HUMARA gene contains in its first exon a highly polymorphic CAG repeat that allows the 2 X chromosomes of females informative at the locus to be distinguished. Close to this CAG repeat are located 2 HpaII sites that resist cleavage by methylation-sensitive restriction enzymeHpaII on the methylated-inactive X chromosome, whereas these sites are cleaved by HpaII on the unmethylated active X chromosome.22 Therefore, PCR products afterHpaII digestion could be obtained only from the inactive X chromosome. In a normal female in whom X inactivation is random, an approximately equal portion of both the maternally and paternally derived inactive X chromosomes remain undigested and both HUMARA CAG repeat alleles will be amplified. Alternatively, if X chromosome inactivation is nonrandom, only one allele corresponding to the inactive X chromosome is expected to be amplified.

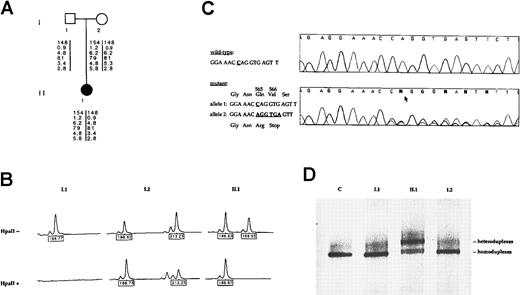

Pedigree, mutation detection, and X chromosome inactivation analysis.

(A) Pedigree of the family and results of the polymorphism analysis with 6 F8 markers. From the top to the bottom: CA repeat ofF8 intron 13, F8 BclI intron 18, CA repeat ofF8 intron 22, XbaI/KpnI F8 intron 22, DXS 52, and DXS 15 mapping 3 recombination units from the F8 gene. (B) X-inactivation analysis at the HUMARA locus. On the top line, results of the PCR amplification of the androgen-receptor polymorphic (CAG) repeat without HpaII digestion. The proband (II.1) is heterozygous at this locus and inherited the allele 186 from her mother and the allele 198 from her father. Her paternally derived allele (198) is completely digested by the methylation-sensitive restriction enzymeHpaII and, therefore, not amplified by PCR. The remaining peak (186) is the maternally derived allele and represents the inactive, methylated X chromosome that resists cleavage byHpaII and thus is successfully amplified. This female patient thus shows complete skewing of X inactivation. (C) Identification of the Q565delC/ter566 mutation in theF8 gene. F8 exon 11 direct nucleotide sequence fragments are shown in an unrelated wild-type control and in the patient with the relevant wild-type and mutant sequences noted to the left. In the mutated allele, a C is deleted (arrow) and results in overriding of the wild-type and mutated sequences 3′ to the deletion point. (D) Exon 11 mutation DGGE screening in the family. Lane 1, migration pattern of the wild-type alleles from a control subject (C). Lane 2 and 4, DNA samples from the proband's mother (I.2) and the proband's father (I.1), respectively, demonstrating a same migration pattern than the control. Lane 3, DGGE profile of the Q565delC/ter566 mutation from the heterozygous female patient (II.1).

Pedigree, mutation detection, and X chromosome inactivation analysis.

(A) Pedigree of the family and results of the polymorphism analysis with 6 F8 markers. From the top to the bottom: CA repeat ofF8 intron 13, F8 BclI intron 18, CA repeat ofF8 intron 22, XbaI/KpnI F8 intron 22, DXS 52, and DXS 15 mapping 3 recombination units from the F8 gene. (B) X-inactivation analysis at the HUMARA locus. On the top line, results of the PCR amplification of the androgen-receptor polymorphic (CAG) repeat without HpaII digestion. The proband (II.1) is heterozygous at this locus and inherited the allele 186 from her mother and the allele 198 from her father. Her paternally derived allele (198) is completely digested by the methylation-sensitive restriction enzymeHpaII and, therefore, not amplified by PCR. The remaining peak (186) is the maternally derived allele and represents the inactive, methylated X chromosome that resists cleavage byHpaII and thus is successfully amplified. This female patient thus shows complete skewing of X inactivation. (C) Identification of the Q565delC/ter566 mutation in theF8 gene. F8 exon 11 direct nucleotide sequence fragments are shown in an unrelated wild-type control and in the patient with the relevant wild-type and mutant sequences noted to the left. In the mutated allele, a C is deleted (arrow) and results in overriding of the wild-type and mutated sequences 3′ to the deletion point. (D) Exon 11 mutation DGGE screening in the family. Lane 1, migration pattern of the wild-type alleles from a control subject (C). Lane 2 and 4, DNA samples from the proband's mother (I.2) and the proband's father (I.1), respectively, demonstrating a same migration pattern than the control. Lane 3, DGGE profile of the Q565delC/ter566 mutation from the heterozygous female patient (II.1).

In this family, both the proband and her mother were informative at the HUMARA locus, as shown in Figure 1B, after PCR amplification of the HUMARA CAG repeat before HpaII digestion. As shown in Figure 1B, 2 distinct alleles were observed in the female proposita (II.1), one allele (186) inherited from her mother and the allele 198 derived from her father. Following HpaII digestion, we observed that only one allele (186) was amplified in the patient II.1, indicating a skewed X inactivation. This allele represents the inactivated X chromosome and corresponds to the maternally derived allele. The patient showed a degree of skewing consistent with the designation of “extremely skewed” with a ratio greater than 95:5.11 X-inactivation analysis of this family demonstrated that the female patient carried only one active paternally derived X chromosome. In conclusion, analysis of methylation at the HUMARA locus from peripheral blood cells suggests that skewed X inactivation is the mechanism underlying hemophilia A in this girl, although the liver, where factor VIII is primarily synthesized, could not be tested.

Because the proband's father was not hemophiliac, it suggests that the mutation in the F8 gene occurred de novo on the paternal active X chromosome of the female patient. A high-resolution karyotype from the proband and her parents did not reveal any chromosomal abnormalities that might explain the pattern of skewed X chromosome inactivation. To identify the F8 gene mutation,BclI Southern blot analysis for the F8 intron 22 inversion, which is commonly found in severe hemophiliacs, was performed in the patient and her parents.2,3 The results showed that the proband and both her parents exhibited a normalBclI pattern, demonstrating the absence of F8gene inversions (data not shown). Therefore, we screened all the coding sequences and exon-intron boundaries of the F8 gene by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis and direct sequencing.6 We characterized by direct sequencing of exon 11 a frameshift-stop mutation in the heterozygous state from the proposita (Figure 1C). This mutation corresponds to a frameshift 1-base pair (bp) deletion that led to a premature termination codon at position 566 (Q565delC/ter566) that is expected to generate an unstable transcript that is degraded. Therefore, this molecular pathology is consistent with a severe hemophilia A phenotype observed in the female proposita. This mutation was detected neither in the proband's father nor in the proband's maternal leukocytes' DNA, suggesting that this mutation probably occurred de novo in the father's germline (Figure1D).

Three mechanisms are currently recognized for an unbalanced pattern of X chromosome inactivation in chromosomally normal females: a stochastic fluctuation in the embryonic progenitor cells, a postinactivation selection of cells bearing a mutation that affects cell survival in a particular tissue, and finally a defect in the X-inactivation process itself affecting the correct expression of the XIST gene or the spreading of the inactivation signal.14For instance, 2 unrelated families have been documented in which females carried a mutation in the XIST promoter that segregated with a skewed X chromosome inactivation.23 Subsequently, we sequenced the minimal XIST promoter region in the female proposita, but no change in the sequence of this region was observed (data not shown).

In conclusion, the severe hemophilia A in this female results from the occurrence of a de novo frameshift-stop mutation in the F8gene on the paternally derived X chromosome, associated with a nonrandom pattern of inactivation of the maternally derived X chromosome. This study further illustrates the value of X chromosome inactivation analysis to explain the phenotypic expression of an X-linked disorder in heterozygous female carriers, such as hemophilia A. Furthermore the report of such clinical cases, which are unusual, are of utmost importance for the understanding of the X chromosome inactivation process in humans.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Marc Delpech, Laboratoire de Biochimie et Génétique Moléculaire, 123 boulevard du Port-Royal, 75014 Paris, France; e-mail: delpech@icgm.cochin.inserm.fr.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal