Abstract

Elevated plasma levels of factor VIII (> 150 IU/dL) are an important risk factor for deep vein thrombosis (DVT). Factor VIII is the cofactor of factor IXa in the activation of factor X. The risk of thrombosis in individuals with an elevated factor IX level is unknown. This study investigated the role of elevated factor IX levels in the development of DVT. We compared 426 patients with a first objectively diagnosed episode of DVT with 473 population controls. This study was part of a large population-based case-control study on risk factors for venous thrombosis, the Leiden Thrombophilia Study (LETS). Using the 90th percentile measured in control subjects (P90 = 129 U/dL) as a cutoff point for factor IX levels, we found a 2- to 3-fold increased risk for individuals who have factor IX levels above 129 U/dL compared with individuals having factor IX levels below this cutoff point. This risk was not affected by adjustment for possible confounders (age, sex, oral contraceptive use, and high levels of factor VIII, XI, and vitamin K-dependent proteins). After exclusion of individuals with known genetic disorders, we still found an odds ratio (OR) of 2.5 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.6-3.9). The risk was higher in women (OR: 2.6, CI: 1.6-4.3) than in men (OR: 1.9, CI: 1.0-3.6) and appeared highest in the group of premenopausal women not using oral contraceptives (OR: 12.4, CI: 3.3-47.2). These results show that an elevated level of factor IX is a common risk factor for DVT.

The incidence of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in the general population is about 1 in 1000 people per year.1,2The pathogenesis of DVT is complex. In theory, hyperactive coagulation pathways, hypoactive anticoagulant mechanisms, or hypoactive fibrinolysis may cause the development of DVT.3

Risk factors can be classified into acquired and genetic factors.4 DVT is a multicausal disease; that is, more than a single risk factor needs to be present simultaneously to cause thrombosis.5,6 Known acquired risk factors include immobilization, surgery, trauma, pregnancy, puerperium, lupus anticoagulant, malignant disease, and female hormones.5,7Genetic risk factors causing a tendency to DVT are antithrombin deficiency,8 protein C deficiency,9 protein S deficiency,10 the factor V Leiden mutation,11and the prothrombin 20210 A allele.12 However, in about 30% of patients with a family history of DVT, no underlying genetic defect will be found. 13

Other risk factors that are frequently reported among patients with DVT are elevated factor VIII levels14 and hyperhomocysteinemia.15,16 We recently found that elevated levels of factor XI17 and factor X in women who do not use oral contraceptives18 are also associated with the risk of thrombosis. The molecular basis of these abnormalities is still unknown. Because factor VIII is the cofactor of factor IXa in the activation of factor X, it seemed plausible that elevated levels of factor IX could also be a risk factor for DVT.

Factor IX plays a key role in hemostasis; it is a vitamin K–dependent glycoprotein, which is activated through the intrinsic pathway as well as the extrinsic pathway.19 Factor IX, when activated by factor XIa or factor VIIa-tissue factor, converts factor X into Xa and this eventually leads to the formation of a fibrin clot. This conversion is accelerated by the presence of the nonenzymatic cofactor factor VIIIa, calcium ions, and a phospholipid membrane.20In healthy individuals, factor IX activity and antigen levels vary between 50% and 150% of that in pooled normal plasma.21Several studies have reported that factor IX levels increase with age22-24 as well as with oral contraceptive use.23 25 Deficiencies of factor VIII (hemophilia A) and factor IX (hemophilia B) lead to clinically identical bleeding tendencies. Analogy suggests similar effects of high levels of both clotting factors on thrombotic risk.

In this study, we investigated the role of elevated coagulation factor IX levels in the development of a first DVT. The study was part of a large population-based case-control study on risk factors of venous thrombosis, the Leiden Thrombophilia Study (LETS).

Patients, materials, and methods

Study design

The design of this study has been described in detail previously.26 27 In short, we included 474 consecutive patients younger than 70 years with an objectively confirmed first episode of DVT that occurred in the period between January 1988 and December 1992, who were selected from the files of the anticoagulation clinics in Leiden, Amsterdam, and Rotterdam. These clinics monitor outpatient anticoagulant treatment in well-defined geographical areas. Patients with known malignant disorders were excluded. Each thrombosis patient was asked to find his or her own control subject with the same sex and approximately the same age (within 5 years). Partners of patients were also asked if they were willing to participate in this study as a control subject; if a patient was unable to find a control subject, the first individual on the list of partners matching for sex and age was asked to join the study; 474 control subjects were included. Blood was collected from the antecubital vein into Starstedt Monovette tubes, in 0.1 volume 0.106 mol/L trisodium citrate. Plasma was prepared by centrifugation for 10 minutes at 2000g at room temperature and stored at −70°C, until used. Patients and controls were seen concurrently and all samples were analyzed with the same batch of reagents, using the same pooled normal plasma within a 6-week period.

Forty-eight of the patients and 1 of the control subjects were on long-term oral anticoagulant therapy and, because this results in reduced levels of the vitamin K–dependent proteins, they were excluded from the analysis. For the current analysis, we therefore studied 426 patients and 473 control subjects. The median time between thrombosis and venipuncture for this study was 18 months (range, 6-56 months).

Measurement of factor IX

The levels of factor IX were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). This ELISA is highly specific for factor IX and results are not affected by the levels of the other vitamin K–dependent proteins. PVC-microtiter plates (ICN Biomedicals BV, Zoetermeer, The Netherlands) were coated with rabbit antifactor IX antibodies as capture antibodies (DAKO A/S, Glostrup, Denmark; 3 μg/mL, 100 μL/well). Bound factor IX was detected with non-Ca++-dependent antifactor IX IgG28conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP). HRP activity was measured with o-phenylenediamine. The color reaction was stopped after 15 minutes using H2SO4 and read spectrophotometrically at 492 nm. The assay was calibrated with dilutions of pooled normal plasma (1:25-1:1600). Plasmas were diluted in washing buffer (50 mmol/L triethanolamine, pH 7.5, 100 mmol/L NaCl, 10 mmol/L EDTA, 0.1% Tween). The factor IX content of a plasma sample was calculated as the mean result of single determinations of 3 different dilutions (1:100, 1:200, and 1:400). Results were accepted when the coefficient of variation (CV) was less than 10%. Under these conditions, the intra-assay and interassay CV was 7% (n = 9) and 7.2% (n = 41), respectively, at a factor IX antigen level of about 100 U/dL. Results are expressed in units per deciliter, where 1 U is the amount of factor IX present in 1 mL pooled normal plasma.

Because of the presence of EDTA in the buffer, only antibodies against the non-Ca++-dependent conformation of factor IX are used. Therefore results will not be influenced by variations in the degree of γ-carboxylation of factor IX and represent truly factor IX protein concentrations in plasma. Identical results can be obtained by using commercial antifactor IX-HRP (Enzyme Research Laboratories, South Bend, IN) or commercial factor IX ELISA, provided that EDTA is present in or added to the buffer system.

Factor VII and VIII were measured by 1-stage coagulation assays.14,29 Prothrombin levels were measured by a chromogenic assay using Echis carinatus venom as activator.12 Factor X antigen was measured by a sandwich ELISA using commercial polyclonal antibodies (DAKO A/S)18and factor XI antigen by an ELISA using a monoclonal antifactor XI antibody as catching antibody and polyclonal antifactor XI as tagging antibody.17

The technician was blinded concerning the origin of the sample, that is, whether it was from a patient or from a control subject.

Statistical analysis

The study was divided into 2 parts. First we investigated possible determinants of factor IX levels, looking only at the control subjects as reflecting the general population. The determinants were established mainly by comparing means and using linear regression. To assess the relationship between factor IX levels and oral contraceptive use, an extra selection was made in the study population, as described earlier.30 31 We selected nonmenopausal women between 15 and 49 years of age. Women who were at the index date (similar date as time of thrombosis for patients) pregnant (n = 10), within 30 days postpartum (n = 14), who had a recent miscarriage (n = 2), or had used only depot contraceptives (n = 3) were excluded. A total of 153 control subjects were left for this specific analysis.

Secondly, we investigated whether a high level of factor IX is a risk factor for DVT by calculating the adds ratio (OR) and the 95% confidence interval (CI). As a cutoff point we used the 90th percentile of factor IX levels measured in the control subjects. The factor IX levels were also divided in strata to assess a relationship between factor IX levels and the thrombosis risk (dose response).

To adjust for possible confounders, for example, age, sex, oral contraceptive use at the time of thrombosis as well as at the time of venipuncture, and high levels of factor VIII, XI, and the vitamin K–dependent clotting factors (all dichotomized at the 90th percentile), we used a logistic regression model. In case of sparse data (ie, known genetic risk factors for thrombosis, oral contraceptive use), we also used restriction, that is, analysis only of those without thrombophilic risk factors, only of men, or only of women (premenopausal and postmenopausal) who did not change their oral contraceptive use since their thrombosis (and who were not pregnant, not within 30 days postpartum, did not have a recent miscarriage, nor used only depot oral contraceptives). The thrombophilic risk factors used in the restriction were protein C deficiency (< 0.67 U/mL), protein S deficiency (< 0.67 U/mL), antithrombin deficiency (< 0.80 U/mL), the factor V Leiden mutation, and the prothrombin 20210 A allele.32

Because factor VIII is the cofactor of factor IX and itself a risk factor for thrombosis,14 we assessed the effect on the thrombotic risk of elevated factor IX levels alone and of elevated factor IX levels in combination with elevated factor VIII levels.

Results

The mean age of patients and controls at the time of the thrombosis was 45 years (range, patients 15-69; controls, 15-72). Among cases and controls alike, 59% were women.

Determinants of factor IX levels

The mean (range) of factor IX levels was 103 (52-188) U/dL. As shown in Table 1, factor IX levels increased with age, only after the age of 55; factor IX levels were almost equal in men and in women (mean difference: 3.4 U/dL, CI: −0.4 to 7.2). No difference was found in factor IX levels between blood groups. Factor IX levels were weakly associated with factor VIII and factor XI levels (regression coefficient with factor IX level as dependent variable, factor VIII: 0.18, CI: 0.12-0.24 and factor XI 0.23, CI: 0.14-0.33).

Factor IX levels (U/dL) in healthy control subjects

| . | n (473) . | Factor IX mean (SD) . |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Men | 201 | 105 (19.5) |

| Women | 272 | 102 (21.9) |

| Use of oral contraceptives* | ||

| Yes | 54 | 115 (23.4) |

| No | 99 | 93 (18.8) |

| Age (y) | ||

| ≤ 35 | 118 | 100 (20.6) |

| 35-45 | 118 | 102 (21.2) |

| 45-55 | 119 | 100 (18.9) |

| ≥ 55 | 118 | 110 (21.5) |

| . | n (473) . | Factor IX mean (SD) . |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Men | 201 | 105 (19.5) |

| Women | 272 | 102 (21.9) |

| Use of oral contraceptives* | ||

| Yes | 54 | 115 (23.4) |

| No | 99 | 93 (18.8) |

| Age (y) | ||

| ≤ 35 | 118 | 100 (20.6) |

| 35-45 | 118 | 102 (21.2) |

| 45-55 | 119 | 100 (18.9) |

| ≥ 55 | 118 | 110 (21.5) |

At time of venipuncture, for 153 women in reproductive age (see “Materials and methods” for selection criteria).

Among 153 healthy premenopausal women, factor IX levels were substantially higher among women who used oral contraceptives compared with women who did not (mean difference: 22.7 U/dL, CI: 15.8-29.5, after age adjustment: 25.6 U/dL, CI: 18.0-33.2).

The time between thrombosis and the venipuncture did not influence the levels of factor IX in the patients. After dividing the intervening time into 4 periods, the factor IX levels remained approximately the same, ranging from 113 U/dL in individuals with a venipuncture within 1 year after the thrombosis (n = 108) to 111 U/dL in individuals with a venipuncture more than 3 years after their thrombosis (n = 35).

Factor IX as a risk factor for DVT

Ten percent of the healthy control subjects had factor IX levels above 129 U/dL (90th percentile = 129 U/dL). More than 20% of the patients had factor IX levels exceeding this cutoff point, which implies that individuals with a factor IX level higher than 129 U/dL had a more than 2-fold increased risk to develop DVT when compared with individuals having factor IX levels below this cutoff value (Table2). After adjustment for age, sex, and oral contraceptive use, the OR was 2.8 (CI: 1.9-4.3). When adjustment included factor VIII, XI, and vitamin K–dependent clotting factor levels (all dichotomized at the 90th percentile), the OR was 2.0 (CI: 1.3-3.2). When adjustment only included the vitamin K–dependent clotting factors (factor II, VII, and X), the risk associated with factor IX levels exceeding the 90th percentile remained increased 2-fold (OR: 2.0; CI: 1.3- 3.0). Additional adjustment for C-reactive protein did not affect the risk estimates.

Crude odds ratios for subgroups

| . | Above 90th percentile (> 129 U/dL) . | Below 90th percentile (≤ 129 U/dL) . | Odds ratio (95% CI) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 899) | |||

| Patients | 86 | 340 | 2.3 (1.6-3.5) |

| Controls | 46 | 427 | |

| Sex | |||

| Men (n = 373) | |||

| Patients | 29 | 143 | 1.9 (1.0-3.6) |

| Controls | 19 | 182 | |

| Women (all) (n = 526) | |||

| Patients | 57 | 197 | 2.6 (1.6-4.3) |

| Controls | 27 | 245 | |

| Use of oral contraceptives* | |||

| Yes (premenopausal) (n = 77) | |||

| Patients | 10 | 20 | 1.5 (0.5-4.0) |

| Controls | 12 | 35 | |

| No (premenopausal) (n = 130) | |||

| Patients | 12 | 28 | 12.4 (3.3-47.2) |

| Controls | 3 | 87 | |

| No (postmenopausal) (n = 148) | |||

| Patients | 21 | 39 | 6.2 (2.4-15.9) |

| Controls | 7 | 81 | |

| Age (y) | |||

| < 45 (n = 453) | |||

| Patients | 37 | 180 | 2.5 (1.4-4.5) |

| Controls | 18 | 218 | |

| ≥ 45 (n = 446) | |||

| Patients | 49 | 160 | 2.3 (1.4-3.8) |

| Controls | 28 | 209 |

| . | Above 90th percentile (> 129 U/dL) . | Below 90th percentile (≤ 129 U/dL) . | Odds ratio (95% CI) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 899) | |||

| Patients | 86 | 340 | 2.3 (1.6-3.5) |

| Controls | 46 | 427 | |

| Sex | |||

| Men (n = 373) | |||

| Patients | 29 | 143 | 1.9 (1.0-3.6) |

| Controls | 19 | 182 | |

| Women (all) (n = 526) | |||

| Patients | 57 | 197 | 2.6 (1.6-4.3) |

| Controls | 27 | 245 | |

| Use of oral contraceptives* | |||

| Yes (premenopausal) (n = 77) | |||

| Patients | 10 | 20 | 1.5 (0.5-4.0) |

| Controls | 12 | 35 | |

| No (premenopausal) (n = 130) | |||

| Patients | 12 | 28 | 12.4 (3.3-47.2) |

| Controls | 3 | 87 | |

| No (postmenopausal) (n = 148) | |||

| Patients | 21 | 39 | 6.2 (2.4-15.9) |

| Controls | 7 | 81 | |

| Age (y) | |||

| < 45 (n = 453) | |||

| Patients | 37 | 180 | 2.5 (1.4-4.5) |

| Controls | 18 | 218 | |

| ≥ 45 (n = 446) | |||

| Patients | 49 | 160 | 2.3 (1.4-3.8) |

| Controls | 28 | 209 |

At time of thrombosis (or similar index date for controls) as well as at time of venipuncture (16 of the 153 premenopausal women mentioned earlier changed their oral contraceptive use and were therefore excluded from this analysis).

A total of 130 patients and 51 control subjects had a known genetic risk factor for thrombosis. Exclusion of these individuals only marginally affected the risk estimates (crude OR: 2.5, CI: 1.6-3.9; after adjustment for age, sex, and oral contraceptive use: OR: 3.0, CI: 1.9-4.7; when adjustment included factor VIII, XI, and vitamin K–dependent clotting factor levels: OR: 2.2, CI: 1.3-3.6).

We used the 90th percentile as a cutoff point for the levels of factor IX. When the 95th percentile (P95 = 142 U/dL) was used, the crude OR was slightly higher, at 2.5 (CI: 1.5-4.3). Table3 shows the risk of thrombosis for strata of factor IX levels. Table 3 shows that there is a relationship between thrombosis and factor IX levels (dose response), with a 3.2-fold increased risk for individuals with factor IX levels over 150 U/dL compared with those having levels below 100 U/dL.

Thrombosis risk for strata of factor IX levels (in U/dL)

| . | Patients . | Controls . | OR (95% CI) . | Adjusted OR3-151 (95% CI) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤ 100 | 167 | 236 | 13-150 | 13-150 |

| 100-125 | 156 | 175 | 1.3 (0.9-1.7) | 1.3 (1.0-1.8) |

| 125-150 | 71 | 48 | 2.1 (1.4-3.2) | 2.7 (1.7-4.2) |

| > 150 | 32 | 14 | 3.2 (1.7-6.2) | 4.8 (2.3-10.1) |

| . | Patients . | Controls . | OR (95% CI) . | Adjusted OR3-151 (95% CI) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤ 100 | 167 | 236 | 13-150 | 13-150 |

| 100-125 | 156 | 175 | 1.3 (0.9-1.7) | 1.3 (1.0-1.8) |

| 125-150 | 71 | 48 | 2.1 (1.4-3.2) | 2.7 (1.7-4.2) |

| > 150 | 32 | 14 | 3.2 (1.7-6.2) | 4.8 (2.3-10.1) |

Reference category.

Odds ratio (OR) adjusted for sex, age, and oral contraceptive use at the time of thrombosis as well as at the time of the venipuncture.

Comparing younger and older subgroups (with the median age as a division), the odds ratios were equal: a 2.5-fold increased risk for high factor IX levels in the individuals aged under 45 and a 2.3-fold increased risk for the older people (Table 2).

When the risk of developing DVT is assessed for men and women separately, as shown in Table 2, we found a slightly higher relative risk in women than in men. Restricting the female population to premenopausal women who did not use oral contraception at the time of thrombosis (or similar date for the controls) nor at the time of venipuncture, the relative risk increased to 12.4. For women using oral contraceptives both at the thrombotic event and at the time of venipuncture, the relative risk was 1.5, whereas for postmenopausal women the relative risk was 6.2.

For the analysis of the effect on the thrombotic risk of combinations of factor VIII and factor IX levels, we used the 90th percentile (of the controls) as cutoff points for both (151 IU/dL for factor VIII and 129 U/dL for factor IX) (Table 4). Although a high level of factor VIII and a high level of factor IX each contribute to the risk of developing DVT, the risk is highest when both clotting factor levels are above the 90th percentile (8 times higher than when both clotting factor levels are below the 90th percentile, CI: 3.6-18.4).

Comparison of the levels of factor IX and factor VIII

| Factor VIII . | Factor IX . | Patients . | Controls . | OR (95% CI) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Low | 278 | 387 | 14-150 |

| High | Low | 62 | 40 | 2.2 (1.4-3.3) |

| Low | High | 45 | 39 | 1.6 (1.0-2.5) |

| High | High | 41 | 7 | 8.2 (3.6-18.4) |

| Factor VIII . | Factor IX . | Patients . | Controls . | OR (95% CI) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Low | 278 | 387 | 14-150 |

| High | Low | 62 | 40 | 2.2 (1.4-3.3) |

| Low | High | 45 | 39 | 1.6 (1.0-2.5) |

| High | High | 41 | 7 | 8.2 (3.6-18.4) |

High means above 90th percentile, low means below 90th percentile (of the control subjects).

The 90th percentile of factor IX and factor VIII, respectively, (measured in control subjects): 129 U/dL and 151 IU/dL.

Reference category.

Discussion

Individuals who have high levels of factor IX (> 129 U/dL) have a more than 2-fold increased risk of developing a first DVT compared with individuals having low levels of factor IX. The risk of thrombosis increased with increasing plasma levels of factor IX (dose response). At factor IX levels more than 125 U/dL, an increase of the risk can already be observed compared with the reference category (factor IX levels ≤ 100 U/dL). Individuals with a factor IX level over 150 U/dL have a more than 3-fold increase in the risk of thrombosis when compared with the reference category.

Deep vein thrombosis is more often seen in women than in men.33 Blood groups other than O, as well as increasing age, increase the risk of developing DVT, which was reviewed in several studies.14,26,33 Our observations that factor IX levels increase with age and with oral contraceptive use are in accordance with earlier studies.23-25 However, the OR for high levels of factor IX adjusted for these factors did not differ from the crude OR, which means that the risk associated with high levels of factor IX is not explained by these other factors nor by other thrombophilic abnormalities, as shown by restriction to individuals without these abnormalities.

It is not likely that the factor IX levels changed as a consequence of the thrombosis because factor IX is not an acute-phase reactant; venipuncture was at least 6 months after the event, and no effect of the time elapsed between thrombosis and venipuncture on factor IX levels was observed; also, adjustment for C-reactive protein did not affect the results.

Age had no effect on the relative risk of DVT caused by elevated levels of factor IX, which implies a larger absolute effect in older age groups where thrombosis is more common than among younger individuals.

The relative risk appeared highest in postmenopausal women (6-fold increased risk) and premenopausal women who did not use oral contraceptives (12-fold increased risk). This high relative risk in women not using oral contraceptives contrasts to previous findings on other abnormalities of the clotting system, where the risk was highest in women who used oral contraceptives.30 For example, the factor V Leiden mutation causes a 7- to 8-fold increase of the risk among both nonusers of oral contraceptives and women who do use oral contraceptives. Because use of oral contraceptives increases the risk 4-fold, the risk in carriers of factor V Leiden mutation who used oral contraceptives was about 30 times higher than the risk in a nonuser who did not carry the mutation.30

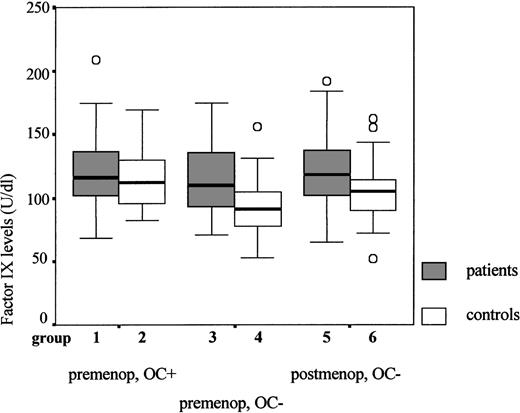

In this study we found, however, that the risk associated with elevated factor IX levels was highest in women who did not use oral contraceptives. An explanation for this finding could be a ceiling value for the factor IX levels; that is, in women who have a tendency to increased factor IX levels, oral contraceptives do not cause additional increases. This is explained in Figure1. Comparing the healthy premenopausal control women in Figure 1 (groups 2 and 4), one can see that oral contraceptive use causes the factor IX levels to rise. Figure 1 also shows that the factor IX levels in premenopausal patients (groups 1 and 3) are about equal, regardless of their oral contraceptive use. In female patients the factor IX levels, therefore, do not seem to increase when they use oral contraceptives, whereas they do increase in healthy female controls. In the group of women who use oral contraceptives (groups 1 and 2), the factor IX levels of patients and controls are therefore closer together, which decreases the estimated relative risk.

Comparison of the factor IX levels in premenopausal and postmenopausal women.

Factor IX antigen levels are shown (median, interquartile range, and range); OC+ refers to oral contraceptive use both at the time of thrombosis and at the time of venipuncture; OC− refers to nonusers of oral contraceptives (both at the time of thrombosis and at the time of the venipuncture); premenop and postmenop refer to premenopausal and postmenopausal, respectively. Group 1: premenopausal patients using oral contraceptives (n = 30; median = 116 U/dL); group 2: premenopausal healthy controls using oral contraceptives (n = 47; median = 112 U/dL); group 3: premenopausal patients not using oral contraceptives (n = 40; median = 110 U/dL); group 4: premenopausal healthy controls not using oral contraceptives (n = 90; median = 91 U/dL); group 5: postmenopausal patients not using oral contraceptives (n = 60; median = 119 U/dL); group 6: postmenopausal controls not using oral contraceptives (n = 88; median = 105 U/dL).

Comparison of the factor IX levels in premenopausal and postmenopausal women.

Factor IX antigen levels are shown (median, interquartile range, and range); OC+ refers to oral contraceptive use both at the time of thrombosis and at the time of venipuncture; OC− refers to nonusers of oral contraceptives (both at the time of thrombosis and at the time of the venipuncture); premenop and postmenop refer to premenopausal and postmenopausal, respectively. Group 1: premenopausal patients using oral contraceptives (n = 30; median = 116 U/dL); group 2: premenopausal healthy controls using oral contraceptives (n = 47; median = 112 U/dL); group 3: premenopausal patients not using oral contraceptives (n = 40; median = 110 U/dL); group 4: premenopausal healthy controls not using oral contraceptives (n = 90; median = 91 U/dL); group 5: postmenopausal patients not using oral contraceptives (n = 60; median = 119 U/dL); group 6: postmenopausal controls not using oral contraceptives (n = 88; median = 105 U/dL).

This does not mean that oral contraceptives act protectively against the risk of DVT due to elevated levels of factor IX. It may be, however, that in women who already have elevated levels of factor IX, the use of oral contraceptives does not contribute further to the risk of DVT associated with increased levels of factor IX. Another explanation is chance. Compared with women who did not use oral contraceptives and had low factor IX levels, those who had high factor IX levels and did not use oral contraceptives had a 12-fold increased risk after age adjustment (CI: 3.1-45.5), whereas those who used oral contraceptives and had high factor IX levels had a 3.3-fold increased risk (CI: 1.2-8.9). The confidence intervals of those estimates show a fairly large overlap.

The results of this study indicate that an elevated level of factor IX is a common risk factor for DVT. The relative risk of thrombosis of 2.3 caused by high levels of factor IX (> 129 U/dL) is present in 10% of the population. This implies that high levels of factor IX are responsible for a considerable number of thromboses.

The development of DVT is the result of several interactions between genetic and environmental components.5,6 The role of factor VIII as a risk factor of DVT was described earlier.14 We found that both factor VIII and factor IX levels contribute to the risk of DVT. When both coagulation factors are elevated, however, the risk of DVT is highest. At present, the molecular basis of elevated factor IX levels is unknown (genetic, acquired, or a combination of both). More studies need to be done to find out what causes factor IX levels to be high or low.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr F. J. M. van der Meer (Anticoagulation Clinic, Leiden), Dr L. P. Colly (Anticoagulation Clinic, Amsterdam), and Dr P. H. Trienekens (Anticoagulation Clinic, Rotterdam) for their kind cooperation and Dr T. Koster for collecting blood samples from patients and control subjects.

Supported by the Netherlands Heart Foundation (number 89.063).

Correspondence:F. R. Rosendaal, Department of Clinical Epidemiology, Leiden University Medical Center, C0-P46, PO Box 9600, NL-2300 RC, Leiden, The Netherlands; e-mail:f.r.rosendaal@lumc.nl.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal