Abstract

FKLF-2, a novel Krüppel-type zinc finger protein, was cloned from murine yolk sac. The deduced polypeptide sequence of 289 amino acids has 3 contiguous zinc fingers at the near carboxyl-terminal end, an amino-terminal domain characterized by its high content of alanine and proline residues and a carboxyl-terminal domain rich in serine residues. By Northern blot hybridization, the human homologue of FKLF-2 is expressed in the bone marrow and striated muscles and not in 12 other human tissues analyzed. FKLF-2 is constitutively expressed in established cell lines with an erythroid phenotype, but it is inconsistently expressed in cell lines with myeloid or lymphoid phenotypes. The expression of FKLF-2 messenger RNA (mRNA) is up-regulated after induction of mouse erythroleukemia cells. In luciferase assays, FKLF-2 activates predominantly the γ, and to a lesser degree, the ɛ and β globin gene promoters. The activation of γ gene promoter does not depend on the presence of an HS2 enhancer. FKLF-2 activates the γ promoter predominantly by interacting with the γ CACCC box, and to a lesser degree through interaction with the TATA box or its surrounding DNA sequences. FKLF-2 also activated all the other erythroid specific promoters we tested (GATA-1, glycophorin B, ferrochelatase, porphobilinogen deaminase, and 5-aminolevulinate synthase). These results suggest that in addition to globin, FKLF-2 may be involved in activation of transcription of a wide range of genes in the cells of the erythroid lineage.

There has been a considerable effort to identify transcriptional factors that provide developmental specificity in globin gene expression. The first such factor to be identified was EKLF.1 This is a member of the KLF/Sp1 family of transcriptional factors and it is characterized by specificity of expression in the erythroid lineage and its interaction with the CACCC box of the β globin gene promoter. There are considerable differences in the sequence of CACCC boxes of the β and γ gene promoters2 and there is clear-cut evidence that EKLF fails to activate the γ promoter.3 EKLF-deficient homozygous mice die from severe anemia due to β globin chain deficiency when the definitive erythropoiesis is established in the fetal liver.4,5 When a human γ transgene is transferred into the background of the EKLF-deficient animals, human γ gene transcription is increased, providing direct in vivo evidence that EKLF does not interact with the γ gene promoter.6 7

It is reasonable to assume that, on the model of EKLF, transcriptional factors that can activate the embryonic ε or the fetal γ globin genes exist. Because the ε and γ genes have CACCC box motifs in their promoters, it is also reasonable to assume that transcriptional factors of the KLF/Sp1 family may participate in the developmental control of these genes. We have previously described the cloning and characterization of a factor, designated as FKLF,8 that activates the expression predominantly of the ε, and to a lesser degree, of the γ globin genes. We have shown that γ gene expression is activated through the interaction of FKLF with the γ gene CACCC box and that this transcriptional factor fails to activate other erythroid genes that contain CACCC or GC motifs.8 In this paper, we describe the cloning and characterization of a new transcriptional factor belonging to theKLF/Sp1 family, which we designate as FKLF-2. This factor increases γ gene expression more than 100-fold in transient expression assays. FKLF-2 is not a specific activator of the γ gene expression because it activates to a lesser extent the ε and the β globin genes. This transcriptional factor also activated all other erythroid genes we used in our assays, although to a much lower degree, compared with the γ globin gene.

Materials and methods

Induction of erythroid cells and RNA extractions

Cells were induced as follows: K562 with 50 μmol/L hemin for 3 days; MEL with 3 mmol/L N, N′-hexamethylenebisacetamide (HMBA) and 10 μmol/L hemin for 3 days; and HEL with 500 μmol/L δ-aminolevulinic acid (δ-ALA) for 5 days. Total RNA extraction and processing are described elsewhere.8

Polymerase chain reaction screening for zinc finger motifs

Screening of mouse yolk sac cell cDNA for zinc finger motifs was performed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) essentially as described previously.8 Random hexamer-primed cDNA of 1 μg of poly(A)+RNA from day-10 mouse yolk sac cells was subjected to degenerate primer PCR. The expected 210 base pairs (bp) band was cut out, and the extracted DNA was ligated into a plasmid vector (T vector, Promega, Madison, WI). Plasmid DNA was analyzed by restriction enzyme digestion, and clones containing an insert were subjected to PCR to exclude EKLF clones. Clones that were not excluded were sequenced using a kit (Cyclist; Stratagene, La Jolla, CA).

Complementary DNA cloning

The 3′ and 5′ unknown complementary DNA (cDNA) sequences were amplified by the RACE (rapid amplification of cDNA ends)-PCR using a kit (Marathon cDNA amplification kit; Clontech, Palo Alto, CA), and a cDNA sequence composed of 1378 bp nucleotides was determined. On the basis of this sequence, a 917 bp open reading frame (ORF) predicted to encode the FKLF-2 protein was amplified from random hexamer-primed cDNA using Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene). The PCR fragment was inserted into T-vector after dA addition to the 3′ ends of the PCR fragment, according to the manufacturer's instruction. A clone (pGEM/FKLF-2) without mutation was used for further plasmid construction.

Plasmid constructions

Transactivator plasmid of FKLF-2 was prepared as follows: FKLF-2 cDNA was cut out as a blunted SpeI-NcoI fragment from the pGEM/FKLF-2 and was inserted into the pSG5DD vector at blunted EcoRI andBamHI sites (pSG5/FKLF-2).

Reporter plasmids, pHS2βLuc and pHS2γLuc, pHS2εLuc and pγLuc, and pHS2γ(ΔCAC)Luc were already described elsewhere.8pγ(ΔCAC)Luc, in which a 9-bp CACCC sequence was deleted from the γ promoter, was constructed by insertion ofApaI-HindIII fragment of pHS2γ(ΔCAC)Luc intoApaI- and HindIII-digested pγLuc. Stage selector element (SSE)9 was deleted from pγLuc and pγ(ΔCAC)Luc by in vitro mutagenesis (Altered Sites II in vitro Mutagenesis Systems, Promega). KpnI-HindIII fragments of pγLuc and pγ(ΔCAC)Luc were subcloned into KpnI- andHindIII-digested pALTER-1 vector (Promega). The SSE was deleted using a 5′ phosphorylated oligonucleotide; 5′-pTGAGGCCAGGGGCCAAGAA- TAAAAGGAAGCA-3′, which lacks nucleotides −35 to −52 relative to the cap site of γ gene. Constructs generated by in vitro mutagenesis were verified by sequencing. Reporter constructs with truncated γ promoters were constructed by inserting ApaI (blunted)-HindIII,NcoI (blunted)-HindIII, EcoNI (blunted)-HindIII, and NaeI-HindIII fragments from pγLuc into KpnI (blunted)/HindIII sites of the pGL2-Basic vector (Promega), resulting in pγ−201Luc, pγ−141Luc, pγ−103Luc, and pγ−52Luc, respectively.

DNA of promoters of GATA-1, porphobilinogen deaminase (PBGD), glycophorin B (GPB), ferrochelatase (FC), and 5-aminolevulinate synthase (ALAS) were obtained from pHS2-GATA-Luc, pHS2-PBGD-Luc, pHS2-GPB-Luc, pHS2-FC-Luc, and pHS2-ALAS-Luc8 asBglII fragments (GATA, PBGD, GPB, and FC) orBglII-PvuII fragment (ALAS). Subsequently, they were inserted into a BglII site or BglII/HindIII (blunted) sites of pGL2Basic vector, resulting in pGATA-Luc, pPBGD-Luc, pGPB-Luc, pFC-Luc, and pALAS-Luc.

Transactivation analysis, Northern blotting, and messenger RNA detection by polymerase chain reaction

Transient transfections of K562 cells, Northern blottings, and semiquantitative reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) to study gene expression were performed as described previously.8 Primer information and PCR conditions used in this study will be provided on request.

Results

Cloning of FKLF-2 complementary DNA

For cloning cDNAs encoding EKLF- or Sp1-type zinc finger proteins by PCR, a set of degenerate primers was designed on the basis of the amino acid homology of the zinc finger region of Sp1 and EKLF family proteins. The upstream primer corresponded to the conserved amino acid sequence GCGKVY, whereas the downstream primer to the conserved sequence F(SM)RSDEL (Figure 1A). One hundred eighty-nine individual clones were isolated from a day-10 mouse yolk sac cDNA and sequenced. One hundred six clones encoded Cys2-His2 type zinc finger motifs: 69 encoded EKLF; 31 encoded BKLF;10 2 encoded the murine equivalent of Sp311,12; 1 encoded the murine equivalent of CPBP/Zf913,14; 2 encoded the murine equivalent of UKLF15 ;and 1 encoded a novel cDNA. The human homologue of this novel cDNA was also cloned from human fetal liver erythroid cells using a similar method. On the basis of its structural similarity to the previously described FKLF,8 the novel gene was designated as FKLF-2.

FKLF-2.

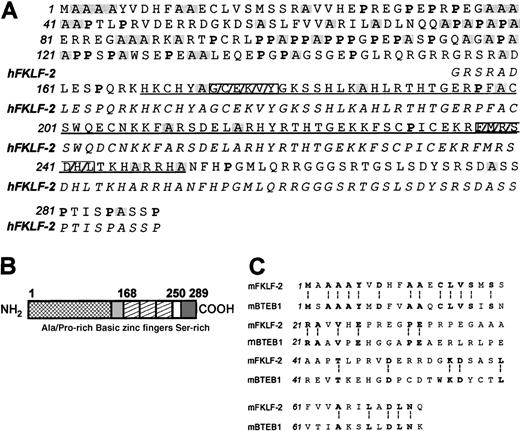

(A) Deduced polypeptide sequence of murine FKLF-2 (mFKLF-2, Genebank accession number: AF251796). Proline residues are shown with a bold typeface, and alanine residues are highlighted with a shaded box. The sequence of the 3 zinc fingers is underlined, and the conserved polypeptide regions used for the preparation of degenerate primers are indicated by boxes with gray stripes. Polypeptide sequence of human FKLF-2 (hFKLF-2) is also shown with an italic typeface below the equivalent mFKLF-2 sequence. (B) Schematic representation of structure of deduced FKLF-2 protein. Alanine and proline-rich in serine residues are shown by shaded boxes. Three zinc fingers are shown by striped boxes. Numbers above the boxes represent amino acid positions from the first methionine. (C) Comparison of amino-terminal polypeptide sequences between mFKLF-2 and mBTEB1.22 Identical amino acid residues are shown by a bold typeface and marked with a symbol (:).

FKLF-2.

(A) Deduced polypeptide sequence of murine FKLF-2 (mFKLF-2, Genebank accession number: AF251796). Proline residues are shown with a bold typeface, and alanine residues are highlighted with a shaded box. The sequence of the 3 zinc fingers is underlined, and the conserved polypeptide regions used for the preparation of degenerate primers are indicated by boxes with gray stripes. Polypeptide sequence of human FKLF-2 (hFKLF-2) is also shown with an italic typeface below the equivalent mFKLF-2 sequence. (B) Schematic representation of structure of deduced FKLF-2 protein. Alanine and proline-rich in serine residues are shown by shaded boxes. Three zinc fingers are shown by striped boxes. Numbers above the boxes represent amino acid positions from the first methionine. (C) Comparison of amino-terminal polypeptide sequences between mFKLF-2 and mBTEB1.22 Identical amino acid residues are shown by a bold typeface and marked with a symbol (:).

The 1378-bp cDNA of murine FKLF-2 includes an ORF that encodes 289 amino acids with a 31.1 kd molecular mass (Figure 1A). The deduced polypeptide sequence of the human FKLF-2 is also shown in Figure 1A. The human and murine sequences differ by a single amino acid change (glutamic acid at 204 of mFKLF-2 → aspartic acid).

FKLF-2: a new Krüppel-type zinc finger protein of the FKLF/TIEG family

The deduced polypeptide sequence of the FKLF-2 contains a zinc finger domain composed of 3 contiguous fingers present near the carboxyl-terminal end, a long amino-terminal domain, and a short carboxyl-terminal domain (Figure 1A and 1B). The structure of the zinc finger (C-X4-C-X12-H-X3-H-X7-C-X4-C-12-H-X3-H-X7-C-X2-C-X12-H-X3-H, where X represents any amino acid residue), is similar to that of Sp1, EKLF, and other proteins of their families.12,16,17 The zinc finger motif of FKLF-2 has an intermediate homology to the proteins of both the Sp1 family (Sp1, Sp2,12 Sp3, and Sp411) and the proteins of the EKLF family (EKLF, BTEB2/IKLF,18,19 LKLF,16 BKLF, GKLF/EZF,20,21 CPBP/Zf9, UKLF, and AP-2rep22) (Table 1). FKLF-2 thus belongs to the third group of Sp1/EKLF proteins, composed of BTEB1,23 TIEG-1,24 and FKLF/TIEG-2.8 25

Amino acid identifies of FKLF-2 zinc fingers to known proteins

| Sp1 family . | FKLF/TIEG family . | EKLF family . | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sp1 . | Sp2 . | Sp3 . | Sp4 . | BTEB1 . | TIEG-1 . | FKLF-1/ TIEG-2 . | EKLF . | BTEB2/ IKLF . | LKLF . | GKLF/EZF . | BKLF . | CPBP/Zf9 . | UKLF . | AP-2rep . |

| 72 | 63 | 71 | 71 | 82 | 73 | 77 | 64 | 65 | 63 | 64 | 65 | 64 | 64 | 65 |

| Sp1 family . | FKLF/TIEG family . | EKLF family . | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sp1 . | Sp2 . | Sp3 . | Sp4 . | BTEB1 . | TIEG-1 . | FKLF-1/ TIEG-2 . | EKLF . | BTEB2/ IKLF . | LKLF . | GKLF/EZF . | BKLF . | CPBP/Zf9 . | UKLF . | AP-2rep . |

| 72 | 63 | 71 | 71 | 82 | 73 | 77 | 64 | 65 | 63 | 64 | 65 | 64 | 64 | 65 |

Percentage of amino acid identities of zinc fingers of FKLF-2 to Sp1- or EKLF-related proteins. Note high amino acid identities to FKLF/TIEG family proteins, and at a lower degree, to Sp1 and EKLF family proteins.

The amino-terminus of FKLF-2 has significant homology to BTEB1; 29 of 72 initial amino acid residues (40%) are identical (Figure 1C). No homologies to other known proteins were detected in the amino- or the carboxyl-terminal domains. The amino-terminal domain is characterized by a high content of proline and alanine residues, whereas the carboxyl-terminal domain is rich in serine residues (Figure1A and 1B). The respective percentages of alanine, proline, and serine residues are 21%, 17%, and 6% in the amino-terminal domain, and 8%, 10%, and 26% in the carboxyl-terminal domain. The FKLF-2 protein is basically charged (isoelectric point, 10.4). Basic residues (arginines and lysines) are accumulated at amino acids 149 to 167, making a net charge of this region +6 (Figure 1B). Neither the amino- nor the carboxyl-terminal domains contain acidic regions.

Expression in human tissues

To examine the tissue-specificity of FKLF-2 mRNA expression, Northern blot hybridization using a human FKLF-2–specific RNA probe (encompassing the carboxyl-terminal coding through 3′ UTR) was performed using a commercially available membrane (MTN Blots Human I and III, Clontech), which contains poly(A)+RNA extracted from adult human stomach, thyroid gland, spinal cord, lymph node, trachea, adrenal gland, bone marrow, heart, brain, placenta, lung, liver, skeletal muscle, kidney, and pancreas. An intense band was detected at the 1.35-kb position in the bone marrow, the heart, and skeletal muscles (Figure 2A), indicating that the bone marrow and striated muscles are the major FKLF-2–expressing tissues.

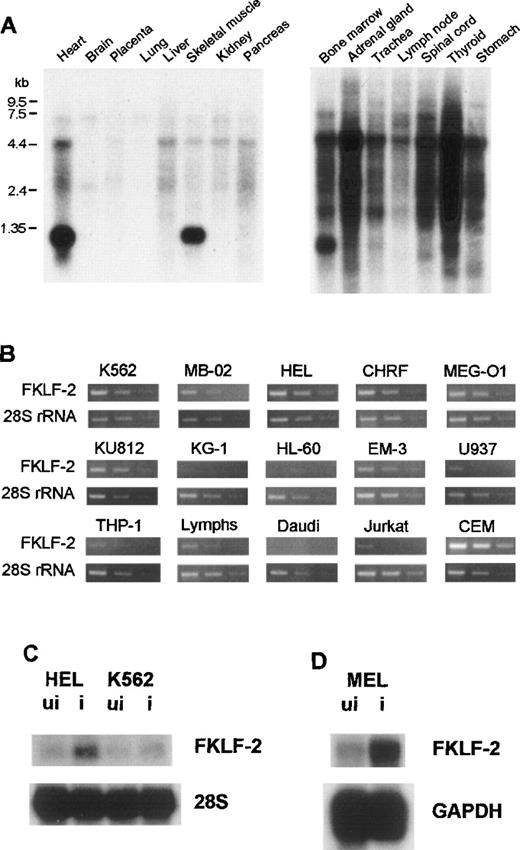

FKLF-2 mRNA.

(A) FKLF-2 mRNA expression by Northern blotting. Each lane contains 2 μg poly(A)+RNA from adult human tissues. The RNA was blotted with a specific FKLF-2 probe. A distinct band at about 135 kb was detected in the bone marrow and the heart and skeletal muscle. Another major band between 4.4 and 7.5 kb seemed to be a cross hybridization to 28S ribosomal RNA because of its size. (B) FKFL-2 mRNA expression in various cell lines by RT-PCR. Three bands in each picture show the results of amplification in different cycles; ie, from left to right, 34, 32, and 30 cycles for FKLF-2, and 22, 20, and 18 cycles for 28S rRNA. (C) FKLF-2 mRNA expression in K562 and HEL cells before (ui) and after (i) induction by Northern blottings. Two micrograms poly(A)+RNA was blotted with probes indicated. (D) FKLF-2 mRNA expression in MEL cells before and after induction (Northern blotting). Four micrograms poly(A)+RNA was blotted with probes indicated. The position of the FKLF-2 band is approximately 6 kb.

FKLF-2 mRNA.

(A) FKLF-2 mRNA expression by Northern blotting. Each lane contains 2 μg poly(A)+RNA from adult human tissues. The RNA was blotted with a specific FKLF-2 probe. A distinct band at about 135 kb was detected in the bone marrow and the heart and skeletal muscle. Another major band between 4.4 and 7.5 kb seemed to be a cross hybridization to 28S ribosomal RNA because of its size. (B) FKFL-2 mRNA expression in various cell lines by RT-PCR. Three bands in each picture show the results of amplification in different cycles; ie, from left to right, 34, 32, and 30 cycles for FKLF-2, and 22, 20, and 18 cycles for 28S rRNA. (C) FKLF-2 mRNA expression in K562 and HEL cells before (ui) and after (i) induction by Northern blottings. Two micrograms poly(A)+RNA was blotted with probes indicated. (D) FKLF-2 mRNA expression in MEL cells before and after induction (Northern blotting). Four micrograms poly(A)+RNA was blotted with probes indicated. The position of the FKLF-2 band is approximately 6 kb.

Expression in established hemopoietic cell lines

Semiquantitative RT-PCR was performed using RNA from human cell lines with erythroid, myeloid, or lymphoid phenotypes. In this assay template, cDNAs were appropriately diluted to give similar band patterns of 28S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) (Figure 2B). FKLF-2 cDNA was efficiently amplified from all the cell lines with erythroid phenotypes (K562, HEL, CHRF, MB-02, KU812, and MEG-O1). In myeloid lines, results were inconsistent; FKLF-2 cDNA was undetectable in KG-1 and HL-60 cells, whereas in EM-3, the FKLF-2 was detected at a level comparable to that observed in the erythroid lines. In lines with a B-cell phenotype, FKLF-2 cDNA could not be amplified from Daudi cells, but it was amplified from EB virus transformed lymphocytes (marked as “Lymphs” in Figure 2B). Of the 2 lines with a T-cell phenotype, FKLF-2 cDNA was weakly amplified from Jurkat cells, whereas the amplifications from CEM cells were much stronger than erythroid cells. Two monocytic lines (U937 and THP-1) gave weak FKLF-2 amplicons.

Response to inducers of differentiation

To test whether FKLF-2 expression changes on induction of erythroid differentiation, K562, HEL, and MEL cells were induced by hemin, δ-ALA, or hemin + HMBA,26,27 and FKLF-2 mRNA was assessed with Northern blotting. As shown in Figure 2C and 2D, induction of erythroid differentiation up-regulated FKLF-2 expression in all 3 cell lines. FKLF-2 thus differs from EKLF and FKLF, which fail to be up-regulated by inducers of erythroid differentiation.1 8

Activation of globin gene transcription

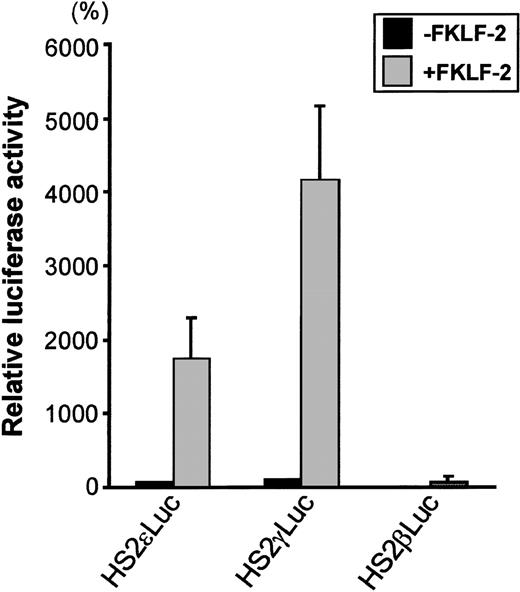

To test the role of FKLF-2 on globin gene regulation, the mammalian expression vector pSG5DD (pSG5/FKLF-2), which contains FKLF-2 cDNA, was cotransfected into K562 cells with a reporter construct containing a luciferase gene that was driven by a β globin hypersensitive site (HS) 2, and an ε, γ, or β globin gene promoter. As shown in Figure 3, FKLF-2 functions as a transcriptional activator of these promoters. In the presence of the exogenous FKLF-2, the mean luciferase activity obtained from the γ promoter construct (pHS2γLuc) was 4179% of that without FKLF-2 (considered as 100%) (Figure 3). Mean luciferase activity of the ε promoter with and without FKLF-2 were 1753% and 71%. The average luciferase activities of β promoter constructs were 1% and 76% in the absence and presence of exogenous FKLF-2, respectively.

Trans-activation of ɛ and γ and β globin gene promoters by FKLF-2.

Reporter constructs containing a luciferase gene driven by HS2 and ε, γ, or β gene promoter were transfected into K562 cells with or without pSG5/FKLF-2. Luciferase activities were corrected by protein concentrations, and expressed as relative percentages of luciferase activity of pHS2γLuc that were not cotransfected by pSG5/FKLF-2 (100%). Protein concentration was used to correct the transfection efficiency, because in our preliminary experiments we could not rule out that FKLF-2 does not activate the SV-40 promoter/enhancer of the pSVβ-Gal control plasmid.3 Data are expressed as mean (columns) ± SD (error bars) derived from multiple transfections using 2 different plasmid sets.

Trans-activation of ɛ and γ and β globin gene promoters by FKLF-2.

Reporter constructs containing a luciferase gene driven by HS2 and ε, γ, or β gene promoter were transfected into K562 cells with or without pSG5/FKLF-2. Luciferase activities were corrected by protein concentrations, and expressed as relative percentages of luciferase activity of pHS2γLuc that were not cotransfected by pSG5/FKLF-2 (100%). Protein concentration was used to correct the transfection efficiency, because in our preliminary experiments we could not rule out that FKLF-2 does not activate the SV-40 promoter/enhancer of the pSVβ-Gal control plasmid.3 Data are expressed as mean (columns) ± SD (error bars) derived from multiple transfections using 2 different plasmid sets.

Interaction with the CACCC box of the γ gene promoter

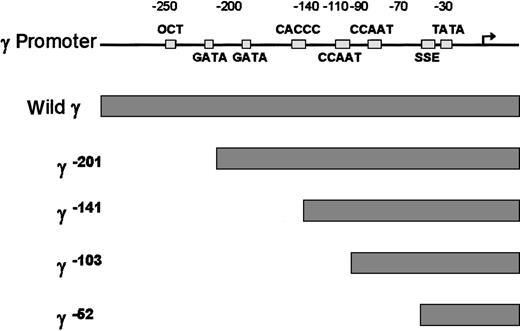

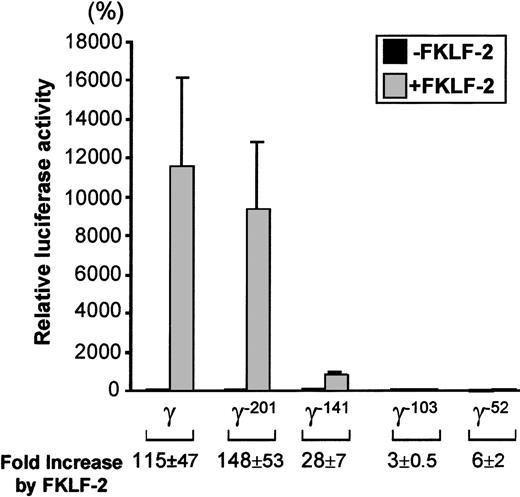

To examine which cis-element of the γ globin gene promoter is critical for the FKLF-2 function as a transcriptional activator, we prepared reporter constructs with a truncated γ gene promoter (Figure4). Because preliminary experiments showed that the γ gene promoter could also be activated by FKLF-2 in the absence of HS2 reporter, constructs lacking the HS2 were used. Four truncations were used, 2 of which have been previously characterized in transgenic mice. γ−201 contains all thecis-elements of the proximal γ promoter and lacks an upstream negative element.28 γ−141 destroys the γ CACCC box, resulting in a lack of γ gene expression in transgenic mice.28 γ−103 lacks the CACCC and the distal CAAT boxes, but it contains the proximal CAAT box, the stage selector element (SSE),9 and the TATA box. γ−52 lacks all γ gene promoter elements, except the SSE and the TATA box.

Structure of γ gene promoter.

Location of cis-elements are indicated by solid rectangles. Individual truncated γ gene promoters are shown below the wild γ promoter.

Structure of γ gene promoter.

Location of cis-elements are indicated by solid rectangles. Individual truncated γ gene promoters are shown below the wild γ promoter.

As shown in Figure 5, FKLF-2 is a powerful activator of the γ gene promoter, even in the absence of HS2. The luciferase activity of the wild γ Luc construct in the presence of FKLF-2 was 11 237% of the activity in the absence of FKLF-2 (considered as 100%) (P = .013). Strong activation was still observed in the construct pγ−201Luc (Figure 4): 9381% with FKLF-2 and 81% without FKLF-2 (P < .01). The luciferase activity dropped remarkably when the construct pγ-141Luc, which lacks a functional CACCC box was used; however, FKLF-2 activated the γ–141 promoter (869% and 33% with and without FKLF-2, respectively, P < .01), despite the fact that this promoter lacked a functional CACCC motif. Mean luciferase activities with and without FKLF-2 were 48% and 17% when the γ−103 construct was used (P = .023), and 8% and 1% when the γ−52construct (P < .01) was used. Thus, although progressive reduction of luciferase activities was observed by the sequential truncations of the γ gene promoter, FKLF-2 retained its activity on the truncated promoters. The effect of FKLF-2 on the γ gene promoter was not ablated by any of these truncations, as is demonstrated by the fold increase of luciferase activities by the addition of FKLF-2, as shown in Figure 5. These data suggested that (1) the CACCC box is the primary cis-element interacting with FKLF-2; and (2) FKLF-2 may interact with the SSE or it may activate the γ globin gene promoter through the TATA box or its surrounding sequences.

Effect of truncation deletions of γ gene promoter on FKLF-2 activity.

Reporter constructs containing a luciferase gene driven by various γ gene promoters depicted in Figure 4 were tested in K562 cells. Luciferase activities were expressed as relative percentages of luciferase activity of pγLuc that were not cotransfected by pSG5/FKLF-2 (100%). Fold increases (expressed as mean ± SD) of luciferase activities by FKLF-2 compared with those in the absence of the transactivator are shown below.

Effect of truncation deletions of γ gene promoter on FKLF-2 activity.

Reporter constructs containing a luciferase gene driven by various γ gene promoters depicted in Figure 4 were tested in K562 cells. Luciferase activities were expressed as relative percentages of luciferase activity of pγLuc that were not cotransfected by pSG5/FKLF-2 (100%). Fold increases (expressed as mean ± SD) of luciferase activities by FKLF-2 compared with those in the absence of the transactivator are shown below.

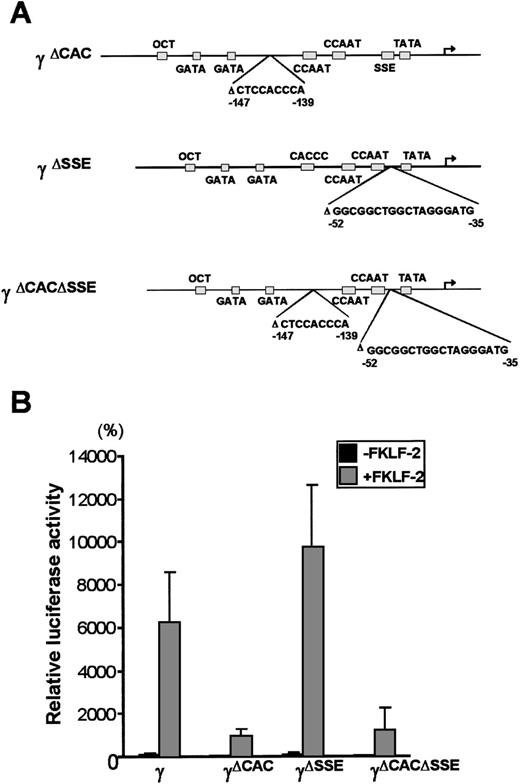

Interaction with other cis elements of the proximal γ gene promoter

To further analyze the interaction between FKLF-2 and thecis elements of the γ gene promoter, reporter constructs with an internal deletion of the CACCC (pγ[ΔCAC]Luc), or the SSE element (pγ[ΔSSE]Luc), or both elements (pγ[ΔCACΔSSE]Luc) (Figure 6A) were produced. These reporter constructs were transiently transfected into K562 cells with and without FKLF-2. As shown in Figure 6B powerful γ promoter activation by FKLF-2 was consistently observed. Similarly to the pattern observed in γ−141 truncation (Figure 5), deletion of a 9 bp CACCC sequence (γ[ΔCAC]) reduced γ gene promoter activity (Figure 6B). However, FKLF-2 still activated the γ(ΔCAC) promoter: The mean luciferase activities in the presence and the absence of exogenous FKLF-2 were 991% and 50%, respectively (the wild-type γ promoter activity in the absence of FKLF-2 was considered as 100%).

Deletions of γ gene promoter.

(A) Internal deletions of γ gene promoter. CACCC and stage selector (SSE) sequences were deleted from the γ gene promoter as indicated. (B) Effect of deletion of CACCC box and SSE on γ promoter activation by FKLF-2. Reporter constructs containing a luciferase gene driven by γ gene promoters with internal deletions depicted in Figure 6A were tested in K562 cells.

Deletions of γ gene promoter.

(A) Internal deletions of γ gene promoter. CACCC and stage selector (SSE) sequences were deleted from the γ gene promoter as indicated. (B) Effect of deletion of CACCC box and SSE on γ promoter activation by FKLF-2. Reporter constructs containing a luciferase gene driven by γ gene promoters with internal deletions depicted in Figure 6A were tested in K562 cells.

Deletion of SSE in the γ(ΔSSE) construct, in which nucleotides −35 to −52 relative to the cap site were deleted, did not significantly affect the γ promoter activity: The mean luciferase activities with and without FKLF-2 were 9754% and 112%, respectively, (Figure 6B) indicating that SSE is not required for activation of the γ gene promoter by FKLF-2.

Deletion of both the CACCC box and the SSE elements in the (γ[ΔCACΔSSE]) construct failed to ablate the activation of γ gene by the FKLF-2: The average luciferase activity without exogenous FKLF-2 was 68%, whereas it was 1254% with FKLF-2 (Figure 6B).

The results described above indicate that FKLF-2 interacts with at least 2 regions of the γ globin gene promoter: (1) the CACCC element and (2) the TATA box or its surrounding DNA sequences.

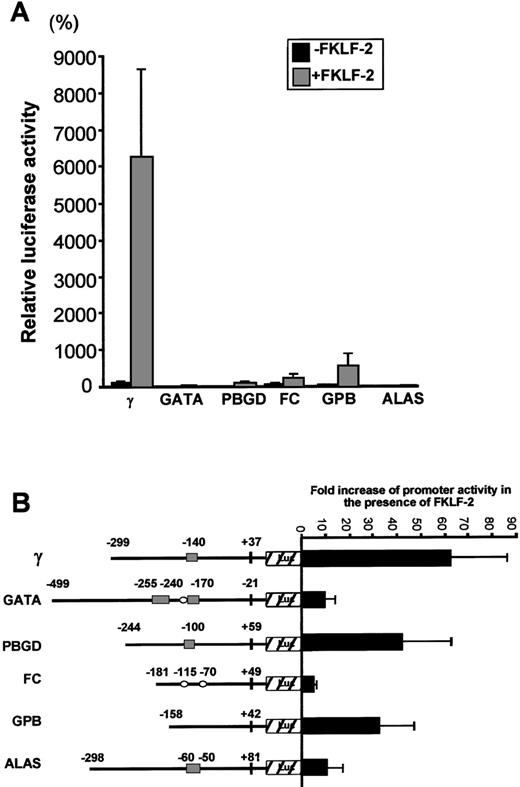

FKLF-2 activates nonglobin erythroid gene promoters

To test whether FKLF-2 functions as a transcriptional activator of other promoters with CACCC (or GC) motifs, we performed transactivation assays using FKLF-2 and reporter constructs carrying promoters of 5 genes expressed in erythroid cells, ie, GATA-1, GPB, FC, PBGD, and ALAS. Because of the high level of activation of the γ gene promoter in the absence of HS2, reporter constructs lacking the HS2 enhancer were used.

Luciferase activities driven by these promoters are shown in Figure7A. Luciferase activity from pγLuc in the absence of FKLF-2 was considered as 100%. Mean luciferase activities in the absence and the presence of exogenous FKLF-2 were as follows: 5% and 33% for GATA (P = .059); 3% and 117% for PBGD (P < .001); 48% and 241% for FC (P = .025); 20% and 536% for GPB (P = .043); and 3% and 17% for ALAS (P < .005). Therefore, FKLF-2 activated all the erythroid promoters we used in our assay, although with different intensity. The γ globin and the PBGD and GPB genes showed the highest level of activation, whereas the activation of GATA, FC, and ALAS was low (Figure 7B). The level of activation of these promoters by FKLF-2 did not correlate well with the presence of CACCC or GC motifs, or the number of the motifs. For example, the GPB promoter, which lacks typical CACCC or GC-rich sequences, showed higher activation than the GATA-1 promoter, which contains 3 CACCC motifs and 1 GC-box (Figure7B). This observation suggests that the overall context of the promoter is more important for FKLF-2 function than the mere presence of a consensus motif in the DNA sequence. A similar conclusion was previously reached with our studies on EKLF3 and FKLF.8

Effect of FKLF-2 on various erythroid promoters.

(A) Reporter constructs containing a luciferase gene driven by either GATA-1 (GATA), porphobilinogen deaminase (PBGD), ferrochelatase (FC), glycophorin B (GPB), or 5-aminolevulinate synthase (ALAS) promoter were cotransfected with or without pSG5/FKLF-2. (B) Fold increase of luciferase activities by FKLF-2 from the reporter constructs used in this experiment. Numbers above the promoters are base pair distances from the cap site (γ, GPB, FC, PBGD, and ALAS) or from the end of exon 1 (GATA), and they indicate the upstream ends of the promoter sequences cloned, and the positions of the CACCC and the GC-rich sequences (solid rectangles and open ellipses, respectively).

Effect of FKLF-2 on various erythroid promoters.

(A) Reporter constructs containing a luciferase gene driven by either GATA-1 (GATA), porphobilinogen deaminase (PBGD), ferrochelatase (FC), glycophorin B (GPB), or 5-aminolevulinate synthase (ALAS) promoter were cotransfected with or without pSG5/FKLF-2. (B) Fold increase of luciferase activities by FKLF-2 from the reporter constructs used in this experiment. Numbers above the promoters are base pair distances from the cap site (γ, GPB, FC, PBGD, and ALAS) or from the end of exon 1 (GATA), and they indicate the upstream ends of the promoter sequences cloned, and the positions of the CACCC and the GC-rich sequences (solid rectangles and open ellipses, respectively).

Discussion

The Sp1/EKLF multigene family to which FKLF-2 belongs is composed of 3 groups, the EKLF group, the Sp1 group, and a third subgroup composed of BTEB1, TIEG-1, and FKLF/TIEG-2. This group is characterized by intermediate amino acid homology to both Sp1 and EKLF subfamilies8; FKLF-2 is the fourth member of this group. In addition to sharing highly homologous zinc finger motifs, FKLF-2 and BTEB1 show a high homology at their amino-terminal end. Homologies in the amino-terminal domains of 30% to 40% is characteristic of other Sp1- or EKLF-like proteins (Table 2).

FKLF-2 has a number of features that distinguish it from FKLF. First, FKLF-2 activates mainly the γ gene promoter, whereas FKLF activates mainly the ε gene promoter. Second, although the activity of FKLF is totally dependent on the presence of the −140 CACCC box, FKLF-2 activates the γ gene promoter mainly through the CACCC box and, to a lesser degree, through the TATA box or a neighboring sequence. Third, in contrast to FKLF and EKLF, which are not up-regulated after induction of erythroleukemia lines,1,8 FKLF-2 mRNA expression is up-regulated after induction of erythroid differentiation. Fourth, in addition to the globin genes, FKLF-2 activated all the erythroid promoters we tested. Perhaps in addition to its effect on γ globin activation, FKLF is involved in the molecular events of erythroid differentiation. Expression studies of adult human tissues using Northern hybridization showed that FKLF-2 is expressed only in bone marrow and striated muscle. This is of special interest in view of the recent evidence29 30 that muscle-origin stem cells can repopulate the hematopoiesis of sublethally irradiated animals.

The activation of the γ gene promoter by FKLF-2 is not enhanced when HS2 is present in the constructs used for the transient expression assays. Thus, although FKLF-2 increases γ promoter expression from 62- to 115-fold in the absence of HS2, it increased expression only 42-fold in the presence of HS2. Such results are compatible with the interpretation that FKLF-2 is a powerful activator of γ gene transcription independent of the presence of an enhancer. The results also indicate that, if FKLF-2 interacts with LCR, the interaction cannot be mediated by HS2, despite the fact that this HS contains 3 CACCC motifs. As in the case of EKLF, other DNase I hypersensitive sites, such as HS3,7,31 32 might be important for this interaction.

The murine FKLF-2 was cloned from the yolk sac and its human homologue from the human fetal liver. By Northern hybridization, the human adult bone marrow appears to be the adult tissue in which FKLF-2 is predominantly expressed. Thus, FKLF-2 is expressed in embryonic, fetal, and adult erythropoiesis. Expression in the adult stage of erythropoiesis appears to be inconsistent with a role of FKLF-2 in the regulation of a fetal gene such as the γ gene. However, it is well established that there is γ gene expression in the adult stage of erythropoiesis, and it is increased substantially in individuals with various pathologic conditions.33 Therefore, expression in adult bone marrow is not incompatible with the possibility that FKLF-2 functions as a γ gene activator.

Reprints:George Stamatoyannopoulos, Division of Medical Genetics, University of Washington, Box 357720, Seattle, WA 98195; e-mail: gstam@u.washington.edu.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal