Abstract

Antigens of the Rh blood group system are encoded by 2 homologous genes, RHD and RHCE, that produce 2 red cell membrane proteins. The D-negative phenotype is considered to result, almost invariably, from homozygosity for a complete deletion ofRHD. The basis of all PCR tests for predicting fetal D phenotype from DNA obtained from amniocytes or maternal plasma is detection of the presence of RHD. These tests are used in order to ascertain the risk of hemolytic disease of the newborn. We have identified an RHD pseudogene (RHD ψ) in Rh D-negative Africans. RHDψ contains a 37 base pair (bp) insert in exon 4, which may introduce a stop codon at position 210. The insert is a sequence duplication across the boundary of intron 3 and exon 4.RHDψ contains another stop codon in exon 6. The frequency ofRHDψ in black South Africans is approximately 0.0714. Of 82 D-negative black Africans, 66% hadRHDψ, 15% had the RHD-CE-D hybrid gene associated with the VS+ V– phenotype, and only 18% completely lackedRHD. RHDψ is present in about 24% of D-negative African Americans and 17% of D-negative South Africans of mixed race. No RHD transcript could be detected in D-negative individuals with RHDψ, probably as a result of nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Existing PCR-based methods for predicting D phenotype from DNA are not suitable for testing Africans or any population containing a substantial proportion of people with African ethnicity. Consequently, we have developed a new test that detects the 37 bp insert in exon 4 of RHDψ. (Blood. 2000; 95:12-18)

Rh is a highly complex red cell blood group system with 52 antigens and numerous phenotypes.1,2 The Rh antigens are encoded by 2 closely linked homologous genes, each consisting of 10 coding exons. RHCE encodes the Cc and Ee antigens, andRHD encodes the D antigen. There are also many uncommon fusion genes, comprising part of RHCE and part of RHD, which may encode abnormal D and CcEe antigens and 1 or more low- frequency Rh antigens.3 4

The most important Rh polymorphism from the clinical aspect is the D polymorphism. About 82%-85% of Caucasians are D-positive, the remainder lack the D antigen. The D-negative phenotype has a frequency ranging between 3% and 7% in Africans and <1% in the people from the Far East.1 D-negative red cells lack the D protein, and alloanti-D consists of antibodies to a variety of epitopes on the D polypeptide. Colin et al5 found that the D-negative phenotype resulted from homozygosity for a complete deletion ofRHD. Rare exceptions to this molecular basis of D-negative, in which at least some RHD exons are present, have been described. In almost all these exceptions, the aberrant RHD belongs to a haplotype producing C antigen. Examples found in Caucasians include RHD containing a nonsense mutation6 or a 4- nucleotide deletion,7 andRHD-CE-D fusion genes containing RHD exons 1 and 10 orRHD exons 1-3 and exons 9 and 10, with the remainder of the exons derived from RHCE.8,9 An RHD-CE-Dfusion gene, in which the 3′ end of exon 3 plus exons 4-8 are derived from RHCE, is sometimes associated with a D-negative phenotype in people of African origin.10 In 130 D-negative Japanese, 36 (28%) had an apparently intact RHD, 2 had at least exon 10 of RHD, and 1 of these also had RHD exon 3.11 Despite these variants, however, it is generally accepted that lack of RHD is the usual molecular background for the D-negative phenotype.

The D antigen is of clinical importance because anti-D antibodies are capable of causing severe hemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn (HDN), resulting in hydrops fetalis and fetal death. In those severely affected infants who are born alive, jaundice may lead to kernicterus.12 The prevalence of RhD HDN has been greatly reduced since the 1960s by the introduction of anti-D immunoglobulin prophylaxis, which prevents D-negative mothers from being immunized by fetal D-positive red cells as a result of feto-maternal hemorrhage at parturition. Some D-negative women, however, still produce anti-D for a variety of reasons including undetected antepartum feto-maternal hemorrhage and failure to administer anti-D, and any subsequent D-positive fetus is at risk from HDN. It is now common practice for anti-D immunoglobulin to be administered antenatally as well as postnatally in an attempt to reduce the risk of D immunization.

Discovery of the molecular basis of the D polymorphism created the possibility of predicting fetal D phenotype from fetal DNA derived from amniocytes obtained by amniocentesis. D phenotyping of the fetus of a D-negative woman with anti-D provides valuable information for predicting the risk of HDN and for subsequent management of the pregnancy. The first tests to be devised involved a polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The tests either determined the presence or absence ofRHD-specific sequences in exon 10 or exon 7 or recognized the size differences between introns 4 of RHD andRHCE.13-16 These techniques were found to be unreliable.16 The absence of certain RHD regions in hybrid genes encoding partial D antigens may predict a D-negative phenotype, and the presence of some RHD regions in genes encoding no D antigen may predict a D-positive phenotype. In order to avoid these complications, methods where more than 1 region ofRHD is detected in a single PCR were introduced.6,11 17

Amniocentesis is a highly invasive procedure and not without risk to the fetus. It may also enhance the risk of maternal immunization. Methods have been described for predicting D phenotype from fetal DNA in maternal plasma. It has been proposed that these techniques could be used for testing all D-negative pregnant women to ascertain whether they require administration of antenatal anti-D immunoglobulin.18 19 Testing would reduce wastage of this valuable resource by avoiding anti-D immunoglobulin administration to women with a D-negative fetus.

All techniques for predicting D phenotype from DNA or mRNA are based on the dogma that, with only very rare exceptions, the D-negative phenotype results from the absence of all or most of the RHDgene. Most tests, however, have been performed on people of European origin, and the molecular basis of D polymorphism has not been adequately investigated in other races, particularly in people of African origin. We have tested for the presence of the RHD gene in Africans and African Americans and found that the majority of D-negative Africans and about a quarter of D-negative African Americans have an inactive RHD gene with a 37 base pair (bp) insert and a nonsense mutation; the remainder have either the RHD-CE-D gene or a complete deletion of the RHD gene.

Materials and methods

Blood samples

D-negative blood samples were obtained from black African blood donors from South Africa, Zimbabwe, and Ghana; from South African donors of mixed race, referred to as “Coloured” in South Africa; and from African American donors, selected on the basis of appearance, from Shreveport, Louisiana. Blood samples from D-positive black South Africans were derived from another study.20 All blood samples were collected into a citrate-phosphate-dextrose (CPD) anticoagulant. Blood samples used for screening purposes were the by-product of blood donation and were collected according to the approved protocol of the transfusion center involved. Whole units of blood, for transcription analysis, were taken with informed consent.

Serological studies

All red cell samples were tested for D, C, c, E, e, G, VS, and Rh32 antigens. VS+ samples were also tested for V antigen. Serological tests were performed by the method most suited to the particular reagent: direct hemagglutination, with native or papain-treated cells, or indirect hemagglutination with antihuman IgG (BPL, Elstree, England). All D-negative red cells were tested by an antiglobulin test with 2 potent alloanti-D that are known to react with red cells of all partial D phenotypes. An acid-elution method (Elu-kit II, Gamma Biologicals, Houston, TX) was used for adsorption/elution tests with anti-D.

Molecular analyses on genomic DNA

Genomic DNA was isolated from mononuclear cells by a standard phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol procedure or from whole blood with a DNA purification kit (Promega, Madison, WI). PCR primers are listed in Table 1. The method used for RHDscreening, the multiplex PCR described by Avent et al,6detected the presence of RHD exon 10 and intron 4 and RHCE intron 4, as an internal control.

Oligonucleotide primers for amplifying whole exons or for identifying the presence of exons

| Exon . | Primer Name . | Direction . | Specificit . | Primer Position* . | Sequence (5′ to 3′) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | RH1F (rb13) | S | D + CE | Promoter −675 to −652 | CTAGAGCCAAACCCACATCTCCTT |

| RH1R (re11d) | AS | D + CE | Intron 1 129 to 106 | AGAAGATGGGGGAATCTTTTTCCT | |

| RHD1F (re01) | S | D | Promoter −149 to −132 | ATAGAGAGGCCAGCACAA | |

| RHIN1R | AS | D + CE | Intron 1 84 to 64 | TCTGTGCCCCTGGAGAACCAC | |

| 2 | RHEX2IN1F (re 13) | S | D + CE | Intron 1 −72 to −53 | ACTCTAATTTCATACCACCC |

| RH2R (re23) | AS | D + CE | Intron 2 250 to 227 | AAAGGATGCAGGAGGAATGTAGGC | |

| 3 | RH3F (ra21) | S | D + CE | Intron 2 2823 to 2842 | GTGCCACTTGACTTGGGACT |

| RHDIN2F (rb20d) | S | D | Intron 2 −25 to −8 | TCCTGGCTCTCCCTCTCT | |

| RH3R (rb21) | AS | D + CE | Intron 3 28 to 11 | AGGTCCCTCCTCCAGCAC | |

| RHDEX3F | S | D | Exon 3 364 to 383 | TCGGTGCTGATCTCAGTGGA | |

| RHDEX3R | AS | D | Exon 3 474 to 455 | ACTGATGACCATCCTCAGGT | |

| 4 | RHDIN3F | S | D | Intron 3 −36 to −16 | GCCGACACTCACTGCTCTTAC |

| RHD4R (rb12) | AS | D | Intron 4 197 to 174 | TCCTGAACCTGCTCTGTGAAGTGC | |

| RHDEX4F | S | D | Exon 4 582 to 602 | AACGGAGGATAAAGATCAGAC | |

| RHDIN4R | AS | D | Intron 4 193 to 173 | GAACCTGCTCTGTGAAGTGCT | |

| 5 | RHD5F (rb11) | S | D | Intron 4 −267 to −243 | TACCTTTGAATTAAGCACTTCACAG |

| RHIN5R | AS | D + CE | Intron 5 73 to 56 | GTGGGGAGGGGCATAAAT | |

| RHDMULTI5F | S | D | Exon 5 648 to 667 | GTGGATGTTCTGGCCAAGTT | |

| RHDMULTI5R | AS | D | Intron 6 16 to exon 5 799 | GCAGCGCCCTGCTCACCTT | |

| 6 | RH6F (rf51 | S | D + CE | Intron 5 −332 to −314 | CAAAAACCCATTCTTCCCG |

| RHDIN6R | AS | D | Intron 6 41 to 21 | CTTCAGCCAAAGCAGAGGAGG | |

| RHEX6F | S | D + CE | Exon 6 898 to 916 | GTGGCTGGGCTGATCTACG | |

| RHDEX6R | AS | D | Intron 7 15 to exon 6 932 | TGTCTAGTTTCTTACCGGCAAGT | |

| RHDΨEX6R | AS | DΨ | Exon 6 824 to 807 | AACACCGCACTGTGCTCC | |

| 7 | RHDIN6F (re621) | S | D | Intron 6 −102 to −85 | CATCCCCCTTTGGTGGCC |

| RHDIN7R (re75) | AS | D | Intron 7 168 to 151 | AAGGTAGGGGCTGGACAG | |

| RHEX7F2 | S | D + CE | Exon 7 949 to 967 | AACCGAGTGCTGGGGATTC | |

| RHDEX7R | AS | D | Exon 7 1059 to intron 8 7 | ACCCACATGCCATTGCCGGCT | |

| 9 | RHD9F | S | D | Exon 9 1154 to 1170 | AACAGGTTTGCTCCTAAATCTT |

| RHEX9R | AS | D | Exon 9 1219 to 1193 | AAACTTGGTCATCAAAATATTTAACCT | |

| 10 | RH10F (re91) | S | D + CE | Intron 9 −67 to −45 | CAAGAGATCAAGCCAAAATCAGT |

| RHD10R (rr4) | AS | D | 3′ UTR 1541 to 1522 | AGCTTACTGGATGACCACCA |

| Exon . | Primer Name . | Direction . | Specificit . | Primer Position* . | Sequence (5′ to 3′) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | RH1F (rb13) | S | D + CE | Promoter −675 to −652 | CTAGAGCCAAACCCACATCTCCTT |

| RH1R (re11d) | AS | D + CE | Intron 1 129 to 106 | AGAAGATGGGGGAATCTTTTTCCT | |

| RHD1F (re01) | S | D | Promoter −149 to −132 | ATAGAGAGGCCAGCACAA | |

| RHIN1R | AS | D + CE | Intron 1 84 to 64 | TCTGTGCCCCTGGAGAACCAC | |

| 2 | RHEX2IN1F (re 13) | S | D + CE | Intron 1 −72 to −53 | ACTCTAATTTCATACCACCC |

| RH2R (re23) | AS | D + CE | Intron 2 250 to 227 | AAAGGATGCAGGAGGAATGTAGGC | |

| 3 | RH3F (ra21) | S | D + CE | Intron 2 2823 to 2842 | GTGCCACTTGACTTGGGACT |

| RHDIN2F (rb20d) | S | D | Intron 2 −25 to −8 | TCCTGGCTCTCCCTCTCT | |

| RH3R (rb21) | AS | D + CE | Intron 3 28 to 11 | AGGTCCCTCCTCCAGCAC | |

| RHDEX3F | S | D | Exon 3 364 to 383 | TCGGTGCTGATCTCAGTGGA | |

| RHDEX3R | AS | D | Exon 3 474 to 455 | ACTGATGACCATCCTCAGGT | |

| 4 | RHDIN3F | S | D | Intron 3 −36 to −16 | GCCGACACTCACTGCTCTTAC |

| RHD4R (rb12) | AS | D | Intron 4 197 to 174 | TCCTGAACCTGCTCTGTGAAGTGC | |

| RHDEX4F | S | D | Exon 4 582 to 602 | AACGGAGGATAAAGATCAGAC | |

| RHDIN4R | AS | D | Intron 4 193 to 173 | GAACCTGCTCTGTGAAGTGCT | |

| 5 | RHD5F (rb11) | S | D | Intron 4 −267 to −243 | TACCTTTGAATTAAGCACTTCACAG |

| RHIN5R | AS | D + CE | Intron 5 73 to 56 | GTGGGGAGGGGCATAAAT | |

| RHDMULTI5F | S | D | Exon 5 648 to 667 | GTGGATGTTCTGGCCAAGTT | |

| RHDMULTI5R | AS | D | Intron 6 16 to exon 5 799 | GCAGCGCCCTGCTCACCTT | |

| 6 | RH6F (rf51 | S | D + CE | Intron 5 −332 to −314 | CAAAAACCCATTCTTCCCG |

| RHDIN6R | AS | D | Intron 6 41 to 21 | CTTCAGCCAAAGCAGAGGAGG | |

| RHEX6F | S | D + CE | Exon 6 898 to 916 | GTGGCTGGGCTGATCTACG | |

| RHDEX6R | AS | D | Intron 7 15 to exon 6 932 | TGTCTAGTTTCTTACCGGCAAGT | |

| RHDΨEX6R | AS | DΨ | Exon 6 824 to 807 | AACACCGCACTGTGCTCC | |

| 7 | RHDIN6F (re621) | S | D | Intron 6 −102 to −85 | CATCCCCCTTTGGTGGCC |

| RHDIN7R (re75) | AS | D | Intron 7 168 to 151 | AAGGTAGGGGCTGGACAG | |

| RHEX7F2 | S | D + CE | Exon 7 949 to 967 | AACCGAGTGCTGGGGATTC | |

| RHDEX7R | AS | D | Exon 7 1059 to intron 8 7 | ACCCACATGCCATTGCCGGCT | |

| 9 | RHD9F | S | D | Exon 9 1154 to 1170 | AACAGGTTTGCTCCTAAATCTT |

| RHEX9R | AS | D | Exon 9 1219 to 1193 | AAACTTGGTCATCAAAATATTTAACCT | |

| 10 | RH10F (re91) | S | D + CE | Intron 9 −67 to −45 | CAAGAGATCAAGCCAAAATCAGT |

| RHD10R (rr4) | AS | D | 3′ UTR 1541 to 1522 | AGCTTACTGGATGACCACCA |

Indicates that numbers for exon positions represent nucleotide position in cDNA. Numbers for introns are relative to adjacent exons. Primer names in parentheses are as described by Wagner et al.21 Introduced mismatch in RHDΨEX6R is underlined.

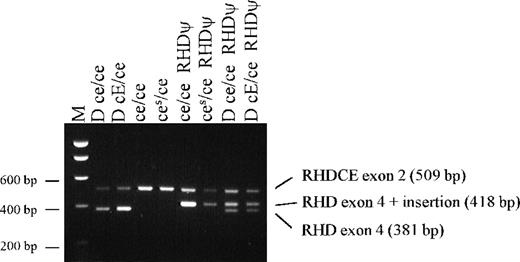

The method for screening for the 37 bp insert of RHD exon 4 was a PCR with a sense primer (RHDIN3F) in intron 3 and anRHD-specific antisense primer (RHD4R) in intron 4 (Table 1). Electrophoresis of amplification products in 1.5% agarose gel revealed a 381 bp product from wild type RHD and a 418 bp product fromRHD with the 37 bp insert. As an internal control, primers RHEX2IN1F and RH2R amplified a 509 bp product across exon 2 ofRHD and RHCE for all samples. Screening for theRHD exon 6 T807G nonsense mutation involved PCR with RH6F (sense primer) and a sequence-specific antisense primer, RHDψE × 6R (Table 1).

The sequences of RHD exons 1, 3-7, and 10 were determined by direct sequencing of PCR products. Many of the primers used for exon amplification were described by Wagner et al21 (Table 1). Following agarose-gel electrophoresis, PCR products were cut out of the gel, purified (QIAEX II kit; QIAGEN, Dorking, England), and sequenced (373A DNA sequencer; Applied Biosystems, Warrington, England).

Screening for the presence of RHD exons 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 9 was performed in separate PCRs, with pairs of primers (Table 1) in which at least 1 had an RHD-specific sequence by the conditions employed. The test for an RHD-CE hybrid exon 3, characteristic of the D-negative, (C)ces(r'S) complex, utilizes anRHD-specific primer to the 5′ end of exon 3 and anRHCE-specific primer to the 3′ end.20 A test for identifying the C733G polymorphism in RHCE exon 5, which encodes a Leu245Val substitution in the RhCcEe protein responsible for the absence or presence of VS antigen, involved anRHCE-specific sense primer in intron 4 and an allele-specific antisense primer in exon 5 of RHCE.20

Transcript analysis

Erythroblasts were cultured from a D-negative black South African with the RHD 37 bp insert. Mononuclear cells were separated from whole blood in CPD (Histopaque-1077 gradient; Sigma-Aldrich, Poole, England), and contaminating red cells were lysed in ammonium chloride. CD34+ cells were isolated (Mini-MACS columns; Miltenyi Biotech, Bisley, England) by 2 cycles of positive selection with anti-CD34 and immunomagnetic beads. The isolated cells were then cultured in the presence of fetal-calf serum (N.V. HyClone, Belgium), recombinant human (rH) erythropoietin (Boehringer Mannheim, Frankfurt, Germany), rH granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (R&D Systems, Abingdon, England), and rH interleukin-3 (IL-3) (R&D Systems), as described by Malik et al.22

After 11 days, cells were harvested and analyzed for the presence of glycophorin A (GPA) and Rh protein. This was accomplished using flow cytometry with monoclonal antibodies BRIC 256 and BRIC 69 (IBGRL Research Products, Bristol, England). BRIC 256 detects an epitope on the extracellular domain of GPA, and BRIC 69 detects an extracellular epitope common to the RHCcEe and RhD polypeptides. About 80% of the cells expressed both Rh protein and GPA.

We isolated mRNA from 106 cells (The PolyATtract System 1000 kit; Promega). First-strand cDNA for PCR amplification was prepared with oligo (dT16) as the primer and avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase (Pharmacia, Milton Keynes, England).23 cDNA was amplified with the following primers: 5′-CTGAGGATGGTCATCAGTAA-3′ (nt 457-476, exon 3 of RHCE and RHD) and 5′-GAGATCAGCCCAGCCAC-3′ (nt 914-898, exon 6 of RHCEand RHD). The 458 bp product was isolated by gel purification and sequenced. In addition, an RHD-specific PCR was performed with a sense primer in exon 3 (RHDEX3F, Table 1) and an antisense primer in exon 7 (5′-ACCCAGCAAGCTGAAGTTGTAGCC-3′) to give a 645 bp product with RHD cDNA. As a control, anRHCE-specific PCR was carried out with a sense primer in exon 3 (5′-TCGGTGCTGATCTCAGCGGG-3′) and an antisense primer in exons 8 and 7 (5′-CAATCATGCCATTGCCGTTCCA-3′) to give a 715 bp product with RHCE cDNA.

Reticulocyte RNA was extracted from a D-negative black South African by isolating CD71+ cells from 10 mL of phosphate buffered saline–washed peripheral blood using anti-CD71 magnetic beads (Dynal, Wirral, England). Total RNA was extracted with an RNA extraction kit (SV total RNA, Promega), and first-strand cDNA was then synthesized. RHD transcripts were analyzed by the amplification of 2 overlapping cDNA fragments, 1 encompassing exons 1-7 and the other exons 7-10. PCR primers were exons 1-7, 5′-TCCCCATCATAGTCCCTCTG-3′ and RHDIN7R (Table 1), and exons 7-10, 5′-TGGTGCTTGATACCGCGGAG-3′ and 5′-AGTGCATAATAAATGGTGAG-3′. PCR conditions were as follows: denaturation at 94°C for 1 minute; annealing at 55°C for 1 minute, and extension at 72°C for 2 minutes (ExpandTM RTPCR kit; Boehringer, Lewes, Sussex, England) for 30 cycles with 2.5 mmol/L Mg2+ (final concentration) supplied with the kit. A final 30-minute incubation at 72°C was performed to maximize the d(A) tailing of the PCR products, which were cloned into the pCRII vector (Invitrogen, Groningen, The Netherlands) and sequenced on both strands.

A new multiplex PCR-based screening test for fetal D typing

A 10-primer multiplex PCR-based method has been developed for determining the presence of RHD exon 7 and intron 4, the 37 bp insert in RHDψ exon 4, and the RHCE C andc alleles. The primers and their concentrations are shown in Table 2. Thirty cycles of PCR were performed at 94°C for 1 minute, 65°C for 1 minute, and 72°C for 3 minutes 30 seconds.

Multiplex PCR test primers for predicting Rh D and C/c phenotype and the presence of the RHD pseudogene

| Primer Name . | Sequence (5′ to 3′) . | Concentration (ng/μL) . | Product Size (bp) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exon7/for | AGCTCCATCATGGGCTACAA | 1 | 95 |

| Exon 7/rev | ATTGCCGGCTCCGACGGTATC | 1 | |

| Intron 3/for 1 | GGGTTGGGCTGGGTAAGCTCT | 1 | 498 or 535 |

| Intron 4/rev | GAACCTGCTCTGTGAAGTGCT | 4 | |

| Intron 3/for 2 | AACCTGGGAGGCAAATGTT | 10 | 250 |

| Exon 4 insert/rev | AATAAAACCCAGTAAGTTCATGTGG | 10 | |

| C/for | CAGGGCCACCACCATTTGAA | 12 | 320 |

| C/rev | GAACATGCCACTTCACTCCAG | 1.5 | |

| c/for | TCGGCCAAGATCTGACCG | 7 | 177 |

| c/rev | TGATGACCACCTTCCCAGG | 7 |

| Primer Name . | Sequence (5′ to 3′) . | Concentration (ng/μL) . | Product Size (bp) . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exon7/for | AGCTCCATCATGGGCTACAA | 1 | 95 |

| Exon 7/rev | ATTGCCGGCTCCGACGGTATC | 1 | |

| Intron 3/for 1 | GGGTTGGGCTGGGTAAGCTCT | 1 | 498 or 535 |

| Intron 4/rev | GAACCTGCTCTGTGAAGTGCT | 4 | |

| Intron 3/for 2 | AACCTGGGAGGCAAATGTT | 10 | 250 |

| Exon 4 insert/rev | AATAAAACCCAGTAAGTTCATGTGG | 10 | |

| C/for | CAGGGCCACCACCATTTGAA | 12 | 320 |

| C/rev | GAACATGCCACTTCACTCCAG | 1.5 | |

| c/for | TCGGCCAAGATCTGACCG | 7 | 177 |

| c/rev | TGATGACCACCTTCCCAGG | 7 |

Results

Identification of an RHD pseudogene in D-negative Africans

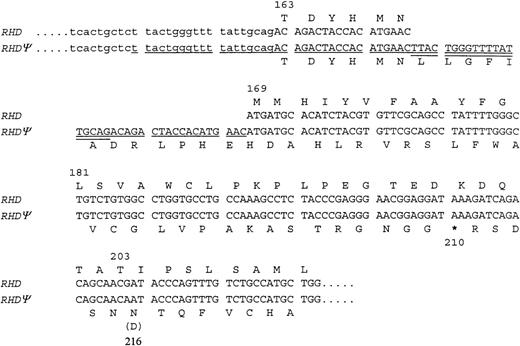

An RHD gene was found in some D-negative Africans. Sequencing of exon 4 of this apparently inactive RHD revealed a 37 bp insert (Figure 1). This insert appears to introduce a reading frameshift and a potential translation-termination codon at codon 210. The 37 bp insert is a duplication of a sequence spanning the intron 3–exon 4 boundary (Figure 1). Sequencing of exons 1, 3-7, and 10 of the inactiveRHD revealed additional changes from the common RHDsequence. In exon 4, there is a G to A point mutation at nucleotide 609 (original position). Normally, this would not result in an amino acid change, but the 37 bp insertion and subsequent frameshift gives rise to an aspartic acid to asparagine substitution at codon 203 (original reading frame) or codon 216 (new reading frame) (Figure 1). In exon 5, 3 missense mutations (G654C, T667G, C674T) were detected, encoding Met218Ile, Phe223Val, and Ser225Phe substitutions. In exon 6, a T807G transversion changes the codon for Tyr269 (TAT) to a translation-termination codon (TAG). PCR with a sequence-specific primer revealed that all individuals with the RHD 37 bp insert also had the T807G nonsense mutation. The inactive RHD gene will be referred to here as RHDψ.

Nucleotide and encoded amino acid sequence for the 3′ end of intron 3 and the 5′ end of exon 4 of RHDand RHDψ.

The region of the 37 bp duplication is underlined (single and double). The putative exon sequence derived from intron 3 is double-underlined.* Indicates a translation-termination codon.

Nucleotide and encoded amino acid sequence for the 3′ end of intron 3 and the 5′ end of exon 4 of RHDand RHDψ.

The region of the 37 bp duplication is underlined (single and double). The putative exon sequence derived from intron 3 is double-underlined.* Indicates a translation-termination codon.

Two samples from D+ C– c+ E– e+ Africans were sequenced as controls. Both had the wild type sequence in exon 4, except 1 had a C602G transversion encoding Thr201Arg. One had the wild type sequence in exon 5, the other had the Phe223Val change. Neither of the African control samples had the T807G nonsense mutation, but 1 had a G819A silent mutation (codon for Ala273). Thr201Arg, Phe223Val, and G819A are associated with the weak D phenotype called weak D type 4 by Wagner et al.21

Analsis of Rh mRNA transcripts from Africans withRHDψ

mRNA transcripts were isolated from D-negative donors withRHDψ using either whole blood or erythroblasts cultured from CD34+ cells. An RHD-specific PCR gave a 645 bp product with cDNA prepared from a D-positive control, but the PCR did not give a product with cDNA prepared from a D-negative with RHDψ. An RHCE-specific PCR gave 715 bp products with all samples. We did not find a clone with anRHD insert, and an RHDψ sequence was not detected. These results suggest that there is no transcript fromRHDψ.

Screening D-negative donors for RHDexon 10 and intron 4 and for theRHDψ37 bp insert

All D-negative donors were tested by the multiplex PCR method designed to determine the presence of RHD exon 10 and intron 4. Intron 4 of RHCE was always detected as a control for successful amplification. Three patterns of reaction were apparent: presence of both RHD regions; absence of both RHD regions; and presence of RHD exon 10, but absence of RHD intron 4. Frequencies of these patterns are shown in Table 3 for each of the populations tested. Of the 82 D-negative black Africans tested (from South Africa, Zimbabwe, and Ghana), 67% had both regions ofRHD, 15% had RHD exon 10, and only 18% lackedRHD. The frequencies of the 3 genotypes were different in African Americans and mixed-race South Africans, with a substantially higher proportion having neither region of RHD (Table 3).

Results of testing for presence or absence ofRHD intron 4 and exon 10 and for the RHD exon 4 37 bp insert

| D Phenotype . | Population . | Number . | % . | Intron 4 . | Exon 10 . | Exon 4 . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal3-150 . | Insert . | |||||||

| Negative | Black South African | 29 | 20 | 69 | + | + | − | + |

| 6 | 21 | − | + | − | − | |||

| 3 | 10 | − | − | − | − | |||

| Negative | Zimbabwean | 19 | 13 | 68 | + | + | − | + |

| 2 | 11 | − | + | − | − | |||

| 4 | 21 | − | − | − | − | |||

| Negative | Ghanaian | 34 | 21 | 62 | + | + | − | + |

| 4 | 12 | − | + | − | − | |||

| 8 | 23 | − | − | − | − | |||

| 1 | 3 | + | + | + | − | |||

| Negative | African American | 54 | 13 | 24 | + | + | − | + |

| 12 | 22 | − | + | nt | nt | |||

| 29 | 54 | − | − | nt | nt | |||

| Negative | Mixed-race South African | 41 | 7 | 17 | + | + | − | + |

| 1 | 2 | − | + | nt | nt | |||

| 33 | 81 | − | − | nt | nt | |||

| Positive | Black South African | 95 | 83 | 87 | + | + | + | − |

| 12 | 13 | + | + | + | + | |||

| Positive | Caucasian | 13 | 13 | 100 | + | + | + | − |

| D Phenotype . | Population . | Number . | % . | Intron 4 . | Exon 10 . | Exon 4 . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal3-150 . | Insert . | |||||||

| Negative | Black South African | 29 | 20 | 69 | + | + | − | + |

| 6 | 21 | − | + | − | − | |||

| 3 | 10 | − | − | − | − | |||

| Negative | Zimbabwean | 19 | 13 | 68 | + | + | − | + |

| 2 | 11 | − | + | − | − | |||

| 4 | 21 | − | − | − | − | |||

| Negative | Ghanaian | 34 | 21 | 62 | + | + | − | + |

| 4 | 12 | − | + | − | − | |||

| 8 | 23 | − | − | − | − | |||

| 1 | 3 | + | + | + | − | |||

| Negative | African American | 54 | 13 | 24 | + | + | − | + |

| 12 | 22 | − | + | nt | nt | |||

| 29 | 54 | − | − | nt | nt | |||

| Negative | Mixed-race South African | 41 | 7 | 17 | + | + | − | + |

| 1 | 2 | − | + | nt | nt | |||

| 33 | 81 | − | − | nt | nt | |||

| Positive | Black South African | 95 | 83 | 87 | + | + | + | − |

| 12 | 13 | + | + | + | + | |||

| Positive | Caucasian | 13 | 13 | 100 | + | + | + | − |

Indicates that the 37 bp insert was not detected. TheRHCE intron 4 was detected in all samples.

Of 75 D-negative samples from people of African origin with RHD(including African Americans and mixed-race South Africans), 74 had the exon 4 37 bp insert (Table 3, Figure2). None of these 74 had normal RHDexon 4. These individuals must be homozygous for RHDψ,hemizygous for RHDψ, or heterozygous for RHDψ and the grossly abnormal RHD-CE-Ds gene associated with VS+ V– phenotype. Further investigation of the Ghanaian sample with RHD exon 4 (without a 37 bp insert), intron 4, and exon 10 has not been possible.

Agarose gel showing results of PCR screening test for the 37 bp RHD exon 4 insert with samples from black South Africans.

Agarose gel showing results of PCR screening test for the 37 bp RHD exon 4 insert with samples from black South Africans.

PCR-based tests on selected donors with sequence-specific primers revealed that those donors with RHD exon 10 and intron 4 also had RHD exons 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 9, suggesting the presence of grossly intact RHD. Red cells of all donors with RHDexon 10, but without RHD intron 4, were C+ and VS+; almost all were also V–. In addition to RHD exon 10, donors of this type had RHD exon 9 and a hybrid exon 3 comprising a 5′ end derived from RHD and a 3′ end derived fromRHCE. This suggests that these donors have the RHD-CE-Dgene associated with the (C)ces(r'S) complex.10 This gene will be referred to as RHD-CE-Ds. Selected donors with neither exon 10 nor intron 4 of RHD also lacked RHD exons 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 9, suggesting homozygosity for an RHD deletion.

Fifty-two of the 74 D-negative red cell samples with RHD (and with the 37 bp insert) in the 5 populations were D– C– c+ E– e+ VS– (probable genotype ce/ce). Of the remaining 22, 11 were D– C– c+ E– e+ VS+ V+, and 11 were D– C+ c+ E– e+ VS+ V–. These 22 were all heterozygous for C733G in exon 5 of RHCE and so had probable genotypes ofce/ces andce/(C)ces, respectively.20

Screening for RHDψ in random black South African blood donors

Ninety-eight random samples from black South Africans, consisting of 95 D-positive samples and 3 D-negative samples, were tested forRHDψ. Of the 98, 14 had RHDψ. This gives an approximate RHDψ gene frequency of 0.0714. This figure is based on the assumption that 1 of the D-negative donors is hemizygous, not homozygous, for RHDψ. The other randomly selected D-negative donor with RHDψ is VS+ V– with theRHD-CE-Ds gene, and the donor is assumed to be heterozygous for RHDψ.

Serological confirmation that the donors tested were D-negative

The donors used in this study were random D-negatives, as determined by the routine methods of the relevant transfusion services. In addition, their red cells gave negative results, by an antiglobulin test, with 2 alloanti-D reagents that react with all known partial D antigens and weak D antigens (with the exception of the extremely weak form of D known as Del). Several red cell samples from donors with RHDψ were tested with alloanti-D by an adsorption and elution technique that would be expected to detect a very weak D antigen. No anti-D could be detected in the eluate.

Of 5 African women who had produced anti-D, 4 had RHDψ, and the other had no RHD. This provides further evidence that these Africans with RHDψ are truly D-negative. One of the anti-D antibodies from a D-negative Ghanaian woman with RHDψ caused HDN, which required exchange transfusion.

A pregnant black English woman with anti-D had RHDψ. Testing of DNA derived from amniocytes obtained by amniocentesis showed that her fetus had RHDψ plus RHD with a normal exon 4. The fetus is, therefore, almost certainly D-positive and at risk from HDN.

A new PCR-based test for predicting D phenotype from genomic DNA

We have developed a new multiplex PCR-based test for detectingRHD, RHDψ, and the C and c alleles ofRHCE. Examples of the results are shown in Figure3. RHD and RHDψ give rise to 498 bp and 535 bp products, respectively, from RHD intron 4 exon 4. Because of the small difference in size between these 2 products, primers specific for the 37 bp insert in RHDψ were incorporated, and they gave rise to a 250 bp product whenRHDψ was present. Both genes produce a 95 bp product fromRHD exon 7. In addition, primers recognizing aC-specific sequence in RHCE intron 2 amplify a 320 bp product when a C allele is present; primers recognizing ac-specific sequence in RHCE exon 2 amplify a 177 bp product when a c allele is present.

Polyacrylamide gel showing results with multiplex PCR method for predicting D and C/c phenotype and for detecting the presence of RHDψ.

Polyacrylamide gel showing results with multiplex PCR method for predicting D and C/c phenotype and for detecting the presence of RHDψ.

Discussion

The D-negative phenotype of the Rh blood group system is generally considered to result, almost invariably, from homozygosity for a deletion of the D gene, RHD. Although this is true in Caucasians, it is certainly not the case in Africans. We have found that about two-thirds of D-negative Africans have an inactiveRHD gene. This pseudogene (RHDψ) has a 37 bp insert in exon 4, which may introduce a reading frameshift and premature termination of translation and a translation stop codon in exon 6. Of the remaining one-third of African D-negative donors, about half appear to be homozygous for an RHD deletion and about half have theRHD-CE-Ds hybrid gene characteristic of the(C)ces haplotype that produces c, VS, and abnormal C and e, but no D. In D-negative African Americans and South African people of mixed race (Coloured), the same 3 genetic backgrounds are present, but 24% of African Americans and 17% of South African donors of mixed race have RHDψ, and 54% of African Americans and 81% of South African donors of mixed race have no RHD.

The most common D-negative Rh haplotype in Africans is RHDψwith the ce allele of RHCE, although RHDψmight also be occasionally associated withces. The 37 bp insert in exon 4 ofRHDψ is a duplication of a sequence spanning the boundary of intron 3 and exon 4. This insert may introduce a reading frame shift and a translation stop codon at position 210. However, the duplication introduces another potential splice site at the 3′ end of the inserted intronic sequence in exon 4 (shown double-underlined in Figure1). If splicing occurred at this second splice site, the sequence of exon 4 would not be changed and could be translated normally. No RhD protein would be expected, however, because another stop codon is present in exon 6 of the gene. RHD mRNA was not detected in D-negative individuals with RHDψ, despite the presence ofRHCE transcripts. mRNA transcripts containing premature termination codons are often rapidly degraded as a result of nonsense-mediated mRNA decay.24

The initial report of the molecular basis for the Rh D-negative phenotype5 was followed by the publication of a number of PCR-based tests for predicting D phenotype from genomic DNA.25 Such techniques have proved valuable for predicting the D phenotype of fetuses of women with anti-D antibodies in order to assist in assessing the likelihood of HDN and in managing the pregnancy. Fetal DNA is usually derived from amniocytes obtained by amniocentesis or from chorionic villus samples. Antenatal administration of prophylactic anti-D immunoglobulin at around 28 weeks of gestation to all pregnant D-negative women is an enormous drain on stocks of anti-D immunoglobulin. About 40% of the fetuses of D-negative Caucasian women would be expected to be D-negative, yet these women still receive antenatal immunoglobulin prophylaxis. Less invasive PCR-based tests using maternal plasma are currently being developed, and they may make it possible to test the fetal D phenotype of all D-negative pregnant women.18,19 26

All existing methods for predicting D phenotype from genomic DNA or mRNA are based on detecting the presence or absence of various regions of RHD and are unsuitable for testing African populations or any populations containing a substantial proportion of people with African ethnicity. We have devised a new test that detects the presence of RHDψ. This test incorporates a primer that specifically detects the presence of the 37 bp insert in RHDψ. In addition, the presence or absence of exon 7 and intron 4 of RHDand RHDψ are detected. This test would give either an unusual result or a D-positive result with genes encoding partial D antigens. The multiplex PCR test also includes primers that determine the presence of C and c alleles of RHCE. This will be particularly informative because the D-negative phenotype is not usually associated with C expression. Most inactive RHD genes, with the exception of RHDψ, are in ciswith a C allele of RHCE. Typing the fetus for the C allele is also valuable because anti-G may be responsible for HDN.27

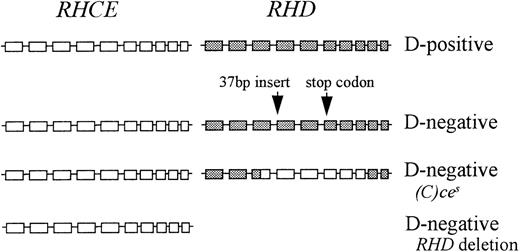

The Rh proteins exist in the red cell membrane as part of a complex of proteins and glycoproteins. In most people this complex comprises RhCcEe polypeptide, RhD polypeptide, and the Rh-associated glycoprotein. This complex may also be associated, in the membrane, with LW glycoprotein and CD47 and possibly with Duffy glycoprotein and glycophorin B.28 In D-negatives, the RhD polypeptide is not present in the Rh membrane complex. There are 3 common genetic mechanisms responsible for the D-negative phenotype: deletion of RHD, a pseudogene RHD containing a 37 bp insert and 1 or 2 stop codons, and a hybridRHD-CE-Ds gene that probably produces an abnormal C antigen but does not produce a D antigen (Figure4). Functions of the Rh proteins are not known, so it is difficult to speculate on the evolutionary significance of the D-negative phenotype and, therefore, why 3 different mechanisms have evolved to create this phenotype. D-negative fetuses have an advantage in D-negative mothers as they are not destroyed by maternal anti-D. Consequently, HDN may provide a selection pressure in favor of inactive RHD, which has driven the evolution of the D polymorphism with different genetic backgrounds in different ethnic groups. It is unlikely, however, that HDN alone has provided the selective pressure responsible for the high prevalence of D negativity.

Representation of the genomic organization of the D-positive haplotype and 3 D-negative haplotypes in Africans.

□ indicates RHCE exon; ▪, RHD exon.

Representation of the genomic organization of the D-positive haplotype and 3 D-negative haplotypes in Africans.

□ indicates RHCE exon; ▪, RHD exon.

Acknowledgment

We are grateful to the Western Province Blood Transfusion Service for obtaining blood samples from mixed-race donors in South Africa.

Supported by a grant from DiaMed AG, Cressier-sur-Morat, Switzerland.

Reprints:Geoff Daniels, Bristol Institute for Transfusion Sciences, Southmead Road, Bristol BS10 5ND, England; e-mail:geoff.daniels@nbs.nhs.uk.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal