Abstract

Cathepsin G is a neutral serine protease that is highly expressed at the promyelocyte stage of myeloid development. We have developed a homologous recombination strategy to create a loss-of-function mutation for murine cathepsin G. Bone marrow derived from mice homozygous for this mutation had no detectable cathepsin G protein or activity, indicating that no other protease in bone marrow cells has the same specificity. Hematopoiesis in cathepsin G−/− mice is normal, and the mice have no overt abnormalities in blood clotting. Neutrophils derived from cathepsin G−/− mice have normal morphology and azurophil granule composition; these neutrophils also display normal phagocytosis and superoxide production and have normal chemotactic responses to C5a, fMLP, and interleukin-8. Although cathepsin G has previously shown to have broad spectrum antibiotic properties, challenges of mice with Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, or Escherichia coli yielded survivals that were not different from those of wild-type animals. In sum, cathepsin G−/− neutrophils have no obvious defects in function; either cathepsin G is not required for any of these normal neutrophil functions or related azurophil granule proteases with different specificities (ie, neutrophil elastase, proteinase 3, azurocidin, and/or others) can substitute for it in vivo.

CATHEPSIN G IS A neutral serine protease that is expressed and synthesized at the promyelocyte stage of development and is packaged in the azurophil (primary) granules.1,2 The amino acid composition and crystal structure of cathepsin G are known.3-5 The human and murine cathepsin G genes have been cloned6,7 and reside within a cluster of granule-related serine proteases on syntenic regions of human and mouse chromosomes 14.8-13 The highly related serine proteases known as neutrophil elastase (NE), azurocidin, and proteinase 3 are also expressed specifically in promyelocytes and packaged in azurophil granules; these 3 genes are located in a tight cluster on human chromosome 19 pter.14 The human and mouse cathepsin G genes are highly related and are expressed in identical fashion6,7,15; therefore, these genes are thought to be true orthologues of one another. Cathepsin G has chymotrypsin-like specificity, preferring to cleave at Phe in the P1 position16; a large number of potential substrates for cathepsin G have been identified (discussed below). Although cathepsin G is found in the azurophil granules of neutrophils, this enzyme has also been found on the surface of neutrophils after degranulation.17,18 Recent studies have suggested that inhibitors of cathepsin G (α-1 antichymotrypsin and/or specific antibodies directed against cathepsin G) can diminish the ability of neutrophils to respond to a variety of chemotactic signals, suggesting that cell surface-bound cathepsin G may play a role in this process.19 20

Cathepsin G has been proposed to play a role in blood clotting, because it cleaves and inactivates several clotting factors,21-26because it can cleave and potentially modulate the function of the thrombin receptor,27-29 and because it can activate platelets in vitro.30-38 Tight contact is thought to be required between neutrophils and platelets for platelet activation to occur33 34; cleavage of the thrombin receptor or thrombin receptor-like proteins could potentially play a role in this process.

Cathepsin G has been proposed to play a role in neutrophil responses against a variety of bacteria. Purified cathepsin G has been shown to inhibit the growth of several organisms, including Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Neisseria gonorrhea; it also displays toxic properties against Eimeria tenella sporozoites, Capnocytophaga, and Listeria monocytogenes.39-45 The enzymatic activity of cathepsin G is not required for its antibacterial activities39,46-48; in fact, 3 peptides derived from cathepsin G (IIGGR [aa 1-5], HPQYNQR [aa 77-83], and RPGTLCTVAGWGRVSMRRGT [aa 117-136]) have direct antimicrobial properties.47 48 The precise mechanisms by which these peptides cause bacterial death are currently unknown.

Cathepsin G has a number of potential substrates and activities that are difficult to classify, including the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II,49 the activation and damage of cultured airway epithelial cells,50 the stimulation of secretion by airway gland serous cells,51 the induction of transendothelial albumin flux,52 and the processing of NF-kB (p65) in vitro.53 It is not yet clear that any of these activities represent physiologic roles of this enzyme.

Finally, cathepsin G has been proposed to play an important role in tissue remodeling at sites of wounding or tissue injury. Cathepsin G has been shown to cleave and inactivate the neutrophil chemoattractants tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα),54 interleukin-1 (IL-1),55 and IL-8.56 In addition, cathepsin G has been shown to cleave several matrix components, including collagen, fibronectin, cartilage proteoglycans, and elastin.57-64 For this reason, we recently examined the ability of cathepsin G-deficient mice (the same mice described in this study) to heal incisional wounds and found that these animals have reduced tensile strength of their healing wounds at 7 days. This defect is resolved by 10 days.65 Cathepsin G-deficient mice display excessive neutrophilic inflammation at sites of wounding, which may be caused by increased neutrophil chemoattractant activity in the wound fluid.65 These observations suggest that cathepsin G may be involved in degrading one or more soluble mediators in the wound milieu that are important for the early phases of neutrophil migration into the wound. However, we could not rule out an autonomous defect of cathepsin G-deficient neutrophils that might contribute to the abnormal wound healing.

In this report, we fully describe mice that possess a null mutation of cathepsin G. Cathepsin G−/− animals have no detectable defects in myeloid development or neutrophil function, suggesting that either cathepsin G is not required for these functions or that related proteases can substitute for the functions of cathepsin G in some circumstances.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Production of the targeting construct.

A 3.7-kb Bgl II genomic fragment containing the 3′ part of exon 4 through the 3′ flank of the murine cathepsin G gene was subcloned into the MJK-KO vector downstream from the PGK-neo cassette. A 1.6-kb HindIII/Pst I fragment containing 5′ genomic flanking sequence, exons 1 and 2, introns 1 and 2, and the 5′ part of exon 3 was purified from a pUC 9 vector and subcloned into pGEM7. This plasmid was then cut with Bgl II andXho I; the resulting Bgl II/Xho I fragment was subcloned upstream from the PGK-neo cassette and downstream from the HSV-TK cassette of the MJK-KO vector.66 Therefore, a 393-bpPst I-Bgl II fragment containing the 3′ end of exon 3, intron 3, and the 5′ end of exon 4 was removed and replaced with a standard PGK-neo cassette in the reverse orientation. This deletion removes the region encoding aa 92-164 of the cathepsin G protein (numbering from the initiation codon).

Electroporation, selection, and screening of embryonic stem (ES) cells.

Early passage RW4 ES cells (129/SvJ) were maintained on feeder layers of murine embryonic fibroblasts in the presence of 103 U/mL leukocyte inhibitory factor. ES cells were transfected and selected, and G418-resistant clones were identified by Southern blotting using probe A (see Fig 1A). Recombinant clones were confirmed using a probe specific for PGK-neo (probe B).

Production of mutant mice.

C57Bl/6J blastocysts were microinjected with 10 to 12 ES cells from 3 independent targeted clones and implanted into pseudopregnant Swiss Webster foster females. Chimeric male progeny with greater than 60% agouti fur were mated with C57Bl/6J females, and their progeny were screened by Southern blot analysis (with probe A) for transmission of the targeted allele. Heterozygotes were interbred to produce homozygous mutant mice derived from 2 of the independently targeted ES clones (no. 11 and 76). Both lines were phenotypically identical. Chimeric males from line 76 were also bred to 129/SvJ females to obtain cathepsin G-deficient mice in a pure 129/SvJ background. Mice were maintained in a specific virus free (SVAF) barrier facility at all times.

S1 nuclease protection assays.

Total cellular RNA was prepared and analyzed by S1 nuclease protection, as previously described.67 The gene-specific probes for murine granzyme B,2 murine cathepsin G,7 and murine β2-microglobulin2 have been described previously. The probe for murine mast cell chymase-2 (mMCP-2) RNA was obtained by polymerase chain reaction (PCR); the forward primer was located in IVS-4 (TTCATCTCCcathepsin GTTCTCAAGC) and the reverse primer in exon 5 (AGACTTGATGCAGGATGAGA); and the PCR product was 489 bp in length. Correctly processed exon 5 mMCP-2 mRNA protects a probe fragment of 235 nucleotides from S1 nuclease digestion. Autoradiograms were exposed for 24 to 72 hours.

Western analysis.

Total proteins were prepared from approximately 2 × 107 bone marrow cells by sonicating the cells in 200 μL of extraction buffer (1 mol/L NaCl, 25 mmol/L Tris 7.5, 0.1% Triton X-100); protein was quantified using the Bio-Rad Protein Assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Equal quantities of total proteins were loaded onto 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gels, transferred to nitrocellulose, and analyzed with a standard Western blotting technique using a rabbit antiserum directed against a murine cathepsin G-derived peptide (aa 152-165 numbered from the initiation codon: CANRFQFYNSQTQI), followed by detection with chemiluminescence (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL).

Determination of cathepsin G and neutrophil elastase activity.

Total bone marrow cells were extracted in extraction buffer as described above and normalized for total protein context using the Bio-Rad assay. Cathepsin G activity was measured using the peptide substrate N-Succinyl-Ala-Ala-Pro-Phe-pNA (Sigma, St Louis, MO) and neutrophil elastase activity with the substrate N-Methoxysuccinyl-Ala-Ala-Pro-Val-pNA, as previously described.68

Generation of bone marrow-derived mast cells.

Mast cells were generated by culturing murine bone marrow cells for 3 weeks in enriched media (RPMI 1640 containing 0.1 mmol/L nonessential amino acids, 2 mmol/L L-glutamine, 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, 100 U/mL penicillin, 10 μg/mL gentamicin, and 50 mmol/L 2-mercaptoethanol) supplemented with 50% WEHI-3 cell conditioned media (WCM), as previously described.69 After 3 weeks, the cells were cultured for an additional 72 hours in 50% WCM/50% enriched media supplemented with 100 U/mL recombinant murine IL-10 (Amersham). RNA was then extracted from the cells and analyzed using S1 nuclease protection assays. These preparations yielded greater than 90% mast cells as judged by light microscopic criteria.

Isolation of bone marrow-derived neutrophils.

Bone marrow was harvested using Hank's balanced salt solution (HBSS; 138 mmol/L NaCI, 5.4 mmol/L KCl, 0.4 mmol/L KH2PO4, 0.2 mmol/L Na2HPO4, 4.1 mmol/L NaHCO3, 5.5 mmol/L glucose) containing 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Neutrophils were purified from the bone marrow preparations using a discontinuous Ficoll gradient (Histopaque 1119; Sigma). Cells were then washed twice with HBSS containing 1% BSA. Neutrophil purity was consistently 75% to 85%, as assessed by light microscopy of Wright-Giemsa–stained cytospins.

Phagocytosis.

In vitro, 5 × 104 neutrophils in 100 μL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; define) were mixed with 10 μL of a 1:5 dilution of 0.9-μm diameter fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled latex beads (Poly Sciences, Inc, Warrington, PA) and incubated for 1 hour at 37°C. Cells were then washed with media, trypsin-EDTA was added, and the cells were incubated at 37°C for 10 minutes. Cells were then layered over 4°C fetal calf serum and spun at 1,500 rpm for 5 minutes to remove uningested beads. After washing, the cells were fixed with 1.0% paraformaldehyde in PBS and observed under a fluorescent microscope.

In vivo, 2 mL of zymosan (Sigma) was injected intraperitoneally. Total intraperitoneal cells were harvested after 4 hours by injecting 10 mL of PBS and then withdrawing 7 to 9 mL of fluid for analysis. Cytospin preparation of cells were made and stained using Wright-Giemsa stain.

Superoxide production.

Purified bone marrow-derived neutrophils were resuspended in HBSS (with 1.3 mmol/L CaCl2 and 0.4 mmol/L MgSO4) and added to tubes containing 0.2 mmol/L cytochrome C (Sigma) and 0, 5, 10, or 25 ng/mL phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA; Sigma) or containing cytochrome C plus 300 U/mL superoxide dismutase (SOD; Sigma) with 0, 5, 10, or 25 ng/mL PMA. The cells were incubated for 20 minutes at 37°C in 5% CO2 and then centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 2 minutes. Supernatants were assayed at OD550. The amount of superoxide produced was calculated using the following formula: (ΔOD × 100)/21.1 = micromoles of O2− = (nanomoles of O2−/mL)/(PMNs/mL/time) = nanomoles of O2−/PMNs/time.

Chemotaxis.

Optimal concentrations of several chemotactic agents were defined using bone marrow-derived neutrophils, including fMLP (10−4mol/L; Sigma), zymosan-activated rat serum (7%), and recombinant human IL-8 (rhIL-8; 250 ng/mL; Amersham); these optimal concentrations were used for all further experiments.70Chemotactic agents were suspended in the bottom wells of micro-chemotaxis chambers. The bottom chamber was covered with 2-mm membrane filters, and 150,000 bone marrow-derived neutrophils (in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium [DMEM]/0.1% human serum albumin) derived from wild-type or cathepsin G-deficient mice (all in the pure 129/SvJ strain) were suspended in the top wells. After incubation for 75 minutes at 37°C in 5% CO2, the membranes were fixed, stained with Leukostat (Sigma), and placed on glass slides. Cells from the top chamber were removed with a wiper blade. Fifteen fields were counted at 400× magnification. Each experiment was performed in triplicate. Media alone was used as a negative control and subtracted from total counted cells to yield net neutrophil movement.

Chemoattractant-induced calcium influx.

Bone marrow-derived neutrophils were loaded with the calcium sensitive dye Fluo-3 (9 μmol/L acetoxymethyl ester Fluo-3; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for 30 minutes at room temperature in HBSS without calcium or magnesium. Cells were stained with phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti–Gr-1 antibody (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA), washed, and then resuspended in HEPES buffer (137 mmol/L NaCl, 5 mmol/L KCl, 1 mmol/L Na2HPO4, 5 mmol/L glucose, 1 mmol/L CaCl2, 0.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 0.1% BSA, and 10 mmol/L HEPES, pH 7.4). Antifluorescein antibody was added (per the manufacturer's recommendation) to quench extracellular Fluo-3 signals. The indicated agonist was added and cellular Fluo-3 fluorescence was measured continuously for 90 seconds using a Coulter ESP flow cytometer (Coulter, Hialeah, FL), as previously described.71

In vivo bacterial clearance.

All in vivo assays were performed in mice having a pure 129/SvJ background. S aureus was grown in tryptic soy broth (TSB) and passaged twice in 129/SvJ mice before use. Varying doses of S aureus were injected intraperitoneally (IP) into 129/SvJ mice to define the LD50, which was approximately 2.5 × 108colony-forming units (CFU). Eight cathepsin G+/+ (5 male and 3 female) and 9 cathepsin G−/− (5 male and 4 female) 10-week-old mice were injected IP with 108 CFU S aureus and observed for 15 days. Deaths were recorded and analyzed.

Klebsiella pneumoniae (KPA strain) was grown in TSB and passaged once in 129/SvJ mice before use. Varying doses ofK pneumoniae were injected IP into wild-type 129/SvJ mice, and the LD50 was determined to be between 5 × 105 CFU and 1 × 106 CFU. Fourteen cathepsin G+/+ and 15 cathepsin G−/− 12-week-old male mice were injected IP with 1 × 106 CFU of K pneumoniae. Deaths were recorded and analyzed.

E coli (K1) was grown in TSB and passaged twice in 129/SvJ mice before use. Varying doses of E coli were injected IP into wild-type 129/SvJ mice to determine the LD50, which was 3 × 104 CFU. This dose of bacteria was then injected IP to 13 wild-type mice, 12 cathepsin G−/− mice, and 12 NE−/− mice. Deaths were recorded and analyzed.

In vitro microbicidal assays.

The in vitro bactericidal activities of cathepsin G and NE were quantified as described.45K pneumoniae, E coli, and S aureus were grown in TSB at 37°C and washed twice with PBS. Mid-log phase bacteria (105) were incubated in the absence or presence of purified human NE or cathepsin G (5 μg; Elastin Products Co, Owensville, MO) in a total volume of 100 μL of 10 mmol/L sodium phosphate containing 1% (vol/vol) TSB at 37°C for 4 hours. Serial dilutions were then spread on agarose plates and the number of CFUs was determined after overnight incubation. At the time of each assay, cathepsin G and NE activities were confirmed using the spectrophotometric method of peptide substrate cleavage described above.

RESULTS

Targeting of the cathepsin G gene in ES cells and production of mutant mice.

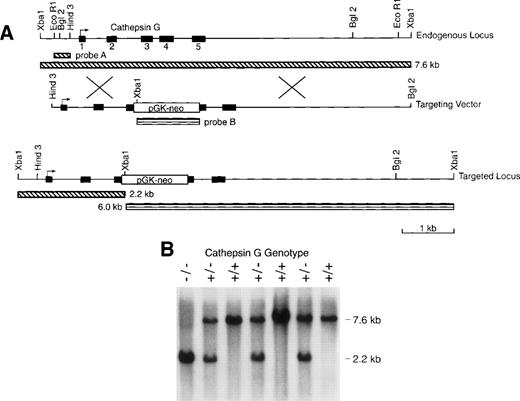

We electroporated RW4 ES cells (129/SvJ) with our cathepsin G targeting vector (Fig 1). Three homologous recombinants were identified (using Southern blotting with external probe A) of 192 G418-resistant colonies screened from 2 independent transfections. After injection of C57Bl/6 blastocysts, all 3 of these ES clones gave rise to highly chimeric males that were then mated to C56Bl/6 females to obtain germline transmission of the mutant cathepsin G allele. Chimeric males were also mated to 129/SvJ females to obtain germline transmission in pure 129/SvJ mice. Figure 1B is a Southern blot analysis of genomic tail DNA of progeny produced from a cross of cathepsin G+/− animals. Genomic DNA was digested with Xba I and hybridized with probe A to show bands representing the wild-type (7.6 kb) and mutant (2.6 kb) alleles. The heterozygous matings produced wild-type, heterozygous, and homozygous mice at expected ratios (+/+:+/−:−/−= 30:55:31). Cathepsin G−/− mice develop normally and are fertile. Mice were evaluated from 2 independently targeted ES clones and both had the same phenotype (data not shown).

The cathepsin G (CG) locus and targeting strategy. (A) The structures of the murine cathepsin G gene and the targeting vector used to create homologous recombinants are shown. The PGK-neo cassette was inserted in the antisense orientation with respect to the cathepsin G gene. The structure of the targeted locus and the sizes of fragments detected by probe A (which is completely external to the targeting construct) and probe B (the PGK-neo cassette) are shown. (B) Southern blot analysis of tail DNA from the progeny of a cross between cathepsin G+/− animals. Genomic DNA was cleaved with Xba I and the blot was hybridized with probe A. The positions of the wild-type (7.6 kb) allele and the targeted (2.2 kb) allele are shown.

The cathepsin G (CG) locus and targeting strategy. (A) The structures of the murine cathepsin G gene and the targeting vector used to create homologous recombinants are shown. The PGK-neo cassette was inserted in the antisense orientation with respect to the cathepsin G gene. The structure of the targeted locus and the sizes of fragments detected by probe A (which is completely external to the targeting construct) and probe B (the PGK-neo cassette) are shown. (B) Southern blot analysis of tail DNA from the progeny of a cross between cathepsin G+/− animals. Genomic DNA was cleaved with Xba I and the blot was hybridized with probe A. The positions of the wild-type (7.6 kb) allele and the targeted (2.2 kb) allele are shown.

Cathepsin G−/− mice contain a null mutation for cathepsin G.

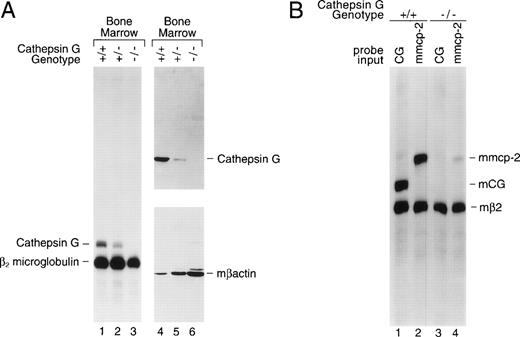

Bone marrow was harvested from cathepsin G+/+, +/−, and −/− mice and total cellular RNA was prepared for analysis by S1 nuclease protection. Figure 2A (left panel) is an S1 nuclease protection analysis of bone marrow cell RNA (lanes 1, 2, and 3). RNA samples (10 μg) were hybridized with specific probes for exon 5 of murine cathepsin G and for β2 microglobulin (mβ2M). Correctly processed murine cathepsin G exon 5 mRNA protects a probe fragment of 212 nt from S1 digestion, whereas mβ2M mRNA protects a fragment of 190 nt. Cathepsin G mRNA is present in the bone marrow of +/+ mice, is reduced in +/− mice, and is undetectable in the bone marrow of cathepsin G−/− mice (Fig 2A). The mβ2M signal is present in bone marrow RNA from all 3 mice and serves as an internal control for RNA quality and content.

The cathepsin G mutation eliminates cathepsin G mRNA and protein expression in the bone marrow of cathepsin G−/− mice. (A) Lanes 1 through 3 show an S1 nuclease protection analysis of cathepsin G and β2 microglobulin mRNAs in bone marrow samples derived from +/+, +/−, and −/− mice. In lanes 4 through 6, a Western blot was performed with a rabbit antimurine cathepsin G antibody prepared against a peptide from a unique region of the cathepsin G protein (see Materials and Methods). After hybridization and chemiluminescence, the blot was stripped and reprobed for the presence of β-actin to control for protein loading. (B) Analysis of mMCP-2 mRNA in cultured mast cells derived from the bone marrow of cathepsin G+/+ and −/− mice. An S1 nuclease protection assay was performed with probes for mouse β2 microglobulin and either mouse cathepsin G or mMCP-2, as indicated. The positions of probe fragments protected from S1 nuclease digestion by correctly spliced mcathepsin G and mMCP-2 are shown. Mast cell mRNA from cathepsin G+/+ animals contains easily detectable mcathepsin G mRNA. RNA derived from cathepsin G−/− mast cells shows no cathepsin G mRNA, as expected, and a 10-fold reduction in mMCP-2 mRNA levels.

The cathepsin G mutation eliminates cathepsin G mRNA and protein expression in the bone marrow of cathepsin G−/− mice. (A) Lanes 1 through 3 show an S1 nuclease protection analysis of cathepsin G and β2 microglobulin mRNAs in bone marrow samples derived from +/+, +/−, and −/− mice. In lanes 4 through 6, a Western blot was performed with a rabbit antimurine cathepsin G antibody prepared against a peptide from a unique region of the cathepsin G protein (see Materials and Methods). After hybridization and chemiluminescence, the blot was stripped and reprobed for the presence of β-actin to control for protein loading. (B) Analysis of mMCP-2 mRNA in cultured mast cells derived from the bone marrow of cathepsin G+/+ and −/− mice. An S1 nuclease protection assay was performed with probes for mouse β2 microglobulin and either mouse cathepsin G or mMCP-2, as indicated. The positions of probe fragments protected from S1 nuclease digestion by correctly spliced mcathepsin G and mMCP-2 are shown. Mast cell mRNA from cathepsin G+/+ animals contains easily detectable mcathepsin G mRNA. RNA derived from cathepsin G−/− mast cells shows no cathepsin G mRNA, as expected, and a 10-fold reduction in mMCP-2 mRNA levels.

Total protein extracts from cathepsin G+/+, +/−, and−/− bone marrows were analyzed by Western blotting (Fig2A, right panel); the blot was probed sequentially with a rabbit antimurine cathepsin G antibody and a rabbit antimurine β-actin antibody to control for protein loading. No cathepsin G protein (∼29 kb) is detected in the bone marrow of cathepsin G−/− mice.

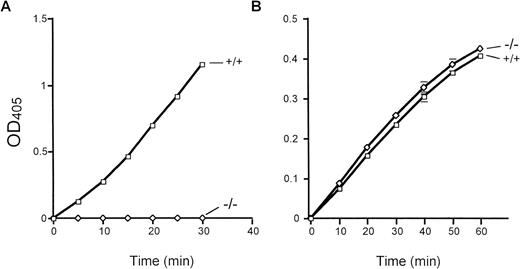

Total bone marrow extracts were evaluated for cathepsin G activity using the peptide substrate N-Succinyl-Ala-Ala-Pro-Phe-pNA. Importantly, equal amounts of human versus mouse bone marrow extracts contained virtually identical amounts of cathepsin G activity (data not shown). Marrow extracts derived from cathepsin G−/− mice have virtually no detectable cleavage of this peptide substrate (Fig 3A). Neutrophil elastase-deficient mice have normal levels of cathepsin G activity, as expected (data not shown). In contrast, cathepsin G−/− bone marrow extracts cleave the elastase-specific peptide substrate N-Methoxy Succinyl-Ala-Ala-Pro-Val-pNA as efficiently as wild-type marrow extracts, as expected (Fig 3B).

Cathepsin G and neutrophil elastase activities in cathepsin G-deficient mice. The activity of cathepsin G and neutrophil elastase was determined by the ability of total bone marrow protein extracts to cleave colorometric peptide substrates in vitro, as described in Materials and Methods. (A) A peptide substrate for cathepsin G (N-Succinyl-Ala-Ala-Pro-Phe-pNA) is used. Cathepsin G−/− mice have no detectable conversion of this substrate even after 30 minutes of incubation at 37°C. (B) The conversion of the neutrophil elastase-specific peptide (N-Methoxysuccinyl-Ala-Ala-Pro-Val-pNA) is shown. Wild-type and cathepsin G−/− mice have equivalent amounts of neutrophil elastase activity. These experiments were performed 3 times with identical results.

Cathepsin G and neutrophil elastase activities in cathepsin G-deficient mice. The activity of cathepsin G and neutrophil elastase was determined by the ability of total bone marrow protein extracts to cleave colorometric peptide substrates in vitro, as described in Materials and Methods. (A) A peptide substrate for cathepsin G (N-Succinyl-Ala-Ala-Pro-Phe-pNA) is used. Cathepsin G−/− mice have no detectable conversion of this substrate even after 30 minutes of incubation at 37°C. (B) The conversion of the neutrophil elastase-specific peptide (N-Methoxysuccinyl-Ala-Ala-Pro-Val-pNA) is shown. Wild-type and cathepsin G−/− mice have equivalent amounts of neutrophil elastase activity. These experiments were performed 3 times with identical results.

The cathepsin G mutation reduces expression of the downstream mMCP-2 gene.

Our laboratory has shown that the targeted disruption of the granzyme B gene (with a retained PGK-neo cassette) also disrupts expression of the downstream granzymes C, D, F, and G in adherent lymphokine-activated killer (AdLAK) cells derived from granzyme B−/− mice. This phenomenon is known as the neighborhood effect and is thought to be caused by the retained PGK-neo cassette in the mutant locus.72-75

The targeted mutation of the cathepsin G gene minimally alters the expression of the upstream granzymes (B, C, D, and F) in activated cytotoxic T lymphocytes and AdLAK cells.10 To determine whether the mutation in the cathepsin G gene affects expression of downstream murine mast cell chymase genes,10-13,76,77 we developed PCR-based detection methods for the mMCP-1, -2, -4, and -5 genes and screened for their presence (using PCR) on a bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) that was known to contain the cathepsin G gene.10 Only mMCP-2, a chymase known to be expressed in mucosal mast cells,76 was present on this BAC clone, mapping approximately 30 kb downstream from the cathepsin G gene. Mast cells were cultivated from bone marrow cells that had been incubated for 3 weeks in WCM and then stimulated for 72 hours in conditioned media containing murine rIL-10 (100 U/mL).76,77 An S1 probe specific for mMCP-2 was developed and used to analyze these mast cell mRNA samples (Fig 2B). Cathepsin G was expressed in cathepsin G+/+ mast cells, but not in cathepsin G−/− mast cells, as expected (lanes 1 and 3, respectively). However, whereas mMCP-2 is expressed in cathepsin G+/+ mast cells, there is a 10-fold reduction (as determined by phosphorimaging) of mMCP-2 mRNA levels in cathepsin G−/− mast cell mRNA (lanes 2 and 4, respectively). Although bone marrow samples and cultured mast cells appear to have nearly equivalent levels of cathepsin G mRNA, the level of cathepsin G mRNA per expressing cell may be much higher in promyelocytes, because these are the only bone marrow cells that contain detectable cathepsin G mRNA and because they comprise only 1% to 2% of total bone marrow cells.2 7

Hematopoiesis, lymphopoiesis, and myeloid granule development are normal in cathepsin G−/− mice.

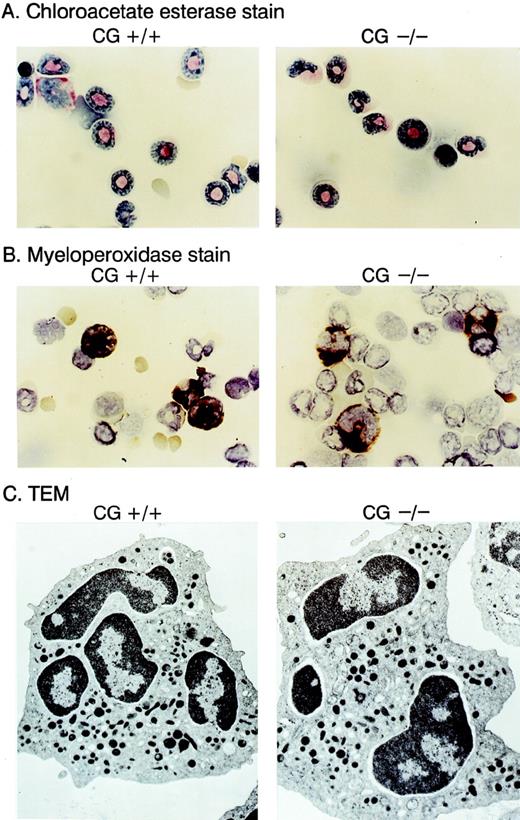

We compared the hematopoietic development of multiple cathepsin G+/+ and cathepsin G−/− mice derived from 2 different ES cell lines. Complete blood counts and differentials showed no differences between cathepsin G+/+ and cathepsin G−/− animals (n = 8, data not shown). Cytospins of bone marrow cells from cathepsin G+/+ and cathepsin G−/− mice were Wright-Giemsa stained and evaluated for the presence of myeloperoxidase and chloroacetate esterase activity; no clear differences were detected (Fig 4A and B). Transmission electron micrography of bone marrow-derived neutrophils from cathepsin G−/− mice showed normal numbers of electron-dense (azurophil) granules (Fig 4C) and normal neutrophil morphology. The thymic and splenic tissues of cathepsin G−/− mice were evaluated by flow cytometry, using the markers for CD3, CD4, CD8, B220, and NK1.1, as previously described.66 Normal numbers and proportions of all lymphoid compartments were present in both organs, as well as in the peripheral blood (data not shown). Similarly, normal numbers of Gr-1–positive and CD11b-positive cells were present in the bone marrow and peripheral blood of the mutant mice (data not shown).

Morphology of neutrophils derived from cathepsin G-deficient animals. Bone marrow cells were stained with choracetate esterase (A) or myeloperoxidase stains (B) using conditions recommended by the manufacturer (Sigma). The reddish-pink stain in (A) represents chloracetate esterase activity, and the dark brown stain in (B) represents myeloperoxidase activity. Transmission electron microscopic (TEM) images of bone marrow derived neutrophils are shown in (C). Note that cathepsin G−/− neutrophils have equal numbers of electron-dense granules and normal morphology.

Morphology of neutrophils derived from cathepsin G-deficient animals. Bone marrow cells were stained with choracetate esterase (A) or myeloperoxidase stains (B) using conditions recommended by the manufacturer (Sigma). The reddish-pink stain in (A) represents chloracetate esterase activity, and the dark brown stain in (B) represents myeloperoxidase activity. Transmission electron microscopic (TEM) images of bone marrow derived neutrophils are shown in (C). Note that cathepsin G−/− neutrophils have equal numbers of electron-dense granules and normal morphology.

Normal hemostasis in cathepsin G−/− mice.

Cathepsin G−/− mice do not hemorrhage at birth and clot normally when tailed or subjected to retroorbital bleeding. The bleeding time of cathepsin G−/− mice is 3.9 ± 2 minutes (n = 6), a value that is not different from the bleeding times of wild-type littermate controls (4.2 ± 1.5 minutes, n = 6). Histopathologic examination of the spleens, livers, kidneys, and lungs from 1- to 2-year-old cathepsin G−/− mice showed no evidence of microthrombosis or chronic organ damage of any kind (data not shown).

Phagocytosis and superoxide production are normal in cathepsin G−/− neutrophils.

Neutrophils isolated from bone marrow were incubated with FITC-labeled latex beads and observed under a fluorescent microscope. At least 98% of cathepsin G+/+ and cathepsin G−/− neutrophils engulfed ≥10 beads. In addition, cathepsin G+/+ and cathepsin G−/− mice were injected IP with 2 mL of zymosan. Four hours later, cells were harvested and cytospins were made. Again, at least 98% of cathepsin G+/+ and cathepsin G−/− neutrophils had engulfed at least 10 zymosan particles.

α-1 antichymotrypsin, a serpin that inhibits cathepsin G, has been shown to inhibit neutrophil superoxide production in vitro78 79; we therefore asked whether cathepsin G was required for this response. Bone marrow neutrophils from cathepsin G+/+ and cathepsin G−/− mice were stimulated with 0 to 25 μg/mL PMA, and cells were analyzed for superoxide production. Cathepsin G deficiency had no significant effect on the production of superoxide at these concentrations of PMA (data not shown).

Cathepsin G−/− neutrophils have normal in vitro and in vivo chemotaxis.

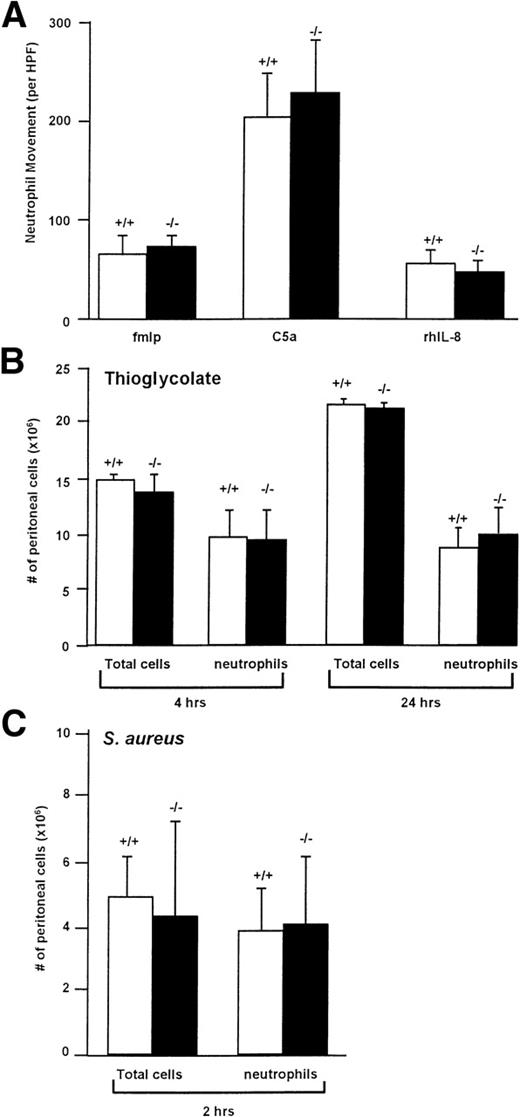

Membrane-bound cathepsin G has been suggested to play a role in chemotaxis, although the mechanism by which it functions in this setting is unknown. We therefore examined the in vitro chemotaxis of cathepsin G−/− neutrophils using a Boyden chamber using optimal concentrations of C5a (7% zymosan-activated serum), fMLP (10−4 mol/L; we confirmed that a much higher concentration of fMLP is required for the optimal chemotaxis of murine neutrophils [10−4 mol/L] compared with human neutrophils [10−7 mol/L]70), or recombinant human IL-8 (250 μg/mL), as shown in Fig 5A. There was no significant reduction in the chemotaxis of cathepsin G−/− neutrophils towards any of these reagents.

Cathepsin G−/− neutrophils have normal chemotaxis towards a variety of stimuli in vitro and in vivo. (A) Cathepsin G−/− neutrophils have normal chemotaxis in vitro. Bone marrow-derived neutrophils from wild-type (+/+) and cathepsin G-deficient mice (−/−) were added to the top of a modified micro-Boyden chamber with the chemoattractant on the bottom well. Maximally effective concentrations of fMLP (10−4 mol/L), C5a (7% zymosan activated serum), and rhIL-8 (250 ng/mL) were used. Net neutrophil movement per high power field (HPF) is defined as total neutrophils minus neutrophils migrating towards the media control (between 11 and 15 for different experiments). The data represent the mean from 4 individual mice per group each performed in triplicate. Bars represent standard deviations. (B) Quantitation of the total cells and neutrophils in peritoneal lavage fluid from thioglycolate-treated mice. Mice were injected with 2 mL of thioglycolate IP, and, at the indicated times, peritoneal cells were harvested by lavage and quantified. Cathepsin G +/+ and −/− mice demonstrate nearly identical numbers of total cells and neutrophils in the peritoneal harvests. This experiment was repeated 3 times with similar results. (C) Inflammation induced by IP injection of S aureus is not altered in cathepsin G−/− mice. S aureus (108CFU) was injected into the peritoneal cavities of 3 cathepsin G+/+ or −/− mice, and peritoneal lavage was performed 2 hours later. There is no significant difference between the total cells or the number of neutrophils harvested from cathepsin G+/+ or −/− mice. This experiment was repeated twice with similar results.

Cathepsin G−/− neutrophils have normal chemotaxis towards a variety of stimuli in vitro and in vivo. (A) Cathepsin G−/− neutrophils have normal chemotaxis in vitro. Bone marrow-derived neutrophils from wild-type (+/+) and cathepsin G-deficient mice (−/−) were added to the top of a modified micro-Boyden chamber with the chemoattractant on the bottom well. Maximally effective concentrations of fMLP (10−4 mol/L), C5a (7% zymosan activated serum), and rhIL-8 (250 ng/mL) were used. Net neutrophil movement per high power field (HPF) is defined as total neutrophils minus neutrophils migrating towards the media control (between 11 and 15 for different experiments). The data represent the mean from 4 individual mice per group each performed in triplicate. Bars represent standard deviations. (B) Quantitation of the total cells and neutrophils in peritoneal lavage fluid from thioglycolate-treated mice. Mice were injected with 2 mL of thioglycolate IP, and, at the indicated times, peritoneal cells were harvested by lavage and quantified. Cathepsin G +/+ and −/− mice demonstrate nearly identical numbers of total cells and neutrophils in the peritoneal harvests. This experiment was repeated 3 times with similar results. (C) Inflammation induced by IP injection of S aureus is not altered in cathepsin G−/− mice. S aureus (108CFU) was injected into the peritoneal cavities of 3 cathepsin G+/+ or −/− mice, and peritoneal lavage was performed 2 hours later. There is no significant difference between the total cells or the number of neutrophils harvested from cathepsin G+/+ or −/− mice. This experiment was repeated twice with similar results.

To determine whether in vivo chemotaxis was altered in cathepsin G−/− mice, we injected 2 mL (58 mg) of thioglycolate IP into cathepsin G+/+ and cathepsin G−/− mice and, at various time points, peritoneal cells were collected by lavage and quantified and cell type differentials were performed. As shown in Fig 5B, there was no difference in either the total number of cathepsin G+/+ and cathepsin G−/− cells or the number of cathepsin G+/+ and cathepsin G−/− neutrophils at 4 or 24 hours after injection. Similar results were obtained 48 hours after injection (data not shown).

To further assess in vivo chemotaxis, we wanted to determine whether cathepsin G−/− neutrophils would migrate normally to a site of bacterial infection. We therefore injected 3 cathepsin G+/+ and 3 cathepsin G−/− mice with 108 CFU of S aureus IP. At 2 hours, cells were harvested from the peritoneum and total cell counts and total number of neutrophils were determined, as shown in Fig 5C; there was no significant difference between the total number of cells or the total number of neutrophils in the peritoneal harvests from the wild-type versus cathepsin G−/− mice.

Finally, we wished to determine whether cathepsin G-deficient neutrophils had any defects in the early signaling pathways of fMLP, C5A, or IL-8. We therefore loaded wild-type or cathepsin G-deficient neutrophils with the calcium-sensitive dye Fluo-3 and added either no agonist (Mock) or optimal concentrations of fMLP (10−4 mol/L), C5a (7% Zymosan activated serum), or recombinant human IL-8 (250 ng/mL) and measured the mean fluorescent intensity in the neutrophils at 5-second intervals in Gr-1–positive cells. For each of the agonists, cathepsin G−/− neutrophils mediated calcium fluxes at least as efficiently as their wild-type counterparts (data not shown). This indicates that cathepsin G deficiency does not alter the function of the receptors for any of these chemoattractant molecules or reduce their ability to mediate calcium fluxes.

Normal survival of cathepsin G−/− mice in response toS aureus, K pneumoniae, or E coli challenges.

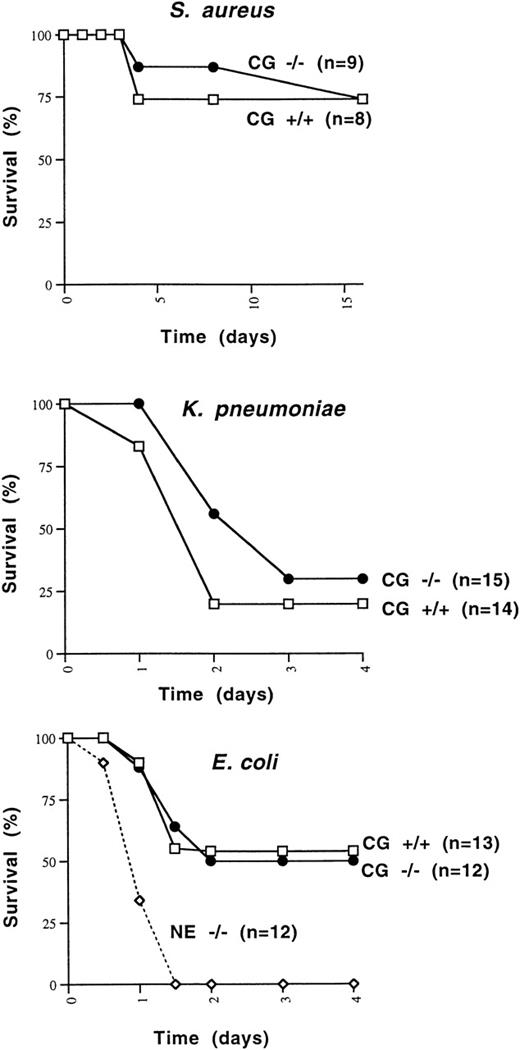

Because cathepsin G had previously been shown to be bactericidal for a variety of organisms, we wished to determine whether cathepsin G−/− mice were more susceptible to death induced by Gram-positive or Gram-negative bacterial species. We first determined that 108 CFU of S aureus killed 1 of 6 wild-type 129/SvJ mice, whereas 5 × 108 CFU killed 6 of 6 mice. We injected 1 × 108 CFU of S aureus IP into 8 additional cathepsin G+/+ and 9 cathepsin G−/− 129/SvJ mice. The survival of cathepsin G+/+ versus cathepsin G−/− animals was not significantly different (Fig 6A).

Survival of mice challenged with IP injections of S aureus, E coli, and K pneumoniae. (A) Cathepsin G+/+ or −/− mice in the 129/SvJ strain were challenged with 108 CFU of S aureus. There is no significant difference between the survival of +/+ and −/− animals. (B)K pneumoniae (1 × 106 CFU) was injected IP into cathepsin G+/+ or −/− animals in the 129/SvJ strain, and survival was plotted. No difference in survival was noted for the 2 groups. (C) Survival of wild-type, cathepsin G−/−, and NE−/− mice in response to IP challenge with E coli. E coli (3 × 104 CFU) was injected IP into groups of 12 cathepsin G−/−, NE−/−, and wild-type (+/+) littermates and survival was assessed over time. The survival of cathepsin G−/− mice is not different from that of wild-type, but the survival NE−/− mice is significantly less than that of the other groups (P ≤ .01).

Survival of mice challenged with IP injections of S aureus, E coli, and K pneumoniae. (A) Cathepsin G+/+ or −/− mice in the 129/SvJ strain were challenged with 108 CFU of S aureus. There is no significant difference between the survival of +/+ and −/− animals. (B)K pneumoniae (1 × 106 CFU) was injected IP into cathepsin G+/+ or −/− animals in the 129/SvJ strain, and survival was plotted. No difference in survival was noted for the 2 groups. (C) Survival of wild-type, cathepsin G−/−, and NE−/− mice in response to IP challenge with E coli. E coli (3 × 104 CFU) was injected IP into groups of 12 cathepsin G−/−, NE−/−, and wild-type (+/+) littermates and survival was assessed over time. The survival of cathepsin G−/− mice is not different from that of wild-type, but the survival NE−/− mice is significantly less than that of the other groups (P ≤ .01).

Similarly, we wanted to determine whether cathepsin G was required for the clearance of Gram-negative organisms. K pneumoniae andE coli were chosen, because neutrophil elastase-deficient mice have been shown to have a defect in the clearance of both organisms.80 Three different doses of K pneumoniae(1 × 105, 5 × 105, or 1 × 106 CFU) were injected IP into a total of 27 cathepsin G+/+ mice and 23 cathepsin G−/− mice. At every dose tested, the survival of cathepsin G−/− mice was not different from that of wild-type mice. Data from the 1 × 106 CFU dose are shown in Fig 6B. There is a trend toward fewer deaths in cathepsin G−/− mice, but this difference is not statistically significant.

Finally, we defined the LD50 for E coli in 129/SvJ mice, which was 3 × 104 CFU. This dose of bacteria was administered IP to 13 wild-type mice, 12 neutrophil elastase−/− mice, or 12 cathepsin G−/− mice, all in the pure 129/SvJ background. As shown in Fig 6C, the neutrophil elastase-deficient mice all succumb to the E coli infection within 48 hours, whereas approximately 50% of both wild-type and cathepsin G-deficient mice survive. The difference between the survival of NE−/− mice versus wild-type or cathepsin G−/− mice is statistically significant (P < .01).

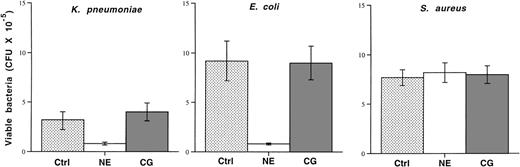

Human cathepsin G does not inhibit growth of E coli or K pneumoniae in vitro, but neutrophil elastase does.

Because previous reports of the microbicidal activities of cathepsin G had exclusively used purified human cathepsin G and because 2 of the microbicidal peptides of human cathepsin G (aa 77-83 and aa 117-136) are not completely conserved in mice (see Discussion), we decided to directly test and compare the microbicidal activities of highly purified human cathepsin G and neutrophil elastase. We incubated 105 mid-log phase bacteria in the absence or presence of purified human cathepsin G or neutrophil elastase (both at 50 μg/mL) for 4 hours. Bacterial killing was quantified by applying serial dilutions of bacteria to agarose plates followed by overnight incubation. Although human neutrophil elastase inhibits the growth of both K pneumoniae and E coli, as previously shown,80 the same dose of cathepsin G has no effect on the growth of either organism (Fig 7). Neither enzyme affects the growth of S aureus.

Purified human neutrophil elastase inhibits the growth ofE coli and K pneumoniae, but human cathepsin G does not. Mid-log phase bacteria (105) were incubated in the absence (control) or presence of purified human neutrophil elastase or cathepsin G at 37°C for 4 hours, as described in Materials and Methods. Serial dilutions were immediately spread on agarose plates and the number of CFUs was determined after overnight incubation. Although neutrophil elastase inhibits the growth of both Gram-negative rods, cathepsin G does not. Neither enzyme effects the growth of S aureus. This experiment was repeated twice with similar results.

Purified human neutrophil elastase inhibits the growth ofE coli and K pneumoniae, but human cathepsin G does not. Mid-log phase bacteria (105) were incubated in the absence (control) or presence of purified human neutrophil elastase or cathepsin G at 37°C for 4 hours, as described in Materials and Methods. Serial dilutions were immediately spread on agarose plates and the number of CFUs was determined after overnight incubation. Although neutrophil elastase inhibits the growth of both Gram-negative rods, cathepsin G does not. Neither enzyme effects the growth of S aureus. This experiment was repeated twice with similar results.

DISCUSSION

In this report, we describe mice bearing a loss-of-function mutation of the cathepsin G gene. These mice have normal growth, development, and fertility and display normal hematopoietic development. The neutrophils of cathepsin G−/− mice have normal morphology, normal phagocytosis, and normal production of superoxide in response to in vitro stimuli. These neutrophils have no defect in their ability to migrate towards a variety of chemotactic stimuli in vitro and in vivo. Cathepsin G−/− mice are able to clear S aureus,K pneumoniae, and E coli infections as efficiently as wild-type animals, suggesting that this enzyme is not necessary for the normal clearance of any of these bacterial species.

Even though cathepsin G is one of the most abundant proteins found in human and mouse neutrophils, mice that are deficient for this enzyme have no clear-cut phenotype, except for a transient defect in wound healing that is accompanied by excessive neutrophilic infiltration of wounds.65 The minimal phenotype observed is quite surprising, because a large body of literature has strongly suggested that cathepsin G might have specific, nonredundant functions in physiologic settings.

One potential reason for the lack of an obvious phenotype in these animals is that the cathepsin G mutation is not truly null. However, cathepsin G mRNA and protein are not detectable in cathepsin G−/− mice. Even more importantly, bone marrow extracts from cathepsin G−/− mice have no detectable ability to cleave the peptide substrate N-Succinyl-Ala-Ala-Pro-Phe-pNA. The complete lack of protease activity against this substrate indicates that there are no other enzymes with the same specificity in the bone marrow. This result also suggests that, if the functions of cathepsin G can be rescued by other proteases (eg, neutrophil elastase, azurocidin, and/or proteinase-3, which are all presumably present at normal levels in cathepsin G−/− mice), then these functions must be rescued by protease activities that are different from that of cathepsin G. This result argues that the gene that we have knocked-out is indeed the functional orthologue of human cathepsin G, because human cathepsin G also cleaves this peptide substrate with high specificity. It is also possible that cathepsin G has specific functions that are masked by the presence of the other related azurophil granule proteases in vivo. Neutrophil elastase, azurocidin, and proteinase-3 are clustered on a different chromosome (19 pter) and are coordinately regulated and expressed along with cathepsin G in the azurophil granules of promyelocytes. The functions of these highly related proteases may be difficult to fully define until mice deficient for more than 1 of these enzymes are analyzed.

The only assay that suggests that cathepsin G may have unique substrates in vivo is wound healing. In the wound healing studies, we learned that incisional wounds displayed a significant reduction in tensile strength on day 7 after wounding; this defect was associated with increased neutrophilic inflammation at the site of wounding.65 The wound strength had completely normalized by day 10. The wound fluid of cathepsin G-deficient mice contained significantly increased chemotactic activity for wild-type neutrophils, suggesting that increased levels of proinflammatory cytokines (or other mediators) were present in this wound fluid. Indirectly, these data suggest that cathepsin G may be involved in inactivating proinflammatory molecules at the sites of wound injury, thereby providing a dampening effect on continued neutrophil influx at these sites. Although the precise molecules responsible for this effect are not known, the ability of cathepsin G to cleave and inactivate IL-1, TNF, and IL-854-56 suggest that one or more of these molecules could be involved in this process.

Cathepsin G has been shown to cleave and inactivate several clotting factors,21-26 cleave and/or modulate the function of the thrombin receptor,27-29 and activate platelets in vitro.30-38 However, we found no gross hemostatic defects in cathepsin G−/− animals. Because neutrophil elastase has activity in many of the same in vitro assays involving clotting factors and platelet activation, this enzyme may be capable of substituting for cathepsin G in this setting; however, neutrophil elastase deficient mice also have no obvious defects in hemostasis.80 It will therefore be important to determine whether mice doubly deficient for both cathepsin G and neutrophil elastase have more severe defects in hemostasis.

Cathepsin G-deficient mice have no apparent defect in their ability to clear S aureus, K pneumoniae, or E coli. A large number of studies had previously suggested that purified human cathepsin G had growth-inhibitory effects and/or bactericidal effects on S aureus, E coli, and additional bacteria in vitro and that the protease activity of cathepsin G was not required for this effect. Three different peptides derived from human cathepsin G (aa 1-5, aa 77-83, and aa 117-136) have been shown to have microbicidal activity. Although the first peptide (aa 1-5) is conserved in the mouse, the sequence of the second peptide (aa 77-83) in mice is HPDYNPQ. Alanine substitutions in positions 3, 6, and 7 of the human HPQYNQR peptide each reduce bactericidal activity of the peptide by approximately 2.5-fold.48 The third peptide (aa 117-136) contains 16 of 20 identical residues in the mouse, but 2 of the 4 arginine residues that are important for microbicidal function are altered (Arg 117 Gln and Arg 133 Ser). Because the 77-83 and 117-136 peptides are not completely conserved, it is possible that human cathepsin G is important for bacterial killing, but murine cathepsin G is not. However, in this study, we have not been able to demonstrate a role for human cathepsin G in bacterial killing in vitro, in contrast to previously published work. Although we do not understand the reason for this difference, our in vitro and in vivo results do corroborate one another.

Neutrophil elastase-deficient mice have a defect in their ability to clear both K pneumoniae and E coli.80Purified human neutrophil elastase inhibits the growth of these two Gram-negative rods, but equivalent concentrations of human cathepsin G had no inhibitory activity. The preparations of enzymes that were used in these assay were both fully active, and the concentrations of the enzymes were carefully confirmed. Therefore, human and murine neutrophil elastase both have a specific, nonredundant ability to kill Gram-negative rods in vitro and in vivo; cathepsin G cannot substitute for this function in either setting.

Several recent studies have suggested that cathepsin G is not only found in the azurophil granules of neutrophils, but also on the surface of these cells.17,18,81 A role for cathepsin G on the cell surface has been suggested by the fact that α1 antichymotrypsin (and also antibodies specific for cathepsin G) can reduce the ability of neutrophils to undergo chemotaxis towards a variety of stimuli.19,20 These results suggested that cell surface-associated cathepsin G may play a specific role in the chemotactic response. Additionally, cathepsin G itself has been shown to have chemotactic activity for neutrophils and monocytes, suggesting that cathepsin G release by neutrophils may amplify a chemoattractant response.82 However, our data showed that there is no specific chemotactic defect for cathepsin G-deficient neutrophils using fMLP, C5a, or rhIL-8 as the chemotactic stimuli. Similarly, neutrophil calcium fluxes induced by these 3 molecules are essentially normal in cathepsin G−/− neutrophils. In vivo, we observed no clear defect in the ability of neutrophils to migrate into the peritoneal space of mice treated with thioglycolate or S aureus, suggesting that the in vivo chemoattractant response (and also the ability of neutrophils to leave the circulation and migrate into the peritoneal space) is not impaired in these mice. Although the possibility clearly exists that other proteases can substitute for the function of cathepsin G in this setting, it is also possible that cathepsin G may not be required for neutrophil chemotaxis in vivo.

Lymphokine-activated killer cells derived from mice that contain a retained PGK-neo cassette in the granzyme B gene demonstrate a loss of granzyme B mRNA, as expected, but also lose expression of granzymes C, D, F, and G. This phenomenon, known as the neighborhood effect, is thought to be due to the productive interaction of a locus control region (LCR; presumably upstream from granzyme B) with the PGK-neo cassette; this may disrupt normal interactions between the LCR and the downstream granzyme genes. In mice containing the granzyme B mutation, cathepsin G mRNA levels are normal.10,66 We have also shown that the retained PGK-neo cassette in the cathepsin G gene has minimal effects on the expression of the granzymes, suggesting that the neighborhood effect is predominantly unidirectional.10 In this report, we show that mast cells cultured in vitro from cathepsin G-deficient mice contain no cathepsin G mRNA, as expected, but also demonstrate a 10-fold reduction in mMCP-2 mRNA levels. These data strongly suggest that the retained PGK-neo cassette in the cathepsin G gene has a neighborhood effect on the mMCP-2 gene (and perhaps on additional members of the mast cell chymase family located further downstream). These data also suggest that this large protease gene cluster may contain at least 2 distinct regulatory domains. One domain would include all of the granzyme genes upstream from cathepsin G; this domain may be regulated by an LCR near granzyme B. The second domain, which would include cathepsin G and the mast cell chymases, may be controlled by a separate LCR that is active in the myeloid compartment, but not the NK/T-compartment. Further experiments will be required to test this hypothesis.

In summary, our experiments have shown that many of the previously defined in vitro activities of cathepsin G are either irrelevant or redundant when a whole animal model of cathepsin G deficiency is examined. Additional experiments will be required to further define the normal functions of cathepsin G, using mice that are also deficient for neutrophil elastase or the related azurophil granule proteases azurocidin and/or proteinase 3.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Dr Bob Senior for many helpful discussions, Robin Wesselschmidt for blastocyst injections, and Pam Goda and Kelly Schrimpf for excellent animal care. We thank Dan Link and Jeff Haug for performing the neutrophil calcium flux assays, Diane Kelley for the chemotaxis assays, Marilyn Levy for Transmission Electron Microscopy, and Sujan Shresta for the flow studies of lymphoid organs. Nancy Reidelberger expertly prepared the manuscript.

Supported by National Institutes of Health Grants No. DK49786 and CA49712 (to T.J.L.), BL03774 (to C.T.N.P.), and HL54853 (to S.D.S.).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to Timothy J. Ley, MD, Washington University Medical School, Division of Bone Marrow Transplantation and Stem Cell Biology, 660 S Euclid Ave, Campus Box 8007, St Louis, MO 63110; e-mail:timley@im.wustl.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal