Sickle red blood cells (SS-RBCs) have enhanced adhesion to the plasma and subendothelial matrix protein thrombospondin-1 (TSP) under conditions of flow in vitro. TSP has at least four domains that mediate cell adhesion. The goal of this study was to map the site(s) on TSP that binds SS-RBCs. Purified TSP proteolytic fragments containing either the N-terminal heparin-binding domain, or the type 1, 2, or 3 repeats, failed to sustain SS-RBC adhesion (<10% adhesion). However, a 140-kD thermolysin TSP fragment, containing the carboxy-terminal cell-binding domain in addition to the type 1, 2, and 3 repeats fully supported the adhesion of SS-RBCs (126% ± 25% adhesion). Two cell-binding domain adhesive peptides, 4N1K (KRFYVVMWKK) and 7N3 (FIRVVMYEGKK), failed to either inhibit or support SS-RBC adhesion to TSP. In addition, monoclonal antibody C6.7, which blocks platelet and melanoma cell adhesion to the cell-binding domain, did not inhibit SS-RBC adhesion to TSP. These data suggest that a novel adhesive site within the cell binding domain of TSP promotes the adhesion of sickle RBCs to TSP. Furthermore, soluble TSP did not bind SS-RBCs as detected by flow cytometry, nor inhibit SS-RBC adhesion to immobilized TSP under conditions of flow, indicating that the adhesive site on TSP that recognizes SS-RBCs is exposed only after TSP binds to a matrix. We conclude that the intact carboxy-terminal cell-binding domain of TSP is essential for the adhesion of sickle RBCs under flow conditions. This study also provides evidence for a unique adhesive site within the cell-binding domain that is exposed after TSP binds to a matrix.

SICKLE CELL DISEASE is caused by a genetic disorder of hemoglobin (hemoglobin β Glu6Val) that results in hemolytic anemia.1-3 The major cause of morbidity and mortality in sickle cell disease is tissue ischemia and infarction due to vascular occlusion. The pathogenesis of vaso-occlusion remains incompletely understood and likely involves many heterogeneous steps. The sickle erythrocyte manifests numerous abnormalities that include oxidative damage of membrane proteins and lipids,4 aberrant cation homeostasis resulting in significant cellular dehydration,5 abnormal clustering of surface proteins,6 disruption of the membrane phospholipid asymmetry,7 and increased adhesive properties.2,3 The increased adhesion of sickle red blood cells (SS-RBCs) to vascular endothelium in vitro has been described using both static adhesion assays8 and endothelialized flow chambers.9 These observations have been confirmed using live animal models by either infusing human SS-RBCs into rats10,11or by studying transgenic sickle cell mouse models.12 The enhanced adhesion of SS-RBCs to the vascular endothelium and subendothelial matrix likely plays a significant role in the pathogenesis of vascular occlusion in sickle cell disease.

Thrombospondin-1 (TSP) is a 450-kD, homotrimeric glycoprotein present in the subendothelial matrix, plasma, and platelet α storage granules that can be released in high local concentrations by activated platelets.13,14 TSP mediates cell attachment and spreading, stabilizes platelet aggregation, regulates cell growth, and plays a role in angiogenesis, wound healing, cell migration, and phenotypic differentiation. TSP has at least four domains that mediate cell adhesion, including the NH2-terminal heparin-binding domain that also binds sulfated glycolipids and heparan sulfate proteoglycans,15,16 sequences within the type 1 repeats that associate with CD36,17 the RGD integrin-binding site within the last type 3 repeat of the calcium binding domain,18 and the carboxy-terminal cell binding domain that binds to platelets and transformed cells.19 Chondroitin sulfate A also binds to TSP, likely through regions within the type 1 repeats or the carboxy-terminal cell binding domain.20Similar to other adhesion molecules,21 the binding characteristics of TSP can be affected by conformational changes.22

Soluble TSP has been shown to enhance the adhesion of SS-RBCs to cultured endothelial cells.23,24 SS-RBCs also bind avidly to purified, immobilized TSP under conditions of flow in vitro.25,26 The adhesion of sickle RBCs to TSP may contribute to vaso-occlusive crises in sickle cell disease. Although the sickle reticulocyte adhesive receptor CD36 is postulated to mediate the adhesion of SS-RBCs to endothelial cells,23,24 the adhesion of SS-RBCs to immobilized TSP is probably not mediated by CD36.25 26 The specific molecular mechanisms by which TSP binds sickle RBCs is not known. Therefore, in this study we sought to determine the site on TSP that binds the sickle RBC under conditions of flow in vitro. We found that the 20-kD carboxy-terminus of TSP that contains the cell-binding domain was required for SS-RBC adhesion. Additionally, we determined that site on TSP that binds SS-RBCs is exposed after binding to a matrix and likely involves a unique adhesive region(s) within the cell-binding domain.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

RBC and G361 cell preparation and flow adhesion assay.

After obtaining informed consent, blood samples were collected from patients with hemoglobin SS disease in 3.8% sodium citrate (1:9). The RBCs were washed three times and resuspended at a 2% hematocrit in M199 serum-free cell culture medium (Sigma, St Louis, MO) containing 0.2% bovine serum albumin (BSA, buffer A) as previously described.25 G361 melanoma cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Rockville, MD) (CRL 1424) and cultured in McCoy’s 5A medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum at 5% CO2. Cells were detached using trypsin-EDTA, washed twice with medium, and resuspended at 1 × 106/mL in buffer A. SS-RBC or G361 cell adhesion was studied using a parallel plate perfusion chamber as previously described.25,27 In brief, intact or purified TSP fragments were coated on 35-mm2 tissue culture plates (2 μg/cm2, 60 minutes, room temperature) which served as the adhesive surface of the flow chamber. An initial rinse period of 3 to 5 minutes with buffer A containing BSA served to block the treated plates.25 Washed cells suspended in buffer A (2.5 to 3 mL) were perfused through the flow chamber at a wall shear stress of 1 dyne/cm2, a force similar to that found in the postcapillary venule. After a 5- to 10-minute rinse period, the number of adherent cells per unit surface area were counted by direct microscopic visualization of the adhesive surface in a previously calibrated grid of known area in 4 to 6 random areas near the center of the flow surface. For inhibition experiments, the reagent being tested was incubated with either the cell suspension or the adhesive surface for 30 minutes at 37°C before the initiation of the flow adhesion assay. All flow adhesion experiments were performed at 37°C using an air curtain incubator.

Purification and proteolytic digestion of TSP.

TSP was purified from washed, activated (thrombin receptor activation peptide SFLL, 5 μmol/L and thromboxane A2 analogue U46619, 0.5 μmol/L) platelet releasate by gel filtration on Sepharose 4B (Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ) followed by affinity chromatography on heparin-Sepharose as previously described.14 The 25-kD NH2-terminal heparin-binding domain and the 140-kD carboxy-terminal proteolytic TSP fragments were prepared by thermolysin digestion (1:100, wt:wt) in the presence of 1 mmol/L CaCl2in Tris-buffered saline (TBS, 20 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 150 mmol/L NaCl) for 60 minutes at room temperature. The digestion was terminated by the addition of threefold excess (wt/wt) phosphoramidone and the fragments purified by heparin-Sepharose FPLC affinity chromatography (Pharmacia) as previously described.16 The 70-kD proteolytic TSP fragment was generated by chymotrypsin digestion (1:100, wt:wt) in the presence of 10 mmol/L EDTA in TBS, pH 7.4, for 30 minutes at room temperature followed by purification using gel filtration chromatography (Superdex HR 75 FPLC; Pharmacia) as previously described.28 29 To generate the 120-kD proteolytic TSP fragment that contains the type 1, 2, and 3 repeats (Ca2+ binding domain), TSP was treated with chymotrypsin (1:100, wt:wt) in the presence of 1 mmol/L CaCl2 in TBS for 5 to 60 minutes at room temperature. All chymotrypsin digestions were terminated by the addition of threefold excess (wt/wt) phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF). The TSP digests and purified TSP fragments were resolved by 4% to 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) with or without reduction using 2-mercaptoethanol followed by Coomassie blue staining. Because the intact 20-kD TSP cell-binding domain remains disulfide linked, we were not able to obtain this proteolytic fragment.

TSP peptides and monoclonal antibodies (MoAbs).

Mouse IgG1 MoAb C6.7, which recognizes the cell-binding domain of TSP and functionally blocks the binding of platelets and melanoma cell to TSP,30,31 was provided by William A. Frazier (Washington University, St Louis, MO). Mouse IgM MoAb A4.1 is directed against the type 1 repeats of TSP29 and was purchased from GIBCO-BRL (Gaithersburg, MD). The control IgG1 MoAb MBC 35.5 is directed against protein C. The control IgM MoAb MBC 45.7 is directed against protein S. The TSP cell-binding domain adhesive peptides KRFYVVMWKK (4N1K) and FIRVVMYEGKK (7N3), scrambled control peptide VKMKWKYVRF, and peptides GRGDW and GRGEW were synthesized on a MilliGen 9050 PepSynthesizer (Millipore) and purified by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). For studies requiring immobilized peptide, the 4N1K, 7N3, and scramble control resin bound peptides were conjugated to BSA by incubating with 1,3 diisopropylcarbodiimide and hydroxybenzotriazole in dimethylacetamide overnight at room temperature. The BSA-coupled peptides were cleaved from the resin and side chains groups removed followed by precipitation in ether and desalting.

Flow cytometry experiments.

Washed SS-RBCs were resuspended to 10% hematocrit in TBS containing 1 mmol/L Ca2+ and 0.2% BSA (TBS-BSA/Ca2+) and incubated with purified TSP (1 to 1.4 mg/mL) for 60 minutes at 37°C. After two washes in TBS-BSA/Ca+2, treated SS-RBCs were incubated with mouse MoAb A4.1, isotype-specific negative control MoAb MBC 45.7 (IgM, ascites, diluted 1:100 to 1:10,000), or positive control MoAb E5 that recognizes glycophorin C (Sigma; IgG1, ascites, diluted 1:600) for 60 minutes at room temperature. After two washes, RBCs were incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-mouse IgG or IgM (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) for 30 minutes at room temperature and bound antibody detected by flow cytometry.

RESULTS

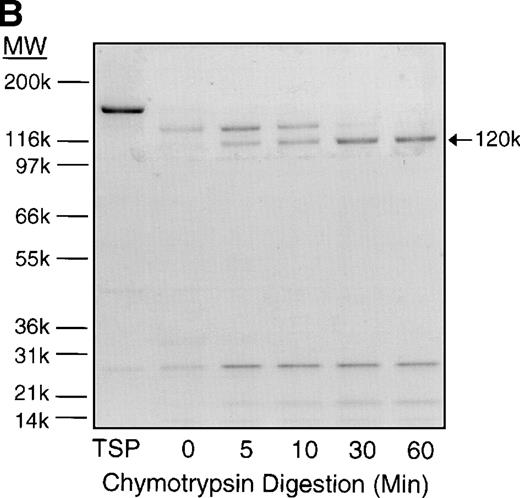

To define the region of TSP that binds to sickle RBCs, several strategies were used to generate and purify proteolytic fragments of TSP. Thermolysin digestion of purified TSP in the presence of Ca2+ yielded a 25-kD fragment that contains the NH2-terminal heparin-binding domain, and a 140-kD carboxy-terminal proteolytic fragment (Fig 1).16Chymotrypsin digestion of TSP in the presence of EDTA yielded a 70-kD TSP fragment that contained the type 1 and type 2 repeats. Alternatively, chymotrypsin digestion of TSP in the presence of Ca2+, to protect the Ca2+-binding domain from proteolytic cleavage, resulted in a 120-kDa carboxy-terminal proteolytic fragment that is similar to the 140-kD fragment except for cleavage of the terminal 18 to 20 kD of the carboxy-terminus that contains the cell-binding domain.28 Similar to previous reports,16,29,32 resolution of the TSP fragments by SDS-PAGE under nonreducing conditions showed that the 25-kD fragment was a monomer, while the 70-kD, 120-kD, and 140-kD fragments remained trimers (data not shown). Additionally, the 18- to 20-kD C-terminal fragment that is cleaved from the 140-kD fragment to form the 120-kD fragment remains linked by disulfide bonds.31

SS-RBCs bind to the 140-kD carboxy-terminal proteolytic fragment of TSP. (A) Schematic illustration of intact TSP with selected domains as described in the text (HBD, heparin-binding domain; type 1, type 1 repeats; type 2, type 2 repeats; Ca++ Binding, Ca2+-binding domains or type 3 repeats; CBD, cell-binding domain). The approximate locations of the 25-kD, 140-kD, 120-kD, and 70-kD proteolytic fragments as identified by amino-terminal sequencing and size16,29,32are indicated by arrows. The 25-kD fragment is a monomer,16the 70-kD, 120-kD, and 140-kD fragments are trimers,32 and the 18- to 20-kD C-terminal fragment remains disulfide linked to the 120-kD fragment.31 (B) Proteolytic digestion and purification of TSP fragments. TSP purified from platelet releasate was treated with thermolysin and purified by heparin-Sepharose affinity chromatography, or chymotrypsin in the presence of Ca2+or EDTA and purified by gel-filtration FPLC as described in Materials and Methods. Intact TSP (TSP), proteolyzed TSP (Thermolysin, Chtpn), or purified proteolytic fragments (140 kDa, 25 kDa, 70 kDa, 120 kDa) were resolved by 4% to 12% SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie Blue. (C) Washed SS-RBCs were perfused through parallel plate flow chambers coated (2 μg/cm2) with intact TSP (TSP, N = 12) or purified 25-kD (25 kDa, N = 4), 140-kD (140 kDa, N = 4), 70-kD (70 kDa, N = 4), or 120-kD (120 kDa, N = 4) TSP fragments at a wall shear stress of 1 dyne/cm2. After rinsing, adherent RBCs per unit area were counted by direct microscopic visualization. The results are shown as the mean ± SE of SS-RBC adhesion, normalized to SS-RBC adhesion to intact TSP.

SS-RBCs bind to the 140-kD carboxy-terminal proteolytic fragment of TSP. (A) Schematic illustration of intact TSP with selected domains as described in the text (HBD, heparin-binding domain; type 1, type 1 repeats; type 2, type 2 repeats; Ca++ Binding, Ca2+-binding domains or type 3 repeats; CBD, cell-binding domain). The approximate locations of the 25-kD, 140-kD, 120-kD, and 70-kD proteolytic fragments as identified by amino-terminal sequencing and size16,29,32are indicated by arrows. The 25-kD fragment is a monomer,16the 70-kD, 120-kD, and 140-kD fragments are trimers,32 and the 18- to 20-kD C-terminal fragment remains disulfide linked to the 120-kD fragment.31 (B) Proteolytic digestion and purification of TSP fragments. TSP purified from platelet releasate was treated with thermolysin and purified by heparin-Sepharose affinity chromatography, or chymotrypsin in the presence of Ca2+or EDTA and purified by gel-filtration FPLC as described in Materials and Methods. Intact TSP (TSP), proteolyzed TSP (Thermolysin, Chtpn), or purified proteolytic fragments (140 kDa, 25 kDa, 70 kDa, 120 kDa) were resolved by 4% to 12% SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie Blue. (C) Washed SS-RBCs were perfused through parallel plate flow chambers coated (2 μg/cm2) with intact TSP (TSP, N = 12) or purified 25-kD (25 kDa, N = 4), 140-kD (140 kDa, N = 4), 70-kD (70 kDa, N = 4), or 120-kD (120 kDa, N = 4) TSP fragments at a wall shear stress of 1 dyne/cm2. After rinsing, adherent RBCs per unit area were counted by direct microscopic visualization. The results are shown as the mean ± SE of SS-RBC adhesion, normalized to SS-RBC adhesion to intact TSP.

When the purified 25-kD N-terminal heparin-binding domain of TSP was immobilized on the surface of the flow adhesion chamber, it supported only 9% of the binding activity of SS-RBCs to intact TSP under flow conditions (Fig 1C). The 70-kD and 120-kD chymotryptic TSP fragments that contain the procollagen-like segment, and type 1, 2, and 3 repeats also did not support SS-RBC adhesion. However, the 140-kD TSP fragment, containing the carboxy-terminal cell-binding domain in addition to the type 1, 2, and 3 repeats of TSP, fully supported the adhesion of SS-RBCs. As shown by the sequential chymotrypsin digestion of TSP in Fig 2, the binding activity of TSP dissipated coincident with the progressive cleavage of TSP fragments larger than 120 kD containing the carboxy-terminal cell binding domain. These data indicate that the 20-kD carboxy-terminal segment of TSP, which contains the cell-binding domain, is required for SS-RBC adhesion to immobilized TSP under flow conditions.

Time course of TSP chymotrypsin digestion and its effect on SS-RBC adhesion. (A) TSP was incubated in the presence of CaCl2 (1 mmol/L) with control buffer containing PMSF-inactivated chymotrypsin (time = 0 minutes) or active chymotrypsin (1:100, wt:wt) for 5, 10, 30, or 60 minutes before stopping the reaction with PMSF. Treated TSP was coated (2 μg/cm2) on flow-chamber wells followed by perfusion of washed SS-RBCs as described in the legend to Fig 1. The results are shown as the mean ± SE of SS-RBC adhesion, normalized to SS-RBC adhesion to control-buffer–treated TSP (N = 3 to 9 for each time point). (B) TSP treated with control buffer (PMSF-inactivated chymotrypsin, 0) or chymotrypsin (5, 10, 30 or 60 minutes) was resolved by 4% to 20% SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie Blue. Note that the heparin-binding domain (25 kD) is cleaved during the incubation with the control buffer, leaving the fully active 140-kD TSP fragment.

Time course of TSP chymotrypsin digestion and its effect on SS-RBC adhesion. (A) TSP was incubated in the presence of CaCl2 (1 mmol/L) with control buffer containing PMSF-inactivated chymotrypsin (time = 0 minutes) or active chymotrypsin (1:100, wt:wt) for 5, 10, 30, or 60 minutes before stopping the reaction with PMSF. Treated TSP was coated (2 μg/cm2) on flow-chamber wells followed by perfusion of washed SS-RBCs as described in the legend to Fig 1. The results are shown as the mean ± SE of SS-RBC adhesion, normalized to SS-RBC adhesion to control-buffer–treated TSP (N = 3 to 9 for each time point). (B) TSP treated with control buffer (PMSF-inactivated chymotrypsin, 0) or chymotrypsin (5, 10, 30 or 60 minutes) was resolved by 4% to 20% SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie Blue. Note that the heparin-binding domain (25 kD) is cleaved during the incubation with the control buffer, leaving the fully active 140-kD TSP fragment.

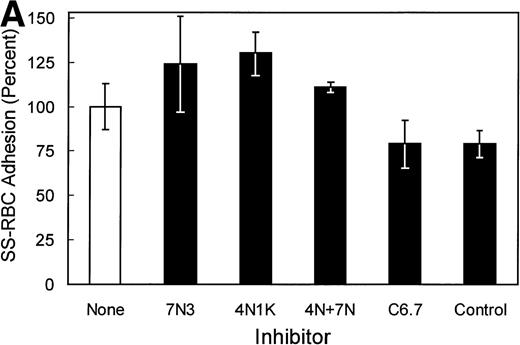

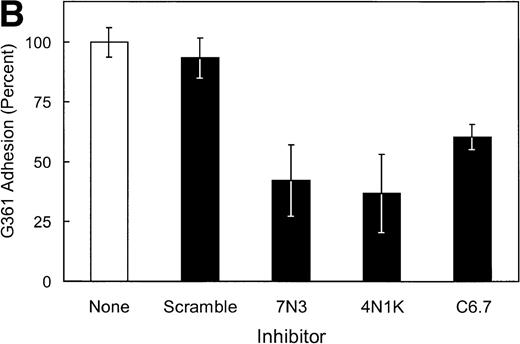

In studies to further map potential adhesive sites within the cell-binding domain of TSP that bind SS-RBCs, the anti-TSP MoAb C6.7, which blocks the binding of platelets and transformed cells to the TSP cell-binding domain,30 was tested for its effect on SS-RBC adhesion. As shown in Fig 3A, anti-TSP MoAb C6.7 did not significantly inhibit SS-RBC adhesion to TSP compared with isotype-specific control MoAb. The peptides 4N1K (KRFYVVMWKK) and 7N3 (FIRVVMYEGKK) are two well-characterized cell-binding domain adhesive sequences that both inhibit as well as support TSP-mediated adhesion of platelets and transformed cells.19 When the peptides 4N1K or 7N3 were incubated with the SS-RBCs during the flow adhesion assay, both peptides, either alone or in combination, failed to inhibit SS-RBC adhesion to intact TSP (Fig 3A). In contrast, G361 melanoma cells, which are reported to attach to TSP via the cell-binding domain,19,33 bound to immobilized TSP under the same conditions of low shear flow as the SS-RBC adhesion (Fig 3B). Similar to previous reports under static conditions,19 33 the adhesion of G361 cells to TSP was significantly inhibited by peptides 7N3 and 4N1K as well as MoAb C6.7 under flow conditions (Fig 3B,P < .05). Additionally, when the albumin-conjugated peptides 4N1K and/or 7N3 were immobilized to the surface of the flow adhesion assay (2 μg/cm2), neither peptide supported SS-RBC adhesion (<5% adhesion, N = 3 to 9, data not shown). These data suggest that these known adhesive epitopes within the TSP cell-binding domain are not involved in the adhesion of sickle RBCs to immobilized TSP under flow conditions.

Effect of TSP cell-binding domain inhibitory antibodies and peptides on SS-RBC adhesion to TSP. (A) Washed SS-RBCs were incubated with control buffer (None), 7N3 peptide FIRVVMYEGKK (7N3, 200 μmol/L, N = 2), 4N1K peptide KRFYVVMWKK (4N1K, 200 μmol/L, N = 2), or both 4N1K and 7N3 peptides (4N+7N, 200 μmol/L, N = 2) for 60 minutes at 37°C before the flow adhesion assay. Treated RBCs were perfused through flow chambers coated with immobilized TSP as described in the legend to Fig 1. Immobilized TSP was incubated with 5 μg/mL purified anti-TSP MoAb 6.7 (C6.7) or isotype-specific control MoAb MBC 35.5 (Control) for 30 minutes at 37°C before performing the flow adhesion assay as described above (N = 3). Similar results were found incubating SS-RBCs with MoAbs in ascites fluid (C6.7 and MBC 35.5, diluted 1:1,000) before the flow adhesion assay (N = 9). (B) G361 cells were incubated with control buffer (None, N = 4), scramble control peptide (Scramble, 200 μmol/L, N = 8) 7N3 peptide (7N3, 200 μmol/L, N = 4), 4N1K peptide (4N1K, 200 μmol/L, N = 4), or immobilized TSP was incubated with anti-TSP MoAb 6.7 (C6.7, N = 4) for 30 to 90 minutes at 37°C before the flow adhesion assay. G361 cells were then perfused through the flow chambers coated with immobilized TSP as described in Fig 1.

Effect of TSP cell-binding domain inhibitory antibodies and peptides on SS-RBC adhesion to TSP. (A) Washed SS-RBCs were incubated with control buffer (None), 7N3 peptide FIRVVMYEGKK (7N3, 200 μmol/L, N = 2), 4N1K peptide KRFYVVMWKK (4N1K, 200 μmol/L, N = 2), or both 4N1K and 7N3 peptides (4N+7N, 200 μmol/L, N = 2) for 60 minutes at 37°C before the flow adhesion assay. Treated RBCs were perfused through flow chambers coated with immobilized TSP as described in the legend to Fig 1. Immobilized TSP was incubated with 5 μg/mL purified anti-TSP MoAb 6.7 (C6.7) or isotype-specific control MoAb MBC 35.5 (Control) for 30 minutes at 37°C before performing the flow adhesion assay as described above (N = 3). Similar results were found incubating SS-RBCs with MoAbs in ascites fluid (C6.7 and MBC 35.5, diluted 1:1,000) before the flow adhesion assay (N = 9). (B) G361 cells were incubated with control buffer (None, N = 4), scramble control peptide (Scramble, 200 μmol/L, N = 8) 7N3 peptide (7N3, 200 μmol/L, N = 4), 4N1K peptide (4N1K, 200 μmol/L, N = 4), or immobilized TSP was incubated with anti-TSP MoAb 6.7 (C6.7, N = 4) for 30 to 90 minutes at 37°C before the flow adhesion assay. G361 cells were then perfused through the flow chambers coated with immobilized TSP as described in Fig 1.

Because multiple adhesive epitopes may participate in the binding of sickle RBCs to TSP, other potential adhesive domains of TSP were studied. The last type 3 repeat within the TSP Ca2+-binding domain contains the adhesive tripeptide RGD motif that participates in the binding of TSP to integrin receptors.18 As shown in Fig 4, the peptide RGDW, which blocks the binding of cells to TSP via integrins, failed to significantly inhibit SS-RBC binding to TSP compared with control RGEW peptide. Although there was some decrease in SS-RBC adhesion in the presence of the RGDW, the levels were similar to the inactive RGE control peptide, suggesting a nonspecific peptide effect. Additionally, there was no dose-response effect, with similar results obtained using concentrations of RGD peptide ranging from 200 μmol/L to 1 mmol/L (data not shown). Therefore, it is unlikely that the adhesive RGD motif contributes to SS-RBC binding to immobilized TSP under low shear flow conditions. When immobilized TSP was incubated with EDTA, known to affect the conformation of both the Ca2+-binding domain as well as the cell-binding domain, SS-RBC adhesion was inhibited by 66% (Fig 4). When TSP was incubated with EDTA (5 mmol/L) followed by replacement of Ca2+, SS-RBC adhesion to TSP was fully restored, demonstrating that the EDTA effect on TSP was reversible (Fig 4).

The role of calcium and RGD in SS-RBC adhesion to TSP. Washed SS-RBCs were incubated with control buffer (None, N = 19), GRGDW (RGD, 200 μmol/L, N = 12), or control peptide GRGEW (RGE, 200 μmol/L, N = 12) for 30 minutes at 37°C before perfusing through flow chambers precoated with TSP. Immobilized TSP was incubated with EDTA (EDTA, 5 mmol/L, 30 minutes, N = 5) or EDTA (5 mmol/L, 30 minutes) followed by 10 mmol/L CaCl2(EDTA/Ca2+ N = 3) before performing the flow adhesion assay as described above.

The role of calcium and RGD in SS-RBC adhesion to TSP. Washed SS-RBCs were incubated with control buffer (None, N = 19), GRGDW (RGD, 200 μmol/L, N = 12), or control peptide GRGEW (RGE, 200 μmol/L, N = 12) for 30 minutes at 37°C before perfusing through flow chambers precoated with TSP. Immobilized TSP was incubated with EDTA (EDTA, 5 mmol/L, 30 minutes, N = 5) or EDTA (5 mmol/L, 30 minutes) followed by 10 mmol/L CaCl2(EDTA/Ca2+ N = 3) before performing the flow adhesion assay as described above.

To further study other potential adhesive regions on TSP, we developed a murine MoAb (TSP-N1) that binds to the N-terminal 25-kD heparin-binding domain of TSP as determined by immunoblot of intact and thermolysin digested TSP (data not shown). However, this MoAb did not significantly inhibit SS-RBC adhesion to immobilized TSP (104% ± 13% adhesion, N = 6). Furthermore, incubation of immobilized TSP with anti-TSP MoAb 4.1 that is directed against the type 1 repeats16 19 failed to inhibit SS-RBC adhesion to TSP (data not shown). These data are in agreement with the above proteolytic TSP fragment studies where neither the 25-kD N-terminal TSP fragment containing the heparin-binding domain nor the 70-kD fragment containing the type 1 repeats supported SS-RBC adhesion.

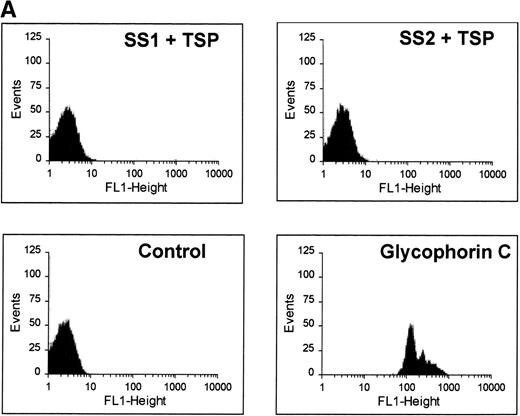

The binding characteristics of many of adhesive ligands can vary depending on the shear force (eg, von Willebrand factor)34and whether the ligand is in solution phase versus the solid phase (eg, fibrinogen).21 Although immobilized TSP avidly binds SS-RBCs under low shear conditions, soluble TSP did not bind SS-RBCs as detected by flow cytometry (Fig 5A). While this study cannot rule out weak TSP binding to SS-RBCs that did not tolerate the preparative washes, the tenacious adhesion of SS-RBCs observed in the flow adhesion chambers was clearly not present. Additionally, soluble TSP did not inhibit SS-RBC adhesion to immobilized TSP (Fig 5B). This suggests that immobilization of TSP on a matrix is required to expose the adhesive epitope within TSP that recognizes SS-RBCs. Because proteins binding to plastic may not accurately mimic in vivo conditions, TSP immobilized on a fibrinogen matrix was also tested. TSP-immobilized on fibrinogen bound SS-RBCs (mean 189 RBCs/mm2, N = 2), while the fibrinogen matrix alone promoted minimal SS-RBC adhesion (mean 6 RBCs/mm2, N = 2).

Soluble TSP does not bind SS-RBCs. Washed SS-RBCs were incubated with purified TSP (1.4 mg/mL) in the presence of 1 mmol/L Ca2+ for 30 minutes, 37°C. Treated RBCs were incubated with the nonblocking anti-TSP MoAb A4.1 (SS1 + TSP, SS2 + TSP), isotype-specific control MoAb MBC 45.7 (Control), or a positive control MoAb directed against glycophorin C (glycophorin C), followed by FITC-conjugated anti-mouse MoAb, and bound TSP detected by flow cytometry. The above data are representative of six separate experiments. (B) Washed SS-RBCs were incubated with purified soluble TSP (100 μg/mL) for 30 minutes at 37°C before performing the flow adhesion assay over immobilized TSP as described above (N = 3).

Soluble TSP does not bind SS-RBCs. Washed SS-RBCs were incubated with purified TSP (1.4 mg/mL) in the presence of 1 mmol/L Ca2+ for 30 minutes, 37°C. Treated RBCs were incubated with the nonblocking anti-TSP MoAb A4.1 (SS1 + TSP, SS2 + TSP), isotype-specific control MoAb MBC 45.7 (Control), or a positive control MoAb directed against glycophorin C (glycophorin C), followed by FITC-conjugated anti-mouse MoAb, and bound TSP detected by flow cytometry. The above data are representative of six separate experiments. (B) Washed SS-RBCs were incubated with purified soluble TSP (100 μg/mL) for 30 minutes at 37°C before performing the flow adhesion assay over immobilized TSP as described above (N = 3).

DISCUSSION

Using controlled proteolysis of TSP, we have shown that maintaining the integrity of the 20-kD carboxy-terminal segment of TSP is essential for binding to sickle erythrocytes. This region of TSP contains the cell-binding domain that recognizes platelets, human melanoma cells, and many other transformed cell lines.19 Using overlapping serial peptide sequences throughout the cell-binding domain33 followed by subsequencing the active sites,19 Kosfeld and Frazier have identified two adhesive peptide sequences, termed 4N1K and 7N3, that share the VVM amino acid motif. Although these adhesive sites are important for binding to platelets and multiple transformed cell lines, we found that neither of these adhesive peptides contributed to SS-RBC adhesion. In agreement, the TSP MoAb C6.7, which binds the cell-binding domain and inhibits the binding of platelets and transformed cells to these adhesive sites, had no blocking activity for SS-RBC adhesion. These data argue that SS-RBCs recognize a novel adhesive site within the 20-kD carboxy-terminal TSP cell-binding domain that is destroyed by proteolytic cleavage.

Alternatively, because the C-terminal 20-kD fragment remains disulfide linked to the 120-kD fragment, the proteolytic cleavage may directly destroy the adhesive epitope or essential interactions between the 20-kD and 120-kD TSP fragments. In this way, the cleavage of the cell-binding domain abolishes a critical conformational structure of the 20-kD fragment, the 120-kD fragment or a more distant region of TSP. Thus, SS-RBCs could be binding to a site other than the TSP cell-binding domain. However, the presence of the intact, uncleaved cell binding domain must be required for the proper conformational presentation of the alternative region of TSP. Additionally, because MoAbs directed against the heparin-binding domain and the type 1 repeats also failed to affect SS-RBC adhesion, no alternative sites on TSP that bind SS-RBCs were identified in this study.

The RGD peptide, which inhibits the binding of integrin receptors to TSP, also did not significantly inhibit SS-RBC adhesion compared with the control inactive peptide in this study. This is in contrast to other studies where the RGD peptide has been observed to inhibit SS-RBC adhesion to cytokine-treated35 or TSP-treated23endothelial cells. The differences between these results are likely due to distinct adhesive interactions occurring between SS-RBCs and either activated endothelial cells, TSP bound to endothelial cells, or immobilized TSP. Additionally, we25and others26 have previously reported that both OKM-5, a murine anti-CD36 MoAb, which blocks TSP binding to CD36, and the TSP type 1 repeat peptide, CSVTCG, which blocks the interaction of TSP with CD36, failed to inhibit the binding of SS-RBCs to immobilized TSP. These data would argue against other known adhesive TSP regions participating in SS-RBC adhesion to immobilized TSP.

The binding of TSP to SS-RBCs appears to be sensitive to conformational changes. This was evident by both the effect of divalent cation chelators on SS-RBC adhesion to TSP and the differences in binding activity between soluble and immobilized TSP. The conformation of both the Ca2+-binding domain and the cell-binding domain are affected by divalent cations.22,36 When Ca2+ is removed, the globular cell-binding domain unfolds and both the cell-binding domain and the Ca2+-binding domain are more sensitive to proteolytic cleavage.36,37 Because the removal of Ca2+ can destabilize disulfide bonds and result in extensive thiol-disulfide exchange, especially in the Ca2+-binding domain, some conformational changes are irreversible.38 Therefore, it is interesting that the EDTA-induced inhibition of SS-RBC adhesion to TSP was fully reversed after repletion of Ca2+.

Our observations that soluble TSP neither bound SS-RBCs nor inhibited the adhesion of SS-RBCs to immobilized TSP lend further support for a conformation-dependent epitope that is only expressed on TSP after binding to a matrix. Similar findings have been reported for other adhesive molecules such as fibrinogen, which is not recognized by the integrin αIIbβIII on resting platelets unless it binds to a matrix with an associated conformational change.22 Our observation that TSP immobilized on wells coated with fibrinogen also supported SS-RBC adhesion suggests that TSP within a more natural extracellular matrix will likely bind SS-RBCs. Alternatively, the high density of adhesive epitopes, resulting from coating high concentrations of purified TSP onto a surface, may optimize its affinity for SS-RBCs. Additionally, the finding by Barabino et al,39 that von Willebrand factor can bind to TSP and block SS-RBC adhesion, provides evidence that the adhesive epitope on immobilized TSP that recognizes sickle RBCs is complex and can be modulated by plasma and neighboring extracellular matrix proteins.

Two groups have previously reported that SS-RBCs bind to endothelial cells after the addition of soluble TSP.23,24 In these studies, the adhesion of the sickle RBCs to the endothelial cells was proposed to involve CD36 on the surface of sickle cells binding to CSVTG within the type 1 repeats of TSP that was attached to an adhesive receptor on the endothelial cell. Our observation that soluble TSP does not bind sickle RBCs suggests that the attachment of the TSP to the endothelial cells may induce a conformational change in TSP that permits it to bind to SS-RBCs. However, the binding of sickle RBCs to TSP bound to endothelial cells likely acts through different mechanisms compared with SS-RBC adhesion to immobilized TSP. Neither CD36 nor the type 1 repeats of TSP appear to be involved in the adhesion of SS-RBCs to immobilized TSP.25,26 Additionally, while the reports of sickle cell adhesion to endothelial cells via TSP show a reticulocyte predominant subpopulation of RBCs binding,23 24 we find that the SS-RBCs that bind to immobilized TSP under low shear flow conditions are not enriched for reticulocytes (unpublished observations, November 1996). Thus, it is likely that SS-RBC adhesion to intact endothelial cells versus extracellular matrix involves diverse adhesive/ligand interactions and conformational requirements.

In studying myoblast adhesion to immobilized TSP, Adams and Lawler20 reported that myoblasts bound to the 140-kD TSP fragment, but not to TSP fragments containing the heparin-binding domain, or the type 1 and 2 repeats, and that this adhesion was not affected by MoAb C6.7. These results are identical to those found in this study for SS-RBC adhesion to surface-bound TSP. Additionally, they found that either high-molecular-weight dextran sulfate or chondroitin sulfate A inhibited the adhesion of myoblasts to TSP and proposed that chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans on the myoblast surface were likely contributing to the adhesive phenotype.20 We25 and others26 have previously reported that the binding of SS-RBCs to immobilized TSP is similarly inhibited by either high-molecular-weight dextran sulfate or chondroitin sulfate A, and we25 proposed that sulfated glycolipids may contribute to the SS-RBC adhesion. These data suggest that analogous mechanisms may be contributing to the adhesion of either myoblasts or sickle RBCs to immobilized TSP. It would be interesting to postulate that an aberrant sulfated moiety in the sickle RBC membrane may be binding to TSP through a mechanism that evolved for the inherent control of myoblast adhesion to matrix-bound TSP.

It is not known whether the adhesion of SS-RBCs to TSP contributes to vaso-occlusive crises in sickle cell disease in vivo. However, identification of the characteristics of SS-RBC adhesion will likely improve our understanding of vaso-occlusive events in sickle cell disease and may potentially result in improved therapy for this disorder. The data in this study provide evidence for a unique conformation- or valence-dependent adhesive site within the 20-kD carboxy-terminal region of TSP required for the adhesion of SS-RBCs to the subendothelial matrix protein TSP under conditions of flow in vitro. Further characterization of this region within TSP that binds the SS-RBCs and conditions that will inhibit this interaction will further our understanding of RBC-adhesive ligand interactions and may provide insight into the pathophysiology of vaso-occlusion in sickle cell disease.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank William A. Frazier (Washington University, St Louis, MO) for the gifts of MoAbs and peptides that were used in this study, as well as for careful review and useful suggestions regarding the manuscript. We also thank Evelyn Brown and Gwendolyn Lea for their assistance in obtaining blood samples for this study.

Supported by Public Health Services Grants No. K08-HL02858 (C.A.H.) and Clinical Research Center Grant No. RR00058 from the National Institutes of Health.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to Cheryl A. Hillery, MD, Blood Research Institute, The Blood Center of Southeastern Wisconsin, PO Box 2178, Milwaukee, WI 53201-2178; e-mail: chillery@bcsew.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal