We examined the types of Epstein-Barr virus–associated nuclear antigen-1 (EBNA-1) gene carboxy (C)-terminal mutations occurring in Hodgkin’s disease (HD) and reactive tissues from two different geographic regions. Previously reported EBNA-1 C-terminal region amino acid sequence variants, based on the amino acid at codon 487, include Prototype (P)-ala, which is found in the B95.8-derived prototype virus, P-thr, Variant (V)-leu, V-val, and V-pro. Using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to amplify portions of the EBNA-1 gene, followed by DNA sequencing, we found a single EBNA-1 gene sequence variant in each tissue, whether reactive or neoplastic and whether from Brazil or the United States. Variant EBNA-1 gene sequences were more common in both neoplastic and non-neoplastic tissues from different geographic areas than the so-called prototype sequence. In the 17 Brazilian HD cases, 4 cases had P-thr variants and 13 had V-leu variants. In the six reactive tissues from Brazil, one had a P-ala variant, two had P-thr variants, and three had V-leu variants. In the 12 American HD cases, 2 had P-ala variants, 6 had P-thr variants, and 4 had V-leu variants. The 11 American reactive tissues included 2 P-ala variants, 5 P-thr variants, and 4 V-leu variants. In both countries, there were similar variant EBNA-1 sequences present in normal tissues and HD cases. Compared with the P-ala and P-thr cases, the V-leu cases were more likely to have the 30-bp latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1) gene deletion (P = 0.0075). In addition, cases of HD with the V-leu were statistically associated with a substitution of asparagine for glutamine at codon 322 of the C-terminal portion of the LMP1 gene. Our results suggest that any variation in EBNA-1 gene sequence is caused by a polymorphism present in pre-existing viral strains in the underlying population, and not a mutation occurring during oncogenesis.

THE EPSTEIN-BARR VIRUS (EBV) is associated with a number of malignancies, including Hodgkin’s disease (HD), non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas, and nasopharyngeal carcinoma.1-4 An association between EBV and HD had long been suspected from early epidemiological and serological studies.5-8 Demonstration of EBV genomic DNA in HD was first reported in 1987.9 Subsequent in situ hybridization studies localized the virus to the Reed-Sternberg cells and variants, which are the presumed neoplastic component of HD.1 10-12Approximately 40% to 50% of cases of classical HD occurring in immunocompetent individuals are EBV-associated. In EBV-positive HD cases, the EBV is found in nearly all of the Reed-Sternberg cells, regardless of methodology.

In an effort to elucidate the pathogenesis of these EBV-related HD cases, investigators have examined EBV genes with oncogenic potential: latent membrane protein (LMP), EBV-associated nuclear antigen-1 (EBNA-1), and EBNA-2. A deleted LMP1 gene variant, initially thought to be important to the pathogenesis of HD, has been reported in equal frequency in cases of EBV-associated HD and normal tissues in different ethnic populations.13-18 This observation suggests that this deletion may not be relevant in the pathogenesis of EBV-associated HD, at least in immunocompetent patients.

Immunohistochemical studies have detected EBNA-1 protein in cases of EBV-associated HD.19 Initial molecular studies of EBNA-1 reported the prototype EBNA-1 gene to be extremely rare in malignant tissues.20 In contrast, unique variant EBNA-1 gene sequences have been found in different malignancies, suggesting that some EBNA-1 subtypes may play a role in tumorigenesis.21Furthermore, investigators have also reported the presence of both prototype and variant EBNA-1 gene sequences in oral secretions and peripheral blood cells from normal patients, with an EBNA-1 subtype pattern and frequency different than those reported in various malignancies.20 However, in a previous study of EBNA-1 gene sequences in gastric carcinoma, we found the prevalence of variant sequences in the tumor tissues to be similar to that of reactive tissues, and also, that each tissue, whether benign or malignant, harbored a single EBNA-1 subtype.22

Because there are no reported data on EBNA-1 gene deletions in HD, we examined the different types of EBNA-1 gene carboxy (C)-terminal mutations occurring in HD and non-HD reactive tissues from patients living in two different geographic regions. Our results show that (1) variant EBNA-1 gene sequences are more prevalent in non-neoplastic tissues than the so-called prototype sequence; (2) similar variant EBNA-1 sequences are present in normal tissues and HD cases from Brazil, suggesting that any variation is a result of a polymorphism and not a mutation; (3) the neoplastic tissues from the United States also have similar EBNA-1 gene sequences as their reactive counterparts, and furthermore, are similar to those of the Brazilian tissues, showing that the different ethnic groups may have similar types of polymorphisms; (4) only one EBNA-1 subtype is present in each tissue type, regardless of geographic origin; and (5) the prevalence of the EBNA-1 gene subtypes is statistically significantly different, depending on the presence or absence of the LMP1 gene deletion variant and the presence or absence of a polymorphism at codon 322 of the C-terminal protion of the LMP1 gene.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cases.

We studied 29 cases of EBV-associated HD, including 17 cases from Brazil and 12 cases from the United States. We also studied 17 reactive lymphoid tissues, including 6 Brazilian cases of either normal tonsil or nonspecific tonsillitis, 3 American tonsillar cases of reactive hyperplasia, and 8 American HD cases in which the Reed-Sternberg cells were negative for EBV Epstein-Barr virus–encoded RNA (EBER), but rare small lymphocytes were EBER-positive. The clinical aspects, histological features, EBV EBER data, the results of LMP1 immunohistochemistry and gene deletion studies, and the EBV type (Type A or B) have been previously reported.13 The EBNA-1 gene sequences of the American reactive lymphoid tissues have been previously reported.22 EBV serological data were not available for any of the patients.

Polymerase chain reaction studies for the C-terminal of the EBNA-1 gene.

The EBNA-1 genotype was analyzed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification and subsequent sequence analysis of the C-terminal region of EBNA-1, which has been previously shown to contain most of the substitutions seen in the reported variant subtypes.20,21 23 For each case, genomic DNA was extracted from 5-μm sections cut from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue blocks, using 0.2 mg/mL proteinase K digestion buffer overnight, followed by denaturation by boiling. PCR studies were performed with 2 μL of extracted DNA in a 30-μL mixture containing 50 mmol/L KCl, 10 mmol/L Tris buffer (pH 8.3), 50 μmol/L of each deoxynucleotide triphosphate, 2.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 1 U of Taq polymerase (Perkin Elmer, Foster City, CA), and 20 pmol of each primer. Two 24-base oligonucleotide primers were used: C1, 5′-GAAATTTGAGAACATTGCAGAAGG-3′ and C2, 5′-GGGTCCAGGGGCCATTCCAAA-3′. After an initial denaturation for 3 minutes at 95°C, 45 amplification cycles were performed as follows: denaturing at 94°C for 30 seconds, annealing at 58°C for 30 seconds, and extension at 72°C for 40 seconds. A final extension at 72°C for 3 minutes completed the PCR amplification. The PCR setup and the post-PCR work were performed in separated laboratories to minimize the possibility of contamination.

PCR studies for the LMP1 gene deletion region.

Using genomic DNA as extracted above, the C-terminal region of the LMP1 gene deletion region was sequenced as above, using two 20-base oligonucleotide primers: 5′-GGAAATGATGGAGGCCCTCC-3′ and 5′-GTAGCTTAGCTGAACTGGGC-3′. For a small subset of samples in which the initial PCR step yielded no visible gel products, nested PCR amplification was performed using the following two sets of 20-base oligonucleotide primers: 5′-CGGAAGAGGTGGAAAACAAA-3′ and 5′-GTGGGGGTCGTCATCATCTC-3′. The PCR conditions and amplification strategies were identical to those listed above.

DNA sequencing.

Thirty microliters of the PCR products were run on a 2% agarose gel, and the product bands were cut out, purified using a Qiaex gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), and resuspended in 30 μL of water. The products were sequenced with an AmpliCycle sequencing kit (Perkin Elmer), using the manufacturer’s recommended conditions. The products of the sequencing reaction were then separated by gel electrophoresis, dried, and exposed to film. The gel consisted of 7 mol/L urea and 8% polyacrylamide.

RESULTS

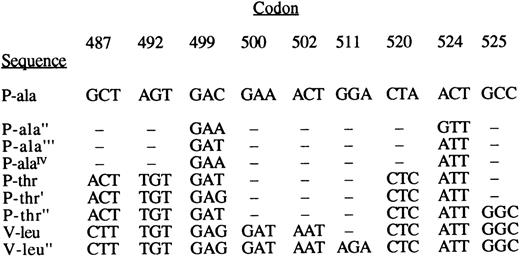

In this report, we use terminology introduced by Gutierrez et al, who classified EBV into five subtypes, based on the EBNA-1 amino acid sequence in the C-terminal region.20 They named the EBNA-1 subtypes according to the amino acid at codon 487 (Fig1). Two closely related prototype strains were identified, named by their difference in the amino acid at codon 487 (Prototype [P]-ala, with alanine at codon 487, is found in the B95.8-derived virus; P-thr differs by the presence of threonine at codon 487). They identified three additional EBNA-1 variants (V), termed V-pro, V-leu, and V-val, because of proline, leucine, or valine, respectively, at codon 487 instead of alanine. In addition, we continue terminology used in our previous report of EBNA-1 gene sequences in gastric carcinoma.22

Detailed sequence data of the carboxy fragment of EBNA-1 amplified from Brazilian and American EBV-associated Hodgkin’s disease and non–EBV-associated Hodgkin’s disease and reactive tissues.

Detailed sequence data of the carboxy fragment of EBNA-1 amplified from Brazilian and American EBV-associated Hodgkin’s disease and non–EBV-associated Hodgkin’s disease and reactive tissues.

Using PCR to amplify fragments of the EBNA-1 gene, followed by gene sequencing, we identified EBNA-1 gene sequence variants in all 17 cases of known EBV-positive HD from Brazil (Table1). Each case contained only a single EBNA-1 gene sequence. None of the Brazilian cases had the prototype P-ala sequence. Three of the HD cases had a gene sequence that resulted in the same amino acid sequence published by Gutierrez as P-thr.20 The gene sequence was identical to the P-thr sequence detected in clones of a single nasal lymphoma in another report from the same group.24 Compared with the prototype P-ala EBNA-1 gene, the P-thr sequence differed by three amino acid substitutions, at codons 487, 492, and 524, and two silent base changes at codons 499 and 520. Another case had the same changes as P-thr, with an additional point mutation at codon 525; we named this P-thr". This variant sequence was also identified in a previous study of nasal lymphomas.24 Twelve of the Hodgkin’s cases from Brazil had an EBNA-1 gene sequence that differed from the prototype P-ala by eight codon changes, including seven amino acid substitutions at codons 487, 492, 499, 500, 502, 524, and 525, and a silent mutation at codon 520. These 12 nonprototype cases had the same amino acid sequence as the V-leu variant previously described by Gutierrez et al,20and furthermore, they had the same gene sequence identified as V-leu in the nasal lymphoma study of Gutierrez.24 The final Brazilian HD case had an EBNA-1 gene sequence that was similar to V-leu, with an additional point mutation at codon 511. We named this variant as V-leu". This variant has not been previously described.

EBNA-1 Subtypes Identified in Cases of EBV-Positive Hodgkin’s Disease and Reactive Lymphoid Tissues

| . | EBNA-1 Subtype . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| P-ala & Variants . | P-thr & Variants . | V-leu & Variants . | |

| Brazilian | |||

| Hodgkin’s disease | 0 | 4 | 13 |

| Reactive | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| American | |||

| Hodgkin’s disease | 2 | 6 | 4 |

| Reactive | 2 | 5 | 4 |

| Total | 5 | 17 | 24 |

| . | EBNA-1 Subtype . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| P-ala & Variants . | P-thr & Variants . | V-leu & Variants . | |

| Brazilian | |||

| Hodgkin’s disease | 0 | 4 | 13 |

| Reactive | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| American | |||

| Hodgkin’s disease | 2 | 6 | 4 |

| Reactive | 2 | 5 | 4 |

| Total | 5 | 17 | 24 |

The six reactive tissues from Brazil also each had a single EBNA-1 gene sequence that differed from the P-ala prototype gene sequence. One reactive tissue differed from the P-ala prototype by two amino acid substitutions at codons 499 and 524, and we named this as P-alaIV. This variant has also not been previously described. Two reactive Brazilian tissues had the P-thr EBNA-1 gene sequence. The V-leu EBNA-1 gene sequence was identified in the remaining three reactive Brazilian tissues.

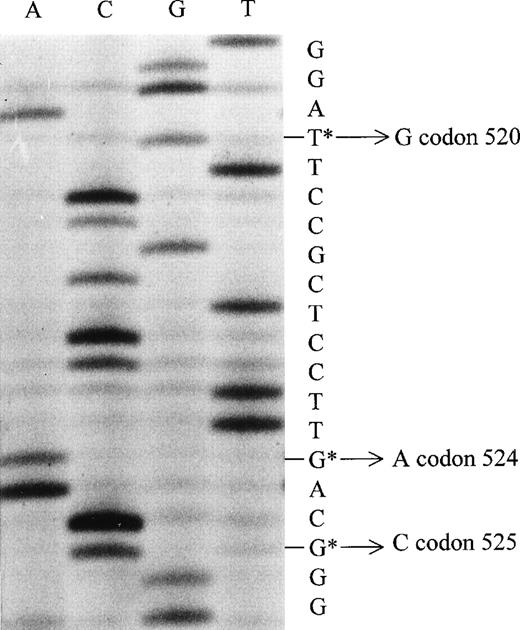

Of the 12 cases of North American HD, only one case had the prototype P-ala gene sequence. Another case had an EBNA-1 gene sequence with two amino acid substitutions at codons 499 and 524, which was named P-ala". This sequence was previously observed in our study of EBNA-1 gene sequences in gastric carcinomas.22 Six American HD cases had the P-thr amino acid sequence, and four others had the V-leu amino acid sequence (Fig 2).

This is a sequence gel of one of the cases of North American Hodgkin’s disease; this is the minus strand of the V-leu variant. This shows a change from thymine to guanine at codon 520, from guanine to alanine at codon 524, and from guanine to cytosine at codon 525.

This is a sequence gel of one of the cases of North American Hodgkin’s disease; this is the minus strand of the V-leu variant. This shows a change from thymine to guanine at codon 520, from guanine to alanine at codon 524, and from guanine to cytosine at codon 525.

None of the 11 reactive American tissues contained the prototype P-ala gene sequence. Two of the reactive tissues each had a different P-ala variant of the prototype sequence, including P-ala" and P-ala‴, both of which were observed in our previous study of EBNA-1 gene sequences in gastric carcinomas.22 Four other reactive American tissues had the same P-thr gene sequence that was identified in three cases of Brazilian HD, and another patient had a different variant of P-thr, with four amino acid substitutions at codons 487, 492, 499, and 524, and a silent base change at codon 520, which we named as P-thr′. This P-thr′ sequence was previously reported in a study of nasal lymphomas.24 Another four patients had the V-leu sequence.

For all of these tissues, the most frequent substitutions were identified at codons 499 and 524. Identical substitutions were found at both of these codons in all of the Brazilian and American tissues, whether reactive or malignant. Other frequently substituted sites were codons 492 and 520. Both were affected with identical substitutions in the Brazilian and American tissues in equally high frequency. Codons 500, 502, and 525 were less frequent sites of mutation; these were seen in much higher frequency in the Brazilian tissues when compared with the American tissues. Again, all of the substitutions were identical. Codon 511 was the site of mutation in a single Brazilian HD case.

Table 2 shows the frequency of the LMP1 gene deletion with the different EBNA-1 gene sequence variants. Seventy-three percent of the cases previously shown to have the LMP1 gene deletion variant13 had the V-leu EBNA-1 subtype (16 of 22), whereas 67% of cases previously shown to have the nonmutated LMP1 gene had one of the prototype EBNA-1 gene sequence variants. This difference was statistically significant (P = .0075), even when comparing the V-leu cases with P-ala and P-thr cases separately (P < .03).

Frequency of LMP Gene Deletion Variant and EBNA-1 Subtype

| EBNA-1 Subtype . | LMP Gene Type . | |

|---|---|---|

| Wild Type . | Deletion Variant . | |

| P-ala | 4 | 1 |

| P-thr | 12 | 5 |

| V-leu | 8 | 16 |

| Total | 24 | 22 |

| EBNA-1 Subtype . | LMP Gene Type . | |

|---|---|---|

| Wild Type . | Deletion Variant . | |

| P-ala | 4 | 1 |

| P-thr | 12 | 5 |

| V-leu | 8 | 16 |

| Total | 24 | 22 |

Table 3 shows the EBV LMP1 deletion region polymorphisms for the 46 cases. The 2-bp change resulting in substitution of asparagine (Asn) for glutamine at codon 322 of the C-terminal portion of the LMP1 gene was found to be statistically significant more frequently in tissues that had the V-leu EBNA-1 subtype (14 of 21, 67%). Wildtype LMP1 was more frequently identified in tissues with the P-thr EBNA-1 subtype; this was statistically significant (10 of 13, 77%). Seven of 10 (70%) Brazilian HD cases previously shown to have the V-leu EBNA-1 subtype had the Asn amino acid substitution for glutamine. In contrast, none of the four Brazilian HD cases previously shown to have the P-thr EBNA-1 subtype had any LMP deletion region polymorphisms. This difference was statistically significant (P < 0.02). Furthermore, three of four (75%) American HD cases that were previously shown to have the V-leu EBNA-1 subtype also had the Asn amino acid substitution at codon 322 of the C-terminal portion of the LMP1 gene. In contrast, only one of six P-thr American HD cases (17%) had the Asn amino acid substitution, with the other five P-thr cases consisting of three wildtype LMP1 cases and two cases with a single base pair substitution. Four of the seven (57%) reactive cases (both countries) previously identified as V-leu also had the Asn amino acid substitution, in contrast to three of five (60%) reactive P-thr cases having the wildtype LMP1 gene. In these reactive cases, the tendency for a particular EBNA-1 subtype to have a specific LMP1 deletion region polymorphism was not statistically significant, perhaps because of the low numbers of cases.

EBV LMP1 Gene Deletion Region Polymorphisms

| Case . | Diagnosis . | EBNA-1 Subtype . | LMP Gene Deletion . | 322 . | 325 . | 326 . | 327 . | 328 . | 333 . | 334 . | 335 . | 337 . | 338 . | 342 . | 344 . | 348 . | 349 . | 351 . | 352 . | 354 . | 355 . | 356 . | 361 . | 366 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B95.8 | CAA Gln | GAA Glu | GAG Glu | GTT Val | GAA Glu | CAG Gln | CAG Gln | GGC Gly | CCT Pro | TTG Leu | GGA Gly | GGC Gly | CAT His | GAT Asp | GGC Gly | CAT His | GGC Gly | GGT Gly | GAT Asp | ACG Thr | TCT Ser | |||

| 1 | Br HD | V-leu | Yes | AAT Asn | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | — | AGC Ser | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ACT Thr |

| 2 | Br HD | P-thr | No | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | GAC | — | ACT Thr | |

| 3 | Br HD | P-thr | No | — | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | CGT Arg | — | TGT Cys | — | ACA | ACT Thr |

| 4 | Br HD | V-leu | Yes | AAT Asn | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ACT Thr |

| 5 | Br HD | V-leu | No | — | — | — | — | GGA Gly | — | — | — | — | — | GGT | — | CGT Arg | AAT Asn | AGC Ser | CGT Arg | — | — | — | — | ACT Thr |

| 6 | Br HD | V-leu | Yes | AAT Asn | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ACT Thr |

| 7 | Br HD | V-leu» | No | GAA Glu | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ACA | ACT Thr |

| 8 | Br HD | V-leu | Yes | AAT Asn | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ACT Thr |

| 9 | Br HD | V-leu | No | GAA Glu | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | CGT Arg | — | — | — | ACA | ACT Thr |

| 10 | Br HD | P-thr» | No | — | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | CGT Arg | — | — | — | ACA | ACT Thr |

| 11 | Br HD | V-leu | No | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | GGT | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ACT Thr |

| 12 | Br HD | V-leu | Yes | AAT Asn | — | — | GAT Asp | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ACT Thr |

| 13 | Br HD | V-leu | Yes | AAT Asn | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ACT Thr |

| 14 | Br HD | V-leu | No | — | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | CGT Arg | — | — | — | ACA | ACT Thr |

| 15 | Br HD | V-leu | Yes | AAT Asn | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ACA | ACT Thr |

| 16 | Br HD | P-thr | Yes | — | — | — | GAT Asp | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ACA | ACT Thr |

| 17 | Br HD | V-leu | No | ? | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | GGT | — | — | — | — | CGT Arg | — | — | — | — | ACT Thr |

| 18 | Br React | V-leu | Yes | AAT Asn | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ACT Thr |

| 19 | Br React | V-leu | Yes | — | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ACT Thr |

| 20 | Br React | P-alaIV | No | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 21 | Br React | P-thr | No | GAA Glu | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | GGT Gly | — | CGT Arg | — | — | — | ACA | ACT Thr |

| 22 | Br React | V-leu | Yes | AAT Asn | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | TCT Ser | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ACT Thr |

| 23 | Br React | P-thr | No | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | AAT Asn | — | — | AAT Asn | — | — | GAC | — | ACT Thr |

| 24 | Am HD | V-leu | Yes | AAT Asn | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ACT Thr | |

| 25 | Am HD | P-thr | No | — | — | — | — | CAA Gln | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | GCT Ala | — | — | — | — | — | GAC | — | ACT Thr |

| 26 | Am HD | P-thr | No | — | — | — | — | CAA Gln | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | GCT Ala | — | — | — | — | — | GAC | — | ACT Thr |

| 27 | Am HD | P-thr | No | CAC His | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | CGT Arg | AGC Ser | — | AAT Asn | ACA | ACT Thr |

| 28 | Am HD | P-thr | Yes | AAT Asn | — | GAC Asp | — | — | — | AGG | AGC Ser | TCT Ser | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ACT Thr |

| 29 | Am HD | V-leu | Yes | AAT Asn | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ACT Thr |

| 30 | Am HD | P-thr | No | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | GAC | — | ACT Thr |

| 31 | Am HD | P-thr | No | GAA Glu | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | CGT Arg | — | — | — | ACA | ACT Thr |

| 32 | Am HD | V-leu | No | — | GAG | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | GGT | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | GCT |

| 33 | Am HD | P-ala | No | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 34 | Am HD | V-leu | Yes | AAT Asn | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | — | GGT | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ACT Thr |

| 35 | Am HD | P-ala» | No | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | GAC | — | ACT Thr |

| 36 | Am React | P-ala» | No | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 37 | Am React | P-ala′» | Yes | AAT Asn | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ACT Thr |

| 38 | Am React | V-leu | Yes | AAT Asn | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ACT Thr |

| 39 | Am React | P-thr′ | Yes | AAT Asn | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 40 | Am React | V-leu | Yes | AAT Asn | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ACT Thr |

| 41 | Am React | V-leu | No | — | — | — | — | — | AGG Arg | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | CGT Arg | — | — | — | ACA | ACT Thr |

| 42 | Am React | P-thr | Yes | AAT Asn | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ACT Thr |

| 43 | Am React | P-thr | No | GAA Glu | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | GTC Val | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | GCT Ala | — | CGT Arg | — | — | — | ACA | ACT Thr |

| 44 | Am React | P-thr | No | — | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | — | — | TGT Cys | — | ACA | ACT Thr |

| 45 | Am React | P-thr | Yes | AAT Asn | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ACT Thr |

| 46 | Am React | V-leu | Yes | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Case . | Diagnosis . | EBNA-1 Subtype . | LMP Gene Deletion . | 322 . | 325 . | 326 . | 327 . | 328 . | 333 . | 334 . | 335 . | 337 . | 338 . | 342 . | 344 . | 348 . | 349 . | 351 . | 352 . | 354 . | 355 . | 356 . | 361 . | 366 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B95.8 | CAA Gln | GAA Glu | GAG Glu | GTT Val | GAA Glu | CAG Gln | CAG Gln | GGC Gly | CCT Pro | TTG Leu | GGA Gly | GGC Gly | CAT His | GAT Asp | GGC Gly | CAT His | GGC Gly | GGT Gly | GAT Asp | ACG Thr | TCT Ser | |||

| 1 | Br HD | V-leu | Yes | AAT Asn | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | — | AGC Ser | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ACT Thr |

| 2 | Br HD | P-thr | No | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | GAC | — | ACT Thr | |

| 3 | Br HD | P-thr | No | — | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | CGT Arg | — | TGT Cys | — | ACA | ACT Thr |

| 4 | Br HD | V-leu | Yes | AAT Asn | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ACT Thr |

| 5 | Br HD | V-leu | No | — | — | — | — | GGA Gly | — | — | — | — | — | GGT | — | CGT Arg | AAT Asn | AGC Ser | CGT Arg | — | — | — | — | ACT Thr |

| 6 | Br HD | V-leu | Yes | AAT Asn | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ACT Thr |

| 7 | Br HD | V-leu» | No | GAA Glu | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ACA | ACT Thr |

| 8 | Br HD | V-leu | Yes | AAT Asn | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ACT Thr |

| 9 | Br HD | V-leu | No | GAA Glu | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | CGT Arg | — | — | — | ACA | ACT Thr |

| 10 | Br HD | P-thr» | No | — | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | CGT Arg | — | — | — | ACA | ACT Thr |

| 11 | Br HD | V-leu | No | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | GGT | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ACT Thr |

| 12 | Br HD | V-leu | Yes | AAT Asn | — | — | GAT Asp | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ACT Thr |

| 13 | Br HD | V-leu | Yes | AAT Asn | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ACT Thr |

| 14 | Br HD | V-leu | No | — | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | CGT Arg | — | — | — | ACA | ACT Thr |

| 15 | Br HD | V-leu | Yes | AAT Asn | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ACA | ACT Thr |

| 16 | Br HD | P-thr | Yes | — | — | — | GAT Asp | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ACA | ACT Thr |

| 17 | Br HD | V-leu | No | ? | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | GGT | — | — | — | — | CGT Arg | — | — | — | — | ACT Thr |

| 18 | Br React | V-leu | Yes | AAT Asn | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ACT Thr |

| 19 | Br React | V-leu | Yes | — | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ACT Thr |

| 20 | Br React | P-alaIV | No | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| 21 | Br React | P-thr | No | GAA Glu | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | GGT Gly | — | CGT Arg | — | — | — | ACA | ACT Thr |

| 22 | Br React | V-leu | Yes | AAT Asn | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | TCT Ser | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ACT Thr |

| 23 | Br React | P-thr | No | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | AAT Asn | — | — | AAT Asn | — | — | GAC | — | ACT Thr |

| 24 | Am HD | V-leu | Yes | AAT Asn | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ACT Thr | |

| 25 | Am HD | P-thr | No | — | — | — | — | CAA Gln | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | GCT Ala | — | — | — | — | — | GAC | — | ACT Thr |

| 26 | Am HD | P-thr | No | — | — | — | — | CAA Gln | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | GCT Ala | — | — | — | — | — | GAC | — | ACT Thr |

| 27 | Am HD | P-thr | No | CAC His | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | CGT Arg | AGC Ser | — | AAT Asn | ACA | ACT Thr |

| 28 | Am HD | P-thr | Yes | AAT Asn | — | GAC Asp | — | — | — | AGG | AGC Ser | TCT Ser | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ACT Thr |

| 29 | Am HD | V-leu | Yes | AAT Asn | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ACT Thr |

| 30 | Am HD | P-thr | No | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | GAC | — | ACT Thr |

| 31 | Am HD | P-thr | No | GAA Glu | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | CGT Arg | — | — | — | ACA | ACT Thr |

| 32 | Am HD | V-leu | No | — | GAG | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | GGT | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | GCT |

| 33 | Am HD | P-ala | No | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 34 | Am HD | V-leu | Yes | AAT Asn | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | — | GGT | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ACT Thr |

| 35 | Am HD | P-ala» | No | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | GAC | — | ACT Thr |

| 36 | Am React | P-ala» | No | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 37 | Am React | P-ala′» | Yes | AAT Asn | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ACT Thr |

| 38 | Am React | V-leu | Yes | AAT Asn | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ACT Thr |

| 39 | Am React | P-thr′ | Yes | AAT Asn | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 40 | Am React | V-leu | Yes | AAT Asn | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ACT Thr |

| 41 | Am React | V-leu | No | — | — | — | — | — | AGG Arg | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | CGT Arg | — | — | — | ACA | ACT Thr |

| 42 | Am React | P-thr | Yes | AAT Asn | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ACT Thr |

| 43 | Am React | P-thr | No | GAA Glu | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | GTC Val | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | GCT Ala | — | CGT Arg | — | — | — | ACA | ACT Thr |

| 44 | Am React | P-thr | No | — | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | — | — | TGT Cys | — | ACA | ACT Thr |

| 45 | Am React | P-thr | Yes | AAT Asn | — | — | — | — | — | CGG Arg | — | — | TCG Ser | GGT | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ACT Thr |

| 46 | Am React | V-leu | Yes | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

Abbreviations: Am HD, American Hodgkin’s disease; Am React, American reactive tissues; Br HD, Brazilian Hodgkin’s disease; Br React, Brazilian reactive tissues.

As previously published, only four of the tissues had EBV Type B; the rest were Type A.13 Three of the four Type B tissues had the V-leu EBNA-1 gene sequence; the other had the P-ala" gene sequence. There was no statistically significant difference in EBV Type A or Type B, when compared with the different EBNA-1 gene sequence variants.

DISCUSSION

EBNA-1 is a nuclear antigen that is essential for the maintenance of the Epstein-Barr viral episome. It is also the only viral protein required for replication of the latent form of EBV.25,26Relative to the C-terminal region of the Epstein-Barr prototype virus B95.8, several variants of the EBNA-1 gene sequence have been identified.20-22,27 28 These variants have been reported in non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas, nasopharyngeal carcinomas, gastric carcinomas, and/or cell lines known to carry monoclonal EBV, in equal frequency in Type I and Type II EBV strains.

Our data on EBNA-1 gene sequences in HD and reactive tissues from Brazilian and American patients differ from previously published EBNA-1 gene sequence data in non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas and other malignancies in several ways. First, we found a single variant EBNA-1 sequence in each of the reactive tissues, in contrast to the finding of multiple EBNA-1 sequences in oral secretions and peripheral blood samples of normal patients by Gutierrez et al,20 and also in contrast to the finding of two clones of spontaneously derived EBV-containing B-cell lines, each with a different subtype, obtained from a single healthy individual by Wrightham et al.28 We hypothesize that this difference may be because of site-specific EBV reservoirs, with analysis of amplified DNA from oral secretions and peripheral blood lymphocytes allowing for sampling of viral reservoirs containing both free and cell-associated virus, whereas amplified DNA from tissue samples contains only cell-associated EBV.

Second, we found EBNA-1 gene sequences in reactive tissues that are similar to those in malignant tissues from the same ethnic population. This finding suggests that observed variations in EBNA-1 gene sequences are a result of polymorphisms present in the resident EBV strain(s) in a population and not caused by mutations occurring during pathogenesis. These results differ from those of Bhatia et al, for whom one variant subtype was seen only in Burkitt lymphoma cases and not in any samples of normal peripheral blood lymphocytes in two different ethnic groups.21 These results also differ from Gutierrez et al, who found different EBNA-1 sequence alterations in Hong Kong nasopharyngeal carcinomas than those detected in normal Hong Kong peripheral blood lymphocytes.20 However, these results are similar to our previous study of gastric carcinoma, in which the gene sequences in reactive and malignant tissues were identical or similar in the same ethnic population.22 In addition, in the study of Gutierrez et al, selected normal oral secretions from Hong Kong patients contained similar EBNA-1 amino acid sequences as the nasopharyngeal carcinoma tissues.20

Third, the EBNA-1 gene sequences found in Brazilian patients were similar to those found in American cases, showing that EBNA-1 gene sequences can be preserved in ethnically diverse but geographically separated populations. Previous studies also found similarities in prevalence and type of LMP gene deletions between these two geographically distinct populations.13

Interestingly, the EBNA-1 gene subtype was shown to be statistically significantly different, depending on whether the tissue had the LMP1 gene deletion or not. In addition, the presence of a specific LMP1 deletion region polymorphism was shown to be different depending on which EBNA-1 gene subtype the patient harbored. This was shown to be statistically significantly different for the cases of Brazilian and American HD, and the trend was also observed in cases of reactive tissues, whose numbers are too small to approach statistical significance. Although the mere presence of the LMP gene deletion is not indicative of a specific EBV strain, the sequence polymorphisms in the C-terminus of the LMP1 gene, an area that incorporates the deletion region, have been previously shown to be a reliable sequence for strain identification.29

Similar to other tissue studies, we identified only a single EBNA subtype in each tumor, regardless of ethnic origin. This is similar to previous studies of EBV-associated Burkitt lymphoma and nasopharyngeal carcinoma, in which the malignant tissues always contained a single EBNA-1 variant.20,21 However, our observation is in marked contrast to a recent report that documented multiple EBNA-1 subtypes in 33 of 39 nasal lymphomas.24 In that study, the presence of prototype EBNA-1 in conjunction with one to two variant EBNA-1 gene sequences was reported in all 33 nasal lymphomas. One could postulate that this difference in the observed number of EBNA-1 subtypes in tissue may also be site specific. One can easily imagine non-neoplastic EBV-infected oropharyngeal secretions “contaminating” nasopharyngeal biopsy samples, which must pass through the oropharynx or nasopharynx during the surgery; this would result in the amplification of multiple EBNA-1 variants. In contrast, tissues surgically removed from other anatomic sites not “passing through” the oropharynx or nasopharynx may result in amplification of only one cell-associated EBV subtype. However, our study also included some tissues from the nasopharynx, and thus, site-specific differences cannot fully explain the observed difference in number of EBNA-1 subtypes in tissue. We believe that the single variant strain in our cases reflects a “tissue-invasive” form of EBNA-1, and thus, it may be the strain most relevant to tumorigenesis.

We also found that variant EBNA-1 sequences are far more common in non-neoplastic tissues from different ethnic populations than the so-called prototype sequence. All of the reactive tissues had EBNA-1 C-terminal gene sequences that differed from the published B95.8 EBNA-1 gene sequence. Previous studies of healthy patients document predominance of the prototype EBNA-1 sequence, frequently in association with a variant EBNA-1 sequence; these studies were performed in body fluids and did not include non-neoplastic tissues. One group reported EBNA-1 antigen variants in 50% of lymphoblastoid cell lines established from normal EBV-seropositive volunteers from the United States and the United Kingdom.28 In contrast, another group reported the prototype P-ala amino acid sequence to be the most frequent EBNA-1 subtype in peripheral blood lymphocytes of healthy people, but the P-ala was usually present in conjunction with variant virus sequences.21 Based on our findings, we conclude that the incidence of the prototype sequence is not high in non-neoplastic solid tissues.

The reactive tissues from Brazil and the United States showed either a P-ala variant, P-thr or a P-thr variant, or V-leu or a V-leu variant. Previously identified EBNA-1 variants, V-val and V-pro, were not identified in any of the reactive cases.21 We propose that the lack of detectable V-pro and V-val subtypes indicates that these subtypes are not common in the resident population of these geographic areas.

In this study, all of the Brazilian and American HD cases had variant EBNA-1 gene sequences (P-ala variants, P-thr and variants, and V-leu and variants), regardless of whether they were from North or South America. This is similar to previous studies of cases of American and African Burkitt lymphomas, in which the P-ala sequence was found in a small minority of cases.21 This is also similar to the study of nasal lymphomas, in which all 39 tumors had at least one variant EBNA-1 gene sequence.24 In addition, one study reported nonprototypic EBNA-1 gene sequences in all seven Hong Kong nasopharyngeal carcinoma tissues, as well as in a nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell line and a B-lymphoblastoid cell line.27Furthermore, these results are similar to our previous study of EBNA-1 gene sequences in gastric carcinomas, in which variant EBNA-1 sequences were exclusively found in Japanese tumors and in 88% of American carcinomas.22 In the current study, we found only two EBNA-1 variants (P-thr" and V-leu") exclusively in malignant tissues. However, our numbers are too low (each in a different case of Brazilian HD) to draw any significant conclusions regarding these two EBNA-1 variants.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to Karen L. Chang, MD, Division of Pathology, City of Hope National Medical Center, 1500 E Duarte Rd, Duarte, CA 91010-0269.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal