Abstract

In response to thrombin and other extracellular activators, platelets secrete molecules from large intracellular vesicles (granules) to initiate thrombosis. Little is known about the molecular machinery responsible for vesicle docking and secretion in platelets and the linkage of that machinery to cell activation. We found that platelet membranes contain a full complement of interacting proteins—VAMP, SNAP-25, and syntaxin 4—that are necessary for vesicle docking and fusion with the plasma membrane. Platelets also contain an uncharacterized homologue of the Sec1p family that appears to regulate vesicle docking through its binding with a cognate syntaxin. This platelet Sec1 protein (PSP) bound to syntaxin 4 and thereby excluded the binding of SNAP-25 with syntaxin 4, an interaction critical to vesicle docking. As predicted by its sequence, PSP was detected predominantly in the platelet cytosol and was phosphorylated in vitro by protein kinase C (PKC), a secretion-linked kinase, incorporating 0.87 ± 0.11 mol of PO4 per mole of protein. PSP was also specifically phosphorylated in permeabilized platelets after cellular stimulation by phorbol esters or thrombin and this phosphorylation was blocked by the PKC inhibitor Ro-31-8220. Phosphorylation by PKC in vitro inhibited PSP from binding to syntaxin 4. Taken together, these studies indicate that platelets, like neurons and other cells capable of regulated secretion, contain a unique complement of interacting vesicle docking proteins and PSP, a putative regulator of vesicle docking. The PKC-dependent phosphorylation of PSP in activated platelets and its inhibitory effects on syntaxin 4 binding provide a novel functional link that may be important in coupling the processes of cell activation, intracellular signaling, and secretion.

THE PLATELET IS A specialized secretory cell that circulates in the blood and monitors the integrity of the vasculature. Injury to the blood vessel leads to extracellular stimulation of the platelet causing activation, changes in cell shape, secretion of intracellular granules, and platelet aggregation.1 These cellular events initiate a cascade of molecular interactions that cause thrombosis and begin the process of vascular repair. Because unregulated thrombosis can cause vascular occlusion with organ ischemia and infarction, many platelet effector molecules are sequestered within specialized intracellular vesicles such as the α granules and the dense granules. The α granules contain platelet-derived growth factor,2 the membrane adhesion molecule P-selectin,3,4 coagulation factor V,5 and the soluble adhesion molecules fibrinogen6 and thrombospondin,7 among others. The dense granules contain ADP and serotonin, which have an autocrine/paracrine effect in amplifying cellular activation and thrombosis.8

α and dense granule secretion is triggered by cell activation. In this highly regulated process, an agonist such as collagen, thrombin, or serotonin interacts with its cognate receptor on the cell membrane surface.9 Agonist stimulation of these receptors leads to activation of phospholipase C through a G-protein–coupled mechanism.8,10 Phospholipase C cleaves phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate to diacylglycerol (DAG) and inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3).11 The increase in IP3 causes an increase in intracellular calcium, which induces secretion.12 DAG activates protein kinase C (PKC),13 which interacts synergistically with the increasing amounts of intracellular calcium to amplify release of the contents of platelet granules.14 Recent studies have also indicated that PKC also plays a critical role in regulated secretion from synaptosomes, motor nerve endings, and pancreatic cells.15-17 However, the mechanisms through which activated PKC leads to secretion in platelets and other cells are still poorly understood.

Platelet granular secretion can be thought of as a specialized form of the vesicle trafficking and fusion that nearly all cells use to transport molecules. Studies of vesicular secretion in yeast, flies, worms, and mammals have led to models for the regulated secretion of neurotransmitters by neurons. One model, called the SNARE hypothesis, postulates that vesicles dock at the plasma membrane in preparation for fusion.18 In neurons, this docking is mediated by the specific interactions of a vesicle membrane protein, VAMP, with two plasma membrane receptors, SNAP-25 and syntaxin 1, in a SNARE complex.18 The interactions of these proteins appear to be specifically modulated by members of the Sec1p/unc-18 family, cytoplasmic proteins whose binding to syntaxin 1 excludes binding interactions with VAMP and SNAP-25.19

Platelets are uniquely suited for the study of triggered secretion because they have no nucleus, almost no Golgi apparatus, and minimal intracellular vesicle trafficking and synthesize relatively few proteins.20 Yet, comparatively little is known about the molecular components that mediate triggered secretion in platelets. We have identified a previously uncharacterized platelet Sec1protein (PSP) and gene that is homologous to the Sec1/unc-18family whose genes encode proteins that modulate vesicle docking through their interactions with the syntaxin proteins.21 We find that platelets contain a full complement of homologues of interacting molecules involved in vesicle docking and fusion in neurons and other secretory cells—syntaxin 4, VAMP, and SNAP-25. In platelets, PSP interacts with syntaxin 4 and is phosphorylated through the secretion-linked kinase PKC. This PKC-mediated phosphorylation inhibits the binding of PSP with syntaxin 4, providing a possible mechanistic linkage between the processes of cellular activation and cellular secretion.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Molecular Cloning of PSP

An antiplatelet antibody (described below) was used to screen 300,000 plaques from a λZAP (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) cDNA library constructed from transcripts of the human leukemic CCRF cell line.22 Plaques reacting with the antiplatelet antibody, but not the nonimmune antibody, were identified and purified to homogeneity by repetitive screening as described.23,24 The phagemid cDNA was isolated and both strands were sequenced (Sequenase; US Biochemical, Cleveland, OH).25 One cDNA represented the PSP gene described in this study; the 3 other genes isolated will form the basis for subsequent reports.

Polymerase Chain Reaction Cloning of Human Syntaxins

mRNA containing Poly(A) was obtained from the DAMI megakaryocytic cell line as we have described.23 cDNA was synthesized by standard techniques (c-Clone II; Clontech, Palo Alto, CA).24 Two degenerate primers were designed that were complementary to conserved regions of syntaxins 1 through 5. The primers contained an added EcoRI or HindIII restriction site (underlined) for cloning purposes: 5′ d-CGGAATTCGAGGAGYTGGAGSASATG and 5′ d-GCTCTAGATCAGAAYATSTCGTGHAGCTC. The polymerase chain reaction was performed with standard reagents (Perkin-Elmer, Emeryville, CA) and a DAMI cDNA template26 using a single start cycle (94°C for 120 seconds), 30 cycles of amplification (94°C for 30 seconds, 48°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 60 seconds) and a final extension cycle (72°C for 7 minutes). The amplified cDNA was ligated into the pCR vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and sequenced.

Recombinant Protein Production

The cDNA for PSP was ligated into the pMALc vector (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA) for expression as a fusion product with the maltose binding protein.27 A 1.3-kb 3′ cDNA fragment from the pBK-CMV-PSP phagemid was obtained by double digestion withEcoRI-Xho I and ligated into the pMalc vector (cut withEcoRI and Sal I). To ligate the remaining 5′ complete coding sequence of PSP into the vector, we synthesized a primer (d-AAAAAGATATCATGGCGCCGCCGGTGGCAG) that contained sequences corresponding to the translation start site of PSP and a synthetic EcoRV site (underlined). The antisense primer corresponded to the sequence of PSP beginning at nucleotide 1070. The two primers were used with a PSP cDNA template in a polymerase chain reaction under conditions outlined above.26 The amplified cDNA was cloned into the pCR vector (Invitrogen), and the DNA sequence was confirmed. The 5′ fragment was digested with EcoRV and EcoRI and ligated into the pMalc vector containing the 3′ PSP coding sequence, after it had been predigested withStu I and EcoRI. Recombinant (r) PSP was induced in bacteria, purified as described,28 and used as an immunogen (see below). For functional studies, PSP was also expressed as a His-tagged protein in sf-9 cells by homologous recombination. The cDNA for PSP was cloned into the plasmid pBlueBacHis2A (Invitrogen) in two steps. A 5′ fragment obtained by digesting the pMalc-PSP plasmid with BamHI and EcoRI was ligated into the plasmid that had been digested with the same enzymes. The 3′ fragment was obtained by digestion of the pBK-CMV-PSP phagemid with EcoRI and Xho I, and this fragment was ligated into vector precut with EcoRI and Sal I. The 5′ end of the assembled PSP coding sequence was sequenced to verify that the reading frame was correct. The recombined rPSP virus was used to infect cells at a multiplicity of 5; protein expression appeared optimal at 96 hours. The rPSP was purified under nondenaturing conditions by affinity chromatography on Ni-agarose (Invitrogen) using alkaline conditions (20 mmol/L sodium phosphate, 500 mmol/L NaCl, pH 7.8) for binding and mildly acidic conditions for elution (same buffer, pH 6.0).

pGEX-KG plasmids containing rat syntaxin 4 or SNAP-25 were obtained from Richard Scheller (Stanford University, Stanford, CA).29 r-Syntaxin 4 and r-SNAP-25 were produced in bacteria and purified on glutathione sepharose (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) as recommended by the manufacturer. The r-syntaxin 4 and r-SNAP-25 (2 μg) were coupled to glutathione sepharose beads (10 μL slurry) for 1 hour at room temperature. After 3 cycles of washing with phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4), the beads were incubated overnight with 10 μL of human platelet lysate (1.1 × 1010cells/mL in 1% Triton X-100 [Sigma, St Louis, MO] with 10 μmol/L leupeptin [Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA], 1 mmol/L phenylmethylsulfonylfluoride [Sigma], and 100 U/mL aprotinin) at 4°C. The beads were washed three times in phosphate-buffered saline with 1% Triton X-100. After boiling in sample buffer, the samples were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) followed by immunoblotting with anti-PSP peptide antibody (as described below).

Antibody Production

Anti-activated platelet antibody.

Platelets were isolated from platelet-rich plasma (Massachusetts General Hospital Blood Bank, Boston, MA) by differential centrifugation and washing.30 The platelets were split into two groups, and one group was activated with thrombin (0.15 U/mL; Sigma), as we have described.23 Washed, activated, or resting platelets (7.4 × 1010 cells/mL) were biotinylated with 40 μg/mL NHS-LC-biotin [sulfosuccinimidyl 6-(biotinamido) hexanoate; Pierce, Rockford, IL] for 2 hours at room temperature. After centrifugation at 3,000g for 20 minutes, the supernatants were removed and the platelets were washed again. The platelets were solubilized by the addition of 1% (final) Triton X-100 (Sigma) containing 100 U/mL aprotinin and 10 μmol/L leupeptin (Sigma). After centrifugation at 13,200 rpm for 5 minutes in microfuge tubes, the supernatant was added to a streptavidin column (1 mL; Pierce). The column was washed with phosphate-buffered saline (until the A280 was less than 0.01), and the biotinylated proteins were eluted with 8 mol/L guanidine (pH 1.5). The fractions were neutralized and dialyzed against phosphate-buffered saline with 1% Triton X-100. A male New Zealand rabbit (Charles River, Wilmington, MA) was immunized four times at 6-week intervals with approximately 1 mg of biotinylated proteins. Before library screening, the antiplatelet antibody was absorbed against the resting biotinylated platelet protein on a streptavidin column, and against an Escherichia coli Y1090 lysate, as described.23

Other antibodies.

A peptide corresponding to residues 269-277 of PSP was synthesized and coupled to keyhole limpet hemocyanin as described.31 After obtaining preimmune serum, we immunized New Zealand white rabbits (subcutaneously) with 50 to 100 μg of purified rPSP or 0.75 to 1 mg of KLH-PSP(269-277) peptide conjugate every 3 to 4 weeks. Antisera against syntaxin 4 and SNAP-25 were obtained by immunizing a New Zealand white rabbit with 100 μg of recombinant protein subcutaneously every 3 to 4 weeks. Antibody was purified on affinity resin containing the relevant peptide or fusion protein coupled to CNBr-activated sepharose (Sigma), as we have described.32

Northern Analysis

The DAMI33 and CCRF22 cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD). The CHRF cell line34 was a gift from Michael Lieberman (University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH). Poly(A)-containing mRNA (5 μg) was isolated, size fractionated on formaldehyde/agarose gels, and blotted and hybridized with an [α-32P]dCTP-labeled, 0.6-kbHindIII fragment of PSP using protocols we have described.23 The blots were exposed in a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA).

Protein Phosphorylation Studies

Phosphorylation with purified PKC.

Affinity-purified anti-PSP peptide antibody (0.5 mg) was coupled to CNBr-activated agarose (1 mL) as we have described.32Washed human platelets were solubilized in 10 mmol/L Tris HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mmol/L NaCl with 1 mmol/L CaCl2, 0.5 mmol/L leupeptin, 100 U/mL aprotinin, and 1% Triton X-100 and then sonicated. After centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 30 minutes, the lysate (15 mL) was incubated with antibody agarose at room temperature for 3 hours. The column was washed with 10 mmol/L Tris HCl, 500 mmol/L NaCl (pH 7.4) containing 1% Triton X-100 (until the A280 was less than 0.02). A similar wash with 10 mmol/L Tris HCl and 150 mmol/L NaCl (pH 7.4) followed. Bound protein was eluted with 0.1 mol/L glycine (pH 2.9) in 1-mL volumes and neutralized with 3 mol/L Tris-HCl (pH 9.0). Protein fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, concentrated, and dialyzed into MOPS-Ca2+ buffer (20 mmol/L MOPS, 1 mmol/L CaCl2, pH 7.2). Purified platelet PSP or baculovirus expressed rPSP (2 μg/15 μL) were mixed in a total volume of 50 μL with 10 μL ATP (0.5 mmol/L [Pharmacia] spiked with [γ32P]ATP [1 μL, 3000 Ci/mmol; Dupont-NEN, Boston, MA]), PKC (25 ng; a purified mixture of α, β, and γ isoforms; Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY), and 10 μL lipid activator (0.1 mg/mL phosphatidyl/serine with 0.1 mg/mL diglyceride) in assay buffer (20 mmol/L MOPS, 1 mmol/L CaCl2, 1 mmol/L sodium orthovanadate, 1 mmol/L dithiothreitol, 1 mmol/L MgCl2, pH 7.2) and incubated for 20 to 40 minutes at 30°C. The stoichiometry of phosphorylation was determined by measuring the specific incorporation of 32P into PSP on SDS-PAGE gels subjected to phosphorimaging. In other experiments, we measured the effect of PKC-mediated phosphorylation of PSP on syntaxin 4 binding in a competitive binding assay. Wells of a microtiter plate were coated with rPSP (50 μL of 50 μg/mL purified baculovirus-expressed protein) for 60 minutes at room temperature. After washing, nonspecific binding sites were blocked with 1% albumin. Syntaxin 4 (5 μg/mL in 0.1% BSA, 50 μL) was mixed with 50 μL of various types of treated (see below) PSP (40 μg/mL) or no PSP, and 50 μL of the reaction was added to the PSP-coated wells in duplicate. To make the changes in the syntaxin 4 binding directly proportional to the potential effects of PSP phosphorylation on binding, the assay was calibrated such that under normal conditions nonphosphorylated PSP would inhibit approximately 50% of the binding of syntaxin 4. Three types of treated PSP were used: normal (unmodified PSP), PKC-phosphorylated PSP (as described above), and mock-phosphorylated PSP (PSP incubated with the phosphorylation reagents without PKC). After 60 minutes, the wells were rinsed and anti-syntaxin 4 antibody (1:500 dilution) was added for 1 additional hour. After another rinse, the bound anti-syntaxin 4 antibody was detected by incubating with 125I-protein A (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL) for 60 minutes, washing, and γ scintillation counting.

Phosphorylation in permeabilized platelets.

Phosphorylation was studied in platelets permeabilized to introduce [γ32P]ATP as described by Carlson et al35with buffers described by Knight and Scrutton.36 Platelets were obtained from citrated whole blood and washed in 140 mmol/L NaCl, 20 mmol/L HEPES (pH 7.1), and 1 mmol/L ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid as described.35 After the wash, the platelets were resuspended in medium 1 (20 mmol/L K-PIPES [piperazine N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid)], 150 mmol/L K-glutamate, 7 mmol/L Mg-diacetate, 5 mmol/L glucose, 5 mmol/L K EGTA [ethylene glycol-bis (β-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid], pH to 7.4) at 1.4 × 109 cells/mL (100 μL), as described.36 Then, Na2ATP (1 μL, 500 mmol/L), [γ32P]ATP (5 μL, 3,000 Ci/mmol), 0.4 mmol/L CaCl2 (to achieve a pCa of 7), and medium 1 (100 μL) was mixed with saponin (prewarmed at 30°C) to achieve a concentration of 20 μg/mL.36 Thrombin (0.15 U/mL final), prostaglandin E1 (10 μmol/L; Sigma), or phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA; 100 nmol/L; Sigma), with or without Ro-31-8220 (1 μmol/L 3-[1-3-(amidinothio)propyl-1H-indolyl-3-yl]-3-(1-methyl-1H-indolyl-3-yl)maleimide methane sulfonate; Calbiochem) was added to this platelet reaction mixture. After 1 to 10 minutes at 30°C, the reactions were stopped by the addition of lysis buffer containing 0.5% SDS, 5 mmol/L NaF, 50 mmol/L sodium phosphate, 10 mmol/L sodium vanadate, 2 mmol/L ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid, 1 mmol/L phenylmethyl sulfonyl fluoride, 1 mmol/L dithiothreitol, 0.2 mg/mL leupeptin, and 10 mg/mL aprotinin. The samples were boiled for 3 minutes and cooled on ice, diluted in 2 mL of radioimmunoprecipitation (RIPA) buffer (1.25% [wt/wt] NP-40, 1.25% [wt/vol] sodium deoxycholate, 12.5 mmol/L NaPO4, pH 7.2, 2 mmol/L ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid, 0.2 mmol/L sodium vanadate, 50 mmol/L sodium fluoride, 100 U/mL aprotinin), and centrifuged at 23,000 rpm for 10 minutes. The supernatant was then incubated with 50 μL of anti-PSP peptide antibody coupled to sepharose (see above) or a control antibody coupled to sepharose for 2 hours at room temperature. The sepharose was subjected to two cycles of centrifugation (13,000 rpm for 10 minutes) and washed with 2 mL of RIPA buffer. The sepharose beads were then mixed with sample buffer containing 5% B-mercaptoethanol,37 boiled for 5 minutes, analyzed by SDS-PAGE on 7.5% gels, and subjected to phosphorimaging.

Immunoblotting, Immunoprecipitation, and Binding Assays

Immunoblotting was performed as we have described23according to standard procedures. For immunoprecipitation studies, affinity-purified antibodies (10 μg) were incubated with protein A agarose (Sigma) for 1 hour at room temperature. After washing, the agarose bound antibody was mixed with cell lysates overnight at 4°C. After washing 3 times with Tris-buffered saline, the agarose beads were mixed with sample buffer and boiled. The eluted protein samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by immunoblotting. The SP-12 monoclonal antibody was used to detect SNAP-25 and the SP-10 antibody was used to detect VAMP (both antibodies from Serotec, Oxford, UK).38 Bound antibody was detected by an enhanced chemiluminescent method (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, UK).

The competitive binding of PSP and SNAP-25 to syntaxin 4 was studied in a solid-phase assay. Wells of a microtiter plate were coated with r-PSP (50 μL, 0.15 μg/mL) for 2 hours and blocked with 1% BSA. Various amounts of r-SNAP-25 (0 to 425 μg/mL, final concentration) were mixed with 125I-r-syntaxin 4 (∼100,000 cpm) and 50 μL was added to the wells in duplicate. After 1 hour, the wells were washed and the amount of bound 125I-r-syntaxin 4 was determined by γ scintillation counting. The percentage of binding inhibition was determined by computing the fractional binding of125I-r-syntaxin 4 to PSP in the presence of various amounts of r-SNAP-25, in comparison with the binding in the absence of an inhibitor, after correcting for nonspecific binding.

RESULTS

Structure of PSP

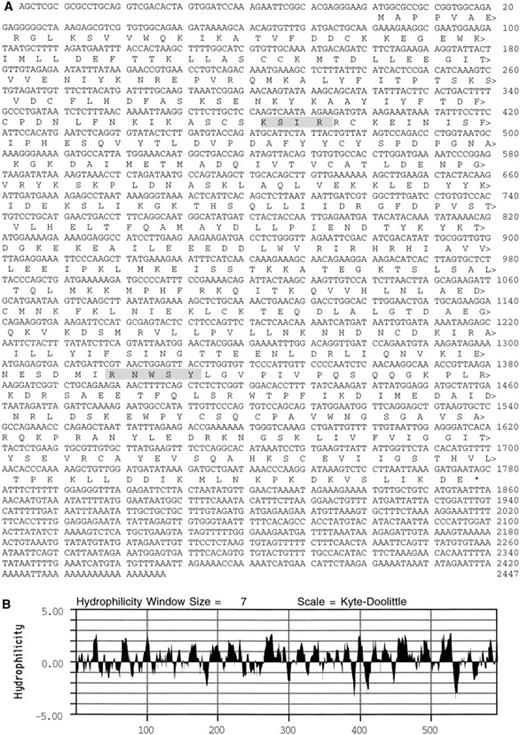

An antiplatelet antibody was used to identify a 2,552-kb cDNA in a library generated from a human leukemic cell line (CCRF) that expresses transcripts for many platelet proteins.22 The cDNA contains an ATG codon in a context suitable for initiation of translation.39 This ATG codon begins an open reading frame of 1776 nucleotides that codes for a 592 amino acid plateletSec1 protein (PSP; see homologues below), with a predicted molecular mass of 68 kD (Fig 1). After a termination codon, there is a 667-base 3′ untranslated sequence with two nuclear polyadenylation sequences40 and a poly(A) tail. An analysis of the deduced amino acid sequence predicted that PSP was largely hydrophilic41 and contained sequence motifs42 for PKC phosphorylation at residues 128-131 (KSIR) and for casein kinase II phosphorylation at PSP residues 440-444 (RNWSY).

Deduced amino acid sequence of PSP. (A) Shaded boxes highlight a potential PKC phosphorylation site at residues 128-131 and a casein kinase II phosphorylation site at residues 440-444. (B) Kyte-Doolittle41 hydrophilicity plot of the PSP sequence.

Deduced amino acid sequence of PSP. (A) Shaded boxes highlight a potential PKC phosphorylation site at residues 128-131 and a casein kinase II phosphorylation site at residues 440-444. (B) Kyte-Doolittle41 hydrophilicity plot of the PSP sequence.

Structural Homologues of PSP

The BLAST and BEAUTY programs were used to compare the nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of PSP with sequences in the NCBI database.43 At the nucleotide level, PSP showed strong homology to genes of the Sec1/unc-18 family that have been identified in yeast,44Drosophila,45C elegans, rats, and mice (Table 1). Their products are necessary for normal cellular secretion to occur in yeast,Drosophila, and mammalian neurons. In neurons, Munc-18 interacts with syntaxin 1 and is thought to be necessary for regulation of the interaction between syntaxin 1 and other components of the SNARE complex, SNAP-25 and VAMP. The Sec1 family of genes appears to have at least three members in mammals, represented by Munc-18-1 (rat), Munc-18b (mouse), and Munc-18c (mouse). PSP shows the greatest sequence identity with Munc-18c at the nucleotide (79%) and peptide (92%) levels; the PKC site is conserved in both molecules.46 At the peptide level, PSP has less sequence identity with Munc 18-1 (52%), Munc-18b (47%), and unc-18 (45%).

Sequence Similarities Among the unc-18 Proteins

| Protein (GenBank No.) . | unc-18* (S66716) . | Munc-18-1† (L26087) . | Munc 18b‡ (U19520) . | Munc-18c1-153 (U19521) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSP | 45% | 52% | 47% | 92% |

| unc-18 | 59% | 54% | 45% | |

| Munc-18-1 | 63% | 53% | ||

| Munc 18b | 47% |

| Protein (GenBank No.) . | unc-18* (S66716) . | Munc-18-1† (L26087) . | Munc 18b‡ (U19520) . | Munc-18c1-153 (U19521) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSP | 45% | 52% | 47% | 92% |

| unc-18 | 59% | 54% | 45% | |

| Munc-18-1 | 63% | 53% | ||

| Munc 18b | 47% |

Expression of PSP in Platelets

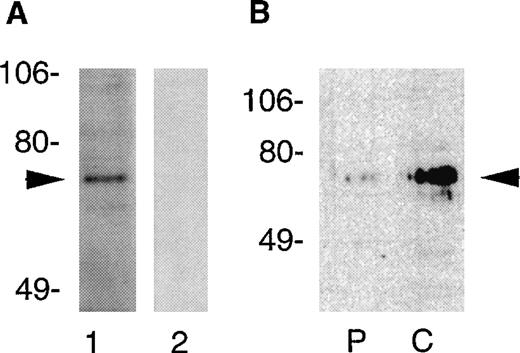

Because platelets contain only small amounts of partially degraded mRNA, we performed Northern blotting to confirm that PSP transcripts were expressed in megakaryocytic cell lines. The CHRF, DAMI, and CCRF cell lines all contained a single PSP transcript of approximately 2.7 kb (data not shown). To verify expression of PSP protein in platelets, we probed platelet lysates with antibodies directed against a peptide sequence in PSP spanning residues 269-277 (a region in which it bears no homology to other sequences of the Munc-18 family). By immunoblotting, these antibodies both identified an approximately 68-kD protein band in Triton X-100 platelet lysates that conforms to the predicted molecular mass of PSP (Fig 2A). This specific immunoreactive band was not seen in lysates probed with preimmune serum, and it could be specifically inhibited by the relevant immunogen. To determine the cellular location of PSP, we examined cell-cytosol and membrane-particulate fractions from platelets (Fig2B). These experiments indicated that PSP predominated in the cytosol, with small amounts also detected in the particulate or membrane fraction.

Detection of PSP in human platelets by immunoblotting. Platelets were lysed in 1% Triton X-100 and the lysate was subjected to SDS-PAGE (2 × 106 cells/lane). (A) Platelet proteins electroblotted to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes were probed with immune (lane 1, 1:500) or preimmune sera (lane 2, 1:500) generated against a peptide sequence of PSP spanning residues 269-277. Relative migration of protein standards (in kilodaltons) is indicated at left. The arrow indicates PSP. (B) Cellular distribution of PSP in platelets. The cellular fractions from human platelets were subjected to SDS-PAGE (2.1 × 106 cells/lane) and immunoblotted with anti-PSP sera. The particulate fractions are shown in lane P. The cytosolic fractions are shown in lane C.

Detection of PSP in human platelets by immunoblotting. Platelets were lysed in 1% Triton X-100 and the lysate was subjected to SDS-PAGE (2 × 106 cells/lane). (A) Platelet proteins electroblotted to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes were probed with immune (lane 1, 1:500) or preimmune sera (lane 2, 1:500) generated against a peptide sequence of PSP spanning residues 269-277. Relative migration of protein standards (in kilodaltons) is indicated at left. The arrow indicates PSP. (B) Cellular distribution of PSP in platelets. The cellular fractions from human platelets were subjected to SDS-PAGE (2.1 × 106 cells/lane) and immunoblotted with anti-PSP sera. The particulate fractions are shown in lane P. The cytosolic fractions are shown in lane C.

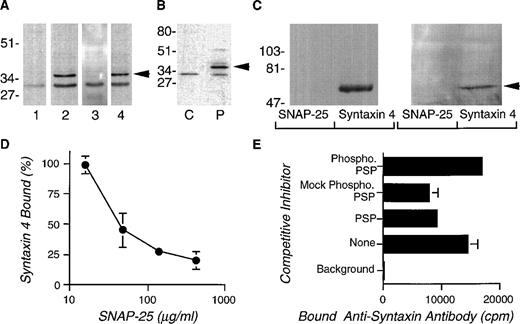

Phosphorylation of PSP

The presence of a conserved potential PKC site suggested that PSP may be phosphorylated by this secretion-linked kinase. Figure 3A shows that purified platelet PSP incorporated 32P when incubated in a phosphorylation reaction with purified PKC. Because the process of secretion is linked to cell stimulation by specific agonists, we investigated whether PSP was phosphorylated in vivo in permeabilized platelets activated by thrombin. Figure 3B shows that phosphorylated PSP was immunoprecipitated from platelets stimulated with thrombin for as little as 1 minute (first lane) and, with longer thrombin stimulation (10 minutes), the phosphorylation of PSP increased (second lane). No phosphorylation of PSP was detected in nonactivated cells (third lane), and a similar phosphoprotein was not seen in thrombin-treated cells stimulated for 10 minutes and immunoprecipitated with a control antibody (fourth lane). Because thrombin and other agonists are known to activate PKC in platelets, we explored whether the in vivo phosphorylation of PSP occurred through this kinase. Figure 3C shows that phosphorylated PSP was immunoprecipitated from platelets stimulated by PMA, a direct activator of PKC. This phosphorylation was blocked by the PKC inhibitor Ro-31-8220 in both PMA- and thrombin-treated cells.

Phosphorylation of PSP. (A) Phosphorylation of affinity-purified platelet PSP. Immunoaffinity purified PSP (2 μg) was phosphorylated in vitro with purified PKC (6.3 ng) and [γ32P]ATP for 20 minutes at 30°C and subjected to SDS-PAGE. Phosphoproteins were detected by phosphorimaging. Relative migration of molecular standards (in kilodaltons) is indicated at left. (B) Phosphorylation of PSP in thrombin-activated and unstimulated platelets. Washed human platelets (1.3 × 109 cells/100 μL) were permeabilized with saponin in the presence of [γ32P]ATP and incubated with or without thrombin (0.15 U/mL) at 30°C for 1 to 10 minutes. The cells were lysed, boiled for 3 minutes, and diluted in radioimmunoassay precipitation buffer. After immunoprecipitation with anti-PSP antibody or a control antibody, the phosphoproteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE on 7.5% gels and phosphorimaging. The presence or absence of thrombin, the precipitating antibody, and the time of incubation are shown for each lane. Arrow indicates PSP. (C) The role of PKC in phosphorylation of PSP. As described above, washed, saponin-permeabilized platelets were incubated with prostaglandin E1 (PGE1; 10 μmol/L), thrombin (0.15 U/mL), or PMA (100 nmol/L) in the presence or absence of the PKC inhibitor Ro-31-8220 (10 μmol/L) for 3 minutes at 30°C. The cells were lysed, boiled, and diluted in radioimmunoprecipitation buffer. After immunoprecipitation with the anti-PSP antibody, the pellet was subjected to SDS-PAGE and phosphorimaging.

Phosphorylation of PSP. (A) Phosphorylation of affinity-purified platelet PSP. Immunoaffinity purified PSP (2 μg) was phosphorylated in vitro with purified PKC (6.3 ng) and [γ32P]ATP for 20 minutes at 30°C and subjected to SDS-PAGE. Phosphoproteins were detected by phosphorimaging. Relative migration of molecular standards (in kilodaltons) is indicated at left. (B) Phosphorylation of PSP in thrombin-activated and unstimulated platelets. Washed human platelets (1.3 × 109 cells/100 μL) were permeabilized with saponin in the presence of [γ32P]ATP and incubated with or without thrombin (0.15 U/mL) at 30°C for 1 to 10 minutes. The cells were lysed, boiled for 3 minutes, and diluted in radioimmunoassay precipitation buffer. After immunoprecipitation with anti-PSP antibody or a control antibody, the phosphoproteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE on 7.5% gels and phosphorimaging. The presence or absence of thrombin, the precipitating antibody, and the time of incubation are shown for each lane. Arrow indicates PSP. (C) The role of PKC in phosphorylation of PSP. As described above, washed, saponin-permeabilized platelets were incubated with prostaglandin E1 (PGE1; 10 μmol/L), thrombin (0.15 U/mL), or PMA (100 nmol/L) in the presence or absence of the PKC inhibitor Ro-31-8220 (10 μmol/L) for 3 minutes at 30°C. The cells were lysed, boiled, and diluted in radioimmunoprecipitation buffer. After immunoprecipitation with the anti-PSP antibody, the pellet was subjected to SDS-PAGE and phosphorimaging.

Interactions Between PSP, SNAP-25, and Syntaxin 4

PSP is homologous to the Munc-18 proteins, which are believed to affect secretion through binding with specific members of the syntaxin family.19,47 We analyzed the DAMI megakaryocytic cell line for syntaxin transcripts by the polymerase chain reaction. Primers complementary to conserved sequences in syntaxins 1A, 1B, and 2-5 were used for amplification. Twelve clones were isolated and sequenced: 9 of 12 coded for syntaxin 4 and 3 of 12 coded for syntaxin 3. Syntaxin 4 is plasma membrane-bound and interacts in vitro with Munc-18c, which is the unc-18 protein most homologous to PSP.48Figure 4A shows that the anti-syntaxin 4 antibody (lane 2), but not the preimmune serum (lane 1), detected an approximately 35-kD band in immunoblots of platelet lysates. This immunoreactivity was inhibited by absorption with r-syntaxin 4 (lane 3), but not by a control protein (lane 4). Cell fractionation studies indicated that syntaxin 4, a membrane protein, was present, as expected, in the particulate fractions of platelets (Fig 4B) but not in the cytosol. Protein interaction studies showed that r-PSP interacted with r-syntaxin 4, but not with r-SNAP-25 (Fig 4C, left panel). More importantly, r-syntaxin 4 bound to PSP in Triton X-100–treated platelet lysates, whereas r-SNAP-25 protein did not (Fig 4C, right panel).

Syntaxin 4 in human platelets and its interaction with PSP. (A) Platelet lysates treated with Triton X-100 (1%) were subjected to SDS-PAGE on 15% gels and electroblotted to membranes. The blots were incubated with (lane 1) preimmune serum at 1:1,000, (lane 2) anti-syntaxin 4 antibody at 1:1,000, (lane 3) anti-syntaxin 4 antibody absorbed with recombinant glutathione-S transferase–syntaxin 4 at 1:1000, and (lane 4) anti-syntaxin 4 antibody absorbed with recombinant glutathione-S transferase at 1:1,000. Relative positions of molecular mass standards are indicated in kilodaltons. (B) Platelet cytosolic (C) or particulate (P) fractions (see above) were subjected to SDS-PAGE on 7.5% gels and immunoblotted with anti-syntaxin 4 antibody (1:1,000) as described above. The arrow indicates syntaxin-4 immunoreactivity. (C) Interaction of syntaxin 4 with PSP. r-PSP (left panel, 10 μg/300 μL) or human platelet lysate (right panel, 300 μL) was incubated with r-syntaxin or r-SNAP-25 coupled to glutathione sepharose beads overnight at 4°C. After a wash, protein bound to the beads was eluted with sample buffer and subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting with the anti-PSP peptide antibody (1:1,000). The arrow indicates the PSP-immunoreactive band. (D) Competition between r-SNAP-25 and r-PSP for binding to r-syntaxin 4. Various amounts of r-SNAP-25 (0 to 425 μg/mL, final) were mixed with125I-r-syntaxin 4 (∼100,000 cpm) and 50 μL was added to microtiter plate wells coated with r-PSP (50 μL, 0.15 μg/mL) in duplicate. After 1 hour, the wells were washed and the amount of bound125I-r-syntaxin 4 was determined by γ scintillation counting. The percentage of binding inhibition was determined by computing the fractional binding of 125I-r-syntaxin 4 to PSP in the presence of various amounts of r-SNAP-25, in comparison with the binding in the absence of an inhibitor, after correcting for nonspecific binding. (E) PKC-phosphorylation inhibits the binding of PSP to syntaxin 4. Microtiter plates coated with baculovirus expressed PSP or no PSP (background) were incubated with r-syntaxin 4 in the presence of equal amounts of various inhibitors: no PSP (none), PSP, mock-phosphorylated PSP, and PKC-phosphorylated PSP. To increase the sensitivity of the assay, the amount of PSP added as competitor was calibrated by preliminary assays to produce approximately 50% inhibition of r-syntaxin 4 binding. The amount of r-syntaxin 4 binding to the PSP-coated wells was determined by measuring the binding of anti-syntaxin 4 antibodies as detected by 125I-protein A.

Syntaxin 4 in human platelets and its interaction with PSP. (A) Platelet lysates treated with Triton X-100 (1%) were subjected to SDS-PAGE on 15% gels and electroblotted to membranes. The blots were incubated with (lane 1) preimmune serum at 1:1,000, (lane 2) anti-syntaxin 4 antibody at 1:1,000, (lane 3) anti-syntaxin 4 antibody absorbed with recombinant glutathione-S transferase–syntaxin 4 at 1:1000, and (lane 4) anti-syntaxin 4 antibody absorbed with recombinant glutathione-S transferase at 1:1,000. Relative positions of molecular mass standards are indicated in kilodaltons. (B) Platelet cytosolic (C) or particulate (P) fractions (see above) were subjected to SDS-PAGE on 7.5% gels and immunoblotted with anti-syntaxin 4 antibody (1:1,000) as described above. The arrow indicates syntaxin-4 immunoreactivity. (C) Interaction of syntaxin 4 with PSP. r-PSP (left panel, 10 μg/300 μL) or human platelet lysate (right panel, 300 μL) was incubated with r-syntaxin or r-SNAP-25 coupled to glutathione sepharose beads overnight at 4°C. After a wash, protein bound to the beads was eluted with sample buffer and subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting with the anti-PSP peptide antibody (1:1,000). The arrow indicates the PSP-immunoreactive band. (D) Competition between r-SNAP-25 and r-PSP for binding to r-syntaxin 4. Various amounts of r-SNAP-25 (0 to 425 μg/mL, final) were mixed with125I-r-syntaxin 4 (∼100,000 cpm) and 50 μL was added to microtiter plate wells coated with r-PSP (50 μL, 0.15 μg/mL) in duplicate. After 1 hour, the wells were washed and the amount of bound125I-r-syntaxin 4 was determined by γ scintillation counting. The percentage of binding inhibition was determined by computing the fractional binding of 125I-r-syntaxin 4 to PSP in the presence of various amounts of r-SNAP-25, in comparison with the binding in the absence of an inhibitor, after correcting for nonspecific binding. (E) PKC-phosphorylation inhibits the binding of PSP to syntaxin 4. Microtiter plates coated with baculovirus expressed PSP or no PSP (background) were incubated with r-syntaxin 4 in the presence of equal amounts of various inhibitors: no PSP (none), PSP, mock-phosphorylated PSP, and PKC-phosphorylated PSP. To increase the sensitivity of the assay, the amount of PSP added as competitor was calibrated by preliminary assays to produce approximately 50% inhibition of r-syntaxin 4 binding. The amount of r-syntaxin 4 binding to the PSP-coated wells was determined by measuring the binding of anti-syntaxin 4 antibodies as detected by 125I-protein A.

As noted earlier, the binding between the Munc-18a and syntaxin 1 prevents the binding of syntaxin 1 to SNAP-25 and VAMP, which are important for vesicle docking and fusion. Recent studies have shown that the murine PSP homologue (Munc-18c), through its binding to syntaxin 4, prevents VAMP from binding to syntaxin 4. We examined whether the binding of r-PSP to r-syntaxin 4 could compete with the binding of r-SNAP-25 to r-syntaxin 4. Figure 4D shows that increasing amounts of r-SNAP-25 effectively inhibited the binding of r-PSP to r-syntaxin 4.

As shown above, PSP is phosphorylated in activated platelets through a PKC-dependent mechanism. In previous studies, the phosphorylation of PSP homologue, Munc 18a, has been shown to inhibit syntaxin 1 binding. Consequently, we examined whether the phosphorylation of r-PSP altered its binding with syntaxin 4 in competitive binding experiments. Figure4E shows that PSP and mock-phosphorylated PSP (incubated with phosphorylation reagents but not PKC) competitively inhibited syntaxin 4 from binding to immobilized native PSP. However, PKC-phosphorylated PSP (0.87 ± 0.11 mol PO4/mol protein, N = 3) had no inhibitory effects, indicating that PKC phosphorylation interferes with the binding of r-PSP with syntaxin 4.

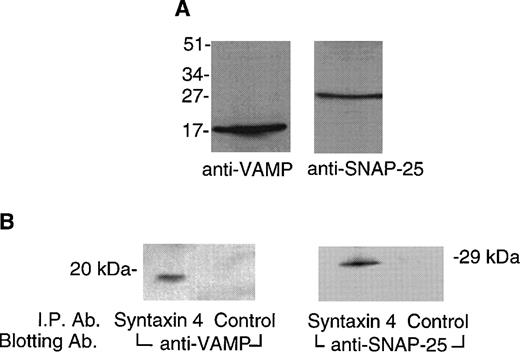

Interactions Between Vesicle Docking Proteins in Platelets

In neurons, syntaxin 1 interacts with VAMP and SNAP-25 to construct a trimolecular 7S core complex that docks vesicles with their target plasma membranes.18 We performed immunoblotting studies to determine whether these molecules were present in platelets. Figure 5A shows that VAMP was detected at a relative mass of approximately 16 kD with an anti-VAMP monoclonal antibody (SP-10)38 and that SNAP-25 was detected at an expected relative mass of approximately 25 kD with an anti-SNAP-25 monoclonal antibody (SP-12).38 Coimmunoprecipitation experiments were performed to determine whether syntaxin 4 interacted with these proteins in platelets. Figure 5B shows that antibody directed against syntaxin 4, but not a control antibody, coimmunoprecipitates both VAMP and SNAP-25 from solubilized platelet membranes, indicating that these two molecules are bound to syntaxin 4 in vivo.

VAMP and SNAP-25 are present in platelets and interact with syntaxin 4. (A) Detection of VAMP and SNAP-25 in platelet membranes. Platelet membranes (50 μg) solubilized in Triton X-100 (1%) were subjected to SDS-PAGE on 15% gels. Proteins were electroblotted to polyvinylidene membranes. The membranes were probed with monoclonal anti-VAMP antibody (SP10, 1:500 dilution) or monoclonal anti-SNAP-25 antibody (SP12, 1 μg/mL). Bound antibody was detected by an enhanced chemiluminescence method with a rabbit antimouse antibody coupled to peroxidase. Relative positions of molecular mass standards are indicated in kilodaltons. (B) VAMP and SNAP-25 coimmunoprecipitate with syntaxin 4. Triton X-100 (1%) solubilized platelet membranes (400 μL) were incubated overnight at 4°C with affinity-purified syntaxin 4 antibody or a control antibody. After washing, the bound proteins were eluted with sample buffer and subjected to SDS-PAGE and to immunoblotting with the anti-VAMP or anti-SNAP-25 antibodies as just described. Relative positions of molecular mass standards are indicated in kilodaltons.

VAMP and SNAP-25 are present in platelets and interact with syntaxin 4. (A) Detection of VAMP and SNAP-25 in platelet membranes. Platelet membranes (50 μg) solubilized in Triton X-100 (1%) were subjected to SDS-PAGE on 15% gels. Proteins were electroblotted to polyvinylidene membranes. The membranes were probed with monoclonal anti-VAMP antibody (SP10, 1:500 dilution) or monoclonal anti-SNAP-25 antibody (SP12, 1 μg/mL). Bound antibody was detected by an enhanced chemiluminescence method with a rabbit antimouse antibody coupled to peroxidase. Relative positions of molecular mass standards are indicated in kilodaltons. (B) VAMP and SNAP-25 coimmunoprecipitate with syntaxin 4. Triton X-100 (1%) solubilized platelet membranes (400 μL) were incubated overnight at 4°C with affinity-purified syntaxin 4 antibody or a control antibody. After washing, the bound proteins were eluted with sample buffer and subjected to SDS-PAGE and to immunoblotting with the anti-VAMP or anti-SNAP-25 antibodies as just described. Relative positions of molecular mass standards are indicated in kilodaltons.

DISCUSSION

Although many aspects of platelet secretion have been studied intensively, comparatively little is known of the molecular mediators of granule docking and fusion in these cells. We find that platelets contain a unique complement of interacting molecules whose homologues have been implicated in vesicle docking and fusion in other secretory cells. These studies were initially sparked by the discovery ofPSP in platelets,49 a previously uncharacterized human gene that is homologous to the Sec1, rop,unc-18, and Munc-18 gene family of secretory molecules. The deduced amino acid sequence of PSP predicts a hydrophilic protein with the potential for phosphorylation by PKC. Consistent with this prediction, PSP largely partitions, at the expected mass of 68 kD, to the cytosol of human platelets, with lesser amounts found in the membrane fraction. In vitro, PSP is phosphorylated by a purified mixture of isoenzymes of PKC (α, β, and γ), a kinase linked to platelet activation. In vivo, PSP is phosphorylated in platelets activated by thrombin. This in vivo phosphorylation proceeds through a PKC mechanism, because it is stimulated by PMA, an activator of the PKC system in platelets (which includes isoforms α, β, δ, η, andθ), and it is blocked by the PKC inhibitor Ro-31-8220.50 This PKC-mediated phosphorylation has functional importance, because it inhibits the binding between syntaxin 4 and PSP, an interaction that is postulated to regulate vesicle docking and secretion.18

Homologues of PSP—Sec1, rop, unc-18, and Munc-18—play a critical role in secretion. In yeast, Sec1 appears to be required for the terminal phase of vesicle secretion.44 In C elegans, unc-18 is necessary for the release of acetylcholine by neuronal cells.51 Overexpression of rop inDrosophila has an inhibitory effect on neurotransmitter release.45 There are three structurally distinct proteins of the mammalian unc-18 family (Munc-18-1 [or 18a], Munc-18b, and Munc-18c) that have different patterns of tissue expression and unique combinatorial interactions with different syntaxins.52-55Through their binding to the syntaxins, the Munc-18 proteins may regulate the formation of the macromolecular vesicle docking complex. For example, the tight binding of syntaxin 1 to Munc-18-1 prevents syntaxin 1 from binding to SNAP-25 and VAMP, thus inhibiting the formation of the 7S core complex that docks the vesicle at the target membrane in preparation for membrane fusion.18,47,52,53*

Our finding that platelets contain a full complement of interacting molecules important for vesicle docking and secretion argues that the SNARE hypothesis may be a useful paradigm for dissecting platelet degranulation. In support of this hypothesis, Lemons et al58 have reported that platelets are able to form 20S fusion complexes containing syntaxins 4 or 2, N-ethylmaleimide sensitive fusion protein, and soluble NSF attachment proteins.58 Additional evidence supporting the SNARE hypothesis is provided by ultrastructural studies that show platelet dense granules in close apposition to the plasma membrane in what appears to be a docking interaction.59 This granule-plasma membrane apposition or docking seems to be functionally important because it is highly correlated with the number of granules or serotonin released after Ca2+-induced exocytosis.59 Still, in platelets the biochemical relationships between 7S complex formation, vesicle docking, and cell activation remain unknown.

In studies of lysates of unstimulated platelets, we find that syntaxin 4 interacts with SNAP-25 and VAMP, suggesting that some degree of vesicle docking occurs in vivo. Although not directly examined in these experiments, it is likely that the degree of vesicle docking is modulated by the extent of platelet activation. PSP may play an important role in modulating this vesicle docking because of its capacity to interfere with the formation of the 7S complex. When platelet PSP binds syntaxin 4, this interaction excludes SNAP-25 binding (Fig 4D) and, analogously, the binding of PSP’s homologue Munc-18c to syntaxin 4 prevents VAMP binding.45 In turn, because PKC’s phosphorylation of PSP inhibits PSP-syntaxin 4 binding, this secretion-linked kinase may regulate PSP’s effects on vesicle docking. Studies in platelets, synaptosomes, motor nerve endings, and pancreatic cells have established that PKC plays a critical role in triggering vesicle secretion, although its mechanistic connections to the vesicle docking and fusion machinery remain poorly understood.15-17 The findings that PSP is phosphorylated through PKC after cellular stimulation by thrombin and that PKC-mediated phosphorylation perturbs PSP’s binding with syntaxin 4 provide a novel link between receptor-coupled cell activation, PKC-mediated intracellular signaling, and the molecules implicated in the regulation of vesicle docking and secretion.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors are grateful for the editorial assistance of Thomas McVarish. We thank Richard Scheller (Stanford University) for the plasmids for syntaxin 4 and SNAP-25 and Michael Lieberman (University of Cincinnati) for the CHRF cell line.

Indeed, the tight binding of PSP to syntaxin 4, a transmembrane protein, probably explains how PSP was detected and cloned by antibodies directed against platelet membrane proteins.

Supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant No. R01 HL57314-01 to G.L.R. and by a grant from Bristol-Myers Squibb to Harvard School of Public Health.

The nucleotide sequence reported in this paper has been submitted to the Genbank with accession no. AF032922.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to Guy L. Reed, MD, Cardiovascular Biology Laboratory, Harvard School of Public Health, 677 Huntington Ave, Boston, MA 02115; e-mail: reed@cvlab.harvard.edu.

![Fig. 3. Phosphorylation of PSP. (A) Phosphorylation of affinity-purified platelet PSP. Immunoaffinity purified PSP (2 μg) was phosphorylated in vitro with purified PKC (6.3 ng) and [γ32P]ATP for 20 minutes at 30°C and subjected to SDS-PAGE. Phosphoproteins were detected by phosphorimaging. Relative migration of molecular standards (in kilodaltons) is indicated at left. (B) Phosphorylation of PSP in thrombin-activated and unstimulated platelets. Washed human platelets (1.3 × 109 cells/100 μL) were permeabilized with saponin in the presence of [γ32P]ATP and incubated with or without thrombin (0.15 U/mL) at 30°C for 1 to 10 minutes. The cells were lysed, boiled for 3 minutes, and diluted in radioimmunoassay precipitation buffer. After immunoprecipitation with anti-PSP antibody or a control antibody, the phosphoproteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE on 7.5% gels and phosphorimaging. The presence or absence of thrombin, the precipitating antibody, and the time of incubation are shown for each lane. Arrow indicates PSP. (C) The role of PKC in phosphorylation of PSP. As described above, washed, saponin-permeabilized platelets were incubated with prostaglandin E1 (PGE1; 10 μmol/L), thrombin (0.15 U/mL), or PMA (100 nmol/L) in the presence or absence of the PKC inhibitor Ro-31-8220 (10 μmol/L) for 3 minutes at 30°C. The cells were lysed, boiled, and diluted in radioimmunoprecipitation buffer. After immunoprecipitation with the anti-PSP antibody, the pellet was subjected to SDS-PAGE and phosphorimaging.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/93/8/10.1182_blood.v93.8.2617/5/m_blod40819003w.jpeg?Expires=1767696038&Signature=Vn~nE5I6Dj2s~YBOn0e-oTRqJbNYgDtY762KpA4Ih0NEWMudBaVNskDykSiKaiM8lL~P6kRlpcHnxH~-fbnj0CdrJtbSbJeznhs-2MxRbtAvdsUpvzGbigkZeyIpRJIJ4bGnYxhm5LfNUbZ8NLoHPZ07u47osrxK2k96o2Mvgd7VP5ybR9gliSp0G0KvEoxUYUcJG3ej2~Lhf93HT-Gl~N77-CT3NqzAtQrRckdqSN5tohZZUa-iowSErDdYNvf3va51NafiL9LYRY6579wbu-FRIOwcWBWDlQLhUaS8Rlk6ZpZ2SWoSUvbggsDLGE~taKtUJKw2fNhGcvTI-LySag__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal