Abstract

Hodgkin’s disease (HD) is a lymphoid malignancy characterized by infrequent malignant cells surrounded by abundant inflammatory cells. In this study, we examined the potential contribution of chemokines to inflammatory cell recruitment in different subtypes of HD. Chemokines are small proteins that are active as chemoattractants and regulators of cell activation. We found that HD tissues generally express higher levels of interferon-γ–inducible protein-10 (IP-10), Mig, RANTES, macrophage inflammatory protein-1 (MIP-1), and eotaxin, but not macrophage-derived chemotactic factor (MDC), than tissues from lymphoid hyperplasia (LH). Within HD subtypes, expression of IP-10 and Mig was highest in the mixed cellularity (MC) subtype, whereas expression of eotaxin and MDC was highest in the nodular sclerosis (NS) subtype. A significant direct correlation was detected between evidence of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection in the neoplastic cells and levels of expression of IP-10, RANTES, and MIP-1. Levels of eotaxin expression correlated directly with the extent of tissue eosinophilia. By immunohistochemistry, IP-10, Mig, and eotaxin proteins localized in the malignant Reed-Sternberg (RS) cells and their variants, and to some surrounding inflammatory cells. Eotaxin was also detected in fibroblasts and smooth muscle cells of vessels. These results provide evidence of high level chemokine expression in HD tissues and suggest that chemokines may play an important role in the recruitment of inflammatory cell infiltrates into tissues involved by HD.

HODGKIN’S DISEASE (HD) is a lymphoid malignancy characterized by infrequent malignant Reed-Sternberg (RS) and Hodgkin’s cells within an environment of nonmalignant cells, including T cells, macrophages, fibroblasts, plasma cells, eosinophils, and neutrophils. The occurrence of relatively rare neoplastic cells within a context of reactive cells has suggested that a prominent local inflammatory response to the RS and Hodgkin’s cells is a key feature of this malignancy. The intense inflammation could reflect an insufficient and/or ineffective antitumor response that may itself contribute to the disease.

A number of studies have documented that HD is a neoplasia associated with abnormal cytokine production.1-3 Excess production of the inhibitory cytokine, interleukin (IL)-10, may contribute to reduced T-cell immunity, and abnormally high levels of IL-6, IL-1, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α may account for some of the constitutional symptoms that are commonly associated with HD.1,4 Other aspects of HD, including peripheral blood eosinophilia, plasmacytosis, and thrombocytosis could also be contributed by abnormally high cytokine levels of IL-3 and IL-5, IL-6 and IL-11, respectively.4 However, systemic cytokine imbalances are unlikely to explain the characteristic cellular infiltrates that surround the malignant cells. Rather, the nature of cellular infiltrates in HD tissues could be explained on the basis of certain chemokines being locally produced promoting selective cell migration.

Recent studies in an athymic mouse model have described a host response to Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-immortalized cells and identified two mediators of this response as the CXC chemokines IP-10 and Mig.5-7 Increased production of IP-10 and Mig was also identified in the EBV-positive lymphomatous tissues representative of lymphomatoid granulomatosis and nasal or nasal-type T/natural killer (NK) cell lymphoma.8 Chemokines are members of a family of small proteins that are active as chemoattractants and cell activators.9 Some members of this family have received considerable attention because they display selectivity of cell targets and receptors. This selectivity has suggested the possibility that the cellular composition of inflammatory responses may, in part, be a function of the chemokines being produced at a site. Except for preliminary results on expression of IL-8, a neutrophil chemoattractant and activating factor, and the related monocyte chemotactic peptide-1 (MCP-1) that attracts and activates monocytes, there is limited information on the involvement of other chemokines in the pathogenesis of the cellular infiltrates that characterize HD and its histologic subtypes.1 3

In this study, we examined the potential contribution of chemokines to the inflammatory response in HD tissues and the various disease subtypes. In particular, we have focused on the CXC chemokines, IP-10 and Mig, that are chemoattractant for T and NK cells and their relationship to positivity with EBV, and the CC chemokine eotaxin that is a chemoattractant for eosinophils and its relationship to tissue eosinophilia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Case selection.

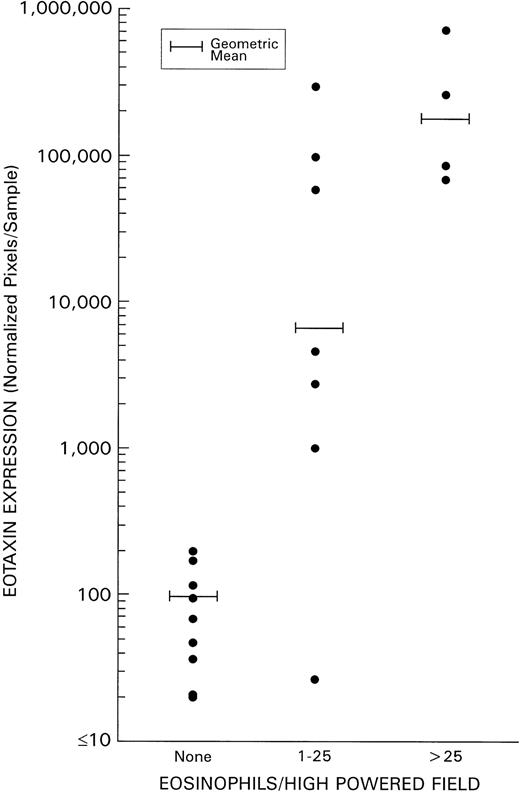

Lymph node biopsies were retrieved from the consultation files of one of us (E.S.J.) in the Hematopathology Section, Laboratory of Pathology, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health (NIH). Cases included: HD, 20 cases, further subclassified as mixed cellularity (MC), 6 cases; nodular sclerosis (NS), 9 cases; nodular lymphocyte predominant (NLP), 5 cases; and 6 control cases of reactive lymphoid hyperplasia (RLH). All patients were human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) negative. HD cases were classified according to the Revised European American Lymphoma (REAL) classification.10 By immunohistochemistry, the neoplastic cells (RS, Hodgkin’s or “popcorn cells”) stained positively with LeuM1 (CD15) and BerH2 (CD30) in the MC and NS subtypes and positively with L26 (CD20) in the NLP subtype. The extent of tissue eosinophilia was determined by two of us (J.T.F. and E.S.J.) by counting the number of eosinophils present in at least 20 separate high powered fields using an ocular grid eyepiece and calculating the mean number of eosinophils per sample. Within a given biopsy section, we selected areas involved by HD containing the greatest proportion of eosinophils. Samples were classified as having 0 eosinophils/high powered field, 1 to 25 eosinophils/high powered field, or >25 eosinophils/high powered field.

EBV in situ hybridization.

In situ hybridization used an EBV probe specific for EBV-encoded small RNAs (EBER), as described previously11 using an automated system (Ventana Medical System, Inc, Tuscon, AZ).

Reverse transcriptase-mediated polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR).

RNA extraction from paraffin-embedded tissue was performed as previously described.8 Briefly, 6 to 10 20-μm paraffin sections were deparaffinized three times in xylene (with heating at 55°C for 10 minutes), twice in 100% ethanol, and twice in 70% ethanol. Sections were suspended in 1 mL extraction buffer (10 mmol/L NaCl, 50 mmol/L Tris-HCL, pH 7.4, 20 mmol/L EDTA, 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS]) at 55°C overnight with 500 μg/μL proteinase K. After addition of 1 mL of RNA Trizol (GIBCO/BRL, Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD) and 200 μL of chloroform, followed by centrifugation, the aqueous phase was combined with an equal volume of isopropanol. The precipitated pellet was washed with 70% ethanol and resuspended in diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated water. RT-PCR applied to highly degraded RNA obtained from paraffin-embedded tissues was performed as previously described.8 Briefly, RNA samples were DNAse treated (GIBCO/BRL, Life Technologies), then subjected to an initial assay for amplifiable contaminating genomic DNA using primers specific for glyceradehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (G3PDH) mRNA. Positive samples were retreated with DNase, negative samples (2 to 5 μg) were reverse transcribed using an RNase H-RT (Superscript; GIBCO/BRL, Life Technologies). The resultant cDNA (25 to 100 ng) was amplified as previously described.8 The amount of cDNA used for each amplification reaction was based for each sample on the results of PCR for G3PDH showing equivalent amounts of product amplified from all samples. The selection of G3PDH was based on the observation that G3PDH mRNA is not known to vary in human tisses depending on disease status. Primers, listed in Table 1, were designed for amplification of short amplicons (80 to 130 bp) from highly degraded RNA and spanned at least one splice junction. Genomic DNA could be distinguished from mRNA or cDNA. Amplifications were performed in a thermocycler (Stratagene Robocycler, La Jolla, CA) adding 1.25 U Taq polymerase (GIBCO/BRL) after heating at 94°C for 3 minutes (“Hot Start”); followed by a predetermined number of amplification cycles (94°C, 45 seconds; primer annealing temperature as specified in Table 1 and extension at 72°C); and maintained at 4°C until analysis. The number of amplification cycles was determined experimentally for each primer pair to fit the linear part of the sigmoid curve reflecting the relationship between the number of amplification cycles and amount of PCR product. PCR products were detected by quantitating incorporated32P-labeled nucleotides [α-32P]deoxycytidine triphosphate (dCTP) (specific activity of ≈ 3,000 Ci/mmol) obtained from Amersham, Inc (Arlington Heights, IL). The entire amplification reaction (50 μL) was analyzed by electrophoresis on 8% acrylamide (Long Ranger; AT Biochem, Malvern, PA) Tris-borate EDTA gels (polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis [PAGE]), followed by autoradiography and quantitation by phosphorimage analysis using ImageQuantTM v3.3 software (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA). Band integrations were obtained as the sum of values for all pixels after subtraction of background (areas around each sample). Integrated values for each sample were then normalized for the results of parallel RT-PCR amplification for G3PDH expressed as pixels. The results of RT-PCR analysis are presented as absolute numbers of normalized arbitrary units (pixels)/sample. The ability of the RT-PCR assay to detect quantitative differences in mRNA for each gene product was assessed in experiments where the input cDNA derived from RNA extracted from paraffin-embedded tissues was first serially diluted (100 ng to 1 ng) and then subjected to PCR amplification. Using paraffin-embedded tissues positive for a given gene product along with appropriate negative controls, we verified that the intensity of the PCR product correlated with the dilution of input cDNA in the range used for PCR (25 to 100 ng). Variability of results from different experiments was minimized by use of standard control RNA preparations in parallel PCR. Experiments were considered evaluable only if standard control PCR results were within 15% of the mean.

PCR Primers and Conditions

| PCR Product . | Genbank Accession . | Primer Sequence (5′; 3′) . | Cycle No. . | Anneal Temperature (°C) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mig | X72755S60728 | TTCCTCTTGGGCATCATCTTGCTG; GGTCTTTCAAGGATTGTAGGTGGA | 35 | 59 |

| IP-10 | X02530M17752 | GGAACCTCCAGTCTCAGCACC; GCGTACGGTTCTAGAGAGAGGTAC | 35 | 59 |

| IFN-γ | V00536 AO4665 | GGACCCATATGTAAAAGAAGCAGA; TGTCACTCTCCTCTTTCCAATTCT | 35 | 57 |

| TNF-α | M10988 | TCAGCTTGAGGGTTTGCTACAA; TCTGGCCCAGGCAGTCAGATC | 35 | 59 |

| RANTES | M21121 | GGCACGCCTCGCTGTCATCCTCA; CTTGATGTGGGCACGGGGCAGTG | 35 | 65 |

| MIP-1α | M25315 | CTCTGCACCATGGCTCTCTGCAAC; TGTGGAATCTGCCGGGAGGTGTAG | 35 | 62 |

| Eotaxin | D49372 | ACATGAAGGTCTCCGCAGCACTTC; TTGGCCAGGTTAAAGCAGCAGGTG | 35 | 61 |

| MDC | U83171 | ATGGCTCGCCTACAGACTGCACTC; CACGGCAGCAGACGCTGTCTTCCA | 35 | 62 |

| G3PDH | M33197M32599 | GCCACATCGCTAAGACACCATGGG; CCTGGTGACCAGGCGCCCAAT | 35 | 59 |

| PCR Product . | Genbank Accession . | Primer Sequence (5′; 3′) . | Cycle No. . | Anneal Temperature (°C) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mig | X72755S60728 | TTCCTCTTGGGCATCATCTTGCTG; GGTCTTTCAAGGATTGTAGGTGGA | 35 | 59 |

| IP-10 | X02530M17752 | GGAACCTCCAGTCTCAGCACC; GCGTACGGTTCTAGAGAGAGGTAC | 35 | 59 |

| IFN-γ | V00536 AO4665 | GGACCCATATGTAAAAGAAGCAGA; TGTCACTCTCCTCTTTCCAATTCT | 35 | 57 |

| TNF-α | M10988 | TCAGCTTGAGGGTTTGCTACAA; TCTGGCCCAGGCAGTCAGATC | 35 | 59 |

| RANTES | M21121 | GGCACGCCTCGCTGTCATCCTCA; CTTGATGTGGGCACGGGGCAGTG | 35 | 65 |

| MIP-1α | M25315 | CTCTGCACCATGGCTCTCTGCAAC; TGTGGAATCTGCCGGGAGGTGTAG | 35 | 62 |

| Eotaxin | D49372 | ACATGAAGGTCTCCGCAGCACTTC; TTGGCCAGGTTAAAGCAGCAGGTG | 35 | 61 |

| MDC | U83171 | ATGGCTCGCCTACAGACTGCACTC; CACGGCAGCAGACGCTGTCTTCCA | 35 | 62 |

| G3PDH | M33197M32599 | GCCACATCGCTAAGACACCATGGG; CCTGGTGACCAGGCGCCCAAT | 35 | 59 |

Abbreviations: Mig, monokine induced by interferon-γ; IP-10, interferon-γ–inducible protein-10; IFN-γ, interferon-γ; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; RANTES, regulated uponactivation, normal T expressed andsecreted; MIP1-α, macrophage inflammatory protein 1-α; MDC, macrophage-derived chemotactic factor; G3PDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

IP-10, Mig, and eotaxin immunohistochemistry.

Reactions were performed as previously described.8 Briefly, to enhance chemokine detection, tissue sections were first treated with a Target Retrieval Solution (DAKO Corp, Carpenteria, CA) in a microwave pressure cooker (Nordic Ware, Minneapolis, MN) at maximum power (800 W) for 8 minutes, then washed in 0.05 mol/L Tris-HCL saline (TBS, pH 7.6 containing 5% fetal calf serum [FCS]; GIBCO Laboratories, Grand Island, NY) for 30 minutes. The slides were incubated with primary antibodies including rabbit antihuman IP-10 purified antibody (1:1,000 dilution, Peprotech Inc, Rocky Hill, NJ), or rabbit antihuman Mig antiserum (1:5,000 dilution, a generous gift from Dr Joshua Farber, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases [NIAID], NIH) overnight at room temperature, or rabbit antihuman eotaxin antiserum (1:40 dilution, Peprotech Inc) for 30 minutes at room temperature. Antibody dilutions were made with TBS containing 10% FCS and 0.1% (wt/vol) NaN3. Bound antibodies were detected with a biotin-conjugated universal secondary antibody formulation, which recognizes rabbit immunoglobulins (Ventana Medical Systems). After addition of an avidin-horseradish peroxidase conjugate, the enzyme complex was visualized with 3,3’-diaminobenzdine tetrachloride (DAB) and copper sulfate.

Statistical analysis.

Geometric means, standard errors of the mean (SEM) used conventional formulas. The significance of group differences was calculated by the Wilcoxon rank sums test. The significance of nonparametric measures of association was calculated by the Kendall Tau test.

RESULTS

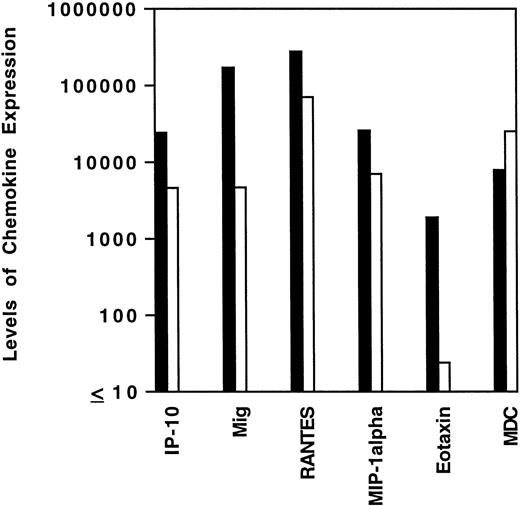

To assess cytokine and chemokine gene expression in HD tissues, total RNA was extracted from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues (total number, 20) involved by HD of the MC (6 cases), NS (9 cases), and NLP (5 cases) subtypes. In situ hybridization for the EBV-encoded small RNAs (EBERs) showed neoplastic cells latently infected with EBV in 7 of 19 cases (no tissue remained in the paraffin block from one case). Selected patient and tissue information is listed in Table 2. Control RNA was extracted from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues representative of reactive lymphoid hyperplasia (RLH, 6 cases). All control cases of RLH tested EBV-negative by EBER-1 in situ hybridization. Using a semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis of tissues involved by HD, we found the PCR products for interferon (IFN)-γ, TNF-α, and for the chemokines Mig, IP-10, RANTES, MIP-1α, MDC, and eotaxin to be amplified at variable levels (representative results shown in Fig 1). When compared with RLH tissues (Fig 2), levels of expression of IP-10, Mig, RANTES, MIP-1α, and eotaxin were significantly higher in HD tissues (IP-10, P = .04; Mig,P = .01; RANTES, P = .03; MIP-1α, P = .04; eotaxin, P = .04). In contrast, MDC expression levels were similar in the two groups (P = .73).

HD Patients, Tissue EBV Status, and Extent of Eosinophilia

| Patient . | Age/Sex . | Site . | EBV* in Neoplastic Cells . | Extent of Eosinophilia† . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MC | ||||

| 1 | 69/F | LN | + | 1 |

| 2 | 46/M | Mediastinum | + | 0 |

| 3 | 45/M | LN, R scalene | + | 1 |

| 4 | 58/F | LN, retroperit | + | 0 |

| 5 | 76/F | LN, L cervical | + | 1 |

| 6 | 84/F | LN, cervical | − | 0 |

| NS | ||||

| 1 | 45/F | R neck | + | 1 |

| 2 | 78/M | Pelvic mass | + | 2 |

| 3 | 36/F | LN, R cervical | − | 1 |

| 4 | 27/F | LN, L cervical | − | 1 |

| 5 | 28/F | Mediastinum | − | 2 |

| 6 | 54/F | LN, R inguinal | − | 0 |

| 7 | 45/M | Pericardium | − | 1 |

| 8 | 38/M | Mediastinum | − | 2 |

| 9 | 27/M | LN, R cervical | NT | 2 |

| NLP | ||||

| 1 | 23/M | LN, L inguinal | − | 0 |

| 2 | 9/M | L neck mass | − | 0 |

| 3 | 57/M | LN, L neck | − | 0 |

| 4 | 42/F | LN, L neck | − | 0 |

| 5 | 49/F | LN, R inguinal | − | 0 |

| Lymphoid Hyperplasia | ||||

| 1 | 59/F | LN, neck | − | 0 |

| 2 | 38/F | LN, inguinal | − | 0 |

| 3 | 12/M | LN, neck | − | 0 |

| 4 | 57/F | LN, cervical | − | 0 |

| 5 | 40/M | LN, cervical | − | 0 |

| 6 | 16/M | LN, cervical | − | 1 |

| Patient . | Age/Sex . | Site . | EBV* in Neoplastic Cells . | Extent of Eosinophilia† . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MC | ||||

| 1 | 69/F | LN | + | 1 |

| 2 | 46/M | Mediastinum | + | 0 |

| 3 | 45/M | LN, R scalene | + | 1 |

| 4 | 58/F | LN, retroperit | + | 0 |

| 5 | 76/F | LN, L cervical | + | 1 |

| 6 | 84/F | LN, cervical | − | 0 |

| NS | ||||

| 1 | 45/F | R neck | + | 1 |

| 2 | 78/M | Pelvic mass | + | 2 |

| 3 | 36/F | LN, R cervical | − | 1 |

| 4 | 27/F | LN, L cervical | − | 1 |

| 5 | 28/F | Mediastinum | − | 2 |

| 6 | 54/F | LN, R inguinal | − | 0 |

| 7 | 45/M | Pericardium | − | 1 |

| 8 | 38/M | Mediastinum | − | 2 |

| 9 | 27/M | LN, R cervical | NT | 2 |

| NLP | ||||

| 1 | 23/M | LN, L inguinal | − | 0 |

| 2 | 9/M | L neck mass | − | 0 |

| 3 | 57/M | LN, L neck | − | 0 |

| 4 | 42/F | LN, L neck | − | 0 |

| 5 | 49/F | LN, R inguinal | − | 0 |

| Lymphoid Hyperplasia | ||||

| 1 | 59/F | LN, neck | − | 0 |

| 2 | 38/F | LN, inguinal | − | 0 |

| 3 | 12/M | LN, neck | − | 0 |

| 4 | 57/F | LN, cervical | − | 0 |

| 5 | 40/M | LN, cervical | − | 0 |

| 6 | 16/M | LN, cervical | − | 1 |

Abbreviations: NT, no tissue available; retroperit, retroperitoneal.

EBER1 expression was assessed by in situ hybridization.

Grade of tissue eosinophilia was determined; 0 = no eosinophils/high powered field; 1 = 1-25 eosinophils/high powered field; 2 = >25 eosinophils/high powered field).

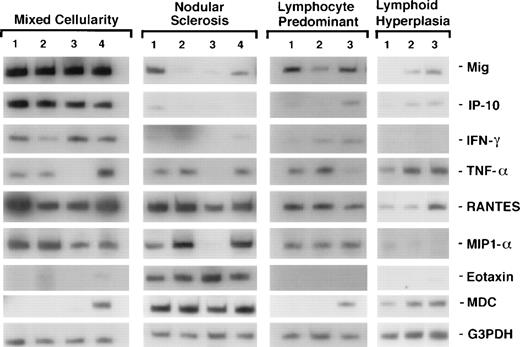

Patterns of cytokine and chemokine mRNA expression in HD tissues shown by RT-PCR analysis. Total cellular RNA, extracted from paraffin-embedded tissues representative of HD MC, NS, NLP, and of lymphoid hyperplasia, was subjected to RT-PCR analysis using appropriately designed primers.

Patterns of cytokine and chemokine mRNA expression in HD tissues shown by RT-PCR analysis. Total cellular RNA, extracted from paraffin-embedded tissues representative of HD MC, NS, NLP, and of lymphoid hyperplasia, was subjected to RT-PCR analysis using appropriately designed primers.

Levels of chemokine mRNA expression in HD tissues and lymphoid hyperplasia. Total cellular RNA, extracted from paraffin-embedded tissues diagnosed with HD (▪) and lymphoid hyperplasia (□) was subjected to semiquantitative RT-PCR. After normalization to a standard RNA preparation and to G3PDH, the results of phosphorimage analysis are shown and plotted logarithmically as the geometric means (x/÷ SEM) of normalized arbitrary units (pixels)/group for each respective chemokine. SEMs were too small to be distinguished from the mean.

Levels of chemokine mRNA expression in HD tissues and lymphoid hyperplasia. Total cellular RNA, extracted from paraffin-embedded tissues diagnosed with HD (▪) and lymphoid hyperplasia (□) was subjected to semiquantitative RT-PCR. After normalization to a standard RNA preparation and to G3PDH, the results of phosphorimage analysis are shown and plotted logarithmically as the geometric means (x/÷ SEM) of normalized arbitrary units (pixels)/group for each respective chemokine. SEMs were too small to be distinguished from the mean.

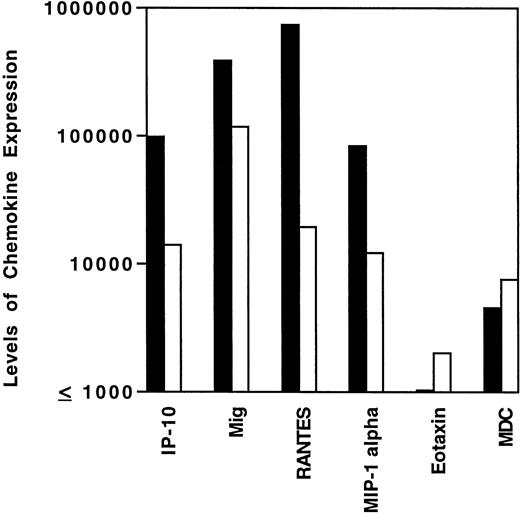

The variability in levels of cytokine and chemokine gene expression in HD tissues prompted us to examine whether the presence of EBV in the malignant cells and/or the histological subtype might correlate with certain patterns of cytokine and/or chemokine gene expression. Previous experiments had demonstrated that, in athymic mice, EBV-infected human lymphoblastoid cells elicit a characteristic cytokine and chemokine response, including elevated expression of murine IFN-γ, IL-6, TNF-α, IP-10, and Mig.6 7 By contrast, EBV-negative Burkitt cells generally do not elicit this response. We found mean tissue levels of IP-10, Mig, RANTES, and MIP-1α expression to be higher in EBV-positive than in EBV-negative HD tissues (Fig 3), and this difference was significant for IP-10 (P = .05, Wilcoxon rank sums test), RANTES (P = .005), and MIP-1α, (P = .02) and approached significance for Mig (P = .1). By contrast, expression levels of MDC and eotaxin were similar (P= .97 in both cases) in EBV-positive and negative HD tissues (Fig3). Thus, the presence of EBV in HD tissues is generally associated with higher level expression of certain chemokines, including IP-10, Mig, RANTES, and MIP-1α.

Levels of chemokine mRNA expression in EBV-positive (▪) and EBV-negative (□) HD tissues. Total cellular RNA, extracted from paraffin-embedded tissues diagnosed with MC, NS, or NLP HD was subjected to semiquantitative RT-PCR. After normalization to a standard RNA preparation and to G3PDH, the results of phosphorimage analysis are shown and plotted logarithmically as the geometric means (x/÷ SEM) of normalized arbitrary units (pixels)/group for each respective chemokine. SEMs were too small to be distinguished from the mean.

Levels of chemokine mRNA expression in EBV-positive (▪) and EBV-negative (□) HD tissues. Total cellular RNA, extracted from paraffin-embedded tissues diagnosed with MC, NS, or NLP HD was subjected to semiquantitative RT-PCR. After normalization to a standard RNA preparation and to G3PDH, the results of phosphorimage analysis are shown and plotted logarithmically as the geometric means (x/÷ SEM) of normalized arbitrary units (pixels)/group for each respective chemokine. SEMs were too small to be distinguished from the mean.

Because EBV infection is most frequent in the MC disease subtype (60% to 70% positive) of HD as compared with the NS (approximately 40% positive) and NLP (usually EBV-negative) subtypes,10 12this group might also display increased expression of those EBV-associated cytokines and chemokines compared with the other disease subtypes. The seven EBV-positive HD cases studied here were classified as belonging to the MC subtype in five cases and to the NS subtype in two cases. When analyzed by subtype (Table3), the MC group expressed geometric mean levels of IP-10, Mig, and MIP-1α that were higher compared with the other subgroups, and this difference reached significance for IP-10 (P = .01) and Mig (P = .04). Expression of RANTES, which correlated with the highest degree of significance with EBV-positive status, was most abundant in the NS subtype, which was largely due to the high levels of RANTES expression by the two EBV-positive cases in this group.

Levels of Chemokine mRNA Expression in Lymphoid Hyperplasia and HD Tissues

| Chemokines . | RLH . | Hodgkin’s MC . | Hodgkin’s NS . | Hodgkin’s NLP . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IP-10 | 4559 | 174159 | 7888 | 17074 |

| (x/÷1.6) | (x/÷1.17) | (x/÷2.47) | (x/÷1.82) | |

| Mig | 4648 | 612873 | 75030 | 168569 |

| (x/÷5.8) | (x/÷1.13) | (x/÷1.82) | (x/÷1.63) | |

| MIP-1α | 6989 | 73063 | 17665 | 14904 |

| (x/÷1.8) | (x/÷1.36) | (x/÷2.41) | (x/÷1.65) | |

| RANTES | 70104 | 342983 | 567879 | 92309 |

| (x/÷1.6) | (x/÷1.77) | (x/÷1.39) | (x/÷1.59) | |

| Eotaxin | 24 | 331 | 25769 | 139 |

| (x/÷3.7) | (x/÷2.49) | (x/÷3.33) | (x/÷2.35) | |

| MDC | 25263 | 835 | 199109 | 338 |

| (x/÷1.3) | (x/÷5.11) | (x/÷1.91) | (x/÷3.72) |

| Chemokines . | RLH . | Hodgkin’s MC . | Hodgkin’s NS . | Hodgkin’s NLP . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IP-10 | 4559 | 174159 | 7888 | 17074 |

| (x/÷1.6) | (x/÷1.17) | (x/÷2.47) | (x/÷1.82) | |

| Mig | 4648 | 612873 | 75030 | 168569 |

| (x/÷5.8) | (x/÷1.13) | (x/÷1.82) | (x/÷1.63) | |

| MIP-1α | 6989 | 73063 | 17665 | 14904 |

| (x/÷1.8) | (x/÷1.36) | (x/÷2.41) | (x/÷1.65) | |

| RANTES | 70104 | 342983 | 567879 | 92309 |

| (x/÷1.6) | (x/÷1.77) | (x/÷1.39) | (x/÷1.59) | |

| Eotaxin | 24 | 331 | 25769 | 139 |

| (x/÷3.7) | (x/÷2.49) | (x/÷3.33) | (x/÷2.35) | |

| MDC | 25263 | 835 | 199109 | 338 |

| (x/÷1.3) | (x/÷5.11) | (x/÷1.91) | (x/÷3.72) |

Numerical values represent geometric means of normalized pixels/disease subtype (x/÷ SEM).

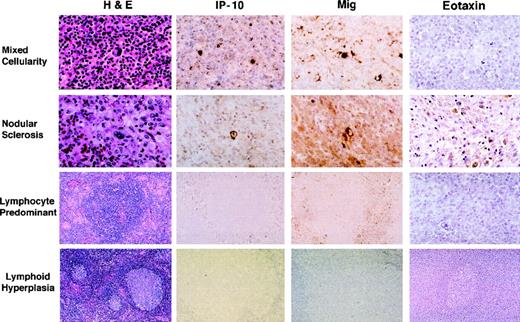

Paraffin-embedded sections sequential to those used for RNA extractions were stained with a rabbit antiserum to either human IP-10 or Mig. All HD tissues studied (Table 2), representative of the MC subtype (6 cases), the NS subtype (9 cases), and the NLP subtype (5 cases) stained positively for IP-10 and Mig, albeit with variations in intensity (Fig 4). Consistent with the results of RT-PCR analysis, staining for these chemokines was generally more prominent in MC cases than in the other two histologic subtypes. Control RLH tissues generally did not stain or stained very faintly for IP-10 and Mig (Fig 4). In general, HD tissue staining for these chemokines was intracellular, the patterns of staining for IP-10 and Mig were indistinguishable, and positivity for Mig was somewhat more intense than for IP-10. The brightest cells staining for Mig and IP-10 were identified morphologically as RS and Hodgkin’s cells. In general, staining appeared to be more intense in RS cells in EBV positive versus EBV negative cases. Other cells staining less intensely for these chemokines were identified morphologically as endothelial cells lining capillary vessels, macrophages, lymphocytes, and occasionally, fibroblasts. These results document the presence of IP-10 and Mig proteins in HD tissues and identify the RS and Hodgkin’s cells as positive for these chemokines.

Immunohistochemical analysis of IP-10, Mig, and eotaxin protein expression in HD tissues: MC, NS, and NLP, and lymphoid hyperplasia. Paraffin-embedded tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), an anti-IP–10 heteroantiserum (IP-10), an anti-Mig heteroantiserum (Mig), and an antieotaxin heteroantiserum (eotaxin). Primary antibodies were detected with biotinylated antirabbit IgG, followed by streptavidin-peroxidase complexes.

Immunohistochemical analysis of IP-10, Mig, and eotaxin protein expression in HD tissues: MC, NS, and NLP, and lymphoid hyperplasia. Paraffin-embedded tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), an anti-IP–10 heteroantiserum (IP-10), an anti-Mig heteroantiserum (Mig), and an antieotaxin heteroantiserum (eotaxin). Primary antibodies were detected with biotinylated antirabbit IgG, followed by streptavidin-peroxidase complexes.

As detailed above, levels of eotaxin and MDC expression in HD tissues did not correlate with evidence of tissue infection with EBV. Because eotaxin has been reported to serve as a specific chemoattractant for eosinophils, we examined whether a correlation existed between the degree of tissue infiltration with eosinophils and levels of eotaxin expression in HD tissues. Levels of eosinophil infiltration were estimated without knowledge of the results of PCR analysis by scoring histology slides stained with hematoxylin/eosin. A highly significant direct correlation (P = .0038) was identified between the extent of eosinophil infiltration (defined on the basis of the mean number of eosinophils/high powered field) and levels of HD tissue expression of eotaxin (Fig 5). By contrast, no significant direct correlation was identified between tissue eosinophilia and levels of expression of IP-10, Mig, MIP-1α, and RANTES. As a group, the NS subtype displayed both the highest levels of tissue eosinophilia and of eotaxin expression when compared with the other subtypes (Table 3). Although levels of MDC expression in HD tissues, as a group, were found not to differ significantly from those of RLH tissues (P = .7, Fig 2), within HD subtypes, MDC expression was significantly higher in the NS subtype as compared with the other subtypes (P = .002, Table 3).

Correlation of eotaxin mRNA expression and grade of tissue eosinophilia in HD. Tissue eosinophilia was quantified by counting the mean number of eosinophils/high powered field (at least 20 high powered fields were examined in each specimen). Tissue samples were classified as having 0 eosinophils/high powered field; 1 to 25 eosinophils/high powered field; or >25 eosinophils/high powered field.

Correlation of eotaxin mRNA expression and grade of tissue eosinophilia in HD. Tissue eosinophilia was quantified by counting the mean number of eosinophils/high powered field (at least 20 high powered fields were examined in each specimen). Tissue samples were classified as having 0 eosinophils/high powered field; 1 to 25 eosinophils/high powered field; or >25 eosinophils/high powered field.

Paraffin-embedded sections sequential to those used for RNA extractions were stained with a rabbit antiserum to eotaxin, including HD tissues representative of the MC (5 cases), NS (7 cases), and NLP (4 cases) subtypes, as well as control RLH tissues (9 cases). Consistent with RT-PCR results, eotaxin protein expression was generally more intense in the NS subtype (3 cases) compared with the other subtypes and control RLH. Cells staining for eotaxin were identified morphologically as RS and Hodgkin’s cells, fibroblasts, macrophages, lymphocytes, and medial smooth muscle cells of medium and large-sized vessels (Fig 4).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we have explored a potential role for chemokines in the pathobiology of HD. Overall, HD tissues displayed higher levels of expression of the chemokines IP-10, Mig, MIP-1α, RANTES, and eotaxin, but not MDC, when compared with lymph node tissues diagnosed with RLH. Within HD tissues, we found major differences in chemokine gene expression among the different disease subtypes. Mig and IP-10 were expressed at significantly higher levels in the MC subtype compared with the other subtypes, whereas eotaxin and MDC were expressed preferentially in the NS subtype. RANTES expression was high in both the MC and NS subtypes, and Mig was high in the NLP subtype.

On the basis of previous studies6,7 in athymic mice that had identified a pattern of chemokine response induced by EBV-infected, but not uninfected, B cells, we looked for differences of chemokine expression in EBV-positive and negative HD tissues. Similar to the situation in mice,6 7 we found levels of IP-10, Mig, and RANTES to be higher in EBV-positive than in EBV-negative HD tissues. MIP-1α expression also was significantly higher in EBV-positive than in EBV-negative HD tissues. By contrast, eotaxin and MDC expression levels were similar in HD tissues with or without evidence of EBV infection. When we analyzed the potential relationship between eotaxin expression and eosinophil infiltration, a highly significant correlation emerged, suggesting that eotaxin is a critical mediator of eosinophil recruitment in HD tissues.

Several factors have been proposed to promote eosinophil attraction, including platelet activating factors, RANTES, IL-16, MCP3, MCP4, myeloid progenitor inhibitory factors 1 and 2 (MPIF-1 and 2), hemofiltrate C-C chemokine-2 (HCC-2), secretoneurin, eotaxin, and eotaxin-2.13-23 The latter two chemokines have received considerable attention because, unlike all other factors, they appear to signal through a single receptor, CCR3, that is expressed at high levels on eosinophils and T-helper cells, but is not expressed on neutrophils or monocytes.18 24-29 This observation might explain why we observe a rich eosinophilic and T-cell inflammatory infiltrate in HD tissues where there is increased eotaxin expression.

These results suggest that, in addition to its previously recognized functions in allergic and inflammatory disorders,30-33eotaxin is likely to play an important role in promoting eosinophil recruitment to HD tissues.

Previous studies have documented production of abnormally high levels of IFN-γ and various cytokines in HD.1-4 Because some of these mediators can play an important role in regulation of chemokine production, it is not surprising that we found high level expression of certain chemokines in HD tissues. Expression of IP-10 and Mig that are IFN-γ inducible chemokines is consistent with the previously recognized abundance of IFN-γ in HD.1,34,35 Expression of eotaxin, which is inducible by IL-3,17 is consistent with increased IL-3 levels reported in this malignancy (data not shown).4 However, predictions on chemokine expression are difficult, particularly in situations, such as HD, in which abnormal or unbalanced production involves so many cytokines that participate in complex networks.

The CXC chemokines, IP-10 and Mig, share a common receptor, CXCR3, which is expressed on T and NK cells, but is undetectable on monocyte/macrophages, neutrophils, B cells, and endothelial cells.36,37 Accordingly, IP-10 and Mig are chemoattractants for T and NK cells.37 Based on this information, one might expect greater levels of infiltration with T, NK, and other cells in EBV-positive than in EBV-negative HD tissues. However, previous studies have failed to identify histologic and immunohistochemical differences between EBV-positive and EBV-negative HD, except those expected from the different frequencies of EBV infection in the MC (60% to 70%), NS (about 40%), and NLP (usually EBV negative) subtypes. Of note, one study suggested that EBV-positivity or latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1) protein expression was a favorable prognostic factor in HD,38 a result that is consistent with the known antitumor effects of IP-10 and Mig.6,7 39

Immunohistochemical studies localized IP-10 and Mig to Hodgkin’s and RS cells and to some surrounding inflammatory cells. We know that virtually all Hodgkin’s and RS cells are infected with EBV in virus-positive HD cases and display a type II virus latency, with expression of EBNA1 and LMP1 proteins, but not other EBV latency proteins.4,40,41 LMP1, an integral membrane protein, is emerging as a multifunctional protein that plays a critical role in EBV immortalization and is responsible for many of the phenotypic changes characteristic of EBV-immortalized cells. Because LMP-1 serves as a potent activator of the transcription factor NF-κB,42-44it may promote the production of a variety of cytokines and chemokines, including IP-10, Mig, RANTES, and MIP1-α, genes that contain κB elements. In athymic mice, we found that LMP1 expression alone in EBV-negative Burkitt cells induced a host response that included production of murine IP-10 and Mig.39 Thus, LMP1 is likely to represent an important inducer of IP-10 and Mig expression within the EBV-infected Hodgkin’s and RS cells, as well as by other inflammatory cells reactive to the neoplastic cells.

Expression of MDC mRNA has been shown to be enhanced by IL-1α, TNF-α, and lipopolysaccharide (LPS)45 and can promote chemoattraction of monocytes, monocyte-derived dendritic cells, and NK cells acting through the CCR4 receptor.46 It is intriguing that MDC is expressed at markedly high levels in the NS subtype of HD, and this result will require further investigation.

The abundance of inflammatory cells surrounding few neoplastic cells and the associated abnormal or unbalanced production of cytokines have been interpreted as reflective of an intense, but ineffective, antitumor response.4 HD patients display a variety of T-cell immune defects, including the absence of CD8-positive T cells surrounding the neoplastic cells and a failure to develop LMP-1–specific cytotoxic cells that may allow RS and Hodgkin’s cells to escape immune destruction.4 Nevertheless, patients with HD do not develop systemic EBV-positive lymphoproliferative disease, as may be observed in cases of congenital or acquired severe T-cell immunodeficiency. One interesting feature of the T cells infiltrating the neoplastic cells in HD is their failure to express the activation marker CD26 molecule that possesses dipeptidyl peptidase IV activity.4 Recently, it was found that chemokines can serve as substrates for CD26.47 Once truncated by CD26, chemokines can display functional differences from the native molecules, suggesting that CD26 processing may represent an important physiological mechanism for regulation of chemokine function.47

Thus, in addition to other previously reported immune abnormalities, the results presented here provide evidence for the occurrence of broad chemokine expression in HD tissues that could explain some of the characteristic cellular infiltrates in the different subtypes. Persistent chemokine stimulation by EBV and other stimuli combined with a potentially defective chemokine processing mechanism may contribute to a stagnant antitumor response in HD.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Dr Barry Cherney, Jared Berkowitz, and Karen Jones for laboratory assistance; Andrew Weiss for technical assistance with EBV in situ hybridizations; and Dr Laszlo Krenacs, Dr Xu Yao, and Dr Leticia Quintanilla-Fend for technical advice and assistance with immunohistochemical analyses.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to Julie Teruya-Feldstein, MD, Hematopathology Section, Laboratory of Pathology, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bldg 10, Room 2A33, 10 Center Dr, MSC 1500, Bethesda, MD 20892-1500; e-mail: jtf@helix.nih.gov.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal