Abstract

Retinoic acid (RA) resistance is a serious problem for patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) who are receiving all-transRA. However, the mechanisms and strategies to overcome RA resistance by APL cells are still unclear. The biologic effects of RA are mediated by two distinct families of transcriptional factors: RA receptors (RARs) and retinoid X receptors (RXRs). RXRs heterodimerize with 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3[1,25(OH)2D3] receptor (VDR), enabling their efficient transcriptional activation. The cyclin-dependent kinase (cdk) inhibitor p21WAF1/CIP1 has a vitamin D3–responsive element (VDRE) in its promoter, and 1,25(OH)2D3 enhances the expression of p21WAF1/CIP1 and induces differentiation of selected myeloid leukemic cell lines. We have recently established a novel APL cell line (UF-1) with features of RA resistance. 1,25(OH)2D3 can induce growth inhibition and G1 arrest of UF-1 cells, resulting in differentiation of these cells toward granulocytes. This 1,25(OH)2D3-induced G1 arrest is enhanced by all-trans RA. Also, 1,25(OH)2D3 (10−10 to 10−7 mol/L) in combination with RA markedly inhibits cellular proliferation in a dose- and time-dependent manner. Associated with these findings, the levels of p21WAF1/CIP1 and p27KIP1 mRNA and protein increased in these cells. Northern blot analysis showed that p21WAF1/CIP1 and p27KIP1 mRNA and protein increased in these cells. Northern blot analysis showed that p21WAF1/CIP1 and p27KIP1 transcripts were induced after 6 hours’ exposure to 1,25(OH)2D3 and then decreased to basal levels over 48 hours. Western blot experiments showed that p21WAF1/CIP1 protein levels increased and became detectable after 12 hours of 1,25(OH)2D3treatment and induction of p27KIP1 protein was much more gradual and sustained in UF-1 cells. Interestingly, the combination of 1,25(OH)2D3 and RA markedly enhanced the levels of p27KIP1 transcript and protein as compared with levels induced by 1,25(OH)2D3 alone. In addition, exogenous p27KIP1 expression can enhance the level of CD11b antigen in myeloid leukemic cells. In contrast, RA alone can induce G1 arrest of UF-1 cells; however, it did not result in an increase of p21WAF1/CIP1 and p27KIP1transcript and protein expression in RA-resistant cells. Taken together, we conclude that 1,25(OH)2D3 induces increased expression of cdk inhibitors, which mediates a G1 arrest, and this may be associated with differentiation of RA-resistant UF-1 cells toward mature granulocytes.

RETINOIC ACID (RA) and vitamin D3 have profound effects on the growth and differentiation of hematopoietic cells, as well as other cell types.1-3All-trans RA and its stereoisomer, 9-cis RA, induce differentiation and inhibit proliferation of human leukemic cell lines such as HL-60 cells and fresh leukemic cells from patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL).3-6 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 [1,25(OH)2D3] is a biologic active form of vitamin D3 that functions primarily in calcium homeostasis in vitro. 1,25(OH)2D3 can also induce some myeloid leukemic cell lines to differentiate along the monocyte/macrophage pathway and can prolong the survival of leukemic mice.7,8 These biologic effects of RA and 1,25(OH)2D3 are mediated by their respective nuclear receptors, retinoic acid receptor (RAR), retinoid X receptor (RXR), and vitamin D3 receptor (VDR).9 They are members of the steroid receptor superfamily and act as ligand-inducible transcription factors by binding to their cognate responsive DNA elements, termed the RA-responsive element (RARE) and vitamin D3–responsive element (VDRE).10-12 RAR and VDR heterodimerize with RXR to bind DNA with high affinity and effect efficient transcriptional activation of target genes.13-15

Inhibition of the G1/S transition induces growth arrest and monocytic differentiation of both HL-60 and U937 cells, which is mediated by a block of cell cycle progression at the G1 phase.16,17 The p21WAF1/CIP1 protein is a cyclin-dependent kinase (cdk) inhibitor that is one of the regulators of cell cycle progression in the G1/S transition. Exposure of HL-60 cells to 1,25(OH)2D3 causes transient overexpression of p21WAF1/CIP1.17 Further studies showed that the p21WAF1/CIP1 promoter contains a VDRE, and exposure of U937 myelomonoblasts to 1,25(OH)2D3results in transcriptional activation of p21WAF1/CIP1, probably through a ligand/VDR/VDRE interaction.18 Another report has suggested that p27KIP1 protein is also a strong candidate as a cell cycle regulator that blocks the entry into S phase of 1,25(OH)2D3-treated HL-60 cells.19

Several clinical studies have recently reported that all-transRA achieved a complete remission in most patients with APL via an induction of differentiation of the leukemic cells in vivo.20-23 Nevertheless, most patients who received continuous treatment with RA relapsed and developed RA-resistant disease.24 However, the mechanisms and strategies to overcome RA resistance by APL cells are still unclear. Recently, we established a novel APL cell line (UF-1) with RA-resistant features that can be used as a model for studies on RA resistance in APL cells.25 In this study, we report that 1,25(OH)2D3 can overcome RA resistance in this model system of APL.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and chemicals.

The RA-resistant UF-1 promyelocytic leukemia cell line was established in our laboratory from a patient with APL in relapse who had received all-trans RA.25 HL-60 and NB4 promyelocytic cells are RA-responsive leukemic cells (the latter being a gift from Dr M. Lanotte, Hôpital St Louis, Paris, France).26 The cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (GIBCO-BRL; Grand Island, NY) with 10% fetal calf serum ([FCS] Hyclone Laboratories, Logan, UT), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 mg/mL streptomycin in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. All-trans RA was purchased from Sigma Chemical Co (St Louis, MO), and 1,25(OH)2D3 was a generous gift from Chugai Pharmaceutical Co (Tokyo, Japan). They were dissolved in 100% ethanol to a stock concentration of 1 mmol/L, stored at −20°C, and protected from light. The morphology and cytochemistry of the cells were evaluated from cytospin slide preparations with Giemsa and naphthol AS-D chloroacetate esterase staining.

Assays for cellular proliferation.

Cellular proliferation was measured by cell viability and a nonradioactive cell proliferation assay system (MTT assay; Boehringer-Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN). Cells (2 × 103) were incubated with chemicals for 4 days in 96-well plates (Flow Laboratories, Irvine, CA). Ten microliters of MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazole-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide, 5 μg/mL) was added to each well. The reaction was stopped after 4 hours of incubation by adding 100 μL 0.04N HCl in isopropanol, and absorbance at 570 nm was determined.

Flow cytometric analysis.

For analysis of cellular differentiation, expression of cell-surface antigens was determined by an immunofluorescence staining technique. Cells were incubated for 30 minutes with human AB serum (Sigma) to block Fc receptors and then stained using fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated mouse anti–human CD14 and phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated mouse anti–human CD11b antibodies (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA). Control studies were performed with nonbinding control mouse IgG1 and IgG2a isotype antibodies (Becton Dickinson). Cells were analyzed by a Cytron Absolute Flow Cytometer (Ortho Diagnostic Systems, Raritan, NJ).

Cell cycle analysis.

Cells (1 × 106) were suspended in hypotonic solution (0.1% Triton X-100, 1 mmol/L Tris hydrochloride, pH 8.0, 3.4 mmol/L sodium citrate, and 0.1 mmol/L EDTA) and stained with 5 μg/mL propidium iodide. Analysis was performed immediately after staining using the CELLFIT program (Becton Dickinson).

RNA isolation and Northern blotting.

Total RNA was extracted using the Isogen kit (Nippon Gene, Tokyo, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Total RNA (15 μg per lane) was electrophoresed on formaldehyde-agarose gels (GIBCO-BRL) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Hybond N+; Amersham Japan, Tokyo, Japan). The filters were hybridized with32P-labeled probe for 24 hours at 42°C in 50% formamide, 2X SSC (1X SSC is 150 mmol/L NaCl plus 15 mmol/L sodium citrate, pH 7.0), 5X Denhardt solution, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 10% dextran sulfate, and 100 μg/mL salmon sperm DNA. Filters were washed to a stringency of 0.1X SSC at 65°C and exposed to Kodak XAR film (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY). Autoradiograms were exposed for 24 hours to 3 days. Densitometry was performed for signal intensity on autoradiograms of Northern blots using a digital densitometer.

DNA probes.

The plasmid containing human p21WAF1/CIP1 cDNA (NotI-NotI; 2.1 kb) was kindly provided by Dr B. Vogelstein (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD),27 and the human p27KIP1 cDNA was purified from the pBluescript II SK plasmid (EcoRI-EcoRI, 1.5 kb; a gift from Dr J. Massagué, Memorial-Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY).28 These probes were labeled with [α-32P]dCTP using the rediprime DNA labeling system (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL). The specific activity was approximately 2 × 108 cpm/μg DNA.

Western blotting.

Cells were collected by centrifugation at 1,200 rpm for 10 minutes, and then the pellets were resuspended in lysis buffer (1% Nonidet P-40, 1 mmol/L, 40 mmol/L Tris hydrochloride, pH 8.0, and 150 mmol/L NaCl) at 4°C for 15 minutes. Protein concentrations were determined using the Bio-Rad protein assay system (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA). Cell lysates (10 μg protein per lane) were fractionated in 12.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gels before transfer to the membrane (Immobilon-P membranes; Millipore, Bedford, MA) by standard protocol. The membrane was blocked overnight with 5% defatted milk in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 4°C. The anti-p21WAF1/C1P1 -p27KIP1, -p15INK4B, and -p16INK4Aantibodies (Calbiochem, Cambridge, MA) were used at 1:1,000 dilution in 5% defatted milk in PBS for 1 hour at 25°C. Subsequently, membranes were incubated with anti–rabbit Ig conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (1:3,000; Amersham) for 1 hour at 25°C. All steps were followed by three washes for 5 minutes in PBS, 1% defatted milk, and 0.2% Tween 20. Antibody binding was detected using the enhanced chemiluminescence kit for Western blotting detection with hyper-ECL film (Amersham). Blots were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue and confirmed to contain a similar amount of protein extract on each lane.

Plasmid and transfection.

The full-length human p27KIP1 cDNA plasmid (pBluescript II SK-hp27) was used as the template in a polymerase chain reaction to amplify the human p27KIP1 cDNA fragment (codons 2 to 199) that was cloned into the BglII andBamHI sites of the pEGFP-C1 expression vector (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA), which contains a cytomegalovirus (CMV) IE promoter and green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter gene. The resultant plasmid was designated pEGFP-hKIP1. The pEGFP-neo was used as a control plasmid. Exponentially growing cells were suspended in RPMI 1640 containing 10% FCS at a density of 2 × 107/mL. Cells were transfected with plasmids by electroporation using a Gene Pulser II (Bio-Rad) set at 240 V, 1,000 μF. A pulse was delivered to 300 μL cell suspension and 30 μg plasmid DNA. After 48 hours of electroporation, cells were stained with PE-conjugated mouse anti-human CD11b antibody (Becton Dickinson) and analyzed for CD11b positive cells in the GFP-positive fraction by two-color flow cytometry.

RESULTS

Morphologic changes induced in RA-resistant APL cells (UF-1) cultured with 1,25(OH)2D3.

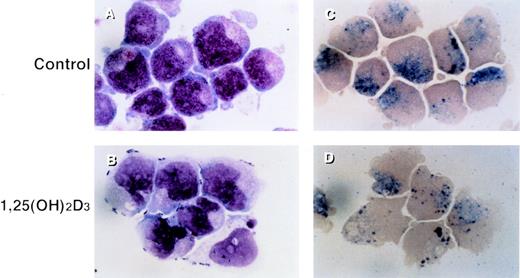

UF-1 cells in control cultures showed large round nuclei and numerous granules in the cytoplasm, as found with hypergranulocytic promyelocytes (Fig 1A). Incubation with 10−7 mol/L 1,25(OH)2D3 for 4 days resulted in differentiation of UF-1 cells, as evidenced by nuclear maturation and lobulation, and a diminished number of granules in the cytoplasm (Fig 1B). Naphthol AS-D chloroacetate esterase was positive for both control and 1,25(OH)2D3-treated UF-1 cells (Fig 1C and D), consistent with these cells being of the granulocytic lineage.

Morphologic and cytochemical changes in RA-resistant APL cells by 1,25(OH)2D3. UF-1 cells were cultured with either 10−7 mol/L 1,25(OH)2D3 (B and D) or culture media alone (A and C) for 4 days, and cytospin slides were prepared and stained with either Giemsa (A and B) or naphthol AS-D chloroacetate esterase (C and D). Original magnification ×1,000.

Morphologic and cytochemical changes in RA-resistant APL cells by 1,25(OH)2D3. UF-1 cells were cultured with either 10−7 mol/L 1,25(OH)2D3 (B and D) or culture media alone (A and C) for 4 days, and cytospin slides were prepared and stained with either Giemsa (A and B) or naphthol AS-D chloroacetate esterase (C and D). Original magnification ×1,000.

Effects of 1,25(OH)2D3 on cellular proliferation of UF-1 cells.

UF-1 cells were cultured in the presence of various concentrations of 1,25(OH)2D3 (10−10 to 10−7 mol/L) with or without all-trans RA (10−7 mol/L) for 4 days (Fig2A) or treated with the indicated agents for different times (Fig 2B). As previously reported,25all-trans RA alone did not effect growth of UF-1 cells, as reflected by a lack of change in their absorbance in the MTT assay. In contrast, 1,25(OH)2D3 inhibited the cellular proliferation and decreased the number of viable cells in a dose (10−10 to 10−7 mol/L)- and time (0 to 96 hours)-dependent manner. Interestingly, the combination of 10−7 mol/L all-trans RA and 1,25(OH)2D3 markedly inhibited cell growth in a dose- and time-dependent manner (Fig 2A and B). We next examined the effect of 1,25(OH)2D3 and all-trans RA on cell cycle progression in UF-1 cells. The cells were incubated with either 10−7 mol/L all-transRA, 1,25(OH)2D3, or a combination of both for 48 hours and analyzed for cell cycle distribution by flow cytometry (Table 1). Cultivation with 1,25(OH)2D3 for 48 hours increased the population of cells in G1 phase from 80.2% to 93.3% with a reduction of cells in S phase from 13.8% to 5.0%. Consistent with the cellular proliferation assay, the combination of all-trans RA and 1,25(OH)2D3 significantly increased the number of cells in the G1 phase of the cell cycle (98.4%) compared with control cells (80.2%), with a concomitant decrease in the S phase (Table 1). These increased populations of G1 phase in 1,25(OH)2D3-treated cells represent G1-arrested cells.

Dose- and time-dependent effects of 1,25(OH)2D3 and/or all-trans RA on cellular proliferation of UF-1 cells. RA-resistant UF-1 cells were cultured in 96-well plates with various concentrations (10−10 to 10−7 mol/L) of 1,25(OH)2D3 for 4 days (A) or for different times (0-96 hours) with the indicated compounds (B), and then MTT incorporation was measured. Absorbance at 570 nm (OD570) was recorded using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay plate reader. Results are presented as the mean of triplicate experiments; the SD was within 10% of the mean.

Dose- and time-dependent effects of 1,25(OH)2D3 and/or all-trans RA on cellular proliferation of UF-1 cells. RA-resistant UF-1 cells were cultured in 96-well plates with various concentrations (10−10 to 10−7 mol/L) of 1,25(OH)2D3 for 4 days (A) or for different times (0-96 hours) with the indicated compounds (B), and then MTT incorporation was measured. Absorbance at 570 nm (OD570) was recorded using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay plate reader. Results are presented as the mean of triplicate experiments; the SD was within 10% of the mean.

Cell Cycle Analysis of UF-1 Cells

| Treatment . | % Fluorescence at Cell Cycle Phase: . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| G0/G1 . | S . | G2/M . | |

| Control | 80.2 | 13.8 | 6.0 |

| All-transRA | 91.9 | 6.7 | 1.5 |

| 1,25(OH)2D3 | 93.3 | 5.0 | 1.7 |

| 1,25(OH)2D3+ all-trans RA | 98.4 | 0.5 | 1.1 |

| Treatment . | % Fluorescence at Cell Cycle Phase: . | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| G0/G1 . | S . | G2/M . | |

| Control | 80.2 | 13.8 | 6.0 |

| All-transRA | 91.9 | 6.7 | 1.5 |

| 1,25(OH)2D3 | 93.3 | 5.0 | 1.7 |

| 1,25(OH)2D3+ all-trans RA | 98.4 | 0.5 | 1.1 |

UF-1 cells were cultured with either 10−7 mol/L all-trans RA, 10−7 mol/L 1,25(OH)2D3, or a combination of both for 48 hours. DNA was stained with propidium iodide, and analysis was immediately performed using the CELLFIT program.

Functional evidence for differentiation of UF-1 cells to granulocytes by 1,25(OH)2D3.

Induction of the differentiation of UF-1 cells to granulocytes by 1,25(OH)2D3 was assessed by the expression of CD11b and CD14 antigens (Figs 3 and4). All-trans RA (10−7 mol/L) did not alter the expression of CD11b and CD14 antigens by fluorescent-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis compared with control cells. 1,25(OH)2D3(10−9 to 10−7 mol/L) induced CD11b positive cells in a dose-dependent manner from 1% to 66%. The combination of various concentrations of 1,25(OH)2D3 plus all-trans RA (10−7 mol/L) greatly enhanced the expression of CD11b antigen as compared with either agent alone. However, expression of CD14 antigen was unchanged after exposure to either 1,25(OH)2D3 alone or the combination of RA and 1,25(OH)2D3 (Figs 3 and 4). These results are consistent with the morphologic and cytochemical studies, suggesting that 1,25(OH)2D3 induces differentiation of UF-1 cells down the granulocytic pathway and RA can enhance this effect.

Expression of CD11b and CD14 antigens by FACS analysis. UF-1 cells were treated with either 10−7 mol/L all-trans RA, various concentrations (10−9 to 10−7 mol/L) of 1,25(OH)2D3, or combinations of both for 4 days. Cells were incubated for 30 minutes with human AB serum to block Fc receptors and then stained with direct immunofluorescence using FITC-conjugated mouse anti–human CD14 and PE-conjugated mouse anti–human CD11b antibodies. Control studies were performed with nonbinding control mouse IgG1 and IgG2a isotype antibodies.

Expression of CD11b and CD14 antigens by FACS analysis. UF-1 cells were treated with either 10−7 mol/L all-trans RA, various concentrations (10−9 to 10−7 mol/L) of 1,25(OH)2D3, or combinations of both for 4 days. Cells were incubated for 30 minutes with human AB serum to block Fc receptors and then stained with direct immunofluorescence using FITC-conjugated mouse anti–human CD14 and PE-conjugated mouse anti–human CD11b antibodies. Control studies were performed with nonbinding control mouse IgG1 and IgG2a isotype antibodies.

Graphic representation of the FACS analysis of CD11b and CD14 antigens shown in Fig 3. Results show the differentiation-inducing activities of all-trans RA, 1,25(OH)2D3, and the combination of both chemicals.

Graphic representation of the FACS analysis of CD11b and CD14 antigens shown in Fig 3. Results show the differentiation-inducing activities of all-trans RA, 1,25(OH)2D3, and the combination of both chemicals.

Expression of p21WAF1/CIP1 and p27KIP1 mRNA in HL-60, NB4, and UF-1 cells.

1,25(OH)2D3 induced the differentiation of UF-1 cells in association with a block of cell cycle progression at the G1 phase. Therefore, to address the mechanisms of action of 1,25(OH)2D3 on RA-resistant APL cells, we examined the expression of cdk inhibitors in UF-1 cells. 1,25(OH)2D3 can induce HL-60 cells to differentiate into monocyte/macrophage-like cells. Forty-eight hours’ incubation of 1,25(OH)2D3 (10−7mol/L) was sufficient to commit HL-60 cells to differentiate along the monocyte/macrophage pathway (data not shown). HL-60 cells were cultured for 48 hours in the presence of 10−7 mol/L 1,25(OH)2D3, and then the expression of p21WAF1/CIP1 and p27KIP1transcripts was examined by Northern blotting (Fig5). Low levels of p21WAF1/CIP1 mRNA were detected in the control cells, whereas the accumulation of p21WAF1/CIP1mRNA increased after the cells were exposed to 1,25(OH)2D3, suggesting that the induction of p21WAF1/CIP1 was associated with the induction of differentiation of HL-60 cells to monocytes/macrophages. NB4 cells are genetically different from HL-60 cells in that they possess a reciprocal chromosomal translation, t(15;17), which is characteristic of APL cells.26 NB4 cells respond to 1,25(OH)2D3 differently from HL-60 cells. Recent reports have shown that 1,25(OH)2D3alone failed to induce the differentiation of NB4 cells to monocytes/macrophages.29 30 In NB4 cells, p21WAF1/CIP1 mRNA was not detectable constitutively, and 1,25(OH)2D3 did not enhance the expression of these transcripts. In contrast, constitutive expression of p21WAF1/CIP1 and p27KIP1 transcripts was observed in RA-resistant UF-1 cells, and the levels of p21WAF1/CIP1 and p27KIP1 transcripts were not changed after 48 hours’ exposure to all-trans RA (10−7 mol/L) but were slightly increased after 48 hours’ exposure to 1,25(OH)2D3 (10−7 mol/L) (Fig 5).

Expression of p21WAF1/CIP1 mRNA in HL-60 and NB4 cells, and p21WAF1/CIP1 and p27KIP1 transcripts in UF-1 cells. Cells were cultured with either 10−7 mol/L 1,25(OH)2D3 (A) or 10−7 mol/L all-trans RA (B) for 48 hours. Total RNA (15 μg per lane) was extracted and analyzed by Northern blot with [32P]-labeled p21WAF1/CIP1 or p27KIP1 cDNA probe. Bottom panel shows the ethidium bromide–stained formaldehyde gel before Northern blotting; the levels of 28S and 18S ribosomal RNA are comparable in each lane.

Expression of p21WAF1/CIP1 mRNA in HL-60 and NB4 cells, and p21WAF1/CIP1 and p27KIP1 transcripts in UF-1 cells. Cells were cultured with either 10−7 mol/L 1,25(OH)2D3 (A) or 10−7 mol/L all-trans RA (B) for 48 hours. Total RNA (15 μg per lane) was extracted and analyzed by Northern blot with [32P]-labeled p21WAF1/CIP1 or p27KIP1 cDNA probe. Bottom panel shows the ethidium bromide–stained formaldehyde gel before Northern blotting; the levels of 28S and 18S ribosomal RNA are comparable in each lane.

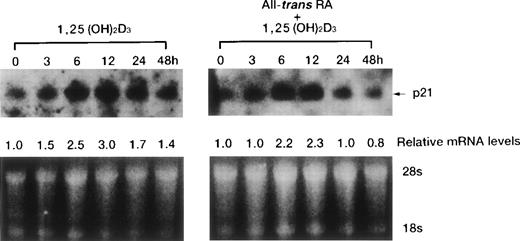

Time course of p21WAF1/CIP1 and p27KIP1 induction by 1,25(OH)2D3.

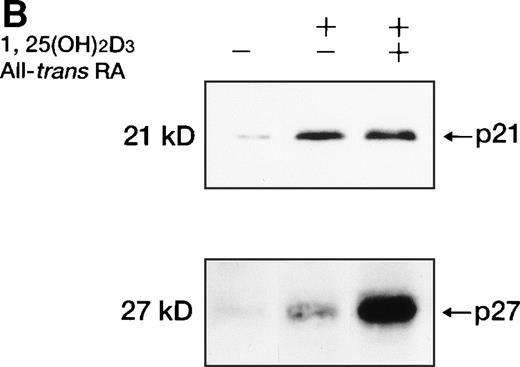

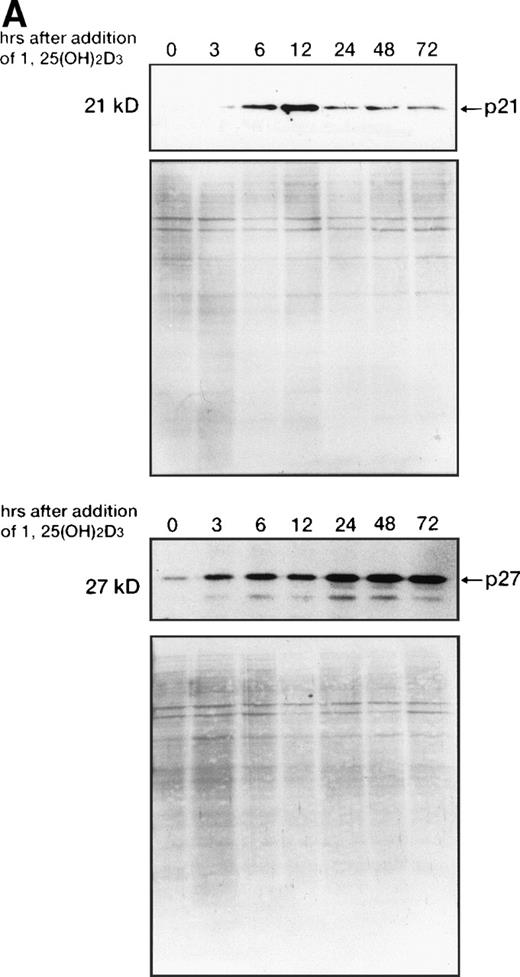

1,25(OH)2D3-induced expression of cdk inhibitor p21WAF1/CIP1 was examined more closely by comparing transcript and protein levels over a time frame of 0 to 72 hours following the addition of 1,25(OH)2D3 either with or without all-trans RA to UF-1 cells (Figs6, and 8A and B). The related cdk inhibitor p27KIP1 was also included in this analysis (Figs7 and 8A and B). The levels of p21WAF1/CIP1 and p27KIP1transcripts increased about twofold after 6 hours of exposure to 1,25(OH)2D3, and then the expression decreased toward baseline levels over the remaining 42 hours (Figs 6 and 7). Western blot experiments showed that p21WAF1/CIP1protein levels became detectable after 6 hours and peaked at 12 hours of 1,25(OH)2D3 (10−7 mol/L) treatment. The level of p27KIP1 protein increased by 3 hours and continued to increase at 72 hours of culture with 1,25(OH)2D3 (10−7 mol/L) (Fig8A). The dissociation between the early and transient mRNA induction of p27KIP1 and the late and sustained appearance of the corresponding protein suggests that posttranscriptional regulation is imposed on this cdk inhibitor.

Time course of p21WAF1/CIP1 mRNA induction of expression by either 1,25(OH)2D3alone or combined with RA in UF-1 cells. Cells were cultured for various durations (0 to 48 hours) with 10−7 mol/L 1,25(OH)2D3 (left) or 10−7 mol/L of both RA and 1,25(OH)2D3 (right). Northern blot analysis of p21WAF1/CIP1 mRNA was performed by blotting total RNA (15 μg per lane). Equal loading of RNA in each lane was confirmed by ethidium bromide staining of the formaldehyde gel; thus, the densitometric reading for the relative levels of p21WAF1/CIP1 transcript was compared with that of untreated cells.

Time course of p21WAF1/CIP1 mRNA induction of expression by either 1,25(OH)2D3alone or combined with RA in UF-1 cells. Cells were cultured for various durations (0 to 48 hours) with 10−7 mol/L 1,25(OH)2D3 (left) or 10−7 mol/L of both RA and 1,25(OH)2D3 (right). Northern blot analysis of p21WAF1/CIP1 mRNA was performed by blotting total RNA (15 μg per lane). Equal loading of RNA in each lane was confirmed by ethidium bromide staining of the formaldehyde gel; thus, the densitometric reading for the relative levels of p21WAF1/CIP1 transcript was compared with that of untreated cells.

Time-dependent effects of either 1,25(OH)2D3 alone or in combination with RA on levels of p27KIP1 mRNA in UF-1 cells. Cells were cultured for the indicated durations with either 10−7mol/L 1,25(OH)2D3 alone or in combination with 10−7 mol/L RA. Total RNA (15 μg per lane) was blotted and hybridized with a p27KIP1 cDNA probe. Bottom panel shows the ethidium bromide–stained gel with 28S and 18S ribosomal RNA demonstrating equivalent RNA-loading per lane. Expression of p27KIP1 transcripts relative to the expression in control cells was determined by densitometry.

Time-dependent effects of either 1,25(OH)2D3 alone or in combination with RA on levels of p27KIP1 mRNA in UF-1 cells. Cells were cultured for the indicated durations with either 10−7mol/L 1,25(OH)2D3 alone or in combination with 10−7 mol/L RA. Total RNA (15 μg per lane) was blotted and hybridized with a p27KIP1 cDNA probe. Bottom panel shows the ethidium bromide–stained gel with 28S and 18S ribosomal RNA demonstrating equivalent RNA-loading per lane. Expression of p27KIP1 transcripts relative to the expression in control cells was determined by densitometry.

Western blot analysis of p21WAF1/CIP1and p27KIP1 protein. (A) Total cellular protein (10 μg per lane) from UF-1 cells treated for 3-72 hours with 10−7 mol/L 1,25(OH)2D3 was separated on a 12.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred to the membrane. p21WAF1/CIP1 and p27KIP1 protein levels were detected by Western blotting using antibodies directed against p21WAF1/CIP1 and p27KIP1, and then the blots were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue to confirm that equal amounts of protein were present in each lane. (B) Enhanced expression of p27KIP1 protein by exposure of cells to the combination of 10−7 mol/L all-trans RA and 1,25(OH)2D3 for 48 hours.

Western blot analysis of p21WAF1/CIP1and p27KIP1 protein. (A) Total cellular protein (10 μg per lane) from UF-1 cells treated for 3-72 hours with 10−7 mol/L 1,25(OH)2D3 was separated on a 12.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred to the membrane. p21WAF1/CIP1 and p27KIP1 protein levels were detected by Western blotting using antibodies directed against p21WAF1/CIP1 and p27KIP1, and then the blots were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue to confirm that equal amounts of protein were present in each lane. (B) Enhanced expression of p27KIP1 protein by exposure of cells to the combination of 10−7 mol/L all-trans RA and 1,25(OH)2D3 for 48 hours.

All-trans RA combined with 1,25(OH)2D3did not further enhance the expression of p21WAF1/CIP1 mRNA and protein (Figs 6 and8B). However, p27KIP1 transcripts and proteins were strongly induced after 6 hours’ exposure to the combination of 1,25(OH)2D3 and all-trans RA compared with 1,25(OH)2D3 alone (Figs 7 and 8B). These findings paralleled the synergistic ability of these two ligands to induce the differentiation of UF-1 cells toward granulocytes. We also examined the ankyrin family of cdk inhibitors that includes p15INK4B and p16INK4A. However, these INK4 proteins were not detectable by Western blot analysis following 1,25(OH)2D3 treatment (data not shown).

Forced expression of p27KIP1 induces cellular differentiation of myeloid cells.

The results of our expression studies suggest an association of p27KIP1 expression and myeloid cell differentiation induced by 1,25(OH)2D3. To further explore this association, we constructed a GFP-p27KIP1 fusion protein–expressing plasmid (pEGFP-hKIP1) and a control plasmid (pEGFP-neo) and transfected them into myeloid leukemic cells. The slow-growing promyelocytic NB4 and UF-1 cells were impossible to transfect effectively; therefore, our experiments focused on HL-60 cells. This expression vector contains the GFP reporter gene, and thus, the plasmid-introduced cell population was positive for green fluorescence. The cell population that expressed green fluorescence was evaluated for differentiation by analysis of expression of the CD11b antigen by two-color flow cytometry. The transient expression of p27KIP1 in HL-60 cells resulted in a rightward shift of the fluorescence intensity compared with control vector-transfected cells (Fig 9). This clearly suggests that forced expression of p27KIP1can result in cellular differentiation of leukemic cells.

Flow cytometric analysis for markers of cellular differentiation on p27KIP1-transfected HL-60 cells. Cells were transiently transfected with either pEGFP-hKIP1 or pEGFP-neo control plasmid by electroporation. Transfected cells were cultured for 48 hours and then stained with PE-conjugated mouse anti–human CD11b antibody. Expression of CD11b antigen in the GFP-positive fraction was analyzed by two-color flow cytometry.

Flow cytometric analysis for markers of cellular differentiation on p27KIP1-transfected HL-60 cells. Cells were transiently transfected with either pEGFP-hKIP1 or pEGFP-neo control plasmid by electroporation. Transfected cells were cultured for 48 hours and then stained with PE-conjugated mouse anti–human CD11b antibody. Expression of CD11b antigen in the GFP-positive fraction was analyzed by two-color flow cytometry.

DISCUSSION

To date, the mechanisms of RA resistance in APL cells are still unclear, and most approaches have not been successful in overcoming RA resistance in vivo.31,32 Cell differentiation is regulated in a cell cycle–dependent manner; for example, differentiation of hematopoietic cells is associated with a loss of cell cycling capacity, and the cells become arrested in the G0/G1 phase of the cell cycle.33 Also, the principal block to cell cycle progression in 1,25(OH)2D3-treated human cells is known to occur in the G1 phase.16 34 In the present study, we showed that RA-resistant UF-1 cells differentiated toward granulocytes when cultured with 1,25(OH)2D3, and this was associated with the G1 arrest of these cells and an increased expression of the cdk inhibitors p21WAF1/CIP1 and p27KIP1. Consistent with the induction of p21WAF1/CIP1 and p27KIP1 transcripts in UF-1 cells after a short exposure to either 1,25(OH)2D3 or 1,25(OH)2D3 combined with all-trans RA, the inhibition of cellular proliferation occurred within 6 to 12 hours. These data suggest that an increase of p21WAF1/CIP1and p27KIP1 transcripts associates with cyclin-cdk complexes during the first 12 hours of exposure to 1,25(OH)2D3 and is capable of inhibiting the kinase activities with these complexes, leading to G0/G1 arrest and differentiation of the myeloid leukemic cells.

1,25(OH)2D3 transduces its signal through the DNA-binding transcription factor, VDR.9 Therefore, ligand-inducible effects on cell growth and differentiation are initiated through the direct activation or repression of target genes by VDR. Many genes are reportedly regulated by 1,25(OH)2D3; however, none of these genes have been shown to be direct targets for VDR regulation. Recently, Liu et al18 reported that the induced differentiation of the myelomonocytic leukemia cell line U937 by 1,25(OH)2D3 was facilitated by transcriptional stimulation of the p21WAF1/CIP1 gene by VDR. We demonstrated that 1,25(OH)2D3, but not all-trans RA, upregulated the expression of p21WAF1/CIP1 and p27KIP1transcripts and proteins in RA-resistant UF-1 cells during granulocytic differentiation. Also, prior studies showed that 1,25(OH)2D3 did not increase the accumulation of p21WAF1/CIP1 mRNA in RA-responsive NB4 cells; indeed, other biologic effects of 1,25(OH)2D3in NB4 cells may occur independently of VDR/VDRE action.35Furthermore, a transient elevation in the expression of p21WAF1/CIP1 and/or p27KIP1 in U937 cells in the absence of 1,25(OH)2D3 enhanced the expression of CD11b and CD14 antigens.18 Consistent with our study, several studies have linked the enhanced expression of p21WAF1/CIP1 in myeloid leukemic cells to their induced differentiation.16-18 34 These data suggest that 1,25(OH)2D3 induces increased expression of p21WAF1/CIP1 and p27KIP1, which mediates a G1 arrest; this may be closely associated with the terminal differentiation of myeloid leukemic cells.

Other studies have suggested that the cdk inhibitor p27KIP1 is the principal mediator of the antiproliferative action of 1,25(OH)2D3 on HL-60 cells, by showing that the induction of p27KIP1 but not p21WAF1/CIP1correlated with the onset of G1 arrest.19 We found in UF-1 cells that p21WAF1/CIP1 protein levels increased and became detectable after 12 hours of 1,25(OH)2D3 treatment, while the induction of p27KIP1 protein was much more gradual and sustained in UF-1 cells. Also, all-trans RA alone did not modulate the expression of p21WAF1/CIP1 and p27KIP1 transcripts. The combination of RA and 1,25(OH)2D3 cooperatively enhanced the levels of p27KIP1 transcript and protein but not p21WAF1/CIP1 mRNA and protein in UF-1 cells. Recently, Casaccia-Bonnefil et al36 reported that oligodendrocyte progenitor cells derived from p27KIP1-knockout mice showed impaired growth arrest and differentiation after removal of a mitogen in the culture, thus demonstrating for the first time that p27KIP1 is an important component of the machinery required for the G0/G1 transition. In addition, we demonstrated that exogenous expression of p27KIP1 in HL-60 cells can enhance the level of expression of the CD11b antigen, demonstrating directly the role of p27KIP1 in cellular differentiation. Taken together, p27KIP1 may be more important than p21WAF1/CIP1 for the G1 arrest and granulocytic differentiation of UF-1 cells induced by 1,25(OH)2D3.

Interestingly, all-trans RA greatly enhanced 1,25(OH)2D3-induced differentiation of UF-1 cells to granulocytes, whereas RA alone did not induce differentiation of the cells. Although all-trans RA alone was able to induce G1 arrest of UF-1 cells (Table 1), the reason it did not inhibit the cellular growth is unclear. All-trans RA alone did not upregulate the expression of p21WAF1/CIP1 and p27KIP1 in UF-1 cells, and therefore, induction of G1 arrest may be a necessary, but insufficient, condition for cellular differentiation in UF-1 cells. Cell cycle arrest and activation of cdk inhibitors may be important for induction of cellular differentiation. The mechanisms underlying acquired RA resistance in APL patients have remained elusive. Recent studies have shown that mutations in the ligand-binding domain of RARα or PML/RARα genes are related to the development of RA resistance in some patients with APL.37,38 Moreover, it has been reported that RA can dissociate the nuclear receptor corepressor/histone deacetylase complex from PML/RARα, which relieves transcriptional repression and leads to activation of genes involved in the terminal differentiation of APL cells.39-42 Since p21WAF1/CIP1 might be a transcriptional target of RARs, a RARE in the promoter region of the p21WAF1/CIP1 gene was required to confer RA-induced cellular differentiation.43 Taken together, our results suggest that the failure to induce cdk inhibitors by the ligand-activated RAR through RARE in the promoter region of their target genes may explain, in part, the RA resistance in UF-1 cells. Further studies will be needed to clarify the mechanisms of RA resistance and regulation of cdk inhibitors.

The combination of 1,25(OH)2D3 and all-trans RA enhanced p27KIP1 mRNA and protein in RA-resistant UF-1 cells. Our group and others have already reported the synergistic differentiation of myeloid leukemic cells by RA and 1,25(OH)2D3, which was probably mediated through their cognate nuclear receptors.44-46 Also, we previously found that the combination of a novel series of vitamin D3 analogs (20-epi vitamin D3 compounds) and 9-cis RA synergistically decreased proliferation and induced differentiation and apoptosis in APL cells.47 The mechanism by which RA enhances the effects of 1,25(OH)2D3remains to be clarified. RA may enhance the transactivation capacity of VDR by receptor heterodimerization of RAR/VDR or RXR/VDR. This heterodimerization may lead to efficient transactivation of cdk inhibitors. Moreover, the role of the APL-specific PML/RARα fusion protein in these processes should be explored.

In summary, 1,25(OH)2D3 can inhibit growth in the G1 phase of the cell cycle and induce differentiation of UF-1 RA-resistant APL cells. These effects are associated with an increased expression of several cdk inhibitors. Furthermore, the combination of RA and 1,25(OH)2D3 cooperatively enhances the expression of cdk inhibitors, G0/G1 cell cycle arrest, and differentiation of UF-1 cells.

Supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Science, and Culture of Japan, the National Grant-in-Aid for the Establishment of a High-Tech Research Center in a Private University and the Keio University Special Grants as well as grants from the National Institutes of Health, US Army, and Parker Hughes Fund.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to Masahiro Kizaki, MD, Division of Hematology, Keio University School of Medicine, 35 Shinanomachi, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 160-8582, Japan; e-mail:makizaki@mc.med.keio.ac.jp.

![Fig. 5. Expression of p21WAF1/CIP1 mRNA in HL-60 and NB4 cells, and p21WAF1/CIP1 and p27KIP1 transcripts in UF-1 cells. Cells were cultured with either 10−7 mol/L 1,25(OH)2D3 (A) or 10−7 mol/L all-trans RA (B) for 48 hours. Total RNA (15 μg per lane) was extracted and analyzed by Northern blot with [32P]-labeled p21WAF1/CIP1 or p27KIP1 cDNA probe. Bottom panel shows the ethidium bromide–stained formaldehyde gel before Northern blotting; the levels of 28S and 18S ribosomal RNA are comparable in each lane.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/93/7/10.1182_blood.v93.7.2225/5/m_blod40705005w.jpeg?Expires=1766613065&Signature=1vEwKdSGKp~kM0fgaGhc8PoNqhhm9p2g3Z970zkvaFTdTJgCW-mmObMWfkHUSjVXCRwGjlIm-X4Id8CfwAqZGYFaEhwliiU-lvtsr9~TS2XZMCvZCydxfwJCQeYbeaeErE~9VFX80oBSa79GqBibrFZVbewUH3~JM~sOmPkuqS6EFEDB5wUIxnBZaQNXPaP2GQ1JdMxB50-M8f9zQ58M7i6OAoPvJuWG4fvHQQCELw7iNMVkSZO0eKM6fJm9HuifO0BVlYq2m5Og5-KSeTGj2Lsrr7xcRQJngM5c4xYJAGSlQ5nFbYDAV5v8k0fmiB7DX~xwVt0V37K6QSzsIJ9I5A__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal