Abstract

The abnormal adherence of sickle red blood cells (SS RBC) to vascular endothelium may play an important role in vasoocclusion in sickle cell anemia. Thrombospondin (TSP), unusually large molecular weight forms of von Willebrand factor, and laminin are known to enhance adhesion of SS RBC. Also, these endothelial proteins bind to sulfated glycolipids and this binding is inhibited by anionic polysaccharides. Reversible sickling may expose normally cryptic membrane sulfatides that could mediate this adhesive interaction. In this study, we have investigated the effect of anionic polysaccharides, in the presence or absence of TSP, on SS RBC adhesion to the endothelium, using cultured human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) (for the adhesion assay) and the ex vivo mesocecum of the rat (for hemodynamic evaluation). The baseline adhesion (ie, without added TSP) of SS RBC to HUVEC was most effectively inhibited by high molecular weight dextran sulfate (HDS), whereas low molecular weight dextran sulfate (LDS) and the glycosaminoglycan chondroitin sulfate A (CSA) also had significant inhibitory effects. Heparin was mildly effective whereas other glycosaminoglycans (chondroitin sulfates B and C, heparan sulfate, and fucoidan) were ineffective. Similarly, HDS and CSA resulted in an improved hemodynamic behavior of SS RBC. Soluble TSP caused significant increases in SS RBC adhesion and in the peripheral resistance. Both HDS and CSA prevented TSP-enhanced adhesion and hemodynamic abnormalities. Thus, anionic polysaccharides can inhibit SS RBC-endothelium interaction in the presence or absence of soluble TSP. These agents may interact with RBC membrane component(s) and prevent TSP-mediated adhesion of SS RBC to the endothelium.

THE PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF SICKLE CELL anemia is due to a single amino acid substitution at the sixth position of the β chain ( β6, glu → val) of the hemoglobin (Hb) S molecule, which results in polymerization of HbS and sickling of red blood cells (RBC) under deoxygenated conditions. Although HbS polymerization is central to the pathophysiology of sickle cell disease, multiple factors (both primary and secondary) may be involved in the initiation of a vasoocclusive event. Among these factors, the abnormal adherence of sickle red blood cells (SS RBC) to the vascular endothelium may play an important role in vasoocclusion.1-7SS RBC adhesion to the endothelium occurs at venular wall shear rates8,9 and both ex vivo and in vivo studies have shown that postcapillary venules are the exclusive sites of SS RBC adherence in animal models.5,9 Under flow conditions, deformable light-density RBC (principally reticulocytes and discocytes) are most adherent5,8 and their increased adhesion in postcapillary venules of the ex vivo mesocecum preparation is followed by selective trapping of dense SS RBC that could result in vasoocclusion.5 10 Thus, adhesion of SS RBC in the microcirculation and the attendant hemodynamic abnormalities may have a potential role in the initiation of a vasoocclusive episode.

A number of mechanisms have been proposed to account for SS RBC-endothelium interactions. Factors such as RBC age and density, RBC shape, RBC membrane alterations, endothelial abnormalities, and plasma factors may influence these mechanisms. Although all SS RBC are potentially adherent,11,12 specific receptor-ligand interactions involve only a subset of sickle reticulocytes, ie, stress reticulocytes. α4β1 integrin and glycoprotein IV (CD36) are two such receptors that participate in sickle reticulocyte binding to the vascular endothelium via vascular adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) expressed on cytokine-stimulated endothelial cells and thrombospondin (TSP), respectively.13-17 In addition, unusually large molecular weight forms of endothelial von Willebrand factor (vWF) have been shown to increase overall SS RBC-endothelial interaction in both in vitro and ex vivo systems.18-20 However, SS RBC do not express the putative receptors for vWF, ie, GPIIb/IIIA or GPIb.13,21Other endothelial proteins that may participate in SS RBC-endothelium interactions are laminin and fibronectin.22-24

In both static and flow systems, SS RBC adhesion to the endothelium is enhanced by soluble TSP.16,17 Recent studies have shown that SS RBC also adhere avidly to immobilized TSP and that this interaction is not inhibited by antibodies to CD36, a TSP receptor, suggesting yet another mechanism by which SS RBC may bind to TSP.25,26 In one study,25 soluble TSP did not inhibit SS RBC adhesion to immobilized TSP, suggesting that epitopes responsible for mediating adhesion might be different for soluble versus immobilized TSP, and quite possibly for TSP expressed on the endothelium as well.

TSP-mediated adhesion may involve some of the same molecules that bind vWF. For example, both vWF and TSP can bind to αVβ3 integrin expressed on the endothelium.27,28 Also, vWF binds to immobilized TSP and blocks SS RBC binding sites on TSP, suggesting that SS RBC adhesion may be further influenced by relative concentrations of TSP and vWF in the vascular wall.29 Among the potential candidates on the RBC are sulfated glycolipids that are constituents of normal erythrocytes but are not normally exposed. In sickle-cell disease, reversible sickling and oxidative damage30 to the membrane could modify and/or abnormally expose these molecules to the surface. Both TSP and vWF bind to sulfated glycolipids and this binding is competitively inhibited by anionic polysaccharides in vitro.31-33 Recent studies have indicated that exposed sulfated glycolipids in the RBC membrane may mediate adhesion of SS RBC to immobilized TSP and that this interaction is inhibited by anionic polysaccharides.25 26 However, no evidence has been presented to show whether either direct or TSP-enhanced SS RBC adhesion to endothelium is affected by anionic polysaccharides. Also, the hemodynamic consequences of TSP-enhanced adhesion of SS RBC have not been previously investigated in a microvascular network.

The present studies were designed to resolve the following issues. Do anionic polysaccharides inhibit SS RBC adhesion to the vascular endothelium under shear-flow conditions and what is the hemodynamic impact of this inhibition? What are the hemodynamic consequences of TSP-enhanced adhesion? Can TSP-enhanced adhesion be inhibited by anionic polysaccharides? To resolve these issues, we have used two complementary dynamic assay systems. In one assay, SS RBC were infused into a parallel-plate flow chamber lined with human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC), and in the second assay, we evaluated their hemodynamic behavior in the ex vivo mesocecum vasculature of the rat.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

TSP purified from human platelets was generously provided by Dr J. Lawler (Harvard University, Cambridge, MA). All other reagents and anionic polysaccharides used in these studies were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO).

Preparation of cells.

Blood was drawn into heparinized tubes from normal adults (n = 3) and from sickle cell anemia patients (n = 9) who were not in crisis and had not received blood transfusion in the preceding 4 months. Blood samples from four sickle cell anemia patients were obtained at the Boston Comprehensive Sickle Cell Center and five patients were drawn at the Heredity Clinic of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY. Blood samples from three patients were shared between the two laboratories.

After removal of the buffy coat, blood was washed three times in Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS; 138 mmol/L NaCl, 5 mmol/L KCl, 0.3 mmol/L Na2HPO4, 0.3 mmol/L KH2PO4, 0.4 mmol/L MgSO4, 1.3 mmol/L CaCl2, 0.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 4 mmol NaHCO3, 5.6 mmol/L glucose plus 0.2% bovine serum albumin [BSA]; pH 7.4) and resuspended in HBSS/BSA for the adhesion assay involving HUVEC. For hemodynamic studies involving ex vivo mesocecum preparation of the rat, blood was washed three times in normal saline, once in bicarbonate Ringer-albumin solution (118 mmol/L NaCl, 5 mmol/L KCl, 2.5 mmol/L CaCl2, 0.64 mmol/L MgCl2, 27 mmol/L NaHCO3 plus 0.5% BSA, equilibrated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2; pH 7.4; osmolarity, 295 mOsm/Kg) and resuspended in Ringer-albumin solution.

Endothelial cells.

HUVEC were harvested from two to five umbilical cord veins, pooled, and grown in primary culture as previously described.34Cultures were serially passaged (1:3 split ratios) with M199-20% fetal calf serum supplemented with 50 to 100 μg/mL endothelial cell growth factor and 100 μg/mL porcine intestinal heparin in Costar tissue culture flasks (Cambridge, MA) coated with purified gelatin. Experiments were performed with second-passage HUVEC that were grown to confluence on fibronectin-coated LabTek slides (LabTek, Naperville, IL).

Erythrocyte adherence assay.

A parallel-plate flow chamber with an endothelial cell-coated slide as its base was used to assess the adhesion of RBC under defined fluid dynamic conditions. The flow chamber and the glass slide were held together by a vacuum maintained at the periphery of the slide forming a channel of parallel-plate geometry. The height of the flow channel, as determined by a silastic gasket, was 100 microns. After assembling the endothelial-coated slide in the flow chamber, RBC suspensions (Hct 1%) were drawn into the chamber from a reservoir maintained at 37°C in a water bath using a syringe pump (Model 956, Harvard Apparatus, South Natick, MA) at a controlled-flow rate to give a venular wall shear stress of 1 dyne/cm2. The flow chamber was mounted on an inverted-phase contrast microscope (DIAPHOT-TMD, Nikon, Garden City, NY) equipped with a CCD video camera (Model 72, Dage-MTI, Michigan City, IN). The microscope stage was maintained at 37°C by a thermostatic air bath (Model ASI-400, Nicholson Precision Instruments, Gaithersburg, MD). All of the experiments were recorded in real time on a 0.5 inch video cassette recorder (Model BV-1000, Mitsubishi, Cypress, CA) and displayed on a high-resolution monitor (Model PM-127, Ikegami, Maywood, NJ). A PC-based image processing system (Optimas, Bioscan, Edmunds, WA) was used for digitization of video recordings and for further image processing and analysis. For each adherence assay, the endothelial cell monolayer was rinsed for 2 minutes with HBSS followed by a 10-minute perfusion with the RBC suspension that had been untreated or incubated with a given anionic polysaccharide at 200 μg/mL for 30 minutes. In experiments involving the inhibition of TSP-enhanced adhesion, RBC suspensions were incubated sequentially with 200 μg/mL of a specific anionic polysaccharide for 30 minutes followed by a 30-minute incubation with 1 μg/mL of TSP. The treated suspensions (without any further manipulation) were then used for flow adhesion assay. The number of adherent erythrocytes remaining after a 10-minute rinse period were counted in a minimum of 24 fields and reported as the number of adherent RBC per mm2.

Hemodynamic studies using the ex vivo mesocecum preparation.

Hemodynamic studies were performed in the isolated, acutely denervated, artificially perfused rat mesocecum vasculature according to the method of Baez et al35 as modified for the study of erythrocytes.36 Arterial perfusion pressure (Pa) was rendered pulsatile with a peristaltic pump. Venous outflow pressure (Pv) was kept at 3.8 mm Hg, and the venous outflow rate (Fv) was monitored with a photoelectric drop counter and expressed as milliliters per minute. All perfusion experiments were performed at ambient air and at 37°C as described.6 During perfusion with Ringer’s at Pa of 60 mm Hg, a bolus of 0.3 mL red-cell suspensions (Hct 30%) was infused. Washed SS RBC suspensions were either untreated or incubated with a given polysaccharide (250 μg/mL) for 30 minutes. In experiments involving the inhibition of TSP-enhanced adhesion, SS RBC suspensions were incubated sequentially with 250 μg/mL of a specific anionic polysaccharide for 30 minutes followed by a 30-minute incubation with 2.5 μg/mL of TSP. The treated samples were then used for bolus infusion. Peripheral resistance units (PRU) were determined as described37 and expressed in mm Hg/mL/min/g. PRU = ΔP/Q, in which ΔP is the arteriovenous pressure difference and Q is the rate of venous outflow (mL/min) per gram of tissue weight. In each experiment, pressure-flow recovery time (Tpf) was determined after the bolus infusion of the samples. Tpf is defined as the time (seconds) required for Pa and Fv to return to their baseline levels after sample delivery and provides an estimate of total transit time through the mesocecum vasculature. Direct intravital microscopic observations and simultaneous video recording of the microcirculatory events were performed with an Olympus microscope (model BH-2; Olympus Corp, Lake Success, NJ) equipped with a television camera (Cohu 5000 series; Cohu, San Diego, CA) and a Sony U-matic video recorder (model VA5800; Sony, Teaneck, NJ).

Statistical analysis.

Paired t-test or unpaired Student’s t-test was applied to analyze data. The tests for hypothesis were performed using a Type-I error of 0.05 and were two-tailed. The statistical analyses were performed using Statgraphics Plus (version 3.1 ) program for Windows (Manugistics, Inc, Rockville, MD) and an IBM-compatible computer.

RESULTS

We evaluated the effect of anionic polysaccharides on SS RBC adhesion to the vascular endothelium and its hemodynamic consequences in the presence or absence of TSP, using two complementary dynamic assays. A parallel-plate flow chamber lined with HUVEC was used for the adhesion assay, whereas the hemodynamic behavior was evaluated in the ex vivo mesocecum vasculature.

Inhibition of SS RBC adhesion to HUVEC by anionic polysaccharides.

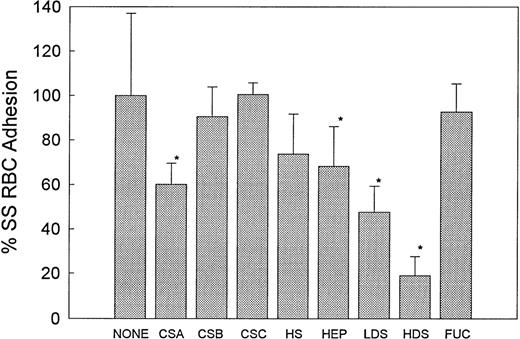

Anionic polysaccharides inhibit sickle erythrocyte binding to immobilized TSP.25 26 To determine if these compounds would also be effective inhibitors of sickle RBC adhesion to HUVEC, we screened a number of anionic polysaccharides in our adhesion assay. RBC suspensions in HBSS/BSA (hematocrit, 1%) were incubated with a given anionic polysaccharide at 200 μg/mL for 30 minutes before being perfused over HUVEC monolayers. The high molecular weight form of dextran sulfate (HDS, MW 500,000) (n = 9) was found to be the most effective inhibitor, blocking 78% of SS RBC adhesion to HUVEC (P < .0001) whereas the low molecular weight form of dextran sulfate (LDS, MW 5,000) (n = 7) inhibited 52% of SS RBC adhesion (Fig 1). The sulfated glycosaminoglycan chondroitin sulfate A (CSA) (n = 6) inhibited 40% of SS RBC adhesion to HUVEC (P < .001), whereas chondroitin sulfate B (CSB or dermatan sulfate) (n = 6) and chondroitin sulfate C (CSC) (n = 4) had no significant effect on adhesion (Fig 1). CSB and CSC differ from CSA in the substitution of iduronic acid for glucuronic acid, and in the position of sulfation of N-acetyl-β-galactosamine, respectively. Heparin (n = 6) resulted in a mild 30% inhibition of SS RBC adhesion, whereas the related glycosaminoglycan heparan sulfate (HS) (n = 3) was not effective. Fucoidan (n = 7) was also an ineffective inhibitor of RBC adhesion.

The effect of anionic polysaccharides on SS RBC adhesion to HUVEC. RBC suspensions were untreated (None, n = 10) or treated with 200 μg/mL of the indicated anionic polysaccharide for 30 minutes before being perfused through an endothelialized flow chamber at 1 dyne/cm2. Adherent RBC per mm2 were counted and reported as percent adhesion as compared with the control values that were normalized to 100%. Percent adhesion is depicted as the mean ± SD. CSA (n = 6) (40% inhibition, *P < .001), HDS (n = 9) (78% inhibition, *P < .0001), and LDS (n = 7) (52% inhibition, *P < .0001) were most effective in inhibiting adhesion. Heparin (n = 6) (26% inhibition, P < .002) was mildly effective, whereas CSB (n = 6), CSC (n = 4), HS (n = 3), and FUC (n = 7) were not effective inhibitors (pairedt-test).

The effect of anionic polysaccharides on SS RBC adhesion to HUVEC. RBC suspensions were untreated (None, n = 10) or treated with 200 μg/mL of the indicated anionic polysaccharide for 30 minutes before being perfused through an endothelialized flow chamber at 1 dyne/cm2. Adherent RBC per mm2 were counted and reported as percent adhesion as compared with the control values that were normalized to 100%. Percent adhesion is depicted as the mean ± SD. CSA (n = 6) (40% inhibition, *P < .001), HDS (n = 9) (78% inhibition, *P < .0001), and LDS (n = 7) (52% inhibition, *P < .0001) were most effective in inhibiting adhesion. Heparin (n = 6) (26% inhibition, P < .002) was mildly effective, whereas CSB (n = 6), CSC (n = 4), HS (n = 3), and FUC (n = 7) were not effective inhibitors (pairedt-test).

The effect of anionic polysaccharides on the hemodynamic behavior of SS RBC.

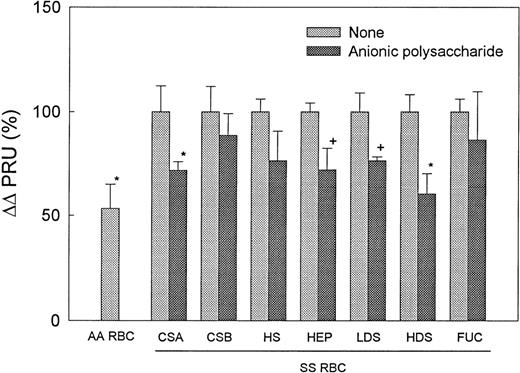

Next, we evaluated the hemodynamic behavior of SS RBC treated with selected anionic polysaccharides. In a series of experiments, washed SS RBC (Hct 30) were incubated with a given AP (250 μg/mL) and their hemodynamic behavior was compared with untreated SS RBC obtained from the same patient. A bolus of SS RBC (treated or untreated) was infused into the isolated mesocecum vasculature during perfusion with Ringer-albumin solution at an arterial pressure (Pa) of 60 mm Hg. In experiments (n = 13) in which hemodynamic behavior of human normal (AA) RBC was compared with SS RBC, the resulting PRU for SS RBC was almost twofold greater than that for AA RBC (%PRU: AA RBC, 20.0 ± 4.3; SS RBC, 38.7 ± 10.1; P< .0001, pairedt-test) (Fig 1). This increase in PRU for SS RBC was accompanied by a significantly prolonged pressure-flow recovery time (Tpf, sec; AA RBC, 40.4 ± 15.3; SS RBC, 81.5 ± 17.5,P<.0001, paired t-test). Both higher PRU and a delayed Tpf reflect abnormal rheological and adhesive properties of oxygenated SS cells as described earlier.5

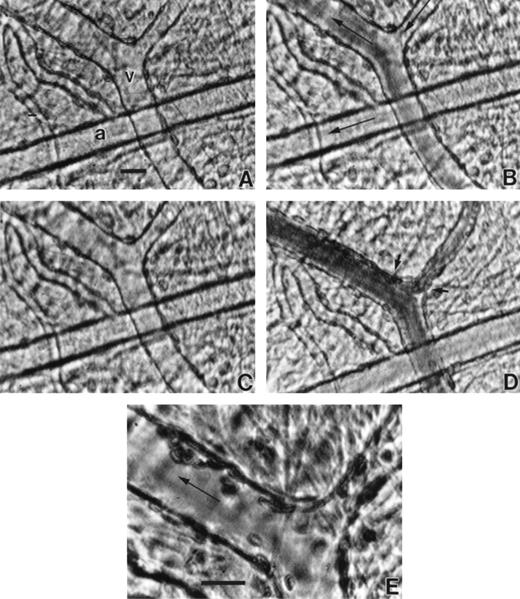

Table 1 gives percent PRU increases for untreated control and anionic polysaccharide-treated SS RBC over the Ringer baseline for each experimental group. Figure 2 depicts the relative differences in PRU (ΔΔ PRU, %) between untreated and treated SS RBC in each group after the values for untreated SS RBC are normalized to 100%. Of the various anionic polysaccharides tested, HDS was again the most effective, resulting in ∼40% decrease in PRU (n = 6) (P < .001) (Fig 2) and accompanied by a significant decrease in Tpf (P < .02) compared with untreated SS cells (Table 1). Direct microscopic observations showed almost no adherent cells in the mesocecum venules whereas infusion of untreated cells always resulted in variable degrees of adhesion in postcapillary venules (Fig 3) and occasionally produced postcapillary blockage. The PRU for HDS-treated SS RBC was only slightly higher compared with AA RBC (Fig 2). CSA (n = 5), heparin (n = 4), and LDS (n = 3) also caused significant decreases in PRU (P< .05 to .01), although to a lesser extent, ie, 28%, 28.3%, and ∼23.3%, respectively, and each resulted in a decreased Tpf (P < .02) (Fig 2, Table 1). As noted in the flow chamber, CSB (n = 3), HS (n = 4), and fucoidan (n = 3) did not have any significant effect on either PRU or Tpf in the mesocecal vasculature.

The Effect of Anionic Polysaccharides on Hemodynamic Behavior of SS RBC in the Ex Vivo Mesocecum Vasculature

| Experimental Group . | Treatment . | n . | ΔPRU (% increase) . | ΔΔPRU . | Tpf (sec) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | i. None | 5 | 35.7 ± 12.4 | 100.0 ± 12.4 | 68.0 ± 16.0 |

| ii. CSA | 5 | 25.5 ± 8.3* | 72.0 ± 4.2 | 54.0 ± 12.4‡ | |

| 2. | i. None | 3 | 39.8 ± 12.1 | 100.0 ± 12.1 | 85.0 ± 5.0 |

| ii. CSB | 3 | 35.9 ± 14.3 | 88.9 ± 10.3 | 80.0 ± 10.0 | |

| 3. | i. None | 4 | 25.0 ± 4.3 | 100 ± 4.3 | 52.5 ± 6.5 |

| ii. Heparin | 4 | 17.0 ± 1.7† | 72.3 ± 10.4 | 44.5 ± 4.2 | |

| 4. | i. None | 4 | 37.7 ± 10.6 | 100 ± 10.6 | 86.0 ± 24.6 |

| ii. HS | 4 | 28.5 ± 7.9† | 76.7 ± 14.0 | 68.0 ± 25.6‡ | |

| 5. | i. None | 3 | 35.4 ± 9.1 | 100.0 ± 9.1 | 95.0 ± 13.2 |

| ii. LDS | 3 | 27.0 ± 6.7† | 76.7 ± 1.8 | 61.7 ± 7.6‡ | |

| 6. | i. None | 6 | 37.7 ± 8.3 | 100.0 ± 8.3 | 97.5 ± 16.7 |

| ii. HDS | 6 | 23.0 ± 7.7* | 60.5 ± 10.0 | 65.8 ± 22.0‡ | |

| 7. | i. None | 3 | 29.7 ± 6.2 | 100 ± 6.2 | 68.3 ± 27.5 |

| ii. Fucoidan | 3 | 25.4 ± 6.5 | 86.7 ± 23 | 61.7 ± 7.6 |

| Experimental Group . | Treatment . | n . | ΔPRU (% increase) . | ΔΔPRU . | Tpf (sec) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | i. None | 5 | 35.7 ± 12.4 | 100.0 ± 12.4 | 68.0 ± 16.0 |

| ii. CSA | 5 | 25.5 ± 8.3* | 72.0 ± 4.2 | 54.0 ± 12.4‡ | |

| 2. | i. None | 3 | 39.8 ± 12.1 | 100.0 ± 12.1 | 85.0 ± 5.0 |

| ii. CSB | 3 | 35.9 ± 14.3 | 88.9 ± 10.3 | 80.0 ± 10.0 | |

| 3. | i. None | 4 | 25.0 ± 4.3 | 100 ± 4.3 | 52.5 ± 6.5 |

| ii. Heparin | 4 | 17.0 ± 1.7† | 72.3 ± 10.4 | 44.5 ± 4.2 | |

| 4. | i. None | 4 | 37.7 ± 10.6 | 100 ± 10.6 | 86.0 ± 24.6 |

| ii. HS | 4 | 28.5 ± 7.9† | 76.7 ± 14.0 | 68.0 ± 25.6‡ | |

| 5. | i. None | 3 | 35.4 ± 9.1 | 100.0 ± 9.1 | 95.0 ± 13.2 |

| ii. LDS | 3 | 27.0 ± 6.7† | 76.7 ± 1.8 | 61.7 ± 7.6‡ | |

| 6. | i. None | 6 | 37.7 ± 8.3 | 100.0 ± 8.3 | 97.5 ± 16.7 |

| ii. HDS | 6 | 23.0 ± 7.7* | 60.5 ± 10.0 | 65.8 ± 22.0‡ | |

| 7. | i. None | 3 | 29.7 ± 6.2 | 100 ± 6.2 | 68.3 ± 27.5 |

| ii. Fucoidan | 3 | 25.4 ± 6.5 | 86.7 ± 23 | 61.7 ± 7.6 |

The values are mean ± SD. ΔPRU represents percent increase in PRU following infusion of RBC compared with preinfusion PRU; ΔΔPRU represents percent changes after control values are normalized to 100%; Tpf, pressure-flow recovery time to the baseline level. In these experiments, SS RBC were either untreated or incubated with a given anionic polysaccharide (250 μg/ml).

Abbreviations: CSA and CSB, chondroitin sulfates A and B; LDS, low molecular weight dextran sulfate; HDS, high molecular weight dextran sulfate.

P < .01-.001 and

P < .05 (paired t-test) compared with control (None) ΔPRU.

P < .02 (paired t-test) compared with control Tpf.

The effect of anionic polysaccharides on the hemodynamic behavior of SS RBC in the ex vivo mesocecum vasculature. ▵▵PRU represents percent changes after untreated (none) SS control values were normalized to 100%. ▵▵PRU for AA RBC is ∼50% lower than for control SS cells. CSA (n=5), heparin (n=4), HDS (n=6), and LDS (n=3) resulted in significant decreases in PRU, ie, 28% (*P < .01), ∼27.7% (#P < .05), ∼40% (P < .001) and ∼23% (+P < .05), respectively (paired t-test). CSB (n = 3) and HS (n = 4) did not have any significant effect on PRU.

The effect of anionic polysaccharides on the hemodynamic behavior of SS RBC in the ex vivo mesocecum vasculature. ▵▵PRU represents percent changes after untreated (none) SS control values were normalized to 100%. ▵▵PRU for AA RBC is ∼50% lower than for control SS cells. CSA (n=5), heparin (n=4), HDS (n=6), and LDS (n=3) resulted in significant decreases in PRU, ie, 28% (*P < .01), ∼27.7% (#P < .05), ∼40% (P < .001) and ∼23% (+P < .05), respectively (paired t-test). CSB (n = 3) and HS (n = 4) did not have any significant effect on PRU.

The inhibitory effect of HDS on SS RBC adhesion in the mesocecum microvasculature. (A) Vessels show clear lumen during perfusion with Ringer-albumin (a, arteriole; v, venule). Bolus infusion of HDS-treated SS RBC results in rapid flow of these cells (B) with no resulting adhesion after the passage of the bolus (C). When untreated SS RBC are infused (D), their passage is accompanied by a variable extent of adhesion in venular segments depicted by small arrows. (E) Higher magnification of the area indicated by small arrows in D shows adhesion of SS RBC. The large arrows indicate the flow direction. Bars = 30 μm.

The inhibitory effect of HDS on SS RBC adhesion in the mesocecum microvasculature. (A) Vessels show clear lumen during perfusion with Ringer-albumin (a, arteriole; v, venule). Bolus infusion of HDS-treated SS RBC results in rapid flow of these cells (B) with no resulting adhesion after the passage of the bolus (C). When untreated SS RBC are infused (D), their passage is accompanied by a variable extent of adhesion in venular segments depicted by small arrows. (E) Higher magnification of the area indicated by small arrows in D shows adhesion of SS RBC. The large arrows indicate the flow direction. Bars = 30 μm.

Thrombospondin-enhanced adhesion of SS RBC to HUVEC and its prevention by anionic polysaccharides.

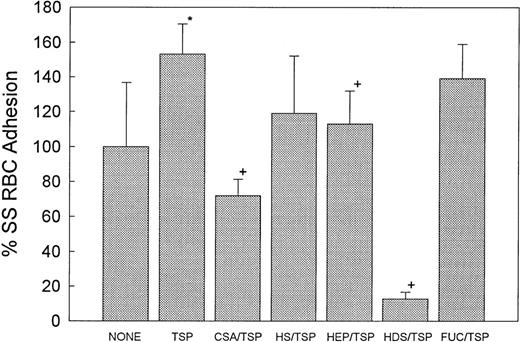

We next investigated whether TSP-enhanced adhesion of SS RBC could be prevented by anionic polysaccharides. In these experiments, SS RBC were treated with TSP (1 μg/mL) alone or incubated sequentially with a given anionic polysaccharide (CSA, HS, heparin, or HDS) at 200 μg/mL for 30 minutes and then with TSP (1 μg/mL) for 30 minutes. TSP alone enhanced endothelial cell adhesion of SS RBC by ∼50% (P < .01) (Fig 4). The prior addition of either CSA or HDS caused a significant inhibition of adhesion of SS RBC (P < .03 to .05). The decrease (ie, ∼87% decrease relative to the untreated control) in adhesion observed with HDS was comparable to that observed with HDS in the absence of TSP. The presence of CSA was also inhibitory. Adhesion showed 28% decrease compared with untreated cells (Fig 4) whereas CSA in the absence of TSP resulted in a greater inhibition (ie, ∼40%) of adhesion (Fig 2). Thus, sequential treatment of SS RBC with CSA and TSP resulted in less-effective inhibition of adhesion. Sequential treatment of SS RBC with heparin and TSP (n = 4) caused a significant reduction in adhesion compared with TSP-enhanced adhesion (P < .05), but the resulting adhesion was still somewhat higher as compared with untreated SS RBC (Fig 4). Pretreatment of SS RBC with HS (n = 3) or fucoidan (n = 5) had no effect on TSP-enhanced adhesion.

Prevention of TSP-enhanced adhesion of SS RBC to HUVEC by CSA and HDS. RBC suspensions were untreated (control, n = 4), incubated with 1 μg/mL of TSP (n = 3), or sequentially incubated with 200 μg/mL of a given anionic polysaccharide for 30 minutes and then with 1 μg/mL of TSP for 30 minutes. SS RBC adhesion was evaluated as described in Fig 2. At 1 μg/mL, TSP enhanced SS RBC adhesion by ∼50% compared with untreated (None) controls (*P< .01). This enhanced adhesion was prevented by pretreatment with HDS (n = 3) or CSA (n = 3) before TSP (+P < .05 to .03, compared with TSP) (pairedt-test). Heparin (n = 3) had a moderate effect (P < .05, compared with TSP) whereas HS (n = 3) and fucoidan (n = 5) had no effect.

Prevention of TSP-enhanced adhesion of SS RBC to HUVEC by CSA and HDS. RBC suspensions were untreated (control, n = 4), incubated with 1 μg/mL of TSP (n = 3), or sequentially incubated with 200 μg/mL of a given anionic polysaccharide for 30 minutes and then with 1 μg/mL of TSP for 30 minutes. SS RBC adhesion was evaluated as described in Fig 2. At 1 μg/mL, TSP enhanced SS RBC adhesion by ∼50% compared with untreated (None) controls (*P< .01). This enhanced adhesion was prevented by pretreatment with HDS (n = 3) or CSA (n = 3) before TSP (+P < .05 to .03, compared with TSP) (pairedt-test). Heparin (n = 3) had a moderate effect (P < .05, compared with TSP) whereas HS (n = 3) and fucoidan (n = 5) had no effect.

TSP-induced hemodynamic abnormalities are prevented by CSA and HDS.

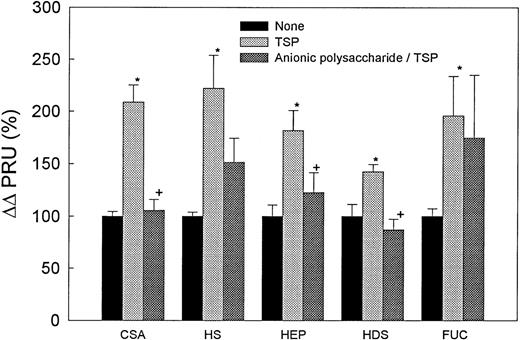

Because TSP caused a significant increase in adhesion of SS RBC to HUVEC that was abrogated by the presence of HDS and CSA, we evaluated the effect of a similar sequential treatment on the hemodynamic behavior of these cells in the mesocecum vasculature. Figure 5 depicts the results of five sets of experiments designed to evaluate the effect of TSP (2.5 μg/mL) alone and of sequential treatment with a given anionic polysaccharide (CSA, HS, heparin, HDS, and fucoidan, each 250 μg/mL) and TSP (2.5 μg/mL). In each group, incubation of SS RBC with TSP invariably caused a significant increase in PRU (P < .05 to .02) (Fig 5A-E), as well as in Tpf (P < .05) (Table 2) compared with untreated cells. These changes reflected an increase in SS RBC adhesion accompanied by modest postcapillary blockage. Adhesion was confined to venules and was characterized by frequent cluster formation of adherent SS RBC in the affected venules (Fig 6). The presence of CSA caused significant decreases in both PRU (P < .01) and Tpf (P < .05) (Table 2, Fig 5) compared with TSP-treated SS RBC; the resulting PRU was not significantly different from that observed with untreated cells. The presence of HS (n = 4) or fucoidan (n = 3) had no significant effect on PRU or Tpf as compared with TSP-treated SS RBC (Table 2, Fig 5). Sequential treatment with heparin and TSP (n = 5) caused a moderate decrease in PRU and Tpf (P < .5) as compared with that for TSP-treated SS RBC (Table2, Fig 5), although the resulting PRU was still higher than that for untreated cells. The presence of HDS resulted in maximal decreases in both PRU and Tpf as compared with TSP-treated SS RBC (P < .01) (Table 2, Fig 5).

TSP-induced hemodynamic abnormalities in the ex vivo mesocecum are prevented by anionic polysaccharides. In five sets of experiments, a bolus of SS RBC that had been preincubated with TSP alone at 2.5 μg/mL or preincubated sequentially with CSA, HS, heparin, HDS, or fucoidan at 250 μg/mL followed by TSP at 2.5 μg/mL was infused into the mesocecum vasculature. In each set of experiments, treatment solely with TSP resulted in a significant increase in PRU (*P < .05 to .02, paired t-test) compared with untreated RBC. Pretreatment with CSA (n = 3), heparin (n = 5), or HDS (n = 4) caused a significant decrease in PRU compared with TSP alone (+P < .01, < .05, and < .01, respectively, paired t-test). HS (n = 4) and fucoidan (n = 3) had no significant effect.

TSP-induced hemodynamic abnormalities in the ex vivo mesocecum are prevented by anionic polysaccharides. In five sets of experiments, a bolus of SS RBC that had been preincubated with TSP alone at 2.5 μg/mL or preincubated sequentially with CSA, HS, heparin, HDS, or fucoidan at 250 μg/mL followed by TSP at 2.5 μg/mL was infused into the mesocecum vasculature. In each set of experiments, treatment solely with TSP resulted in a significant increase in PRU (*P < .05 to .02, paired t-test) compared with untreated RBC. Pretreatment with CSA (n = 3), heparin (n = 5), or HDS (n = 4) caused a significant decrease in PRU compared with TSP alone (+P < .01, < .05, and < .01, respectively, paired t-test). HS (n = 4) and fucoidan (n = 3) had no significant effect.

Hemodynamic Behavior of SS RBC in the Ex Vivo Mesocecum Vasculature: Protective Effect of Anionic Polysaccharides on TSP-Enhanced Peripheral Resistance (PRU) and Pressure-Flow Recovery Times (Tpf)

| Experimental Group . | Treatment . | n . | ΔPRU (% increase) . | ΔΔPRU . | Tpf (sec) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | i. None | 3 | 24.8 ± 5.6 | 100.0 ± 5.6 | 73.3 ± 5.8 |

| ii. TSP | 3 | 51.7 ± 9.9* | 208.5 ± 16.7 | 113.3 ± 7.6* | |

| iii. CSA/TSP | 3 | 26.2 ± 5.02-153 | 105.8 ± 10.2 | 80.0 ± 5.0‡ | |

| 2 | i. None | 4 | 29.9 ± 3.9 | 100.0 ± 3.9 | 70.0 ± 17.8 |

| ii. TSP | 4 | 67.2 ± 16.82-153 | 222.0 ± 32 | 97.5 ± 12.6* | |

| iii. HS/TSP | 4 | 53.7 ± 21.8 | 151.3 ± 22.9 | 87.5 ± 11.9 | |

| 3 | i. None | 5 | 32.8 ± 11.0 | 100.0 ± 11.0 | 80.0 ± 26.5 |

| ii. TSP | 5 | 61.1 ± 20.5* | 181.8 ± 19.1 | 107 ± 32.1† | |

| iii. Heparin/TSP | 5 | 40.6 ± 16.1‡ | 122.5 ± 19.3 | 84.0 ± 24.6‡ | |

| 4 | i. None | 4 | 30.2 ± 11.3 | 100.0 ± 11.3 | 80.0 ± 16.3 |

| ii. TSP | 4 | 42.4 ± 17.8* | 142.7 ± 6.7 | 106.7 ± 22.6* | |

| iii. HDS/TSP | 4 | 25.9 ± 11.52-153 | 87.2 ± 10.2 | 82.5 ± 27.52-153 | |

| 5 | i. None | 3 | 31.1 ± 7.3 | 100.0 ± 7.3 | 71.7 ± 7.6 |

| ii. TSP | 3 | 59.7 ± 13.6* | 195.6 ± 38.1 | 168.3 ± 7.6† | |

| iii. FUC/TSP | 3 | 51.4 ± 6.9 | 174.6 ± 60.4 | 105.0 ± 26.0 |

| Experimental Group . | Treatment . | n . | ΔPRU (% increase) . | ΔΔPRU . | Tpf (sec) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | i. None | 3 | 24.8 ± 5.6 | 100.0 ± 5.6 | 73.3 ± 5.8 |

| ii. TSP | 3 | 51.7 ± 9.9* | 208.5 ± 16.7 | 113.3 ± 7.6* | |

| iii. CSA/TSP | 3 | 26.2 ± 5.02-153 | 105.8 ± 10.2 | 80.0 ± 5.0‡ | |

| 2 | i. None | 4 | 29.9 ± 3.9 | 100.0 ± 3.9 | 70.0 ± 17.8 |

| ii. TSP | 4 | 67.2 ± 16.82-153 | 222.0 ± 32 | 97.5 ± 12.6* | |

| iii. HS/TSP | 4 | 53.7 ± 21.8 | 151.3 ± 22.9 | 87.5 ± 11.9 | |

| 3 | i. None | 5 | 32.8 ± 11.0 | 100.0 ± 11.0 | 80.0 ± 26.5 |

| ii. TSP | 5 | 61.1 ± 20.5* | 181.8 ± 19.1 | 107 ± 32.1† | |

| iii. Heparin/TSP | 5 | 40.6 ± 16.1‡ | 122.5 ± 19.3 | 84.0 ± 24.6‡ | |

| 4 | i. None | 4 | 30.2 ± 11.3 | 100.0 ± 11.3 | 80.0 ± 16.3 |

| ii. TSP | 4 | 42.4 ± 17.8* | 142.7 ± 6.7 | 106.7 ± 22.6* | |

| iii. HDS/TSP | 4 | 25.9 ± 11.52-153 | 87.2 ± 10.2 | 82.5 ± 27.52-153 | |

| 5 | i. None | 3 | 31.1 ± 7.3 | 100.0 ± 7.3 | 71.7 ± 7.6 |

| ii. TSP | 3 | 59.7 ± 13.6* | 195.6 ± 38.1 | 168.3 ± 7.6† | |

| iii. FUC/TSP | 3 | 51.4 ± 6.9 | 174.6 ± 60.4 | 105.0 ± 26.0 |

The values are mean ± SD. ΔPRU represents percent increase in PRU following infusion of RBC compared with pre-infusion PRU for the preparation; ΔΔPRU represents percent changes after control values are normalized to 100%; Tpf, pressure-flow recovery time to the baseline level. In these experiments, SS RBC were either untreated, incubated with TSP (2.5 μg/ml) or treated sequentially with given anionic polysaccharide (250 μg/ml) and TSP (2.5 μg/ml) as described in Materials and Methods.

P < .05-.02 and

P < .01 (paired t-test) compared with control (None).

P < .05 and

P < .01 (paired t-test) compared with TSP.

Videomicrographs of TSP-enhanced adhesion of SS RBC in the ex vivo mesocecum venules. (A) Adhesion (small arrow) was confined to venules and (B) was characterized by frequent cluster formation of adherent SS RBC (small arrows) in the affected venules. The large arrow in each case indicates flow direction. Bar in A = 50 μm and bar in B = 20 μm.

Videomicrographs of TSP-enhanced adhesion of SS RBC in the ex vivo mesocecum venules. (A) Adhesion (small arrow) was confined to venules and (B) was characterized by frequent cluster formation of adherent SS RBC (small arrows) in the affected venules. The large arrow in each case indicates flow direction. Bar in A = 50 μm and bar in B = 20 μm.

DISCUSSION

The present study shows for the first time the efficacy of anionic polysaccharides to inhibit SS RBC interaction with vascular endothelium under dynamic flow conditions, both in the presence and absence of exogenous soluble TSP. In particular, the results show that the baseline adhesion of washed SS RBC to HUVEC under venular flow conditions is substantially inhibited in the presence of HDS, LDS, and CSA, whereas heparin is mildly effective and other sulfated polysaccharides (ie, CSB, CSC, and fucoidan) are ineffective. Similarly, when SS RBC are pretreated with HDS, CSA, and heparin and infused into the ex vivo mesocecum rat vasculature, a significant improvement in their hemodynamic behavior is observed as indicated by a decrease in the peripheral resistance. Furthermore, TSP-enhanced SS RBC adhesion to HUVEC, as well as attendant hemodynamic abnormalites in the mesocecum are most effectively ameliorated by pretreatment of SS RBC with HDS or CSA.

The increased adhesion of SS RBC to HUVEC in the presence of TSP is in agreement with previous reports that soluble TSP enhances adhesion of these cells to the microvascular endothelium under flow17and to HUVEC under static conditions.16 Importantly, TSP-enhanced adhesion of SS RBC results in hemodynamic abnormalities in the ex vivo mesocecum vasculature as is evident by an increase in the peripheral resistance and the attendant postcapillary blockage.

Of all the anionic polysaccharides tested in the absence or presence of TSP, HDS was most effective in both HUVEC and mesocecum assay systems followed by CSA and heparin. The present studies show that preincubation of SS RBC with HDS (MW 500 kD) results in maximal inhibition (78%) of baseline adhesion of these cells to HUVEC under flow. Similarly, HDS resulted in maximal inhibition (∼87%) of TSP-enhanced SS RBC adhesion to HUVEC at a concentration (ie, 200 μg/mL) lower than that used previously (500 to 1000 μg/mL) to inhibit SS RBC adherence to immobilized TSP.25,26 HDS was also the most effective in preventing the TSP-induced increase in the peripheral resistance in the mesocecum vasculature that is accompanied by increased adhesion and postcapillary blockage. CSA was the next most effective inhibitor of SS RBC adhesion to HUVEC, as well as in the mesocecum preparation. The related glycosaminoglycans, CSB and CSC, tested in the absence of TSP, were not effective inhibitors of SS RBC adhesion to HUVEC. HS, which has a charge density similar to the chondroitin sulfates, did not have any significant effect on SS RBC-endothelium interaction in both assay systems, as also reported by others using immobilized TSP.25,26 The related glycosaminoglycan heparin was mildly effective in the presence or absence of TSP. On the other hand, fucoidan was ineffective under similar conditions. Both heparin and fucoidan have higher charge densities than the chondroitin sulfates and molecular weights between those of the high and low molecular weight forms of DS.38

These results indicate that charge density of a given anionic polysaccharide may not be the only determining factor in the inhibition of adhesion, although the degree of sulfation and sulfation position may have a role. For example, HDS, the most effective inhibitor, is also heavily sulfated (ie, up to three sulfate groups per glucose molecule versus ∼2.5 sulfate groups per disaccharide for heparin and ∼1.0 sulfate group per disaccharide for chondroitin sulfates) and CSA differs from structurally similar CSC in the position of the sulfate group.39

Recent studies of Joneckis et al26 and Hillery et al25 have shown that binding of SS RBC to immobilized TSP is inhibited by anionic polysaccharides, although they did not examine effects on SS RBC interactions with endothelial cells. They also showed that antibodies to CD36, a TSP receptor, did not inhibit the binding of SS RBC to TSP. TSP/CD36-mediated interactions are likely to involve mainly CD36-expressing SS stress reticulocytes, and SS reticulocytes are also more adherent to TSP than other red cell populations of SS blood.16 Furthermore, the results obtained by Joneckis et al26 and Hillery et al25 have shown measurable adherence of mature SS RBC to immobilized TSP. These observations suggest that there is yet another mechanism involved in binding of SS RBC to TSP. In addition, previous studies have shown that all SS RBC, irrespective of density differences, are potentially adherent.11 12

Several previous in vitro studies have shown that sulfatides specifically bind certain adhesive proteins including TSP, vWF, and laminin.31-33,40 The presence of sulfated glycolipids, especially ceramide galactose-3-sulfate, has been detected in human and sheep erythrocytes. vWF, TSP, and laminin are similar in their ability to agglutinate gluteraldehyde-fixed erythrocytes.41 This function probably is the result of the capacity of these proteins to bind with sulfatide present in the RBC membrane. Of various sulfatides tested, ceramide galactose-3-sulfate has also been shown to be the best ligand for TSP, laminin, and vWF.32,33 Sickle erythrocytes are known to exhibit a variety of membrane abnormalities including phospholipid reorganization.42 Repeated sickling and the oxidative damage43 to the RBC membrane may affect phospholipid asymmetry, as well as expose normally cryptic sulfated glycolipids to the surface of the RBC membrane.

Consistent with the hypothesis that a sulfatide is involved in SS RBC interactions with TSP, Hillery et al25 isolated and characterized an acidic sulfatide from both AA and SS RBC and showed a strong affinity of this sulfatide for TSP. TSP binding to this acidic sulfatide was inhibited most effectively in the presence of HDS. In addition, HDS was found to be the most effective inhibitor of SS RBC adhesion to immobilized TSP. These results are consistent with findings by Roberts et al32 that TSP binds immobilized purified sulfated glycolipids and that this interaction is inhibited by fucoidan and HDS. In the present studies, however, fucoidan failed to inhibit SS RBC-endothelium interaction in both assay systems in the presence of soluble TSP. Also, fucoidan was found to be less effective than HDS or CSA in inhibiting SS RBC binding to immobilized TSP under conditions of flow.25 A greater inhibition by fucoidan of TSP binding to immobilized sulfatide32 33 may be possibly due to conformational differences in the immobilized form compared with that present in the lipid bilayer of intact RBC.

The inhibitory effect of anionic polysaccharides on the baseline adhesion of SS RBC observed in the absence of exogenous TSP could potentially involve blocking sites either on the red cell membrane or on endothelial adhesive proteins, such as TSP and vWF. Our results show that the presence of the anionic polysaccharides, HDS and CSA, effectively inhibits TSP-enhanced adhesion of SS RBC to vascular endothelium, indicating that in the presence of anionic polysaccharides, TSP, either soluble or bound, is unable to interact with SS RBC. Thus, in either case (ie, with or without exogenous TSP), anionic polysaccharides can inhibit SS RBC interaction with the vascular endothelium. In contrast, the addition of soluble TSP causes an increase in SS RBC adhesion in both assay systems, indicating that in the absence of anionic polysaccharides, TSP is able to bind to SS RBC. TSP, like vWF,44 may present a glycosaminoglycan-binding domain that is distinct from that interacting with sulfatides. Thus, we do not rule out the possibility that soluble TSP could potentially interact with anionic polysaccharides via its heparin-binding site, which would serve to also block TSP-mediated SS RBC adhesion to the vascular endothelium. Anionic polysaccharides may also inhibit the binding of TSP to other putative ligands on the endothelial cells that include αvβ3integrin and CD36.

The observed decline in baseline adhesion of SS RBC after pretreatment with anionic polysaccharides may also arise from decreased interactions of other endothelial adhesive molecules, including vWF and laminin. Recent studies have shown an increased adhesion of SS RBC to immobilized laminin and this interaction is partially inhibited by HDS.25 Both HUVEC and the ex vivo mesocecum preparation are capable of releasing vWF18,19 and may express laminin as well. The involvement of vWF is supported by previous observations that unusually large molecular weight forms of this protein enhance SS RBC adhesion to HUVEC18,20 and to postcapillary venules of the mesocecum.19

To conclude, the present study shows that SS RBC adhesion to the endothelium under shear flow conditions is selectively inhibited by certain anionic polysaccharides. The inhibitory potency of these anionic polysaccharides, in the absence or presence of TSP, was observed as follows: HDS>CSA>heparin. Furthermore, these studies show that, in general, the alterations in SS RBC adhesion to HUVEC parallel changes in the peripheral resistance in the rat mesocecum model. Importantly, the effectiveness of these anionic polysaccharides was found to be similar in both systems. Therapeutic strategies based on these, or similar, compounds that inhibit SS RBC adhesion to the vascular endothelium in vivo may prove useful in the therapy of patients with sickle cell disease.

Supported by NIH Grant No. HL45931 (D.K.K.) and by NIH Comprehensive Sickle Cell Centers at Boston, MA (HL15157; G.A.B. and B.M.E.) and Bronx, NY (HL 38655).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal