Abstract

The adherence of sickle erythrocytes to vascular endothelium has the capacity to initiate vasoocclusion. The known effects of thrombin on endothelial cell function and the increased activity of thrombin in sickle cell disease led us to examine the effect of thrombin on the adhesivity of cultured endothelial cells for sickle erythrocytes. In particular, we studied whether the effect of thrombin on interendothelial cell gap formation (ICGF) was involved in endothelial cell adhesivity for sickle erythrocytes. Those endothelial cell monolayers stimulated by thrombin to maximal levels of static sickle erythrocyte adherence also underwent striking cell contraction and enlargement of interendothelial cell gaps. Adhesivity also increased when gaps were induced with antilaminin antibodies or EDTA. Maximally adhesogenic thrombin conditions failed to increase adhesivity when gap formation was prevented by pretreatment of the monolayers with 8-bromo-cyclic adenosine monophosphate (bromo-cAMP) or glutaraldehyde, agents that respectively inhibit actin-myosin–dependent cell contraction or cross-link adjacent cells in the monolayer. The influence of these two agents on EDTA-enhanced adhesivity was linked to their ability to prevent gap formation. Glutaraldehyde prevented both increased adherence and gap formation; bromo-cAMP prevented neither. Interendothelial cell gap formation may contribute to vasoocclusion by facilitating sickle erythrocyte adherence.

© 1998 by The American Society of Hematology.

VASOOCCLUSION IN SICKLE cell anemia is unpredictable, often painful, and potentially fatal.1,2Thoughtful analyses of the polymerization of deoxyhemoglobin S and sickling of erythrocytes (red blood cells [RBC]) have delimited the basis of sickle cell disease.3-5 Despite their sophistication and detail, these interpretations have not identified determinants of sickle cell vasoocclusion that can be relied on to predict vasoocclusive events. In addition to the doctrine of sickling-induced vasoocclusion, there exists experimental evidence that vasoocclusion can be initiated by the adherence of sickle RBC (SS RBC) to vascular endothelium.6 Several RBC and endothelial cell (EC) receptors, subendothelial matrix adhesive proteins, and plasma ligands that contribute to the adherence have been elaborated.7,8 Further complexity is added to our understanding of this process by the action of a number of modifying influences on EC adhesivity8,9 and by uncertainty regarding whether sickle cell vasoocclusion occurs in the smallest capillaries or in larger vessels.10 Because of the direct and indirect evidence that sickle cell disease is associated with increased production and action of thrombin11-14 and of the numerous recognized effects of thrombin on EC function,15 we investigated the possible role of thrombin in potentiating the adherence of SS RBC to cultured human umbilical vein EC (HUVEC).

Thrombin affects the endothelium in ways that are predicted to influence adherence of SS RBC to vascular walls. Thrombin induces neutrophil (polymorphonuclear leukocyte [PMN]) adhesive molecules.16-18 In sickle cell disease, this occurs in the setting of commonly elevated leukocyte counts19 and PMN activated by SS RBC.20 The consequent adherence of PMN to EC is associated with a burst of reactive oxygen species and release of proteases,18,21 which loosen EC from basement membranes, causing interendothelial cell gap formation (ICGF) and endothelial barrier dysfunction.22 The altered EC adhesion properties22,23 and exposure of adhesive matrix proteins,24,25 inherent in this process, led us to the hypothesis that these inflammatory response elements26 also may be involved in thrombin-enhanced SS RBC adherence to vascular walls.

We studied the effects of thrombin on adherence of SS and nonsickle (AA) RBC to cultured EC, on the induction of cellular contraction and ICGF, and the possible interdependence of these effects. The integrity of confluent EC monolayers is the result of a dynamic equilibrium between constitutive low-level actin-myosin contraction and tethering forces provided by cell-cell adherin anchors and cell-matrix integrin moorings.27 Thrombin actively perturbs this equilibrium by triggering actin-myosin shortening22 by a rapid, reversible, receptor-mediated process.28 This active transduction of EC contraction and ICGF22 can be blocked by specific inhibition of signal transduction or contractile elements and by nonspecific prevention of EC contraction.29 ICGF can be engendered permissively by severing cell-cell and cell-matrix tethers, leaving basal actin-myosin tension unopposed.27 For instance, tethers can be disrupted by chelation of divalent cations or by interruption of EC-matrix associations using RGD peptides, antibodies directed against integrin-binding domains of matrix proteins,22 or antibodies against EC receptors for fibronectin (Fn) or vitronectin.30

To investigate the proposed linkage between EC adhesivity and gap formation, we analyzed the effects of thrombin, of agents that promote ICGF permissively, and of inhibitors of ICGF on both ICGF and EC adherence of SS RBC. Our findings suggest a contribution of ICGF to SS RBC adherence and vasoocclusion.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

Gelatin, heparin, thrombin, M199 medium, Fn from human plasma, bovine serum albumin (BSA), HEPES buffer, bromo-cAMP (8-bromo-cyclic adenosine monophosphate), IBMX (isobutyl-methylxanthine), and Evans Blue dye were from Sigma Chemicals Co (St Louis, MO). Hanks’ buffered saline solution, L-glutamine, 100 × penicillin/streptomycin, calcium/magnesium-free phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) were from the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) cell culture facility. Trypsin 0.025%/EDTA 0.01% and endothelial cell growth medium (EGM) were from Clonetics Corp (San Diego, CA). Dispase II and EC growth factor were from Boehringer Mannheim Corp (Indianapolis, IN). Fetal bovine serum was from HyClone Laboratories, Inc (Logan, UT). Serva electron microscopic grade glutaraldehyde was a 25% solution in water from Boehringer Ingelheim (Heidelberg, Germany). Polyclonal anti–von Willebrand factor (vWF) and polyclonal antilaminin were purchased from DAKO A/S (Glostrup, Denmark). Rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin was from Molecular Probes, Inc (Eugene, OR). Four-chambered culture slides were from NUNC (Naperville, IL). Biomeda Gel Mount was from Biomeda Corp (Foster City, CA), Vectashield mounting medium was from Vector Laboratories, Inc (Burlingame, CA), and Transwell multiple well culture plates with 3.0 μmol/L pore polycarbonate membranes were from Corning Costar Corp (Cambridge, MA).

Cell culture.

HUVEC cultures were obtained from anonymous umbilical cord donors at the San Francisco General Hospital Labor and Delivery Ward with approval from the UCSF Human Research Committee. HUVEC were isolated within 3 days of cord collection according to the method of Jaffe et al31 with the following modifications. Enzymatic digestion to free the HUVEC was for 10 minutes at 37°C with 0.15% dispase in M199 medium. Cells were grown at 37°C in 5% CO2/95% air in gelatin-coated flasks in M199 medium supplemented with 10% human serum pooled from normal male donors and 10% fetal bovine serum, 20 μg/mL EC growth factor, 100 μg/mL heparin, 2 mmol/L L-glutamine, 100 mg/mL penicillin/100 mg/mL streptomycin solution (G-10 medium). Cobblestone morphology and positive staining by an antibody to vWF identified the resulting culture as EC. At 85% confluence, the cells were subcultured to Fn-coated 4-chambered slides. The second to the fourth passages were used for adherence assays no later than 24 hours after HUVEC had reached confluence. For the photographic/morphometric analyses and some of the monolayer permeability studies, HUVEC were obtained from a commercial source (Clonetics) and grown in EGM.

Sickle cell and control blood.

Blood samples were drawn from homozygous sickle cell patients of the San Francisco General Hospital Hematology Clinic or from volunteer control subjects after obtaining informed consent, as approved by the UCSF Committee on Human Research. All subjects were in steady state condition, none had received blood transfusions within 4 months, and none were being treated with hydroxyurea.

Gravity adherence assays.

Our method of assaying static adherence of RBC to HUVEC monolayers was adapted from a published method.32 Heparinized blood from normal donors and sickle cell subjects was washed three times in PBS and once in Hanks’ buffered saline solution, 1% BSA, 50 mmol/L HEPES pH 7.4 (HAH), taking care to deplete the samples of leukocytes and platelets by removing the buffy coat with each wash, and RBC were suspended to 3.5% hematocrit in HAH containing 17% autologous platelet-free plasma from the heparinized blood sample. Confluent HUVEC monolayers were washed with HAH to remove traces of serum and treated with the following agents: thrombin at concentrations spanning 0.01 to 0.5 U/mL in HAH or thrombin-free HAH for 5 minutes; 0.5 mmol/L EDTA in calcium, magnesium-free PBS or EDTA-free calcium, magnesium-free PBS for 10 seconds; or 140 mg/L polyclonal antilaminin antibody in EGM or EGM alone for 1 hour. For studies of the influence of cell contraction or gap induction, after washing away traces of serum and medium, the monolayers were incubated at 37°C with 200 μmol/L bromo-cAMP and 200 μmol/L IBMX in EGM for 20 minutes or with 3% glutaraldehyde in PBS for 10 minutes. These reagents were washed away twice with HAH and gentle shaking for 5 minutes and the EC were then treated as above with thrombin or EDTA. Immediately after washing with HAH to remove traces of the above agents, the monolayers were covered with AA RBC or SS RBC suspensions and incubated at 37°C for 25 minutes. The wells were then filled completely with HAH, sealed with packing tape, and inverted at 37°C for 20 minutes. While still inverted, the well walls and gaskets of the slide chambers were removed. The slides were rinsed twice with HAH to remove nonadherent RBC, fixed in 3% glutaraldehyde, stained, and mounted. RBC adherence was monitored visually by microscopy at 100× magnification and quantified by counting RBC adherent to HUVEC monolayers in 16 fields marked by a grid (same random fields for each sample). The mean adherence and SEM for each sample (n = 16) was calculated and results were used to determine the reported means from at least four experiments, only when the standard error of mean (SEM) of each sample was less than 20% of the means. Results were analyzed by the Student’s t-test, with whichP < .05 was considered significant.

Distribution of RBC adherence to EC monolayers.

The distribution of SS RBC adherent to EC monolayers that had or had not been exposed to 0.1 U/mL thrombin was assessed in three representative static assays. An arbitrary number of adherent SS RBC were scored as “at the edges of EC” when they were on the subendothelium, but touching or overlapping at least one EC, RBC “in the gaps” had no physical contact with an EC, and RBC “on an EC” was completely on top of an EC and had no part of it touching the edge of the cell. Percent is of the total RBC counted on the EC monolayers.

Photomicrographs of HUVEC monolayers and morphometric analysis of ICGF.

HUVEC monolayers were grown to 95% confluence on 35 mm tissue culture plates then observed using a Nikon Diaphot Inverted Microscope (Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Cells were washed with PBS three times then treated for 5 minutes with concentrations of thrombin spanning 0.01 to 0.5 U/mL in HAH or with HAH alone. After 5 minutes, the monolayers again were washed three times with PBS, and EGM was added. At selected intervals before and after treatment, photomicrographs were taken using a Polaroid MicroCam with Polaroid 337 film (Polaroid Corporation, Cambridge, MA). To retain the same field for successive pictures, the microscope stage was immobilized. Photomicrographs were scanned using a UMAX 1200S scanner (UMAX Technologies, Inc, Fremont, CA) and cell areas measured using the Melanie gel analysis program (BioRad, Hercules, CA), whereby cells were detected as spots. Gap percentages were determined as:

Monolayer permeability assay.

The permeability of HUVEC monolayers to Evans Blue Albumin (EBA; 0.67 mg/mL Evans Blue dye, 4% bovine serum albumin, in G-10 medium), as a measure of ICGF, was determined using an adaptation of the method of the Garcia laboratory.33 HUVEC monolayers were grown on tissue culture-treated Transwells (Corning Costar) in 24-well microtiter plates. The upper Transwell and lower culture plate wells were filled with G-10 medium, 50 μL and 500 μL, respectively. Initially the medium was removed entirely from the Transwell and replaced by 50 μL EBA. At 10-minute intervals for 1 hour before treatment of the monolayer, the entire bottom well medium was removed for analysis by spectrophotometry and replaced with 500 μL fresh G-10. EBA in the Transwells also was replaced with 50 μL fresh EBA every 10 minutes. For treatment of the monolayers, the Transwells were washed three times with PBS then treated for 5 minutes with 0.1 U/mL thrombin in HAH or with HAH alone, after which the Transwells were again washed three times with PBS. The 0 time point for treatment samples was when the monolayers first were exposed to thrombin or HAH. After treatment, medium from the bottom well was collected for analysis and replaced at times 0, 5, 10, 20, and 40 minutes, and EBA was replaced in the Transwell at the same time intervals. All samples were diluted 1:1 in G-10 medium, and mean optical density (OD) (630 nm) values were derived from multiple identical experimental samples.

EBA standards were used to create a calibration curve of OD versus mg/mL of albumin. The diffusion of EBA from the luminal buffer in the Transwell to the abluminal buffer in the lower well was expressed as mg albumin/minute/cm2 of monolayer. Replicate samples, six for control and five for thrombin-treated, were taken at several 10-minute time points before and after treatment. The start of the 5-minute treatment was used as the 0 time point.

Immunofluorescence microscopy (IF).

HUVEC grown on Fn-coated 4-chambered slides were washed and treated with thrombin, EDTA, or HAH, with or without inhibitors of ICGF, as described above, and fixed in acetone for 5 seconds at −20°C. After washing in PBS/1% BSA, the cells were blocked in PBS/3% BSA for 1 hour at room temperature, and labeled in blocking solution with rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin (1:100 dilution) for 1 hour at room temperature. After the chamber walls and gaskets were removed, the slides were washed twice, mounted with coverslips, and photographed at 500× magnification with automatically adjusted shutter speeds using a Nikon epifluorescence microscope equipped with a Nikon UFX-35A camera.

RESULTS

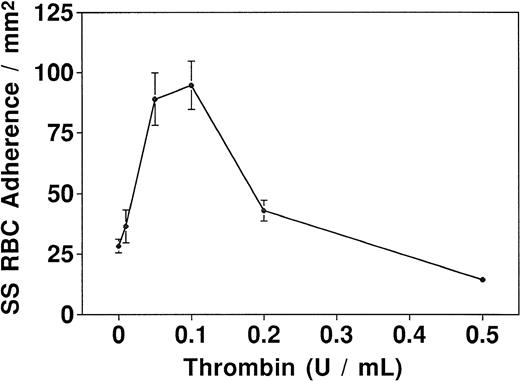

We assessed the effects of different thrombin concentrations by treating HUVEC with increasing concentrations from 0.01 to 0.5 NIH U/mL for 5 minutes and quantifying SS RBC adherence using a static assay. In four experiments, adherence increased in a dose-dependent manner, peaking at 0.1 U/mL, and decreased at higher concentrations to the levels of unstimulated control HUVEC (Fig1). This dose-response curve for SS RBC adherence is similar to a published curve for thrombin-induced ICGF, including curve shape, maximum concentration, and minimum exposure time.28Consistent with other studies of the effects of thrombin on primary HUVEC cultures, individual cultures varied considerably according to the monolayer age and cell density. Some cultures did not respond, and others were destroyed by usually effective concentrations and durations of exposure to thrombin. We alleviated this problem in part by using cultures within 24 hours of reaching “cobblestone” morphology. We chose as our working conditions of thrombin exposure those with maximal adhesogenic effect, 0.1 U/mL for 5 minutes. Our findings and conclusions pertain to those conditions.

Dose response curve for thrombin-induced adherence. Each point represents the mean number from four static assays of SS RBC adherent to 1 mm2 of HUVEC treated with thrombin concentrations ranging from 0 to 0.5 NIH U/mL.

Dose response curve for thrombin-induced adherence. Each point represents the mean number from four static assays of SS RBC adherent to 1 mm2 of HUVEC treated with thrombin concentrations ranging from 0 to 0.5 NIH U/mL.

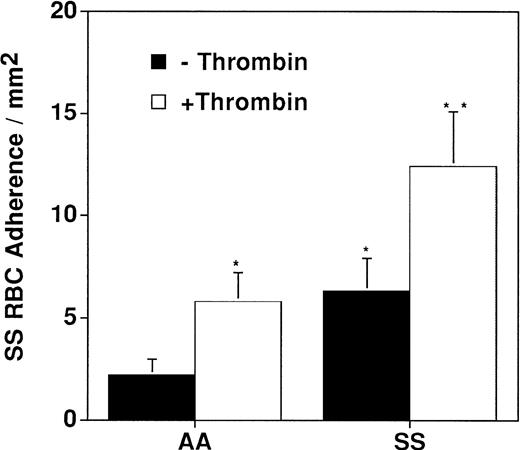

Adherence of SS RBC was compared with that of AA RBC (Fig 2). The number of AA RBC adherent to unstimulated HUVEC varied from 0.1 to 7.9 with a mean of 2.2 RBC/mm2 (n = 9). Adherence of SS RBC ranged from 1.2 to 17.9 with a mean of 6.3 RBC/mm2 (n = 9). The greater extent and variability of SS RBC adherence, compared with AA RBC, is comparable to the findings of others.9 A 5-minute treatment of HUVEC with 0.1 U/mL thrombin caused a significant increase in RBC adherence with both RBC populations. Mean values of adherence increased from 2.2 to 5.8 AA RBC/mm2 (n = 9) and from 6.3 to 12.4 SS RBC/mm2 (n = 9). Thrombin was found to influence EC adhesivity for both AA and SS RBC, but was quantitatively greater for the latter.

AA and SS RBC adherence to HUVEC that had been treated with thrombin or with control buffer. The mean ± SEM is shown (n = 9).

AA and SS RBC adherence to HUVEC that had been treated with thrombin or with control buffer. The mean ± SEM is shown (n = 9).

In our studies of adherence, it appeared that RBC adhered mainly to the edges of EC, which were separated from neighboring EC and almost never to areas of the endothelium that remained tightly adherent, a relationship we observed in both unperturbed monolayers and those in which ICGF had been induced by thrombin. To corroborate this finding, in three representative experiments, we determined the site of adherence of an arbitrary number of adherent SS RBC, 219 RBC on unperturbed monolayers and 308 RBC on thrombin-treated monolayers. As shown in Table 1, the distribution of adherent SS RBC to unperturbed or thrombin-treated monolayers was, respectively, 65% and 66% of SS to EC edges, 22% and 21% on top of EC, and 12% and 13% in the gaps with no contact to an EC. The persistence of the identical distribution pattern after thrombin treatment, in the context of a twofold overall increase in adherence, indicates commensurate increases at all three sites, EC edges, EC luminal surfaces, and exposed matrix.

Distribution of Adherent RBC to EC Monolayers Before and After Thrombin Treatment

| SS RBC Location . | No Thrombin . | With Thrombin . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of RBC . | % . | No. of RBC . | % . | |

| EC edges | 143 | 65 | 204 | 66 |

| EC luminal surface | 49 | 22 | 65 | 21 |

| Within gaps | 27 | 12 | 39 | 13 |

| Total | 219 | 100 | 308 | 100 |

| SS RBC Location . | No Thrombin . | With Thrombin . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of RBC . | % . | No. of RBC . | % . | |

| EC edges | 143 | 65 | 204 | 66 |

| EC luminal surface | 49 | 22 | 65 | 21 |

| Within gaps | 27 | 12 | 39 | 13 |

| Total | 219 | 100 | 308 | 100 |

Locations of an arbitrary number of adherent RBC on EC monolayers in three separate experiments were tabulated. These distributions reflect locations only, not quantitative differences in overall adherence. RBC adhered primarily to the sides of EC that were pulled apart, and the distribution did not change after thrombin treatment.

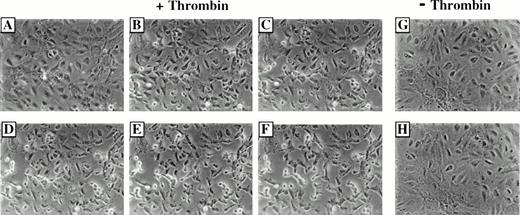

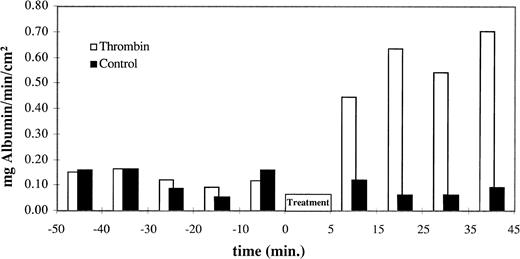

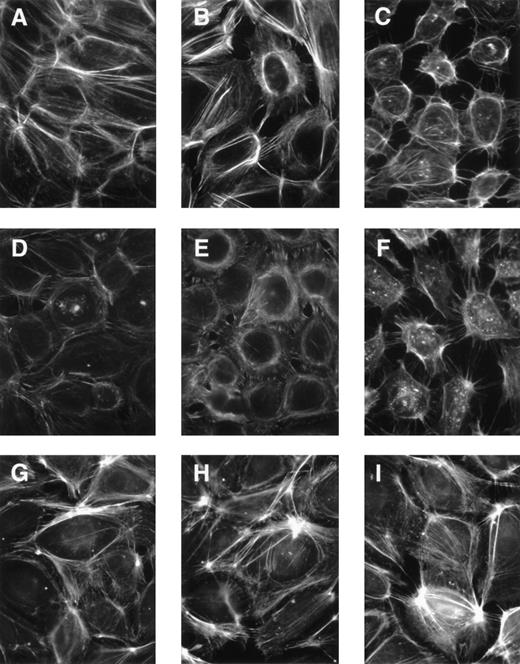

To confirm the effects of thrombin on EC contraction and ICGF that was apparent during the adherence assays, we used computerized morphometry and an assay of monolayer permeability to EBA. Serial photographs of the same microscopic field taken at 0, 2, 5, 10, 20, and 40 minutes after a 5-minute exposure to 0.1 U/mL thrombin showed a prompt and striking contraction of EC and ICGF (Fig 3A through F). In contrast, a 5-minute exposure to HAH alone resulted in neither EC contraction nor ICGF, as seen by comparing photographs taken before and 40 minutes after a 5-minute exposure to HAH alone (Fig 3G and H). Quantification of these observations by computerized morphometry using the Melanie gel analysis system (BioRad, Hercules, CA) to define the relative areas of gaps and cells in scans of the above photomicrographs demonstrated a prompt 14-fold increase in ICGF (Table 2). We also used this method to assess the influence of different thrombin concentrations on ICGF. We found that a degree of ICGF matching that observed with 0.1 U/mL thrombin was induced by 0.2 and 0.5 U/mL thrombin (data not shown), concentrations at which adherence was substantially diminished (Fig 1). Thrombin also induced a prompt increase in permeability of monolayers to EBA. Figure 4 shows that the same thrombin conditions resulted in a threefold increase in EBA permeability within 5 minutes, which persisted at approximately that level through the 40-minute period of measurement, and that there was no change induced by HAH alone. The permeability data presented are those of a single representative experiment, which was corroborated in two other studies. These visual, morphometric, and permeability data confirm that, in addition to its effect on EC adhesivity for AA and SS RBC, thrombin induced ICGF.

Photomicrographs of HUVEC monolayers before and at intervals after treatment with HAH buffer with or without 0.1 U/mL thrombin. (A) Nearly confluent monolayer before treatment with thrombin. (B through F) The same microscope field 2 minutes (B), 5 minutes (C), 10 minutes (D), 20 minutes (E), and 40 minutes (F) after a 5-minute exposure to thrombin. (G) Nearly confluent monolayer before treatment with HAH buffer. (H) The same microscope field as in (G) 40 minutes after a 5-minute exposure to HAH alone. The monolayer treated with thrombin (B through F) demonstrates a progressive and pronounced ICGF compared with the pretreatment monolayer (A). The monolayer exposed to HAH alone demonstrated no detectable ICGF after 40 minutes (G and H). Morphometric quantification of gap formation is tabulated in Table 2.

Photomicrographs of HUVEC monolayers before and at intervals after treatment with HAH buffer with or without 0.1 U/mL thrombin. (A) Nearly confluent monolayer before treatment with thrombin. (B through F) The same microscope field 2 minutes (B), 5 minutes (C), 10 minutes (D), 20 minutes (E), and 40 minutes (F) after a 5-minute exposure to thrombin. (G) Nearly confluent monolayer before treatment with HAH buffer. (H) The same microscope field as in (G) 40 minutes after a 5-minute exposure to HAH alone. The monolayer treated with thrombin (B through F) demonstrates a progressive and pronounced ICGF compared with the pretreatment monolayer (A). The monolayer exposed to HAH alone demonstrated no detectable ICGF after 40 minutes (G and H). Morphometric quantification of gap formation is tabulated in Table 2.

Morphometric Studies of Thrombin-Induced ICGF

| . | Time After 5 Min Treatment With 0.1 U/mL Thrombin in HAH . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PT* . | 5 sec . | 2 min . | 5 min . | 10 min . | 20 min . | 40 min . | |

| Total area | 7,638 | 7,545 | 7,584 | 7,638 | 7,578 | 7,612 | 7,621 |

| Cell area | 7,286 | 3,647 | 3,248 | 2,669 | 2,487 | 2,342 | 2,291 |

| Gaps† | 352 | 3,898 | 4,336 | 4,969 | 5,091 | 5,270 | 5,330 |

| % Gaps‡ | 4.6 | 51.7 | 57.2 | 65.1 | 67.2 | 69.2 | 69.9 |

| Fold gap inc1-153 | None | 10 | 11 | 13 | 14 | 14 | 14 |

| Time After 5 min Treatment With HAH | |||||||

| PT* | 40 min | ||||||

| Total area | 7,603 | 7,603 | |||||

| Cell area | 7,514 | 7,531 | |||||

| Gaps† | 89 | 72 | |||||

| % Gaps‡ | 1.2 | 0.9 | |||||

| Fold gap inc1-153 | None | 0 | |||||

| . | Time After 5 Min Treatment With 0.1 U/mL Thrombin in HAH . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PT* . | 5 sec . | 2 min . | 5 min . | 10 min . | 20 min . | 40 min . | |

| Total area | 7,638 | 7,545 | 7,584 | 7,638 | 7,578 | 7,612 | 7,621 |

| Cell area | 7,286 | 3,647 | 3,248 | 2,669 | 2,487 | 2,342 | 2,291 |

| Gaps† | 352 | 3,898 | 4,336 | 4,969 | 5,091 | 5,270 | 5,330 |

| % Gaps‡ | 4.6 | 51.7 | 57.2 | 65.1 | 67.2 | 69.2 | 69.9 |

| Fold gap inc1-153 | None | 10 | 11 | 13 | 14 | 14 | 14 |

| Time After 5 min Treatment With HAH | |||||||

| PT* | 40 min | ||||||

| Total area | 7,603 | 7,603 | |||||

| Cell area | 7,514 | 7,531 | |||||

| Gaps† | 89 | 72 | |||||

| % Gaps‡ | 1.2 | 0.9 | |||||

| Fold gap inc1-153 | None | 0 | |||||

*PT, prior to treatment.

Gaps = Total Area − Cell Area.

% Gaps = Gaps ÷ Total Area.

Fold gap inc = [% Gaps (at Time Point) − % Gaps (at PT)] ÷ % Gaps (at PT).

EBA permeability of HUVEC monolayers. The diffusion of EBA from the luminal buffer in the Transwell to the abluminal buffer in the lower well is shown as mg albumin/minute/cm2 monolayer from 60 minutes before until 40 minutes after exposure to 0.1 U/mL thrombin in HAH buffer (black bars) or to HAH alone (shaded bars). Samples were taken at several time points before and after treatment; the 0 time point is equivalent to the start of the 5-minute treatment. Thrombin exposure resulted in a rapid increase in monolayer permeability to EBA, which was sustained for the duration of these measurements.

EBA permeability of HUVEC monolayers. The diffusion of EBA from the luminal buffer in the Transwell to the abluminal buffer in the lower well is shown as mg albumin/minute/cm2 monolayer from 60 minutes before until 40 minutes after exposure to 0.1 U/mL thrombin in HAH buffer (black bars) or to HAH alone (shaded bars). Samples were taken at several time points before and after treatment; the 0 time point is equivalent to the start of the 5-minute treatment. Thrombin exposure resulted in a rapid increase in monolayer permeability to EBA, which was sustained for the duration of these measurements.

Based on the apparent association of increased adherence and ICGF, we tested the influence of nonspecific mechanisms of ICGF on RBC adherence. We treated EC monolayers briefly with a low concentration of EDTA to remove the divalent cations necessary for cell-matrix and cell-cell interactions or with an antilaminin polyclonal antibody to disrupt EC-matrix tethers. A 10-second exposure to 0.5 mmol/L EDTA caused the cells to separate slightly. After washing away traces of EDTA and monitoring visually by microscopy for initial cell rounding, the adherence assay was performed as usual in the presence of divalent cations. This treatment resulted in a significant (P < .05) increase in the mean adherence of SS RBC from 5.1 to 15.5 RBC/mm2 (n = 3). Exposure of EC to antilaminin antibody before the adherence assay also caused a significant (P < .05) increase in mean adherence (n = 3). The control adherence data to which treated data were compared were those from all of the experiments (n = 6). These results suggested that ICGF is associated with increased RBC adherence.

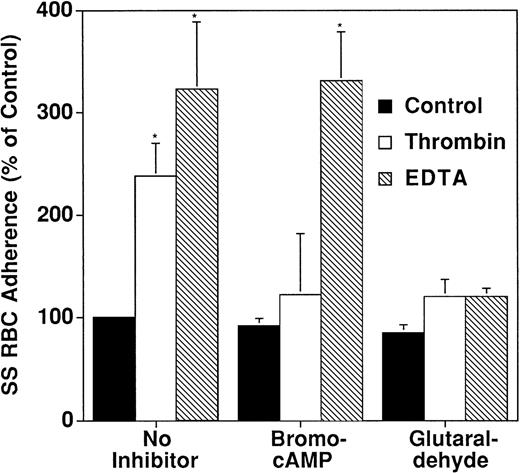

To test this association further, before treating with thrombin or EDTA, we preincubated EC with one of two different agents that prevent ICGF, bromo-cAMP or glutaraldehyde. Bromo-cAMP is a cAMP analog that inhibits cell contraction and protects EC barrier function,34 and glutaraldehyde is a cross-linking agent that fortifies cell-cell and cell-matrix tethers, in addition to other likely effects. Buffer treatment was used as a negative control, and EDTA was used as a positive control for ICGF. The cellular effects of these agonists and antagonists are shown in the composite IF photograph of rhodamine-labeled actin filaments (Fig5), which shows the effects of the various treatments on the endothelial cytoskeleton and monolayer integrity. Untreated cells (Fig5A) were closely adjacent with no intercellular gaps and had well-defined peripheral bands of actin stress fibers. Thrombin-treated HUVEC (Fig 5B) had large intercellular gaps, disrupted and reorganized stress fibers, and occasional actin fibers distributed across the gaps. EDTA-treated cells also had retracted to create intercellular gaps, had fewer defined actin fibers than the thrombin-treated cells, and remained attached by fine processes (Fig 5C). Pretreatment with bromo-cAMP plus the phosphodiesterase inhibitor IBMX caused no discernible changes in intercellular gaps or actin fibers (Fig 5D), prevented thrombin-elicited changes in actin stress fibers and ICGF (compare Fig 5E with 5B), but did not prevent the effect of EDTA on ICGF (compare Fig 5F with 5C). Pretreatment with the concentration of glutaraldehyde we used allowed minimal changes in actin stress fibers, but no increased separation of EC (Fig 5G). Despite slight further stress fiber condensation, glutaraldehyde prevented the induction of ICGF by both thrombin (compare Fig 5H with 5B) and EDTA (compare Fig 5I with 5C).

Immunofluorescence microscopy (IF) shows the effect of thrombin and EDTA, and inhibitors of EC contraction on actin and ICGF. Actin was stained with rhodamine-labeled phalloidin. The camera shutter speed was set automatically so the intensities are not relative. These representative photos show that thrombin- but not EDTA-induced ICGF was blocked by the inhibitor, bromo-cAMP, and that both were blocked by the cross-linker, glutaraldehyde. HUVEC in the photos were (A) untreated; (B) thrombin-stimulated; (C) EDTA-treated; (D) incubated with bromo-cAMP before treating with control buffer; (E) incubated with bromo-cAMP before treating with thrombin; (F) incubated with bromo-cAMP before treating with EDTA; (G) incubated with glutaraldehyde before treating with control buffer; (H) incubated with glutaraldehyde before treating with thrombin; and (I) incubated with glutaraldehyde before treating with EDTA.

Immunofluorescence microscopy (IF) shows the effect of thrombin and EDTA, and inhibitors of EC contraction on actin and ICGF. Actin was stained with rhodamine-labeled phalloidin. The camera shutter speed was set automatically so the intensities are not relative. These representative photos show that thrombin- but not EDTA-induced ICGF was blocked by the inhibitor, bromo-cAMP, and that both were blocked by the cross-linker, glutaraldehyde. HUVEC in the photos were (A) untreated; (B) thrombin-stimulated; (C) EDTA-treated; (D) incubated with bromo-cAMP before treating with control buffer; (E) incubated with bromo-cAMP before treating with thrombin; (F) incubated with bromo-cAMP before treating with EDTA; (G) incubated with glutaraldehyde before treating with control buffer; (H) incubated with glutaraldehyde before treating with thrombin; and (I) incubated with glutaraldehyde before treating with EDTA.

Due to the variability among SS RBC samples, the effect of bromo-cAMP pretreatment on thrombin- and EDTA-induced SS RBC adherence shown in Fig 6 is presented as a percent of control adherence. In these studies adherence results were considered only when thrombin-enhanced RBC adherence was significantly different from the buffer-treated negative control. Again EDTA was used as a positive control for ICGF. Bromo-cAMP reduced mean thrombin-enhanced SS RBC adherence from 243% of baseline to 122% of baseline, but had no significant effect on EDTA-induced adherence. There were no significant differences in adherence to control EC treated with buffer alone (100%), to bromo-cAMP pretreated EC treated with buffer (92%), or to bromo-cAMP pretreated EC treated with thrombin (122%). These adherence effects paralleled the effects of bromo-cAMP on ICGF observed by IF (Fig 5D through F); bromo-cAMP blocked both adherence and gap formation induced by thrombin, but neither effect of EDTA. Pretreatment with glutaraldehyde reduced mean thrombin-enhanced SS RBC adherence from 238% to 120% of baseline, a level that was not significantly different from adherence control EC treated with buffer alone (100%) or to EC treated with glutaraldehyde (85%). Unlike bromo-cAMP, however, glutaraldehyde also significantly reduced EDTA-induced adherence from 323% to 120% of baseline. Like bromo-cAMP, glutaraldehyde did not alter baseline adherence. Again, the adherence effects paralleled the effects of glutaraldehyde on ICGF observed by IF (Figs 5G, H, and I); glutaraldehyde blocked both adherence and gap formation induced by either thrombin or EDTA.

Effect of inhibition of cell contraction by bromo-cAMP and glutaraldehyde on SS RBC adherence. Treatment of EC with bromo-cAMP prevented thrombin- but not EDTA-induced adherence. Treatment of EC with glutaraldehyde blocked both thrombin- and EDTA-induced adherence. Results are presented as a percent of control adherence.

Effect of inhibition of cell contraction by bromo-cAMP and glutaraldehyde on SS RBC adherence. Treatment of EC with bromo-cAMP prevented thrombin- but not EDTA-induced adherence. Treatment of EC with glutaraldehyde blocked both thrombin- and EDTA-induced adherence. Results are presented as a percent of control adherence.

These data suggest a correlation between ICGF and thrombin-induced static SS RBC adherence to cultured HUVEC. The link between ICGF and adherence is demonstrated by the cognate effects of bromo-cAMP and glutaraldehyde on both processes, whether stimulated by thrombin or by EDTA. Under conditions of thrombin exposure of 0.1 U/mL for 5 minutes, the doubling of static sickle cell adherence in selected endothelial cell monolayers was dependent on striking EC contraction and ICGF.

DISCUSSION

Our finding of a thrombin dose-response curve for SS RBC adherence to HUVEC (Fig 1) whose close resemblance to that for gap formation28 hints of an association between adherence and ICGF. Consequently, we confirm that our thrombin conditions also cause ICGF (Figs 3-5, Table 2). In the context of an overall doubling of SS RBC adherence in response to thrombin (Fig 2), the equivalent patterns of distribution of adherent SS RBC on untreated and thrombin-treated HUVEC monolayers (Table 1) indicates that there are comparable increases in adherence at all three locations, EC edges, EC apical surfaces, and intercellular matrix. The nonlinear nature of these changes is illustrated by comparing the 14-fold increase in exposed matrix with the twofold increase in adherence to this location and the corresponding, but reciprocal, changes of the area covered by EC. The lessening of adherence seen with higher thrombin concentrations (Fig 1) may relate to a proteolytic effect of thrombin on EC adhesive proteins, to the binding by EC of antithrombin III or α2-macroglobulin and consequent neutralization of thrombin effect,35-37 or to the loss of some cells in posttreatment washing, which we observed (data not shown).

The above relationships suggest that different adhesogenic mechanisms are likely to pertain for different locations of the vascular endothelium. Specifically, the doubling of adherence to EC edges and luminal surfaces may be due to the liberation of adhesive molecules normally occupied in EC tethering, such as β1 and β3 integrins,38 for binding RBC directly or via RBC-bound thrombospondin or Fn.7 Such increased adhesivity may be the result of increased availability of adhesive molecules, such as integrins, which have specificity for RBC,39 but which ordinarily reside on the abluminal EC surface,40 or of increased expression, adhesivity, or ligand affinity of those molecules.41-43 Increased binding within the induced gaps is understood reasonably as due to greater physical availability of adhesive matrix proteins that bind RBC, such as Fn,7 or perhaps as a result of residual EC adhesive proteins retained in the gaps after forceful cellular contraction. While thrombin is reported to modify matrix proteins by changing their synthetic rate,44 alternately spliced isoforms,45 and physical accessibility,46 some of these effects may require longer durations of thrombin exposure than those used in this study. The specific adhesive molecules involved in thrombin-stimulated adherence and their modulation by different thrombin concentrations are important issues that we are now investigating.

The significant increase in RBC adherence associated with the permissive induction of ICGF by EDTA or antilaminin polyclonal antibodies demonstrates that ICGF participates in enhanced adherence. The concordance between the effects of bromo-cAMP and glutaraldehyde on the ICGF and adherence induced by thrombin or EDTA (Figs 5 and 6) further supports the notion that ICGF participates in thrombin-enhanced adherence. Taken together, these findings demonstrate that under the conditions we used, thrombin increases SS RBC adherence and ICGF, that ICGF induced by other means also enhances SS RBC adherence, and that blocking the ICGF induced by thrombin also blocks its induction of adherence. These associations provide the basis for our conclusion that increased adherence and ICGF are interrelated.

The correlation between ICGF and thrombin-enhanced adherence breaks down with higher concentrations of thrombin, at which there was less adherence, but a similar degree of ICGF. This reduction of adherence (Fig 1), whether the result of a proteolytic effect of higher doses of thrombin on EC adhesive molecules or of neutralization of thrombin by factors having antithrombin activity,35-37 clearly demonstrates an imperfect association between thrombin-enhanced adherence and ICGF. However, this divergence of effects occurs at thrombin concentrations greatly exceeding levels predicted in vivo. The concentration we use, while similar to that used in other published studies on EC effects,15,28 actually exceeds those reported during clotting in vitro.47 Another potential dissociation of thrombin-induced effects stems from our having examined for gaps only those monolayers that demonstrated an adhesogenic response to thrombin. Documentation of ICGF in monolayers without adhesive responses also would have provided evidence against an absolute interdependence of adhesivity and ICGF responses. Our conclusions regarding thrombin action pertain to those monolayers that underwent an adhesogenic response.

Additional considerations support the pertinence in vivo of the ICGF we observed in vitro. First, the generation of thrombin on cell membranes48 inevitably increases local concentrations of thrombin. Second, EC effects of thrombin likely are potentiated by the abnormal levels of inflammatory cytokines and oxygen radicals present in sickle cell disease.49-52 Consistent with our proposition are the ICGF induced by thrombin in intact vessels ex vivo,53 the interendothelial cell gaps observed in pathologic sections from autopsied sickle cell patients,54and the finding in sickle cell blood of substantial numbers of circulating EC23 whose discharge into the circulating blood is predicted to have exposed vascular matrix between the retained cells. Further support for the potential pathophysiologic relevance of our observations derives from the occurrence of ICGF in vivo as part of the altered vascular permeability during acute inflammatory responses.26 In this regard, the long held association of vasoocclusive crises with infection and inflammation may relate to the abnormal levels of inflammatory cytokines in sickle cell disease and to the participation of PMN in SS RBC adherence and vasoocclusion. The participation of inflammatory mediators and PMN in both processes, ICGF and SS RBC adherence, support the notion that ICGF may be a part of the link by which inflammation and vasoocclusion may be related. In our in vitro adherence studies, the possible influence of PMN is minimized by their removal during the preparation of SS RBC for those experiments. However, these interacting influences raise important questions and deserve independent study.

Other EC effects of thrombin that are predicted to influence adherence include the secretion of vWF,55 which mediates SS RBC adherence,56 the induction of nitric oxide synthesis,57 which modulates the expression of certain cytoadhesive molecules,58 and the production of prostacyclin, which protects against PMN adherence and vascular damage.59 The protective effect of prostacyclin on vascular endothelium does not seem to pertain in our experiments, possibly because the amount of prostacyclin produced relative to the concentration of thrombin used is insufficient to prevent ICGF. Our use of 17% heparinized plasma in the adherence assay may have inhibited thrombospondin-mediated adherence60 61 and, thereby, restricted the group of adhesive molecules tested. This limitation would not be expected to affect our fundamental observations and conclusions, partly because these proteins, eg, P-selectin, are less important to firm than to rolling adhesion.

In view of the uncertain distinctions between EC stimulation, activation, and injury,62,63 our findings are consistent with the report of enhanced SS RBC adherence to EC “injured” by interleukin-1.64 Our findings contrast, however, with evidence that thrombin has no effect on the flow adherence of SS RBC suspended in plasma-free buffer to microvascular EC exposed continuously to thrombin during the 10 minutes of the assay.39 Experimental differences between the studies include the assay methods, properties of HUVEC and microvascular EC, enhancement of adherence by autologous plasma (our data not shown), and likely abrogation of thrombin effect by prolonged exposure of EC to the protease. The differences in results could be accounted for by any of these factors independently,9 which would include shear forces minimizing thrombin-enhanced adherence and exposed matrix proteins having a greater effect on static adherence. These factors deserve separate investigation.

The much greater variability of SS RBC adherence compared with that of AA RBC we describe has been observed by others.9 This may result in part from the reported variance in SS RBC adherence, which correlates with clinical severity65 or from the greater adhesiveness found during crises.66 The determinants of this variability remain to be defined fully. It is probable that the degree of adherence may relate to changes in the quantity or adhesivity of receptors born on SS RBC and EC, variation in the representation of SS RBC subpopulations having different adhesive properties, and to fluctuations in the concentrations of adhesive ligands in the plasma.

Regarding the relevance of our observations to sickle cell disease, it is clear that the adhesivity of HUVEC for AA RBC, as well as for SS RBC, increases in response to thrombin (albeit to a lesser degree). The direct effects of thrombin on EC do not require the presence of SS RBC. However, it is not necessary that pathophysiologic relevant processes be specifically unique to sickle cell disease. In this regard, nonspecific RBC adherence impacts more severely on microcirculatory flow of poorly deformable SS RBC, which are prone to being trapped behind a nidus of occlusion, than on normally deformable AA RBC.6 Our observations may be relevant to an adherent event capable of initiating the “vicious cycle of erythrostasis.”67

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We wish to thank Drs Robert Pytela, Irena Klimanskaya, Gilda Barabino, and Tim Wick for valuable scientific discussions and advice, Glen Ozoa for technical assistance, the staff of San Francisco General Hospital Labor and Delivery for the supply of umbilical cords, and Dr William C. Mentzer for the use of his fluorescent microscope.

Supported in part by Grant No. HL 20985 from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD.

Address reprint requests to Stephen H. Embury, MD, Building 100, Rm 263, San Francisco General Hospital, San Francisco, CA 94110; e-mailsembury@itsa.ucsf.edu.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked "advertisement" is accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal