Abstract

Regulation of topoisomerase II (TOPO II) isozymes and β is influenced by the growth and transformation state of cells. Using HL-60 cells induced to differentiate by all-trans retinoic acid (RA), we have investigated the expression and regulation of TOPO II isozymes as well as the levels of topoisomerase I (TOPO I). During RA-induced differentiation of human leukemia HL-60 cells, levels of TOPO I remained unchanged, whereas the levels and phosphorylation of TOPO II and TOPO IIβ proteins were increased twofold to fourfold and fourfold to eightfold, respectively. The elevation of TOPO II ( and β) protein levels and phosphorylation was apparent at 48 hours of treatment with RA and persisted through 96 hours. The increased level of TOPO IIβ protein was also detected in differentiated cells subsequently cultured for 96 hours in RA-free medium. Pulse chase experiments in cells labeled with 35S-methionine showed that the rate of degradation of TOPO IIβ protein in control cells was about twofold faster than that in the differentiated RA-treated cells. The level of decatenation activity of kDNA was comparable in nuclear extracts from control or RA-treated cells. Whereas etoposide (1 to 10 μmol/L) -induced DNA cleavage was not significantly different, apoptosis was significantly lower (P = .012) in RA-treated versus control cells after exposure to 10 μmol/L etoposide. Consistent with unaltered levels of TOPO I, camptothecin (CPT) -induced DNA cleavage was similar in control or RA-treated cells. However, apoptosis after exposure to 1 to 10 μmol/L CPT was significantly lower (P = .003 to P < .001) in RA-treated versus control cells. Results suggest that TOPO IIβ protein levels are posttranscriptionally regulated and that degradation of TOPO IIβ is decreased during RA-induced differentiation. Furthermore, whereas the total level of TOPO II ( + β) is increased with RA, the level of TOPO II catalytic activity and etoposide-stabilized DNA cleavage activity remains unaltered. Thus, TOPO IIβ may have a specific role in transcription of genes involved in differentiation with RA treatment.

© 1998 by The American Society of Hematology.

THE TOPOISOMERASES are key nuclear enzymes that alter DNA topology for the efficient processing of genetic material.1,2 This is accomplished by the generation of single-strand and double-strand breaks in DNA catalyzed by topoisomerase I (TOPO I) and topoisomerase II (TOPO II), respectively. Among the topoisomerases,1,2 TOPO I exists as a single 97-kD protein, whereas TOPO II has two distinct isoforms of molecular weight (Mr) 170,000 (α) and 180,000 (β). A critical role for TOPO II has been suggested in recombination, replication, chromosome structure, and segregation.1,2 Although the topoisomerases are essential enzymes for cell function, they also represent targets for a number of clinically important agents used in the chemotherapy of cancer.1-5

The role of TOPO IIα in cell proliferation and as a target for antitumor agents has been extensively studied.1-5 However, the precise functional role of TOPO IIβ during cell growth and/or differentiation has been elusive. Specific alterations in the phosphorylation state of TOPO IIβ is seen in mitotic cells and this enzyme has also been suggested to be a potential target for the antitumor agent mitoxantrone.6-9 Woessner et al10,11 were the first to report the potential role of TOPO IIβ in cell differentiation. Subsequently, it was demonstrated that the genes for the α and β isoforms of TOPO II are expressed in a varied manner in proliferating versus differentiated tissue,12 and a specific role for TOPO II in neutrophil-granulocyte differentiation has been suggested.13,14 Kaufmann et al,15,16 evaluating the role of topoisomerases during granulocytic maturation of HL-60 cells induced with dimethyl sulfoxide, suggested that both protein levels and actvity of TOPO I and TOPO IIα were reduced in differentiated cells. Similarly, based on phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate–induced differentiation of HL-60 cells, an apparent link between a decrease in topoisomerase II levels and growth and differentiation has been suggested.17-19

The role of retinoic acid as an inducer of differentiation has received considerable attention because of the potential role of retinoid-regulated transcription. Given the complexity of cell differentiation and the potential regulation of these events by retinoids,20 we were prompted to explore the role of topoisomerases during granulocytic maturation of HL-60 cells induced by all-trans retinoic acid (RA). Also, the availability of TOPO IIβ isoform-specific antisera with utility in both immunoblotting and immunoprecipitation procedures provided an opportunity to specifically address the differential regulation of TOPO II isoforms.21Our results demonstrate that, although TOPO I is unaffected, there is an anomalous relationship between the expression of TOPO IIα and β proteins and activity. Furthermore, during RA-induced differentiation of HL-60 cells, there is an increased upregulation of TOPO II, particularly the TOPO IIβ isoform, apparently by a posttranscriptional mechanism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The parental HL-60 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD). Cultures were maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 2 mmol/L L-glutamine (M.A. Bioproducts, Gaithersburg, MD) at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 plus 95% air atmosphere. Under these conditions, the doubling time in vitro of the HL-60 cells was 40 to 45 hours.

The HL-60 cells were treated with 1 μmol/L RA for as long as 120 hours, and at various time intervals during this period the control and RA-treated cells were analyzed for (1) proliferation and differentiation; (2) protein levels of TOPO I; (3) mRNA, protein, and phosphorylation of TOPO IIα and β; and (4) induction of etoposide (VP-16) or camptothecin (CPT)-induced DNA damage and apoptotic response. The effects of RA (1 μmol/L) on cell proliferation and induction of differentiation were determined by counting cells in a hemacytometer and the ability of cells to reduce nitroblue tetrazolium, respectively.22

Analysis of mRNA levels of TOPO IIα and β in control and RA-treated cells was performed using an RNase protection assay.23,24The human TOPO IIα and β probes were prepared as described previously and generated a 215-bp (α), 228-bp (β1), and 292-bp (β2) protected fragment.23,24 The α1-globin probe generated a 133-bp fragment.23,24Briefly, RNase protection analysis was performed on 20 μg of total RNA extracted from cells using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Total RNA was hybridized with TOPO IIα and β antisense probes and 1 μg of total RNA from K562 cells (which strongly overexpress α1-globin) was spiked into the reactions as an exogenous control and detected with α1-globin antisense probe as described earlier.23,24 All RNase protection assays were performed as previously described.23 24

TOPO I or TOPO IIα and β protein levels were determined in extracts from control and treated cells by immunoblotting. Briefly, cells were lysed in RIPA buffer and protein content was determined. Lysates containing equal amounts of protein were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), electroblotted onto nitrocellulose,25 and probed with antibodies for TOPO I26 and antibodies for TOPO II that simultaneously15,16 or individually21 recognize the α and β isoforms.

Phosphorylation of the α and β isoforms of TOPO II was determined in control and RA-treated cells metabolically labeled with [32P]-orthophosphoric acid.25 Briefly, control and RA cells were labeled with [32P]-orthophosphoric acid for 2 to 4 hours and lysed in RIPA buffer supplemented with 0.35 mol/L NaCl, and the TOPO II was immunoprecipitated25 with an antibody that simultaneously or individually recognizes the α and β isoforms of TOPO II. The immunoprecipitate was resolved by SDS-PAGE, and the signal intensity was determined with a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA).

Phosphopeptide analysis of the immunoprecipitated 180-kD (β) TOPO II was performed as described by Wells et al27 and Boyle et al.28 Briefly, the band corresponding to the 180-kD (β) TOPO II protein was excised from the dried, unfixed gel and then eluted with 50 mmol/L ammonium bicarbonate, 0.1% SDS, and 0.5% 2-mercaptoethanol overnight. The protein was precipitated with 15% to 20% trichloroacetic acid and oxidized with performic acid. Protein samples were digested overnight in TPCK-trypsin, and phosphopeptides were analyzed by electrophoresis with pH 1.9 buffer in the horizontal dimension and chromatography in the vertical dimension using phospho-chromatography buffer.27 28

Synthesis and degradation of TOPO IIβ was determined in control or RA-treated cells metabolically labeled with [35S]-L-methionine Tran 35S-Label for 3 hours.29 After labeling, cells were washed twice and reincubated in complete medium supplemented with 0.1 mmol/L L-methionine. Samples of cells were retrieved at 0, 2, 4, and 6 hours, and the TOPO IIβ was immunoprecipitated from cell lysates as described earlier.29 Signal intensity was quantified in a PhosphorImager.

CPT (0.5 to 10 μmol/L) or etoposide (1 to 10 μmol/L)-stabilized DNA cleavable complex formation and apoptosis in control and RA-treated cells were determined by the SDS-KCl technique25 and labeling with fluorescein-12-dUTP,30 respectively, after drug treatment for 1 hour. Control or RA-treated cells after drug treatment were reincubated in drug-free medium for 4 hours before labeling30 for analysis of apoptotic cells.

RESULTS

The data in Fig 1 outline the growth and differentiation of control and RA-treated HL-60 cells. It is apparent that, in contrast to the control cells, there is minimal proliferation beyond 48 hours in the RA-treated cells. Furthermore, differentiation (based on reduction of nitroblue tetrazolium) progressively increases and is essentially complete by 96 hours. In cells harvested at 96 hours and washed and reincubated in fresh medium, the cells maintain the differentiated phenotype for periods as long as 120 hours (data not shown).

Growth (A) and differentiation (B) of human leukemia HL-60 cells treated with 1 μmol/L RA.

Growth (A) and differentiation (B) of human leukemia HL-60 cells treated with 1 μmol/L RA.

Immunoblot analysis of TOPO I levels in control and RA-treated cells showed that neither the proliferation nor the differentiation state of the cells impacted upon the level of TOPO I protein (Fig2).

Immunoblot of TOPO I levels using antibody C2126 in control and RA-treated HL-60 cells.

Immunoblot of TOPO I levels using antibody C2126 in control and RA-treated HL-60 cells.

The mRNA expression of TOPO IIα, β1, and β2 (2 differentially spliced forms) in control and RA-treated cells is shown in Fig 3. Interestingly, despite the growth cessation by 48 hours, mRNA levels of TOPO IIα, β1, and β2 in RA-treated cells were maintained at 60% to 80% of the level in control, untreated cells. A maximal decrease (50% to 60%) in TOPO II mRNA levels occurs at 96 hours. Furthermore, in cells treated with RA for 120 hours and reincubated in fresh RA-free medium, levels of TOPO II mRNA were maintained at 50% to 60% of control levels.

(A) RNase protection analysis of TOPO II, β1, and β2 in control (lanes 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 at 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 hours and 120R [recovery in medium after treatment for 120 hours], respectively) and RA-treated (lanes 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, and 13 at 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 hours and 120R [recovery in medium after treatment for 120 hours], respectively) HL-60 cells. M is the molecular weight marker, and lane 1 is tRNA. (B) Phosphorimager analysis of TOPO II isozymes mRNA relative to globin. The signal intensity of the sample from control cells at 24 hours was set at 100%.

(A) RNase protection analysis of TOPO II, β1, and β2 in control (lanes 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 at 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 hours and 120R [recovery in medium after treatment for 120 hours], respectively) and RA-treated (lanes 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, and 13 at 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 hours and 120R [recovery in medium after treatment for 120 hours], respectively) HL-60 cells. M is the molecular weight marker, and lane 1 is tRNA. (B) Phosphorimager analysis of TOPO II isozymes mRNA relative to globin. The signal intensity of the sample from control cells at 24 hours was set at 100%.

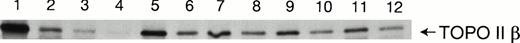

The protein level and phosphorylation of TOPO IIα and β in control and RA-treated cells is outlined in Figs 4 and5, respectively. The data in Fig 4 show that levels of TOPO IIα are elevated twofold to fourfold in cells treated with RA. Also, maximal elevation in levels of TOPO IIα appears to occur around 96 hours, which coincides with the state of maximal differentiation. The levels of TOPO IIβ were also elevated in response to the differentiated state of the cells, with a twofold to fourfold elevation between 48 and 96 hours. The immunoprecipitation data shown in Fig 5 demonstrate that elevated levels of TOPO IIα or β protein also correspond with an increased phosphorylated state of the protein. However, whereas the increase in phosphorylation of TOPO IIα in RA-treated cells was about twofold higher (compared with the untreated control), the level of TOPO IIβ phosphorylation in RA-treated cells was greater than fourfold. Based on this differential response, a majority of additional experiments were focused on the regulation of TOPO IIβ.

(A) Immunoblot analysis of TOPO II and β levels using serum IID (15) in control (C) and RA (R)-treated HL-60 cells. (B) Analysis of TOPO II and β protein levels by measurement of optical density.

(A) Immunoblot analysis of TOPO II and β levels using serum IID (15) in control (C) and RA (R)-treated HL-60 cells. (B) Analysis of TOPO II and β protein levels by measurement of optical density.

(A) Phosphorylation of TOPO II and β in control (C) and RA (R) -treated HL-60 cells. Control and RA-treated cells were metabolically labeled with [32P]-orthophosphoric acid, and cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with serum IID (15) and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. (B) Phosphorimager analysis of TOPO II and β isozyme phosphorylation.

(A) Phosphorylation of TOPO II and β in control (C) and RA (R) -treated HL-60 cells. Control and RA-treated cells were metabolically labeled with [32P]-orthophosphoric acid, and cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with serum IID (15) and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. (B) Phosphorimager analysis of TOPO II and β isozyme phosphorylation.

To determine mechanisms responsible for the more pronounced increase in levels of TOPO IIβ in the RA-treated cells, the stability of the protein in control and RA-treated cells pulse labeled with [35S]-L-methionine was determined. Results from these experiments ( Fig 6 and Table 1) suggest that the levels of TOPO IIβ in cells treated with RA are twofold higher compared with that in untreated cells.

Degradation of TOPO IIβ in control and RA-treated HL-60 cells. Control cells (lanes 1 through 4), 48-hour RA-treated cells (lanes 5 through 8), and 96-hour RA-treated cells (lanes 9 through 12). Lanes 1, 5, and 9, protein level immediately after labeling with35S-methionine; lanes 2, 6, and 10, labeled protein levels at 2 hours after reincubation in complete medium; lanes 3, 7, and 11, labeled protein levels at 4 hours after reincubation in complete medium; and lanes 4, 8, and 12, labeled protein levels at 6 hours after reincubation in complete medium.

Degradation of TOPO IIβ in control and RA-treated HL-60 cells. Control cells (lanes 1 through 4), 48-hour RA-treated cells (lanes 5 through 8), and 96-hour RA-treated cells (lanes 9 through 12). Lanes 1, 5, and 9, protein level immediately after labeling with35S-methionine; lanes 2, 6, and 10, labeled protein levels at 2 hours after reincubation in complete medium; lanes 3, 7, and 11, labeled protein levels at 4 hours after reincubation in complete medium; and lanes 4, 8, and 12, labeled protein levels at 6 hours after reincubation in complete medium.

Degradation of TOPO IIβ in Control and RA-Treated HL-60 Cells

| Hours . | Control . | 48 h RA Treatment . | 96 h RA Treatment . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 52 ± 18 | 81 ± 28 | 62 ± 22 |

| 4 | 30 ± 14 | 69 ± 12 | 71 ± 25 |

| 6 | 13 ± 9 | 44 ± 7 | 25 ± 5 |

| Hours . | Control . | 48 h RA Treatment . | 96 h RA Treatment . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 52 ± 18 | 81 ± 28 | 62 ± 22 |

| 4 | 30 ± 14 | 69 ± 12 | 71 ± 25 |

| 6 | 13 ± 9 | 44 ± 7 | 25 ± 5 |

Cells were labeled with [35S]-L-methionine for 2 hours. Values are the percentage of [35S]-label remaining ± standard error.

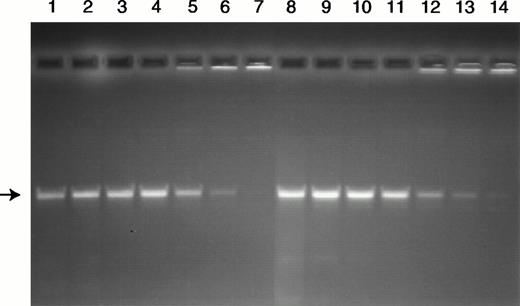

Because the levels and phosphorylation of the TOPO II isozymes were increased in RA-treated cells, the catalytic activity based on decatenation of kDNA was determined. Results from these experiments (Fig 7) demonstrate that, despite the increased protein levels and phosphorylation of the TOPO II isozymes in the RA-treated cells, the total level of decatenating activity is comparable in extracts from control and RA-treated cells.

Analysis of decatenating activity in nuclear extracts from control (lanes 1 through 7) and RA-treated (lanes 8 through 14) HL-60 cells. The substrate 200 ng kDNA (TOPOGEN Inc) was incubated for 30 minutes with nuclear extracts that were serially diluted to contain the following: lanes 1 and 8 (1:2), lanes 2 and 9 (1:4), lanes 3 and 10 (1:8), lanes 4 and 11 (1:16), lanes 5 and 12 (1:32), lanes 6 and 13 (1:64), and lanes 7 and 14 (1:128). The position of the decatenated kDNA is indicated by the arrow.

Analysis of decatenating activity in nuclear extracts from control (lanes 1 through 7) and RA-treated (lanes 8 through 14) HL-60 cells. The substrate 200 ng kDNA (TOPOGEN Inc) was incubated for 30 minutes with nuclear extracts that were serially diluted to contain the following: lanes 1 and 8 (1:2), lanes 2 and 9 (1:4), lanes 3 and 10 (1:8), lanes 4 and 11 (1:16), lanes 5 and 12 (1:32), lanes 6 and 13 (1:64), and lanes 7 and 14 (1:128). The position of the decatenated kDNA is indicated by the arrow.

Based on the more prominent increase in the phosphorylation of TOPO IIβ in the RA-treated cells, possible alterations in site-specific phosphorylation were determined in complete tryptic digests by two-dimensional mapping. The results shown in Fig 8indicate that, although a site appears to be hypophosphorylated in the RA-treated cells, four additional sites are hyperphosphorylated in the RA-treated versus control cells.

Representative two-dimensional tryptic phosphopeptide maps of TOPO IIβ protein from control (left) and RA-treated (right) HL-60 cells. Cells were metabolically labeled with [32P]-orthophosphoric acid, and lysates in RIPA buffer were immunoprecipitated with antiserum specific for TOPO IIβ. Peptides were separated horizontally by electrophoresis at pH 1.9 and vertically by chromatography as described in Materials and Methods. The sites that are differentially phosphorylated between control and RA-treated cells are identified by arrows.

Representative two-dimensional tryptic phosphopeptide maps of TOPO IIβ protein from control (left) and RA-treated (right) HL-60 cells. Cells were metabolically labeled with [32P]-orthophosphoric acid, and lysates in RIPA buffer were immunoprecipitated with antiserum specific for TOPO IIβ. Peptides were separated horizontally by electrophoresis at pH 1.9 and vertically by chromatography as described in Materials and Methods. The sites that are differentially phosphorylated between control and RA-treated cells are identified by arrows.

It is well recognized that CPT and VP-16 are effective in stimulating DNA cleavable complex formation mediated by TOPO I and TOPO II, respectively.3-5 To assess the sensitivity of control and RA-treated differentiating cells to the DNA-damaging effects of CPT or VP-16, we evaluated drug-stimulated DNA cleavable complex formation by the SDS-KCl technique.25 Results from these experiments are outlined in Table 2. The data suggest that, except for a decrease in DNA cleavable complex formation in cells treated with 10 μmol/L VP-16, the DNA cleavable complex formation induced by VP-16 or CPT in control or RA-treated cells is not significantly different (P = .6 to .13).

Effect of Treatment With RA on Drug-Stimulated DNA Cleavable Complex Formation and Apoptosis in HL-60 Cells

| Drug Treatment* . | Control . | RA Treated . | P† . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 μmol/L CPT | |||

| DNA C.C. | 2.6 ± 0.8‡ | 3.1 ± 1.0‡ | .6 |

| % Apoptosis | ND | ND | |

| 1 μmol/L CPT | |||

| DNA C.C. | 3.8 ± 0.4‡ | 4.4 ± 0.5‡ | .19 |

| % Apoptosis | 2.6 ± 0.31-153 | 1.7 ± 0.21-153 | .003 |

| 5 μmol/L CPT | |||

| DNA C.C. | 9.3 ± 0.8 | 8.2 ± 1.1 | .22 |

| % Apoptosis | 20.2 ± 3.5 | 11.6 ± 3.7 | .006 |

| 10 μmol/L CPT | |||

| DNA C.C. | 12.7 ± 2.4 | 9.2 ± 2.0 | .13 |

| % Apoptosis | 27.4 ± 3.7 | 16.5 ± 3.6 | <.001 |

| 1 μmol/L VP-16 | |||

| DNA C.C. | 2.6 ± 0.4 | 2.2 ± 0.4 | .27 |

| % Apoptosis | 1.0 ± 0.5 | 1.7 ± 1.2 | .4 |

| 10 μmol/L VP-16 | |||

| DNA C.C. | 8.8 ± 3.7 | 4.9 ± 0.9 | .15 |

| % Apoptosis | 10.5 ± 3.7 | 4.7 ± 1.5 | .012 |

| Drug Treatment* . | Control . | RA Treated . | P† . |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 μmol/L CPT | |||

| DNA C.C. | 2.6 ± 0.8‡ | 3.1 ± 1.0‡ | .6 |

| % Apoptosis | ND | ND | |

| 1 μmol/L CPT | |||

| DNA C.C. | 3.8 ± 0.4‡ | 4.4 ± 0.5‡ | .19 |

| % Apoptosis | 2.6 ± 0.31-153 | 1.7 ± 0.21-153 | .003 |

| 5 μmol/L CPT | |||

| DNA C.C. | 9.3 ± 0.8 | 8.2 ± 1.1 | .22 |

| % Apoptosis | 20.2 ± 3.5 | 11.6 ± 3.7 | .006 |

| 10 μmol/L CPT | |||

| DNA C.C. | 12.7 ± 2.4 | 9.2 ± 2.0 | .13 |

| % Apoptosis | 27.4 ± 3.7 | 16.5 ± 3.6 | <.001 |

| 1 μmol/L VP-16 | |||

| DNA C.C. | 2.6 ± 0.4 | 2.2 ± 0.4 | .27 |

| % Apoptosis | 1.0 ± 0.5 | 1.7 ± 1.2 | .4 |

| 10 μmol/L VP-16 | |||

| DNA C.C. | 8.8 ± 3.7 | 4.9 ± 0.9 | .15 |

| % Apoptosis | 10.5 ± 3.7 | 4.7 ± 1.5 | .012 |

Control and RA-treated (96 hours) HL-60 cells were evaluated for drug-stimulated DNA cleavable complex (DNA C.C.) formation by the SDS-KCl technique25 and apoptosis by the TUNEL assay using fluorescein-12-dUTP.30

Abbreviation: ND, not determined.

Control and RA-treated (96 hours) HL-60 cells were incubated at 37°C with the indicated concentrations of CPT (TOPO I poison) or VP-16 (TOPO II poison) for 1 hour.

t-test P values of differences in DNA C.C. and the percentage of apoptosis between control and RA-treated groups.

Fold-increase in drug-stimulated DNA cleavable complex formation compared to the untreated control. Values are the mean ± standard deviation from at least triplicate experiments.

% Apoptosis. Values are mean ± standard deviation from at least triplicate experiments.

DNA damage induced by VP-16 or CPT results in an apoptotic response in treated cells.3,4 To determine the apoptotic response of control or differentiated HL-60 cells after drug-stabilized topoisomerase-mediated DNA cleavable complex formation, we used a modification of the TUNEL assay.30 Results on induction of apoptosis based on staining with fluorescein-12-dUTP are shown in Table2. The data suggest that, after exposure for 1 hour to 1, 5, and 10 μmol/L CPT or 10 μmol/L VP-16, the apoptosis is significantly lower (P = .012 to P < .001) in RA-treated cells compared with the control untreated cells.

DISCUSSION

The retinoids are an important class of agents in their ability to induce cellular differentiation. In the HL-60 model system, RA induces maturation in the granulocytic lineage and this process has been well characterized.31 Accompanying the induction of cellular differentiation by RA, numerous membrane, cytoplasmic, and nuclear changes have been identified in HL-60 cells.31,32 Although the role of TOPO IIβ in cell differentiation has been suggested,12 this is the first report demonstrating a more pronounced upregulation of the β isoform during the differentiation process in HL-60 cells. Notably, TOPO II and not TOPO I is actively regulated during RA-induced differentiation. This differential effect may also reflect the active role of TOPO II versus TOPO I during cell growth and differentiation.

A number of earlier reports focusing on TOPO IIα have implied that the downregulation at the mRNA and protein level after treatment with dimethyl sulfoxide or phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate reflects cessation of growth after commitment to differentiate.15-18The results from this study are in agreement with the downregulation of TOPO IIα and β mRNA that occurs within 24 hours after exposure to RA.20 However, unlike treatment with dimethyl sulfoxide or phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate, our results demonstrate that, whereas the protein levels of TOPO I remain unchanged, protein levels of both TOPO IIα and β are elevated in HL-60 cells induced to differentiate after treatment with RA. It should also be noted that mRNA levels of both TOPO II isoforms are not only continuously maintained at 50% to 60% of control levels during the process of differentiation, but are also maintained in the differentiated state with an elevation in TOPO IIα and β protein levels in RA-treated cells. Also, upregulation of TOPO IIβ protein levels appear to be more pronounced than the α isoform. The higher levels of TOPO II protein in RA-treated cells also represents active protein, because the catalytic activity, measured by decatenation of kDNA, was similar in control and RA-treated cells. Increased levels of TOPO IIβ protein in the RA-treated cells appear to be due to slower degradation of the protein. The TOPO IIα and β in differentiated cells was also posttranslationally modified by phosphorylation, similar to the control cells. The level of phosphorylation was higher in the differentiated versus control cells, in accordance with the higher TOPO II protein level. These results on increased phosphorylation of TOPO II are comparable to the results of Chresta et al33 after treatment with RA for only 1 to 2 hours. Also, the increased phosphorylation of TOPO II in the RA-treated cells is of interest, because they are growth arrested in G1 phase of the cell cycle after differentiation. However, unlike data with mitotic cells,7-9 no apparent change in the molecular weight of TOPO IIβ was apparent with the phosphorylated form in RA-treated cells. Interestingly, the data also showed that four peptides in the TOPO IIβ protein are differentially hyperphosphorylated in RA-treated versus control cells when complete tryptic digests were analyzed by two-dimensional peptide mapping. Because there is a much greater degree of sequence similarity in the ATPase and breakage/reunion domains than the C-terminal domain between the α and β isoforms of TOPO II, the role of site-specific phosphorylation needs to be addressed. Our ongoing studies are now focused in sequencing the hyperphosphorylated sites of TOPO IIβ to characterize their functional role in catalytic and drug-stimulated DNA cleavage activity during growth and differentiation of RA-treated cells.

Despite the increased levels of TOPO II protein in RA versus control cells, the overall increase in CPT-stimulated or VP-16–stimulated DNA cleavable complex formation was comparable and not significantly different. However, apoptosis in response to the DNA damage was significantly lower in RA-treated versus control cells treated with 1, 5, and 10 μmol/L CPT or 10 μmol/L VP-16. The finding that drug-stabilized DNA cleavable complex formation and decatenation of kDNA are similar in the control and RA-treated cells suggests activity of the enzyme, but there may be a differential regulation in the processing of the breaks leading to apoptosis in control (proliferating) versus differentiated (nonproliferating) cells. The activity of TOPO II in the differentiated, nonproliferating cells is of interest, because circulating lymphocytes are essentially devoid of TOPO II-mediated DNA decatenating activity.

In summary, results from this study demonstrate that TOPO II levels are posttranscriptionally regulated in HL-60 cells induced to differentiate with RA. These results with RA and its relationship to the levels and activity of TOPO II isoforms is substantially different from the reports using dimethyl sulfoxide or phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate, suggesting that RA-induced effects on cell differentiation may actively involve a role for TOPO II. Furthermore, among the TOPO II isoforms, the β isoform appears to be more actively regulated in the RA-treated cells. Further studies delineating the role of TOPO II isoforms, particularly that of TOPO IIβ in differentiated cells, could aid in the identification of a specific role for these enzymes in transcription of genes involved in differentiation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors gratefully acknowledge Dr Scott Kaufmann (Department of Pharmacology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN) for the gift of anti-topoisomerase II antibody and Jim Reed of the Art-Medical Illustrations and Photography Department for skillful preparation of the figures.

Supported by US Public Health Services Grant No. CA35531 from the Department of Health and Human Services (M.A., D.R.G, K.A.K, and R.G.) and by the Imperial Cancer Research Fund (R.J.I. and I.D.H.).

Address reprint requests to Ram Ganapathi, PhD, Cancer Center, M38, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, 9500 Euclid Ave, Cleveland, OH 44195.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked "advertisement" is accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

![Fig. 3. (A) RNase protection analysis of TOPO II, β1, and β2 in control (lanes 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 at 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 hours and 120R [recovery in medium after treatment for 120 hours], respectively) and RA-treated (lanes 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, and 13 at 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 hours and 120R [recovery in medium after treatment for 120 hours], respectively) HL-60 cells. M is the molecular weight marker, and lane 1 is tRNA. (B) Phosphorimager analysis of TOPO II isozymes mRNA relative to globin. The signal intensity of the sample from control cells at 24 hours was set at 100%.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/92/8/10.1182_blood.v92.8.2863/5/m_blod42020003w.jpeg?Expires=1769146819&Signature=OjOZKXDdudjydQI3bx1NGX40~38yZao8hRN0aAK4zy6~zYB18J5Ob7o6InOpFvup-XEA5alaNrczDpfIKz09zoqvkRN9RwONNhF5xN8ZkkzoEuixv~RJ99qPbh7TgxHd~BRKmzf0OYEnbX83Yxc9ovVGexAzX7WFASY0VK-ve4D1kCZFv0frRgb71h4TFMacaP6-OhNjqACb3XJNNDep0Z42fZ2NlnHvQGr-cCfrJ9jLeRx4-CPyprjoaGCmN~tlMeZz4RKtYZG06lCgOXvYwqcv58IfxzLKseiZ5wBHWGVAoYn07t~LZhDQb2vhAuht-pEk7rdLI1Juf7jRcAo32g__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 5. (A) Phosphorylation of TOPO II and β in control (C) and RA (R) -treated HL-60 cells. Control and RA-treated cells were metabolically labeled with [32P]-orthophosphoric acid, and cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with serum IID (15) and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. (B) Phosphorimager analysis of TOPO II and β isozyme phosphorylation.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/92/8/10.1182_blood.v92.8.2863/5/m_blod42020005aw.jpeg?Expires=1769146819&Signature=2QXwdJ-0lVlTkv9cOHcp6zzR5HCUxDPbtjRXtOUY0Pdcj6WW4LdT37To3x2GdVGj6zEZSLowtBPWlKJhHXsNb3lJJ-cd8Qfemoy8ZdQ2aLZIBvD6qxq1jA6~TuNmOEHBSa5uXD6ogiCuo1D62afN8xjPJ0y6pdsMZxFQLgnq2vJgfudcydY8j8K1vjkV4T5xHAWBdARQX5CLptlTHGejDLVlCD0zCx97XC9Ik8NQSIDQWIJEg1EN5cJPgEllyneeMeS5gw8KHd65DnJRFH2wfL9jyqMWnLWeY7zM5TxYT4xILtMValhAbRJ8BUlxZaVEQMdFTZTFAr5Cpb0i4kqUog__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 5. (A) Phosphorylation of TOPO II and β in control (C) and RA (R) -treated HL-60 cells. Control and RA-treated cells were metabolically labeled with [32P]-orthophosphoric acid, and cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with serum IID (15) and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. (B) Phosphorimager analysis of TOPO II and β isozyme phosphorylation.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/92/8/10.1182_blood.v92.8.2863/5/m_blod42020005bx.jpeg?Expires=1769146819&Signature=RN31JCVb~LB4jpH4MyzuW1tS9lNy-u2wNfIljTUQfuOstLt3yDZA1w2pXUyNl2W6Mp-JjfqXbtzw6Sqakr-eZZITW2sL3pOWcTkHY5aPy7FZPfz6ARsG9QrjXc2PgwEDhUYiZk-9wn3KcfVzqFJvAHx1h8b1PE9GZdygRgr1nPZdxgXKCRjXodHuoasoMZYw2fFjWwlE15VfFmFrMy9PeFKTBoLeRQqxi-bFgmNedBaKzToI6lBsWJGrnLrMKhDQjuK~1HOjFbFw~Axx~bFQQ5zPdZkT-xPXFYtQt2zNEt~tAYFGqic-OgQN~vYNJBbhacdw3F3guVKivJbRxg6cTw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 8. Representative two-dimensional tryptic phosphopeptide maps of TOPO IIβ protein from control (left) and RA-treated (right) HL-60 cells. Cells were metabolically labeled with [32P]-orthophosphoric acid, and lysates in RIPA buffer were immunoprecipitated with antiserum specific for TOPO IIβ. Peptides were separated horizontally by electrophoresis at pH 1.9 and vertically by chromatography as described in Materials and Methods. The sites that are differentially phosphorylated between control and RA-treated cells are identified by arrows.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/92/8/10.1182_blood.v92.8.2863/5/m_blod42020008w.jpeg?Expires=1769146819&Signature=x80Mrcag7Wr845kMDvaN049nY1LN~J29b8q~-4XU~cKg43r~8ZNWcobbAPeNxsWU-RZTFeWwTnzffl4kGmqKcQbHMv9G~QKrVNSoTh~QQ148XBaZFmGOwn9W5pyxuSH9WYEL~0Js6ms5rrD1D6N2W~lCff1zkEfMCVGK2zU16kDuHXmh1QZif8nq3ik0YDIJT-swSoptxKQJ5tAgtTOkTE3oWo7O72vHC0o9c-nNSg52OUIuG1p2ybA1q8ANTQbvCJzZty2bmhnaNBNU4NBEmG5Kyr49xR1rXBVLnH-8eIsdomdqh6p-y3Kqty8aEvSC9~7aeMIZ6R4Y2aTaWjapxg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal