Abstract

When human monocytes or alveolar macrophages are cultured in the presence of interleukin (IL)-4 or IL-13, the expression of the reticulocyte-type 15-lipoxygenase is induced. In mice a 15-lipoxygenase is not expressed, but a leukocyte-type 12-lipoxygenase is present in peritoneal macrophages. To investigate whether both lipoxygenase isoforms exhibit a similar regulatory response toward cytokine stimulation, we studied the regulation of the leukocyte-type 12-lipoxygenase of murine peritoneal macrophages by interleukins and found that the activity of this enzyme is upregulated in a dose-dependent manner when the cells were cultured in the presence of the IL-4 or IL-13 but not by IL-10. When peripheral murine monocytes that do not express the lipoxygenase were treated with IL-4 expression of 12/15-lipoxygenase mRNA was induced, suggesting pretranslational control mechanisms. In contrast, no upregulation of the lipoxygenase activity was observed when the macrophages were prepared from homozygous STAT6-deficient mice. Peritoneal macrophages of transgenic mice that systemically overexpress IL-4 exhibited a threefold to fourfold higher 12-lipoxygenase activity than cells prepared from control animals. A similar upregulation of 12-lipoxygenase activity was detected in heart, spleen, and lung of the transgenic animals. Moreover, a strong induction of the enzyme was observed in red cells during experimental anemia in mice. The data presented here indicate that (1) the 12-lipoxygenase activity of murine macrophages is upregulated in vitro and in vivo by IL-4 and/or IL-13, (2) this upregulation requires expression of the transcription factor STAT6, and (3) the constitutive expression of the enzyme appears to be STAT6 independent. The cytokine-dependent upregulation of the murine macrophage 12-lipoxygenase and its induction during experimental anemia suggests its close relatedness with the human reticulocyte-type 15-lipoxygenase despite their differences in the positional specificity of arachidonic acid oxygenation.

LIPOXYGENASES (LOXs) constitute a family of lipid peroxidizing enzymes that catalyze the oxygenation of polyunsaturated fatty acids to their corresponding hydroperoxy derivatives.1,2 According to the currently used nomenclature, these enzymes are classified according to their reaction specificity of arachidonic acid oxygenation.1-3 5-LOXs oxygenate arachidonic acid at C5 of the fatty acid backbone, whereas 12-and 15-lipoxygenases introduce molecular dioxygen at C12 and C15, respectively. This arachidonic acid–related nomenclature suffers from several disadvantages, which may lead to confusion among scientists not working in the field. One of these problems is the diversity of arachidonate 12- and 15-LOXs. The platelet-type 12-LOX strongly differs from the leukocyte-type 12-LOX with respect to its protein chemical and enzymatic properties.1,4 Similarly, the human epidermis-type 15-LOX5 is different from the reticulocyte-type 15-LOX of the same species.6,7 On the other hand, the murine,8 porcine,9 and bovine10leukocyte-type 12-LOXs share a high degree of structural homology with the reticulocyte-type 15-LOX of rabbits and humans, suggesting that the leukocyte-type 12-LOXs of mouse, pig, and cattle may be functionally related to the reticulocyte-type 15-LOXs of other species.

5-LOXs play a major role in the biosynthesis of leukotrienes, which are important mediators of anaphylactic and inflammatory diseases.11,12 In contrast, the physiological importance of 12-and 15-LOXs is not as well-investigated. In rabbit reticulocytes the 15-LOX was implicated in the maturational breakdown of mitochondria during red-cell development.13 The high-level expression of the enzyme in mature macrophages14 and its absence in the precursor monocytes15 suggests a role in monocyte/macrophage transition or in macrophage function. Recently, 15-LOXs have been implicated in atherogenesis because of their capability of oxidizing low-density lipoprotein to an atherogenic form.16

The expression of 15-LOX in mammalian cells is highly regulated.17 In rabbit reticulocytes a 15-LOX mRNA binding protein (15-LOX-BP) has been identified18,19 that binds to a characteristic repetitive motif in the 3′-untranslated region of the 15-LOX mRNA,17,20 preventing its translation. In human peripheral monocytes16,21 and alveolar macrophages15 the enzyme is upregulated when the cells were cultured in vitro in the presence of interleukin-4 (IL-4) or IL-13. Other cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-2, IL-3, and IL-10 were ineffective.16 A similar cytokine-dependent 15-LOX induction was recently observed in the human lung carcinoma cell line A549 but was not detected in various human and murine monocytic cell lines.22 Because the induction was shown by Northern blot analysis, by immunoblotting, and by activity assays, pretranslational control mechanisms are involved. In mouse peritoneal macrophages a linoleic acid ω-6 lipoxygenase activity has been described that was also upregulated by IL-4.23

Although the IL-4– and IL-13–induced signal transduction cascades have been studied in detail in several cells,24-26 the mechanism of cytokine-induced 15-LOX expression is not well understood. Experiments with IL-4 receptor antagonists suggested that the IL-4 and/or IL-13 cell surface receptor(s) appear to be involved.22 However, almost nothing is known about the intracellular events leading to expression of the 15-LOX in any cellular system. Moreover, there is no experimental evidence suggesting that IL-4–induced upregulation of 12-/15-LOXs does actually occur in vivo.

To address this questions and to obtain more detailed information on the mechanism of cytokine-induced LOX expression, peritoneal macrophages and peripheral monocytes were prepared from normal mice and from genetically modified animals, and the impact of cytokine stimulation on the 12/15-LOX activity was measured. The data obtained suggest that IL-4 upregulates the activity of the murine leukocyte-type 12-LOX in vitro and in vivo. Moreover, we found that IL-4– and IL-13–induced upregulation requires the expression of STAT6 transcription factor. However, the constitutive background activity of the enzyme appears to be STAT6 independent.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

The chemicals used were purchased from the following vendors: recombinant murine and human interleukins-4, -10, and -13 from R&D Systems GmbH (Wiesbaden, Germany); cell culture media from GIBCO-BRL (Eggenstein, Germany); methanol, n-hexane, and 2-propanol (HPLC pure) from Baker (Gross-Gerau, Germany); and authentic standards of 12S-, 12R-, 15S-, and 15R-HETE and arachidonic acid from Cayman Chem (Ann Arbor, MI).

Animal experiments.

STAT6 deficient mice (−/−) were produced and maintained as described previously.27 For knocking out the STAT6 gene, clones from a 129/SvE genomic library were injected into C57BL/6 blastocytes. All mice were 129/C57 Black mixtures, and age-matched female individuals of STAT6-deficient mice and controls with comparable genetic background were used for the experiments. IL-4–overexpressing transgenic mice28 29 as well as the corresponding inbred controls were kindly provided by Dr A. Schimpl (Würzburg, Germany).

Experimental anemia was induced in mice by repeated subcutaneous injection of a neutralized phenylhydracine solution. The mice were killed by diethyl ether inhalation and blood was removed from the Vena cava inferior. The cells were spun down and washed twice with isotonic saline, and 0.1 mL of packed cells were resuspended in 1 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Arachidonic acid oxygenase activity was assayed as described for peritoneal macrophages (see below).

Cell preparation and culturing conditions.

Mice were killed by carbon dioxide or diethyl ether inhalation. Peritoneal macrophages were prepared by peritoneal lavage with 10 mL of sterile PBS. The cells were spun down, washed once with sterile PBS, resuspended in Dulbecco's minimal essential medium (DMEM) containing penicillin/streptomycin and 10% fetal calf serum and plated to 6-well culture dishes or normal Petri-dishes at a concentration of about 1 × 106 cells/well. The macrophages were allowed to adhere to the dishes (2 to 3 hours), the nonadherent cells were removed, and the cells were kept in culture for up to 96 hours. Fluorescence-associated cell sorting analysis of the adherent cells indicated that more than 80% of the cells were stained positive for the macrophage surface antigen CD11b. The culture medium was changed after 24 and 76 hours. Interleukins were added to the culture medium after the cells were kept in culture for 24 hours. After different times the cells were detached by trypsination for 10 minutes (addition of 2 mL trypsin/versene solution; BioWitthaker,Verviers, Belgium) or by scraping them from the dishes. Then the cells were washed once with PBS and resuspended in 1 mL of PBS. Murine peripheral monocytes were prepared from whole blood by density step-gradient centrifugation and adherence to plastic dishes as described for human monocytes.15 For the experiments heparin-blood of 20 mice was combined. Murine alveolar macrophages were obtained by broncho-alveolar lavage with three 1-mL rinses of PBS. The cell suspensions were combined and the cells were washed with PBS and were further treated as described above for the peritoneal macrophages.

LOX activity assay.

Arachidonic acid (final concentration of 20 μmol/L or 100 μmol/L) was added as LOX substrate to the cell suspension as methanolic stock solution, and either the intact cells or a cell homogenate (sonication with a microtip sonifier [Brown AG, Melsungen, Germany]) were incubated with the substrate for 15 minutes at 37°C. The samples were acidified to pH 3, and the lipids were extracted with an equal volume of ethylacetate or with a 2:1 (vol/vol) mixture of methanol/chloroform. After centrifugation, the organic phase containing the lipophilic LOX products was recovered, the solvent was evaporated under vacuum, and the remaining lipids were reconstituted in 0.1 mL of methanol. Aliquots (usually half of the sample) were injected to reverse-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) for quantification of the LOX products.

HPLC analysis.

HPLC was performed on a Waters (Eschborn, Germany) or a Shimadzu (Kyoto, Japan) HPLC system connected to diode array detectors. If not stated otherwise, RP-HPLC was performed on Nucleosil C-18 column (Macherey/Nagel, Düren, Germany; KS-system, 250 × 4 mm, 5 μm particle size). The analytes were eluted isocratically with the solvent system methanol/water/acetic acid (85/15/0.1; by volume) at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The absorbance at 235 nm was recorded. The chromatograms were quantified by peak area, and a calibration curve (six-point calibration) for 12-HETE was established. The fractions containing the LOX products were collected, and the solvent was evaporated. The lipids were reconstituted in 0.2 mL of n-hexane, and aliquots were injected to straight-phase (SP)-HPLC and/or chiral-phase HPLC. SP-HPLC was performed on a Nucleosil column (Macherey/Nagel; KS-system, 250 × 4 mm, 10 μm particle size) with a solvent system of n-hexane/2-propanol/acetic acid (100/2/0.1; by volume) and a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The hydroxy fatty acid enantiomers were separated on a Chiralcel-OD column (Baker, Germany) using the solvent systems n-hexane/2-propanol/acetic acid (100:5:0.1; by volume) for 15-HETE and n-hexane/2-propanol/acetic acid (100:3:0.1; by volume) for 12-HETE. The chemical structures of the hydroxy fatty acid isomers were identified by ultraviolet spectroscopy, by coinjections with authentic standards in RP- and SP-HPLC, and by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS).

Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR).

Total RNA was prepared by guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction and was stored as ethanol precipitates at −20°C. The cDNAs were obtained by reverse-transcription using the avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase (AMV-RT) and oligo(dT) as primer. PCR was performed on a Biometra TRIO Thermoblock 2.51BB (Biometra, Göttingen, Germany). Total RNA (3 μg) was reverse transcribed at 37°C for 90 minutes in 45 μL of 50 mmol/L Tris/HCl buffer, pH 8.2, containing 8 mmol/L MgCl2, 30 mmol/L KCl, 1 mmol/L DTT, 100 μg/mL bovine serum albumin, 30 U of RNase inhibitor, 0.166 mmol/L of each dNTP, 150 pmol of oligo(dT) primer, and 15 U of reverse transcriptase. To stop the reaction samples were heated to 95°C for 10 minutes. For quantification the mRNA of the murine 12/15-LOX was related to the glycerolaldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mRNA. As housekeeping enzyme, the GAPDH mRNA may not be regulated by cytokines. For amplification of the 12/15-LOX and of the GAPDH the following primer combinations were used: 5′-CTC CCT GTA GAC CAG CGA TTT CGA -3′ and 5′-GGC AGT TCG AGC TGG ATG GCT ATA (12/15-LOX; expecting a 484-bp fragment) and 5′-TCG GTG TGA ACG GAT TTG GCC GTA-3′ and 5′-ATG GAC TGT GGT CAT GAG CCC TTC-3′ (GAPDH, expecting a 521-bp fragment). For positive controls the cDNA of the murine leukocyte type 12-LOX was used. Two microliters of the reverse transcriptase reaction were used for amplification, and the PCR mixture consisted of a 10-mmol/L Tris/HCl buffer, pH 8.3, containing 50 mmol/L KCl, 2 mmol/L MgCl2, 6 pmol of primer sets, 0.1 mmol/L of each dNTP, and 2.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase. After initial denaturation for 4 minutes at 94°C, 30 cycles of PCR were performed. Each cycle consisted of a denaturing period (40 seconds at 94°C), an annealing phase (60 seconds at 65°C for 15-LOX or 69°C for GAPDH) and an extension period (120 seconds at 72°C). After the last cycle, all samples were incubated for additional 10 minutes at 72°C. PCR products were separated by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis, the DNA was stained with ethidium bromide, and the electropherograms were quantified densitometrically. For quantification the intensities of the GAPDH bands was set 100% for each, IL-4–treated and –untreated cells.

RESULTS

The activity of the leukocyte-type 12-LOX of murine peritoneal macrophages is upregulated in vitro by IL-4 and IL-13.

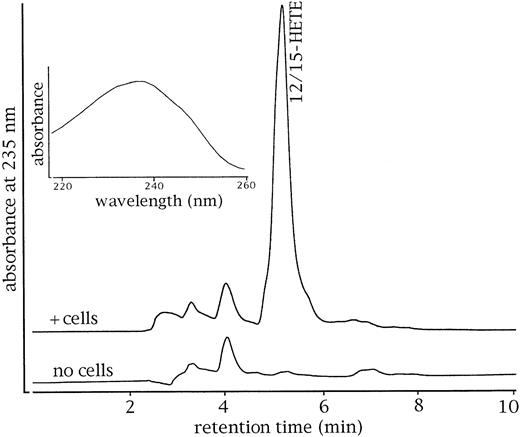

The expression of the reticulocyte-type 15-LOX of human peripheral monocytes16, 21 and of alveolar macrophages15is induced when the cells were cultured in vitro in the presence of IL-4 and/or IL—13. We analyzed the 12/15-LOX activity of murine peritoneal lavage cells (Fig 1, upper trace) and found that a cell lysate converted exogenous arachidonic acid to products comigrating in RP-HPLC with authentic standards of (5Z,8Z,10E,14Z)-12S-hydroxyeicosa-5,8,10,14-tetraenoic acid (12S-HETE) and (5Z,8Z,11Z,13E)-15S-hydroxyeicosa-5,8,11, 13-tetraenoic acid (15S-HETE). Similar products were formed with intact cells, but the extent of product formation was somewhat lower (data not shown). The products contained a characteristic conjugated diene chromophore with an absorbance maximum at 236 nm (inset). Because under these chromatographic conditions the different positional HETE isomers were not well-resolved, SP-HPLC was performed to confirm the chemical structures. This analytical procedure indicated a 8:1 mixture of 12-HETE and 15-HETE. In this particular experiment, 0.98 μg 12/15-HETE per 106 cells was formed within a 15-minute incubation period. In the corresponding control incubation (no cells), very small amounts of oxygenated fatty acids were detected (Fig 1, lower trace). Formation of 12-and 15-HETE was completely inhibited by the LOX inhibitor 5,8,11,14-eicosatetraynoic acid but was not affected by the cyclooxygenase inhibitor indomethacin (data not shown). When linoleic acid was used as substrate, (9Z,11E)-13S-hydroxyoctadeca-9,11-dienoic acid (13S-HODE) was identified as major oxygenation product (data not shown).

Murine peritoneal lavage cells express an arachidonate 12-LOX. Peritoneal lavage in mice was performed as described in Material and Methods. The cells were spun down, washed, and resuspended in 1 mL of PBS. After addition of arachidonic acid (100 μmol/L final concentration), the cells were disrupted and the lysate was incubated for 15 minutes at 37°C. The reaction was stopped by acidification to pH 3, and the lipids were extracted with 1 mL of ethylacetate. The solvent was evaporated, the remaining lipids were reconstituted in 200 μL of methanol, and aliquots were analyzed by RP-HPLC as described in Materials and Methods. Upper trace, incubation with cells; lower trace, control incubation (no cells). Cells alone do not contain significant amounts of hydroxy fatty acids. Inset, ultraviolet-spectrum of the hydroxy fatty acids indicating the presence of conjugated dienes.

Murine peritoneal lavage cells express an arachidonate 12-LOX. Peritoneal lavage in mice was performed as described in Material and Methods. The cells were spun down, washed, and resuspended in 1 mL of PBS. After addition of arachidonic acid (100 μmol/L final concentration), the cells were disrupted and the lysate was incubated for 15 minutes at 37°C. The reaction was stopped by acidification to pH 3, and the lipids were extracted with 1 mL of ethylacetate. The solvent was evaporated, the remaining lipids were reconstituted in 200 μL of methanol, and aliquots were analyzed by RP-HPLC as described in Materials and Methods. Upper trace, incubation with cells; lower trace, control incubation (no cells). Cells alone do not contain significant amounts of hydroxy fatty acids. Inset, ultraviolet-spectrum of the hydroxy fatty acids indicating the presence of conjugated dienes.

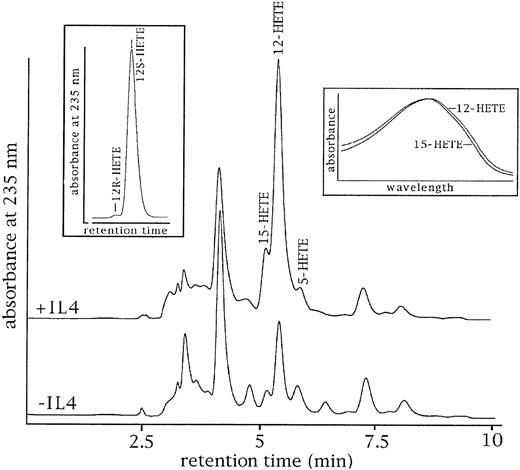

Peritoneal macrophages that were cultured for 4 days in the presence of 0.8 nmol/L IL-4 (Fig 2, upper trace) produce more 12/15-HETE than cells cultured in the absence of the cytokine (lower trace). In this particular experiment, a fourfold increase in 12/15-HETE formation was observed, whereas 5-HETE formation remained unchanged. The ultraviolet-spectra (right inset) of the major conjugated dienes formed (12-HETE and 15-HETE) were similar in shape but were slightly different with respect to their λmax-values. For the early eluting peak of 15-HETE a λmax of 235 nm was determined, whereas maximal absorption for the late eluting 12-HETE was at 236 nm.30 Analysis of the enantiomer composition of 12-HETE (left inset) indicated a preponderance of the S-isomer, suggesting that the compound was formed via LOX pathway.

Upregulation of murine macrophage 12-lipoxygenase activity by IL-4. Murine peritoneal macrophages were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. After adhesion to plastic dishes they were cultured for 4 days in the absence (lower trace) or presence (upper trace) of IL-4 (0.8 nmol/L final concentration). Cells were obtained, and cell homogenates were incubated with arachidonic acid (100 μmol/L final concentration). Product preparation and RP-HPLC as described in the legend to Fig 1. Left inset, enantiomer analysis (chiral phase HPLC) of 12-HETE prepared by RP-HPLC; right inset, ultraviolet-spectra of the products coeluting with 12- and 15-HETE. In some experiments the ulraviolet-spectrum of the products coeluting with 15-HETE did show an absorbance at 280 nm, which may be due to the formation of conjugated ketodienes.

Upregulation of murine macrophage 12-lipoxygenase activity by IL-4. Murine peritoneal macrophages were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. After adhesion to plastic dishes they were cultured for 4 days in the absence (lower trace) or presence (upper trace) of IL-4 (0.8 nmol/L final concentration). Cells were obtained, and cell homogenates were incubated with arachidonic acid (100 μmol/L final concentration). Product preparation and RP-HPLC as described in the legend to Fig 1. Left inset, enantiomer analysis (chiral phase HPLC) of 12-HETE prepared by RP-HPLC; right inset, ultraviolet-spectra of the products coeluting with 12- and 15-HETE. In some experiments the ulraviolet-spectrum of the products coeluting with 15-HETE did show an absorbance at 280 nm, which may be due to the formation of conjugated ketodienes.

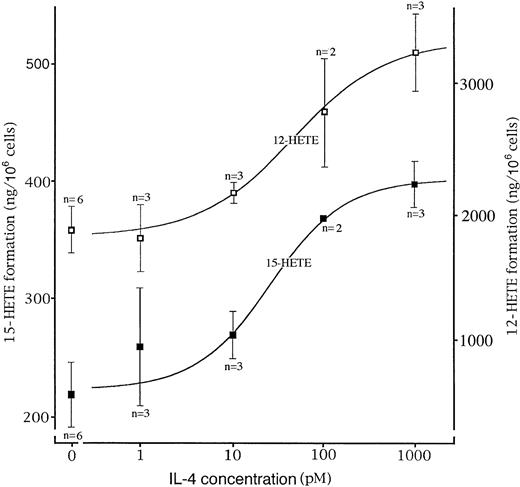

From Fig 3 it can be seen that the extent of upregulation of the 12/15-LOX activity did depend on the IL-4 concentration. A tendency of activation was already seen at 1 and 10 pmol/L, but significant upregulation was observed at IL-4 concentrations of 100 pmol/L and higher. It should be mentioned that the 12-HETE/15-HETE ratio was about 10:1 over the entire concentration range. For the human 15-LOX it has been shown that the enzyme is induced by IL-4 and IL-13, whereas other cytokines, such as IL-10, had no effects. From Table 1 it can be seen that the murine macrophage 12/15-LOX exhibits a similar cytokine responsiveness.

Dose-response curve of 12- and 15-HETE formation by murine peritoneal macrophages on IL-4 concentration. Peritoneal lavage cells were prepared from 30 mice by rinsing the peritoneal cavity of each mouse with 10 mL of PBS. The lavage fluid was pooled, the cells were washed once, plated in 6-well plates, and the macrophages were allowed to adhere overnight. After removing nonadherent cells, different concentrations of IL-4 were adjusted and the cells were kept in culture for additional 3 days. For most IL-4 concentrations, three separate wells were used. After 3 days the cells from each well were obtained separately and the arachidonic acid oxygenase activity was determined. 12- and 15-HETE formation was quantified by RP-HPLC. The n-numbers above the traces indicate how many wells were used for one IL-4 concentration, and the arrow bars represent the standard deviation. At 100 pmol/L of IL-4 we measured exactly the same 15-HETE formation in both HPLC runs. Thus, no arrow bar can be given.

Dose-response curve of 12- and 15-HETE formation by murine peritoneal macrophages on IL-4 concentration. Peritoneal lavage cells were prepared from 30 mice by rinsing the peritoneal cavity of each mouse with 10 mL of PBS. The lavage fluid was pooled, the cells were washed once, plated in 6-well plates, and the macrophages were allowed to adhere overnight. After removing nonadherent cells, different concentrations of IL-4 were adjusted and the cells were kept in culture for additional 3 days. For most IL-4 concentrations, three separate wells were used. After 3 days the cells from each well were obtained separately and the arachidonic acid oxygenase activity was determined. 12- and 15-HETE formation was quantified by RP-HPLC. The n-numbers above the traces indicate how many wells were used for one IL-4 concentration, and the arrow bars represent the standard deviation. At 100 pmol/L of IL-4 we measured exactly the same 15-HETE formation in both HPLC runs. Thus, no arrow bar can be given.

Induction of the Murine Macrophage 12-Lipoxygenase by Selected Cytokines

| No. . | Mice . | Cytokine . | n . | 12/15-HETE Formation-150 (μg/106 cells) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | NMRI | no (control) | 6 | 2.13 ± 0.25 |

| IL-4 | 3 | 3.67 ± 0.30 | ||

| IL-10 | 3 | 2.18 ± 0.18 | ||

| 2 | STAT6(+/+) controls | no (control) | 4 | 11.3 ± 1.7 |

| IL-4 | 4 | 18.7 ± 1.9 | ||

| IL-13 | 4 | 17.8 ± 0.7 | ||

| STAT6(−/−) | no (control) | 4 | 10.2 ± 2.3 | |

| IL-4 | 4 | 5.5 ± 1.5 | ||

| IL-13 | 4 | 3.0 ± 0.2 |

| No. . | Mice . | Cytokine . | n . | 12/15-HETE Formation-150 (μg/106 cells) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | NMRI | no (control) | 6 | 2.13 ± 0.25 |

| IL-4 | 3 | 3.67 ± 0.30 | ||

| IL-10 | 3 | 2.18 ± 0.18 | ||

| 2 | STAT6(+/+) controls | no (control) | 4 | 11.3 ± 1.7 |

| IL-4 | 4 | 18.7 ± 1.9 | ||

| IL-13 | 4 | 17.8 ± 0.7 | ||

| STAT6(−/−) | no (control) | 4 | 10.2 ± 2.3 | |

| IL-4 | 4 | 5.5 ± 1.5 | ||

| IL-13 | 4 | 3.0 ± 0.2 |

Murine peritoneal macrophages were prepared from normal mice (experiment 1), from homozygous STAT6 deficient animals (experiment 2), and from inbred control mice (experiment 2) by peritoneal lavage and adherence to plastic dishes (see Materials and Methods). The cells were cultured in the presence or absence of cytokines (1 nmol/L) at 37°C, scraped from the dishes after 4 days, and sonicated in the presence arachidonic acid. After incubation for 15 minutes at 37°C, the lipids were extracted and the lipoxygenase products were quantified by RP-HPLC (see Materials and Methods). For experiment 1, male NMRI mice were used, and a final arachidonic acid concentration of 30 μmol/L was adjusted. For experiment 2 STAT6-deficient mice and the corresponding inbred controls were used. Here the arachidonic acid concentration was 0.1 mmol/L.

Mean ± SD.

To find out whether the upregulation of 12/15-LOX activity is paralelled by an increase in the steady-state concentration of the 12/15-LOX protein, immunohistochemical stainings were performed. We found that both IL-4–treated and –untreated peritoneal macrophages were stained 12/15-LOX positive. Although the staining appeared to be somewhat more intense with the IL-4–treated cells, exact quantification was not possible.

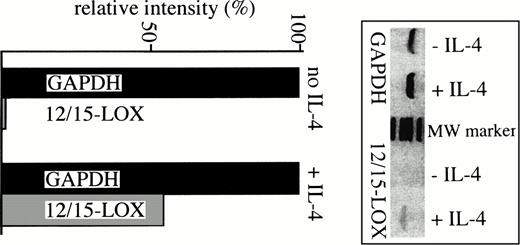

The experiments with murine peritoneal macrophages were hampered by the fact that these cells constitutively express the 12/15-LOX at a fairly high level. To avoid this problem we prepared peripheral monocytes from mice and cultured these cells for 4 days in the absence and presence of IL-4. Because the number of cells obtained (5 × 105monocytes) was not sufficient for activity assays, we performed RT-PCR to quantify 12/15-LOX mRNA expression. From Fig 4 it can be seen that no 12/15-LOX mRNA is expressed in peripheral monocytes cultured for 4 days in the absence of IL-4. However, when IL-4 was present in the culture medium, a LOX positive band was detected. These data suggest that in murine monocytes 12/15-LOX expression is upregulated by IL-4 and that pretranslational mechanisms appear to be involved.

Upregulation of 12/15-LOX mRNA expression in murine peripheral monocytes by IL-4. The blood of 20 mice was pooled, and the white blood cells were prepared by density step-gradient centrifugation.15 After washing twice with PBS, the cells were plated to Petri-dishes and macrophages were allowed to adhere overnight. Nonadherent cells (mainly granulocytes and lymphocytes) were removed by washing the plates five times with culture medium. The adherent cells were scraped off the plates and were resuspended in 0.2 mL of PBS. Total RNA and RT-PCR of the GAPDH and 12/15-LOX mRNA were performed as described in Material and Methods. For quantification (lower part of the figure) the intensity of the GAPDH band obtained from IL-4–treated cells was set 100% and the intensity of the other bands were related to it. Inset, original PCR pattern obtained from the different samples.

Upregulation of 12/15-LOX mRNA expression in murine peripheral monocytes by IL-4. The blood of 20 mice was pooled, and the white blood cells were prepared by density step-gradient centrifugation.15 After washing twice with PBS, the cells were plated to Petri-dishes and macrophages were allowed to adhere overnight. Nonadherent cells (mainly granulocytes and lymphocytes) were removed by washing the plates five times with culture medium. The adherent cells were scraped off the plates and were resuspended in 0.2 mL of PBS. Total RNA and RT-PCR of the GAPDH and 12/15-LOX mRNA were performed as described in Material and Methods. For quantification (lower part of the figure) the intensity of the GAPDH band obtained from IL-4–treated cells was set 100% and the intensity of the other bands were related to it. Inset, original PCR pattern obtained from the different samples.

In vivo upregulation of murine 12-LOX by systemic overexpression of IL-4.

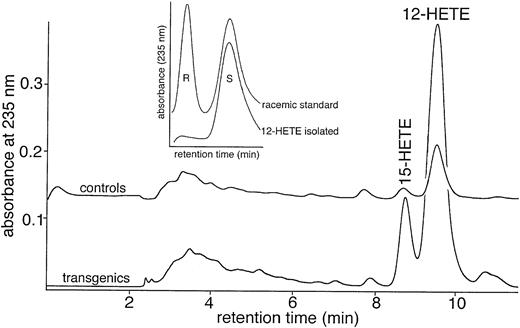

So far the IL-4– and IL-13–induced upregulation of the human 15-LOX has only been shown under in vitro conditions.14,15,21,22To find out whether this effect may actually occur in vivo we prepared peritoneal macrophages from transgenic mice that overexpress IL-4 under the control of major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-I regulatory sequences.28 From Fig 5 it can be seen that the macrophages of transgenic mice exhibit a threefold to fourfold higher 12-LOX activity than cells prepared from the corresponding control animals. Statistic evaluation of the data obtained from 10 individuals gave the following results: transgenics (n = 5), 12-LOX activity of 9.73 ± 1.88 μg HETE/106 cells (mean ± SD); controls, 2.84 ± 0.88 μg HETE/106 cells (mean ± SD), P = .005. It should be stressed that the pattern of arachidonic acid oxygenation products, in particular the 15-HETE/12-HETE-ratio (about 1:5), was comparable for the transgenic mice and the control animals, suggesting that these products are formed by the same enzyme. Enantiomer analysis of the major product of arachidonic acid oxygenation, 12-HETE, showed a strong preponderance of the S-isomer, indicating the 12-LOX origin. These data suggest that the increased arachidonic acid oxygenating capability of the peritoneal macrophages prepared from IL-4–overexpressing mice is due to an upregulation of the 12-LOX activity. In additional experiments we addressed the question whether the upregulation of the LOX activity was restricted to macrophages or whether an increase in enzyme activity can also be detected in other tissues. We found that HETE formation from exogenous arachidonic acid was augmented in the spleen (47 μg HETE/g wet weight v 19 μg HETE/g wet weight in a control animal), the lung (42 μg HETE/g wet weight v 20 μg HETE/g wet weight in a control animal), and the heart (15 μg HETE/g wet weight v 7 μg HETE/g wet weight in a control animal) of the transgenic animals. In contrast, arachidonic acid oxygenase activity was not altered in liver (22 μg HETE/g wet weight v 24 μg HETE/g wet weight in a control animal) and skeleton muscle (17 μg HETE/g wet weight v 18 μg HETE/g wet weight in a control animal).

Peritoneal macrophages of IL-4–overexpressing mice exhibit a higher 12/15-LOX activity than cells prepared from control animals. Peritoneal lavage cells were prepared from IL-4–overexpressing mice (n = 5) and from corresponding control animals (n = 5). The lavage fluid of two animals was combined, the cells were washed twice with PBS, plated to Petri-dishes, and the macrophages were allowed to adhere overnight. After removal of nonadherent cells, the macrophages were scraped from the dishes and a cell homogenate was incubated in the presence of 100 μmol/L of arachidonic acid for 15 minutes at 37°C. Lipid extraction and RP-HPLC analysis of the LOX products was performed as described in Material and Methods. A representative RP-HPLC chromatogram is shown. The 12-HETE formed was purified by RP-HPLC and was further analyzed for its enantiomer composition by CP-HPLC (inset).

Peritoneal macrophages of IL-4–overexpressing mice exhibit a higher 12/15-LOX activity than cells prepared from control animals. Peritoneal lavage cells were prepared from IL-4–overexpressing mice (n = 5) and from corresponding control animals (n = 5). The lavage fluid of two animals was combined, the cells were washed twice with PBS, plated to Petri-dishes, and the macrophages were allowed to adhere overnight. After removal of nonadherent cells, the macrophages were scraped from the dishes and a cell homogenate was incubated in the presence of 100 μmol/L of arachidonic acid for 15 minutes at 37°C. Lipid extraction and RP-HPLC analysis of the LOX products was performed as described in Material and Methods. A representative RP-HPLC chromatogram is shown. The 12-HETE formed was purified by RP-HPLC and was further analyzed for its enantiomer composition by CP-HPLC (inset).

Involvement of STAT6 in IL-4–induced upregulation of 12-LOX activity.

The mechanism of IL-4–dependent upregulation of LOXs, in particular the steps of the cytokine-induced signal transduction cascade necessary for this upregulation, has not been investigated so far. In various cellular systems IL-4–mediated effects involve activation of the transcription factor STAT6. In its phosphorylated form STAT6 binds to STAT6-responsive elements in the promoter region of IL-4–sensitive genes and turns on their transcription. We screened the promoter sequences of various mammalian LOXs (rabbit 15-LOX,31 human 15-LOX,32 murine leukocyte-type 12-LOX,8porcine leukocyte-type 12-LOX,33 human 5-LOX,34platelet-type 12-LOX,35 murine platelet-type 12-LOX8) for the presence of STAT6-responsive elements with the consensus sequence TTC NNN(N) GAA36 and found potential STAT6-binding sites in the promoter of the rabbit and human 15-LOX genes and in the genes coding for the murine and porcine leukocyte-type 12-LOXs. In contrast, the promoters of the murine platelet 12-LOX8 and of the human 5-LOX34 do not contain potential STAT6-binding elements. To find out whether STAT6 is involved in the IL-4–induced signal transduction cascade leading to the upregulation of 15-LOX activity, experiments with STAT6 deficient mice were performed. From the data shown in Table 1 (lower part) the following conclusions may be drawn. First, the 12-LOX activity of peritoneal macrophages prepared from control mice was increased by about 60% when the cells were cultured in the presence of IL-4 or IL-13. Second, when the macrophages were prepared from STAT6-deficient mice, the 12-LOX activity was not augmented. In contrast, we observed a significant decrease in LOX activity after culturing the cells in the presence of IL-4 or IL-13. The mechanistic reasons for this impaired LOX activity in the STAT6-deficient macrophages remain unclear. It might be possible that such an inhibitory effect does also occur in the macrophages of normal mice. However, owing to the STAT6-dependent upregulation of 12-LOX activity, the inhibitory effect may be masked. Finally, the level of constitutive expression of the 12-LOX (no cytokine treatment) in the STAT6-deficient mice was comparable with that of the control animals. These data suggest that IL-4– and IL-13–induced upregulation of 12/15-LOX activity requires the expression of STAT6, whereas the constitutive background expression of the enzyme does not involve this transcription factor.

Upregulation of 12/15-LOX activity during experimental anemia.

The expression of the 15-LOX in rabbit reticulocytes is strongly induced during the time course of an experimental anemia.37To obtain additional evidence for the relatedness of the rabbit 15-LOX and the murine 12/15-LOX, we induced an experimental anemia in mice and assayed the LOX activity in red blood cells. From Table 2 it can be seen that no 12/15-LOX was present in erythrocytes of untreated mice. In contrast, when the animals were treated with phenylhydracine to induce an experimental anemia, the 12/15-LOX activity was strongly increased. Because this upregulation was also observed by RT-PCR and immunoblot analysis (data not shown), one may conclude that the murine 12/15-LOX shows a similar induction behavior as the rabbit 15-LOX and thus suggests a close relatedness of both enzymes.

Induction of 12/15-LOX Activity in Murine Red Blood Cells During Experimental Anemia

| Animals . | 12/15-LOX Activity (μg 12-HETE/mL red cells × 15 minutes) . | S/R Ratio of 12-HETE . |

|---|---|---|

| Control mice (no PH) | 0 | ND |

| Anemic mice (3.5 mg PH/kg) | 19.8 | 90:10 |

| Anemic mice (7 mg PH/kg) | 91.5 | >95:5 |

| Anemic mice (14 mg PH/kg) | 121.9 | >95:5 |

| Animals . | 12/15-LOX Activity (μg 12-HETE/mL red cells × 15 minutes) . | S/R Ratio of 12-HETE . |

|---|---|---|

| Control mice (no PH) | 0 | ND |

| Anemic mice (3.5 mg PH/kg) | 19.8 | 90:10 |

| Anemic mice (7 mg PH/kg) | 91.5 | >95:5 |

| Anemic mice (14 mg PH/kg) | 121.9 | >95:5 |

Female NMRI mice were injected a phenylhydracine (PH) solution subcutaneously at the dosage indicated in the table. The injection was repeated at 4 consecutive days, and development of reticulocytosis was followed by reticulocyte counting. The mice were allowed to recover for 3 days and were then sacrificed by diethylether inhalation. Blood was withdrawn from the V. cava inf., the cells were spun down and the buffy-coat containing the white cells, and platelets was removed. The red cells were washed with PBS, and 0.1 mL of packed cells were incubated with 0.1 mmol/L arachidonic acid for 15 minutes at 37°C. After lipid extraction the formation of 12- and 15-HETE was quantified by RP-HPLC.

Abbreviation: ND, not determined.

DISCUSSION

The leukocyte-type 12-LOX and the reticulocyte-type 15-LOX are expressed in various cells and tissues, but their biological role is still unclear. There are several suggestions for the biological importance of these enzymes, which may be categorized as follows:3 (1) formation of bioactive lipid mediators from free polyenoic fatty acids with potential importance for anaphylactic and inflammatory disease (in fact, 13-H(P)ODE and 15-H(P)ETE have been reported to exhibit proinflammatory and /or antiinflammatory activity in various cellular systems, in organ preparations, in whole animals, and in humans)38-41; and (2) direct oxygenation of lipid-protein assemblies, such as biomembranes and lipoproteins,42,43 leading to structural and functional alteration of these complexes, which may be of importance for cell development and atherogenesis.3 In rabbit reticulocytes the 15-LOX has been implicated in the maturational breakdown of mitochondria.13,14,37 If the leukocyte-type 12-LOX in mice were the functional equivalent of this enzyme, disruption of its gene should lead to problems with erythropoiesis. However, leukocyte-type 12-LOX–deficient mice do not have obvious abnormalities in hematopoiesis.44 Because of the diversity of the LOX family, these data do not necessarily mean that the leukocyte-type 12-LOX may not be involved in red cell maturation because disruption of its gene may be compensated by upregulation of a functionally related LOX. Although no reticulocyte-type 15-LOX has been cloned so far from mouse tissue, there is experimental evidence for the simultaneous expression of a leukocyte-type 12-LOX and a related reticulocyte-type 15-LOX in humans45 and in rabbits.46 If a similar LOX diversity would exist in mice, double or even multiple knockouts must be created.

The expression of the leukocyte-type 12-LOX and of the reticulocyte type 15-LOX in alveolar and peritoneal macrophages and their absence in the precursor monocytes suggested an involvement in monocyte-macrophage transition. This differentiation process is characterized inter alia by restructuring of the cellular membrane. For developing rabbit reticulocytes it has been shown that the 15-LOX oxygenates membrane lipids,47 and this enzymatic lipid peroxidation was implicated in red cell maturation.13 Moreover, an involvement of 12/15-LOXs in macrophage function was suggested.3,15 However, basic characterization of peritoneal macrophages isolated from 12-LOX–deficient mice did not reveal major dysfunction in macrophage maturation or macrophage physiology.44 It might be possible that defects in erythropoiesis or in macrophage function may appear when the animals are challenged in certain ways. Such experiments have not been performed so far.

With murine peritoneal macrophages we only observed a rather moderate, but statistically highly significant, increase in 12-LOX activity when the cells were exposed in vitro to IL-4. Summarizing our experiments, a twofold increase in the 12/15-LOX activity (2.1 ± 0.8-fold increase [mean ± SD], n = 9, P = .003) was found when murine peritoneal macrophages were cultured in the presence of 1 nmol/L IL-4 for 3 days. For human peripheral monocytes15, 21 and in A549 human lung carcinoma cells,22 a much stronger increase (10- to 20-fold) was described. This may primarily be due to the fact that mature macrophages show a high level of constitutive 12/15-LOX expression. In our hands, peripheral human monocytes exhibit a 15-LOX activity of less than 10 ng formation of 15-HETE/106 cells (15-minute incubation period). After stimulation with IL-4, up to 2 μg 15-HETE/106 cells was formed.22 Murine peritoneal macrophages exhibit a 12-LOX activity, which varied between 2 to 10 μg formation of 12-HETE/106 cells, and stimulation with IL-4 or IL-13 did only lead to a 0.5- to 4-fold increase. A similar rather moderate increase in LOX activity was observed when human alveolar macrophages, which also exhibit a high level constitutive 15-LOX expression, were stimulated with IL-4.14 Our RT-PCR studies in murine peripheral monocytes indicate that no 12/15-LOX is present in these cells but that the 12/15-LOX mRNA is expressed after IL-4 stimulation. Because the 12/15-LOX is expressed in murine peritoneal macrophages but cannot be detected in peripheral monocytes, the enzyme may be induced during monocyte/macrophage transition. Although this induction has now been shown in humans and mice, and might also occur in other animal species, its physiological relevance remains unclear.

The experiments with the STAT6-deficient mice provide evidence for an involvement of this STAT6 in IL-4–induced upregulation of 12/15-LOXs. Because the genes coding for leukocyte-type 12-LOXs and for the reticulocyte-type 15-LOX contain putative STAT6-binding sites, a direct interaction of STAT6 with these LOX genes appears possible. In contrast, the promoter regions of 5-LOX genes as well as of the genes coding for the platelet-type 12-LOXs do not contain putative STAT6-binding sequences. Because these LOXs subtypes strongly differ from the above mentioned enzymes with respect to their enzymatic and protein chemical properties, they may exhibit a different cytokine responsiveness. In fact, IL-4 treatment of human monocytes and A549 cells does neither induce the expression of the 5-LOX nor of the platelet-type 12-LOX.16,22 Although the existence of putative STAT6-binding sites in the promoter region of various LOX genes may point to a direct interaction of STAT6 with 12/15-LOX genes, kinetic studies on IL-4–induced 15-LOX expression in human monocytes16 and A549 lung carcinoma cells22suggested that the human 15-LOX gene may not belong to the family of immediate early genes turned on by IL-4. After stimulation of the cells with IL-4 it takes at least several hours before an increase in the 15-LOX activity and its mRNA can be measured. Thus, an indirect interaction of activated STAT6 with the human 15-LOX gene appears unlikely. It might be possible that stimulation of the cells with IL-4 leads to a STAT6-dependent synthesis of a protein, which in turn upregulates the expression of the 12-/15-LOX. In fact, at least in humans there are indications for the expression of such a regulatory protein.48

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We wish to thank C. Reuss for his expert technical assistance and Prof A. Schimpl (Würzburg) for kindly providing the IL-4 overexpressing mice and the corresponding control animals.

Supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Ku 961-2/2).

Address reprint requests to Hartmut Kühn, MD, DSc, Institute for Biochemistry, University Clinics (Charité), Humboldt University, Hessische Str 3-4, 10115 Berlin, FRG; e-mail:hartmut.kuehn@rz.hu-berlin.de.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked "advertisement" is accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal