Abstract

The purpose of this study was (1) to investigate the efficacy of chemotherapy regimens designed by the French Society of Pediatric Oncology for childhood anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (ALCL) and (2) to identify prognostic factors in these children. Eighty-two children with newly diagnosed ALCL were enrolled in two consecutive studies, HM89 and HM91. The diagnosis of ALCL was based on immuno-morphological features and all the cases but 2 were investigated using ALK1 antibody directed to the NPM/ALK protein associated with the 2;5 translocation. Treatment consisted of 2 courses of COPADM (methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) and a maintenance treatment of 5 to 7 months. Seventy-eight patients (95%) achieved a complete remission and 21 relapsed. The probability of survival and event-free survival at 3 years was of 83% (72% to 90%) and 66% (54% to 76%), respectively, with a median follow-up of 49 months. In multivariate analysis, visceral involvement, mediastinal involvement, and lacticodeshydrogenase (LDH) level ≥800 UI/L were shown to be predictive of a higher risk of failure. In conclusion, this type of regimen demonstrated efficacy in childhood ALCL. However, therapeutic results have to be improved for children with adverse prognostic parameters such as visceral or mediastinal involvement or a high LDH level.

THAT KI-1 ANAPLASTIC large-cell lymphoma (ALCL) is a distinct clinico-pathologic entity has been debated for several years, but its specific features are now well established1-3 and this entity has been included in both the updated Kiel classification4 and in the more recent Revised European-American lymphoma (REAL) classification.5This disease, covering most of the cases historically diagnosed as malignant histiocytosis6,7 and some cases of Hodgkin’s disease and other types of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, is characterized by the proliferation of neoplastic lymphoid cells coexpressing several activation antigens such as CD30 (Ki-1) and the epithelial membrane antigen (EMA).6 With respect to lymphocyte lineage markers, it is widely admitted that most of the cases are associated with a T-cell or null cell immunophenotype.5 The existence of sporadic cases of ALCL of the B-cell phenotype is still a debated question.

The t(2;5) (p23;q35) translocation, resulting in the fusion of the nucleophosmine gene (NPM) at 5q3 and the tyrosine kinase gene ALK at 2p23,8 was identified in this disease several years ago.9-11 However, the specificity of this translocation has not been established, because it has occasionally been reported in other lymphomas, especially in a few cases of large B-cell lymphomas and pleiomorphic T-cell lymphomas.12-16

This disease accounts for only 10% to 15% of all childhood non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas.17,18 Because it is rare, the optimal treatment has yet to be assessed. In most of the European studies, ALCL is considered as an entity and treated either with a short and intensive chemotherapy regimen, as in B-cell lymphoma,19 or with more prolonged chemotherapy derived from T-cell lymphoma protocols,20,21 whereas in the North American studies, all the large-cell lymphomas are treated with the same chemotherapy protocols regardless of the histologic subgroup and immunophenotype.22 23

Based on our previous experience of patients in whom disease was initially diagnosed as malignant histiocytosis and reviewed as ALCL and treated with COPAD (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone, doxorubicin) for first-line treatment and CCNU Bleomycin and vinblastine for relapse,24 prospective studies have been designed by the French Society of Pediatric Oncology (SFOP) for children with ALCL since 1988. We report here a series of 82 children enrolled in two consecutive SFOP studies (HM89 and HM91) between 1988 and 1997.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Diagnosis

The histopathologic material was reviewed by three pathologists (G.D., Z.M.B., and M.J.T.L.) for all of the patients included. The diagnosis of ALCL was based on the morphologic and immunologic criteria defined in the REAL classification for non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas5,25,26 and each case was assigned to one of the morphologic subtypes of ALCL previously described,26 except for 8 cases in which the biopsy specimen submitted for examination was too small. Immunohistochemistry was performed on routine sections and on frozen sections, when available, with a panel of monoclonal antibodies. All of the cases but 2 were investigated with the ALK1 antibody directed to the NPM/ALK protein associated with the t(2.5) translocation.27 In 10 cases from which no unstained material was available, labeling for ALK was performed on destained slides, as previously described.26 Other antibodies were obtained from DAKO A/S (Copenhagen, Denmark; CD3, CD45RO, CD20, anti-LMP1, and anti-EMA), Immunotech (Marseille, France; CD30 and CD15), Biotest (Buc, France; CD43 and MB2), Prof H. Stein (CD30/Ber-H2), and one of the authors’ (G.D.) laboratories (CD45RA, CD76, CD79a, CBF.78, and BNH.9).28,29 Immunostaining of paraffin sections was performed using the method described by Shi et al,30 with slight modifications.28 However, 12 cases had been studied several years earlier with a limited battery of antibodies and therefore could not be assigned to a precise phenotype. A cytogenetic analysis of the tumor was performed for 30 patients at diagnosis (28 patients) or at relapse (2 patients).

Inclusion

Between August 1988 and February 1997, 110 patients were treated according to the HM protocols. Twenty-eight cases (25.5%) were excluded from the analysis: 5 (4.5%) for previous treatment; 6 (5.5%) because slides were not available for re-examination; and 17 (15.5%), all ALK1−, because the diagnosis of ALCL was rejected after re-examination by the panel of pathologists. Seven of these cases, initially diagnosed as Hodgkin’s-like ALCL, were classified as Hodgkin’s disease rather than ALCL because of the phenotype of malignant cells (CD30+, CD15+, EMA−). Seven other cases were diagnosed as non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma other than ALCL (including 3 B-cell lymphoma), 1 as a histiocytic sarcoma, 1 as monoblastic leukemia, and 1 as a soft tissue sarcoma. Because central nervous system (CNS)-directed therapy was minimal in the chemotherapy schedule, patients with CNS involvement were excluded from the trial. During the same time period, 2 additional patients with CNS involvement were therefore not included in the study but (successfully) treated with the LMB86 protocol for B-cell lymphoma.31 The survival of the whole population, including the excluded cases that have also been studied, will be shown further on. Finally, 82 (median age, 10 years; range, 17 months to 17 years) cases were available for analysis. Twenty-six French centers and one Belgian center participated in these SFOP studies.

Approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board for these studies. Informed consent was provided according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Staging

The minimal investigations requested for staging were a physical examination, chest and nasopharyngeal x-rays, abdominal ultrasonography, a cranial computed tomography (CAT) scan, a complete blood count, two bone marrow aspirates, two bone marrow biopsies, examination of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), a skeletal scintigraphy, and lacticodeshydrogenase (LDH) level measurement. An LDH level exceeding 800 UI/L, which is twofold the upper limit of the normal level in 70% of the centers, was considered pathologic.

Staging was performed according to the St Jude’s classification32 and according to the Ann Arbor staging systems for Hodgkin’s disease.33 Histological evidence was not required for the diagnosis of organ or skin involvement. Patients with skin lesions were considered as having stage IV disease according to the Ann Arbor classification.

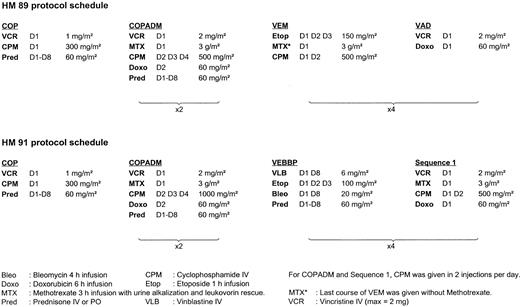

Chemotherapy Regimen

Between August 1988 and December 1990, 18 patients were treated according to the HM 89 protocol; between January 1991 and February 1997, 64 patients were treated according to the HM 91 protocol. The schedules of these two protocols are detailed in Fig 1. Within each protocol, all patients received the same treatment whatever the stage, because the prognostic value of the stage had not been clearly demonstrated in the historical series of patients treated by COPAD.24 The total duration of the treatment was 8 months for HM89 and 7 months for HM91. No intrathecal therapy was administered either in HM89 or in HM91.

Response Criteria

Complete remission (CR) was defined as the disappearance for at least 4 weeks of all tumor masses confirmed by clinical examination, x-rays, ultrasonography, and a normal bone marrow. A chest computerized tomography (CT) scan was not required to confirm remission of mediastinal or lung lesions. Any tumor residue detectable after the third course of induction therapy had to be removed surgically or the minimum requirement was a biopsy specimen. CR was confirmed only in the absence of tumor cells.

Statistical Analysis

Overall survival rates were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method34 from the first day of chemotherapy to death or to the date of the last follow-up visit for patients who were still alive. Event-free survival (EFS) rates were estimated from the first day of chemotherapy to the time of documented failure (date of the beginning of treatment for patients whose disease progressed while they were on chemotherapy before achieving a CR, time of relapse, or time of death for the others) or to the date of the last follow-up visit for those in first CR. Follow-up data were updated as of June 1, 1997. Statistical differences in EFS were tested by the two-tail log-rank test, adjusted on the chemotherapy protocol.

Cox regression modeling35 was performed using the BMDP 2L program,36 with a backward procedure. Variables to be included or removed in the model were selected at each step, using the MPLR method, with a P value equal to .10 for items to be entered and P value of .05 for items removed. All of the clinical variables selected by univariate analysis (P < .20) were entered at the first step of the model adjusted on the chemotherapy protocol. Because of missing data, biological variables (ie, LDH, histologic subtype, and immunophenotype) were not entered together in the first model. Each biological variable has been tested separately in the clinical model. Relative risks (RR) are given with their 95% confidence intervals. The median follow-up was estimated using the Schemper method.37 Differences in the distribution of variables among subsets of patients were analyzed using Fisher’s exact test.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Morphology and immunohistochemistry.

The distribution of cases according to the histologic subtypes and the results of immunohistochemistry are shown in Table 1. All cases were positive for both CD30 and EMA, and ALK protein expression was found in 74 of 80 (93%) cases tested. Among the 6 cases proven to be ALK−, 3 were common ALCL and 3 lymphohistiocytic ALCL.

Histologic Subtype and Immunophenotype: Description of the Patients, Outcome, Prognostic Value of Histologic Typing, and Immunophenotyping

| Characteristics . | MD . | Patients . | Outcome . | Univariate Analysis P* . | Multivariate Analysis P† . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Patients . | % . | No. of Events . | 3-yr EFS . | ||||

| All | 82 | 25 | 66% [54-76%] | ||||

| Histologic subtype | 8 | .02‡ | .35‡ | ||||

| Common type | 48 | 65% | 12 | 73% [58-85%] | |||

| Lympho-histiocytic (LH) | 13 | 17% | 8 | 16% [3-53%] | |||

| Pure LH | 7 | 9% | |||||

| Common plus LH | 6 | 8% | |||||

| Other | 13 | 17% | 3 | 76% [48-91%] | |||

| Small-cell variant | 5 | 7% | |||||

| Common plus small cell | 6 | 8% | |||||

| Giant-cell variant | 1 | 1% | |||||

| Mixed (other) | 1 | 1% | |||||

| Immunophenotype | |||||||

| T/null/B phenotype | 12 | .11 | .27 | ||||

| T | 61 | 87% | 16 | 70% [56-81%] | |||

| Null | 9 | 13% | 5 | 44% [19-73%] | |||

| B | 0 | 0% | — | ||||

| CD30 | 0 | 82 | 100% | ||||

| EMA | 0 | 82 | 100% | ||||

| ALK-1 | 2 | 74 | 93% | 24 | 64% [52-75%] | .32 | — |

| BNH9 | 4 | 61 | 78% | 19 | 66% [52-77%] | .66 | — |

| Characteristics . | MD . | Patients . | Outcome . | Univariate Analysis P* . | Multivariate Analysis P† . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Patients . | % . | No. of Events . | 3-yr EFS . | ||||

| All | 82 | 25 | 66% [54-76%] | ||||

| Histologic subtype | 8 | .02‡ | .35‡ | ||||

| Common type | 48 | 65% | 12 | 73% [58-85%] | |||

| Lympho-histiocytic (LH) | 13 | 17% | 8 | 16% [3-53%] | |||

| Pure LH | 7 | 9% | |||||

| Common plus LH | 6 | 8% | |||||

| Other | 13 | 17% | 3 | 76% [48-91%] | |||

| Small-cell variant | 5 | 7% | |||||

| Common plus small cell | 6 | 8% | |||||

| Giant-cell variant | 1 | 1% | |||||

| Mixed (other) | 1 | 1% | |||||

| Immunophenotype | |||||||

| T/null/B phenotype | 12 | .11 | .27 | ||||

| T | 61 | 87% | 16 | 70% [56-81%] | |||

| Null | 9 | 13% | 5 | 44% [19-73%] | |||

| B | 0 | 0% | — | ||||

| CD30 | 0 | 82 | 100% | ||||

| EMA | 0 | 82 | 100% | ||||

| ALK-1 | 2 | 74 | 93% | 24 | 64% [52-75%] | .32 | — |

| BNH9 | 4 | 61 | 78% | 19 | 66% [52-77%] | .66 | — |

Under patients, the number of patients in the subsets is given. Under outcome, the number of events in the subsets is given. For the variables defining two subgroups, only the data concerning the group with the poorer outcome have been given. The number of events in the complementary group can be deducted by subtraction.

Abbreviation: MD, number of missing data for the variable.

P value of the two-tailed logrank test comparing each subset with the complementary group, adjusted on the chemotherapy protocol (univariate analysis).

P value in the multivariate analysis, adjusted on the chemotherapy regimen.

Because EFS of the common type overlaps with that of the so-called others, these two groups have been pooled, to conduct a comparison between lympho-histiocytic (pure or mixed) and non–lympho-histiocytic (P = .02). This binary variable has been tested in the Cox model.

Cytogenetic analysis.

The t(2;5) (p23;q35) translocation was demonstrated in 23 cases. An additional case showed a t(1;2) (q25;p23) translocation involving the same breakpoint on chromosome 2 as in the classic t(2;5) translocation. In 1 case, the karyotype showed complex chromosomal abnormalities with several structural rearrangements. The karyotype was normal in 5 cases, of which 4 were positive for the ALK1 antibody.

Clinical features.

The main clinical findings are given in Table 2. Ages ranged from 17 months to 17 years (median age, 10 years). The clinical presentation did not vary according to the immunophenotype or according to the histologic subtype, except for a borderline excess of B symptoms (P = .05) and visceral involvement (P = .06) in the patients with the lymphohistiocytic subtype.

Patient Characteristics and Outcome: Prognostic Value of the Clinical Variables

| Characteristics . | MD . | Patients . | Outcome . | Univariate Analysis P* . | Multivariate Analysis P† . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Patients . | % . | No. of Events . | 3-yr EFS . | ||||

| All | 82 | 25 | 66% [54-76%] | ||||

| Age ≥10 yr | — | 38 | 46% | 10 | 69% [51-82%] | .81 | — |

| Male | — | 46 | 56% | 12 | 68% [52-81%] | .36 | — |

| St Jude stage | .006 | .54 | |||||

| Stage I and II | 23 | 28% | 2 | 94% [41-68%] | |||

| Stage III and IV | — | 59 | 72% | 23 | 55% [74-99%] | ||

| Ann Arbor stage | .05 | .37 | |||||

| Stage I and II | 25 | 30% | 4 | 86% [66-95%] | |||

| Stage III and IV | — | 57 | 70% | 21 | 57% [42-70%] | ||

| B symptoms | — | 56 | 68% | 20 | 60% [46-73%] | .16 | .25 |

| Adenomegaly | — | 77 | 94% | NA | |||

| Peripheral | — | 72 | 88% | NA | |||

| Intra-abdominal | — | 32 | 39% | NA | |||

| Mediastinal | — | 32 | 39% | 17 | 39% [23-58%] | .0002 | .01 |

| Extra-nodal disease | — | 49 | 60% | NA | |||

| Any visceral involvement | — | 28 | 34% | 15 | 43% [26-62%] | .0004 | .05 |

| Splenomegaly | — | 17 | 21% | 9 | 40% [19-66%] | .02 | .51 |

| Hepatomegaly | — | 14 | 17% | 8 | 38% [16-66%] | .005 | .51 |

| Lung | — | 11 | 13% | 8 | 18% [4-56%] | .00008 | .09 |

| Pleural effusion | — | 6 | 7% | NA | |||

| Other viscera‡ | — | 3 | 4% | NA | |||

| Skin | — | 27 | 33% | 13 | 44% [25-65%] | .01 | .16 |

| Bone marrow | — | 13 | 16% | 6 | 43% [18-72%] | .10 | .67 |

| Bone | — | 10 | 12% | 2 | 78% [45-94%] | .45 | — |

| Soft tissue | — | 10 | 12% | 3 | 64% [32-87%] | .84 | — |

| CNS | — | 0 | 0% | ||||

| LDH ≥800 UI/L | 10 | 13 | 18% | 7 | 37% [16-65%] | .009 | .05 |

| Characteristics . | MD . | Patients . | Outcome . | Univariate Analysis P* . | Multivariate Analysis P† . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Patients . | % . | No. of Events . | 3-yr EFS . | ||||

| All | 82 | 25 | 66% [54-76%] | ||||

| Age ≥10 yr | — | 38 | 46% | 10 | 69% [51-82%] | .81 | — |

| Male | — | 46 | 56% | 12 | 68% [52-81%] | .36 | — |

| St Jude stage | .006 | .54 | |||||

| Stage I and II | 23 | 28% | 2 | 94% [41-68%] | |||

| Stage III and IV | — | 59 | 72% | 23 | 55% [74-99%] | ||

| Ann Arbor stage | .05 | .37 | |||||

| Stage I and II | 25 | 30% | 4 | 86% [66-95%] | |||

| Stage III and IV | — | 57 | 70% | 21 | 57% [42-70%] | ||

| B symptoms | — | 56 | 68% | 20 | 60% [46-73%] | .16 | .25 |

| Adenomegaly | — | 77 | 94% | NA | |||

| Peripheral | — | 72 | 88% | NA | |||

| Intra-abdominal | — | 32 | 39% | NA | |||

| Mediastinal | — | 32 | 39% | 17 | 39% [23-58%] | .0002 | .01 |

| Extra-nodal disease | — | 49 | 60% | NA | |||

| Any visceral involvement | — | 28 | 34% | 15 | 43% [26-62%] | .0004 | .05 |

| Splenomegaly | — | 17 | 21% | 9 | 40% [19-66%] | .02 | .51 |

| Hepatomegaly | — | 14 | 17% | 8 | 38% [16-66%] | .005 | .51 |

| Lung | — | 11 | 13% | 8 | 18% [4-56%] | .00008 | .09 |

| Pleural effusion | — | 6 | 7% | NA | |||

| Other viscera‡ | — | 3 | 4% | NA | |||

| Skin | — | 27 | 33% | 13 | 44% [25-65%] | .01 | .16 |

| Bone marrow | — | 13 | 16% | 6 | 43% [18-72%] | .10 | .67 |

| Bone | — | 10 | 12% | 2 | 78% [45-94%] | .45 | — |

| Soft tissue | — | 10 | 12% | 3 | 64% [32-87%] | .84 | — |

| CNS | — | 0 | 0% | ||||

| LDH ≥800 UI/L | 10 | 13 | 18% | 7 | 37% [16-65%] | .009 | .05 |

Under patients, the number of patients in the subsets is given. Under outcome, the number of events in the subsets is given. For the variables defining two subgroups, only the data concerning the group with the poorer outcome have been given. The number of events in the complementary group can be deducted by subtraction.

Abbreviations: MD, number of missing data for the variable; NA, not assessed.

P value of the two-tailed logrank test comparing each subset with the complementary group, adjusted on the chemotherapy protocol (univariate analysis).

P value in the multivariate analysis, adjusted on the chemotherapy regimen. The underlined results are those of the variables selected in the final Cox model (P to remove from the model); the other ones are those of the variables rejected from the model (P to enter in the model).

Other viscera are pancreas, kidney, and pericardium.

Results of Treatment

Remission.

Seventy-eight patients (95%) achieved a CR, 68 (87%) of which achieved the CR within 3 months of the beginning of the treatment. Eight patients underwent surgery for a residual mass, which was completely necrotic in 7 cases. The last patient, who had viable cells in the resected residual tumor after the third course of chemotherapy, achieved a CR after further therapy and is alive with no evidence of disease and 60 months of follow-up. Four patients failed to achieve a CR. Three of them died 5 to 12 months after the diagnosis and the last one is still on therapy.

Relapses.

Twenty-one patients relapsed 7 to 49 months after diagnosis (median, 10 months). All but 2 relapses occurred within 2 years of the diagnosis. In 20 of 21 patients, the site of the relapse was the nodes, which were associated or not associated with other sites of disease. There were no first recurrences in the CNS. The site of relapse was restricted to the initial site of the disease in only 3 patients. Treatment for relapses was rather heterogeneous: 15 patients received carmustine, vinblastine, cytarabine, associated or not associated with bleomycin, and various treatments were administered to the others. A second remission was obtained in 17 of 21. Overall, 8 patients died 1 to 24 months from the first relapse and 13 patients are alive in second (7 patients), third (4 patients), or fourth remission (2 patients), with a median follow-up of 48 months (range, 5 to 93 months) since the first relapse.

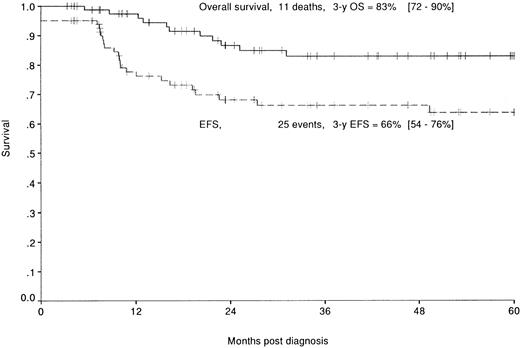

Survival.

Median follow-up of this population is 49 months (range, 3 to 105 months). Eleven patients died of their disease 5 to 31 months after diagnosis. Overall and EFS rates are, respectively, 83% (72% to 90%) and 66% (54% to 76%) at 3 years (Fig 2).

Overall (—) and EFS (–––) of the 82 patients enrolled in the HM89 and HM91 studies.

Overall (—) and EFS (–––) of the 82 patients enrolled in the HM89 and HM91 studies.

Prognostic factors.

The results of the univariate analysis are shown in Tables 1 and 2. In the Cox regression analysis, three parameters were found to be predictive of a higher risk of failure: a mediastinal mass (RR = 3.1 [1.2 B 8.0]), any visceral involvement (RR = 2.5 [1.0 to 6.5]), and LDH ≥800 UI/L (RR = 2.7 [1.0 to 6.8]).

The combination of these three parameters in the 75 patients for whom data were available allowed us to define two groups (P = .0001): a low-risk group with none of these failure risk factors (29 patients, 2 events) with a 3-year EFS of 95% (75% to 99%) and a high-risk group with at least one of these poor prognostic factors (46 patients, 22 events) with a 3-year EFS of 47% (325 to 62%). The EFS curves according to this classification are shown in Fig 3.

EFS according to the risk group: low-risk group (no mediastinal or visceral involvement, LDH <800 UI/L [—]) and high-risk group (mediastinal and/or visceral involvement and/or LDH ≥800 UI/L [···]) of the patients enrolled in the HM 89 and HM 91 studies.

EFS according to the risk group: low-risk group (no mediastinal or visceral involvement, LDH <800 UI/L [—]) and high-risk group (mediastinal and/or visceral involvement and/or LDH ≥800 UI/L [···]) of the patients enrolled in the HM 89 and HM 91 studies.

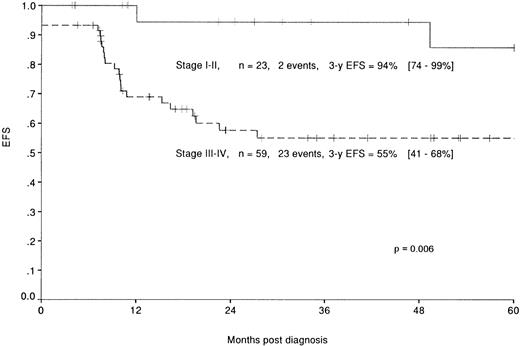

As shown in Table 3 and on Fig 4, St Jude’s system also led to a discriminating classification: patients with a stage I or II disease (23 patients, 2 events) have a 3-year EFS rate of 94% (74% to 99%), whereas stage III or IV disease (59 patients, 23 events) have a 3-year EFS rate of 55% (41% to 68%). However, the prognostic value of this classification system proved less significant (P = .006) than the classification defined above. The outcome of the patients according to their classification in these 2 systems is shown in Table3.

Comparison of the Classification According to the St Jude’s Staging System With the Classification According to the Prognostic Factors Defined in This Study

| New Classification . | St Jude’s Classification . | |

|---|---|---|

| Stage I or II . | Stage III or IV . | |

| Neither mediastinum, neither visceral involvement, nor elevated LDH | N = 17 E = 1 3-yr EFS = 100% | N = 12 E = 1 3-yr EFS = 86% [49-97%] |

| At least one of these risk factors | N = 4 E = 1 3-yr EFS = 67% [21-94%] | N = 42 E = 21 3-yr EFS = 45% [30-61%] |

| New Classification . | St Jude’s Classification . | |

|---|---|---|

| Stage I or II . | Stage III or IV . | |

| Neither mediastinum, neither visceral involvement, nor elevated LDH | N = 17 E = 1 3-yr EFS = 100% | N = 12 E = 1 3-yr EFS = 86% [49-97%] |

| At least one of these risk factors | N = 4 E = 1 3-yr EFS = 67% [21-94%] | N = 42 E = 21 3-yr EFS = 45% [30-61%] |

Abbreviations: N, number of patients in each group; E, number of events in each group.

EFS of the patients enrolled in the HM protocols according to the stage in the St Jude’s classification: stage I and II (—) and stage III and IV (–––).

EFS of the patients enrolled in the HM protocols according to the stage in the St Jude’s classification: stage I and II (—) and stage III and IV (–––).

Outcome of the patients excluded from analysis.

With a median follow-up of 44 months, no difference was noted in the 3-year overall survival (86% [77% to 92%]) and EFS (69% [59% to 78%]) survival rates between the whole population of 112 patients (including the patients excluded from analysis) and the study patients.

DISCUSSION

ALCL is now a widely recognized clinico-pathologic entity included in the recent REAL of lymphoid neoplasms.5 However, several areas of disagreement and controversies remain. One reason for these disagreements may lie in the different criteria used for its diagnosis. The criteria we considered mandatory for the diagnosis of ALCL, ie, characteristic cells of the T or the null phenotype and coexpression of CD30 and EMA antigens,26 are rather strict, which probably explains the high percentage of cases (15%) in which the initial diagnoses of ALCL was not confirmed after re-examination of slides by the panel of pathologists. One of the most difficult diagnoses is the putative but controversial Hodgkin’s-like ALCL. Seven cases initially diagnosed as Hodgkin’s-like ALCL were subsequently diagnosed as Hodgkin’s disease after re-examination with immunohistochemistry. All of these cases showed malignant cells with a typical phenotype (CD30+, CD15+, EMA−) and were all ALK−. Another area of disagreement concerns whether ALCL of the B phenotype exists or not. Proliferations of the B phenotype were in fact excluded from our series. Three cases in the present series, all ALK−, were initially diagnosed as ALCL and were reclassified as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

On the other hand, the strikingly higher percentage of the cases positive for ALK1 (92% [74/80]) and probably associated with the t(2;5) translocation in the present series compared with that previously reported26 could be due to the strictness of diagnostic criteria. These results also suggest that the t(2;5) translocation is probably more frequent in childhood ALCL than in adults, in whom it has been reported in less than 40% of the cases investigated by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)38,39 or ALK1 immunostaining.27 ALK-1 expression was demonstrated to have no prognostic value in the present study, which is not surprising given the small number (n = 6) of negative cases. Nevertheless, the ALK1 antibody has provided pathologists with a major tool for the diagnosis of ALCL.

Several series of childhood and adult ALCL have been reported so far, but it is often difficult to compare them because of the small number of patients in each study and the lack of a common staging system.19-21,40-43 Comparisons with series from North America also pose a problem, because all the large-cell lymphomas are treated with the same protocols regardless of the histologic subgroup and treatments are stratified according to the St Jude’s classification.22 In these series, neither ALCL histology nor CD30 expression44 nor ALK-1 positivity45was shown to be significantly associated with survival, whereas the B-cell phenotype was associated with a better outcome.46

In the present study, treatment was not stratified according to initial disease extension. The multivariate analysis showed three factors associated with an increased risk of failure: mediastinal involvement, visceral involvement, and an LDH level exceeding 800 UI/L. Based on these results, two groups could be defined for treatment according to risks: a low-risk group free of mediastinal and visceral involvement and with LDH <800 UI/L and a high-risk group with at least one risk factor.

With the St Jude’s staging system,32 usually used for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, the outcome of patients with stage I and II disease is excellent. However, patients classified as stage III or IV according to the St Jude’s classification but with none of the risk factors defined in our study seem to have a good outcome. Our prognostic factors classification is therefore probably more discriminating for ALCL than the St Jude’s classification, because the low-risk group has an EFS that almost exactly overlaps that of stage I/II patients, according to St Jude’s system, but comprises more patients (mostly subjects with St Jude’s stage III disease without mediastinal involvement), whereas the outcome is poorer for the high-risk group comprising less patients than the St Jude’s stage III/IV. Besides, the St Jude’s staging system is sometimes difficult to use to classify patients with ALCL, especially for those with skin lesions.

The prognostic significance of skin lesions was not demonstrated in the multivariate analysis when adjusted on mediastinal and visceral involvement, probably because they are linked to the presence of visceral lesions. This was contrary to expectations, because an independent poor prognostic value had previously been found for skin lesions in the first patients in this series47 and has been reported in other pediatric series.19 This underlines how difficult it is to draw firm conclusions based on multivariate analysis of such small series of patients.

The optimal therapy for patients with ALCL has yet to be determined. In most pediatric or adult studies, high CR rates have been achieved with induction treatment. However, as in our series, recurrence rates are quite high in the majority of the previous reports, with EFS rates ranging from 39% to 81%. These relapses usually occur within a few months after the end of the treatment. Such early relapses raise questions about the usefulness of maintenance treatment. Indeed, in the study reported by Vecchi et al20 of patients treated for 2 years with chemotherapy, the EFS rate was not different from that of series in which patients received a shorter treatment and the relapses were delayed after the end of the treatment. In contrast, the good results achieved with the BFM therapy19 completed within 2 to 5 months and that yielded an EFS rate of 81% in 62 patients are in favor of short intensive treatment. This strategy, which is usually efficient in B-cell lymphoma, may also be adequate for ALCL, although the majority of them have a T-cell immunophenotype. The relationship between ALCL and Hodgkin’s disease raises the question as to whether radiotherapy would be useful for involved sites, as proposed in Hodgkin’s disease. However, it would probably be of limited benefit, because the majority of the relapses occur in sites that are not involved at diagnosis.

No CNS relapses occurred as the first event, although CNS prophylaxis only consisted in high-dose methotrexate (3 g/m2) without intrathecal therapy or any CNS irradiation. These results are comparable to those of previous reports that indicate that there are no19 or only very rare20,21 CNS relapses, even in series of children21 or adults40 43 who received no intrathecal therapy and no (or only very few) courses of high-dose methotrexate. This finding raises the question as to whether CNS prophylaxis is necessary in this disease.

Given the excellent results of the BFM strategy for childhood ALCL,19 in which the duration of the treatment and the cumulative doses of chemotherapy especially alkylating agents and anthracyclines are much lower than in the HM protocols, the treatment of the low-risk group may certainly be reduced in duration and intensity. On the contrary, the high-risk group, whose 3-year EFS rate is only 47%, should benefit from novel therapeutic approaches. Given the rarity of this disease, the efficacy of such strategies could only be assessed through large international prospective studies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors are grateful to Lorna Saint Ange for editing the manuscript.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to L. Brugières, MD, Department of Pediatrics, Institut Gustave Roussy, 39, rue CamilleDesmoulins, 94805 Villejuif, France.

![Fig. 3. EFS according to the risk group: low-risk group (no mediastinal or visceral involvement, LDH <800 UI/L [—]) and high-risk group (mediastinal and/or visceral involvement and/or LDH ≥800 UI/L [···]) of the patients enrolled in the HM 89 and HM 91 studies.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/92/10/10.1182_blood.v92.10.3591/4/m_blod42230003x.jpeg?Expires=1769141274&Signature=nHfpEimMi~HmlLDuYqy4mCTvUpakCrXG~8nHR0w8fNEWTYhySeWlZUo7MkRPwVo3MG0VgsHTrJS9X8XuuMmTCEOU0cEV4Qo5frV9LhWliVk4kqhKQEJZOSq~Ih2k3wx4tUzcZJq2UWPx9pVuq9bIVwtK5IGU0WkgypVB~oiNDdyI-L-49gp6ri3nkOI4IocwWZX1RTzL29YvKx3A8BcDEaarw3-vsiD4VyUojyT~3-u~1tRkK1bOvxzKdEyyKWNzB7oi~0AFbt4K2VhZc0ug8BHtrziDe~j5i5RkKD5-sN6YadP2OAZIOxOqOmMBAZO0TySFXlkd19WhD8Bses9I5g__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)