Abstract

Thrombocytopenia has been characterized in six patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) with respect to the delivery of viable platelets into the peripheral circulation (peripheral platelet mass turnover), marrow megakaryocyte mass (product of megakaryocyte number and volume), megakaryocyte progenitor cells, circulating levels of endogenous thrombopoietin (TPO) and platelet TPO receptor number, and serum antiplatelet glycoprotein (GP) IIIa49-66 antibody (GPIIIa49-66Ab), an antibody associated with thrombocytopenia in HIV-infected patients. Peripheral platelet counts in these patients averaged 46 ± 43 × 103/μL (P = .0001 compared to normal controls of 250 ± 40× 103/μL), and the mean platelet volume (MPV) was 10.5 ± 2.0 fL (P > 0.3 compared with normal control of 9.5 ± 1.7 fL). The mean life span of autologous111In-platelets was 87 ± 39 hours (P = .0001 compared with 232 ± 38 hours in 20 normal controls), and immediate mean recovery of 111In-platelets injected into the systemic circulation was 33% ± 16% (P = .0001 compared with 65% ± 5% in 20 normal controls). The resultant mean peripheral platelet mass turnover was 3.8 ± 1.5 × 105 fL/μL/d versus 3.8 ± 0.4 × 105 fL/μL/d in 20 normal controls (P > .5). The mean endogenous TPO level was 596 ± 471 pg/mL (P = .0001 compared with 95 ± 6 pg/mL in 98 normal control subjects), and mean platelet TPO receptor number was 461 ± 259 receptors/platelet (P = .05 compared with 207 ± 99 receptors/platelet in nine normal controls). Antiplatelet GPIIIa49-66Ab levels in sera were uniformly increased in HIV thrombocytopenic patients (P < .001). In this cohort of thrombocytopenic HIV patients, marrow megakaryocyte number was increased to 30 ± 15 × 106/kg (P = .02 compared with 11 ± 2.1 × 106/kg in 20 normal controls), and marrow megakaryocyte volume was 32 ± 0.9 × 103 fL (P = .05 compared with 28 ± 4.5 × 103 fL in normal controls). Marrow megakaryocyte mass was expanded to 93 ± 47 × 1010 fL/kg (P = .007 compared with normal control of 31 ± 5.3 × 1010 fL/kg). Marrow megakaryocyte progenitor cells averaged 3.3 (range, 0.4 to 7.3) CFU-Meg/1,000 CD34+ cells compared with 27 (range, 0.1 to 84) CFU-Meg/1,000 CD34+ cells in seven normal subjects (P = .02). Thus, thrombocytopenia in these HIV patients was caused by a combination of shortening of platelet life span by two thirds and doubling of splenic platelet sequestration, coupled with ineffective delivery of viable platelets to the peripheral blood, despite a threefold TPO-driven expansion in marrow megakaryocyte mass. We postulate that this disparity between circulating platelet product and marrow platelet substrate results from direct impairment in platelet formation by HIV-infected marrow megakaryocytes.

CHRONIC THROMBOCYTOPENIA develops in approximately one third of individuals infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) during the course of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).1-3 The pathophysiologic bases for the development of thrombocytopenia in HIV-infected patients has been ascribed to changing proportions of three variables: immune-mediated platelet destruction, enhanced platelet splenic sequestration, and impaired platelet production.1,2,4-8Kinetic studies demonstrate shortened platelet life span in thrombocytopenic HIV-infected patients, suggesting that platelet production was not sufficiently expanded to compensate for accelerated platelet destruction in these patients.5,9 This study was designed to characterize platelet production in a cohort of HIV-infected patients with chronic thrombocytopenia by measuring the relative contributions of impaired platelet production, increased platelet removal, augmented splenic sequestration, marrow megakaryocytopoietic responsiveness to stimulation by endogenous thrombopoietin, and antiplatelet GPIIIa49-66Ab, an antibody directed against the newly described immunodominant epitope in HIV-infected patients with thrombocytopenia.10

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients studied.

Thrombocytopenic HIV-infected patients were recruited from the Ponce de Leon Center, a free-standing infectious disease clinic affiliated with Grady Memorial Hospital in Atlanta, GA. Six men with HIV-associated thrombocytopenia of longer than 6 months duration were studied. Their hematologic, viral, and overall clinical evaluation are presented in Table 1. None of the patients was on any medication known to affect platelet counts or function, nor had they changed antiviral therapy within 3 months before entering the study. Informed consent was obtained from each participant upon admission to the Generalized Clinical Research Center (GCRC) at Emory University (Atlanta, GA). A detailed clinical history, physical examination, complete blood counts, serum chemistries, urinalysis, chest radiograph, and electrocardiogram were obtained at that time.

Clinical Course and Hematologic Status of HIV Thrombocytopenic Patients

| . | Normal Values . | #1 . | #2 . | #3 . | #4 . | #5 . | #6 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical course | 39-yr-old man infected with HIV for 12 yr and thrombocytopenic for 3 yr without splenomegaly | 41-yr-old man infected with HIV for 4 yr and thrombocytopenic for 4 yr | 32-yr-old man infected with HIV for 12 yr and thrombocytopenic for 4 yr | 42-yr-old man infected with HIV for 12 yr and thrombocytopenic for 3 yr | 40-yr-old man infected with HIV for 4 yr and thrombocytopenic for 4 yr | 22-yr-old man infected with HIV for _ yr and thrombocytopenic for 4 yr | |

| Platelet count (cells × 103/μL) | 250 ± 60 | 102 | 5 | 25 | 8 | 98 | 39 |

| Erythrocyte count (cells × 106/μL) | 5.2 ± 0.3 | 4.15 | 4.98 | 4.96 | 5.1 | 4.7 | 3.88 |

| Leukocyte count (cells × 103/μL) | 7.4 ± 2.0 | 1.0 | 6.1 | 1.6 | 11.3 | 1.9 | 4.9 |

| CD4+ T cells (cells/μL) | >750 | 10 | 639 | 137 | 189 | 88 | 3 |

| Viral load (copies × 103/μL) | Not detected | 0.16 | 8.3 | 32 | 366 | 44 | 9 |

| . | Normal Values . | #1 . | #2 . | #3 . | #4 . | #5 . | #6 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical course | 39-yr-old man infected with HIV for 12 yr and thrombocytopenic for 3 yr without splenomegaly | 41-yr-old man infected with HIV for 4 yr and thrombocytopenic for 4 yr | 32-yr-old man infected with HIV for 12 yr and thrombocytopenic for 4 yr | 42-yr-old man infected with HIV for 12 yr and thrombocytopenic for 3 yr | 40-yr-old man infected with HIV for 4 yr and thrombocytopenic for 4 yr | 22-yr-old man infected with HIV for _ yr and thrombocytopenic for 4 yr | |

| Platelet count (cells × 103/μL) | 250 ± 60 | 102 | 5 | 25 | 8 | 98 | 39 |

| Erythrocyte count (cells × 106/μL) | 5.2 ± 0.3 | 4.15 | 4.98 | 4.96 | 5.1 | 4.7 | 3.88 |

| Leukocyte count (cells × 103/μL) | 7.4 ± 2.0 | 1.0 | 6.1 | 1.6 | 11.3 | 1.9 | 4.9 |

| CD4+ T cells (cells/μL) | >750 | 10 | 639 | 137 | 189 | 88 | 3 |

| Viral load (copies × 103/μL) | Not detected | 0.16 | 8.3 | 32 | 366 | 44 | 9 |

Study design.

The study was designed to characterize platelet production in these patients by determining (1) autologous 111In-platelet mass turnover, a measure of platelet delivery into the peripheral circulation and defined in the steady state as effective platelet production; (2) marrow megakaryocyte mass, the product of megakaryocyte numbers and megakaryocyte volumes, represents the substrate from which platelets are formed, and defined as total platelet production; (3) marrow megakaryocyte progenitor cells obtained by stimulating CD34+ marrow mononuclear cells with pegylated recombinant human megakaryocyte growth and development factor (PEG-rHuMGDF); (4) serum levels of endogenous TPO, representing the thrombocytopoetic stimulus, and platelet TPO receptor numbers, a measure of TPO receptor density on precursor marrow megakaryocytes; and (5) serum antiplatelet GPIIIa49-66Ab, a marker of immune platelet injury. These results were related to measurements of plasma viral load, peripheral blood CD4+ T-cell counts, platelet, and marrow morphology.

Laboratory procedures.

Peripheral platelet counts, mean platelet volumes (MPV), red blood cell (RBC) counts, and total white blood cell (WBC) counts were determined in whole blood collected in Na2EDTA (2 mg/mL), using Serono/Baker model 9000 whole blood analyzer (Allentown, PA).11-13

The HIV serologic status of these patients was determined using a commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and confirmed with Western blot assay.14 Plasma HIV loads were determined by means of a reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR).15,16 The quantitative HIV RNA PCR assay was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Amplicor HIV-1 Monitor Test, Roche Diagnostic Systems, Branchburg, NJ). RNA was extracted from heparinized samples using silica.17 A total of 50 μL of each prepared RNA sample was used for the PCR assay. After amplification and detection of the PCR product, the initial HIV RNA load in each sample was calculated by comparing it with the internal quantitation standard; the results were expressed as HIV RNA copies per milliliter plasma.

Serum and platelet HIV-associated antibodies.

Antiplatelet GPIIIa49-66Ab profile was performed as recently described.10 In prior studies, the strong correlation between antiplatelet GPIIIa49-66Ab levels and thrombocytopenia, have been interpreted to reflect direct binding of these antiplatelet IgG antibodies directed against the immunodominant epitope GPIIIa49-66,10 as well as contributing to the binding of immune complexes to platelets.6

TPO levels in serum and TPO receptors on platelets.

Serum levels of endogenous TPO were determined using an ELISA involving an initial polyclonal antibody capture procedure followed by horseradish peroxidase (HPO)-linked signal antibody to generate color using TMB substrate.18-20 The assay was sensitive to 30 pg/mL and reproducible with 15% coefficient of variation.

Mean platelet TPO receptor numbers were estimated from platelet binding isotherms of 125I-labeled recombinant human (rHu) TPO according to Scatchard analysis.21 22 In brief, TPO receptors on platelets were determined using purified rHu-TPO, a gift from Amgen (Thousand Oaks, CA), radiolabeled by Iodo-beads iodination reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL). rHu-TPO was incubated with 50 mmol/L sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.2, and 125I with Iodo-beads for 15 minutes. Platelets were obtained from blood drawn in acid-citrate-dextrose (ACD) anticoagulant (1:7 vol/vol), pelleting platelets from platelet-rich plasma by centrifuging at 500g for 15 minutes, resuspension in Tyrode's buffer containing ACD (1:7 vol/vol), pH 6.2, 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA), and 0.01% Tween. Binding isotherms were obtained by incubating platelets in plasma-free Tyrode's buffer, ACD (1:7 vol/vol), 1% BSA, 0.01% Tween, pH 6.2, and various amounts of 125I-rHuTPO (40 to 640 ng/mL final concentrations) for 1 hour at room temperature. Nonspecific binding was assessed by comparing the effects of adding 100-fold excess unlabeled rHu-TPO 30 minutes before 125I-rHuTPO was added. Nonspecific binding ranged from 10% to 20%. Binding isotherms were analyzed using the Biosoft Ligand Program (Cambridge, UK) to determine the number of binding classes, the number of molecules bound/platelet, and the dissociation constant.

Platelet kinetic measurements.

To measure platelet life span, autologous platelets were labeled with111In-oxine, using the method described previously.23 Labeling efficiencies averaged 90%, and the labeled platelets functioned normally.24,25 After reinjection, twice-daily blood samples were collected and analyzed for111In-platelet activity to determine the rate at which111In-platelets were cleared from the circulation. Platelet life span (ie, the average time platelets remained in circulation) was then calculated using computer least-squares fitting of the raw data to a γ-function modeling program.23 The immediate recovery of injected 111In-platelets in the circulation was estimated by extrapolating the platelet radioactivity disappearance curve to time zero and estimating the blood volume (70 mL/kg), using the formula:

The results were compared with two groups of thrombocytopenic patients: (1) 17 patients with megakaryocyte hypoplasia; and (2) 9 patients with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Data regarding these two groups have been reported previously.23

Steady-state platelet mass turnover was calculated by multiplying the peripheral platelet concentration by the mean platelet volume and dividing by platelet life span and the percentage recovery of injected radiolabeled autologous platelets. In the steady state, platelet mass turnover was a measure of the rate at which viable platelet mass was delivered to the peripheral blood.26

Marrow megakaryocytopoiesis.

Megakaryocyte number, size, and ploidy were measured by flow cytometry, using a previously reported method for multiparameter correlative marrow analysis with a single-argon-ion-laser fluoroscein-activated cell sorter (FACS) analyzer (FACScan Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA).27-31 Cell DNA in aspirated marrow was stained with propidium iodide, and surface membrane receptors were analyzed with antibodies labeled with fluorescein. Megakaryocytes expressing platelet GPIIb/IIIa were enumerated in relation to the nucleated erythroid precursors expressing glycophorin A.30,32 Measurements of megakaryocyte diameters were based on the time-of-flight principle, the time required for a cell in suspension to pass through a focused light beam.27,28,30 31 Aspirated bone marrow (3 mL) obtained from the pelvic bones was collected into 10-mL plastic syringes containing equal volumes of ACD (formula A), 2.5 mmol/L EDTA and 2.2 μmol/L prostaglandin E1 (PGE1) (Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, MO), final concentrations. The marrow was gently pipetted, passed through a 120-μm monofilament nylon filter, and diluted with cold Ca2+-free and Mg2+-free phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 13.6 mmol/L sodium citrate, 2.2 μmol/L PGE1, 1 mmol/L theophylline (Sigma), 3% BSA (Fraction V; Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA), 11 mmol/L glucose, and adjusted to a pH of 7.3 and an osmolarity of 290 mOsm/L. Megakaryocytes were analyzed in marrow aspirates fractionated with 1.06 density Percoll (Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ). The nucleated erythroid marrow cells were analyzed from marrow separated over 1.08 density Percoll (Pharmacia Biotech). Megakaryocytes were selected on the basis of their distinct immunofluorescence at levels above that of control cells labeled with an unrelated monoclonal antibody (MoAb). In each sample, at least 2,000 to 3,000 megakaryocytes were analyzed. Flow cytometric analysis was performed using FACScan Lysis Program (Becton Dickinson).

Marrow CD34+ megakaryocyte progenitors.

The assays for colony-forming unit-megakaryocyte (CFU-Meg) was based on a plasma clot matrix formed from human citrated AB plasma.34 Aliquots of 5 to 10 mL bone marrow were collected in heparin. Cells were diluted in modified Hanks' buffered saline solution (HBSS) layered over Ficoll-Hypaque and centrifuged at 2,000 rpm in a Sorvall RT6000 at room temperature for 30 minutes. The mononuclear layer was collected, diluted with HBSS, washed twice by centrifugation at 1,500 rpm, for 5 min/wash, and then counted. CD34+ cells used in the megakaryocyte assay were selected using the Miltenyi Biotech MiniMACS magnetic cell separation kit (Miltenyi Biotech, Sunnyvale, CA). Postcolumn purity of the CD34+ cell fraction was determined by staining an aliquot of cells with phycoerythrin-conjugated HPCA-2 MoAb (BDIS, San Jose, CA) and subsequent FACS analysis. PEG-rHuMGDF was used at a final concentration of 10 ng/mL and cells were plated in a modified IMDM medium at 2 × 104 cells/mL in 15% human AB plasma. Cells were cultured in a 24-well microtiter plate with 300-μL/well volumes in triplicate for 8 days in a 37°C incubator with 5% CO2humidity. Cultures were fixed with methanol/acetone (1:2) and stained with CD41/42 (GPIIb/IIIa) antiplatelet antibodies, followed by goat anti-mouse FITC. Nuclei were stained with propidium iodide. A CFU-Meg colony was defined as 3 or more brightly fluorescent cells by inverted fluorescence microscopy.

Morphology.

Marrow aspirates and cores were obtained from the posterior superior iliac crest. Core biopsy specimens were fixed in 10% buffered formalin solution, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned. Aspirate and core samples were stained with polychromatophilic dyes for examination at the light level.

Data analysis.

Data were analyzed using SIGMA STAT (Jandel Scientific Software, San Rafael, CA). Comparisons between two groups were performed using the two-tailed Student's t-test, unless the data were not distributed randomly, in which case nonparametric analysis was performed. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare values for a particular group at various time points.35 Unless otherwise stated, variance about the mean is given as ±1 SD.

RESULTS

The hematologic, viral, and overall clinical characteristics of this cohort of thrombocytopenic HIV-infected patients are presented in Table1. HIV viral loads ranged from 0.16 to 366 × 103 RNA viral copies/mL of plasma. In five of the six patients, the CD4+ T-cell counts were less than 250 cells/μL. The peripheral erythrocyte counts were within the range for normals (P > .1), but only two of the six patients had normal leukocyte counts (Table 1).

The peripheral platelet concentrations in these six thrombocytopenic HIV-infected patients averaged 46 ± 43 (range, 5 to 102) × 103/μL (P = .0001 compared with 250 ± 40 × 103/μL in 98 normal controls; Table2). The MPV was 10.5 ± 2.0 fL, not significantly different from the normal controls of 9.5 ± 1.7 fL (Table 2; P > .3).

Platelet Production and Kinetics in HIV-Infected Patients With Thrombocytopenia

| . | Normal Controls (no.) . | HIV Patients (6) . | #1 . | #2 . | #3 . | #4 . | #5 . | #6 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Platelet Formation | ||||||||

| Platelet count (×103/μL) | 250 ± 40 (98) | 46 ± 43 | 102 | 5 | 25 | 8 | 98 | 39 |

| P < 10−4 | ||||||||

| MPV (fL) | 9.5 ± 1.7 (98) | 10.5 ± 2.0 | 8.7 | 13.7 | 11.2 | 10.7 | 8 | 10.9 |

| P > 0.3 | ||||||||

| Antiplatelet gpIIIa49-66 antibodies (arbitrary OD units) | ≤21 (20) | 129 ± 91 P < .001 | 266 | 188 | 60 | 169 | 27 | 65 |

| Recovery (%) | 65 ± 5 (20) | 33 ± 16 | 64 | 23 | 23 | 24 | 29 | 35.5 |

| P < 10−4 | ||||||||

| Platelet life span (h) | 232 ± 38 (20) | 87 ± 39 | 115 | 69 | 101 | 16.5 | 108 | 115 |

| P < 10−4 | ||||||||

| Platelet mass turnover (×105 fL/μL/d) | 3.8 ± 0.4 (20) | 3.8 ± 1.5 | 2.9 | 3.1 | 2.9 | 5.3 | 6 | 2.5 |

| P > 0.5 | ||||||||

| Thrombopoietic stimulus | ||||||||

| Serum endogenous TPO (pg/mL) | 95 ± 6 (98) | 596 ± 471 | 535 | 330 | 170 | 390 | 212 | 1900 |

| P < 10−3 | ||||||||

| Platelet TPO receptors (per platelet) | 207 ± 99 (9) | 461 ± 259 | 645 | 594 | 809 | 333 | 183 | 200 |

| P = .04 | ||||||||

| Megakaryocytopoiesis | ||||||||

| Megakaryocyte number (×106/kg) | 11 ± 2.1 (20) | 30 ± 15 | 14.6 | 31.8 | 8.5 | 48.8 | 36 | 37.6 |

| P = .02 | ||||||||

| Megakaryocyte vol (×103 fL) | 28 ± 4.5 (20) | 32 ± 0.9 | 32.2 | 30.3 | 32.5 | 31.5 | 31.9 | 31.9 |

| P = .05 | ||||||||

| Megakaryocyte Progenitors (megas/1,000 CD34+ cells) | 27 (9) | 3.3 P = .02 | 1.1 | 2.7 | 5.1 | 3.8 | 0.4 | 7.3 |

| Megakaryocyte mass (×1010 fL/kg) | 31 ± 5.3 (20) | 93 ± 47 | 47 | 96.4 | 27.6 | 154 | 115 | 119 |

| P = .007 |

| . | Normal Controls (no.) . | HIV Patients (6) . | #1 . | #2 . | #3 . | #4 . | #5 . | #6 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Platelet Formation | ||||||||

| Platelet count (×103/μL) | 250 ± 40 (98) | 46 ± 43 | 102 | 5 | 25 | 8 | 98 | 39 |

| P < 10−4 | ||||||||

| MPV (fL) | 9.5 ± 1.7 (98) | 10.5 ± 2.0 | 8.7 | 13.7 | 11.2 | 10.7 | 8 | 10.9 |

| P > 0.3 | ||||||||

| Antiplatelet gpIIIa49-66 antibodies (arbitrary OD units) | ≤21 (20) | 129 ± 91 P < .001 | 266 | 188 | 60 | 169 | 27 | 65 |

| Recovery (%) | 65 ± 5 (20) | 33 ± 16 | 64 | 23 | 23 | 24 | 29 | 35.5 |

| P < 10−4 | ||||||||

| Platelet life span (h) | 232 ± 38 (20) | 87 ± 39 | 115 | 69 | 101 | 16.5 | 108 | 115 |

| P < 10−4 | ||||||||

| Platelet mass turnover (×105 fL/μL/d) | 3.8 ± 0.4 (20) | 3.8 ± 1.5 | 2.9 | 3.1 | 2.9 | 5.3 | 6 | 2.5 |

| P > 0.5 | ||||||||

| Thrombopoietic stimulus | ||||||||

| Serum endogenous TPO (pg/mL) | 95 ± 6 (98) | 596 ± 471 | 535 | 330 | 170 | 390 | 212 | 1900 |

| P < 10−3 | ||||||||

| Platelet TPO receptors (per platelet) | 207 ± 99 (9) | 461 ± 259 | 645 | 594 | 809 | 333 | 183 | 200 |

| P = .04 | ||||||||

| Megakaryocytopoiesis | ||||||||

| Megakaryocyte number (×106/kg) | 11 ± 2.1 (20) | 30 ± 15 | 14.6 | 31.8 | 8.5 | 48.8 | 36 | 37.6 |

| P = .02 | ||||||||

| Megakaryocyte vol (×103 fL) | 28 ± 4.5 (20) | 32 ± 0.9 | 32.2 | 30.3 | 32.5 | 31.5 | 31.9 | 31.9 |

| P = .05 | ||||||||

| Megakaryocyte Progenitors (megas/1,000 CD34+ cells) | 27 (9) | 3.3 P = .02 | 1.1 | 2.7 | 5.1 | 3.8 | 0.4 | 7.3 |

| Megakaryocyte mass (×1010 fL/kg) | 31 ± 5.3 (20) | 93 ± 47 | 47 | 96.4 | 27.6 | 154 | 115 | 119 |

| P = .007 |

TPO serum levels and TPO platelet receptors.

Endogenous TPO levels in serum were increased by more than sixfold; ie, mean serum concentration of TPO was 596 ± 471 pg/mL compared with 95 ± 6 pg/mL in 98 normal subjects (Table 2;P = .0001).20 Binding studies using125I-labeled rHu-TPO demonstrated increased platelet TPO receptors in thrombocytopenic HIV-infected patients (461 ± 259 receptors/platelet v 207 ± 99 receptors/platelet in seven normal controls; Table 2; P = .04).

Platelet kinetic measurements.

The immediate recovery of autologous 111In-labeled platelets in thrombocytopenic HIV-infected patients was decreased to 33 ± 16%, compared with 65 ± 5% in 20 normal controls (Table 2; P = .0001). The single patient exhibiting normal recovery of injected 111In-labeled autologous platelets (Table 2) is presumably explained by the absence of clinical splenomegaly (Table 1).

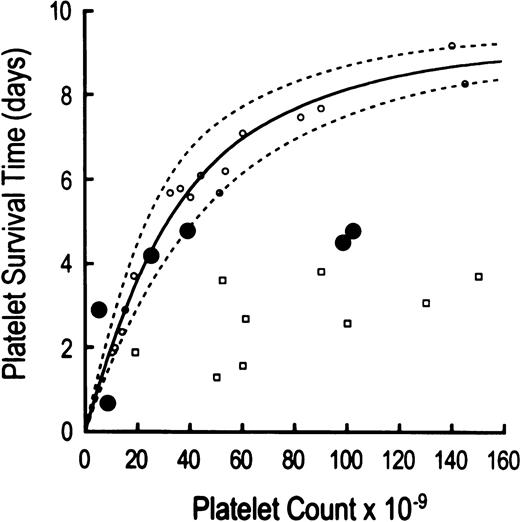

The life span of autologous 111In-platelets was shortened to 87 ± 39 hours in thrombocytopenic HIV-infected patients (P = .0001 compared with 232 ± 38 hours in 20 normal controls; Table 2). Compared to another group of patients with thrombocytopenia caused by megakaryocyte hypoplasia (Fig1), platelet life span measurements in three of the six thrombocytopenic HIV-infected patients were shortened according to the severity of the thrombocytopenia (Table 2, Fig 1). This concentration-dependent reduction in platelet life span has been attributed to increasing proportions of peripheral platelets undergoing utilization in maintaining platelet hemostatic function23,36 (Fig 1). At least two, and probably three, HIV-infected thrombocytopenic patients had reduced platelet life spans shorter than would have been predicted by the peripheral platelet counts, implicating immune-mediated platelet destruction as an extrinsic hazard, similar to patients with immune-mediated thrombocytopenia typical of immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP)23 (Fig 1). No identified clinical features were found to discriminate those patients with shorter platelet life spans than expected for the degree of thrombocytopenia from those with life spans appropriate for the degree of thrombocytopenia.

Relationship between autologous111In-platelet life span and peripheral platelet concentration. Platelet life span results are compared to peripheral platelet counts in three groups of thrombocytopenic patients: (1) six HIV-infected patients (depicted by large solid circles); (2) 17 patients with thrombocytopenia due to megakaryocytic hypoplasia (identified by open circles); and (3) nine patients with thrombocytopenia due to autoimmune destruction (clinical idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, ITP, shown by open squares). Three thrombocytopenic HIV-infected patients demonstrate concentration-dependent shortening of platelet life spans attributable to increased platelet utilization in maintaining platelet hemostatic function. By contrast, two thrombocytopenic HIV patients show shortening of platelet life span that is greater than expected on the basis of peripheral platelet counts per se, thereby implicating antiplatelet GPIIIa49-66Abs in the immune-mediated random destruction of platelets. The markedly shortened platelet life span in the sixth thrombocytopenic HIV-infected patient is also probably attributable to immune destruction, although the above comparison of platelet count to platelet life span does not clearly discriminate between hemostatic utilization versus immune destruction for platelet counts of less than 10,000 μL. The platelet life span data in patients with thrombocytopenia secondary to marrow hypoplasia and idiopathic thrombocytopenia represent results obtained from a prior report.23

Relationship between autologous111In-platelet life span and peripheral platelet concentration. Platelet life span results are compared to peripheral platelet counts in three groups of thrombocytopenic patients: (1) six HIV-infected patients (depicted by large solid circles); (2) 17 patients with thrombocytopenia due to megakaryocytic hypoplasia (identified by open circles); and (3) nine patients with thrombocytopenia due to autoimmune destruction (clinical idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, ITP, shown by open squares). Three thrombocytopenic HIV-infected patients demonstrate concentration-dependent shortening of platelet life spans attributable to increased platelet utilization in maintaining platelet hemostatic function. By contrast, two thrombocytopenic HIV patients show shortening of platelet life span that is greater than expected on the basis of peripheral platelet counts per se, thereby implicating antiplatelet GPIIIa49-66Abs in the immune-mediated random destruction of platelets. The markedly shortened platelet life span in the sixth thrombocytopenic HIV-infected patient is also probably attributable to immune destruction, although the above comparison of platelet count to platelet life span does not clearly discriminate between hemostatic utilization versus immune destruction for platelet counts of less than 10,000 μL. The platelet life span data in patients with thrombocytopenia secondary to marrow hypoplasia and idiopathic thrombocytopenia represent results obtained from a prior report.23

Calculated platelet mass turnover was 3.8 ± 1.5 × 105fL/μL/d, equivalent to 3.8 ± 0.41 × 105 fL/μL/d in normal controls (Table 2; P > .5).

Marrow megakaryocyte measurements.

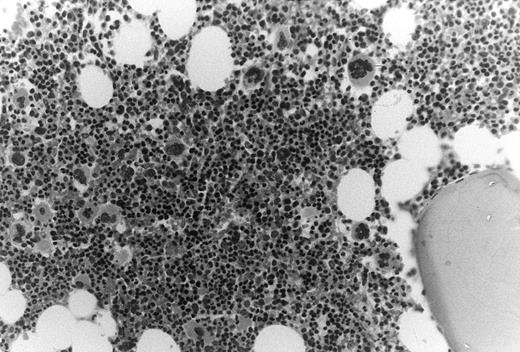

In these thrombocytopenic HIV-infected patients the number of marrow megakaryocytes was increased nearly threefold, ie, 30 ± 15 × 106/kg compared with 11 ± 2.1 × 106/kg (P = .02). Bone marrow biopsy specimens showed normal cellularity with increased ratios of morphologic megakaryocytes to nucleated erythroid cells (Fig 2).

Increased megakaryocytes in bone marrow biopsy samples obtained from HIV-infected patients with thrombocytopenia. In this cohort of thrombocytopenic HIV-infected patients bone marrow biopsy samples typically showed normal to abundant megakaryocytes; megakaryocyte/erythroid ratios were typically increased.

Increased megakaryocytes in bone marrow biopsy samples obtained from HIV-infected patients with thrombocytopenia. In this cohort of thrombocytopenic HIV-infected patients bone marrow biopsy samples typically showed normal to abundant megakaryocytes; megakaryocyte/erythroid ratios were typically increased.

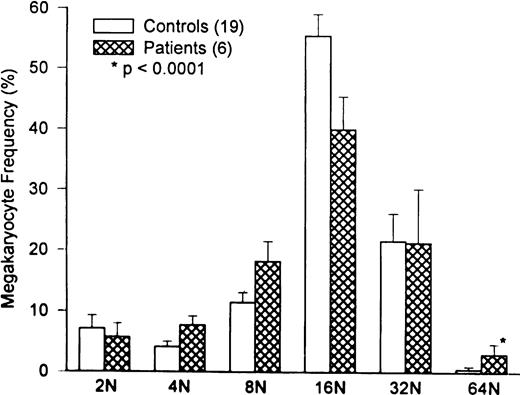

Marrow megakaryocyte volumes averaged 32 ± .9 × 103 fL (P = .05 compared with 28 ± 4.5 × 103 fL in 20 normal controls). Changes in megakaryocyte volume were caused by the relative increase in high-ploidy megakaryocytes (Fig 3;P = .0001).

Comparison of marrow megakaryocyte ploidy distribution for HIV-infected thrombocytopenic patients and normal subjects. The megakaryocyte ploidy distribution for 20 normal subjects is depicted by the open bars. The ploidy distribution of marrow megakaryocytes for six thrombocytopenic HIV patients is shown by the hatched bars. While there is a significant increase in 64N megakaryocytes in patients with HIV thrombocytopenia (P < .0001), the overall megakaryocyte ploidy is nearly normal, because of the increase in 4N and 8N cells at the expense of 16N cells. The ploidy distribution in HIV thrombocytopenic patients is interpreted to represent TPO-driven stimulation of megakaryocyte growth and development.

Comparison of marrow megakaryocyte ploidy distribution for HIV-infected thrombocytopenic patients and normal subjects. The megakaryocyte ploidy distribution for 20 normal subjects is depicted by the open bars. The ploidy distribution of marrow megakaryocytes for six thrombocytopenic HIV patients is shown by the hatched bars. While there is a significant increase in 64N megakaryocytes in patients with HIV thrombocytopenia (P < .0001), the overall megakaryocyte ploidy is nearly normal, because of the increase in 4N and 8N cells at the expense of 16N cells. The ploidy distribution in HIV thrombocytopenic patients is interpreted to represent TPO-driven stimulation of megakaryocyte growth and development.

The median marrow megakaryocyte progenitor cell number in marrow aspirates from HIV-infected thrombocytopenic patients was significantly decreased by an order of magnitude, averaging 3.3 (range, 0.4 to 7.3) CFU-Meg/1,000 CD34+ cells compared with 27 (range, 0.1 to 6.1) in thrombocytopenic HIV-infected patients (P = .02).

The mean marrow megakaryocyte mass, the product of megakaryocyte numbers and megakaryocyte volumes, was increased threefold, i.e., 93 ± 47 × 1010 fL/kg compared with normal control value of 31 ± 5.3 × 1010 fL/kg (P = .007). Despite this threefold expansion in megakaryocyte substrate available for platelet formation, there was no increase in the delivery of viable platelets to the peripheral blood (platelet mass turnover measurements compared with results in normal controls; Table 2).

DISCUSSION

This study in six HIV-infected patients with chronic thrombocytopenia shows that the low peripheral platelet counts were the result of a combination of reduced life span of platelets in the systemic circulation and enhanced sequestration of platelets in the splenic circulation, coupled with ineffective compensatory responses in platelet formation despite a threefold expansion in marrow megakaryocyte mass. This disparity between circulating platelet product and marrow platelet substrate may reflect impairment in platelet formation resulting from HIV-infected marrow megakaryocytes, or HIV-induced inhibitory cytokines.

Concordant with previous published reports,1,2,4,6,7,10antiplatelet GPIIIa49-66Ab were uniformly elevated in the sera of these thrombocytopenic HIV-infected patients (Table 2). However, no reciprocal relationship was observed between antiplatelet GPIIIa49-66Ab and peripheral platelet counts (Table 2). Shortened platelet survival times observed in thrombocytopenic HIV-infected patients have generally been attributed to immune platelet destruction induced by these antiplatelet GPIIIa49-66Abs directed against autologous platelet GPIIIa49-66immunodominant epitope, analogous to immune-mediated thrombocytopenia typical of ITP involving autoantibodies exhibiting gpIb/IX or gpIIb/IIIa specificity, or both.5 9 The present observations provide additional evidence that immune platelet destruction is dominant in some, but not all, patients (Fig 1).

Platelet life span was substantially decreased in all thrombocytopenic HIV-infected patients studied; on average, platelet survival time was reduced by approximately two thirds, compared with results obtained in normal control subjects (Table 2). At least two, and probably three, of the six HIV-thrombocytopenic patients demonstrated ITP-like immune platelet destruction mediated by antiplatelet antibodies5,23 (Fig 1, and Table 2). By contrast, three of the six patients convincingly demonstrated reductions in platelet life span characteristic of the degree of thrombocytopenia, per se, typical of the relationship between peripheral platelet counts and shortened platelet lifespan observed in patients with thrombocytopenia secondary to megakaryocyte hypoplasia23,36 (Fig 1). Accelerated platelet removal in these three patients was mediated by thrombocytopenia-dependent enhanced platelet utilization required to maintain platelet hemostatic function, as opposed to the antiplatelet antibody-mediated platelet removal typically occurring in patients with chronic ITP. We postulate that the shortening of platelet survival times reported by others may also reflect, at least in part, utilization secondary to thrombocytopenia.5,9,23 This interpretation assumes that circulating platelets may bear attached molecules of IgG without inducing significantly accelerated platelet removal, a well-documented observation.37

In the present study megakaryocyte number, volume and ploidy were quantified in aspirated marrow using flow cytometric analyses. This technique is well suited to measuring low-frequency cellular events in complex cell suspensions.27,29,30 Highly efficient DNA staining was combined with specific probes for megakaryocytes and erythroid forms, to obtain measurements of megakaryocyte size, ploidy, and number.29,30 Estimating the marrow megakaryocyte number depended on determining the ratio of marrow megakaryocytes to nucleated erythroid cells and assumed that erythropoiesis remained normal and constant. Relatively normal steady-state peripheral erythrocyte counts in these patients justifies that assumption (Table 1). This approach to megakaryocyte quantitation also presumes that GPIIb/IIIa-negative megakaryocyte progenitors do not constitute quantitatively important proportions of total marrow megakaryocytes. In this regard less than 5% of marrow megakaryocytes are sufficiently immature that they fail to express GPIIb/IIIa.32

Flow cytometric megakaryocyte quantitation documented a threefold expansion in marrow megakaryocyte substrate available for platelet production in these thrombocytopenic HIV-infected patients (Table 2). Estimates of increased megakaryocytopoiesis were also evident from the marrow biopsies (Fig 2). We attribute this amplification in marrow megakaryocyte mass to stimulation by endogenous TPO (Table 2), because endogenous TPO was significantly elevated in these patients (Table 2). However, the reduction in the number of marrow megakaryocyte progenitors in these patients implies a direct effect of HIV on megakaryocyte development (Table 2). The decreased frequency of megakaryocyte progenitors within the CD34+ population in the marrow of HIV-infected patients is comparable to the reduction in CFU-Megs found in the marrow of chemotherapy patients undergoing autologous bone marrow transplantation. This reduction in marrow progenitors may be due to inhibitory effects of HIV on the proliferation of marrow hematopoietic progenitor cells.

The increase in endogenous TPO levels was modest, similar to levels observed in ITP patients, a setting also characterized by enhanced thrombocytopoiesis.20,23 By contrast, patients with severe thrombocytopenia caused by marrow aplasia attain levels exceeding normal values by at least an order of magnitude.18-20 It is reasonable to speculate that the levels of free TPO in plasma may be less than that observed in marrow aplasia caused by removal by competitive binding of threefold increased TPO-receptor density on platelets undergoing normal turnover and threefold expanded marrow megakaryocyte cytoplasm. Presumably, the megakaryocytes also express threefold increased TPO-receptor density, since the increased TPO receptor density on platelets must have originated from higher TPO receptor-density marrow megakaryocytes (Table 2). Thus, the thrombocytopoietic stimulatory capacity of modestly elevated endogenous TPO levels in HIV-infected thrombocytopenic patients may be functionally equivalent to substantially greater circulating levels of TPO, per se, as a result of enhanced binding and augmented responsiveness of marrow megakaryocytes to free circulating TPO. Preclinical evidence in nonhuman primates also supports the notion that the increase in megakaryocytopoiesis is TPO driven by demonstrating that increases in megakaryocyte ploidy constituted early, sensitive, and quantitative morphologic indicators of TPO stimulation of megakaryocytopoiesis, and that full expansion in megakaryocyte number developed over weeks.1,5 9 Published results of marrow changes in patients receiving injections of exogenous TPO or PEGrHuMGDF report similar changes in megakaryocytes produced by comparably increased levels of cytokine.

We conclude that the elevated TPO levels in sera from HIV-thrombocytopenic patients are capable of stimulating thrombocytopoiesis sufficiently to compensate for the modest shortening in platelet life span and doubling of splenic pooling. The contrast between the threefold expansion in megakaryocyte substrate available for platelet formation and the unchanged normal platelet mass turnover (Table 2), represents a threefold disparity between marrow substrate and circulating product, a disorder known as ineffective production.

Thrombocytopenia in HIV-infected patients responds to antiviral therapy,38-40 implying that the low platelet counts in HIV-infected patients are directly related to HIV infection. In situ hybridization studies demonstrate HIV infection in marrow megakaryocytes from thrombocytopenic HIV patients. In addition, megakaryocytes in thrombocytopenic HIV patients frequently show morphologic abnormalities, including naked nuclei and broad peripheral cytoplasmic rims.41 Accelerated apoptosis also develops in megakaryocytes obtained from thrombocytopenic HIV patients, and the degree of programmed cell death was inversely proportional to the severity of thrombocytopenia.42 The present demonstration of a threefold disparity between marrow substrate and circulating product suggests that maturing marrow megakaryocytes may undergo HIV-induced apoptosis before platelet formation has been completed by prematurely dying megakaryocytes.

Thrombocytopenia in some HIV-infected patients also responds to immunosuppressive therapies similar to those used in managing patients with chronic ITP, including high-dose steroids, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), splenectomy, anti-D antibody, vincristine, danazol, and interferon.43 These observations are consistent with the present evidence implicating antiplatelet GPIIIa49-66Ab in the mechanism underlying platelet destruction in some patients, or at some stages in the course of their illness. Antiplatelet GPIIIa49-66Ab produced immune-mediated platelet destruction in at least two, and probably three of the six patients in this study (Fig 1, Table 2), and IVIG therapy transiently normalized their peripheral platelet counts. However, some immunosuppressive therapies may complicate the clinical course of AIDS. Because major bleeding seldom occurs in thrombocytopenic HIV patients despite prolonged low platelet counts, similar to the clinical course in chronic ITP patients, immune thrombocytopenia in HIV patients may need therapy only when confronted with some procedural, surgical, or traumatic event.44

Alternatively, peripheral platelet counts in thrombocytopenia in HIV patients may be successfully treated by pharmacologic hyperstimulation of megakaryocytopoiesis using PEG-rHuMGDF or rHuTPO. This possibility is supported by the recent observation that the administration of three twice-weekly doses of PEG-rHuMGDF to thrombocytopenic HIV-infected chimpanzees increased the peripheral platelet counts 10-fold without increasing HIV load.45 By contrast, other cytokines effecting monocyte proliferation, such as GM-CSF, M-CSF, and IL-3 have been shown to increase HIV replication in vitro.46

In summary, thrombocytopenia in HIV-infected patients results from decreased formation of viable platelets despite TPO-expanded megakaryocytopoiesis, together with accelerated platelet removal from the systemic circulation and increased platelet sequestration in the splenic circulation. We attribute the threefold disparity between marrow platelet substrate and circulating platelet product to impaired formation of platelets by HIV-infected megakaryocytes, or HIV-induced inhibitory cytokines. This formulation suggests that therapy with PEG-rHuMGDF may be useful in HIV-infected patients with chronic thrombocytopenia.

Supported in part by U.S. Public Health Service Grant No. MO1-RR-00039 from the GCRC program of the NIH NCRR and during a Clinical Research Fellowship (to J.L.C.) provided by Amgen, Inc, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Address reprint requests to Laurence A. Harker, MD, Division of Hematology and Oncology, Emory University, 1639 Pierce Dr, 1003 Woodruff Memorial Bldg, Atlanta, GA 30322.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal