Multiple myeloma is characterized by an accumulation of malignant plasma cells in the bone marrow coupled with an altered balance of osteoclasts and osteoblasts, leading to lytic bone disease. Although some of the cytokines driving this process have been characterized, little is known about the negative regulators. We show that syndecan-1 (CD 138), a heparan sulfate proteoglycan, expressed on and actively shed from the surface of most myeloma cells, induces apoptosis and inhibits the growth of myeloma tumor cells and also mediates decreased osteoclast and increased osteoblast differentiation. The addition of intact purified syndecan-1 ectodomain (1 to 6 nmol/L) to myeloma cell lines in culture leads to induction of apoptosis and dose-dependent growth inhibition, with concurrent downregulation of cyclin D1. The addition of purified syndecan-1 in picomolar concentrations to bone marrow cells in culture leads to a dose-dependent decrease in osteoclastogenesis and a smaller increase in osteoblastogenesis. In contrast to the effect on myeloma cells, the effect of syndecan-1 on osteoclastogenesis only requires the syndecan-1 heparan sulfate chains and not the intact ectodomain, suggesting that syndecan's effect on myeloma and bone cells occurs through different mechanisms. When injected in severe combined immune deficient (scid) mice, control-transfected myeloma cells (ARH-77 cells) expressing little syndecan-1 readily form tumors, leading to hind limb paralysis and lytic bone disease. However, after the injection of syndecan-1–transfected ARH-77 cells, the development of disease-related morbidity and lytic bone disease is significantly inhibited. Taken together, our data demonstrate, both in vitro and in vivo, that syndecan-1 has a significant beneficial effect on the behavior of both myeloma and bone cells and therefore may represent one of the central molecules in the regulation of myeloma pathobiology.

GROWTH OF TUMOR and normal cells in the tumor microenvironment is regulated by a balance between positive and negative regulators. Multiple myeloma (MM) is a B-cell malignancy characterized by the accumulation of malignant plasma cells in the bone marrow.1 A number of cytokines, including interleukin-6 (IL-6), the related gp 130 family, CD40 ligand, and insulin-like growth factor, have been shown to promote myeloma cell growth in vitro.2 However, little is known about the naturally occurring negative regulators of myeloma cell growth and survival in vivo. IL-4 and interferon γ inhibit the growth of myeloma cells in vitro, but these effects are indirect and are overcome by the addition of exogenous IL-6.3 4

Lytic bone destruction and osteoporosis is a characteristic feature of myeloma. Histo-morphometric studies suggest that abnormal bone remodeling is one of the earliest features of myeloma, and the development of lytic bone disease is due to an imbalance of bone cells with increased osteoclasts and decreased osteoblasts.5,6The interaction between tumor cells and the bone marrow microenvironment, including bone cells, although thought to be critical for myeloma pathogenesis, is poorly understood.7 Since the original description of osteoclast-activating factor (OAF) by Mundy et al,8 a number of cytokines, including IL-6, IL-1β, and tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), have been postulated to mediate the increased osteoclastogenic activity in myeloma.5 Recently, it was shown that myeloma cells upregulate IL-6 but downregulate osteocalcin production by an osteoblast cell line via cell-cell contact.9 However, it is not known if counter-regulatory bone-preserving factors exist in myeloma.

Syndecan-1 is a member of a family of cell surface transmembrane heparan sulfate (HS) proteoglycans.10 During murine B-cell development, syndecan-1 is expressed at the pre-B–cell stage, is lost in mature B cells, and is re-expressed strongly in the mature plasma cells.11 The expression of syndecan-1 by most primary myeloma cells and myeloma cell lines12 has been used for purification of myeloma cells from clinical samples.13,14Previous studies in our laboratory have shown that syndecan-1 mediates specific adhesion of myeloma cells to type I collagen, inhibits their invasion into type I collagen gels, and mediates cell-cell adhesion between myeloma cells.12 15-17 We now show that this proteoglycan is shed from the surface of myeloma cells in culture and that this shed syndecan-1 inhibits myeloma cell growth in vitro. In addition, syndecan-1 also affects bone cell differentiation; it increases osteoblast development and inhibits osteoclast formation in murine bone marrow cell cultures. These in vitro results are supported by our in vivo studies using scid mice injected with myeloma cells transfected with either vector only or syndecan-1. In these studies, the expression of syndecan-1 on myeloma cells is associated with an inhibition and delay in the development of myeloma-induced morbidity and decreased lytic bone disease. These data suggest that syndecan-1 forms part of a potentially beneficial regulatory loop that inhibits myeloma cell growth and bone loss in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Lines and Cell Culture

Myeloma cell lines (RPMI 8226 and ARH-77) were obtained from American Tissue Type Culture (ATCC; Rockville, MD) or derived at our institution from patients with myeloma (arp, ark, and mer; kindly provided by Dr J. Epstein, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences). Cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and 2 mmol L-glutamine. None of the cell lines used require the addition of IL-6 for growth. For scid mice experiments, syndecan-1–negative ARH-77 cells transfected with either a control vector carrying the neomycin resistance gene (ARH-77neo) or a full length syndecan-1 construct (ARH-77syn-1), as previously described,16 were used.

Detection of Syndecan-1 Shed Into the Conditioned Media

Immuno-dot blotting.

Shed syndecan-1 was partially purified using diethylaminoethyl (DEAE) chromatography followed by detection using immuno-dot blotting as previously described.12 Briefly, media conditioned by MM cells was brought to 2 mol/L urea and 50 mmol/L sodium acetate (pH 4.5). The medium was clarified by centrifugation at 15,000g for 10 minutes at 10°C. DEAE sepharose beads were added to the media and the mixture placed on a rocker for 1 hour at room temperature. DEAE beads were pelleted by gentle centrifugation (1,200 rpm for 7 minutes), placed in a clean 0.5-mL microcentrifuge tube, washed 4 times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) by centrifugation, and eluted with PBS containing 1 mol/L NaCl. The DEAE eluates were adjusted to a final NaCl concentration of 0.15 mol/L by dilution with 10 mmol/L Tris, pH 7.4. Samples were loaded on to Genetrans (Plasco Inc, Woburn, MA), a cationic nylon membrane using a immuno-dot blot apparatus (Miliblot D; Milipore, Bedford, MA). Membranes were removed from the apparatus and the remaining binding sites were blocked for 1 hour with a solution containing 3% nonfat dry milk, 0.5% bovine serum albumin, 10 mmol/L Tris, pH 8.0, 0.15 mol/L NaCl and 0.3% Tween-20. Blots were probed overnight at 4°C with a 1:100 dilution of an anti–syndecan-1 antibody B-B4 (Serotec Inc, Oxford, UK). After washing in PBS, blots were incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature with biotinylated goat antimouse secondary antibody, followed by incubation with Vectastain Elite ABC reagent in accordance with manufacturer's protocol (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), and visualized by diaminobenzidine as a substrate.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Western blotting.

Samples eluted from DEAE beads were desalted by passage over G-5 excellulose columns equilibrated with 0.1% SDS and run on 4% to 12% SDS-PAGE gels. For heparitinase digestion, before desalting, some samples were diluted to a concentration of 0.15 mol/L NaCl and incubated with 33 μIU/mL of Flavobacterium heparinum heparitin sulfate lyase (heparitinase; Seikagaku, Rockville, MD) for 30 minutes at 42°C, followed by another incubation for 30 minutes with 33 μIU/mL of heparitinase. After transfer of gels to a cationic nylon filter, syndecan-1 was detected, as described above.

Isolation of Syndecan-1 Ectodomain

Syndecan-1 ectodomain was purified from the conditioned media of ARH-77syn-1 cells. Sepharose beads conjugated to monoclonal antibody 281.2, specific for the murine syndecan-1 core protein,18 were blocked by preincubation with complete media and heparin (10 μg/mL) for 1 hour at room temperature and washed twice with PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100. Material eluted from DEAE as described above was added to 281.2-conjugated beads and incubated for 4 hours on a rocker at room temperature or 4°C overnight. Beads were washed twice with PBS with 0.25 mol/L NaCl and 0.1% Triton X-100 and transferred to a clean 0.5-mL microcentrifuge tube. Bound syndecan-1 was eluted using 50 mmol/L triethylamine (pH 11.5) and 0.1% Triton X-100 and the pH was immediately neutralized by addition of 1.0 mol/L Tris, pH 7.4. Purified syndecan-1 or, as a control, complete media (RPMI with 10% fetal calf serum) not conditioned by cells was passed over G-5 Excellulose columns (Pierce, Rockford, IL) equilibrated with complete medium. Syndecan-1 was quantitated by immunoblot analysis using I125-labeled antibody 281.2 and compared with purified syndecan-1 of known quantity (kindly provided by Dr M. Bernfield, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA). To determine if the intact syndecan-1 ectodomain was required for the biologic effect, in some experiments, purified and quantitated syndecan-1 was pretreated with 100 μIU/mL Flavobacterium heparinum heparitin sulfate lyase (heparitinase; Seikagaku) for 30 minutes at 42°C, followed by another 100 μIU/mL of heparitinase for additional 30 minutes. Glycosaminnoglycans (GAGs) from syndecan-1 ectodomain were generated using alkaline sodium borohydride, as previously described.15 In these experiments, intact ectodomain was used as a control.

Growth Inhibition Experiments

Myeloma cells (2 × 105 cells/mL) were incubated for 72 hours in complete medium containing various concentrations of syndecan-1 or control media, obtained as described above. Cell growth was determined by 3H-thymidine labeling and viable cell counting. Cell growth was expressed as a percentage of that seen in control media containing no exogenous syndecan-1.

Apoptosis, Cell Cycle Progression, and Cyclin D1 Expression

Induction of apoptosis by syndecan-1 ectodomain was determined with the TdT-mediated dUTP nick end-labeling (TUNEL) method, using a flow cytometry-based in situ cell death detection kit (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN) following the manufacturer's protocol. To determine the effect of syndecan-1 on cell cycle progression, DNA content of cells growing in log phase was analyzed using flow cytometry after propidium iodide (PI) staining. Cells (106) were incubated with media containing syndecan-1 or control media for 48 hours before fixation and DNA content analysis. Expression of cyclin D1 was determined by flow cytometry. Cells were fixed with alcohol and stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anticyclin D1 antibody (PharMingen, San Diego, CA), using the manufacturer's protocol. Cyclin D1 levels were expressed as the ratio of median fluorescent intensities of cells stained with cyclin D1 versus the isotype-matched control provided in the kit.

Osteoclast Formation in the Coculture System

The osteoblastic cell line (2107 cells), established from neonatal murine calvaria, was used in coculture assays for the evaluation of osteoclastogenesis as previously described.19 Briefly, murine marrow cells (2 × 105 cells per 500 μL) were cocultured with 40,000 calvaria cells for 8 days in the presence of 10 nmol/L 1,25(OH)2D3 with or without 1% (% volume) conditioned media from vector-transfected or syndecan-1–transfected myeloma cells. The number of osteoclasts was determined by counting tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP)-positive cells containing greater than 3 nuclei per cell.

Bone Marrow Cell Culture for Osteoclast and Osteoblast Differentiation

Bone marrow cell culture assays for the evaluation of osteoclastogenesis and osteoblastogenesis were performed as previously described.19,20 Briefly, bone marrow cells (106cells) from 8-week-old Swiss Webster male mice were cultured in 0.5 mL of α-Minimum Essential Medium (α-MEM) containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Sigma, St Louis, MO) in 24 multiwell dishes. After 8 days in culture, osteoclast- and osteoblast-like cell formation was examined, as previously described.19 1,25(OH)2D3 and/or purified syndecan-1 were added for the last 4 days of the total 8-day culture period. For osteoclast-like cell formation, the bone marrow cells (106) were cultured with 10−8 mol/L 1, 25(OH)2D3 alone or together with 0.65 pmol/L to 2 nmol/L syndecan-1 and stained for TRAP. For osteoblast-like cell formation, cells were cultured with 0.65 pmol/L to 2 nmol/L syndecan-1 and stained for alkaline phosphatase (ALP). Cells staining positive for TRAP (only those with >3 nuclei, representing osteoclasts) or colonies containing ALP-positive cells (representing osteoblasts) were counted under a light microscope using 200× magnification.

SCID Mice Experiments

Female CB.17/Icr-severe combined immune deficient (scid) mice, 6 to 8 weeks old, were obtained from Harlan Bioproducts for Science (Indianapolis, IN). They were housed and monitored as required in our animal facility, and the experiments were performed according to the protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Irradiated mice (150 cGy) were injected with 3 × 106 ARH-77syn-1 or ARH-77neo cells via the lateral tail vein. Successful transplantation was determined and monitored by measuring the human κ chain content of sera beginning weekly after day 7. The animals were euthanised when hind limb paralysis occurred, when large visible/palpable tumors were observed, or when animals appeared morbid, as determined by extreme emaciation and lethargy. Development of lytic bone lesions was determined by evaluation of whole body skeletal radiographs in a blinded fashion after the mice were sacrificed.

Statistical Analysis

The Student's t-test was used for comparison of various experimental groups, and significance was set at P < .05.

RESULTS

Syndecan-1 Is Expressed and Shed by Myeloma Cell Lines

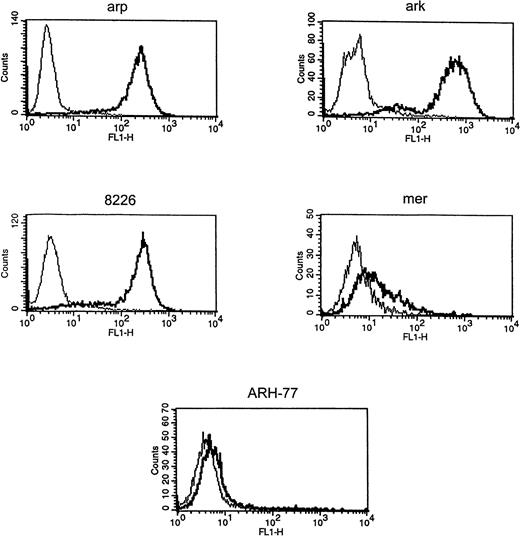

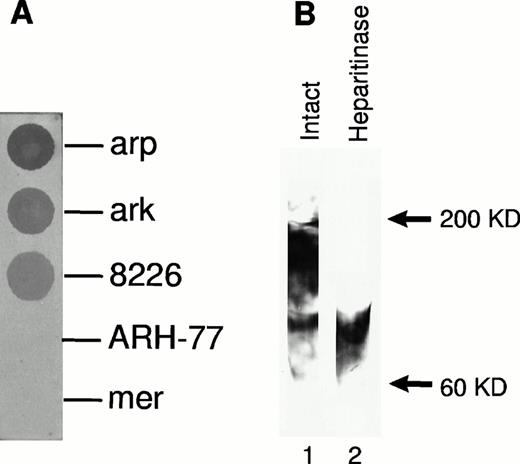

Expression of cell surface syndecan-1 on myeloma cell lines was examined by flow cytometry using anti-syndecan-1 antibody B-B4. As shown in Fig 1, arp, ark, and RPMI 8226 cells strongly express cell surface syndecan-1. Syndecan-1 expression in mer cells is significantly lower, whereas ARH-77 cells have only very faint expression of syndecan-1 (Fig 1). The sensitivity of flow cytometric detection is thus higher than the previously reported immuno-dot blot analysis of cell lysates in which syndecan-1 could not be detected in ARH-77 and mer cells and was weakly expressed in RPMI 8226 cells.12 To determine if syndecan-1 is shed from the tumor cell surface, media conditioned by these cells were analyzed by an immuno-dot blot assay. Shed syndecan-1 is detected in the conditioned media of all three cell lines that highly express cell surface syndecan-1 (arp, ark, and RPMI 8226), but not in conditioned media from ARH-77 or mer cells (Fig 2A). Syndecan-1 ectodomain shed by myeloma cells migrates on Western blots as a broad smear that is reduced to a narrow smear just above 60 kD after treatment with heparitinase (Fig 2B), indicating that the syndecan-1 ectodomain is shed as an intact molecule bearing predominantly heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycan (GAG) chains. Intact syndecan-1 ectodomain is also shed by ARH-77 cells engineered to express syndcecan-1 (ARH-77syn-1; Liu et al, unpublished data). The level of shed syndecan-1 ectodomain in the myeloma cell conditioned media is dependent on a number of variables, including cell density, length of culture, and cell surface expression, but can reach 1 to 2 nmol/L concentration.

Expression of syndecan-1 by myeloma cell lines. Myeloma cell lines (ark, arp, RPMI-8226, mer, and ARH-77) were stained with FITC-labeled anti–syndecan-1 antibody (B-B4) (thick line) or isotype control (thin line), and fluorescence intensity was analyzed using flow cytometry.

Expression of syndecan-1 by myeloma cell lines. Myeloma cell lines (ark, arp, RPMI-8226, mer, and ARH-77) were stained with FITC-labeled anti–syndecan-1 antibody (B-B4) (thick line) or isotype control (thin line), and fluorescence intensity was analyzed using flow cytometry.

Syndecan-1 ectodomain is shed from the surface of myeloma cell lines. (A) Presence of shed syndecan-1 ectodomain in the media conditioned by myeloma cell lines. Syndecan-1 was detected using an immuno-dot blot analysis with anti–syndecan-1 antibody (B-B4). (B) Western blot of partially purified syndecan-1 from media conditioned by ark cells probed with B-B4, showing the presence of intact syndecan-1 ectodomain and ectodomain after digestion with heparitinase.

Syndecan-1 ectodomain is shed from the surface of myeloma cell lines. (A) Presence of shed syndecan-1 ectodomain in the media conditioned by myeloma cell lines. Syndecan-1 was detected using an immuno-dot blot analysis with anti–syndecan-1 antibody (B-B4). (B) Western blot of partially purified syndecan-1 from media conditioned by ark cells probed with B-B4, showing the presence of intact syndecan-1 ectodomain and ectodomain after digestion with heparitinase.

Shed Syndecan-1 Inhibits the Growth of Myeloma Cell Lines In Vitro

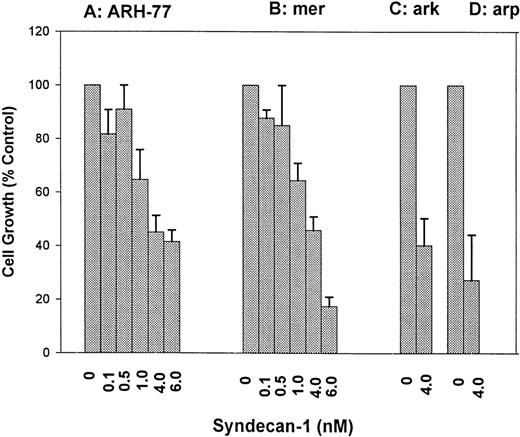

ARH-77 and mer cells that express and shed little or no syndecan-1 were incubated with various concentrations of purified syndecan-1 for 72 hours. Cell growth was determined using 3H-thymidine proliferation assays, and similar data were obtained using cell counting (not shown). The addition of syndecan-1 at nanomolar concentrations inhibits the growth of both cell lines in a dose-dependent fashion (Fig 3A and B). This growth-inhibitory effect is not limited to syndecan-1–negative cells, because a similar growth-inhibition is seen in ark and arp cells that express and shed syndecan-1 (Fig 3C and D). Thus, shed syndecan-1 is able to inhibit the growth of all myeloma cell lines tested, regardless of whether they express cell surface syndecan-1.

Dose-dependent inhibition of myeloma cell growth by syndecan-1 ectodomain. (A) ARH-77 cells; (B) mer cells; (C) ark cells; (D) arp cells. Effect of addition of purified syndecan-1 ectodomain on the growth of myeloma cell lines (ARH-77, mer, arp, and ark) in culture. Cells (3 × 104) were incubated with various concentrations of syndecan-1 or in media alone for 72 hours, and cell growth was analyzed by 3H-thymidine proliferation assays. Cell growth is expressed as a percentage of control (media only).

Dose-dependent inhibition of myeloma cell growth by syndecan-1 ectodomain. (A) ARH-77 cells; (B) mer cells; (C) ark cells; (D) arp cells. Effect of addition of purified syndecan-1 ectodomain on the growth of myeloma cell lines (ARH-77, mer, arp, and ark) in culture. Cells (3 × 104) were incubated with various concentrations of syndecan-1 or in media alone for 72 hours, and cell growth was analyzed by 3H-thymidine proliferation assays. Cell growth is expressed as a percentage of control (media only).

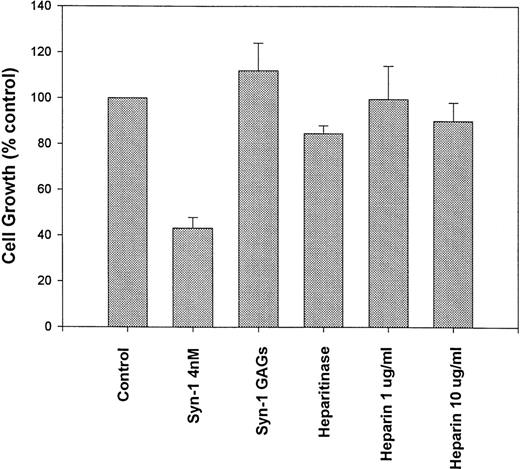

Pretreatment of purified syndecan-1 with heparitinase (to remove the HS chains), largely abolishes the growth-inhibitory activity, suggesting that the presence of HS chains is essential for this effect (Fig 4). This finding also suggests that the growth inhibition is due to the syndecan-1 ectodomain and not due to an impurity copurifying in association with GAG chains. Growth of syndecan-1–negative ARH-77 cells was not altered in media pretreated with heparitinase, indicating that heparitinase was not mediating its effect through modification of other HS containing proteins in the system (not shown). The addition of either heparin alone (up to 10 μg/mL) or GAG chains isolated from purified syndecan-1 fails to significantly inhibit myeloma cell growth. Thus, the inhibition of myeloma cell growth by syndecan-1 requires an intact ectodomain.

Syndecan-1–mediated growth inhibition requires an intact proteoglycan. ARH-77 cells were incubated with intact purified syndecan-1 ectodomain (4 nmol/L), syndecan-1 (4 nmol/L) pretreated with heparitinase (Heparitinase), glycosaminoglycan (GAGs) chains purified from syndecan-1, or heparin (1 and 10 μg/mL) or in media alone (as control) for 72 hours. Cell growth is expressed as a percentage of control.

Syndecan-1–mediated growth inhibition requires an intact proteoglycan. ARH-77 cells were incubated with intact purified syndecan-1 ectodomain (4 nmol/L), syndecan-1 (4 nmol/L) pretreated with heparitinase (Heparitinase), glycosaminoglycan (GAGs) chains purified from syndecan-1, or heparin (1 and 10 μg/mL) or in media alone (as control) for 72 hours. Cell growth is expressed as a percentage of control.

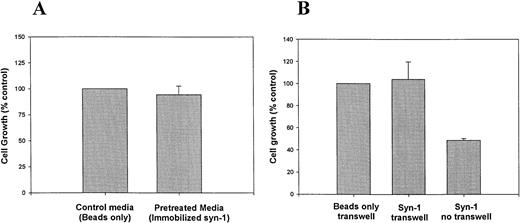

To evaluate the possibility that the growth inhibition is due to depletion of growth factors that bind to syndecan-1 HS chains, myeloma cells were grown in culture media preincubated with syndecan-1 immobilized on sepharose beads via the core protein, leaving the HS chains free to interact with potential ligands.21 Normal growth of cells in this pretreated media suggests that syndecan-1 does not exert its effects by depleting the media of growth factors (Fig 5A). Likewise, upon physical separation of myeloma cells in transwell inserts from immobilized syndecan-1, the cell growth is not inhibited (Fig 5B). Taken together, these data suggest that the inhibitory effect requires close proximity of syndecan-1 to the cell surface. Addition of IL-6 (10 ng/mL) at a concentration known to inhibit dexamethasone-mediated growth-inhibition and apoptosis22 fails to reverse the growth-inhibitory effect of syndecan-1 (data not shown).

Inhibition of growth requires close proximity of syndecan-1 to the cell surface. (A) Effect of media preincubated with immobilized syndecan-1 on myeloma cell growth. ARH-77 cells were grown in media preincubated with syndecan-1 immobilized on sepharose beads or beads only (as control). Cell growth is expressed as a percentage of control. (B) Transwell assay. ARH-77 cells were grown in transwell inserts, physically separated from syndecan-1 (4 nmol/L) immobilized on sepharose beads, or beads only (as control) in the lower wells. Cells grown in the absence of a transwell but with exogenous, soluble syndecan-1 (4 nmol/L) serve as a positive control (Syn-1 no transwell). Cell growth is expressed as a percentage of control.

Inhibition of growth requires close proximity of syndecan-1 to the cell surface. (A) Effect of media preincubated with immobilized syndecan-1 on myeloma cell growth. ARH-77 cells were grown in media preincubated with syndecan-1 immobilized on sepharose beads or beads only (as control). Cell growth is expressed as a percentage of control. (B) Transwell assay. ARH-77 cells were grown in transwell inserts, physically separated from syndecan-1 (4 nmol/L) immobilized on sepharose beads, or beads only (as control) in the lower wells. Cells grown in the absence of a transwell but with exogenous, soluble syndecan-1 (4 nmol/L) serve as a positive control (Syn-1 no transwell). Cell growth is expressed as a percentage of control.

Syndecan-1 Mediates Apoptosis and Affects G1-S Progression in Myeloma Cells

The addition of purified syndecan-1 ectodomain at concentrations ≥2 nmol/L leads to an induction of apoptosis of myeloma cells as determined by TdT mediated dUTP end labeling (TUNEL) assay (Fig 6A through D). This induction of apoptosis is seen both with syndecan-1–nonexpressing (ARH-77) and syndecan-1–expressing (arp) cells. The degree of apoptosis was somewhat higher in arp cells (which are also more sensitive to dexamethasone22 and melphalan) than in ARH-77 cells.

Induction of apoptosis of myeloma cells by syndecan-1. Myeloma cell lines ([A] and [B] ARH-77 cells; [C] and [D], arp cells) were incubated with media alone (A and C) or purified syndecan-1 (4 nmol/L) for 48 hours (B and D). Apoptosis was examined using flow cytometry-based TUNEL (TdT-mediated dUTP nick end labeling) assay (Boehringer Mannheim) using the manufacturer's protocol. For negative control (thin line), cells were stained with label solution in the absence of TdT. For test sample (thick line), cells were stained with TUNEL reaction mixture according to manufacturer's protocol. The apoptotic population is marked by an arrow. Figures represent one of three representative experiments.

Induction of apoptosis of myeloma cells by syndecan-1. Myeloma cell lines ([A] and [B] ARH-77 cells; [C] and [D], arp cells) were incubated with media alone (A and C) or purified syndecan-1 (4 nmol/L) for 48 hours (B and D). Apoptosis was examined using flow cytometry-based TUNEL (TdT-mediated dUTP nick end labeling) assay (Boehringer Mannheim) using the manufacturer's protocol. For negative control (thin line), cells were stained with label solution in the absence of TdT. For test sample (thick line), cells were stained with TUNEL reaction mixture according to manufacturer's protocol. The apoptotic population is marked by an arrow. Figures represent one of three representative experiments.

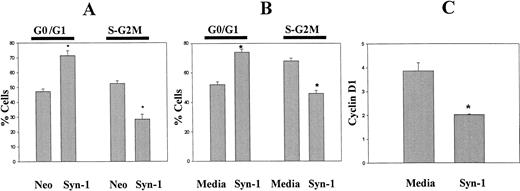

Cell cycle analysis of exponentially growing ARH-77 cells transfected with the cDNA for syndecan-1 (ARH-77syn-1) or the neo gene only (ARH-77neo) demonstrates that syndecan-1 expression inhibits G1-S transition (Fig 7A). A similar effect was seen upon the addition of purified syndecan-1 ectodomain to ARH-77 cells (Fig 7B). The delay at the G1-S progression by syndecan-1 is further supported by the downregulation of cyclin D1 upon the addition of purified syndecan-1 to ARH-77 cells (Fig 7C). Taken together, these data indicate that syndecan-1 may affect the growth and survival of myeloma cells by inducing apoptosis and downregulating cyclin D1 expression.

Effect of syndecan-1 on cell cycle progression and cyclin D1 expression. (A) Expression of syndecan-1 inhibits G1-S progression: DNA content of exponentially growing ARH-77 cells, transfected with vector only (ARH-77neo) or syndecan-1 (ARH-77syn-1), was determined by flow cytometry after PI staining. (B) Shed syndecan-1 inhibits G1-S progression: ARH-77 cells were incubated with syndecan-1 (2 nmol/L) or media alone for 48 hours and stained with PI. DNA content analysis was performed using flow cytometry. (C) Shed syndecan-1 inhibits cyclin D1 expression. ARH-77 cells were incubated with syndecan-1 (2 nmol/L) or media alone for 48 hours and stained for cyclin D1 using FITC-conjugated anti-cyclin D1 antibody using the manufacturer's protocol (PharMingen). Expression of cyclin D1 is expressed as the ratio of median fluorescent intensity of test sample to that of isotype control (*P < .05).

Effect of syndecan-1 on cell cycle progression and cyclin D1 expression. (A) Expression of syndecan-1 inhibits G1-S progression: DNA content of exponentially growing ARH-77 cells, transfected with vector only (ARH-77neo) or syndecan-1 (ARH-77syn-1), was determined by flow cytometry after PI staining. (B) Shed syndecan-1 inhibits G1-S progression: ARH-77 cells were incubated with syndecan-1 (2 nmol/L) or media alone for 48 hours and stained with PI. DNA content analysis was performed using flow cytometry. (C) Shed syndecan-1 inhibits cyclin D1 expression. ARH-77 cells were incubated with syndecan-1 (2 nmol/L) or media alone for 48 hours and stained for cyclin D1 using FITC-conjugated anti-cyclin D1 antibody using the manufacturer's protocol (PharMingen). Expression of cyclin D1 is expressed as the ratio of median fluorescent intensity of test sample to that of isotype control (*P < .05).

Syndecan-1 Inhibits Osteoclastogenesis and Promotes Osteoblastogenesis In Vitro

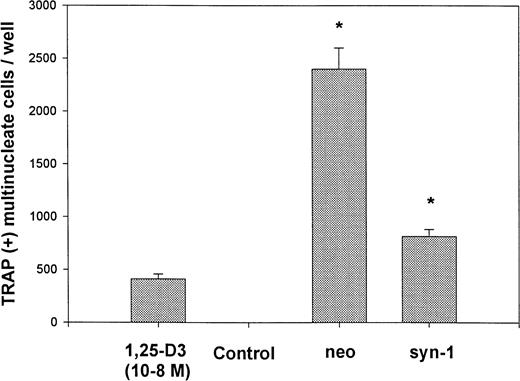

Osteoclast activation and recruitment are a characteristic feature of myeloma, and supernatants from myeloma cell lines have been shown to promote osteoclast differentiation in vitro.8 In initial screening experiments using a previously described bone marrow-calvarial coculture assay,19 media from control-transfected myeloma cells promote a marked increase in the number of osteoclasts as expected, whereas the addition of media from syndecan-1–transfected cells leads to significantly less stimulation of osteoclasts (Fig 8). Larger amounts of media led to further decrease in osteoclast formation (data not shown). These data suggest the presence of an inhibitor of osteoclastogenesis in the media conditioned by syndecan-1–transfected cells (versus neo-transfected cells).

Media from syndecan-1–expressing cells inhibit osteoclast formation in coculture assay. Marrow cells were cocultured with calvaria cells for 8 days in the absence (control) or presence of 10 nmol/L 1,25(OH)2D3, or 1 μL of conditioned media from vector-transfected (neo) or syndecan-1–transfected (syn-1) myeloma cells. The number of osteoclasts was determined by counting TRAP-positive cells with greater than 3 nuclei per cell (*P < .05).

Media from syndecan-1–expressing cells inhibit osteoclast formation in coculture assay. Marrow cells were cocultured with calvaria cells for 8 days in the absence (control) or presence of 10 nmol/L 1,25(OH)2D3, or 1 μL of conditioned media from vector-transfected (neo) or syndecan-1–transfected (syn-1) myeloma cells. The number of osteoclasts was determined by counting TRAP-positive cells with greater than 3 nuclei per cell (*P < .05).

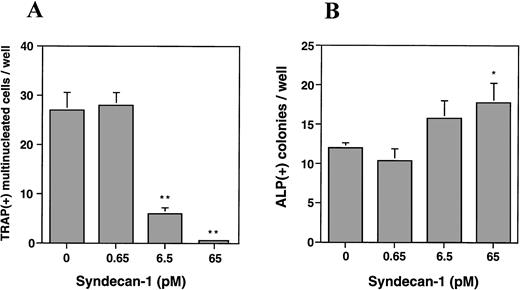

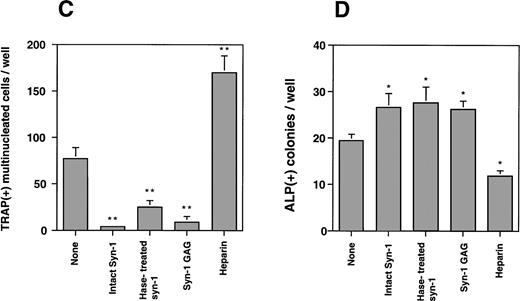

To further characterize this effect and to determine the effect on osteoblasts, we utilized a murine bone marrow cell culture assay and examined the effect of purified syndecan-1 on both osteoclastogenesis and osteoblastogenesis. The addition of syndecan-1 ectodomain leads to a significant dose-dependent decrease in multinucleate TRAP-positive cells (representing osteoclasts) and a modest increase in ALP-positive cells (representing osteoblasts; Fig 9A and B, respectively). The effect of syndecan-1 ectodomain on bone cell development was observed even at picomolar concentrations that have no effect on myeloma cell growth. Interestingly, in direct contrast to the effect on myeloma cells, the inhibition of osteoclastogenesis and stimulation of osteoblastogenesis by syndecan-1 does not require an intact ectodomain, because a similar effect was seen with syndecan-1 pretreated with heparitinase and with GAGs purified from syndecan-1 ectodomain (Fig 9C and D). However, this effect was specific for syndecan-1, because the addition of heparin (1 μg/mL) leads to an increase in osteoclastogenesis and inhibition of osteoblastogenesis in this assay.

Effect of syndecan-1 on multinucleate (> 3 nuclei) TRAP-positive and ALP-positive cell formation in murine bone marrow cultures. Bone marrow cells (106 cells/well) were cultured in α-MEM containing media in multiwell dishes for a total of 8 days. (A) Syndecan-1 inhibits osteoclastogenesis: Either 10−8mol/L 1,25(OH)2D3 alone or 10−8mol/L 1,25(OH)2D3 with 0.65 to 65 pmol/L syndecan-1 purified by immunoaffinity chromatography was added during the last 4 days in the culture period and cells were stained for TRAP. One of three representative experiments is shown. (B) Syndecan-1 promotes osteoblastogenesis: 0.65 to 65 pmol/L syndecan-1 was added during the last 4 days in the culture period and cells were stained for ALP. One of three representative experiments is shown. (C) Inhibition of osteoclast development by syndecan-1 does not require the intact syndecan ectodomain. Purified intact syndecan-1 ectodomain (45 pmol/L), syndecan-1 pretreated with heparitinase (Hase), purified syndecan-1 GAGs, or heparin (1 μg/mL) was added for the last 4 days in the culture period and cells were stained for TRAP. (D) Promotion of osteoblast development by syndecan-1 does not require the intact syndecan ectodomain. Purified intact syndecan-1 ectodomain (45 pmol/L), syndecan-1 pretreated with heparitinase (Hase), GAGs purified from syndecan-1, or heparin (1 μg/mL) was added for the last 4 days in the culture period and cells were stained for ALP (*P < .05; **P < .01).

Effect of syndecan-1 on multinucleate (> 3 nuclei) TRAP-positive and ALP-positive cell formation in murine bone marrow cultures. Bone marrow cells (106 cells/well) were cultured in α-MEM containing media in multiwell dishes for a total of 8 days. (A) Syndecan-1 inhibits osteoclastogenesis: Either 10−8mol/L 1,25(OH)2D3 alone or 10−8mol/L 1,25(OH)2D3 with 0.65 to 65 pmol/L syndecan-1 purified by immunoaffinity chromatography was added during the last 4 days in the culture period and cells were stained for TRAP. One of three representative experiments is shown. (B) Syndecan-1 promotes osteoblastogenesis: 0.65 to 65 pmol/L syndecan-1 was added during the last 4 days in the culture period and cells were stained for ALP. One of three representative experiments is shown. (C) Inhibition of osteoclast development by syndecan-1 does not require the intact syndecan ectodomain. Purified intact syndecan-1 ectodomain (45 pmol/L), syndecan-1 pretreated with heparitinase (Hase), purified syndecan-1 GAGs, or heparin (1 μg/mL) was added for the last 4 days in the culture period and cells were stained for TRAP. (D) Promotion of osteoblast development by syndecan-1 does not require the intact syndecan ectodomain. Purified intact syndecan-1 ectodomain (45 pmol/L), syndecan-1 pretreated with heparitinase (Hase), GAGs purified from syndecan-1, or heparin (1 μg/mL) was added for the last 4 days in the culture period and cells were stained for ALP (*P < .05; **P < .01).

Syndecan-1 Inhibits Myeloma-related Morbidity in scid Mice

A scid mouse model, previously well characterized for myeloma cell growth and bone disease,23 24 was used to examine whether syndecan-1 affected myeloma pathobiology in vivo. In this model, injection of ARH-77 cells into scid mice results in the development of myeloma-related morbidity in most mice, defined as hind limb paralysis due to spinal cord compression, visible soft tissue tumors, or extreme emaciation and lethargy. Irradiated C.B-17scid mice were injected with either ARH-77syn-1 or ARH-77neo cells via the lateral tail vein. The majority of the mice injected with the syndecan-1–negative ARH-77neocells developed overt disease and lytic bone lesions (Fig 10), thereby replicating the results obtained by other investigators using this cell line. However, after transfection of ARH-77 cells with syndecan-1, the development of myeloma-related morbidity as defined earlier was significantly inhibited (35% v 85%, P < .01) and delayed (mean time to morbidity 84 days v 58 days, P < .01) relative to control mice injected with the neo-transfected cells (Table 1). Furthermore, only 30% of mice injected with ARH-77syn-1 cells developed lytic bone disease, compared with 80% in controls (P < .05; Table 1).

Radiologic examination of mice injected with ARH-77 cells. Note the presence of lytic bone lesions at the proximal tibia and ilium (arrows) in a representative mice.

Radiologic examination of mice injected with ARH-77 cells. Note the presence of lytic bone lesions at the proximal tibia and ilium (arrows) in a representative mice.

Syndecan-1 Expression Inhibits the Development of Myeloma-Induced Morbidity in scid Mice

| Cells . | N . | Morbidity (%)-150 . | Mean Time to Morbidity . | Lytic Lesions (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARH-77neo | 20 | 85 | 58 d | 80 |

| ARH-77syn-1 | 20 | 35-151 | 84 d-151 | 30-151 |

| Cells . | N . | Morbidity (%)-150 . | Mean Time to Morbidity . | Lytic Lesions (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARH-77neo | 20 | 85 | 58 d | 80 |

| ARH-77syn-1 | 20 | 35-151 | 84 d-151 | 30-151 |

Male CB.17 scid mice were injected with ARH-77 cells transfected with either a control vector or full-length syndecan-1 construct and monitored for the development of disease-related morbidity. Development of lytic bone disease was evaluated with skeletal radiographs.

Defined as hind limb paralysis, visible tumors, or extreme emaciation and lethargy.

Statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

Results from the present work support the conclusion that syndecan-1 plays a major role in regulating the pathobiology of myeloma. First, we provide evidence that syndecan-1 is shed from the surface of myeloma cells as an intact ectodomain, and this shed syndecan-1 leads to a striking induction of apoptosis and inhibition of cell growth in vitro. Second, we show that syndecan-1 ectodomain may also affect the cells in the tumor microenvironment by inhibiting osteoclast and promoting osteoblast differentiation. Third, we demonstrate that, when myeloma cells are engineered to express syndecan-1 on their surface and then injected into scid mice, tumor development and disease-related morbidity is retarded relative to their syndecan-1–negative counterparts. Taken together with our previous studies showing that syndecan-1 is highly expressed by most malignant plasma cells12,13 and that cell surface syndecan-1 mediates both cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix adhesion and inhibits the invasion of cells through type I collagen,12,13,16 17 we conclude that syndecan-1, in both the cell surface and shed form, may play an important role in regulating the progression of this disease.

To our knowledge, this is the first report that an HS proteoglycan can induce cellular apoptosis. The mechanism of this striking induction of apoptosis of myeloma cells mediated by syndecan-1 is not known and may involve interaction of heparan sulfate chains with a cellular receptor17 or growth factor, with resultant modulation of growth factor signaling.25 In addition, the observation that different myeloma cell lines show differing levels of apoptosis in response to syndecan-1 (Fig 6) suggests that the extent of syndecan-1–induced apoptosis may be modulated by other factors (eg, endogenous levels of bcl-2). Induction of apoptosis by syndecan-1 may not be restricted to malignant cells, because it was recently shown that the presence of in situ apoptosis in the extrafollicular foci of antibody forming cells in the spleen correlated with the expression of high levels of syndecan-1.26

In addition to inducing apoptosis, purified syndecan-1 also induces an inhibition of G1-S progression and downregulation of cyclin D1. The fact that this growth-inhibitory effect requires the intact ectodomain, is not induced by heparin and requires close contact of syndecan-1 with the cells suggests that a specific interaction between syndecan-1 and the cell surface may be occurring. In sharp contrast to some other myeloma growth inhibitors (eg, dexamethasone, IL-4, and γ-interferon), exogenous IL-6 failed to reverse the syndecan-1–mediated effect,4,22 suggesting that the growth inhibition by syndecan-1 differs from these inhibitors in its mechanism of action. Similar to what we observe in myeloma, a growth-inhibitory effect of the intact syndecan-1 ectodomain has also been noted in carcinoma cells but not in normal epithelial cells.27However, in contrast to our observations, these investigators indicate that suppression of carcinoma growth was not associated with induction of apoptosis, suggesting that myeloma and carcinoma cells may differ in their response to syndecan-1. Interestingly, elevated levels of syndecan-1 promote the growth of the transformed renal epithelial cell line (293 T cells).28 Thus, the effect of syndecan-1 may vary between different cell types. The growth-regulatory effect of proteoglycans is not limited to syndecan-1. Recently, it was shown that the expression of perlecan, a basement membrane HS proteoglycan, was associated with a decrease in growth and invasiveness of fibrosarcoma cells.29 Negative growth regulation by the secreted chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan, decorin, has been attributed to its ability to bind transforming growth factor-β and upregulate cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21.30 Although the molecular mechanism of syndecan-1–mediated growth suppression is not known, it may similarly upregulate p21, leading to downregulation of cyclin D1 expression and to apoptosis, as we have observed.

Because syndecan-1 is shed from the surface of myeloma cells, it is potentially capable of exerting both a paracrine and systemic effect in myeloma patients. Clearly, the concentration of syndecan-1 ectodomain in vivo in the bone marrow microenvironment is important to syndecan-1–mediated paracrine effects in patients. In this regard, we have recently discovered that markedly elevated levels of intact syndecan-1 ectodomain are present in the serum of some myeloma patients.31 Moreover, shed syndecan-1 could be the source of the heparin-like anticoagulant occasionally responsible for coagulopathy in myeloma.32 Recently, it was shown that the shedding of syndecan-1 by cultured endothelial cells is highly regulated by the activation of at least two distinct receptor classes, G protein-coupled and protein tyrosine kinase,33 suggesting that shed syndecan-1 may have important regulatory roles in vivo. The regulation of shedding of syndecan-1 by myeloma cells and the clinical importance of serum syndecan-1 in myeloma patients remains to be examined.

In addition to its effects on myeloma cell growth, syndecan-1 also exerts significant effects on both osteoclast and osteoblast development in vitro and therefore may form part of a bone-preserving regulatory loop in myeloma. To our knowledge, these data represent the first evidence that syndecans may affect the development of bone cells. In sharp contrast to the effects on myeloma cells, the effect of syndecan-1 on bone cell development occurs at much lower (picomolar) concentrations and does not require an intact ectodomain, suggesting a different mechanism of action. The finding that heparitinase treatment does not abolish syndecan-1 effect suggests that fragments of syndecan-1 GAG may exert biological activity on bone cell precursors. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that this effect is due to growth-regulatory factors that are bound to the purified syndecan-1 HS chains and remain active after heparitinase digestion. The in vitro effects on bone cell development are further supported by the in vivo data showing diminished lytic bone disease in mice injected with syndecan-1–expressing cells. However, whether the observed reduction in lytic bone disease is due to a direct effect of syndecan-1 on bone or via tumor bulk reduction is not addressed in this study.

The finding that syndecan-1 may have a beneficial effect on bone is surprising, because bone loss is a well-recognized complication of heparin therapy.34 Our finding that heparin leads to an increase in osteoclastogenesis and inhibition of osteoblastogenesis in vitro is consistent with prior in vivo observations that heparin promotes osteoclast-mediated bone resorption35 and inhibits osteoblast formation36 and may be the mechanism of heparin's effect on bone. Recent studies have shown that the osteopenic effect is dependent on both size and sulfation of the heparin fragments and is less with low molecular weight heparin than with unfractionated heparin.35,36 Thus, the effect of various heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPG) on the bone may differ, depending on the nature and fine structure of GAGs. Indeed, HSPGs have been shown to bind a number of cytokines and soluble factors with ability to both stimulate or inhibit osteoclasts and osteoblasts in vitro.37,38 Syndecan-1 is expressed transiently during mammalian tooth development and may play an important role in this process.39 Expression of syndecan-1 and bone morphogenetic protein-4 is specifically reduced in the dental mesenchyme with mutant Msx1, a member of Msx homeobox family, critical for tooth morphogenesis and craniofacial development.40 Taken together with the data presented in this report, these observations suggest that HSPGs, including syndecan-1, may play an important role in the regulation of bone formation in vivo and that the nature of this regulation may depend on the specific GAG structure and nature of the proteoglycan.

In summary, we have shown that syndecan-1 has a significant impact on the behavior of cells in the tumor microenvironment in myeloma, both in vitro and in vivo. It may therefore constitute part of a potentially beneficial regulatory loop to counteract the net effect of other molecules (eg, IL-6) that promote myeloma cell proliferation/survival and bone loss. Further understanding of the mechanism and regulation of these biologic effects may lead to novel therapies for myeloma. These data also have obvious implications for improved therapy of other hematologic (eg, Hodgkin's disease and primary effusion lymphoma)41,42 or epithelial malignancies (eg, laryngeal cancer) associated with altered syndecan-1 expression43 and for metabolic bone disease.

Supported in part by Florence Carter Fellowship in Leukemia Research from AMA-ERF (to M.V.D.) and Grants No. CA 68494 (to R.D.S.), PO-1 AG 139181 (to E.A.), and CA71145 (to J.K.L.) from the National Institutes of Health. M.V.D. is a recipient of a Clinical Research Career Development Award from the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Address reprint requests to Ralph D. Sanderson, PhD, Department of Pathology, Slot 517, 4301 W Markham, Little Rock, AR 72205; e-mail:SandersonRalphD@exchange.uams.edu.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked "advertisement" is accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

![Fig. 6. Induction of apoptosis of myeloma cells by syndecan-1. Myeloma cell lines ([A] and [B] ARH-77 cells; [C] and [D], arp cells) were incubated with media alone (A and C) or purified syndecan-1 (4 nmol/L) for 48 hours (B and D). Apoptosis was examined using flow cytometry-based TUNEL (TdT-mediated dUTP nick end labeling) assay (Boehringer Mannheim) using the manufacturer's protocol. For negative control (thin line), cells were stained with label solution in the absence of TdT. For test sample (thick line), cells were stained with TUNEL reaction mixture according to manufacturer's protocol. The apoptotic population is marked by an arrow. Figures represent one of three representative experiments.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/91/8/10.1182_blood.v91.8.2679.2679_2679_2688/5/m_blod40853006ax.jpeg?Expires=1769189895&Signature=wL34BdMN5HY~7wI6aujxknCOyS4A83fhWJHaLxVaKc7-dnZhwu6FFjegKG7zZ9A0HHd4Ig0OpRmGV3~vssgnRB40KUG8-~5iUj0bWrSetBtVx0T~vLCjpmtOPDVSMvob2fpCXwxcHCyvN42YudyUb9At5ZpSB-fTS~OWUENnlHxcenSFnlQiGOu7TxIBAKH5L~NRubc6yb49gfMVZTwagGR8wLICMVGYGbOIp9CGgjUv5RJohk8ZRQzj05d9Hei7SdZ92XY0KCJylZyooJYa3fSHk7sAfouAQKL3VlcKvXlJvPMnV03Q2vDqQi0BM0R6ZhUrnqO2a46p90X2j46WVQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 6. Induction of apoptosis of myeloma cells by syndecan-1. Myeloma cell lines ([A] and [B] ARH-77 cells; [C] and [D], arp cells) were incubated with media alone (A and C) or purified syndecan-1 (4 nmol/L) for 48 hours (B and D). Apoptosis was examined using flow cytometry-based TUNEL (TdT-mediated dUTP nick end labeling) assay (Boehringer Mannheim) using the manufacturer's protocol. For negative control (thin line), cells were stained with label solution in the absence of TdT. For test sample (thick line), cells were stained with TUNEL reaction mixture according to manufacturer's protocol. The apoptotic population is marked by an arrow. Figures represent one of three representative experiments.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/91/8/10.1182_blood.v91.8.2679.2679_2679_2688/5/m_blod40853006cx.jpeg?Expires=1769189895&Signature=uug6G0C3RJwFDQdzXpi0sOopFPjxVgj9vVTNGIWp485OzvMX9KH5GjKQBkz0WJxG~Ox-FBD3OjUdJj7mp63m27c39380EV-UExlbvz~nktR5THH2D97W9pEXWcFGTOb4cmk1EmGLqXKfgd2ubCt0Q6Ohkjj3yEpujMQRz6HnT1w0M~aMd5J1nhB2dskFPkb1scRzccIGFETNnSdE72plnmHkVhUsqaTbKc-Q2vVW0zaWQAD7yTvHbtxuSpZj4JyhU4D9GPK-rSdj1ufx-ux11bMBZRCz28SyKpUxozbxhT9CJYMfweGpjt~o9SIg~jlOqEEEfQM~X8grdvfqW-61Ew__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal