Abstract

Although serum concentrations of ascorbic acid seldom exceed 150 μmol/L, mature neutrophils and mononuclear phagocytes accumulate millimolar concentrations of vitamin C. Relatively little is known about the mechanisms regulating this process. The colony-stimulating factors (CSFs), which are central modulators of the production, maturation, and function of human granulocytes and mononuclear phagocytes, are known to stimulate increased glucose uptake in target cells. We show here that vitamin C uptake in neutrophils, monocytes, and a neutrophilic HL-60 cell line is enhanced by the CSFs. Hexose uptake studies and competition analyses showed that dehydroascorbic acid is taken up by these cells through facilitative glucose transporters. Human monocytes were found to have a greater capacity to take up dehydroascorbic acid than neutrophils, related to more facilitative glucose transporters on the monocyte cell membrane. Ascorbic acid was not transported by these myeloid cells, indicating that they do not express a sodium-ascorbate cotransporter. Granulocyte (G)- and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) stimulated increased uptake of vitamin C in human neutrophils, monocytes, and HL-60 neutrophils. In HL-60 neutrophils, GM-CSF increased both the transport of dehydroascorbic acid and the intracellular accumulation of ascorbic acid. The increase in transport was related to a decrease in Km for transport of dehydroascorbic acid without a change in Vmax. Increased ascorbic acid accumulation was a secondary effect of increased transport. Triggering the neutrophils with the peptide fMetLeuPhe led to enhanced vitamin C uptake by increasing the oxidation of ascorbic acid to the transportable moiety dehydroascorbic acid, and this effect was increased by priming the cells with GM-CSF. Thus, the CSFs act at least at two distinct functional loci to increase cellular vitamin C uptake: conversion of ascorbic acid to dehydroascorbic acid by enhanced oxidation in the pericellular milieu and increased transport of DHA through the facilitative glucose transporters at the cell membrane. These results link the regulated uptake of vitamin C in human host defense cells to the action of CSFs.

WIDELY HELD notions connect vitamin C with host defense against microorganisms.1-4 Because humans cannot synthesize vitamin C,5 it must be provided externally and transported intracellularly.6 Vitamin C is present in human blood at concentrations of about 50 μmol/L almost exclusively in the reduced form, ascorbic acid. Similarly, ascorbic acid is present in cells and tissues at concentrations that can exceed by several orders of magnitude the blood levels of the vitamin. These observations led to the proposal that the transport of vitamin C by human cells occurs against a concentration gradient and in a sodium-dependent manner, with the direct participation of sodium-ascorbate cotransporters.6 The reduced form of vitamin C, ascorbic acid, is present in human neutrophils and mononuclear phagocytes in high (millimolar) concentrations, but the identity and functional properties of the mechanisms regulating the uptake and accumulation of vitamin C in these cells are still a matter of controversy.6,7 Studies of the interaction of vitamin C with host defense cells have been confounded by the lack of standard procedures for measuring the uptake of ascorbic acid in cells. In solution, ascorbic acid undergoes reversible oxidation to dehydroascorbic acid, a process that can be catalyzed and greatly accelerated by traces of metal ions and prevented by metal chelators or reducing agents.8-10 The uncontrolled oxidation of vitamin C in solution has resulted in contradictory evidence concerning the mechanism and the chemical form of vitamin C (reduced or oxidized) transported by mammalian cells.6,7,11-20 We recently showed that facilitative hexose transporters are the primary route of cellular vitamin C transport in myeloid cells and provided evidence that they transport only the oxidized form of the vitamin, dehydroascorbic acid.10,21 22 In vitro, human neutrophils and HL-60 cells incubated in the presence of dehydroascorbic acid accumulate high intracellular concentrations of reduced ascorbic acid in a matter of minutes, but no dehydroascorbic acid is detected intracellularly. These cells transport dehydroascorbic acid down a concentration gradient through facilitative hexose transporters. Once inside the cell, the dehydroascorbic acid is reduced to ascorbic acid, a mechanism allowing for the trapping and accumulation of high intracellular concentrations of reduced vitamin C.

Granulocyte (G)- and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) are important regulators of the growth and maturation of myeloid precursor cells and they also enhance the function of mature neutrophils and mononuclear phagocytes.23-29 The myeloid CSFs stimulate increased glucose uptake in target cells, presumably to provide increased metabolic fuel for heightened cellular activity. In the case of GM-CSF, signaling for increased glucose uptake in target cells is mediated through the GM-CSF receptor α subunit.30,31 Because vitamin C is transported into myeloid host defense cells as dehydroascorbic acid through the facilitative glucose transporters, we hypothesized that the myeloid CSFs could be important regulators of vitamin C uptake in target host defense cells. GM-CSF could affect vitamin C uptake in myeloid cells by mechanisms involving a direct effect on the membrane transporters and also increase the oxidative generation of the transported substrate, dehydroascorbic acid, from ascorbic acid. Neutrophils and mononuclear phagocytes activated by the chemotactic peptide fMetLeuPhe undergo the oxidative burst.32 GM-CSF primes the cells for the oxidative response, with the result that myeloid cells exposed to GM-CSF and then stimulated with fMetLeuPhe generate increased amounts of oxidant molecules.33

We show here that G- and GM-CSF increase the cellular uptake of vitamin C by human myeloid host defense cells. Triggering the neutrophils with the chemotactic peptide fMetLeuPhe also led to increased uptake of vitamin C, and this effect was increased by priming the cells with GM-CSF. Our results indicate that the effect of GM-CSF is probably mediated by changes in the functional activity of the glucose transporters that permit the cellular uptake of dehydroascorbic acid by cells. The data also indicate that fMetLeuPhe affects cellular vitamin C uptake by a mechanism that involves the oxidation of ascorbic acid to dehydroascorbic acid without affecting the activity of the transporters. These findings link vitamin C uptake by mature myeloid cells to the action of CSFs, providing evidence that humoral modulators of host defense stimulate increased transport of vitamin C in cells central to host defense against microorganisms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Leukopaks were provided by the New York Blood Center. Neutrophils were purified by Ficoll-Hypaque density centrifugation followed by dextran sedimentation of the erythrocytes. From these preparations, monocytes were selected by adherence to culture dishes and cultured overnight in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (IMDM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 1% glutamine and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. A neutrophilic subline of HL-60 cells34 was cultured in IMDM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and 1% L-glutamine. Cell viability was always greater than 95% as assessed by trypan blue exclusion.

For uptake assays, the cells were suspended in incubation buffer (15 mmol/L Hepes pH 7.6, 135 mmol/L NaCl, 5 mmol/L KCl, 1.8 mmol/L CaCl2, 0.8 mmol/L MgCl2), washed by centrifugation in the same buffer and resuspended at 0.5 to 2 × 107 cells per milliliter. Similarly, adherent cells were washed with incubation buffer twice. Ascorbic acid uptake assays were performed in a final volume of 0.2 mL incubation buffer containing 2 to 15 × 106 cells, 0.1 to 0.4 μCi of L-[14C]-ascorbic acid (specific activity 8.2 mCi/mmol, NEN-Dupont, Wilmington, DE), and a final concentration of 0.05 to 15 mmol/L ascorbic acid. For dehydroascorbic acid uptake, 1 to 10 U of ascorbic acid oxidase (50 U/mg protein, Sigma, Milwaukee, WI) were added to the incubation mixture and incubated for 2 minutes before adding the cells. The oxidation of ascorbic acid was monitored by the decrease in absorbance at 266 nm and also by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (see below).

Uptake was stopped by adding 10 volumes of cold Ca2+ and Mg2+-free phosphate-buffered saline. The cells were washed twice with cold phosphate-buffered saline, lysed in 10 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) containing 0.2% sodium dodecyl sulfate and the incorporated radioactivity was determined by liquid scintillation counting.10,21 For HPLC analysis, cells were lysed in 60% methanol, 1 mmol/L EDTA (pH 8.0) at 4°C, and the supernatants obtained were stored at −70°C until use. For samples containing vitamin C in solution, the samples were adjusted to final concentrations of methanol and EDTA of 60% and 1 mmol/L, respectively, and stored at −70°C. HPLC analysis was performed using a Whatman strong anion exchange reverse phase column (Partisil 10 SAX, 4.6 mm × 25 cm, 10-μm particle) with a silica preconditioning column (Whatman guard cartridge anion exchanger). The HPLC system was equipped with a two-channel ultraviolet (UV) diode detector and a radioactivity detector arranged in series.35The conditions of the chromatography were modified to decrease the total running time to 35 minutes. The elution conditions were: temperature, 25°C; flow, 1 mL/min; buffer A (7 mmol/L KH2PO4, 7 mmol/L KCl, pH 4.0) and buffer B (0.25 mol/L KH2PO4, 0.5 mol/L KCl, pH 5.0); mobile phase, isocratic buffer A from 0 to 5 minutes, linear gradient from 100% buffer A and 0% buffer B to 50% buffer B from 5 to 20 minutes, 100% buffer B from 20 to 25 minutes, and 100% buffer A from 25 to 35 minutes to equilibrate the column. Under these conditions, dehydroascorbic acid eluted at 4.4 minutes and ascorbic acid eluted at 10.4 minutes.

Hexose uptake assays were similarly performed using 1 μCi of 3-O-[methyl-3H]-D-glucose (specific activity 10 Ci/mmol, NEN-Dupont) and 0.3 to 20 mmol/L 3-O-methyl-D-glucose (methylglucose) or 1 μCi of 2-[1,2-3H(N)]-deoxy-D-glucose (specific activity 26.2 Ci/mmol, NEN-Dupont) and 0.3 to 20 mmol/L 2-deoxy-D-glucose (deoxyglucose). When appropriate, competitors and inhibitors were added to the uptake assays or the cells were preincubated in their presence. Cells were treated with recombinant human GM-CSF (a gift from Amgen Inc, Thousand Oaks, CA) as indicated in the figure legends.

RESULTS

Facilitated transport of dehydroascorbic acid in neutrophils and monocytes.

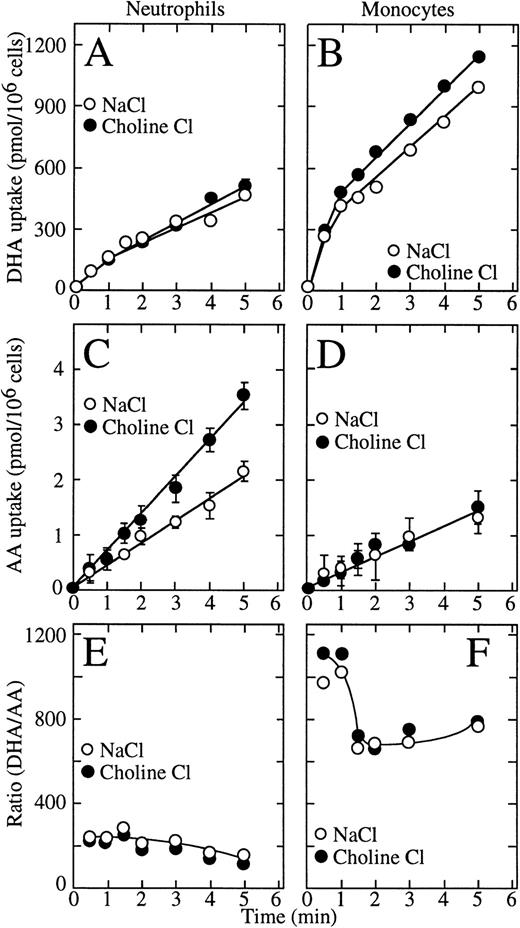

We previously showed that uptake of dehydroascorbic acid by human neutrophils and HL-60 cells is mediated by facilitative glucose transporters and that these cells do not transport ascorbic acid.10,21,22 Data have been presented, however, implying that human neutrophils and HL-60 cells can transport ascorbic acid through a sodium-dependent ascorbate cotransporter.7 In the present studies, we examined the sodium dependence of the transport of vitamin C by human neutrophils and monocytes. Long uptake assays (30 minutes to 2 hours) showed low level cellular uptake of radioactive ascorbic acid, but those conditions are unsuited to study transport of ascorbic acid due to the slow oxidation of ascorbic acid to dehydroascorbic acid in solution.8-10 Given the high efficiency of transport of dehydroascorbic acid by the glucose transporters, the oxidation of even a fraction of a percent of the ascorbic acid present in the incubation medium will result in the rapid transport of the generated dehydroascorbic acid.22Therefore, we used short uptake assays (5 minutes or less) to minimize the effect of oxidation of ascorbic acid, and used 15 million cells per assay to increase the sensitivity of the uptake assay. These studies showed that dehydroascorbic acid was efficiently taken up by human neutrophils and monocytes and that uptake was unchanged in sodium-free medium, indicating that it was sodium independent (Fig 1A and B). The initial rate of dehydroascorbic acid uptake by monocytes (450 pmol/min/106cells) was threefold higher than by neutrophils (150 pmol/min/106 cells). Also, for neutrophils, dehydroascorbic acid uptake increased linearly with time for the length of the uptake assay (Fig 1A), whereas for monocytes, uptake was biphasic, with a rapid initial linear phase of uptake that lasted approximately 1 minute followed by a second slower linear phase with a rate that was constant for the remainder of the uptake assay (Fig 1B).

Transport of dehydroascorbic acid by human neutrophils and monocytes. (A) Uptake of dehydroascorbic acid (DHA) by human neutrophils in the presence of NaCl (○) or choline chloride (•). (B) Uptake of dehydroascorbic acid by human monocytes in the presence of NaCl (○) or choline chloride (•). (C) Uptake of ascorbic acid (AA) by human neutrophils in the presence of NaCl (○) or choline chloride (•). (D) Uptake of ascorbic acid by human monocytes in the presence of NaCl (○) or choline chloride (•). (E) Ratio of the uptake of dehydroascorbic acid versus ascorbic acid by human neutrophils in the presence of NaCl (○) or choline chloride (•). (F) Ratio of the uptake of dehydroascorbic acid versus ascorbic acid by human monocytes in the presence of NaCl (○) or choline chloride (•). Data represent the mean ± SD of four samples and correspond to one of three similar experiments.

Transport of dehydroascorbic acid by human neutrophils and monocytes. (A) Uptake of dehydroascorbic acid (DHA) by human neutrophils in the presence of NaCl (○) or choline chloride (•). (B) Uptake of dehydroascorbic acid by human monocytes in the presence of NaCl (○) or choline chloride (•). (C) Uptake of ascorbic acid (AA) by human neutrophils in the presence of NaCl (○) or choline chloride (•). (D) Uptake of ascorbic acid by human monocytes in the presence of NaCl (○) or choline chloride (•). (E) Ratio of the uptake of dehydroascorbic acid versus ascorbic acid by human neutrophils in the presence of NaCl (○) or choline chloride (•). (F) Ratio of the uptake of dehydroascorbic acid versus ascorbic acid by human monocytes in the presence of NaCl (○) or choline chloride (•). Data represent the mean ± SD of four samples and correspond to one of three similar experiments.

In marked contrast to their ability to take up large amounts of dehydroascorbic acid, human neutrophils and monocytes accumulated only very small amounts of radioactive material when incubated with14C-ascorbic acid (Fig 1C and D). Moreover, uptake under these conditions was independent of the presence of sodium ions in the incubation medium, which militates strongly against the participation of a sodium-dependent ascorbate cotransporter. In fact, neutrophils consistently accumulated more radioactive material when incubated with ascorbic acid in the absence than in the presence of sodium ions (Fig1C). In both cell types, uptake in cells incubated with ascorbic acid was only a small fraction of the uptake observed in cells exposed to dehydroascorbic acid. The initial rate of uptake by neutrophils incubated with ascorbic acid in the presence of sodium ions was 0.42 pmol/min/106 cells compared with 0.30 pmol/min/106 for monocytes and increased to 0.70 nmol/min/106 cells in the absence of sodium. Thus, neutrophils take up 150-fold to 250-fold more vitamin C when incubated with dehydroascorbic acid compared with ascorbic acid, while monocytes take up approximately 700-fold to 1,200-fold more vitamin C when presented with dehydroascorbic acid compared with ascorbic acid (Fig 1E and F).

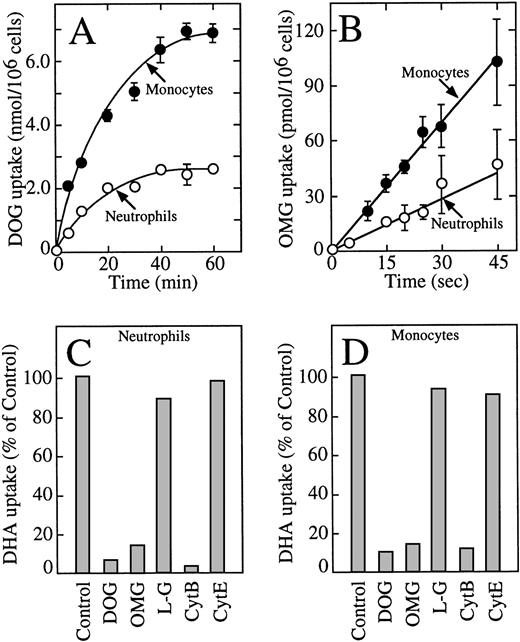

These data indicate that human neutrophils and monocytes transport only the oxidized form of vitamin C, dehydroascorbic acid, and do not express a sodium-dependent cotransporter with the capacity to transport ascorbic acid. The results also indicate that human monocytes have an increased capacity to take up dehydroascorbic acid compared with neutrophils. We hypothesized that the increased cellular uptake of dehydroascorbic acid by human monocytes could reflect an increased number of glucose transporters engaged in the transport of dehydroascorbic acid. Consistent with this hypothesis, monocytes also showed a greater capacity than neutrophils to take up deoxyglucose (Fig 2A), a substrate that is transported only by glucose transporters of the facilitative type.36Uptake of deoxyglucose by monocytes and neutrophils increased in a linear fashion for the first 10 minutes and reached a plateau at about 50 minutes. At the end of the 60-minute uptake assay, monocytes accumulated 2.6-fold more deoxyglucose (presumably as deoxyglucose phosphate) than neutrophils. The difference in uptake was even greater during the initial part of the uptake curve (10 minutes or less), which more closely reflects transport as opposed to accumulation. The initial rate of deoxyglucose uptake by monocytes (400 pmol/min/106cells) was 3.4-fold higher than by neutrophils (117 pmol/min/106 cells) (Fig 2A). A similar increased transport of the nonmetabolized substrate methylglucose was observed in monocytes (2.3-fold) compared with human neutrophils (Fig 2B). The initial rate of methylglucose uptake by monocytes was 140 pmol/min/106cells compared with 59 pmol/min/106 cells for neutrophils. Methylglucose is a nonmetabolized glucose analog, and therefore changes in the cellular uptake of this substrate are not associated with intracellular events that occur after transport.36 In neutrophils and monocytes, the transport of dehydroascorbic acid was specifically completed by the transported substrates deoxyglucose and methylglucose, but not by L-glucose, a hexose incapable of interacting with the glucose transporters (Fig 2C and D). Additionally, transport was inhibited by cytochalasin B, a specific inhibitor of facilitated transport,36-39 but not by the noninhibitory compound cytochalasin E (Fig 2C and D). The substrate of the sodium-dependent glucose cotransporter α-methyl-D-glucopyranoside40 did not affect the uptake of dehydroascorbic acid by the cells, arguing against the participation of this transporter in the transport of dehydroascorbic acid (data not shown). Overall, the data are consistent with the direct participation of facilitative glucose transporters in the transport of dehydroascorbic acid by human neutrophils and monocytes.

Human neutrophils and monocytes take up dehydroascorbic acid through facilitative glucose transporters. (A) Uptake of deoxyglucose (DOG) by human neutrophils (○) and monocytes (•). (B) Transport of methylglucose (OMG) by human neutrophils (○) and monocytes (•). (C) Effect of competitors and inhibitors on the uptake of dehydroascorbic acid by human neutrophils. Uptake was assayed in the absence (control) or in the presence of 30 mmol/L deoxyglucose, methylglucose, or L-glucose (LG), or the cells were incubated with 20 μmol/L cytochalasin B (CytB) or cytochalasin E (CytE) for 5 minutes before the uptake assay. (D) Effect of competitors and inhibitors on the uptake of dehydroascorbic acid by human monocytes. Uptake was assayed in the absence (control) or in the presence of 30 mmol/L deoxyglucose, methylglucose, or L-glucose, or the cells were incubated with 20 μmol/L cytochalasin B or cytochalasin E for 5 minutes before the uptake assay. For (A and B), the data represent the mean ± SD of four samples and correspond to one of three similar experiments. For (C and D), the data represent the average of two experiments performed in duplicate.

Human neutrophils and monocytes take up dehydroascorbic acid through facilitative glucose transporters. (A) Uptake of deoxyglucose (DOG) by human neutrophils (○) and monocytes (•). (B) Transport of methylglucose (OMG) by human neutrophils (○) and monocytes (•). (C) Effect of competitors and inhibitors on the uptake of dehydroascorbic acid by human neutrophils. Uptake was assayed in the absence (control) or in the presence of 30 mmol/L deoxyglucose, methylglucose, or L-glucose (LG), or the cells were incubated with 20 μmol/L cytochalasin B (CytB) or cytochalasin E (CytE) for 5 minutes before the uptake assay. (D) Effect of competitors and inhibitors on the uptake of dehydroascorbic acid by human monocytes. Uptake was assayed in the absence (control) or in the presence of 30 mmol/L deoxyglucose, methylglucose, or L-glucose, or the cells were incubated with 20 μmol/L cytochalasin B or cytochalasin E for 5 minutes before the uptake assay. For (A and B), the data represent the mean ± SD of four samples and correspond to one of three similar experiments. For (C and D), the data represent the average of two experiments performed in duplicate.

Effect of G- and GM-CSF on the capacity of human neutrophils and monocytes to take up dehydroascorbic acid.

Human neutrophils incubated in the presence of 0.5 nmol/L GM-CSF showed an increased ability to take up dehydroascorbic acid (Fig 3A). The effect of GM-CSF on uptake developed rapidly, with half-maximal stimulation of uptake observed at approximately 30 minutes with a maximal effect seen at 60 minutes. G-CSF at 0.5 nmol/L exerted a similar effect on the ability of human neutrophils to take up dehydroascorbic acid (Fig 3A). Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) at 1 nmol/L did not induce a change in the capability of these cells to take up dehydroascorbic acid (Fig 3A). We also tested the effect of the neutrophil triggering peptide fMetLeuPhe.32,33 No effect of 10 μmol/L fMetLeuPhe on the uptake of dehydroascorbic acid by neutrophils was observed in these studies, a concentration known to produce a clear biologic response in these cells. Dose-response experiments showed that GM- and G-CSF exerted their action at low picomolar concentrations (Fig 3B). Half-maximal stimulation of uptake was seen at 3 pmol/L GM-CSF, a result consistent with the expression of high-affinity GM-CSF receptors in these cells.24-28 41-43 Maximal activation was reached at 30 pmol/L GM-CSF, with no further increase in uptake at concentrations of GM-CSF as high as 10 nmol/L. G-CSF also showed a dose-dependent effect enhancing the ability of human neutrophils to take up dehydroascorbic acid, with half-maximal and maximal effects observed at 10 and 100 pmol/L G-CSF (Fig 3B). GM-CSF consistently induced a larger increase in dehydroascorbic acid uptake compared with G-CSF, with increases of 60% above control values. TNF did not cause changes in neutrophil uptake of dehydroascorbic acid at concentrations from 1 pmol/L to 10 nmol/L (Fig 3B), confirming the specificity of the effect of G- and GM-CSF.

GM-CSF and G-CSF increase the uptake of dehydroascorbic acid (DHA) by human neutrophils and monocytes. (A) Time course of the effect of GM-CSF (•) and TNF (□) on the uptake of dehydroascorbic acid by human neutrophils. Cells were treated with 0.5 nmol/L GM-CSF or 1 nmol/L TNF for the time periods indicated in the figure. Uptake of dehydroascorbic acid was measured afterwards in a 5-minute assay. Data represent the mean ± SD of four samples. (B) Dose-dependence of the effect of GM-CSF (•), G-CSF (○) and TNF (□) on the uptake of dehydroascorbic acid by human neutrophils. Cells were incubated for 30 minutes in the presence of the indicated concentrations of the different agonists and uptake of dehydroascorbic acid was measured in a 5-minute assay. (C) Time course of the effect of GM-CSF (•) and G-CSF (○) on the uptake of dehydroascorbic acid by human monocytes. Cells were treated with 0.5 nmol/L GM- or G-CSF, or left untreated (controls, □), for the time periods indicated in the figure. Uptake of dehydroascorbic acid was measured afterwards in a 5-minute assay. Data represent the mean ± SD of four samples. (D) Dose-dependence of the effect of GM-CSF (•) and G-CSF (○) on the uptake of dehydroascorbic acid by human monocytes. Cells were incubated for 30 minutes in the presence of the indicated concentrations of the different agonists and uptake of dehydroascorbic acid was measured in a 5-minute assay. Data represent the mean ± SD of four samples and correspond to one of three similar experiments.

GM-CSF and G-CSF increase the uptake of dehydroascorbic acid (DHA) by human neutrophils and monocytes. (A) Time course of the effect of GM-CSF (•) and TNF (□) on the uptake of dehydroascorbic acid by human neutrophils. Cells were treated with 0.5 nmol/L GM-CSF or 1 nmol/L TNF for the time periods indicated in the figure. Uptake of dehydroascorbic acid was measured afterwards in a 5-minute assay. Data represent the mean ± SD of four samples. (B) Dose-dependence of the effect of GM-CSF (•), G-CSF (○) and TNF (□) on the uptake of dehydroascorbic acid by human neutrophils. Cells were incubated for 30 minutes in the presence of the indicated concentrations of the different agonists and uptake of dehydroascorbic acid was measured in a 5-minute assay. (C) Time course of the effect of GM-CSF (•) and G-CSF (○) on the uptake of dehydroascorbic acid by human monocytes. Cells were treated with 0.5 nmol/L GM- or G-CSF, or left untreated (controls, □), for the time periods indicated in the figure. Uptake of dehydroascorbic acid was measured afterwards in a 5-minute assay. Data represent the mean ± SD of four samples. (D) Dose-dependence of the effect of GM-CSF (•) and G-CSF (○) on the uptake of dehydroascorbic acid by human monocytes. Cells were incubated for 30 minutes in the presence of the indicated concentrations of the different agonists and uptake of dehydroascorbic acid was measured in a 5-minute assay. Data represent the mean ± SD of four samples and correspond to one of three similar experiments.

We next examined the effect of G- and GM-CSF on the transport of dehydroascorbic acid by human monocytes. Human monocytes responded to G- and GM-CSF with a rapid increase in their ability to take up dehydroascorbic acid (Fig 3C). Half-maximal stimulation was observed at 30 minutes, with maximal effect observed after 60 minutes of exposure to the cytokines. The effect of G- and GM-CSF was dose dependent, with half-maximal stimulation observed at 3 pmol/L and maximal activation of uptake observed at 10 pmol/L (Fig 3D).

Effect of GM-CSF on dehydroascorbic acid uptake by HL-60 neutrophils.

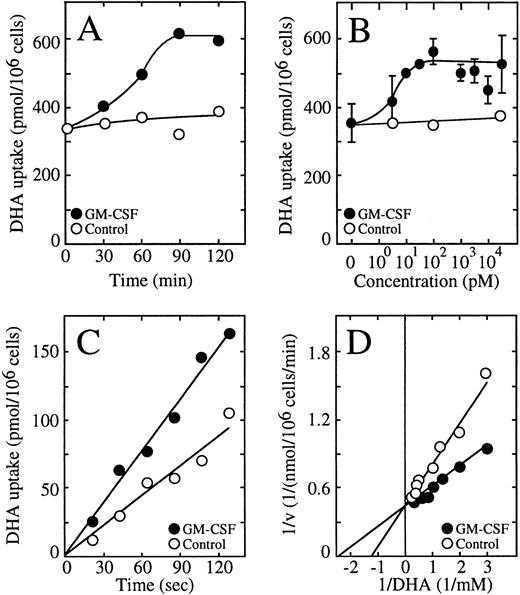

We recently characterized the transport of dehydroascorbic acid by HL-60 cells and showed the direct participation of the facilitative glucose transporter GLUT1 in this process.10 22 We performed a detailed analysis of vitamin C uptake in these cells and established that transport of dehydroascorbic acid is the only mechanism by which the HL-60 cells acquire vitamin C, and that they do not express sodium-dependent ascorbate cotransporters. Thus, the HL-60 cells represent an ideal in vitro model to address the issue of the regulation of vitamin C uptake in myeloid cells. Similar to human neutrophils, a neutrophilic clone of HL-60 cells responded to GM-CSF with an increased uptake of dehydroascorbic acid that was time and dose dependent (Fig 4A and B). Half-maximal activation was observed at 60 minutes, with maximal effect evident after 90 minutes of exposure to 0.5 nmol/L GM-CSF (Fig 4A). GM-CSF induced half-maximal activation of uptake at approximately 10 pmol/L, and maximal activation was observed at 100 pmol/L, with no further activation of uptake seen at concentrations of GM-CSF as high as 10 nmol/L (Fig 4B). The effect of GM-CSF on the uptake of dehydroascorbic acid was most evident during the first 5 minutes of uptake, suggesting that it was related to the transport step rather than to the secondary step leading to the intracellular accumulation of elevated concentrations of ascorbic acid. Consistent with this interpretation, short uptake experiments indicated that the transport of dehydroascorbic acid was increased by treating the HL-60 neutrophils with GM-CSF (Fig 4C). Kinetic analysis using 30-second uptake assays showed that the transport of dehydroascorbic acid was characterized by a single functional component with an apparent Km of 0.72 ± 0.32 mmol/L and a Vmax of 0.5 ± 0.1 nmol/min/106 cells for the transport of dehydroascorbic acid by control HL-60 neutrophils. On the other hand, cells treated with 0.5 nmol/L GM-CSF had an apparent Km of 0.49 mmol/L and a Vmax of 0.48 nmol/min/106 cells (Fig4D). These results support the concept that GM-CSF treatment induces a change in the capacity of the glucose-vitamin C transporters to transport dehydroascorbic acid.

GM-CSF increases the transport of dehydroascorbic acid by HL-60 neutrophils. (A) Time-course of the effect of GM-CSF. Cells were incubated for varied times in the absence (○) or in the presence (•) of 0.5 nmol/L GM-CSF before measuring the uptake of dehydroascorbic acid (DHA). Data represent the average of two experiments with three replicates each. (B) Dose-response of the effect of GM-CSF. Cells were incubated for 30 minutes in the presence of different concentrations of GM-CSF and uptake of dehydroascorbic acid was measured afterwards. Data represent the mean ± SD of four samples and correspond to one of three similar experiments. (C) Effect of GM-CSF on the transport of dehydroascorbic acid. Cells were incubated for 30 minutes in the absence (○) or in the presence (•) of 0.5 nmol/L GM-CSF and transport of dehydroascorbic acid was measured afterwards. Data represent the average of two experiments with three replicates each. (D) Double reciprocal plot of the effect of GM-CSF on the substrate dependence for dehydroascorbic acid transport. Cells were incubated for 30 minutes in the absence (○) or in the presence (•) of 0.5 nmol/L GM-CSF and transport of dehydroascorbic acid was measured for 30 seconds. Data represent the mean of four samples and correspond to one of three similar experiments.

GM-CSF increases the transport of dehydroascorbic acid by HL-60 neutrophils. (A) Time-course of the effect of GM-CSF. Cells were incubated for varied times in the absence (○) or in the presence (•) of 0.5 nmol/L GM-CSF before measuring the uptake of dehydroascorbic acid (DHA). Data represent the average of two experiments with three replicates each. (B) Dose-response of the effect of GM-CSF. Cells were incubated for 30 minutes in the presence of different concentrations of GM-CSF and uptake of dehydroascorbic acid was measured afterwards. Data represent the mean ± SD of four samples and correspond to one of three similar experiments. (C) Effect of GM-CSF on the transport of dehydroascorbic acid. Cells were incubated for 30 minutes in the absence (○) or in the presence (•) of 0.5 nmol/L GM-CSF and transport of dehydroascorbic acid was measured afterwards. Data represent the average of two experiments with three replicates each. (D) Double reciprocal plot of the effect of GM-CSF on the substrate dependence for dehydroascorbic acid transport. Cells were incubated for 30 minutes in the absence (○) or in the presence (•) of 0.5 nmol/L GM-CSF and transport of dehydroascorbic acid was measured for 30 seconds. Data represent the mean of four samples and correspond to one of three similar experiments.

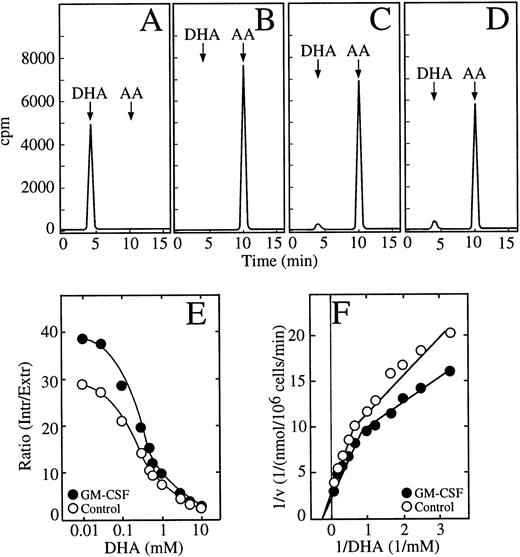

We showed previously that HL-60 promyelocytic cells transport dehydroascorbic acid and accumulate high intracellular concentrations of ascorbic acid.22 In experiments in which the HL-60 neutrophils were incubated with dehydroascorbic acid, we identified the chemical form of vitamin C present in the incubation medium and in cell extracts by HPLC. Analysis of the incubation medium showed that greater than 99% of the radioactivity eluted at 4.4 minutes, the position of dehydroascorbic acid (Fig 5A). When the samples were treated with 1 mmol/L dithiothreitol (DTT) before the HPLC separation, the radioactive peak at 4.4 minutes was no longer visible and the radioactivity eluted at 10.4 minutes, the position of ascorbic acid (Fig 5B). Greater than 95% of the radioactive material taken up by HL-60 neutrophils incubated with dehydroascorbic acid eluted in the position corresponding to ascorbic acid (Fig 5C). A small peak containing approximately 3% of the radioactive material eluted at the expected position of dehydroascorbic acid (Fig 5C). This peak disappeared when the extracts were treated with 1 mmol/L DTT before the HPLC separation, and all the radioactivity eluted in the position of ascorbic acid at 10.4 minutes (data not shown). The ascorbic acid peak disappeared when the cell extracts were treated with ascorbic acid oxidase before the HPLC separation, and a new peak eluting in the position of dehydroascorbic acid was observed (data not shown). The above experiments were performed using 50 μmol/L dehydroascorbic acid, but essentially identical results were obtained, namely greater than 95% of the intracellularly accumulated vitamin C was in the form of ascorbic acid, when the HL-60 cells were incubated with dehydroascorbic acid concentrations as high as 10 mmol/L (Fig 5D). Thus, the HL-60 neutrophils transported dehydroascorbic acid, but accumulated ascorbic acid intracellularly.

GM-CSF increases the accumulation of ascorbic acid by HL-60 neutrophils. (A) HPLC separation of dehydroascorbic acid generated by treating a sample of ascorbic acid with ascorbic acid oxidase. The arrows indicate the elution positions of dehydroascorbic acid (DHA) and ascorbic acid (AA). (B) HPLC separation of a commercial preparation of ascorbic acid after treatment with 1 mmol/L DTT. (C) HPLC separation of a cellular extract from cells incubated with 100 μmol/L dehydroascorbic acid. (D) HPLC separation of a cellular extract from cells incubated with 10 mmol/L dehydroascorbic acid. Data (A through D) represent the result of one of three similar experiments. (E) Accumulation of ascorbic acid. Cells were incubated for 30 minutes in the absence (○) or in the presence (•) of 0.5 nmol/L GM-CSF and afterwards the accumulation of ascorbic acid as a function of different concentrations of dehydroascorbic acid was measured for 10 minutes. Data are expressed as the ratio of the intracellular concentration of ascorbic acid to the extracellular concentration of dehydroascorbic acid. Data represent the mean ± SD of four samples and correspond to one of three similar experiments. (F) Double reciprocal plot of the substrate dependence for ascorbic acid accumulation. Cells were incubated for 30 minutes in the absence (○) or in the presence (•) of 0.5 nmol/L GM-CSF and accumulation of ascorbic acid as a function of different concentrations of dehydroascorbic acid was measured at 10 minutes. Data represent the mean of four samples and correspond to one of three similar experiments.

GM-CSF increases the accumulation of ascorbic acid by HL-60 neutrophils. (A) HPLC separation of dehydroascorbic acid generated by treating a sample of ascorbic acid with ascorbic acid oxidase. The arrows indicate the elution positions of dehydroascorbic acid (DHA) and ascorbic acid (AA). (B) HPLC separation of a commercial preparation of ascorbic acid after treatment with 1 mmol/L DTT. (C) HPLC separation of a cellular extract from cells incubated with 100 μmol/L dehydroascorbic acid. (D) HPLC separation of a cellular extract from cells incubated with 10 mmol/L dehydroascorbic acid. Data (A through D) represent the result of one of three similar experiments. (E) Accumulation of ascorbic acid. Cells were incubated for 30 minutes in the absence (○) or in the presence (•) of 0.5 nmol/L GM-CSF and afterwards the accumulation of ascorbic acid as a function of different concentrations of dehydroascorbic acid was measured for 10 minutes. Data are expressed as the ratio of the intracellular concentration of ascorbic acid to the extracellular concentration of dehydroascorbic acid. Data represent the mean ± SD of four samples and correspond to one of three similar experiments. (F) Double reciprocal plot of the substrate dependence for ascorbic acid accumulation. Cells were incubated for 30 minutes in the absence (○) or in the presence (•) of 0.5 nmol/L GM-CSF and accumulation of ascorbic acid as a function of different concentrations of dehydroascorbic acid was measured at 10 minutes. Data represent the mean of four samples and correspond to one of three similar experiments.

Studies using long uptake assays (30 minutes) showed that GM-CSF treatment induced increased accumulation of ascorbic acid in HL-60 neutrophils incubated with dehydroascorbic acid (Fig 5E). Unstimulated cells accumulated intracellular concentrations of ascorbic acid that greatly exceeded the extracellular concentrations of dehydroascorbic acid to which they were exposed. The ratio of intracellular ascorbic acid to extracellular dehydroascorbic acid reached a maximal value of 29 at 30 μmol/L extracellular dehydroascorbic acid (Fig 5E). Although the ratio decreased as extracellular dehydroascorbic acid increased to 0.1 mmol/L or more, it still maintained a value of 2.2 at 10 mmol/L. GM-CSF–treated cells showed an increased ratio of intracellular ascorbic acid to extracellular dehydroascorbic acid at all dehydroascorbic acid concentrations, reaching a value of 39 at 30 μmol/L dehydroascorbic acid, and 2.6 at 10 mmol/L dehydroascorbic acid. In other words, at 10 mmol/L dehydroascorbic acid, the HL-60 cells accumulated intracellular concentrations of ascorbic acid from 22 to 26 mmol/L. The accumulation data are consistent with the concept that the rate-limiting step of the overall uptake process in long uptake studies is the intracellular reduction of the transported substrate. We performed a kinetic analysis of this step using 30-minute assays. These studies showed the presence of two functional components involved in the intracellular accumulation of ascorbic acid in HL-60 neutrophils incubated with dehydroascorbic acid, as indicated by a break in the slope of the Michaelis and Menten double reciprocal plot (Fig 5F). The low-affinity component, evident at dehydroascorbic acid concentrations of 1 mmol/L or greater, showed a small increase in Vmax, from approximately 0.25 nmol/min/106 cells in untreated cells to 0.31 nmol/min/106 cells in GM-CSF–treated cells, but no change in the apparent Km (3.3 mmol/L) was observed (Fig 5F). On the other hand, the Km of the second kinetic component that was observed at concentrations of dehydroascorbic acid of 1 mmol/L or lower, decreased from 0.68 mmol/L in untreated cells to 0.45 mmol/L in GM-CSF–treated cells.

The above studies established that the HL-60 neutrophils possessed a remarkable capacity to reduce the transported dehydroascorbic acid to ascorbic acid, which is then accumulated intracellularly at high concentrations. The value of 0.68 mmol/L for the high-affinity component was similar to the Km for the transport of dehydroascorbic acid determined in untreated cells using short uptake assays, and the decrease in the high-affinity Km in the GM-CSF–treated cells mirrored the respective decrease observed in the Km for transport in GM-CSF–treated cells. The data are compatible with the concept that GM-CSF regulates accumulation through its direct effect on transport, which is the rate-limiting step for the overall accumulation process at extracellular dehydroascorbic acid concentrations of 1 mmol/L or less. On the other hand, the lack of effect of GM-CSF at high extracellular dehydroascorbic acid levels, at which the reduction of the transported dehydroascorbic acid is the rate-limiting step, suggest that GM-CSF does not directly regulate the reduction-trapping mechanism, and that the increased accumulation of ascorbic acid seen in GM-CSF–treated cells is an effect secondary to increased transport. We further explored this issue by examining the effect of GM-CSF on the cellular uptake of deoxyglucose and methylglucose. A detailed time-course of transport showed that the effect of GM-CSF on the uptake of deoxyglucose was evident during the first 5 minutes of uptake, but no effect was evident at time intervals longer than 20 minutes. Kinetic analyses of the transport of deoxyglucose in cells treated with GM-CSF showed no changes in the maximal velocity for transport (2.3 nmol/min/106 cells) compared with untreated cells (2.2 nmol/min/106 cells) (Fig 6A). GM-CSF treatment, however, induced a change in the transport Km, from 4.5 mmol/L in untreated cells to 2.9 mmol/L in GM-CSF–treated cells (Fig 6A). A similar analysis indicated that the GM-CSF–induced increase in the initial rate of transport of methylglucose was accompanied by a decrease in the Km, from 9 mmol/L in untreated cells to 5.1 mmol/L in GM-CSF–treated cells (Fig 6B). The data are compatible with the concept that, in HL-60 neutrophils, GM-CSF increases the intrinsic functional activity of the facilitative transporters involved in the transport of dehydroascorbic acid.

Effect of GM-CSF on the uptake of deoxyglucose (DOG) and methylglucose (OMG) by HL-60 neutrophils. (A) Double reciprocal plot of the effect of GM-CSF on the substrate dependence for deoxyglucose transport. Cells were incubated for 30 minutes in the absence (○) or in the presence (•) of 0.5 nmol/L GM-CSF and transport of deoxyglucose was measured at 30 seconds. Data represent the mean of four samples. (B) Double reciprocal plot of the effect of GM-CSF on the substrate dependence for methylglucose transport. Cells were incubated for 30 minutes in the absence (○) or in the presence (•) of 0.5 nmol/L GM-CSF and transport of methylglucose was measured at 30 seconds. Data represent the mean of four samples and correspond to one of three similar experiments.

Effect of GM-CSF on the uptake of deoxyglucose (DOG) and methylglucose (OMG) by HL-60 neutrophils. (A) Double reciprocal plot of the effect of GM-CSF on the substrate dependence for deoxyglucose transport. Cells were incubated for 30 minutes in the absence (○) or in the presence (•) of 0.5 nmol/L GM-CSF and transport of deoxyglucose was measured at 30 seconds. Data represent the mean of four samples. (B) Double reciprocal plot of the effect of GM-CSF on the substrate dependence for methylglucose transport. Cells were incubated for 30 minutes in the absence (○) or in the presence (•) of 0.5 nmol/L GM-CSF and transport of methylglucose was measured at 30 seconds. Data represent the mean of four samples and correspond to one of three similar experiments.

Effect of GM-CSF and fMetLeuPhe on dehydroascorbic acid uptake in HL-60 neutrophils.

The uptake experiments described were performed under conditions designed to provide the cells with nonlimiting concentrations of the transported substrate, dehydroascorbic acid. Thus, the CSF-mediated increased ability of the cells to take up dehydroascorbic acid was not related to increased availability of the transported substrate in the extracellular milieu, but rather to a specific effect of the CSF on the uptake of the vitamin. The distinction is important, as a process able to generate dehydroascorbic from ascorbic acid will result in increased uptake of the vitamin by the cells20 because the glucose transporters are specific for dehydroascorbic acid and do not transport reduced ascorbic acid.10,21,22 Neutrophils and mononuclear phagocytes activated by various physiologic signals such as the chemotactic peptide fMetLeuPhe produce molecules that act as strong oxidants, which can generate the transported species, dehydroascorbic acid, from ascorbate.23 32 On the other hand, changes in the number or the intrinsic activity of the glucose transporters involved in the cellular uptake of dehydroascorbic acid at the level of the plasma membrane, will directly affect the transport of dehydroascorbic acid.

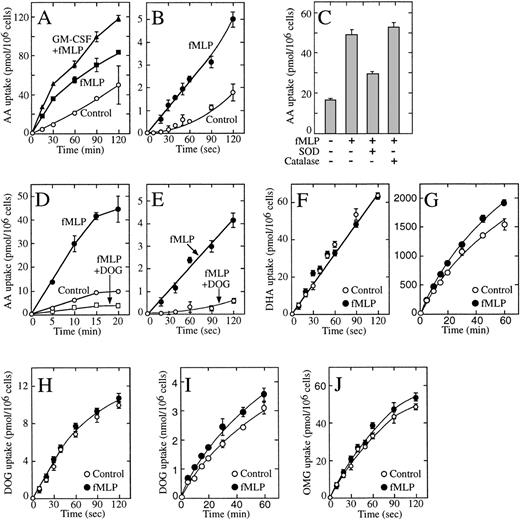

We explored these issues using HL-60 neutrophils.34Unstimulated HL-60 neutrophils produced basal levels of H2O2, and stimulation with fMetLeuPhe activated the oxidative burst that could be measured by an increased production of H2O2 and the highly reactive superoxide anion (data not shown). GM-CSF primed the cells for the oxidative response with the result that cells exposed to GM-CSF and then stimulated with fMetLeuPhe generated even larger amounts of both compounds.33 Because the oxidative burst leads to the oxidation of ascorbic acid to dehydroascorbic acid,20 these results predicted that the generated dehydroascorbic acid would be transported intracellularly and reduced back to ascorbic acid, resulting in the intracellular accumulation of ascorbic acid. There was a substantial accumulation of ascorbic acid in cells activated with fMetLeuPhe under these conditions, and the amount of ascorbic acid accumulated was even greater in cells preincubated with GM-CSF before stimulation with fMetLeuPhe (Fig 7A). Measurable uptake was also observed in untreated cells, an observation consistent with the oxidation of ascorbic acid to dehydroascorbic acid under basal conditions.8-10 In all cases, uptake was only a fraction of that observed in cells directly incubated in the presence of dehydroascorbic acid (Fig 7A and G).

Effect of fMetLeuPhe on the uptake of dehydroascorbic acid (DHA) and ascorbic acid (AA) by HL-60 neutrophils. (A) Effect of GM-CSF and fMetLeuPhe on the uptake of ascorbic acid (AA). Cells were incubated in the absence (○, ▪) or in the presence (▴) of GM-CSF for 30 minutes. Afterwards, uptake of ascorbic acid was assayed in the absence (control, ○) or in the presence (▪, ▴) of 5 μmol/L fMetLeuPhe. (B) Effect of fMetLeuPhe on the initial uptake of ascorbic acid. Uptake of ascorbic acid was assayed in the absence (○) or in the presence (•) of 5 μmol/L fMetLeuPhe. (C) Effect of superoxide dismutase and catalase on the uptake of ascorbic acid uptake. Uptake was measured for 10 minutes in the presence of fMetLeuPhe and superoxide dismutase (SOD) or catalase. (D) Effect of deoxyglucose (DOG) on the uptake of ascorbic acid in cells treated with fMetLeuPhe. Uptake of ascorbic acid was assayed in the absence (○) or in the presence (□, •) of 5 μmol/L fMetLeuPhe and 50 mmol/L deoxyglucose (□). (E) Effect of deoxyglucose on the initial phase of transport of ascorbic acid (AA) by cells treated with fMetLeuPhe. Cells were incubated in medium containing radiolabeled ascorbic acid and 5 μmol/L fMetLeuPhe with (○) or without (•) 50 mmol/L deoxyglucose. (F) Effect of fMetLeuPhe on the transport of dehydroascorbic acid. Transport was assayed in the absence (○) or in the presence (•) of 5 μmol/L fMetLeuPhe. (G) Effect of fMetLeuPhe on the long-term uptake of dehydroascorbic acid. Uptake was assayed in the absence (○) or in the presence (•) of 5 μmol/L fMetLeuPhe. (H) Effect of fMetLeuPhe on transport of deoxyglucose. Transport was assayed in the absence (○) or in the presence (•) of 5 μmol/L fMetLeuPhe. (I) Effect of fMetLeuPhe on the long-term uptake of deoxyglucose. Uptake was assayed in the absence (○) or in the presence (•) of 5 μmol/L fMetLeuPhe. (I) Effect of fMetLeuPhe on the transport of methylglucose (OMG). Transport was assayed in the absence (○) or in the presence (•) of 5 μmol/L fMetLeuPhe. Data represent the mean ± SD of four samples and correspond to one of two to four similar experiments.

Effect of fMetLeuPhe on the uptake of dehydroascorbic acid (DHA) and ascorbic acid (AA) by HL-60 neutrophils. (A) Effect of GM-CSF and fMetLeuPhe on the uptake of ascorbic acid (AA). Cells were incubated in the absence (○, ▪) or in the presence (▴) of GM-CSF for 30 minutes. Afterwards, uptake of ascorbic acid was assayed in the absence (control, ○) or in the presence (▪, ▴) of 5 μmol/L fMetLeuPhe. (B) Effect of fMetLeuPhe on the initial uptake of ascorbic acid. Uptake of ascorbic acid was assayed in the absence (○) or in the presence (•) of 5 μmol/L fMetLeuPhe. (C) Effect of superoxide dismutase and catalase on the uptake of ascorbic acid uptake. Uptake was measured for 10 minutes in the presence of fMetLeuPhe and superoxide dismutase (SOD) or catalase. (D) Effect of deoxyglucose (DOG) on the uptake of ascorbic acid in cells treated with fMetLeuPhe. Uptake of ascorbic acid was assayed in the absence (○) or in the presence (□, •) of 5 μmol/L fMetLeuPhe and 50 mmol/L deoxyglucose (□). (E) Effect of deoxyglucose on the initial phase of transport of ascorbic acid (AA) by cells treated with fMetLeuPhe. Cells were incubated in medium containing radiolabeled ascorbic acid and 5 μmol/L fMetLeuPhe with (○) or without (•) 50 mmol/L deoxyglucose. (F) Effect of fMetLeuPhe on the transport of dehydroascorbic acid. Transport was assayed in the absence (○) or in the presence (•) of 5 μmol/L fMetLeuPhe. (G) Effect of fMetLeuPhe on the long-term uptake of dehydroascorbic acid. Uptake was assayed in the absence (○) or in the presence (•) of 5 μmol/L fMetLeuPhe. (H) Effect of fMetLeuPhe on transport of deoxyglucose. Transport was assayed in the absence (○) or in the presence (•) of 5 μmol/L fMetLeuPhe. (I) Effect of fMetLeuPhe on the long-term uptake of deoxyglucose. Uptake was assayed in the absence (○) or in the presence (•) of 5 μmol/L fMetLeuPhe. (I) Effect of fMetLeuPhe on the transport of methylglucose (OMG). Transport was assayed in the absence (○) or in the presence (•) of 5 μmol/L fMetLeuPhe. Data represent the mean ± SD of four samples and correspond to one of two to four similar experiments.

Short uptake studies in cells incubated with reduced ascorbic acid showed the existence of a short lag period before transport was detected, and transport increased with time in an exponential fashion (Fig 7B). Transport under these conditions, however, was less than 3% of transport observed in cells incubated with dehydroascorbic acid (Fig7B and F). We interpreted these results as indicating the time-dependent generation of small quantities of the transported substrate, dehydroascorbic acid, in the samples containing ascorbic acid. The presence of fMetLeuPhe increased the initial rate of transport by twofold to threefold, although the rate of transport was still a small fraction of that observed in cells incubated with dehydroascorbic acid (Fig 7B and F). The data suggest that the increased rate of transport observed after treating the HL-60 neutrophils with fMetLeuPhe is due to the generation of the transported substrate dehydroascorbic acid from ascorbic acid and not to an effect on the glucose transporters. Consistent with this notion, the presence of the enzyme superoxide dismutase during the activation-uptake assay markedly decreased the effect of fMetLeuPhe on the cellular uptake of ascorbic acid, suggesting the direct involvement of the reactive superoxide anion in this process (Fig 7C). Uptake decreased from 4.7 pmol/min/106 cells in fMetLeuPhe-treated cells to 3.2 pmol/min/106 cells in cells treated with fMetLeuPhe in the presence of superoxide dismutase. No effect of the enzyme catalase was observed in these studies (uptake was 5.5 pmol/min/106cells), a finding that suggests that the generated H2O2 did not induce the oxidation of ascorbic acid (Fig 7C).

An alternative explanation could be that fMetLeuPhe induces the rapid activation of a still unidentified transport system not related to the glucose transporters and capable of transporting ascorbic acid. If that were the case, however, the putative transporter would not be expected to be sensitive to competition by substrates that enter the cell through the glucose transporters. We observed that deoxyglucose completely blocked the increased transport observed in cells incubated with ascorbic acid in the presence of fMetLeuPhe (Fig 7D). The inhibitory effect of deoxyglucose was evident during the first seconds of uptake, confirming the direct participation of the glucose transporters in the uptake of the dehydroascorbic acid generated by the fMetLeuPhe treatment (Fig 7E). We further analyzed this issue by studying the effect of fMetLeuPhe on the ability of the HL-60 neutrophils to transport dehydroascorbic acid. Short uptake studies indicated that fMetLeuPhe exerted no effect on the ability of the HL-60 neutrophils to transport dehydroascorbic acid (Fig 7F), a result consistent with the concept that fMetLeuPhe does not affect the ability of the glucose transporters to transport dehydroascorbic acid. Kinetic analysis indicated that fMetLeuPhe had no affect on the apparent Km and Vmax for the transport of dehydroascorbic acid by the HL-60 neutrophils. The Km and the Vmax for dehydroascorbic acid transport were 0.72 mmol/L and 0.50 nmol/min/106 cells for untreated HL-60 neutrophils, and 0.69 mmol/L and 0.52 nmol/min/106cells for activated HL-60 neutrophils. Longer uptake assays, up to 60 minutes, showed that fMetLeuPhe did not affect the accumulation of vitamin C in HL-60 neutrophils incubated with dehydroascorbic acid (data not shown). Moreover, HL-60 neutrophils incubated for up to 60 minutes in the presence of 1 μmol/L fMetLeuPhe showed no changes in their ability to accumulate ascorbate compared with untreated control cells (Fig 7G).

We next examined the effect of fMetLeuPhe on the cellular uptake of deoxyglucose and methylglucose by the HL-60 neutrophils. These studies showed that fMetLeuPhe did not affect the initial rate or the Km of transport of deoxyglucose by HL-60 neutrophils (Fig 7H). The Km and the Vmax for deoxyglucose transport were 4.8 mmol/L and 1.9 nmol/min/106 cells for untreated HL-60 neutrophils, and 4.7 mmol/L and 2.1 nmol/min/106 cells for activated HL-60 neutrophils. Longer uptake studies showed that fMetLeuPhe had a small, but consistent, stimulatory effect on the cellular trapping of deoxyglucose (Fig 7I), an observation consistent with fMetLeuPhe exerting its effect at a step downstream of the transport of deoxyglucose and therefore not directly related to the glucose transporters. In further studies, we showed that fMetLeuPhe did not affect the initial rate or the Km for the transport of methylglucose by HL-60 neutrophils (Fig 7J). The Km and the Vmax for methylglucose transport were 6.7 mmol/L and 2.4 nmol/min/106 cells for untreated HL-60 neutrophils, and 7.0 mmol/L and 2.6 nmol/min/106 cells for activated HL-60 neutrophils. Overall, the data are consistent with the concept that fMetLeuPhe increases cellular ascorbic acid accumulation in HL-60 neutrophils by inducing the generation of the transported substrate dehydroascorbic acid and does not directly affect the cellular trapping of ascorbic acid or the activity of the glucose transporters.

DISCUSSION

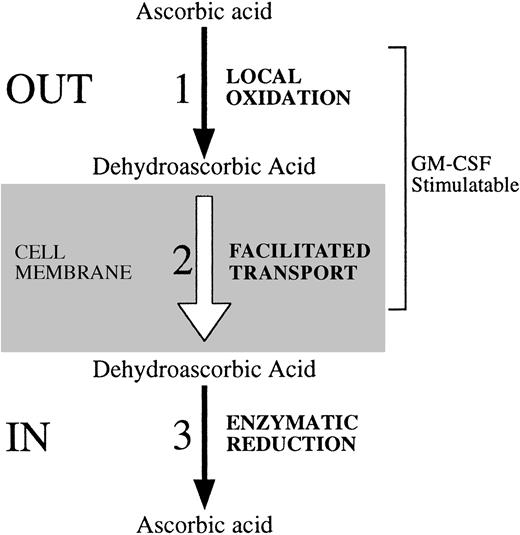

We found that G- and GM-CSF increase the uptake of dehydroascorbic acid in normal human neutrophils, monocytes, and HL-60 neutrophils. Although the molecular details of the regulation are still undefined, the data indicate that under conditions of a nonlimiting supply of dehydroascorbic acid, the cellular uptake of vitamin C can be regulated at the transport step (Fig 8). The increased transport of dehydroascorbic acid in cells treated with GM-CSF is related to the participation of hexose transporters of the facilitative type in the transport of dehydroascorbic acid by normal human neutrophils, monocytes, and HL-60 neutrophils. Growth factors increase the ability of cells to take up hexoses through the glucose transporters by mechanisms involving the recruitment of new transporters to the cell surface and increased intrinsic activity of the transporters.44-46 The human GM-CSF receptor is composed of two subunits, α and β, that together form a high-affinity receptor. Although the β subunit alone is unable to bind GM-CSF, the isolated α subunit binds GM-CSF with low affinity and is referred to as the low-affinity GM-CSF receptor. We recently showed that in human neutrophils and HL-60 cells expressing high-affinity GM-CSF receptors, GM-CSF induces an increased uptake of hexoses in a phosphorylation-independent manner.30 Moreover, glucose uptake experiments in Xenopus laevis oocytes expressing the isolated α subunit of the human GM-CSF receptor, and expressing a low-affinity GM-CSF receptor, indicated that signaling for increased transport is mediated through the isolated α subunit and does not require the presence of the β subunit.30 Also, glucose uptake was activated by GM-CSF in melanoma cell lines that express an isolated α subunit of the GM-CSF receptor.31 Given that the cellular accumulation and trapping of deoxyglucose and ascorbate are not related (phosphorylation v reduction), these observations are consistent with the concept that GM-CSF may signal for increased uptake by regulating the transport process at the level of the glucose transporters. Direct support for this hypothesis was obtained here in experiments showing that GM-CSF induced a decrease in the Km for the transport of dehydroascorbic acid, deoxyglucose, and methylglucose in HL-60 neutrophils, without changes in the Vmax of transport. The most simple explanation consistent with these results is that GM-CSF affects the functional activity of the glucose transporters that mediate the cellular transport of dehydroascorbic acid in these cells. A similar effect, namely a reduction in the transport Km, was described for the effect of IL-3 on glucose transport in the murine cell line 32D.47 Based on the inhibitory effect on transport of protein tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as genistein, the investigators proposed that altered phosphorylation of plasma membrane proteins associated with the glucose transporters may regulate the affinity of the transporter for glucose.47 We have shown, however, that genistein directly inhibits the activity of the glucose transporter in a manner unrelated to its capacity to inhibit tyrosine kinase function.48

Regulatory steps involved in the cellular uptake of vitamin C. We identified three possible regulatory sites at which HL-60 neutrophils regulate their uptake and content of vitamin C. These steps are also likely active in cells such as human neutrophils and monocytes that transport dehydroascorbic acid, but lack the capacity to transport ascorbic acid. (1) The first regulatory site relates directly to the availability of the substrate that is transported. Activation of HL-60 neutrophils with the chemotactic peptide fMetLeuPhe triggers the respiratory burst, with the subsequent generation of reactive oxygen species that can oxidize locally available ascorbic acid to dehydroascorbic acid. As a result, the locally generated dehydroascorbic acid will be rapidly transported intracellularly. (2) The second point of regulation is related to the transport step, and its regulatory potential is determined by changes in the number, molecular identity, or functional status of the transporters of vitamin C. GM-CSF treatment increases the affinity of GLUT1 for the transport of dehydroascorbic acid. As a result, increased transport of dehydroascorbic acid is observed. Growth factors and cytokines that affect the level of expression, subcellular localization, or the intrinsic functional activity of the glucose transporters can potentially modulate the cellular transport of dehydroascorbic acid. (3) A third potential regulatory step is defined by the existence of intracellular mechanisms that determine the capacity of cells to accumulate characteristic intracellular levels of vitamin C. At least two general enzymatic systems with dehydroascorbic acid reductase activity, one GSH dependent and one GSH independent, exist in mammalian cells. No data regarding their regulatory potential are currently available.

Regulatory steps involved in the cellular uptake of vitamin C. We identified three possible regulatory sites at which HL-60 neutrophils regulate their uptake and content of vitamin C. These steps are also likely active in cells such as human neutrophils and monocytes that transport dehydroascorbic acid, but lack the capacity to transport ascorbic acid. (1) The first regulatory site relates directly to the availability of the substrate that is transported. Activation of HL-60 neutrophils with the chemotactic peptide fMetLeuPhe triggers the respiratory burst, with the subsequent generation of reactive oxygen species that can oxidize locally available ascorbic acid to dehydroascorbic acid. As a result, the locally generated dehydroascorbic acid will be rapidly transported intracellularly. (2) The second point of regulation is related to the transport step, and its regulatory potential is determined by changes in the number, molecular identity, or functional status of the transporters of vitamin C. GM-CSF treatment increases the affinity of GLUT1 for the transport of dehydroascorbic acid. As a result, increased transport of dehydroascorbic acid is observed. Growth factors and cytokines that affect the level of expression, subcellular localization, or the intrinsic functional activity of the glucose transporters can potentially modulate the cellular transport of dehydroascorbic acid. (3) A third potential regulatory step is defined by the existence of intracellular mechanisms that determine the capacity of cells to accumulate characteristic intracellular levels of vitamin C. At least two general enzymatic systems with dehydroascorbic acid reductase activity, one GSH dependent and one GSH independent, exist in mammalian cells. No data regarding their regulatory potential are currently available.

We have also identified a second site of functional regulation involved in the uptake of vitamin C by human host defense cells (Fig 8). The second site involves enhanced generation of the transportable moiety of vitamin C, dehydroascorbic acid, in the pericellular milieu. We have shown that neutrophils and monocytes transport only the oxidized form of vitamin C, dehydroascorbic acid, and are incapable of directly transporting ascorbic acid. Detailed analysis showed no evidence of a sodium-dependent ascorbate cotransporter. These considerations lead to the conclusion that the generation of dehydroascorbic acid outside of the cell is essential to the cell's ability to accumulate vitamin C. The human neutrophil has potent oxidative properties and these are greatly enhanced by triggering of the oxidative burst. GM-CSF primes neutrophils for an oxidative response to fMetLeuPhe due to its ability to modulate the fMetLeuPhe receptor.33 We show here that treatment of cells with fMetLeuPhe leads to increased accumulation of vitamin C and that this accumulation is due to the transport of dehydroascorbic acid through the facilitative glucose transporters. Support for this conclusion comes from experiments in which the effect of fMetLeuPhe was markedly decreased in the presence of the enzyme superoxide dismutase, which specifically destroys the superoxide anion by catalyzing its conversion to oxygen and hydrogen peroxide. This interpretation is consistent with the results of blocking experiments in which glucose blocked the effect of fMetLeuPhe by competing with dehydroascorbic acid for the glucose transporter. Further substantiation for this mechanism was provided by showing that fMetLeuPhe did not directly affect the glucose transporter, as there were no changes in the transport of dehydroascorbic acid, deoxyglucose, or methylglucose. Overall, the data indicate that the increased uptake observed in cells treated with fMetLeuPhe and exposed to ascorbic acid was due to the generation of the transported moiety, dehydroascorbic acid, which is then rapidly transported intracellularly through the facilitative glucose transporters and trapped inside the cell by reduction. GM-CSF increased fMetLeuPhe-mediated uptake of vitamin C by increasing the oxidative burst through its priming effect.

The implication of these results is that host defense cells such as neutrophils will take up dehydroascorbic acid generated in situ and recycle it back to ascorbic acid. Dehydroascorbic acid generated by neutrophil oxidative potential can be transported intracellularly by any cell present in the immediate area because glucose transporters are universally present on all cells and tissues. Thus, activated neutrophils participating in inflammatory reactions may provide other cell types with increased antioxidant protection by making the transportable moiety of vitamin C more available. Thus, there appears to be a certain balance between oxidative and antioxidative actions in inflammatory reactions with extracellular oxidation itself permitting increased intracellular concentrations of ascorbic acid.

A third potential site of regulation of vitamin C uptake in host defense cells is at the level of reduction of dehydroascorbic acid to ascorbic acid intracellularly. Our evidence for an effect of GM-CSF on this step is tenuous, although we did find enhanced kinetics of the reduction process. The precise mechanism whereby dehydroascorbic acid is reduced intracellularly is unknown.35 Although accumulation kinetics provide only a crude approach to measuring this function, the data are consistent with the concept that the HL-60 neutrophils possess a remarkable capacity to reduce the recently transported dehydroascorbic acid, which is then trapped as ascorbic acid. Overall, the data suggest that transport of dehydroascorbic acid through facilitative glucose transporters, followed by the intracellular trapping of ascorbic acid, is the only mechanism by which the host defense cells acquire vitamin C.

Vitamin C is fundamental to human physiology and, because humans cannot synthesize it, it must be provided externally and transported intracellularly.1-6 The cellular mechanisms that define the normal or pharmacologic requirements for vitamin C are mostly unknown. Studies with experimental scurvy have shown a critical role for vitamin C in the maintenance of a normally functioning host defense system,1 suggesting that a tight regulation of the cellular content of vitamin C is central for normal host defense. This concept is consistent with our observations that the cellular content of vitamin C in host defense cells can be modulated by cytokines that are key modulators of the production, maturation, and function of these cells. These results establish a role for the CSFs in the regulation of the uptake of vitamin C in host defense cells and thereby implicate positive cellular vitamin C flux to enhanced host defense.

Supported by Grants No. CA30388, HL42107, and CA08748 from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, the Schultz Foundation, the DeWitt Wallace Clinical Research Foundation, and Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center Institutional funds.

Address reprint requests to Juan Carlos Vera, PhD, Program in Molecular Pharmacology and Therapeutics, Box 451, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, 1275 York Ave, New York, NY 10021.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked "advertisement" is accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal