HYDROPS FETALIS is a serious disorder, usually indicative of an ominous prognosis for the affected fetus. There are many causes, including both hereditary and acquired diseases.1-3 In southeast Asia, α-thalassemia is the most common cause of fetal hydrops, accounting for 60% to 90% of the cases.4-7 With population migrations during the past decades, this syndrome is now seen in increasing numbers in other parts of the world.

α-Thalassemia is caused by mutations of the α-globin genes, leading to decreased or absent α-globin chain production from the affected genes. α-Globin chains are the subunits for both fetal hemoglobin (α2γ2) and adult hemoglobin (α2β2). Therefore, severe α-thalassemias can cause anemia in fetuses and in adults. Together with β-thalassemias which are caused by mutations of the β-globin genes, the thalassemias are among the most common single gene mutations in humans.8 They are found mostly in areas where malaria was and may still be endemic.

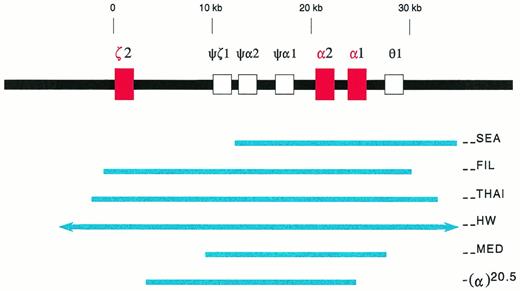

Each person normally has a total of four α-globin genes, two of which are encoded in tandem (in cis) on each chromosome 16 (Fig1). There are α-thalassemia deletions that remove either one or two α-globin genes on each chromosome 16.9-11 11a If both parents are carriers of a deletion removing two α-globin genes in cis on one chromosome 16, there is a one in four risk that in each pregnancy, the fetus might inherit both parental deletional mutations, and lack all α-globin genes.

Deletions in the α-globin gene cluster. The α-globin gene cluster is located on the short arm of chromosome 16 near the telomere. The three active globin genes, ζ2, α2, and α1, are represented by red boxes, whereas the four pseudogenes are represented by open boxes. The extent of the deletions are shown by the solid blue lines. The (--HW) deletion encompasses more than 300 kb, and is represented with arrows in the figure.26 The −(α)20.5 deletion spares the ζ2 gene, and removes the α2 gene and the 5′ region of the α1 gene.29

Deletions in the α-globin gene cluster. The α-globin gene cluster is located on the short arm of chromosome 16 near the telomere. The three active globin genes, ζ2, α2, and α1, are represented by red boxes, whereas the four pseudogenes are represented by open boxes. The extent of the deletions are shown by the solid blue lines. The (--HW) deletion encompasses more than 300 kb, and is represented with arrows in the figure.26 The −(α)20.5 deletion spares the ζ2 gene, and removes the α2 gene and the 5′ region of the α1 gene.29

Because α-globin chains normally are produced throughout gestation, fetuses without α-globin genes would suffer from severe anemia, and thus hypoxia, heart failure, and hydrops fetalis. They would usually survive in utero until the third trimester of gestation when they would succumb to their genetic defects. In contrast to a normal fetus whose major hemoglobin is Hb F (α2γ2), these fetuses have primarily Hb Bart's (γ4). This disorder, first described in 1960, is known as homozygous α-thalassemia or Hb Bart's hydrops fetalis syndrome.12 13

MOLECULAR AND POPULATION GENETICS

The (--SEA) Deletion in Southeast Asia

The α-globin gene cluster is made up of one embryonic ζ-globin gene (ζ2), two α-globin genes (α2 and α1), and four pseudogenes. It spans 30 kb and is located on the short arm of chromosome 16 near the telomere (Fig 1). A major regulatory region, HS-40, is found 40 kb upstream to the ζ-globin gene and is indispensable for the expression of α-globin genes in cis.14,15

In southeast Asia, a common α-thalassemia mutation is the (--SEA) deletion. It is 20.5 kb in length, deleting both α-globin genes, but sparing the embryonic ζ-globin gene (Fig1).9-11 Homozygosity for this deletion, (--SEA/--SEA), is the most common cause of the Hb Bart's hydrops fetalis syndrome. The molecular basis of this genetic disorder was deciphered in 1974, the first ever for human diseases.16 17

The carrier rates of the (--SEA) deletion in southeast Asia are high (Table 1), and there are considerable variations in different regions.7,18-22 However, detailed surveys are lacking. Among people of southeast Asian origin living in the United States, 5.4% of them were found to be carriers of the (--SEA) deletion, whereas 1% were found to be carriers of the (--FIL) deletion (see the following section).23 24

Prevalence of (--SEA) α-Thalassemia Deletion in Southeast Asia

| Regions . | Proportions of Population who are Heterozygous Carriers (%) . | References . |

|---|---|---|

| Hong Kong | 4.5 | 18 |

| Northern Taiwan | 3.5 | 7, 19 |

| Southern China | 5.0-8.8 | 20 |

| Northern Thailand | 14.0 | 21 |

| Central Thailand | 3.7 | 22 |

| Regions . | Proportions of Population who are Heterozygous Carriers (%) . | References . |

|---|---|---|

| Hong Kong | 4.5 | 18 |

| Northern Taiwan | 3.5 | 7, 19 |

| Southern China | 5.0-8.8 | 20 |

| Northern Thailand | 14.0 | 21 |

| Central Thailand | 3.7 | 22 |

Large Deletions Which in Combination With (--SEA) Can Cause Hydrops Fetalis

In southeast Asia, there are three known, large α-thalassemia deletions which remove all the ζ- and α-globin genes in cis, ie, the (--FIL) deletion in the Philippines, the (--THAI) deletion in Thailand, and the (--HW) deletion measuring over 300 kb found in a Chinese family (Fig1).25,26 Diagnostic strategies designed for the (--SEA) deletion would not recognize these large deletions. For Southern analysis, probes which are distal to the deletion breakpoints, such as the LO, 3′αHVR (hypervariable region), and 5′αHVR, have to be used.24-26 Family studies often are helpful.26 Recently, PCR methods with primers designed to detect either the (--FIL) or the (--THAI) deletions have been developed.26a 26b

In a survey of 1,500 people of Filipino ancestry living in Hawaii, the carrier rate of the two α-globin gene deletion is 10%, and approximately 66% of these are of the (--FIL) deletion.27 On the other hand, these large deletions are uncommon in Hong Kong and Taiwan, accounting for less than 3% of those who are carriers of the two α-globin gene deletion.7 18

It is generally accepted that fetuses homozygous for these large deletions do not present with the Hb Bart's hydrops fetalis syndrome because of their demise early in gestation (see the following section on Pathophysiology).25 However, fetuses who are compound heterozygous for the (--SEA) deletion and one of these large deletions, such as (--SEA/--FIL), develop the Hb Bart's hydrops fetalis syndrome.25 26

Deletions Causing Hydrops Fetalis in the Mediterranean Region

Hb Bart's hydrops fetalis has been reported in Cyprus,28,29 Greece,30-33Sardinia,34 and Turkey.35 It is caused by either of two deletional mutations, (--MED) and −(α)20.5.29,32 These deletions are similar to the (--SEA) deletion in that they remove or disrupt both α-globin genes, but not the ζ-globin gene (Fig 1). Because they are quite rare, Hb Bart's hydrops fetalis syndrome is not common in the Mediterranean populations.36 In some cases, consanguinous marriages are involved.34

Other α-thalassemia Mutations

There are many other deletions which remove either two α-globin genes in cis, the entire ζ-α-globin cluster which is sometimes designated as (--Tot), or the HS-40 sequences, thus leading to the silencing of the α-globin gene expression.9-11 11a They have been described in almost every population, and might contribute to causing the hydrops fetalis syndrome. However, no such cases have been recorded, mainly because these deletions are rare.

Deletions which remove only one single α-globin gene on chomosome 16 are common.9-11 A person who is homozygous for these deletions would have a hematologic profile similar to one who is a carrier of the (--SEA) deletion because functionally both individuals possess two α-globin genes. However, those who are either heterozygous or homozygous carriers of the single α-globin gene deletions are not at risk for conceiving fetuses who will lack all α-globin genes. For example, even though single α-globin gene deletions are frequently found in people of African ancestry and in the Indian subcontinent, Hb Bart's hydrops fetalis has not been reported in these populations.37

Unusual α-thalassemia Mutations Causing Hydrops Fetalis

There are rare reports in the literature describing fetuses with the Hb Bart's hydrops fetalis syndrome who also had one apparently normal α-globin gene.7,38-41 Recently, the genotypes of two such fetuses were described, one with (--Tot/αdeletion of GAG in codon 30α) and the other one with (--SEA/αcodon 59 GGC → GAC or Gly→Aspα).41

A person with a single normal α-globin gene, as a result of either the deletion of three α-globin genes, or a combination of two α-globin gene deletion and a point mutation of the third α-globin gene, ordinarily has the so-called Hb H disease. This person has moderate anemia in adult life but usually without need for transfusion, and no hydropic changes during fetal development.9-11 The mechanisms and pathophysiology to account for the severe anemia and hydropic changes of the two aforementioned fetuses remain to be clarified.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY AND CLINICAL FINDINGS

Hemoglobins in Normal and Hydropic Fetuses

During embryogenesis, there are three embryonic hemoglobins, Hb Gower 1 (ζ2ε2), Hb Gower 2 (α2ε2), and Hb Portland 1 (ζ2γ2). By 6 to 7 weeks postconception, the production of embryonic ζ- and ε-globin chains becomes almost undetectable.42 Thereafter, the major hemoglobin in the fetus is Hb F (α2γ2), and later supplemented by less than 10% of Hb A (α2β2) until birth.43 44

In an embryo with a genotype of (--FIL/--FIL), lacking the entire ζ-α-globin gene clusters, the hemoglobins present would be homotetrameric ε4 and Hb Bart's (γ4). These hemoglobins do not undergo heme-heme interaction and Bohr effect, and have very high oxygen affinity.45 They are incapable of oxygen delivery to tissues in the rapidly growing embryo. Therefore, it is generally accepted that the affected embryo would succumb to severe hypoxia very early in gestation, and miscarriage should ensue, thus precluding the detection of these conceptions.25

Fetuses with a genotype of (--SEA/--SEA) usually survive into the third trimester of gestation.9-11This is generally attributed to the fact that the embryonic ζ-globin genes continue to be operative in these fetuses, leading to the formation of about 10% to 20% embryonic Hb Portland 1 (ζ2γ2), and to a much lesser extent, Hb Portland 2 (ζ2β2).46-49 Hb Portland 1 possesses physiological oxygen dissociation capability and can deliver oxygen to fetal tissues.50 Nevertheless, the amounts of these hemoglobins are insufficient to keep pace with the remarkable growth and development of the fetus, especially during the third trimester of gestation. Ultimately the fetus would succumb to hypoxia and heart failure either in utero or shortly after birth.9-11

Fetal Abnormalities

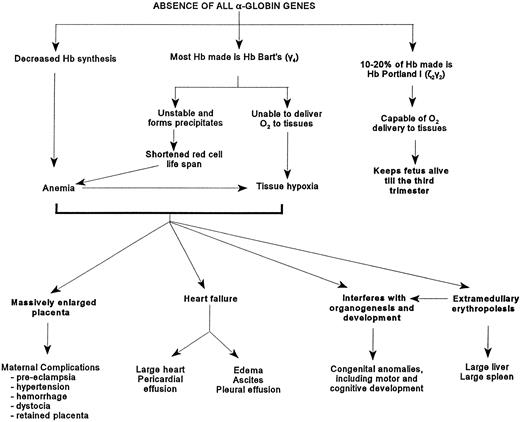

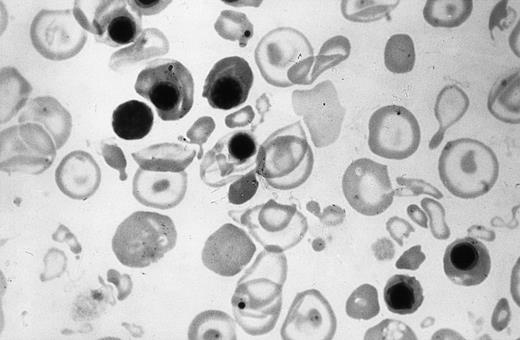

The affected fetuses have decreased hemoglobin synthesis because of the absence of α-globin genes (Fig 2). Most of the hemoglobin present is Hb Bart's (γ4) which is unable to deliver oxygen to tissues, is relatively unstable, and can precipitate and cause shortened red cell survival and possibly ineffective erythropoiesis.45,51 These fetuses are usually severely anemic, although in some, the hemoglobin level can be as high as 100 g/L.10 The circulating erythrocytes are markedly hypochromic and anisopoikilocytic (Fig 3).There are many nucleated erythroblasts in the peripheral blood, indicative of erythropoietic stress. Extensive extramedullary erythropoiesis is found in many organs and sites. This is the cause for the massive hepatomegaly. The spleen can also be enlarged.

Figure depicting the pathophysiology caused by the absence of the α-globin genes.

Figure depicting the pathophysiology caused by the absence of the α-globin genes.

Peripheral blood smear of the newborn shown in Fig 4. Note the hypochromia, anisopoikilocytic changes, and erythroblastosis.

Peripheral blood smear of the newborn shown in Fig 4. Note the hypochromia, anisopoikilocytic changes, and erythroblastosis.

The change from ζ- to α-globin synthesis in a fetus normally is completed by the sixth to seventh week postconception.42Thereafter, in fetuses lacking α-globin genes, severe anemia and fetal hypoxia would occur, which can adversely affect subsequent organogenesis and fetal development. One effect of anemia and hypoxia, ie, placentomegaly, can be detected by ultrasonography in some fetuses as early as the 10th week of gestation (see section on Prenatal Diagnosis by Ultrasonography).52 In one series, 17% of affected newborns were found to have congenital anomalies.5They included hydrocephaly and microcephaly, as well as cardiopulmonary, skeletal, and genitourinary malformations. In another survey of 65 affected newborns in Thailand, severe reduction in brain weight was noted in some.10 Hypoplasia of lung, thymus, adrenals, and kidneys has been observed.53 Anomalous genitalia were present in other infants.53-55 Recently, limb reduction defects such as absence of hand and forefoot were reported.55-57 57a

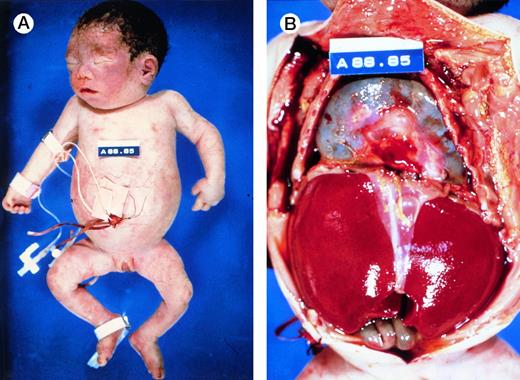

At birth, these newborns are usually pale, large and edematous, sometimes with anasarca. However, not all affected newborns are grossly hydropic (Fig 4A), illustrating the wide spectrum of clinical presentations of this disorder. Often, there are signs of high output heart failure, such as cardiomegaly, pericardial effusion (Fig 4B), pleural effusion, and ascites. The placenta is massively enlarged.5

Autopsy photographs of a newborn with hemoglobin Bart's hydrops fetalis syndrome, delivered by caesarean section at 31 week of gestation.59 Despite active resuscitation, the infant died within an hour after birth. Note edema of face and abdominal distension (A). The thoracic cavity is filled by the pericardial sac distended by effusion and cardiomegaly; there is massive hepatomegaly (B). Pictures courtesy of Prof H.A. Heggtveit.

Autopsy photographs of a newborn with hemoglobin Bart's hydrops fetalis syndrome, delivered by caesarean section at 31 week of gestation.59 Despite active resuscitation, the infant died within an hour after birth. Note edema of face and abdominal distension (A). The thoracic cavity is filled by the pericardial sac distended by effusion and cardiomegaly; there is massive hepatomegaly (B). Pictures courtesy of Prof H.A. Heggtveit.

Maternal Complications

There is an increased incidence of serious maternal complications in these pregnancies. It is likely that the placentomegaly is one important causative factor. It was estimated that half of these women could die from complications resulting from these pregnancies if there was no medical care.10 In a study of 46 women who were pregnant with affected fetuses, 61% developed hypertension during pregnancy, of whom half developed severe pre-eclampsia.5Polyhydramnios was present in 59% of the cases. Eleven percent suffered antepartum hemorrhage as a result of either unknown cause or placenta previa. Other less common complications included disseminated intravascular coagulation, renal failure, and pleural effusion. Oligohydramnios, abruptio placenta, premature labor, and congestive heart failure have also been reported.53,54 58

The mean gestation at delivery was 31 weeks with a range of 24 to 38 weeks.5 Malpresentation of the infant during births occurred in 37% of the cases. Thirty-eight women delivered vaginally, 10 of whom experienced difficulty including 3 necessitating paracenteses to decrease fetal ascites to facilitate delivery. Caesarean section was performed in 8 women. Post-partum complications include retained placenta, hemorrhage, life-threatening hypertension, puerperal pyrexia, and anemia.6,54 59

THE ONTARIO EXPERIENCE

The Province of Ontario has a population of eleven million people. There are 600,000 people of southeast Asian origins, such as China, Hong Kong, Laos, the Philippines, Taiwan, and Vietnam. It is estimated that annually in Ontario there are approximately 20 to 60 pregnancies at risk for having fetuses with the Hb Bart's hydrops fetalis syndrome.

From 1989 until 1997, the DNA Diagnostic Laboratory in Ontario has performed prenatal tests for 50 pregnancies at risk of the syndrome.60 Three of these pregnancies were at risk for both hydrops fetalis and Hb H disease. More than half (30/50) were conducted on chorionic villus samples obtained during the first trimester of pregnancy, while the remainder were on amniotic fluid or amniocyte cultures obtained during the second trimester. Eleven fetuses with homozygous α0-thalassemia were diagnosed, whereas 26 were carriers of α0-thalassemia, 2 were carriers of α+-thalassemia, and 11 were found to have the normal complement of four α-globin genes. These 50 pregnancies involved 37 couples. Only 4 couples at risk had been identified and counselled before their first pregnancy. Fifteen couples were found to be at risk during their pregnancies. As many as half of the couples referred were found to be at risk after they had one or more pregnancies ended with hydropic newborns. These observations indicate the grossly inadequate preconception carrier screening for α-thalassemia in Ontario.

For the same period (1989-1997), there should have been several hundred pregnancies at risk in Ontario. These figures indicate that despite the availability of hospital-based genetic services, only 10% to 30% of the at risk pregnancies in Ontario are identified and provided with genetic counseling and diagnostic services. In the same period, the Laboratory was called on to confirm 16 cases of hydrops fetalis caused by α-thalassemia. Three cases were diagnosed by ultrasound examination, and later confirmed by DNA testing of fetal blood obtained by cordocentesis. The remaining 13 cases were diagnosed by DNA testing of cord blood at birth or fetal tissue obtained at autopsy.

The correct diagnosis of homozygous α-thalassemia was sometimes missed at autopsy of affected fetuses. In one case, the final autopsy diagnosis was incorrectly ascribed to congenital heart disease. In another case, the woman later became pregnant again and was found to have an affected fetus again in the 24th week of the second pregnancy. These observations suggest that the numbers of pregnancies with this syndrome reported are likely to have been underestimated. Furthermore, incorrect diagnosis can adversely affect the maternal health care provided for subsequent pregnancies.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS OF SURVIVING INFANTS

Counseling, Prevention, and Care for the Pregnant Woman

With very rare exceptions (see section below), all fetuses with the Hb Bart's hydrops fetalis syndrome succumb to severe fetal hypoxia in utero during the third trimester of gestation or within hours after birth.9-11 The health care measures to combat this inevitably fatal disorder should be aimed at identifying couples at risk in order to provide them with timely counseling, and prenatal diagnosis during early pregnancy. The screening tests to detect couples at risk are simple blood counts and hemoglobin electrophoresis that are widely available (see section on Carrier Detection and Prenatal Diagnosis).

When such pregnancy is not diagnosed until the second trimester or later, the emphasis should be to ensure the well-being of the pregnant woman before and after delivery. When the diagnosis of an affected fetus is confirmed, termination of the pregnancy should be possible when requested by the pregnant woman, regardless of the stage of the pregnancy.61

Postdelivery or Intrauterine Transfusions

There are now at least six surviving children born with homozygous α-thalassemia.55,62-67 These newborns either were transfused immediately postdelivery or received intrauterine transfusions. Their clinical courses are summarized in Table2. All six children have been maintained on a regular transfusion program, and iron chelation when appropriate, similar to that for children with β-thalassemia major.68-70 Bone marrow transplantation is a possible future treatment modality for some. With proper medical therapy and patients' compliance, significant progress has been made in the survival of β-thalassemia major patients, and similar prognosis is anticipated for these six children with homozygous α-thalassemia.68-70 There are three other reports of intrauterine transfusion to treat hydropic fetuses caused by α-thalassemia.41,71 74

Summary of the Six Surviving Children Born With Homozygous α-Thalassemia

| Previous Birth of Hydropic Infant . | Birth . | Transfusion Treatment . | Duration in Hospital After Birth . | Follow-Up . | References . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Caesarean section at 32 wk | Postdelivery transfusion | 48 d | At 6 yr, delay in speech and hearing | 62, 64 |

| Yes | Caesarean section at 28 wk | Postdelivery transfusion | 73 d | At 5 yr, normal development | 63, 64 |

| Not recorded | Vaginal delivery with breech presentation at 28 wk | Postdelivery transfusion | 64 d | At 10 mo, mild gross motor delay | 64 |

| No | Caesarean section at 31 wk, as part of triplet delivery | Postdelivery transfusion | 2½ mo | At 2 yr, spastic quadriplegia and profound developmental delay | 65 |

| Yes | Caesarean section at 34 wk | Intrauterine transfusion beginning at 25 wk | 11 d | Several congenital anomalies. At 2 yr, developmental delay in cognitive and motor functions | 55, 66 |

| No | Caesarean section at 37 wk | Intrauterine transfusion beginning at 32 wk | 30 d | At 3 yr, normal neurological assessment | 67 |

| Previous Birth of Hydropic Infant . | Birth . | Transfusion Treatment . | Duration in Hospital After Birth . | Follow-Up . | References . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Caesarean section at 32 wk | Postdelivery transfusion | 48 d | At 6 yr, delay in speech and hearing | 62, 64 |

| Yes | Caesarean section at 28 wk | Postdelivery transfusion | 73 d | At 5 yr, normal development | 63, 64 |

| Not recorded | Vaginal delivery with breech presentation at 28 wk | Postdelivery transfusion | 64 d | At 10 mo, mild gross motor delay | 64 |

| No | Caesarean section at 31 wk, as part of triplet delivery | Postdelivery transfusion | 2½ mo | At 2 yr, spastic quadriplegia and profound developmental delay | 65 |

| Yes | Caesarean section at 34 wk | Intrauterine transfusion beginning at 25 wk | 11 d | Several congenital anomalies. At 2 yr, developmental delay in cognitive and motor functions | 55, 66 |

| No | Caesarean section at 37 wk | Intrauterine transfusion beginning at 32 wk | 30 d | At 3 yr, normal neurological assessment | 67 |

These newborns often had serious neonatal complications. Some also had congenital anomalies and delays in cognitive and motor functions. There are ethical issues with regards to aggressive medical intervention in fetuses who might harbor undiagnosed and possibly irreparable developmental abnormalities caused by severe fetal hypoxia in utero early during embryogenesis, and who would normally succumb to their serious genetic defects.66 The high costs of such a treatment program in light of the other societal needs and demands for health care also deserve careful thought and discussion.66

In Utero Hemopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation

Intrauterine hemopoietic stem cell transplantation has been proposed as another treatment alternative.72 Such a procedure was performed in at least three pregnancies, all without success.73-75 The ethical and societal issues raised in the previous paragraph also apply to this form of medical intervention.

CARRIER DETECTION AND PRENATAL DIAGNOSIS

Screening for Couples at Risk

Ethnic origins.

This syndrome is found almost always in couples of southeast Asian ancestry. Nevertheless, it has also been reported in the Mediterranean populations.28-35 In practice, any person found to have low erythrocyte mean corpuscular volume (MCV; see following section) without iron deficiency should be considered a carrier of either α- or β-thalassemia mutation.76-78 History of previous births of hydropic infants in a southeast Asian family should alert the physician to the likely possibility of α-thalassemia being present in the family.

Low erythrocyte MCV.

The most important diagnostic criteria to detect thalassemia carriers are microcytosis (MCV <80 fL) or hypochromia (mean corpuscular hemoglobin [MCH] <27 pg).9,77 78 In our laboratory, the mean and SD of MCV and MCH for (--SEA/αα) carriers are 67.8 ± 3.3 fL and 21.8 ± 1.2 pg, respectively. These laboratory results should be routinely reported and included as part of the prenatal screening records of all pregnant women.

On the other hand, adult carriers of two α-globin gene deletion such as (--SEA/αα) usually do not have significant anemia.9 Our laboratory has found that the hemoglobin levels for these men are 135 ± 10 g/L, and for women 121 ± 10 g/L. Therefore, it behooves all physicians caring for people during their adolescence or reproductive years to pay attention not only to the hemoglobin values, but also to the MCV or MCH results. If one partner of a couple is found to have microcytosis, the other partner should be tested to determine if he/she also has microcytosis. If both have microcytosis without iron deficiency, they should be investigated further to determine if they are at risk for conceiving fetuses with either Hb Bart's hydrops fetalis syndrome or β-thalassemia major.77 78

Hemoglobin electrophoresis.

Hemoglobin electrophoresis and Hb A2 levels are often performed as part of the laboratory investigations to diagnose thalassemia carriers. If the Hb A2 level is elevated (>3.5%), the individual is considered to be a carrier of β-thalassemia mutation. If the Hb A2 level is normal or low, the person is considered to be a carrier of α-thalassemia mutation.77,78 However, among people with microcytosis and high Hb A2 levels, some are carriers of both α- and β-thalassemia mutations.8,18 78a Of the 10 people diagnosed by our laboratory to be heterozygous carriers of both the (--SEA) α-thalassemia deletion and a β-thalassemia mutation, their mean MCV is 72.3 fL (range, 66.9 to 78.4), and Hb A2 level is 5.4% (range, 4.5 to 7.1). Therefore, the α-globin genotypes should be determined in all individuals who are referred for investigation as possible thalassemia carriers.

Hb H inclusion bodies.

In adults carriers of α-thalassemia mutations, there are excess β-globin chains within their erythroid cells. These β-globin chains can form homotetrameric Hb H (β4) precipitates (inclusion bodies) on incubation with a redox agent such as brilliant cresyle blue dye.79 The search for these inclusions is laborious and the results are highly observer-dependent. Recent studies have suggested that an immunocytological assay for embryonic ζ-globin chains (see below) or a polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based DNA diagnostic technique can serve as alternative screening procedures.80 81

Embryonic ζ-globin chains.

Adult carriers of the (--SEA) deletion have a very minute amount of the embryonic ζ-globin chains in their erythrocytes, demonstrable by immunologic techniques with anti-human-embryonic-ζ-globin-chain antibodies.82-87 In particular, the immunocytological staining of peripheral blood smears with the antibody has been shown to be highly sensitive and specific in detecting adult carriers of the (--SEA) deletion.60,84 87

Adult carriers of the large deletions such as the (--FIL) deletion do not have detectable ζ-globin chains in their erythrocytes.87 If both partners are found to be negative for the ζ-globin assay, it is unlikely that they will conceive a fetus with the Hb Bart's hydrops fetalis syndrome. Even if the embryo did inherit both parental deletions, it should result in an early miscarriage caused by the demise of the affected embryo.25If both partners have microcytosis and only one is positive for the ζ-globin chain assay, both individuals then need to have definitive DNA analysis to determine whether they are at risk of conceiving fetuses with the Hb Bart's hydrops fetalis syndrome.87

Definitive Diagnosis by DNA Analysis for Couples at Risk

For genetic counseling and prenatal diagnosis, it is essential to document the parental mutations at the DNA level either by Southern blot analysis or by PCR-based strategies.60 There are several PCR-based diagnostic protocols designed to identify the (--SEA) and other α-thalassemia deletions.88-93 The diagnostic specificity of the PCR techniques has to be rigorously maintained in view of recent reports of misdiagnoses based on this strategy.94 95

Prenatal Diagnosis by DNA or Hemoglobin Analysis

Fetal tissue samples for DNA-based prenatal diagnosis are usually obtained by chorionic villus biopsy (CVS) during 10 to 11 weeks of pregnancy, or by aminocentesis during 16 to 20 weeks of pregnancy. The risk for miscarriage in CVS is estimated to be 1.0%, and that for amniocentesis to be 0.5%. Recently, a noninvasive method to obtain fetal nucleated erythroblasts from maternal blood early in pregnancy was reported.96 97 In all prenatal diagnoses, the possibility of maternal tissue/blood contamination has to be guarded against. In some instances, nonpaternity can also be a confounding problem.

Fetal blood samples can be obtained by cordocentesis during the second trimester of gestation. Both the DNA-based analysis and hemoglobin electrophoresis can be performed on these blood samples. The major hemoglobin found in a normal fetus during the second trimester of gestation is Hb F (α2γ2), with 10% or less of Hb A (α2β2). In a fetus with homozygous α-thalassemia, the major hemoglobin is Hb Barts (γ4), with 10% to 20% of Hb Portland 1 (ζ2γ2), and possibly some Hb H (β4). Hb F or Hb A are not present in these fetuses. These results can be obtained rapidly by using simple cellulose acetate electrophoresis. Similarly, cord blood samples obtained at delivery and uncontaminated by maternal blood can be used to genotype the newborn.

Prenatal Diagnosis by Ultrasonography

After the 20th week of gestation, ultrasound examination can readily detect the many hydropic changes found in fetuses with the Hb Bart's hydrops fetalis syndrome.54,98-101 A recent study reported that hydropic changes in some fetuses could be detected as early as the 12th week of gestation.102

In a large study it was reported that increases in placental thickness in some affected fetuses occurred as early as the 10th week of gestation.52 By the 12th week, these measurements could identify most of the affected pregnancies. By the 18th week, the measurement could identify all affected pregnancies with a high specificity. These results were recently independently confirmed.103

Fetal cardiothoracic ratio measurements were also useful to diagnose affected fetuses.104 Taken together, ultrasound findings of both placentomegaly and cardiomegaly at 12 to 14 weeks of gestation can be highly specific for affected fetuses in pregnancies at risk.105 These measurements merit consideration as the next best alternative to diagnose hydropic fetuses, particularly in places where Hb Bart's hydrops fetalis syndrome is common and where DNA-based prenatal diagnosis is not readily available.

SUMMARY

Recent advances in molecular genetics have provided insights into the mutations and pathophysiology causing α-thalassemias, as well as definitive clinical diagnostic tests for adult carrier detection and prenatal diagnosis. Hydrops fetalis caused by α-thalassemia is found primarily though not exclusively among couples of southeast Asian origin, and is encountered in increasing numbers in North America and elsewhere.61,71,106-109 109a These pregnancies inevitably result in fetal death during the third trimester of gestation or shortly after birth, and frequently are associated with serious maternal morbidity and even mortality.

Presently, most couples at risk for conceiving fetuses with this serious genetic disorder are not identified. Other at risk couples are recognized only after the birth of one or more hydropic newborns, or hydrops fetalis is detected by ultrasonography during the second trimester of a pregnancy. The correct diagnosis of these hydropic fetuses is sometimes missed at autopsy. After experiencing the horrendous obstetrical, medical, and psychosocial problems associated with such pregnancies, many couples would decide against becoming pregnant again, and some would even request sterilization.61

A recurring theme of the many case reports of this syndrome is that the correct diagnosis could have been made early in pregnancy, should the physicians have been alert to this diagnostic possibility.26,53,54,57-59,61-67,71 106-117 They reaffirm the need for public education, both for the medical community and for the population at large. Blood counts are often performed as part of the medical examinations, particularly on all pregnant women during their first visits to physicians. A low MCV result is the screening test for carriers of the thalassemias.

With carrier detection, timely genetic counseling, and the availability of prenatal diagnosis during early pregnancy, many couples at risk will be spared of serious medical and psychological ordeals in their quest for having families with children. It is therefore essential that this genetic disorder is recognized, so that the appropriate maternal health care and preventive measures can be provided to the affected couples and communities.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We wish to dedicate this review to the memory of the late Professor W.H.C. Walker. His foresight, encouragement, and support were pivotal in the establishment of the Provincial Hemoglobinopathy DNA Diagnostic Laboratory. We are also indebted to our many clinical and laboratory colleagues in Ontario and elsewhere for their advice and collaboration, to Barry Eng, Margaret Patterson, and Shi-Ping Cai for their excellent technical assistance, and to Lynne Lacey for her help in the preparation of this manuscript.

Supported in part by the Medical Research Council of Canada, Cooley's Anemia Foundation of New York, the US National Institutes of Health (D.H.K.C.), the Ontario Thalassemia Foundation (J.S.W.), and the Ontario Ministry of Health.

Address reprint requests to David H.K. Chui, MD, Department of Pathology, Room 2N31, McMaster University Medical Centre, 1200 Main St W, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada L8N 3Z5.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked "advertisement" is accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal