Abstract

Despite its name, the actin-binding protein lymphocyte-specific protein1 (LSP1) is found in all hematopoetic cells, and yet its role in cell function remains unclear. Recently, LSP1 was identified as the 47-kD protein overexpressed in the polymorphonuclear neutrophils of patients with a rare neutrophil disorder, neutrophil actin dysfunction with abnormalities of 47-kD and 89-kD proteins (NAD 47/89). These neutrophils are immotile, defective in actin polymerization in response to agonists, and display distinctive, fine, “hairlike” F-actin-rich projections on their cell surfaces. We now show that overexpression of LSP1 produces F-actin bundles that are likely responsible for the morphologic and motile abnormalities characteristic of the NAD 47/89 phenotype. Coincident with LSP1 overexpression, cells from each of several different eukaryotic lines, including a highly motile human melanoma line, develop hairlike surface projections that branch distinctively and contain F-actin and LSP1. The hairlike projections are supported at their core by thick actin bundles, composed of actin filaments of mixed polarity, which periodically anastomose to generate a branching structure. The motility of the melanoma cells is inhibited even at low levels of LSP1 expression. Therefore, these studies show that overexpression of LSP1 alone can recreate the morphologic and motile defects seen in NAD 47/89 and suggest that LSP1 is distinct from other known actin binding proteins in its effect on F-actin network structure.

LYMPHOCYTE-SPECIFIC protein 1, also called LSP1, is a 52- to 54-kD protein originally identified in murine lymphocytes1,2 and subsequently found in hematopoetic cells, including human polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs) and monocytes.3 LSP1 is postulated to be a cytoplasmic actin-binding protein because it binds F-actin in vitro4 and, in murine lymphocytes, LSP1 is found in the triton insoluble cytoskeleton and cocaps with the IgM receptor.5 However, the in vivo functions of the protein remain largely unknown.

In 1994, LSP1 was identified as the 47-kD protein overexpressed in PMNs from patients with a novel neutrophil motility disorder, neutrophil actin dysfunction with 47-kD and 89-kD protein abnormalities (NAD 47/89).6,7 These patients suffer from recurrent bacterial infections caused by functionally impaired neutrophils deficient in several motile behaviors, including random and directed migration, phagocytosis, and spreading on glass. In situ, NAD 47/89 neutrophils fail to increase actin polymerization in response to chemotactic factors and, perhaps most strikingly, display numerous thin, hairlike, F-actin rich filamentous projections on their plasma membrane surfaces.6

The discovery that LSP1 is overexpressed in these neutrophils implied that the protein might be responsible for the morphologic and motile abnormalities of these cells. To investigate this hypothesis, and thus possibly shed light on the protein's in vivo function, human LSP1 was expressed in several eukaryotic cell lines and its effect on cell morphology and motility was assayed. We found that in all cell lines, the expression of LSP1 led to the emergence on the cells of multiple, thin, hairlike projections morphologically similar to those observed on NAD 47/89 PMNs. Projections are highly enriched for LSP1 and contain tightly packed bundles of actin filaments that have unique branching architecture. In addition, expression of LSP1 inhibited the locomotion of normally motile human melanoma cells. Thus, the changes in morphology and motility found in the cells expressing LSP1 duplicate the phenotypic characteristics of PMNs in the NAD 47/89 syndrome, making it the first disorder of human PMN motility caused by a defined abnormality in an actin binding protein. The results also suggest that LSP1 acts as an actin filament bundling protein in vivo, and is capable of promoting unique actin bundle-based cytoskeletal architecture.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

The eukaryotic (pMEP and pREP), and baculoviral (pBlueBacHisC) expression vectors and Ni2+ affinity columns were purchased from Invitrogen (San Diego, CA); the baculovirus used for recombination was purchased from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA). All other supplies were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co (St Louis, MO), unless otherwise noted.

Generation of recombinant baculoviruses.

The LSP1 cDNA was cloned into the pBlueBacHisC baculoviral recombination vector at the BamHI, HindIII sites and shown to be in frame with the gene and the six histidines in the N-terminal leader sequence by dideoxy sequencing.8-10 The resultant plasmid (pBlueBacHisC-LSPl) was expanded and purified for cotransfection with linearized BacPak6 (BstIe) into Sf9 insect cells (5 μg DNA of each vector) in serum-free medium for 2 hours as per the manufacturer's instructions.9-12 The infected cells were then overlaid with Xgal impregnated agarose and plaques observed over 7 days for the development of blue color, indicating β-galactosidase activity. Blue clones were picked, serially expanded, and titered by limiting dilution. A control baculovirus which expresses chloramphenicol acetyl transferase (CAT) with the same N-terminal polyhistidine leader sequence was also prepared by infecting Sf9 with linearized pBacPak6 (BstIe) virus and the CAT cDNA cloned into pBlueBacHisC (each 5 μg) followed by screening for β-galactosidase positive recombinants under agarose.

LSP1 expression in Sf9 cells.

For bulk preparation of LSP1, the recombinant human LSP1 (huLSP1) were expressed as a polyhistidine fusion protein, thus allowing purification by Ni2+-affinity chromatography.9,13,14Briefly, 500-mL cultures of 106 cells/mL of Sf9 cells in spinner bottles were infected with 5 plaque-forming units (pfu)/cell, cultured for 48 hours, then obtained as pellets from 50-mL aliquots of suspension. Lysing a small aliquot of cells, separating the polypeptides by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and immunoblotting documented the expression of LSP1 or CAT.15 16

Immunoblot and immunofluorescence.

Immunoblots of cells and purified protein samples were performed with monoclonal and polyclonal anti-human LSP17 in accordance with the method of Towbin et al16 or by chemiluminescence. For immunofluorescence microscopy, cells were fixed with 3.2% formaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.25% Triton X-100. LSP1 was localized by incubating with IgG1 mouse monoclonal anti-huLSP1 primary antibody followed by fluorescein tagged goat anti-mouse IgG secondary. Intracellular F-actin was visualized by staining with rhodamine phalloidin (0.67 × 10-7mol/L) (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Cell staining was visualized and photographed on a Leitz Optiphot microscope (Wetzlar, Germany) equipped for epifluorescence.

Electron microscopy: Rapid-freezing and freeze-drying.

Cells were permeabilized with PHEM-0.75% Triton X-100 buffer17 containing 5 μmol/L phallacidin and protease inhibitors for 2 minutes at 20°C, and then the adherent cytoskeletons washed twice in PHEM buffer containing 0.1 μmol/L phalloidin and fixed in PHEM containing 1% glutaraldehyde for 10 minutes. The cytoskeletons were extensively washed with distilled water, rapidly frozen, freeze-dried at −80°C, and rotary coated with 1.4 nm of tantalumtungsten and 2.5 nm of carbon in a Cressington CFE-50 apparatus (Cressington Inc, Watford, UK).18

Labeling of cytoskeletons with myosin S1.

Coverslips with adherent cytoskeletons were prepared as described above in the presence of phallacidin but without fixation. The coverslips were incubated with 5 μmol/L skeletal muscle myosin S1 in PHEM for 10 minutes at room temperature, washed twice with PHEM buffer, and then fixed with a solution of 0.2% tannic acid, 1% glutaraldehyde, and 10 mmol/L sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.5. They were rapidly frozen, freeze-dried, and metal coated as described above.

Negative stain electron microscopy (EM) of purified Sf9 cell projections.

The filamentous projections on Sf9 cells expressing huLSP1 were purified from 48-hour cultures of Sf9 cells infected at multiplicity of infection 5 pfu/cell with recombinant baculovirus. Cells were gently washed from tissue culture flasks, then passed through a 29-gauge needle four times with constant pressure. The shearing process was monitored by phase and differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy. Sf9 cell bodies were sedimented by 10-minute centrifugation at 500g. The hairlike filamentous projections were then sedimented from the 500g supernatant by 13,000g × 5-minute centrifugation and careful removal of all except the last drops of supernatant. The hairlike projections were resuspended in PHEM. DIC and phase microscopy showed enrichment of hairlike projections that were then processed for negative staining with 2% uranyl acetate with or without prior Triton X-100 treatment.19

LSP1 expression in COS cells and A7 melanoma cells.

To express huLSP1 in CV1-COS cells (LSP1 negative by immunoblot and immunofluorescence in the nontransfected state), the huLSP1 cDNA was cloned into pCDM8 expression vector, which allows high levels of transient expression,20 and pCDM8 vector alone (25 μg CsC1 purified pCDM8) or the pCDM8 vector with huLSP1 (25 μg CsC1 purified pCDM8-huLSP1) was transfected by calcium phosphate precipitation into CV1-COS cells at low density. The cells were cultured for 48 to 72 hours and then analyzed by indirect immunofluorescence for huLSP1.

To express huLSP1 in human cells, the LSP1-negative human A7 melanoma cells were used.21 The full-length huLSP1 cDNA was cloned into both the pMEP mammalian expression vector, which places expression under the control of the divalent metal (Zn2+) inducible metallothionein promoter, and the pREP constitutive expression vector. Control transfection using pREP or pMEP alone were also performed. Resistant clones from each transfection were expanded and checked for LSP1 expression by quantitative immunoblots with anti-LSP1. To induce increased LSP1 expression in the cells transfected with pMEP-LSP1, 50-50-100 μmol/L ZnSO4 was added to the cell media and the cells incubated for 4 to 8 hours.22-25

Motility assays in A7 melanoma cells.

Migration through a nucleopore membrane in response to a chemoattractant was assayed as previously described with the use of a 48-well, two-compartment chamber (Nucleopore, Pleasanton, CA).21 In each assay the bottom wells of the chamber were filled with either cell-conditioned media or buffer, then 5 × 104 cells suspended in serum-free media were loaded into the top wells with a polycarbonate membrane with 5 μm uniform pore size as the barrier between the two wells. After a 3-hour incubation at 37°C, the membrane was removed from the chamber and scraped on the top well side to remove adherent cells. The cells on the other side of the membrane were then those that had migrated through the membrane during the incubation period and were stained, and counted for each well on a Nikon inverted microscope (Tokyo, Japan) with a ×10 objective. All values are given as the average of at least eight determinations ± SEM for each condition.

RESULTS

Human LSP1 expression in Sf9 cells induces filamentous projection formation.

Sf9 insect cells were transfected with a recombinant baculovirus expressing human LSP1 as a fusion protein with six histidines at the amino terminal end to allow purification by Ni2+ affinity chromatography. Protein expression was verified by LSP1 immunoblotting of cell lysates (Fig 1). Separate control inoculations were also performed using a recombinant baculovirus expressing CAT with the identical amino terminal polyhistidinylated leader sequence found in the LSP1 vector. Cell lysates from these control inoculations were negative for LSP1 by immunoblotting (Fig 1).

Time course human LSP1 expression in Sf9 cells infected with recombinant huLSP1 baculovirus. Shown are immunoblots with anti-huLSP1 of PMNs (P) and Sf9 cells infected with either recombinant CAT baculovirus (CAT) or recombinant huLSP1 baculovirus (LSP1) for 0, 24, 36, and 48 hours. The recombinant huLSP1 is 66 kD, the native protein is 54 kD on this 10% SDS polyacrylamide gel.

Time course human LSP1 expression in Sf9 cells infected with recombinant huLSP1 baculovirus. Shown are immunoblots with anti-huLSP1 of PMNs (P) and Sf9 cells infected with either recombinant CAT baculovirus (CAT) or recombinant huLSP1 baculovirus (LSP1) for 0, 24, 36, and 48 hours. The recombinant huLSP1 is 66 kD, the native protein is 54 kD on this 10% SDS polyacrylamide gel.

Forty-eight to 72 hours after inoculation with LSP1 baculovirus, 65% to 80% of the Sf9 cells develop extensive, hairlike projections from the surface of the cells as shown in Fig 2B and C. These filamentous projections are thin (0.1 to 0.3 μm diameter) and branch extensively. At many points along their length and at their ends, the filamentous projections are decorated with small nodes or bumps. The projections are F-actin rich and LSP1 colocalizes with the F-actin (Fig 3) in the projections. In contrast, no hairs were observed in CAT-vector infected cells (Fig 2A).

Human LSP1 expression in Sf9 cells causes formation of hairlike, filamentous projections. Shown are DIC photomicrophs on Sf9 cells infected for 48 hours with either (A) recombinant CAT baculovirus or (B and C) recombinant huLSP1 baculovirus which overexpress the polyhisCAT and polyhis-huLSP1 in Sf9. Note branches (arrowhead) of hairlike projections.

Human LSP1 expression in Sf9 cells causes formation of hairlike, filamentous projections. Shown are DIC photomicrophs on Sf9 cells infected for 48 hours with either (A) recombinant CAT baculovirus or (B and C) recombinant huLSP1 baculovirus which overexpress the polyhisCAT and polyhis-huLSP1 in Sf9. Note branches (arrowhead) of hairlike projections.

F-actin and human LSP1 colocalize in hairlike projections of Sf9 cells. Shown are fluorescence photomicrographs of 48-hour huLSP1 baculovirus infected Sf9 cells double-labeled with both (A) anti-LSP1 and fluorescein-tagged second antibody and (B) rhodamine phalloidin for F-actin. Note both labels colocalize in the cells (arrowhead) and in hairs.

F-actin and human LSP1 colocalize in hairlike projections of Sf9 cells. Shown are fluorescence photomicrographs of 48-hour huLSP1 baculovirus infected Sf9 cells double-labeled with both (A) anti-LSP1 and fluorescein-tagged second antibody and (B) rhodamine phalloidin for F-actin. Note both labels colocalize in the cells (arrowhead) and in hairs.

Structure of the cytoskeleton in Sf9 cells expressing LSP1.

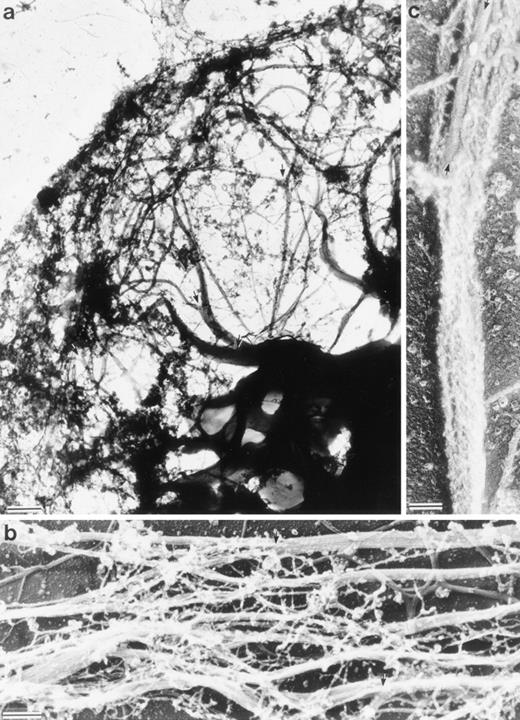

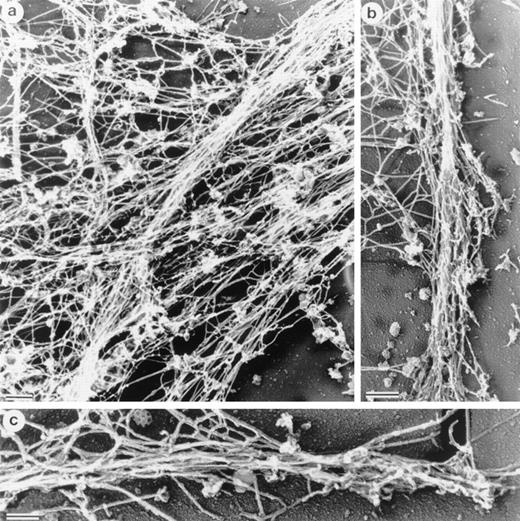

Electron micrographs of cytoskeletons from Sf9 cells infected with the human LSP1 recombinant baculovirus and prepared with Triton X-100 in the presence of phalloidin show networks of bundled 10-nm filaments (Fig 4a and Fig5a). Decoration with the myosin S1 subfragment shows that individual bundles, which can be 100 to 200 nm in diameter, are composed of tightly packed actin filaments of mixed polarity (Fig 4b and c). Most strikingly, a bundle network is formed by interbundle filament exchanges, ie, individual filaments weave in and out at branch points between bundles (Fig 5a). Large bundles tend to divide into two or three smaller bundles near the cell periphery and some of these bundles continue to form the core of the long projections that extend from the cell's surface. The filamentous projections and the interlaced pattern of F-actin bundles were not observed in Sf9 cells infected with the control CAT recombinant baculovirus (data not shown).

Structure of the Sf9 cytoskeletal bundles and hairs projected from the Sf9 cells expressing LSP1. (a) The low magnification micrograph shows a portion from a representative Sf9 cytoskeleton that had produced hairlike projections. Bundles of filaments are found through out the cytoplasm. Large bundles originate in the perinuclear region and, at many points, bundles intersect and/or branch (arrows). Sf9 cells were infected for 48 hours with recombinant huLSP1 baculovirus, attached to coverslips by centrifugation at 280g, Triton X-100 extracted, fixed, rapidly frozen, freeze-dried, and rotary coated with 1.4 nm of tantalum, tungsten, and 2.5 nm of carbon. The bar is 1 μm. (b) Higher magnification of filament bundles. Individual filaments composing the bundles have 10-nm diameters. Some bundle branch points are indicated with arrows. (c) Demonstration that the 10-nm filaments are actin using myosin S1 to decorate them. Bundles are seen to be composed of actin filaments with mixed polarity. Bundles also can contain structures which fail to bind myosin S1 (arrows). The bars in (b) and (c) are 100 nm.

Structure of the Sf9 cytoskeletal bundles and hairs projected from the Sf9 cells expressing LSP1. (a) The low magnification micrograph shows a portion from a representative Sf9 cytoskeleton that had produced hairlike projections. Bundles of filaments are found through out the cytoplasm. Large bundles originate in the perinuclear region and, at many points, bundles intersect and/or branch (arrows). Sf9 cells were infected for 48 hours with recombinant huLSP1 baculovirus, attached to coverslips by centrifugation at 280g, Triton X-100 extracted, fixed, rapidly frozen, freeze-dried, and rotary coated with 1.4 nm of tantalum, tungsten, and 2.5 nm of carbon. The bar is 1 μm. (b) Higher magnification of filament bundles. Individual filaments composing the bundles have 10-nm diameters. Some bundle branch points are indicated with arrows. (c) Demonstration that the 10-nm filaments are actin using myosin S1 to decorate them. Bundles are seen to be composed of actin filaments with mixed polarity. Bundles also can contain structures which fail to bind myosin S1 (arrows). The bars in (b) and (c) are 100 nm.

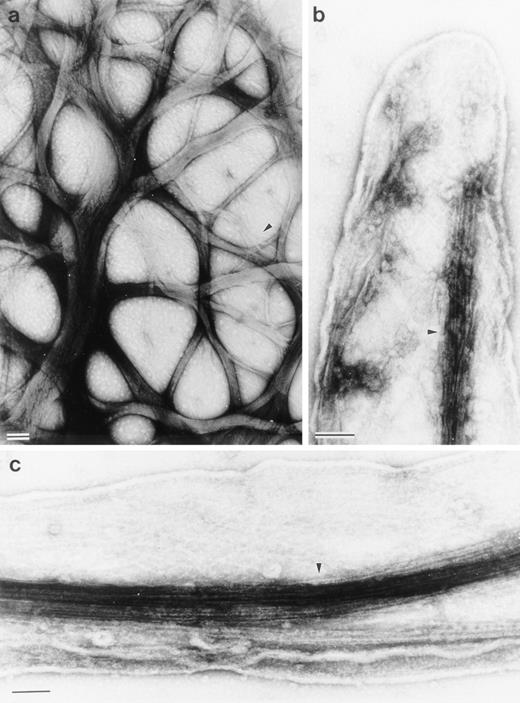

Structure of interlacing bundles of F-actin in Sf9 cells and of isolated hairlike projections. (a) Structure of cytoplasmic bundles in Sf9 cell after staining with 2% uranyl acetate. This representative micrograph shows the complexity of bundle interdigitation. Ends of bundles can be observed to splay out into their individual component filaments at many points (arrowheads). (b and c) Structure of hairlike projections. Hairs were separated from intact cells by mechanical agitation and centrifugation. Hairs are bound by membrane and are cored by organized filament bundles (arrowhead). Bundles abruptly end near the tips of projections (b). The bars are 100 nm.

Structure of interlacing bundles of F-actin in Sf9 cells and of isolated hairlike projections. (a) Structure of cytoplasmic bundles in Sf9 cell after staining with 2% uranyl acetate. This representative micrograph shows the complexity of bundle interdigitation. Ends of bundles can be observed to splay out into their individual component filaments at many points (arrowheads). (b and c) Structure of hairlike projections. Hairs were separated from intact cells by mechanical agitation and centrifugation. Hairs are bound by membrane and are cored by organized filament bundles (arrowhead). Bundles abruptly end near the tips of projections (b). The bars are 100 nm.

To verify that F-actin bundles form the core of the hairs that extend from these cells' surfaces, the hairlike projections were sheared with low shear forces from huLSP1 recombinant baculovirus infected Sf9 cells. The projections were purified by differential centrifugation, then were negatively stained (Fig 5b and c show the structure of these dissociated projections). Dissociated projections are membrane bound, rounded at the end, and contain one or more F-actin bundles that splay into individual 10-nm filaments at the projections' end.

Human LSP1 also creates hairs on mammalian cells.

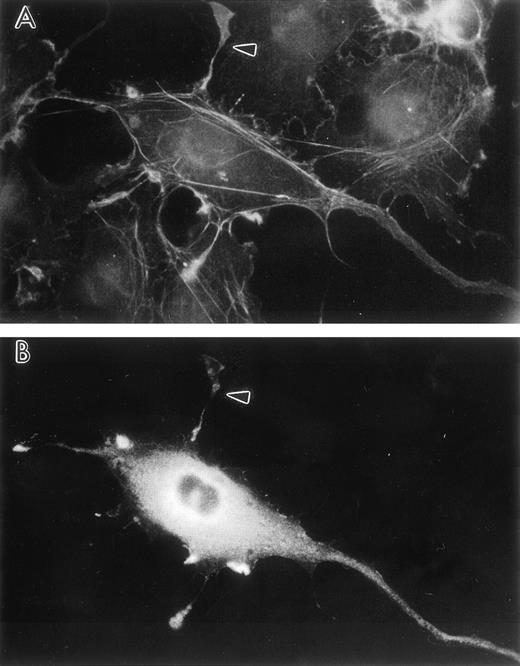

To confirm that this unique actin architecture can be induced in mammalian cells as well as invertebrate cells, the human LSP1 cDNA was cloned into the pCMD8 transient expression vector and transfected into CV1-COS cells. Sixty hours after transfection, the cells were fixed and stained for F-actin with rhodamine-phalloidin and for LSP1 by indirect immunofluorescence. Thirty percent of the pCMD8-huLSP1 transfected CV1-COS cells were LSP1 positive by indirect immunofluorescence, and these cells displayed thin, hairlike projections that stained for both F-actin and LSP1 (Fig 6).

Transient human LSP1 expression in CV1-COS cells. Shown are fluorescence photomicrographs of CV1-COS cells transiently transfected with pCMD8-huLSP1 expressing huLSP1 and double-labeled with anti-LSP1 with fluorescein tagged second antibody and rhodamine phalloidin for F-actin. Photomicrographs are (A) the rhodamine phalloidin image and (B) the huLSP1 image of the same cell. Note thin projections with F-actin and huLSP1 (arrowhead).

Transient human LSP1 expression in CV1-COS cells. Shown are fluorescence photomicrographs of CV1-COS cells transiently transfected with pCMD8-huLSP1 expressing huLSP1 and double-labeled with anti-LSP1 with fluorescein tagged second antibody and rhodamine phalloidin for F-actin. Photomicrographs are (A) the rhodamine phalloidin image and (B) the huLSP1 image of the same cell. Note thin projections with F-actin and huLSP1 (arrowhead).

Morphologic effects of LSP1 on mammalian cells depend on the level of LSP1 expression.

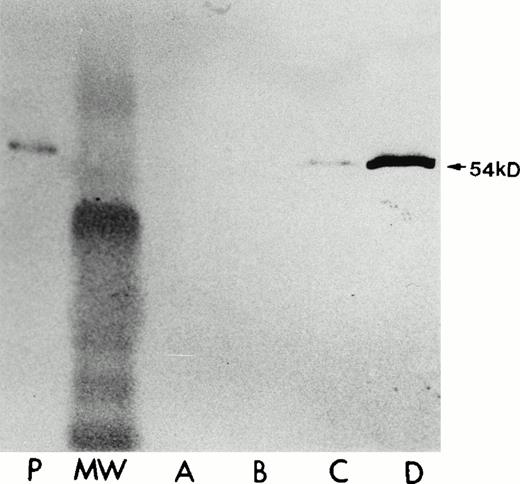

Because the expression of high levels of cellular LSP1 by transient transfection was capable of inducing the formation of hairlike projections in Sf9 and CV1-COS cells, we then investigated whether the morphologic effect depends on LSP1 level. The huLSP1 cDNA was cloned into the mammalian expression vector pMEP that encodes hygromycin B resistance and allows for selection of stably transfected cell lines. Expression by the pMEP vector is under control of the Zn2+ inducible methallothionein promoter allowing Zn2+ regulation of LSP1 level in cells.22-25The pMEP-LSP1 was transfected into the A7 melanoma cell line21 that normally does not express LSP1. Hygromycin B resistant clones were selected, expanded, and quantitated for LSP1 expression and morphology in the presence and absence of Zn2+ was observed. As a control, stably transfected A7 melanoma cells were similarly established by transfections with pMEP vector alone. As shown (Fig 7), one cell line (A7ML1) constituitively expresses low LSP1 levels (20% to 50% of the LSP1 level in PMNs) and markedly increased LSP1 levels upon exposure to Zn2+. Neither the parent A7 melanoma line nor the control A7 melanoma line transfected with the pMEP vector alone expresses LSP1 in the presence or absence of Zn2+. The A7ML1 cells with low constituitive LSP1 expression have a smooth edge interrupted only by occasional irregularities. However, after Zn2+ induction of LSP1 expression, the A7ML1 cell line develops extensive, branching surface hairlike projections (Fig 8). Therefore, the morphologic effect of human LSP1 depends on LSP1 level in cells.

Human LSP1 expression in the stably transfected A7 melanoma cells, A7ML1, in the absence/presence of Zn2+. Shown are immunoblots with anti-LSP1 of 50 μg total cellular protein from (P) PMNs, (A) parent A7 melanoma cells alone + 100 μmol/L Zn2+ for 6 hours, (B) the A7 melanoma line stably transfected with pMEP vector alone + 100 μmol/L Zn2+for 6 hours; (C and D) the A7ML1 cell line stably transfected with pMEP-huLSP1 in the absence (C) and presence (D) of 100 μmol/L Zn2+ for 6 hours. MW, molecular weight marker. The immunoblot was developed colorimetrically.

Human LSP1 expression in the stably transfected A7 melanoma cells, A7ML1, in the absence/presence of Zn2+. Shown are immunoblots with anti-LSP1 of 50 μg total cellular protein from (P) PMNs, (A) parent A7 melanoma cells alone + 100 μmol/L Zn2+ for 6 hours, (B) the A7 melanoma line stably transfected with pMEP vector alone + 100 μmol/L Zn2+for 6 hours; (C and D) the A7ML1 cell line stably transfected with pMEP-huLSP1 in the absence (C) and presence (D) of 100 μmol/L Zn2+ for 6 hours. MW, molecular weight marker. The immunoblot was developed colorimetrically.

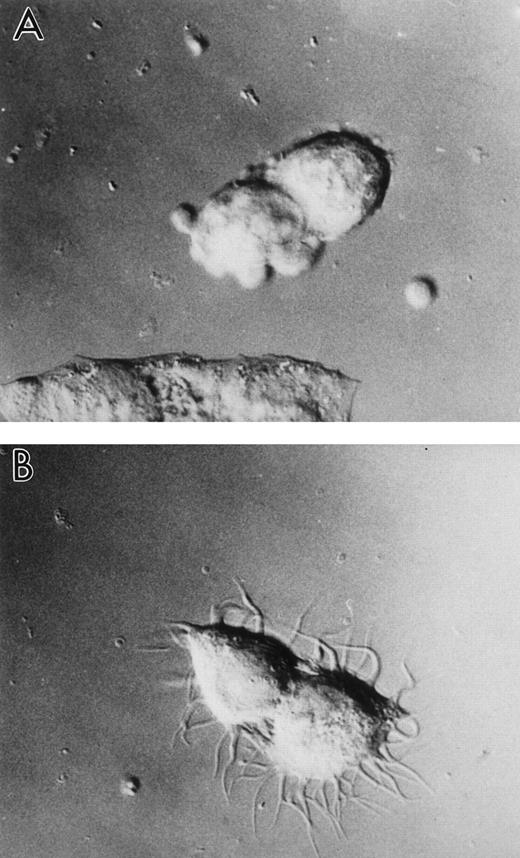

Increased level of human LSP1 causes formation of hairlike projections on A7 melanoma cell line, A7ML1. Shown are DIC photomicrographs of the A7 melanoma cell line, A7ML1, stably transfected with pMEP-huLSP1 and exposed 6 hours to (A) serum-free culture medium without Zn2+ or (B) serum-free culture medium plus 100 μmol/L Zn2+ for 6 hours. Exposure of A7 melanoma cells stably transfected with pMEP alone to Zn2+does not cause hairlike projection formation (not shown).

Increased level of human LSP1 causes formation of hairlike projections on A7 melanoma cell line, A7ML1. Shown are DIC photomicrographs of the A7 melanoma cell line, A7ML1, stably transfected with pMEP-huLSP1 and exposed 6 hours to (A) serum-free culture medium without Zn2+ or (B) serum-free culture medium plus 100 μmol/L Zn2+ for 6 hours. Exposure of A7 melanoma cells stably transfected with pMEP alone to Zn2+does not cause hairlike projection formation (not shown).

Morphology of cytoskeletons in A7 melanoma cells expressing LSP1.

Figure 9 shows the structure of actin filaments in hairlike projections formed in the LSP1 transfected A7 cell line A7ML1. With induction of protein expression by Zn2+, these cells develop multiple thin, hairlike projections as described above. The cytoskeleton of these cells exhibits some of the same branching bundles seen in the Sf9 cells, although bundle organization is considerably less uniform. However, actin filaments core the projections extended from these cells similar to those in the Sf9 cells. Like the Sf9 cells, the projections derive from the branching of actin bundles from the underlying cytoskeletal network.

Organization of cytoskeletal actin in A7ML1 cell line expressing LSP1. Electron micrographs show Zn2+ induction of LSP1 expression in the melanoma A7 cell line, A7ML1, results in the formation of cytoplasmic filament bundles and hairlike projections similar to those in LSP1 expressing Sf9 cells. (a) Filaments in the cytoskeletal bundles are not as tightly packed as those in Sf9 cells but have a similar intersecting morphology. (b and c) The structure of cytoplasmic actin within two projections. The bars are 100 nm.

Organization of cytoskeletal actin in A7ML1 cell line expressing LSP1. Electron micrographs show Zn2+ induction of LSP1 expression in the melanoma A7 cell line, A7ML1, results in the formation of cytoplasmic filament bundles and hairlike projections similar to those in LSP1 expressing Sf9 cells. (a) Filaments in the cytoskeletal bundles are not as tightly packed as those in Sf9 cells but have a similar intersecting morphology. (b and c) The structure of cytoplasmic actin within two projections. The bars are 100 nm.

Overexpression of LSP1 inhibits cell motility.

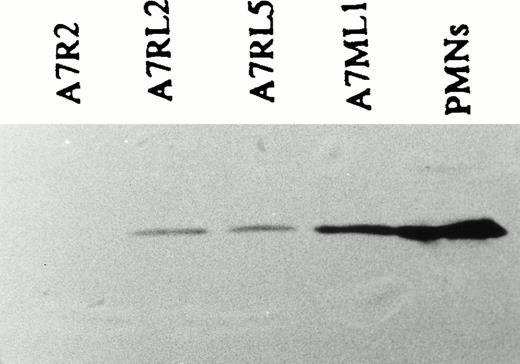

To investigate the effect of LSP1 on cell motile function we analyzed the motility of parental A7 melanoma cells and stably transfected A7 melanoma cells which constituitively express human LSP1. The cell lines used for motility studies express LSP1 either from the pMEP-LSP1 vector in the A7ML1 line described above or from a related pREP mammalian expression vector that places LSP1 expression under control of the constituitive RSV promoter in the A7RL2 and A7RL5 cell lines. The A7RL5 and A7RL2 were prepared with the pREP-LSP1 vector as described above for the A7ML1 line. As shown (Fig 10), A7ML1, A7RL5, and A7RL2 express LSP1 at levels 20% to 50% of those found in PMNs, and A7R2, a control line stably transfected with pREP vector alone, does not express LSP1. The motility of A7 cells has been well documented in a two-compartment modified Boyden chamber.21 Using this system, we compared the motility of the A7ML1, A7RL2, and A7RL5 LSP1 positive lines and control A7R2 and A7 parental cells. The number of cells able to migrate through the membrane in a 3-hour period was markedly reduced in each of the LSP1 expressing lines when compared with both the parent A7 line and the control A7R2 line (Fig 11). Note that this reduction in motility was seen in the A7ML1 line at constituitive levels of LSP1 expression. With induction of A7ML1 with Zn2+ to a twofold to fourfold increase in LSP1 expression, motility ceased completely so that no cells crossed the chamber membrane (not shown).

Expression of LSP1 in stably transfected, constituitively expressing A7 melanoma lines used to analyze motility. Shown is an anti-LSP1 immunoblot developed by chemiluminescence of equal protein loads of (P) PMNs, the stably transfected, constituitively expressing A7ML1, A7RL5, A7RL2 cell lines and a control line, A7R2, stably transfected with pREP vector alone.

Expression of LSP1 in stably transfected, constituitively expressing A7 melanoma lines used to analyze motility. Shown is an anti-LSP1 immunoblot developed by chemiluminescence of equal protein loads of (P) PMNs, the stably transfected, constituitively expressing A7ML1, A7RL5, A7RL2 cell lines and a control line, A7R2, stably transfected with pREP vector alone.

LSP1 inhibits cell motility. Shown is a comparison of uninduced A7ML1 cells, as well as the LSP1 expressing A7RL2 and A7RL5 cell lines, with the non-LSP1 expressing parent A7 cell line and a control transfected A7R2 line. Values are mean ± 1 SD from three determinations of motility using the two-compartment chemotactic chamber.21

LSP1 inhibits cell motility. Shown is a comparison of uninduced A7ML1 cells, as well as the LSP1 expressing A7RL2 and A7RL5 cell lines, with the non-LSP1 expressing parent A7 cell line and a control transfected A7R2 line. Values are mean ± 1 SD from three determinations of motility using the two-compartment chemotactic chamber.21

DISCUSSION

The NAD 47/89 phenotype is reproduced in nonhematopoetic cells by the expression of LSP1.

Although the gene defect in NAD 47/89 is not known, neutrophils from patients with NAD 47/89 syndrome are phenotypically characterized by three distinguishing features: (1) the appearance of numerous F-actin-rich filamentous projections (“hairs”) on their surface; (2) their inability to crawl in response to chemoattractants; and (3) increased levels of LSP1.3,4 In this report we have shown that the expression of LSP1 reproduces these phenotypic characteristics in a variety of eukaryotic cells. Results in transfected cells show that the increased LSP1 levels cause the motile and morphologic abnormalities in NAD 47/89 cells. Other types of F-actin-based filamentous projections including microvilli and filopodia can be found on the surface of many eukaryotic cells and have been associated with the overexpression of specific actin-associated proteins. For example, microvilli in epithelial cells are formed from the interaction of F-actin and villin, an actin bundling protein with two actin-binding domains. Villin can form microvilli when either transfected26 or microinjected27,28 into mammalian cells. However, villin expression has no effect on surface motility or cell locomotion.27 Because the expression of LSP1 to levels insufficient for hair formation led to marked inhibition of cell locomotion, it is likely that the interaction of LSP1 with actin filaments leads not only to F-actin bundling, but the results also suggest these bundles may interfere with normal actin turnover required for cell motility.

Analysis of the hairs formed by LSP1 provides clues to its interaction with actin filaments. LSP1-induced hairs are distinguished from normal microvilli or villin-induced microvilli by their long length (up to 50 μm), diameter (0.1 to 0.3 μm), and tendency to branch. Not only did cells expressing LSP1 have hairs but they also displayed an internal network of branching F-actin bundles that fuse and split to generate a unique curvilinear nodal unit linked in a three-dimensional network as illustrated in Fig 5. The results suggest LSP1 may create branching F-actin bundles. Such a network differs from the single continuous F-actin bundle formed by villin or α-actinin or the three-dimensional orthogonal network formed by ABP-280.21,27,29 How LSP1 binding to F-actin alone would create such an extensive network or where LSP1 binds along the actin filaments is not clear. Further, the induction of bundles by LSP1 suggests that this protein, if monomeric, possesses two or more actin binding sites, or self-associates to dimers or higher oligomers. One actin-binding domain in mouse LSP1 has been defined by truncation and resides in the carboxyl one-half of the protein.5 More recently a possible second and third actin-binding domains have been identified (unpublished observation, December, 1996). Bundling with purified mouse LSP1 has been previously observed in vitro, although the mouse LSP1 protein may have been aggregated by the purification procedure.5

Critically, the level of LSP1 expression that inhibits cell motility is far below that found in PMNs, which are quite motile cells, suggesting that neutrophils are able to regulate the binding of LSP1 to actin in ways not available to other cells. One intriguing possibility is that the 89-kD protein decreased in NAD 47/89 disorder may play a role in the regulation of LSP1, so that the characteristics of these neutrophils are a result of both LSP1 overexpression and 89-kD underexpression. Alternatively, LSP1 is a highly phosphorylated protein and its effect on actin may be regulated by phosphorylation. These important facts of LSP1 regulation await further elucidation.

Supported by National Institutes of Health Grant No. 1F33HL08857-01 and a National Research Service Award Senior Fellowship to T.H.H.

Address reprint requests to Thomas H. Howard, MD, University of Alabama at Birmingham, 1600 7th Ave S, Suite 651, Birmingham, AL 35233.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked "advertisement" is accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal