Abstract

Human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1) is the etiologic agent of adult T-cell leukemia and HTLV-1-associated myelopathy. Novel, yet conserved RNA transcripts encoded from open reading frames (ORFs) I and II of the viral pX region are expressed both in vitro and in infected individuals. The ORF I mRNA encodes the protein p12I, which has been shown to localize to cellular endomembranes, cooperate with bovine papillomavirus E5 in transformation, as well as bind to the IL-2 receptor β and γ chains and the H+ vacuolar ATPase. It is unknown what role p12I plays in the viral life cycle. Using an infectious molecular clone of HTLV-1 (ACH) and a derivative clone, ACH.p12I, which fails to produce the p12Imessage, we investigated the importance of p12I in infected primary cells and in a rabbit model of the infection. ACH.p12I was infectious in vitro as shown by viral passage in culture and no qualitative or quantitative differences were noted between ACH and ACH.p12I in posttransfection viral antigen production. However, in contrast to ACH, ACH.p12I failed to establish persistent infection in vivo as indicated by reduced anti-HTLV-1 antibody responses, failure to demonstrate viral p19 antigen production in peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) cultures, and only transient detection of provirus by polymerase chain reaction in PBMC from ACH.p12I-inoculated rabbits. These results are the first to show the essential role of HTLV-1 p12I in the establishment of persistent viral infection in vivo and suggest potential new targets in antiviral strategies to prevent HTLV-1 infection.

HUMAN T-CELL lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-1) has been identified as the causative agent of adult T-cell leukemia and appears to initiate a variety of immune-mediated disorders including the chronic degenerative disease, HTLV-1-associated myelopathy/tropical spastic paraparesis.1,2 This complex retrovirus contains, in addition to the typical retroviral structural genes gag, pol, and env, several regulatory genes. These regulatory genes are derived from four open reading frames (ORFs) in the pX region located between env and the 3′ LTR. ORFs IV and III encode the well-characterized Tax and Rex proteins, respectively.3Tax, a 40-kD transactivating protein has been implicated in viral pathogenesis, in part, by dysregulation of a number of important regulatory cellular proteins including CREB/ATF, NF-κB, SRF, and p16INK.4 Rex, a 27-kD phosphoprotein, is critical in RNA processing and the production of viral structural proteins.5 Less clear is knowledge of host factors and other viral genes important in establishment and pathology of persistent HTLV-1 infections.

It is uncertain what role, if any, pX ORFs I and II play in viral replication or pathogenesis. Several groups have identified conserved ORF I and II mRNA species by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and RNAase protection assay in HTLV-1-infected cells and individuals, but have been unable to show expression of protein encoded by these messages.6-9 However, expression of protein, including p12I, p13II, and p30II, has been achieved upon transfection of ORF I- and II-containing plasmids into eukaryotic cells.7,8,10 The p12I protein has been shown to be highly hydrophobic and localized to cellular endomembranes.10 This 99-amino acid protein contains four SH3 binding motifs, cooperates with bovine papillomavirus E5 in transformation, associates with the H+vacuolar adenosine triphosphatase (ATPase), and may decrease expression of the interleukin-2 receptor (IL-2R) β and γc chains.11-13

Despite the evidence for p12I functionality, the role of this protein in the viral life cycle has not been established, although recent evidence suggests that the p12I message is not required for viral infectivity, replication, or transformation in vitro (Michael Robek et al, personal communication, October, 1997). However, large deletions of regions in bovine leukemia virus and HTLV-2 analogous to HTLV-1 ORF I and II resulted in lower viral loads in vivo, although no deleterious effect on virus production or transforming capacity was detected in vitro.14-16 We have recently shown a full-length clone of HTLV-1, designated ACH, to be infectious in vitro and in vivo in a rabbit model.17 By using ACH and a derivative clone in which the splice acceptor site for the third exon of the ORF I message is destroyed, we examined the specific role of p12I in viral replication and infectivity in vitro and in vivo. Upon transfection into human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), we found no differences between ACH and ACH.p12I in virus production despite the absence of the p12I message in ACH.p12I-transfectants. Upon inoculation into rabbits, ACH- and ACH.p12I-transfectants both induced anti-HTLV-1 antibody responses, but those of ACH.p12I-inoculated rabbits were weaker. Furthermore, we were able to consistently isolate virus only from ACH-inoculated animals, indicating that HTLV-1 p12I is important for viral infectivity in vivo. These data provide the first evidence of a functional role of p12I in establishing persistent HTLV-1 infections and suggest a novel target for antiviral therapies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids and transfection of PBMC.

Normal uninfected human PBMC were obtained by leukophoresis as previously described.18 PBMC were maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum, 0.3 mg/mL L-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 10 U/mL rIL-2 (complete media). Before transfection, PBMC were stimulated with 2 μg/mL phytohemagglutinin-P (PHA-P) and cultured for 4 days. Cells were then transiently transfected by electroporation as previously described18 using 10 μg of either the HTLV-1 molecular clone ACH,19 ACH.p12I, a construct in which aPst I site corresponding to the splice acceptor for the coding exon of the p12I message has been deleted (Fig 1), or the pKS− vector (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) only. Transfected cells were then restimulated with 2 μg/mL PHA-P, seeded in 24-well plates, and maintained in complete RPMI, with media changes and expansion of cultures to 6-well plates as needed.

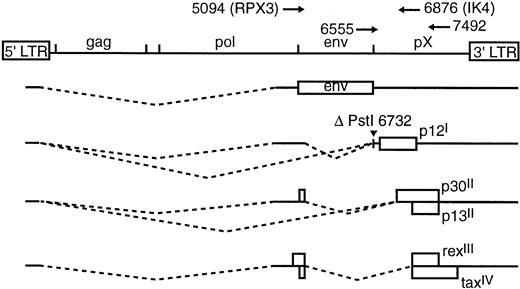

Schematic representation of spliced transcripts of HTLV-1. ORFs are represented by open boxes. Location of ΔPstI introduced in ACH.p12I is indicated and corresponds to the splice acceptor for exon 3 of the ORF I message. Primers used in PCR and RT-PCR are indicated above the full-length provirus. Numbers correspond to nucleotide positions with respect to the ACH clone.19

Schematic representation of spliced transcripts of HTLV-1. ORFs are represented by open boxes. Location of ΔPstI introduced in ACH.p12I is indicated and corresponds to the splice acceptor for exon 3 of the ORF I message. Primers used in PCR and RT-PCR are indicated above the full-length provirus. Numbers correspond to nucleotide positions with respect to the ACH clone.19

Detection of viral p19 matrix antigen.

As a comparison of virus production between ACH- and ACH.p12I-transfectants, culture supernatants were sampled weekly and assayed for p19 matrix antigen using a commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; Cellular Products, Buffalo, NY), with a detection sensitivity of 25 pg/mL p19 protein. Resultant absorbance values were compared with a standard curve generated in the same assay. Values were statistically compared by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA).

For detection of HTLV-1 p19 antigen ex vivo, rabbit PBMC were isolated from whole blood by density gradient (Lympholyte Rabbit; Cedarlane, Hornsby, Ontario, Canada), stimulated with 3 μg/mL Concanavalin A (Con A; Sigma, St Louis, MO) and cultured in complete RPMI. Culture supernatants were collected at day 7 and assayed for p19 antigen as described above.

Syncytia assay.

As an indirect measure of transfectant viral envelope production, a syncytia assay was performed as previously described.20 21Briefly, human PBMC transfectants were washed, resuspended at 5 × 105/mL, and duplicate aliquots placed into individual wells of a 96-well plate containing confluent human osteosarcoma (HOS) cells. After a 24-hour incubation, plates were washed, Wright's stained, and examined for syncytia containing at least four nuclei per cell. Data were expressed as the number of syncytia per well and values were statistically compared by ANOVA.

Infectivity assay.

Infectious virus production by transfectants was assayed by coculturing 1 × 106 naı̈ve rabbit PBMC with 1 × 105 gamma-irradiated (5,000 rad) transfectant cells in individual wells of a 24-well plate. Irradiated transfectants were also cultured alone to control for cessation of viral antigen production by irradiated cells. After maintenance in complete RPMI for 2 weeks, cells were washed to ensure measurement of de novo antigen production and cultured in fresh 24-well plates for 7 days, with aliquots of culture supernatant obtained at days 1 and 7 and assayed for p19 antigen as described above.

Detection of proviral sequences and viral mRNA.

For detection of provirus in transfectants or rabbit PBMC, genomic DNA was obtained by affinity column (QIAamp; Qiagen, Santa Clarita, CA) and examined for the presence of HTLV-1 nucleotide sequences by PCR. Five hundred nanograms of DNA was amplified using a primer pair specific for the HTLV-1 pX ORF I region (6555, 5′-AGGACCATGCATCCTCCGTCAG-3′; 7492, 5′-AGCCGATAACGCGTCCATCGAT-3′), which yielded a 938-bp product that included the Pst I deletion site of ACH.p12I at nucleotide 6732. As a positive control and to provide for semiquantitative comparison of HTLV-1 products, simultaneous amplification was performed with a primer pair specific for β-actin,15 which yielded a 415-bp product from rabbit DNA. After an initial 10-minute incubation at 95°C to activate the Taq polymerase (AmpliTaq Gold; Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, CA), 35 cycles of PCR were performed with the following cycle parameters: denaturation at 94°C for 1 minute, annealing at 55°C for 2 minutes, and extension at 72°C for 2 minutes, followed by a final extension at 72°C for 5 minutes. The amplified products were separated in a 1.5% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide. Each PCR reaction corresponded to the amount of DNA extracted from 5 × 105 cells. Titrations of HTLV-1-positive (MT-2) and -negative (Jurkat) cellular DNA were performed to determine sensitivity of the assay and detection of as little as 0.05 ng MT-2 DNA (50 cells) per 500 ng Jurkat DNA was achieved. We have previously determined that this MT-2 clone contains, on average, 2.1 proviral copies per cell (data not shown). Thus, we estimated the sensitivity of the PCR assay to be approximately 1 proviral copy per 5,000 cells. HTLV-1-specific products were confirmed by digestion with Pst I which, in the wild-type sequence, yielded fragments of 760 and 178 bp.

HTLV-1-specific PCR products were sequenced to further confirm specificity and ensure absence of second site mutations within ORF I/II. PCR reactions were purified (QIAquick; Qiagen) and sequenced by automated dye terminator cycle sequencing method (ABI Prism; ABI, Foster City, CA) using the primer pair 6555 and 7492, and an internal primer pair (6631, 5′-GAGTCATCCCTGTAAACCAAGC-3′; 7029, 5′-AGAGGAAGCGAAAAAAAGAGCG-3′).

For detection of the p12I message in transfected cells, total mRNA was obtained by affinity column technique (RNeasy; Qiagen) and reverse transcribed using Moloney murine leukemia virus (MMLV) RT (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN). Resulting cDNA was amplified as described above using the primer pair RPX3 and IK48 (corresponding to nucleotides 5094 and 6876, respectively), which spanned the second ORFI splice junction and thus yielded products of 1,783 bp (corresponding to unspliced gag-pol and singly spliced env transcripts) and 232 bp (corresponding to the doubly spliced ORFI transcript). Primers that amplified a 183-bp transcript of the ABL gene were used as a control for amplifiable RNA.22

Rabbit inoculation procedures.

To compare the relative infectivity of HTLV-1-transfected human PBMC, before inoculation we washed and plated 1 × 106 cells of each transfectant culture in 24-well plates and maintained them in complete RPMI for 72 hours. For inoculation we selected transfectants that produced equal amounts of virus based on the amount of HTLV-1 p19 protein in the 72-hour culture supernatants by antigen capture assay at the time of inoculation. Aliquots of all inocula were reserved for analysis of total viral antigen by Western blot as previously described,23 and mutation fidelity by PCR and RT-PCR as described above.

Twelve-week-old specific pathogen free New Zealand White rabbits (Hazelton, Kalamazoo, MI) were inoculated via the lateral ear vein with 1.0 × 107 gamma-irradiated (5,000 rad) cells previously transfected with ACH, ACH.p12I, or vector control (pKS−). Initially, two rabbits each were inoculated twice at 12 and 25 weeks of age with either ACH- (R31, 32) or ACH.p12I-transfected PBMC (R33, 34) to ensure infectivity of the inoculum. Subsequently, it was determined that a single inoculation was sufficient to cause infectivity and a second group of nine rabbits each were inoculated once at 12 weeks of age with either ACH- (R51-R54), ACH.p12I- (R55-R58), or pKS- (R50) transfected cells.

Serologic, clinical, and hematologic analysis.

Plasma antibody response to HTLV-1 in inoculated rabbits was determined by use of commercial ELISA (Vironostika HTLV-1 Microelisa System; Organon Technika, Durham, NC) that was adapted for use with rabbit plasma by substitution of alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:400 dilution) (Sigma). Plasma was diluted 1:12,800 (to obtain values in the linear range of the assay) and data expressed as absorbance values. Reactivity to specific viral antigenic determinants was detected using a commercial HTLV-1 Western blot assay (Cambridge Biotech, Worcester, MA) adapted for rabbit plasma by use of avidin-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:3,000 dilution) (Vector, Burlingame, CA). Plasma showing reactivity to Gag (p24 or p19) and Env (p21 or gp46) antigens was classified as positive for HTLV-1 seroreactivity.

Complete hematologic analysis was performed by automated cell counting (Coulter, Hialeah, FL) and differential enumeration of leukocytes and erythrocyte morphology in blood films. Body weights were monitored and rabbits were regularly evaluated for any overt signs of clinical disease. Rabbits were killed for necropsy and pathological examination at postinoculation intervals of 12 (R50-R58) or 26 (R31-R34) weeks.

RESULTS

In vitro analysis of ACH and ACH.p12I transfectants.

To construct the ACH.p12I clone, a Pst I site at ACH nucleotide 6732 corresponding to the splice acceptor for the last exon of the ORF I message was deleted (ΔPstI), resulting in abrogation of the message encoding p12I (Fig 1). To confirm that this message was not produced by ACH.p12I we transfected ACH and ACH.p12I into human PBMC and analyzed transfectant RNA by RT-PCR using primers RPX3 (5094) and IK4 (6876) (Fig 1). The expected 230-bp product corresponding to the p12I message was amplified from wild-type HTLV-1-infected cells but not ACH.p12I-transfectants (Fig 2A).

Effect of p12I mutation on RNA, protein, and infectious virus production in transfected PBMC. (A) RT-PCR of total RNA from ACH- and ACH.p12I-transfecants, MT-2 (HTLV-1-positive) and Jurkat (HTLV-1-negative) cells. The 232-bp p12I and constitutive 183-bp ABL transcript products are indicated. (B) p19 antigen detected by ELISA in ACH and ACH.p12I-transfectant PBMC culture supernatants. Results are expressed as mean pg/mL ± SEM of p19 antigen obtained from 10 independent transfections. (C) HTLV-1 env-mediated syncytia formation in HOS cells by ACH-, ACH.p12I-, or pKS- (vector control) transfectants, Jurkat (HTLV-1-negative), or HuT102 (HTLV-1-positive) cells. Results are expressed as mean number ± SEM of syncytia (four or more nuclei) per well obtained from 10 wells (five independent transfections); a, b, and c are significantly different, P < .05. Note that HuT102 is a high virus-producing cell line and is expected to induce higher numbers of syncytia compared to the PBMC transfectants. (D) Infectious virus production as measured by p19 antigen production from cultures containing lethally irradiated ACH- or ACH.p12I-transfectants alone or cocultured with naı̈ve rabbit PBMC. Results are expressed as absorbance values for 1 and 7 day after wash culture supernatants measured by p19 antigen ELISA.

Effect of p12I mutation on RNA, protein, and infectious virus production in transfected PBMC. (A) RT-PCR of total RNA from ACH- and ACH.p12I-transfecants, MT-2 (HTLV-1-positive) and Jurkat (HTLV-1-negative) cells. The 232-bp p12I and constitutive 183-bp ABL transcript products are indicated. (B) p19 antigen detected by ELISA in ACH and ACH.p12I-transfectant PBMC culture supernatants. Results are expressed as mean pg/mL ± SEM of p19 antigen obtained from 10 independent transfections. (C) HTLV-1 env-mediated syncytia formation in HOS cells by ACH-, ACH.p12I-, or pKS- (vector control) transfectants, Jurkat (HTLV-1-negative), or HuT102 (HTLV-1-positive) cells. Results are expressed as mean number ± SEM of syncytia (four or more nuclei) per well obtained from 10 wells (five independent transfections); a, b, and c are significantly different, P < .05. Note that HuT102 is a high virus-producing cell line and is expected to induce higher numbers of syncytia compared to the PBMC transfectants. (D) Infectious virus production as measured by p19 antigen production from cultures containing lethally irradiated ACH- or ACH.p12I-transfectants alone or cocultured with naı̈ve rabbit PBMC. Results are expressed as absorbance values for 1 and 7 day after wash culture supernatants measured by p19 antigen ELISA.

We then compared the mutant molecular clone ACH.p12I to that of wild-type ACH for the ability to produce virus by measuring the production of viral p19 matrix in transfectant culture supernatants by ELISA (Fig 2B). No significant differences were seen in cell numbers or amounts of p19 produced between ACH- or ACH.p12I-transfectants, indicating that abrogation of the ORF I message has no effect on viral core antigen production in vitro.

The ΔPstI overlaps the env message in the noncoding region after the env termination codon. To ensure that viral envelope expression was not affected by the ΔPstI, we measured envelope expression by monitoring syncytia induction in HOS indicator cells after coculture with transfected human PBMC. Coculture of HOS cells results in syncytia formation and is dependent on expression of viral envelope.21 No significant differences were seen in numbers of syncytia induced in HOS cells by ACH- and ACH.p12I-transfectants (Fig 2C).

To compare the in vitro infectivity of the wild-type and mutant clones in rabbit primary cells, we cocultured lethally irradiated transfectants with naı̈ve, activated rabbit PBMC. Viral p19 antigen was produced in similar amounts by all ACH- and ACH.p12I-transfectant cocultures, but not in cultures containing irradiated transfectants alone, suggesting that abrogation of p12I has no effect on the ability of HTLV-1 to infect rabbit PBMC in vitro (Fig 2D).

In vivo analysis of ACH and ACH.p12I transfectants.

To determine if abrogation of p12 affected the ability of HTLV-1 to infect and replicate in rabbits, we inoculated six rabbits each with ACH- or ACH.p12I-transfected, lethally irradiated human PBMC. Before inoculation, there was no difference in the amount of soluble p19 or cell-associated viral antigen produced by transfectants, as measured by ELISA or Western blot analysis, respectively (data not shown).

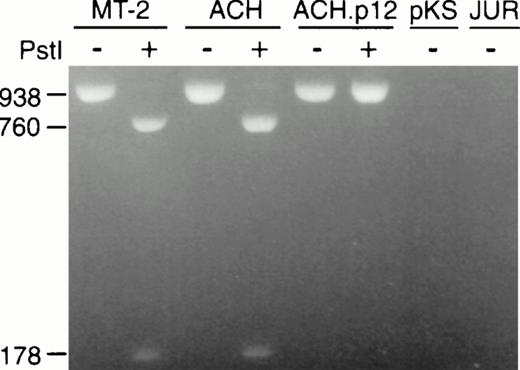

To ensure that the ΔPstI was conserved in ACH.p12I-transfectants at the time of inoculation, we analyzed the HTLV-1 ORF I/II region in samples of the inocula. A 938-bp region containing the mutation site was amplified from transfectants using the 6555/7492 primer pair and then digested with Pst I. As expected, Pst I digestion of DNA amplified from ACH-transfectants yielded fragments of 760 and 178 bp, in contrast to that of ACH.p12I, which did not digest, since the construction of the clone destroys the Pst I site coinciding with ORF I splice acceptor (Fig 3). To confirm these findings and to ensure that there were no second site mutations within ORFs I or II, we sequenced the PCR products, which include all of ORF I/II. Except for the expected ΔPstI mutation, no sequence differences were noted in ORFs I and II between the ACH- and ACH.p12I-transfectants (data not shown).

Conservation of ΔPstI mutation in ACH.p12I-transfectants at time of inoculation shown by PCR amplification of genomic DNA from ACH-, ACH.p12I-, and pKS- (vector control) transfected PBMC, MT-2 (HTLV-1-positive), and Jurkat (HTLV-1-negative) cells. The native (−) or Pst I-digested (+) 938 bp HTLV-1 ORF I/II-specific product is present in HTLV-1-positive cells and lacks the Pst I site corresponding to the ORF I exon 3 splice acceptor site in ACH.p12I-transfectants.

Conservation of ΔPstI mutation in ACH.p12I-transfectants at time of inoculation shown by PCR amplification of genomic DNA from ACH-, ACH.p12I-, and pKS- (vector control) transfected PBMC, MT-2 (HTLV-1-positive), and Jurkat (HTLV-1-negative) cells. The native (−) or Pst I-digested (+) 938 bp HTLV-1 ORF I/II-specific product is present in HTLV-1-positive cells and lacks the Pst I site corresponding to the ORF I exon 3 splice acceptor site in ACH.p12I-transfectants.

To determine serologic response of rabbits to inoculated transfectants, we measured anti-HTLV-1 antibody levels in rabbit plasma by ELISA. Reactivity to specific HTLV-1 antigens was subsequently confirmed at all time points by Western blot analysis. Data representing all observed patterns of seroconversion are shown (Fig 4). As expected after using infected cellular inocula, seroconversion was detected in all rabbits as indicated by rising antibody titers over the course of the experiment. However, antibody titers were higher in ACH-inoculated rabbits (R51-55) or rabbits receiving two inocula of either clone (R31-34) than in rabbits receiving one inoculation of pKS- (R50) or ACH.p12I- (R55-58) transfected cells (Fig 4A). The intensity of Western blot reactivity correlated with ELISA titers and all ACH- and ACH.p12I-inoculated rabbits were considered seropositive for HTLV-1 (reactivity to gag and env antigens), although rabbits inoculated once with ACH.p12I generally exhibited weaker reactivity to a smaller number of HTLV-1 antigenic determinants (Fig 4B).

HTLV-1-specific serologic response in rabbits inoculated with transfected PBMC. Represented are rabbits inoculated once (R50, 53, 57, and 58) or twice (R32 and 33) with ACH- (R53 and 32), ACH.p12- (R57, 58, and 33), or pKS (vector control)- (R50) transfectants. Data shown are absorbance values of plasma samples diluted 1:12,800 and measured by anti-HTLV-1 antibody ELISA (A) or reactivity to specific HTLV-1 antigenic determinants measured by Western blot analysis (B). Note that reactivity of R50 (negative control) on ELISA is nonspecific for HTLV-1 as shown by Western blot analysis and is attributable to cross reactivity of cellular antigens in the inoculum and the ELISA. The data shown for each rabbit are representative of the larger inoculation group. Thus, R32 and R33 represent two rabbits each, R53 represents four rabbits, and R57 and R58 demonstrate two different reaction patterns seen among the four rabbits comprising that inoculant group.

HTLV-1-specific serologic response in rabbits inoculated with transfected PBMC. Represented are rabbits inoculated once (R50, 53, 57, and 58) or twice (R32 and 33) with ACH- (R53 and 32), ACH.p12- (R57, 58, and 33), or pKS (vector control)- (R50) transfectants. Data shown are absorbance values of plasma samples diluted 1:12,800 and measured by anti-HTLV-1 antibody ELISA (A) or reactivity to specific HTLV-1 antigenic determinants measured by Western blot analysis (B). Note that reactivity of R50 (negative control) on ELISA is nonspecific for HTLV-1 as shown by Western blot analysis and is attributable to cross reactivity of cellular antigens in the inoculum and the ELISA. The data shown for each rabbit are representative of the larger inoculation group. Thus, R32 and R33 represent two rabbits each, R53 represents four rabbits, and R57 and R58 demonstrate two different reaction patterns seen among the four rabbits comprising that inoculant group.

To determine the HTLV-1-infected status of inoculated rabbits, we measured soluble p19 antigen in ex vivo PBMC culture supernatants (Table 1). Viral antigen was detected in cultures from all ACH-inoculated rabbits by 6 weeks postinoculation. However, we were unable to detect any p19 production in PBMC cultures derived from ACH.p12I-inoculated rabbits at any time point.

Viral Detection in PBMC of Rabbits Inoculated With Transfected Cells

| Transfectant . | Rabbit (no. inoc.)-150 . | Test-151 . | No. Rabbits Positive/No. Monitored at Indicated Week Postinoculation . | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 . | 1 . | 2 . | 4 . | 6 . | 8 . | 10 . | 12 . | 16 . | 20 . | 26 . | |||

| ACH | 31, 32 (2) | p19 | 0/2 | ND | 0/2 | 1/2 | 2/2 | 2/2 | 2/2 | 2/2 | 2/2 | 2/2 | 2/2 |

| PCR | 0/4 | ND | 0/2 | 1/2 | 2/2 | 2/2 | 2/2 | 2/2 | 1/2 | 2/2 | 2/2 | ||

| 51-54 (1) | p19 | 0/4 | 1/4 | 2/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 | —-153 | — | — | |

| PCR | 0/4 | 1/4-152 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 | — | — | — | ||

| ACH.p12 | 33, 34 (2) | p19 | 0/2 | ND | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 |

| PCR | 0/6 | ND | 0/2 | 0/2 | 2/2-152 | 1/2-152 | 2/2-152 | 2/2-152 | 1/2-152 | 0/2 | 0/2 | ||

| 55-58 (1) | p19 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | — | — | — | |

| PCR | 0/4 | 0/4 | 2/4-152 | 1/4-152 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | — | — | — | ||

| pKS | 50 (1) | p19 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | — | — | — |

| PCR | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | — | — | — | ||

| Transfectant . | Rabbit (no. inoc.)-150 . | Test-151 . | No. Rabbits Positive/No. Monitored at Indicated Week Postinoculation . | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 . | 1 . | 2 . | 4 . | 6 . | 8 . | 10 . | 12 . | 16 . | 20 . | 26 . | |||

| ACH | 31, 32 (2) | p19 | 0/2 | ND | 0/2 | 1/2 | 2/2 | 2/2 | 2/2 | 2/2 | 2/2 | 2/2 | 2/2 |

| PCR | 0/4 | ND | 0/2 | 1/2 | 2/2 | 2/2 | 2/2 | 2/2 | 1/2 | 2/2 | 2/2 | ||

| 51-54 (1) | p19 | 0/4 | 1/4 | 2/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 | —-153 | — | — | |

| PCR | 0/4 | 1/4-152 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 | — | — | — | ||

| ACH.p12 | 33, 34 (2) | p19 | 0/2 | ND | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 |

| PCR | 0/6 | ND | 0/2 | 0/2 | 2/2-152 | 1/2-152 | 2/2-152 | 2/2-152 | 1/2-152 | 0/2 | 0/2 | ||

| 55-58 (1) | p19 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | — | — | — | |

| PCR | 0/4 | 0/4 | 2/4-152 | 1/4-152 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | — | — | — | ||

| pKS | 50 (1) | p19 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | — | — | — |

| PCR | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | — | — | — | ||

Abbreviation: ND, not determined.

Rabbits were inoculated once (R50-58) or twice (R31-34) with indicated transfectant.

p19, ELISA measurement of p19 antigen in 7-day supernatants of ex vivo PBMC cultures, positive indicates concentrations of at least 15 pg/mL; PCR, amplification of HTLV-1 ORF I/II–specific proviral sequence from rabbit PBMC. PCR sensitivity was estimated to be 1 proviral genome per 5,000 cells.

Faint positives.

Rabbits 50-58 were killed at 12 weeks (termination of study).

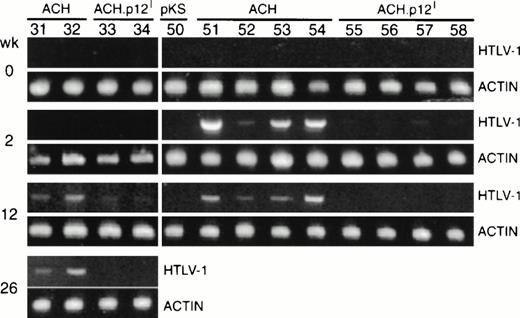

As a further means of detecting infection in rabbits, we attempted to amplify HTLV-1-specific proviral sequences from rabbit PBMC DNA by PCR. Provirus was detected in all ACH-inoculated rabbits by 6 weeks postinoculation (Table 1). In general, in ACH-inoculated rabbits, HTLV-1-specific bands in comparison to β-actin-specific bands were faint or undetectable at weeks 1 and 2 and reached maximum intensity at 4 to 6 weeks, suggesting that recovery of provirus from these animals was the result of replicating virus and not residual inoculum (Fig 5). In contrast to the strong positive reactions in all ACH-inoculated animals, we were unable to consistently amplify proviral sequences from ACH.p12I-inoculated rabbits, and when a positive reaction occurred the signal was very weak. No ACH.p12-inoculated rabbits were positive for proviral sequences at the termination of the study (Fig 5 and Table 1). These data together with failure to detect antigen and weak serologic responses in ACH.p12I-inoculated rabbits strongly suggest that selective abrogation of p12I significantly interferes with the ability of HTLV-1 to establish persistent infection in vivo.

Detection of HTLV-1 proviral sequences in rabbits inoculated with transfected PBMC. Genomic DNA from PBMC of rabbits inoculated with ACH-(R51-54 and 31-32), ACH.p12- (R55-58 and 33-34), or pKS (vector control)- (R50) transfectants was amplified by PCR using primers specific for HTLV-1 pX (938 bp) or β-actin (415 bp). Sensitivity of the PCR was estimated to be 1 proviral genome per 5,000 cells.

Detection of HTLV-1 proviral sequences in rabbits inoculated with transfected PBMC. Genomic DNA from PBMC of rabbits inoculated with ACH-(R51-54 and 31-32), ACH.p12- (R55-58 and 33-34), or pKS (vector control)- (R50) transfectants was amplified by PCR using primers specific for HTLV-1 pX (938 bp) or β-actin (415 bp). Sensitivity of the PCR was estimated to be 1 proviral genome per 5,000 cells.

DISCUSSION

HTLV-1 p12I is a conserved 99-amino acid protein encoded by an ORF located between the env and tax/rex genes.6-8 To date the role of p12I in HTLV-1 replication has not been identified, although in vitro overexpression of the protein suggests interesting protein-protein interactions potentially affecting cellular signal transduction or membrane receptor expression.7,8 10Our findings indicate that abrogation of the p12I message does not result in loss of viral infectivity. The destruction of the ORF I splice acceptor site resulted in loss of expression of the p12I message but had no effect on the ability of the transfected virus to produce Gag or Env proteins, as measured by p19 ELISA and syncytia induction, respectively. Furthermore, we confirmed that p12I-mutant virus is fully competent in the production of infectious virus and that, like wild-type HTLV-1, this virus is infectious in rabbit PBMC in vitro.

The ability of HTLV-1 to establish a persistent asymptomatic infection in rabbits typical of the large majority of infected human beings is well established.24 We and others have used rabbits as an animal model of HTLV-1 infection to study viral transmission and test potential vaccines.20 25-28 Here we used the rabbit model to test the possibility that the effects of p12I ablation would be manifested in vivo. At the time of inoculation into rabbits, there were no differences in either cell number or amount of replicating virus between ACH- and ACH.p12I-infected PBMC inocula. The successful inoculation of these cells was confirmed by the early seroconversion to HTLV-1 of all rabbits, with the exception of the rabbit inoculated with pKS vector only. As in our previous studies, ACH-transfected cells induced a vigorous and sustained humoral response in rabbits against all major viral antigenic determinants. In contrast, rabbits inoculated once with ACH.p12I exhibited a relatively weaker humoral immune response. This was likely due to the decreased or absent viral infectivity of the ACH.p12Imutant compared with that of wild-type virus and is supported by our inability to recover virus from ACH.p12I-inoculated rabbits. The vigorous immune response noted in rabbits inoculated twice with ACH.p12I can be attributed to the amnestic response elicited by the second inoculation because, as in the other ACH.p12I-inoculated rabbits, we failed to detect persistent infection in these animals.

In asymptomatic HTLV-1-infected humans and rabbits, levels of viral transcription are typically very low.26,29 Upon mitogenic activation of infected PBMC ex vivo, however, viral replication can be efficiently induced.1 25 We were able to detect viral p19 antigen in 7-day PBMC cultures by 4 weeks in all ACH-inoculated rabbits. The absence of p19 antigen in most cultures from 1 and 2 weeks postinoculation reflects the in vivo lag period of viral replication and suggests that p19 antigen production was derived from newly infected rabbit PBMC and not residual inoculum. Our inability to detect p19 antigen from ACH.p12I-inoculated rabbits at any time point suggests that viral replication was absent or depressed in relation to wild-type virus.

In support of our previous findings that ACH is consistently infectious in rabbits, we had no difficulty in amplifying HTLV-1-specific sequences from ACH-inoculated rabbits.17 As we noted with ex vivo p19 antigen production, there was a period of 1 to 4 weeks in these rabbits when we could not detect provirus by PCR, reflecting the lag phase of viral replication. In contrast to ACH-inoculated animals, we inconsistently detected provirus in ACH.p12I-inoculated rabbits. Although occasional positive reactions were noted in these animals, they were faint and at the lower limit of our assay sensitivity, suggesting that proviral loads were much lower in rabbits inoculated with the mutant clone. Furthermore, positive reactions from ACH.p12I-inoculated rabbits were not consistent from week to week, and all these rabbits were negative by the end of the study. Although we cannot rule out that ACH.p12I-inoculated rabbits were persistently infected with viral loads that were below our limits of detection or that there exists in these rabbits a reservoir of virus in an uninvestigated tissue or organ, our in vivo findings provide strong evidence that HTLV-1 p12I is critical for optimal viral infectivity and in maintaining the persistent characteristic of the human infection.

Because we cultured transfected cells for 2 weeks before inoculation into rabbits it was necessary for us examine the state of the ΔPstI mutation immediately before introduction of the cells into rabbits. If the loss of p12I had an undetected, deleterious effect on viral replication in vitro, there would be strong selective pressure for rescue or reversion. However, no changes in the sequence of ORFs I or II from that of wild type were detected in our inocula, and the ΔPstI mutation was preserved. The absence of any deleterious phenotype in vitro makes the likelihood very small that mutations arose during the culture period in other genes required for viral replication. Furthermore, if in vivo mutation of other viral genes were to account for the observed phenotype, these would have had to occur independently against strong selective pressure in all six ACH.p12I-inoculated rabbits but in none of the ACH-inoculated animals. Thus, although this possibility cannot be completely ruled out, we consider it extremely unlikely.

Ours is the first study to show a functional role for p12Iin viral replication or infectivity. It is not suprising that the functionality of this gene is only evident in vivo, as there are numerous examples of viral genes that are required only for efficient replication or pathogenesis in vivo, including simian immunodeficiency virus nef and herpes simplex virus 1 γI34.5.30,31 The mechanism of the in vivo functionality of p12I will require further studies to elucidate. Because p12I has been shown to interact with the IL-2Rβ and γ chains, it may be speculated that modulation of the IL-2 signaling pathway of HTLV-1-infected T cells by p12Icould enhance the transcriptional activity of the virus and promote replication.13,32,33 This effect, while potentially very important for viral transmission in vivo, may be masked by the broad activation state of transformed or mitogen and IL-2-treated primary cells used in in vitro studies. Interactions of p12I with other viral gene products may be important as well. Recently it has been shown that proteins encoded by alternatively spliced mRNAs inhibit the function of HTLV-2 Rex.34 Alternatively, p12I may function to mask immune recognition of infected cells through the downmodulation of cell-surface molecules such as major histocompatibility complex gene products. Although this association has not been shown, it is interesting to note that a recent report suggests that p12I associates with immature forms of IL2R-β and γ chains, retaining them in the Golgi apparatus and resulting in decreased cell-surface expression.13Finally, it is important to note that our results do not rule out a role of the untranslated p12I mRNA (eg, regulation of RNA splicing) in the ability of the virus to establish an infection in vivo.

HTLV-1 is a significant worldwide health problem and is known to cause an aggressive T-cell malignancy.1 The identification and characterization of p12I and other viral regulatory proteins besides Tax and Rex will shed light on the mechanisms of HTLV-1 replication and pathogenesis, as well as potential insight into general mechanisms of oncogenesis. Furthermore, abrogation of p12I may be an efficacious means of generating an attenuated live-virus vaccine. Further studies will be necessary to examine the plausibility of this idea and to elucidate the roles that p12I plays in the life cycle of HTLV-1.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Jason Kimata and Fen-Hwa Wong for construction of the plasmids, Michael Robek for PCR primer design and helpful discussions, Patrick Green and Gary Kociba for critical reading of the manuscript, and Tim Vojt for preparation of figures.

Supported by National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute Grants No. CA-55185 (M.D.L.), P30CA16058 (OSU Cancer Center core grant) and CA-63417 (M.D.L. subcontract from L.R.), and by National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease Grant No. AI 01474 (M.D.L.) and the Glen Barber Fund (N.D.C.).

Address reprint requests to Michael D. Lairmore, DVM, PhD, Department of Veterinary Biosciences, The Ohio State University, 1925 Coffey Rd, Columbus, OH 43210-1093.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked "advertisement" is accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal