Abstract

The recently-identified Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein gene (WASP) is responsible for the Wiskott-Aldrich X-linked immunodeficiency as well as for isolated X-linked thrombocytopenia (XLT). To characterize the regulatory sequences of the WASP gene, we have isolated, sequenced and functionally analyzed a 1.6-Kb DNA fragment upstream of the WASP coding sequence. Transfection experiments showed that this fragment is capable of directing efficient expression of the reporter chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) gene in all human hematopoietic cell lines tested. Progressive 5′ deletions showed that the minimal sequence required for hematopoietic-specific expression consists of 137 bp upstream of the transcription start site. This contains potential binding sites for several hematopoietic transcription factors and, in particular, two Ets-1 consensus that proved able to specifically bind to proteins present in nuclear extracts of Jurkat cells. Overexpression of Ets-1 in HeLa resulted in transactivation of the CAT reporter gene under the control of WASP regulatory sequences. Disruption of the Ets-binding sequences by side-directed mutagenesis abolished CAT expression in Jurkat cells, indicating that transcription factors of the Ets family play a key role in the control of WASP transcription.

THE WISKOTT-ALDRICH syndrome (WAS) is a severe X-linked condition characterized by immunodeficiency, thrombocytopenia, eczema and a highly increased risk of hematopoietic tumors, in particular non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. The gene responsible for this syndrome (termed WASP, for Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein) has been identified by positional mapping,1,2 and a number of different mutations within its coding sequence have been detected in patients with WAS and the cognate syndrome, X-linked isolated thrombocytopenia (XLT).3-5 The WASP gene encodes a 502 amino acid–long protein, extremely rich in prolines, that has been implicated in the control of cytoskeletal organization6,7as well as in signal transduction processes.8 9

The WASP gene expression appears to be subjected to a developmental, tissue-specific and lineage-specific control. High levels of WASP mRNA are observed in fetal lymphoid organs, lymphocytes, and macrophages from the peripheral blood of adults, as well as in lymphoid and megakaryoblastic cell lines.1 This is likely to reflect the presence of regulatory regions within the gene that ensure tissue specificity. The characterization of the cis-acting sequences that govern WASP expression is essential not only for understanding the molecular mechanisms of its specificity, but also for reasons related to diagnostic and therapeutic issues: (1) The identification of WASP makes gene replacement a potentially feasible approach for the treatment of the Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome; however, a prerequisite for gene therapy is the availability of vectors capable of ensuring an expression profile as close as possible to that of the endogenous gene; and (2) so far, a diversity of mutations in the coding sequence or at splice sites within the WASP gene have been found in most of the patients analyzed; however, it is conceivable that also mutations occurring in regulatory sequences may impair WASP expression thereby giving rise to the disease; furthermore, cases of WASP-like syndromes have been reported, in which both family history as well as molecular data ruled out the involvement of the X chromosome and suggested autosomal inheritance.10 Thus, it is possible that molecular defects affecting the structure and/or the abundance of transcription factors, which are crucial for WASP gene expression, may be involved in the pathogenesis of these syndromes. For these reasons we have set out to study the mechanisms and molecules that control WASP gene expression. In this report, we discuss the characterization of the regulatory sequence of the WASP gene and the identification of two Ets-binding sites within this region that are indispensable for tissue-specific expression in human hematopoietic cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Identification of the WASP transcription initiation point.

To identify the transcription start site of the WASP gene, because no obvious TATA consensus sequence was detected in the 5′ flanking region, the polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based method of 5′ RACE11 was used (5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends [RACE] kit, Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD). Briefly, Jurkat RNA was subjected to reverse transcription by using the oligonucleotide WASP REV 1, complementary to the WASP transcript (nucleotide [nt] 668 to 647: 5′-ATCGTGAACTCGTGATGTCAGG-3′). A dC tail was added to the cDNA thus synthesized, and PCR was performed by using an oligo(dG)-containing primer and a second, nested primer complementary to WASP mRNA (WASP REV 2: 5′-GCCCCGCTTGGCAGTCATT-3′; nt 423 to 405). The PCR product was inserted into the vector pGEM-T Easy Vector (Promega, Madison, WI) and its sequence was determined, showing that the 5′ end of the PCR product extended 13 nt further than the cDNA originally reported by Derry et al.1

Isolation of the 5′ flanking region of WASP and preparation of WASP-chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) constructs.

An arrayed cosmid library of the chromosome X was screened by using a probe obtained by PCR that spans the first exon and part of the first intron of the WASP gene (nt 1-222). Twenty cosmids hybridizing to this probe were isolated. Digestion with the restriction enzyme,Pst I (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA), yielded a DNA fragment of approximately 2 Kb containing part of the first intron, the entire first exon, and a region of 1,580 bp upstream of the latter. This fragment was inserted into the Bluescript II KS plasmid (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and sequenced. The presence of a uniqueBbs I restriction site located in the 5′ untranslated region allowed removal of the WASP coding sequence. WASP-CAT plasmids were constructed by insertion of different fragments of the WASP 5′ flanking sequence, obtained by digestion with suitable restriction enzymes (−1,580/+33, −1,167/+33, −988/+33, −829/+33, −365/+33, and −137/+33) in front of the bacterial CAT gene in the vector PBL-CAT3.12

The SVETS-1 expression vector, carrying the Ets-1 cDNA driven by the SV40 promoter13 was kindly provided by Dr N. Taniguchi (University of Osaka, Osaka, Japan).

Cell cultures, transfections, and luciferase and CAT assays.

All hematopoietic cell lines were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (ICN Pharmaceuticals Inc, Costa Mesa, CA) containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; Hyclone, Logan, UT), 100 U/mL of penicillin, 100 μg/mL of streptomycin, and 2 mmol/L glutamine (ICN). The nonhematopoietic cell lines HeLa, Hep 3B and CaCo-2 were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; ICN), supplemented as above.

Transfections were performed by electroporation with a GenePulser apparatus (Biorad, Hercules, CA). Briefly, 5 × 106cells were resuspended in 300 μL of RPMI 20% FCS containing 15 μg of the relevant WASP-CAT plasmid and 3 μg of pGL2 (Promega, Madison, WI), a luciferase plasmid used as an internal control, and then subjected to one pulse of 250 V, 960 μFd (Jurkat), or two pulses of 200 mV, 960 μFd (all other cell lines). The cells were then diluted into RPMI 10% FCS and cultured for 48 hours before preparation of cell extracts for luciferase and CAT assays.14

Nuclear extracts.

Nuclear extracts were prepared as described16 from 2 × 107 cells by pellet homogenization in 2 volumes of 10 mmol/L HEPES, pH 7.9, 10 mmol/L KCl, 1.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 1 mmol/L EDTA, 0.5 mmol/L phenylmethyl sulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), and 10% glycerol. Nuclei were centrifuged at 1,000g for 5 minutes, washed, and resuspended in 2 volumes of the above solution. KCl (3 mol/L) was added to a final concentration of 0.39 mol/L KCl. Nuclei were extracted at 4°C for 1 hour and centrifugation at 10,000g for 30 minutes. The supernatants were clarified by centrifugation and stored in aliquots at −80°C. Protein concentration was determined with the Bradford method17(Biorad, Hercules, CA).

DNA probes and electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA).

The following oligonucleotides were used (coding strand is reported; mutations are indicated in lower case): W-EtsP 5′-GCTGCTCATTGCGGAAGTTCCT-3′; W-ΔEtsP 5′-GCTGCTCATTGCGagAGTTCCT-3′; W-EtsD 5′-TTGCATTTCCTGTTCCCTTGCTGC-3′; W-ΔEtsD 5′-TTGCATTctCTGTctCCTTGCTGC-3′; Ets-1185′-GATCTGCGCGCTTCCGCTCTCCGAGGATC-3′; Ets-1 Mut18 5′-GATCTGCGCGCTTggcgTCTCCGAGGATC-3′. EMSAs were performed as described.19 20Briefly, double-stranded oligonucleotides were end-labeled with γ-32P-ATP (Amersham International, Milan, Italy) by using polynucleotide kinase (Promega, Madison WI). A total of 2 × 104 cpm of each oligonucleotide were incubated at room temperature for 20 minutes with 5 μg of nuclear extract in the presence of 3 μg of poly (dI-dC), in 20 μL of a buffer consisting of 10 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 50 mmol/L NaCl, 1 mmol/L EDTA, 1 mmol/L DTT, and 5% glycerol. Protein DNA complexes were separated from free probe on a 5.5% polyacrylamide gel run in 0.25× Tris borate buffer at 200 V for 3 hours at room temperature. The gels were dried and exposed to radiograph film (Kodak AR, Rochester, NY). For competitions, a 50-fold molar excess of unlabeled competitor oligonucleotide was incubated with the nuclear extract for 10 minutes at room temperature before addition of the labeled oligonucleotide.

Site-directed mutagenesis.

To disrupt the Ets sites in the −137/+33 fragment, site-directed mutagenesis was performed by PCR with the following primers: Bluescript MCS FWD: 5′-CTCGAGGTCGACGGTATCGATA-3′; Bluescript MCS REV: 5′-CGACTCACTATAGGGCGAATTGG-3′; W-ΔEtsP FWD 5′-GCTGCTCATTGCGAGAGTTCCT-3′; W-ΔEtsP REV 5′-AGGAACTCTCGCAATGAGCAGC-3′; W-ΔEtsD FWD 5′-TTGCATTCTCTGTCTCCTTGCTGC-3′; W-ΔEtsD REV 5′-GCAGCAAGGAGACAGAGAATGCAA-3′.

Briefly, to obtain single mutants, two rounds of PCR were performed, using as a template a Bluescript KS plasmid carrying the W-137/+33 in the HindIII-5′→3′-XbaI orientation. In the first round, PCR reactions were performed by using the following combinations of amplimers: (1) Bluescript MCS FWD + W-ΔEtsP REV; (2) Bluescript MCS FWD + W-ΔEtsD REV; (3) W-ΔEtsP FWD + Bluescript MCS REV; and (4) W-ΔEtsD FWD + Bluescript MCS REV.

The PCR products thus obtained were purified from agarose gels and used as templates in the second round of PCR, in which the two fragments carrying the proximal or distal Ets site mutation were denatured, allowed to anneal through the overlapping sequence, and amplified in the presence of the Bluescript MCS FWD and Bluescript MCS REV primers. The resulting PCR products were digested with HindIII andXba I inserted into Bluescript, sequenced to confirm the fidelity of amplification, and subcloned into PBL-CAT3. The double mutant, W-ΔEtsP/ΔEtsD, was generated with the same strategy by using the single mutant Bluescript W-ΔEtsD as a template and amplifying with the W-ΔEtsP and the Bluescript MCS primers.

RESULTS

Determination of the sequence of the 5′ flanking region of the WASP gene and identification of the transcription initiation site.

A fragment of genomic DNA spanning approximately 1,600 bp upstream of the WASP coding sequence was isolated from a cosmid library of chromosome X and sequenced. The nucleotide sequence data of the entire fragment will appear in the EMBL, GenBank, and DDBJ Nucleotide Sequence Databases under the accession number Y16094. In agreement with the data of Derry et al21 on 500 bp of the 5′ flanking sequence, no obvious TATA box or GC-rich islands were found in the region close to the coding sequence. To address the question whether an additional 5′ exon(s) may exist, we attempted to map the WASP transcription start site by the PCR-based technique, 5′ RACE. One major band was amplified, in which the 5′ end extended 13 nucleotides upstream of the first nucleotide of the longest WASP cDNA previously identified.1 This start position will be henceforth referred to as +1. The presence of an AC at the transcription initiation point, surrounded by a stretch of pyrimidines, is reminiscent of the initiator motif observed in the adenovirus major-late promoter.22

Identification and dissection of the regulatory sequence in the 5′ flanking sequence of the WASP gene, which confers hematopoietic-specific expression.

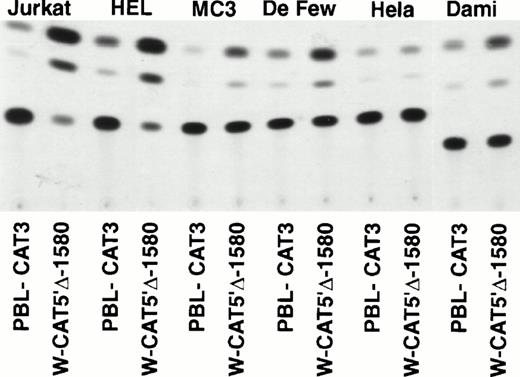

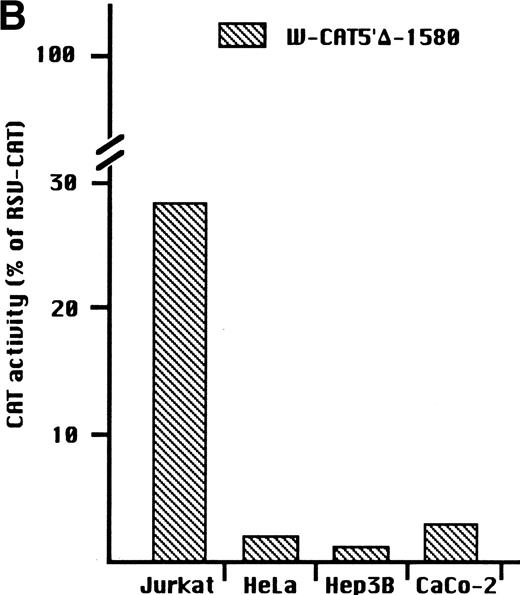

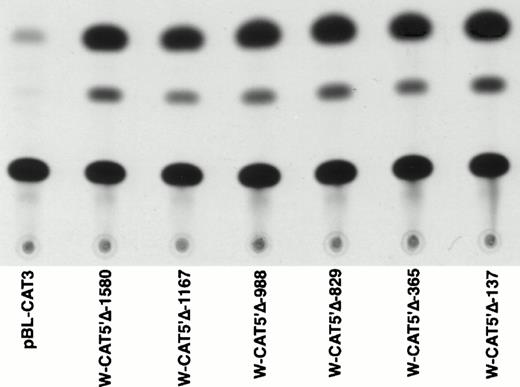

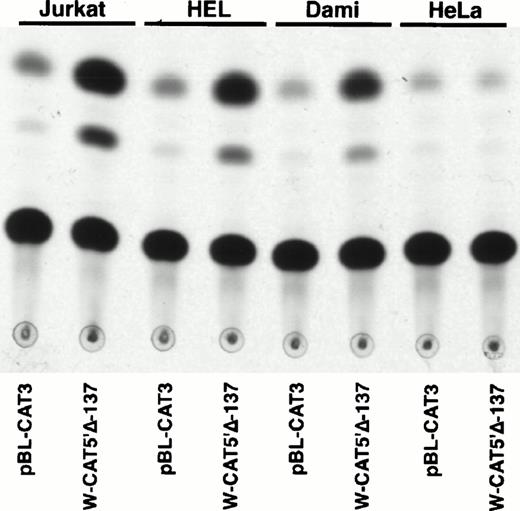

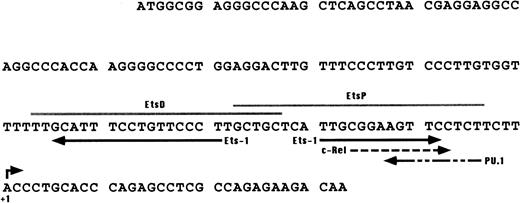

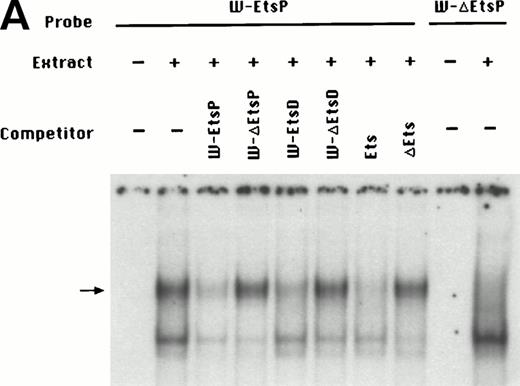

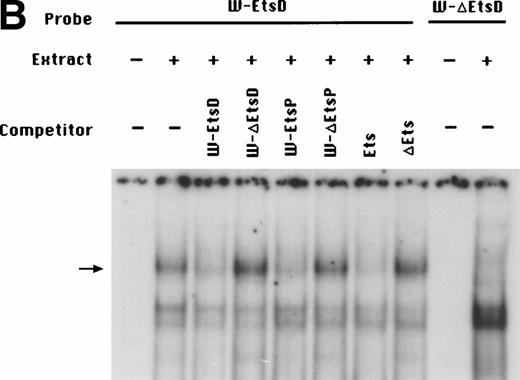

To identify the minimal WASP promoter, we constructed a series of plasmids in which different fragments of the WASP 5′ flanking region were inserted upstream of the CAT reporter gene and assayed their expression in a variety of hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic cell lines. Initial experiments showed that a fragment of approximately 1.6 Kb of the WASP 5′ flanking region (W-CAT5′Δ-1,580) was sufficient to ensure CAT expression in human hematopoietic cell lines including Jurkat (T-lymphoid), De Few and MC3 (B-lymphoblastoid), HEL (erythroid/megakaryoblastic), and Dami (megakaryoblastic; Fig 1A) but not in cell lines derived from cervical carcinoma (HeLa), hepatocarcinoma (Hep 3B), or colon carcinoma (CaCo-2; Fig 1B). Primer extension confirmed that the transcription start site of the CAT mRNA was in the expected region (not shown). Progressive 5′ deletions of the −1,580/+33 fragment were obtained exploiting the presence of unique restriction sites and inserted upstream of the CAT gene. Transfection experiments showed that the fragment −137/+33 was still able to direct strong, specific CAT expression in human hematopoietic cell lines (Fig 2A and B). Analysis of this sequence (Fig 3) highlighted the presence in the region −20/−5 of a cluster of three potential binding sites, partially overlapping, for the hematopoietic transcription factors Ets-1, c-Rel, and PU.1, respectively. An additional Ets-1 consensus (henceforth referred to as distal) is located between nt −30 and −45. The ability of the putative Ets-binding sequences to interact with the corresponding nuclear factors was investigated by EMSA by using two oligonucleotides spanning the region between nt −47 and −5 of the WASP promoter (designated W-EtsP and W-EtsD). As shown in Fig 4A and B, both the proximal and the distal Ets motifs could bind to (lanes 1-3) and cross-compete for (lane 5) a factor(s) present in the nuclear extracts of Jurkat (Fig 4) and HEL cells (not shown). An oligonucleotide carrying the “canonical” wild-type, but not the mutant, Ets-1 consensus effectively competed for binding with both W-EtsP and W-EtsD (lane 7-8). As expected, a nuclear factor binding specifically to the PU.1 site and recognized by an anti-PU.1 antibody was instead expressed in HEL but not in Jurkat cells, (results not shown).

(A) Expression of the W-CAT5′▵-1,580 construct in human hematopoietic cell lines. Transfections and CAT assays were performed as indicated in Materials and Methods. The amounts of extracts used in CAT assays were normalized based on the values of luciferase activity. PBL3-CAT was used as a negative control. (B) Comparison of the expression of W-CAT5′▵-1,580 in Jurkat cells and nonhematopoietic human cell lines. CAT activity is expressed as a percentage of the values obtained with the strong universal CAT vector, RSV-CAT, in each cell line.

(A) Expression of the W-CAT5′▵-1,580 construct in human hematopoietic cell lines. Transfections and CAT assays were performed as indicated in Materials and Methods. The amounts of extracts used in CAT assays were normalized based on the values of luciferase activity. PBL3-CAT was used as a negative control. (B) Comparison of the expression of W-CAT5′▵-1,580 in Jurkat cells and nonhematopoietic human cell lines. CAT activity is expressed as a percentage of the values obtained with the strong universal CAT vector, RSV-CAT, in each cell line.

Expression of CAT constructs carrying progressive 5′ deletion mutants of the flanking region of the WASP gene. (A) Comparison of the expression of W-CAT5′▵-1,580, W-CAT5′▵-1,167, W-CAT5′▵-988, W-CAT5′▵-829, W-CAT5′▵-365, and W-CAT5′▵-137 in Jurkat cells. (B) Analysis of W-CAT5′▵-137 in Jurkat, HEL, and Dami cells. HeLa cells were used as a negative control.

Expression of CAT constructs carrying progressive 5′ deletion mutants of the flanking region of the WASP gene. (A) Comparison of the expression of W-CAT5′▵-1,580, W-CAT5′▵-1,167, W-CAT5′▵-988, W-CAT5′▵-829, W-CAT5′▵-365, and W-CAT5′▵-137 in Jurkat cells. (B) Analysis of W-CAT5′▵-137 in Jurkat, HEL, and Dami cells. HeLa cells were used as a negative control.

Putative binding sites detected in the 137-bp upstream of the transcription start site of the WASP gene. Solid arrows, Ets-1; dashed arrows, c-Rel and PU.1. The PU.1 consensus was found by comparing the WASP enhancer region with the list of binding sites for vertebrate transcription factors published by Faisst and Meyer35; the Ets-1 and c-Rel consensus were identified by using the TFsearch database (http://www.genome.ad.jp/SIT/TFSEARCH.html). Gray lines indicate the EtsP and EtsD oligonucleotides used in the EMSA assays shown in Fig4.

Putative binding sites detected in the 137-bp upstream of the transcription start site of the WASP gene. Solid arrows, Ets-1; dashed arrows, c-Rel and PU.1. The PU.1 consensus was found by comparing the WASP enhancer region with the list of binding sites for vertebrate transcription factors published by Faisst and Meyer35; the Ets-1 and c-Rel consensus were identified by using the TFsearch database (http://www.genome.ad.jp/SIT/TFSEARCH.html). Gray lines indicate the EtsP and EtsD oligonucleotides used in the EMSA assays shown in Fig4.

(A) EMSA assay of wild-type (W-EtsP, lanes 1-8) and mutant (W-▵EtsP, lanes 9-10) oligonucleotides for the WASP proximal Ets binding site with Jurkat nuclear extracts: labeled oligonucleotide was incubated with Jurkat nuclear extracts as detailed in Materials and Methods and competed with a 50-fold molar excess of the competitors indicated. (B) EMSA assay of wild-type (W-EtsD, lanes 1-8) and mutant (W-▵EtsD, lanes 9-10) oligonucleotides for the WASP distal Ets binding site with Jurkat nuclear extracts: labeled oligonucleotide was incubated with Jurkat nuclear extracts as detailed in Materials and Methods and competed with a 50-fold molar excess of the competitors indicated.

(A) EMSA assay of wild-type (W-EtsP, lanes 1-8) and mutant (W-▵EtsP, lanes 9-10) oligonucleotides for the WASP proximal Ets binding site with Jurkat nuclear extracts: labeled oligonucleotide was incubated with Jurkat nuclear extracts as detailed in Materials and Methods and competed with a 50-fold molar excess of the competitors indicated. (B) EMSA assay of wild-type (W-EtsD, lanes 1-8) and mutant (W-▵EtsD, lanes 9-10) oligonucleotides for the WASP distal Ets binding site with Jurkat nuclear extracts: labeled oligonucleotide was incubated with Jurkat nuclear extracts as detailed in Materials and Methods and competed with a 50-fold molar excess of the competitors indicated.

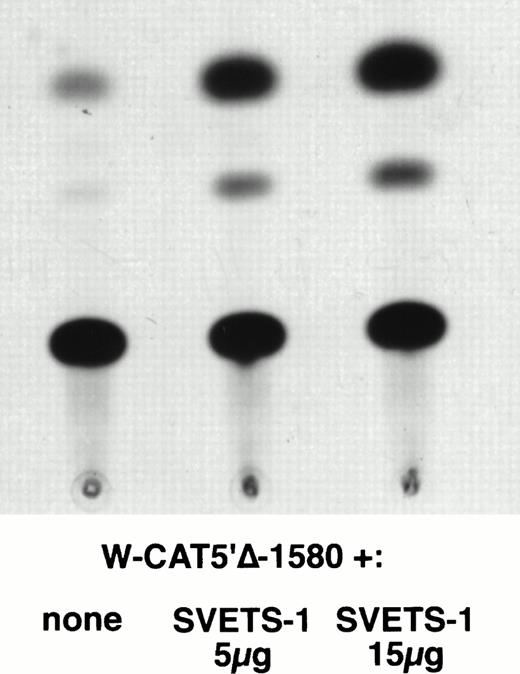

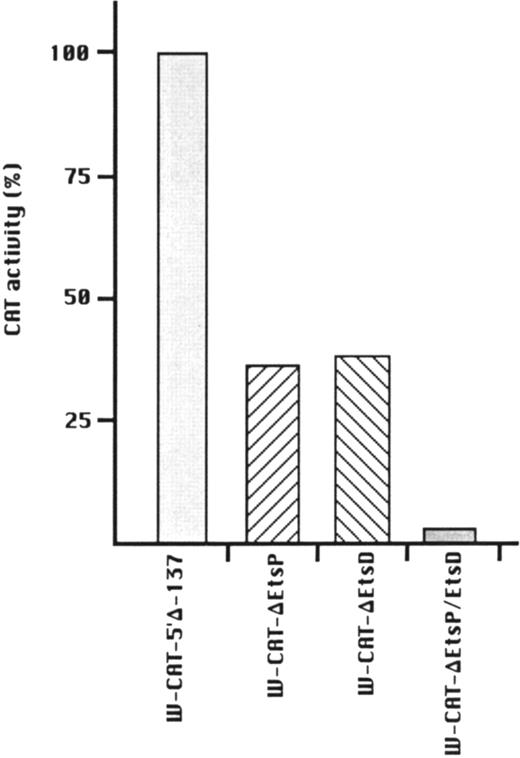

To establish the functional relevance of the Ets-binding sites in the control of WASP expression, two complementary approaches were pursued: (1) HeLa cells, which do not express the endogenous WASP gene nor the CAT reporter gene under the control of the WASP 5′ flanking region, were cotransfected with the construct W-CAT5′Δ-1,580 and the Ets-1 expression vector SVETS-1. As shown in Fig 5, cotransfection with increasing amounts of SVETS-1 resulted in detectable and increasing expression of W-CAT5′Δ-1,580. Similar results were obtained when the construct W-CAT-5′Δ-137 was used (not shown); (2) the Ets sites within the WASP promoter were deleted by PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis. To this end, we designed oligonucleotides identical to W-EtsP and W-EtsD, in which the GGAA core binding sequences were altered as shown in Materials and Methods. When tested in EMSA experiments, both mutant oligonucleotides (W-ΔEtsP and W-ΔEtsD) failed to form specific complexes with Jurkat nuclear factors (Fig 4A and B, lanes 9 and 10) and were unable to compete the binding of the wild-type counterparts (Fig 4A and B, lanes 4 and 6). Thus, W-ΔEtsP and W-ΔEtsD were used to generate by PCR single and double Ets deletion mutants of the construct W-CAT-5′Δ-137, which were termed W-CAT-ΔEtsP, W-CAT-ΔEtsD, and W-CAT-ΔEtsP/ΔEtsD, respectively. Transfection of Jurkat cells with these plasmids (Fig 6) showed that disruption of either the proximal or the distal Ets consensus resulted in a significant decrease in CAT expression (approximately threefold). In the double mutant the transcriptional activity was completely abolished.

Induction of WASP-CAT expression by Ets-1 in HeLa cells. HeLa were cotransfected with W-CAT5′▵-1,580 (15 μg) and with 0, 5, and 15 μg of SVETS-1. Bluescript DNA was added to bring the final amount of DNA to 30 μg. CAT assays were as detailed in Materials and Methods.

Induction of WASP-CAT expression by Ets-1 in HeLa cells. HeLa were cotransfected with W-CAT5′▵-1,580 (15 μg) and with 0, 5, and 15 μg of SVETS-1. Bluescript DNA was added to bring the final amount of DNA to 30 μg. CAT assays were as detailed in Materials and Methods.

Transcriptional activity of WASP-CAT mutant constructs bearing mutations in the proximal (W-CAT-▵EtsP), distal (W-CAT-▵EtsD), or in both Ets binding sites (W-CAT-▵EtsP/▵EtsD). CAT activity is expressed as percentage of the wild-type construct, W-CAT-5′▵-137.

Transcriptional activity of WASP-CAT mutant constructs bearing mutations in the proximal (W-CAT-▵EtsP), distal (W-CAT-▵EtsD), or in both Ets binding sites (W-CAT-▵EtsP/▵EtsD). CAT activity is expressed as percentage of the wild-type construct, W-CAT-5′▵-137.

DISCUSSION

WASP is the gene whose alterations are responsible for the occurrence of WAS and of the related disease, isolated X-linked thrombocytopenia.3-5 Increasing evidence indicates that the WASP protein is involved in signal transduction as well as in the control of cytoskeletal organization.6-9 Recently, additional molecules have been identified that share amino acid homology with specific domains of WASP and are believed to possess a similar function,23-25 delineating the existence of a WASP-related superfamily of proteins. Nevertheless, WASP appears to be a nonredundant molecule, because lack of functional protein produces the Wiskott-Aldrich or the XLT phenotype. This may be explained either by functional differences between WASP and related molecules, or by the fact that expression of different members of the family may be restricted to different tissues. Indeed, although one report has described detection of WASP in nonhematopoietic cells,26 a vast consensus of findings strongly supports the notion that WASP expression is regulated in a developmental- and tissue-specific manner with high levels of its transcript being present only in the hematopoietic system and particularly in fetal thymus and spleen as well as in human hematopoietic cell lines (our unpublished results, Derry et al,1 Stewart et al,27 and Parolini et al28). WASP appears to be required in early stages of development of the hematopoietic system because, in female obligate carriers of WAS, the X chromosome bearing the mutation is nonrandomly inactivated in all hematopoietic cells, including highly immature progenitors.29

In this report we have isolated, sequenced, and studied the 5′ flanking region of the WASP gene. In keeping with the observation of Derry et al,21 on the first 500 bp of this region, no obvious TATA consensus nor SP1-binding sites were detected immediately upstream of the coding sequence, although the region encompassing the transcription start site shares some similarity with the initiator-like motif of the adenovirus major-late promoter.22. Lack of a TATA box is a feature common to several genes expressed in hematopoietic cells; however, the question remained whether an additional exon may be located further upstream. To address this issue, we mapped the transcription initiation point of WASP by 5′ RACE and found one major transcription start site at position −13 with respect to the first nucleotide of the WASP cDNA isolated by Derry et al.1 It cannot, of course, be excluded that additional transcriptional initiation points could exist; RNA protection assays and/or S1 mapping experiments may yield further information about the possible presence of alternative start sites.

Transfection experiments with constructs carrying the whole −1,580/+33 fragment or progressive 5′ deletions showed that the region between nt −137 and +33 was necessary and sufficient to confer strong, hematopoietic-specific expression on the CAT reporter gene. Sequence analysis showed the presence within this fragment of potential binding sites for transcription factors known to be expressed in hematopoietic cells (Fig 3). In particular, three partially overlapping sequences are located next to the initiation of transcription, which match the consensus for Ets-1, c-Rel, and PU.1 (in inverted orientation), respectively. An additional putative Ets-1 binding site (in inverted orientation) was detected approximately 20 bp upstream. EMSA experiments showed that a protein(s) capable of binding to both Ets sites within the WASP promoter was present in Jurkat nuclear extracts (Fig 4A and B). In HeLa cells (which do not express WASP) the WASP-CAT construct was strongly transactivated by cotransfection with an Ets-1 expression vector (Fig 5). Finally, mutagenesis of either Ets motif within the WASP promoter, which abolished the binding, was accompanied by a significant decrease in CAT expression in Jurkat cells, and disruption of both sites resulted in complete loss of expression (Fig 6). These data clearly show that the Ets-binding sites in the WASP promoter are indispensable for expression in hematopoietic cells. The identity of the factor(s) that bind to the two Ets consensus in the WASP regulatory region remains to be determined. Ets-1, widely expressed within the hematopoietic system, abundant in T cells,30 and implicated in the transcriptional control of several lymphoid and myeloid genes,31,32 induces transactivation of WASP-CAT constructs in HeLa cells, and it would be tempting to speculate that this may indeed be the factor required for WASP transcription in hematopoietic cells in vivo. However, the data so far available are not sufficient to support this hypothesis, because the ETS family includes a variety of transcription factors that interact with similar or identical sequences on target genes.33 Studies with recombinant Ets proteins and transfection experiments in cell lines selectively expressing distinct factors will help clarify this issue. Another open question regards the possible role of PU.1, itself a component of the Ets family, which recognizes a motif slightly divergent from that of most cognate factors.33 PU.1 has been implicated in the regulation of hematopoietic genes, in particular in megakaryocytic and B-lymphoid cells.34 In EMSA experiments on HEL nuclear extracts (not shown), it specifically binds to its consensus sequence within the WASP promoter. However, PU.1 is absent in T lymphocytes and Jurkat cells, which strongly express WASP; therefore its role, if any, must be accessory and restricted to PU.1-producing cell lineages. Preliminary data (not shown) suggest that in megakaryocytic cells PU.1 may act as a negative regulator of WASP expression.

In conclusion, in this report we have identified a hematopoietic-specific WASP promoter and established the essential importance of Ets factors in the transcriptional regulation of this gene. The information gained in this work may contribute to the recognition of molecular lesions responsible for cases of WAS and/or XLT without apparent mutations within the WASP coding sequence. In addition, the knowledge of the cis-acting sequences and trans-acting factors, which control the transcription of WASP, will be of value for the development of expression vectors capable of directing the expression of WASP in a physiological manner and suitable for a rational gene therapy approach for WAS and XLT.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The skillful technical assistance of Mrs Rita Bisogni and of Mr Carmine Del Gaudio is gratefully acknowledged. We are grateful to Dr N. Taniguchi for providing the vector SVETS-1. We are indebted to Drs Luigi Notarangelo and F. Costanzo for discussion of the data and for their valuable suggestions and criticisms.

Supported by funds from Telethon, from the Italian Association for Cancer Research (AIRC), and from the Consiglio Nazionale delle Recerche (CNR).

Address reprint requests to G. Morrone, MD, CEINGE Advanced Biotechnology, c/o Department of Biochemistry and Medical Biotechnology, Via S Pansini, 5, 80131 Napoli, Italy.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked "advertisement" is accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal