Abstract

Peripheral blood progenitor cells (PBPC) are increasingly being used in the clinic as a replacement for bone marrow (BM) in the transplantation setting. We investigated the capacity of several different growth factors, including human flt3 ligand (FL), alone and in combination with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF ) or granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF ), to mobilize colony forming cells (CFU) into the peripheral blood (PB) of mice. Mice were injected subcutaneously (SC) with growth factors daily for up to 10 days. Comparing the single agents, we found that FL alone was superior to GM-CSF or G-CSF in mobilizing CFU into the PB. FL synergized with both GM-CSF or G-CSF to mobilize more CFU, and in a shorter period of time, than did any single agent. Administration of FL plus G-CSF for 6 days resulted in a 1,423-fold and 2,717-fold increase of colony-forming unit–granulocyte-macrophage (CFU-GM) and colony-forming unit granulocyte, erythroid, monocyte, megakaryocyte (CFU-GEMM) in PB, respectively, when compared with control mice. We also followed the kinetics of CFU numerical changes in the BM of mice treated with growth factors. While GM-CSF and G-CSF alone had little effect on BM CFU over time, FL alone increased CFU-GM and CFU-GEMM threefold and fivefold, respectively. Addition of GM-CSF or G-CSF to FL did not increase CFU in BM over levels seen with FL alone. However, after the initial increase in BM CFU after FL plus G-CSF treatment for 3 days, BM CFU returned to control levels after 5 days treatment, and CFU-GM were significantly reduced (65%) after 7 days treatment, when compared with control mice. Finally, we found that transplantation of FL or FL plus G-CSF–mobilized PB cells protected lethally irradiated mice and resulted in long-term multilineage hematopoietic reconstitution.

RECOVERY FROM HIGH-DOSE chemotherapy has been enhanced by the use of autologous and allogeneic bone marrow (BM) transplantation. Over the past 10 years there has been a trend to replace BM as a source of hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) with growth factors and/or chemotherapy-mobilized peripheral blood progenitor cells (PBPC). Evidence suggests that using mobilized PBPC instead of BM leads to a more rapid hematopoietic reconstitution.1,2 PBPC in steady state are rare; however, their numbers can be increased by mobilizing with chemotherapeutic agents such as cyclophosphamide.3 Growth factors that have also been shown to mobilize PBPC include granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF ),4-6 granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF ),7,8 c-kit ligand (KL) (also known as mast cell growth factor, Steel factor, and stem cell factor),9 interleukin-12 (IL-12),10 IL-7,11 and the chemokines macrophage inflammatory protein-1α (MIP-1α) (BB10010)12 and IL-8.13

FL is a type 1 transmembrane protein that exists in both membrane-bound and soluble forms.14-16 FL mRNA has been detected by Northern blot analysis in both hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic tissues, as well as in many hematopoietic cell lines surveyed.14-18 This is in contrast to flt3 receptor19 (also known as flk-220 or STK-121 ) expression in the hematopoietic system, which is restricted primarily to adult mouse BM cells, and progenitor cells of the adult thymus, fetal thymus, and fetal liver.20 FL alone or in combination with other growth factors stimulates the proliferation of highly enriched human and murine HSC in vitro.14-16,22-24 Targeted disruption of the flt3 gene leads to a deficiency of B-cell precursors and multipotential stem cells.25

We recently described the effects of administration of recombinant human FL to mice.26 Mice treated with recombinant FL have increased numbers of CFU in BM, spleen, and PB. In this report, we investigated mobilization of PBPC using FL in combination with GM-CSF or G-CSF. FL synergized with GM-CSF or G-CSF to increase white blood cell (WBC) numbers, as well as CFU in the PB, as assessed by in vitro colony assays. Mobilized cells into the PB after FL treatment also had the capacity to rescue and reconstitute multiple hematopoietic lineages in irradiated animals. Our data show that FL synergizes with GM-CSF or G-CSF to mobilize large numbers of PBPC, suggesting a potential clinical use in a transplantation setting.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental design. Female C57BL/6J mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) or C57BL/6-Ly5.2 mice (NCI/Frederick Cancer Research Center, Frederick, MD), 8 to 12 weeks old (19 to 21 g of body weight) were used in experiments for evaluation of BM and PB CFU, and as donor mice in reconstitution studies, respectively. Mice were housed in a specific pathogen-free facility. Mice were injected once daily, subcutaneously (SC) with recombinant cytokines in 0.1 mL low endotoxin phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 10 μg/mL mouse serum albumin (MSA) as a carrier (Sigma Chemical Co, St Louis, MO). Injections were started on day 0. For each experiment, three to four mice per group per time point were used. PB was pooled from mice within each treatment group for analysis.

Growth factors. All growth factors were injected SC at 10 μg/mouse/day in a total volume of 100 μL. Chinese hamster ovary (CHO)-cell–derived human FL (Immunex Corp, Seattle, WA),26 yeast-cell–derived murine GM-CSF (Immunex Corp),27 and Escherichia coli–derived human G-CSF (Amgen Inc, Thousand Oaks, CA) each contained less than 0.15 ng endotoxin/mg protein.

Tissues. Isolation and preparation of PB and BM tissues for analysis has been previously described.26 Briefly, PB cells were collected from anesthetized mice via cardiac puncture into heparinized tubes (Venoject; Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMNC) were isolated after centrifugation of blood over a discontinuous gradient using Lympholyte-M (Cedarlane, Ontario, Canada). The PBMNC were collected and washed twice in supplemented McCoys-5a medium (SM) plus 5% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS). After individual PBMNC counts were performed, cells from mice within each group were pooled (because of low frequency of CFU in control mice) for analysis (in vitro colony assays and in vivo reconstitution).

BM cells from femurs were aseptically removed and collected into cold PBS. Single cell suspensions were washed once and resuspended in SM plus 5% FBS. Cell counts and colony assays were performed using individual BM samples.

In vitro colony assay. The frequency of granulocyte/macrophage colony forming units (CFU-GM) and granulocyte, erythroid, macrophage, megakaryocyte colony-forming units (CFU-GEMM) in BM and PB were assessed using methylcellulose based colony assays. Cells from the BM or PBMNC were seeded in the colony assays at different cell numbers (twofold to threefold increments) depending on the specific tissue and prior treatment. The plating efficiency of CFU was linear and extrapolated to zero. Colony assays were performed using a methylcellulose based medium (HCC-3230; Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada) supplemented with 100 ng/mL murine IL-3 (Immunex), 200 ng/mL murine KL (Immunex), 2 U/mL human erythropoietin (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), and 0.2 mmol/L hemin (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY). Colony assays were plated in quadruplicate wells at 0.5 mL/well in 24-well plates (Costar, Cambridge, MA). Plates were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 6.5% CO2 in air. Colonies containing more than 50 cells were scored after 9 days of culture.

Irradiation survival and analysis of hematopoietic reconstitution by donor cells. Adult (4 to 6 months old) female C57BL/6J recipients were irradiated with 1,000 rads (R) using a 137Cs source (Mark 1 Irradiator; J.L. Shepherd and Associates, Glendale, CA) at a dose rate of 89 R/minute, and mice were injected 3 to 4 hours later with donor cells. Pooled donor PBMNC from mice treated daily for 10 days with 1 μg MSA or MSA plus FL (10 μg) (5 × 105 or 1 × 105 cells) or control (MSA) BM cells (2 × 105) were injected intravenously (IV) into the lateral tail vein of irradiated recipient mice. Fifteen recipient mice were injected with cells from the irradiation control, FL high dose (5 × 105) and FL + G-CSF high dose (5 × 105) groups, 14 mice were injected with control MSA PBMNC, and the remaining groups (control BM, FL low dose, and FL + G-CSF low dose) consisted of 10 recipient mice. Survival was assessed to 30 days postirradiation. Reconstitution by donor cells was examined by flow cytometry 30 days and 6 months postirradiation. Three mice per group were harvested for thymus, spleen (6 months only), and BM tissue for phenotypic analysis (see below).

Flow cytometry. For detection of Ly5.2 expressing donor derived cells, BM, spleen, and thymus tissue from recipient mice was collected. Tissue was minced into a single cell suspension, then washed in staining media (PBS with 3% FBS and 0.02% sodium azide) before blocking 30 minutes with staining media supplemented with 10% heat inactivated goat serum and 20 μg/mL antimouse Fc receptor monoclonal antibody (MoAb) 2.4G2 (ATCC, Rockville, MD). One million cells per sample were stained in a 50 μL volume for 30 minutes at 4°C. Donor (Ly5.2)-derived cells were detected with MoAb A20-Fitc (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA). The A20 MoAb recognizes the Ly5.2 antigen (also known as CD45.1) expressed on nucleated hematopoietic cells.28 These same cells were also labeled with MoAbs specific for various hematopoietic lineages: B220-phycoerythrin (PE), MAC1-PE, GR-1-PE, Thy 1.2-PE. These MoAbs, along with isotype control MoAbs, were purchased from Pharmingen. All MoAbs were used at predetermined optimal concentrations. For phenotypic analysis, 10,000 events were acquired using the FACsan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). Analysis of the acquired data was performed using Lysis II software (Becton Dickinson).

Statistical analysis. Statistical analyses were performed using unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test and the 30-day survival was assessed using Kaplan-Meier estimates.

RESULTS

Mobilization of CFU-GM and CFU-GEMM into the PB of mice treated with growth factors. We evaluated the effects of administration of recombinant FL, G-CSF, GM-CSF, or combinations of FL with G-CSF or GM-CSF (each growth factor at 10 μg/d) in mice by analyzing WBC and circulating CFU numbers over time. Mice were treated for up to 10 days with growth factor(s), and cohorts were killed for analysis. The changes in WBC numbers as a result of growth factor administration are shown in Fig 1. The maximal increase in WBC numbers compared with MSA injected control mice was seen after 6 days of treatment with FL plus G-CSF (21-fold). Although administration of FL plus G-CSF continued for 4 more days, WBC numbers began to decline from day 6 levels. The majority of the cells in the PB after FL plus G-CSF treatment were neutrophilic granulocytes (data not shown). Growth factor treatment increased PBMNC numbers to a similar degree as WBC (data not shown). FL plus GM-CSF gave a maximal WBC increase (sixfold) after 10 days of growth factor treatment. Neither GM-CSF nor G-CSF as single agents with this dosing regimen had a major impact on circulating WBC levels. FL alone led to a modest increase (fourfold) in circulating WBC. All WBC counts had returned to pretreatment levels 7 days after cessation of growth factor treatment.

Effects of growth factor administration on WBC numbers. Mice were injected SC with 1 μg MSA or MSA plus growth factor (each at 10 μg) daily for up to 10 days. Four mice per group were killed after 2, 4, 6, and 10 days growth factor treatment, as well as 7 days postcessation of treatment. The following symbols were used to represent each growth factor–treated group of mice: FL (•); G-CSF (▪); GM-CSF (▾); FL plus G-CSF (□); and FL plus GM-CSF (▿). The average WBC count in MSA control mice was 4.4 ± 1.7 × 106/mL blood. This experiment was performed twice giving very similar results (only differing in the route of injection [IP] and dosage of G-CSF and GM-CSF [5 μg/mouse/d]). Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM). WBC counts that differed significantly (P < .005) from MSA controls are marked (*).

Effects of growth factor administration on WBC numbers. Mice were injected SC with 1 μg MSA or MSA plus growth factor (each at 10 μg) daily for up to 10 days. Four mice per group were killed after 2, 4, 6, and 10 days growth factor treatment, as well as 7 days postcessation of treatment. The following symbols were used to represent each growth factor–treated group of mice: FL (•); G-CSF (▪); GM-CSF (▾); FL plus G-CSF (□); and FL plus GM-CSF (▿). The average WBC count in MSA control mice was 4.4 ± 1.7 × 106/mL blood. This experiment was performed twice giving very similar results (only differing in the route of injection [IP] and dosage of G-CSF and GM-CSF [5 μg/mouse/d]). Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM). WBC counts that differed significantly (P < .005) from MSA controls are marked (*).

To quantitate the mobilization of PBPC in mice treated with growth factors, we measured CFU-GM and CFU-GEMM using an in vitro colony assay. Comparing the capacity of single growth factors to mobilize and increase CFU frequency in the PB of mice, G-CSF increased the frequency of CFU-GM and CFU-GEMM in PB after 4 and 2 days treatment, respectively (Fig 2A and B, respectively). The frequency of CFU in PB increased only slightly higher even after continued administration of G-CSF. GM-CSF at this dose and schedule did not increase the frequency of CFU in the PB of mice, in contrast to its documented efficacy in humans.4-6 The relative inactivity on hematopoiesis of unmodified-recombinant GM-CSF administered to mice has been reported previously.29 There was an increase in the frequency of both CFU-GM and CFU-GEMM in PB as early as 6 and 4 days after treatment with FL alone, respectively. The frequency of CFU-GM in PB continued to increase with further FL treatment, surpassing that obtained with G-CSF alone by approximately fivefold (10 days treatment). Seven days after cessation of G-CSF or FL treatment, circulating CFU had almost returned to normal (data not shown).

Mobilization of CFU into the PB after growth factor administration. (A and B) The frequency of CFU-GM and CFU-GEMM (per 105 cells) in PB after 2, 4, 6, and 10 days growth factor treatment, respectively. (C and D) The absolute number of CFU-GM and CFU-GEMM per mL of PB (PBMNC count multiplied by CFU frequency) after 2, 4, 6, and 10 days growth factor treatment, respectively. PBMNC from four mice were pooled within each group for CFU assays (see Materials and Methods). In all growth factor-treated groups, total CFU per mL of PB and CFU frequency per 105 cells had almost returned to pretreatment values 1 week postgrowth factor treatment (data not shown). This experiment was performed twice giving very similar results (only differing in the route of injection [IP] and dosage of G-CSF and GM-CSF [5 μg/mouse/d]).

Mobilization of CFU into the PB after growth factor administration. (A and B) The frequency of CFU-GM and CFU-GEMM (per 105 cells) in PB after 2, 4, 6, and 10 days growth factor treatment, respectively. (C and D) The absolute number of CFU-GM and CFU-GEMM per mL of PB (PBMNC count multiplied by CFU frequency) after 2, 4, 6, and 10 days growth factor treatment, respectively. PBMNC from four mice were pooled within each group for CFU assays (see Materials and Methods). In all growth factor-treated groups, total CFU per mL of PB and CFU frequency per 105 cells had almost returned to pretreatment values 1 week postgrowth factor treatment (data not shown). This experiment was performed twice giving very similar results (only differing in the route of injection [IP] and dosage of G-CSF and GM-CSF [5 μg/mouse/d]).

Although treatment with GM-CSF alone did not increase the frequency of CFU in the PB of mice, it did synergize with FL after 2 to 6 days of combined treatment (Fig 2A and B). However, after 10 days treatment, CFU-GM and CFU-GEMM were more frequent in the PB of mice treated with FL alone compared with FL plus GM-CSF. G-CSF also synergized with FL to mobilize CFU into the PB of mice. Like GM-CSF, G-CSF synergized with FL to increase CFU frequency after 2 to 6 days of treatment, but CFU frequency decreased after 10 days FL plus G-CSF treatment to below levels obtained with FL alone.

The absolute number of circulating CFUs in blood is a function of the frequency of CFU multiplied by the total number of PBMNC in treated mice. The absolute number of circulating CFU-GM and CFU-GEMM per mL of PB during 10 days of growth factor treatment are shown in Fig 2C and D. G-CSF mobilized CFU-GM into the PB of mice after 4 days of treatment, giving a maximal increase of 30-fold over control mice treated with MSA. CFU remained elevated above control levels after 10 days treatment. CFU-GEMM also began to increase after 4 days treatment with G-CSF, but maximal numbers were not achieved until 10 days treatment (63-fold increase).

There was a noticeable increase in CFU-GM and CFU-GEMM after 6 days treatment with FL alone (Fig 2C and D). CFU continued to increase with further administration of FL for another 4 days (184-fold for both CFU-GM and CFU-GEMM). FL synergized with G-CSF, and to a lesser degree with GM-CSF, to mobilize CFU into the PB of mice. The synergistic effect of FL plus G-CSF was maximal after 6 days of treatment for both CFU-GM and CFU-GEMM (1,423- and 2,717-fold increase over control MSA-treated mice, respectively). After 10 days of treatment, CFU-GM were still elevated, but CFU-GEMM had decreased below detectable levels (Fig 2D). CFU numbers had almost returned to pretreatment levels 1 week after growth factor treatment (data not shown).

BM CFU-GM and CFU-GEMM in mice treated with growth factors. Because PBPC mobilized by growth factors or chemotherapy are frequently compared with BM1,30 we also examined the kinetics of growth factor-mediated expansion of CFU within BM. Groups of three mice were treated with FL, G-CSF, GM-CSF, FL plus G-CSF, or FL plus GM-CSF (each growth factor at 10 μg/d) for up to 7 days. During the treatment regimen, mice were periodically killed for quantitation of BM cellularity, CFU-GM, and CFU-GEMM. There was no significant effect of growth factor treatment on BM leukocyte numbers with the exception of the 7-day time point for treatment with FL alone or FL plus G-CSF, where both treatments increased cellularity 30% to 40% (data not shown).

BM cells from mice treated with growth factors for up to 7 days were assayed in an in vitro colony assay to quantitate CFU-GM and CFU-GEMM. There was no significant change in BM CFU-GM or CFU-GEMM after G-CSF or GM-CSF administration for 5 or 7 days treatment, respectively (Table 1). However, there was a significant increase (threefold) in BM CFU-GM after 3 days treatment with FL alone, FL plus G-CSF, or FL plus GM-CSF. This increase appeared to be due to the FL, as there was no increase in CFU with the addition of G-CSF or GM-CSF to FL alone. Administration of FL alone for 5 or 7 days resulted in a nearly fourfold elevation of CFU-GM levels. In contrast to treatment with FL alone, there was a dramatic decrease in BM CFU-GM after 7 days treatment with FL plus G-CSF (reduced 64% v MSA-treated control).

Effect of Growth Factor Treatment on BM Progenitors

| Treatment Group . | CFU-GM (×103) . | CFU-GEMM (×102) . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Day 1 . | Day 3 . | Day 5 . | Day 7 . | Day 1 . | Day 3 . | Day 5 . | Day 7 . |

| MSA | 87 ± 3* | 86 ± 15 | 78 ± 11 | 76 ± 9 | BD† | 15 ± 5 | 16 ± 7 | 19 ± 6 |

| FL | 109 ± 9 | 269 ± 50‡ | 295 ± 34‡ | 287 ± 55‡ | 25 ± 25 | 64 ± 18‡ | 89 ± 24‡ | 27 ± 3 |

| G-CSF | 97 ± 10 | 94 ± 6 | 86 ± 12 | ND | 34 ± 3 | 35 ± 4 | 24 ± 12 | ND |

| GM-CSF | 82 ± 18 | 93 ± 9 | 85 ± 12 | 80 ± 6 | 27 ± 9 | 24 ± 3 | 31 ± 7 | 27 ± 15 |

| FL + G-CSF | 108 ± 14 | 304 ± 13‡ | 54 ± 3 | 27 ± 2‡ | 26 ± 13 | 62 ± 10‡ | 15 ± 1 | BD |

| FL + GM-CSF | 75 ± 6 | 283 ± 27‡ | 268 ± 40‡ | 171 ± 26‡ | 50 ± 11 | 77 ± 28 | 67 ± 7‡ | 16 ± 7 |

| Treatment Group . | CFU-GM (×103) . | CFU-GEMM (×102) . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Day 1 . | Day 3 . | Day 5 . | Day 7 . | Day 1 . | Day 3 . | Day 5 . | Day 7 . |

| MSA | 87 ± 3* | 86 ± 15 | 78 ± 11 | 76 ± 9 | BD† | 15 ± 5 | 16 ± 7 | 19 ± 6 |

| FL | 109 ± 9 | 269 ± 50‡ | 295 ± 34‡ | 287 ± 55‡ | 25 ± 25 | 64 ± 18‡ | 89 ± 24‡ | 27 ± 3 |

| G-CSF | 97 ± 10 | 94 ± 6 | 86 ± 12 | ND | 34 ± 3 | 35 ± 4 | 24 ± 12 | ND |

| GM-CSF | 82 ± 18 | 93 ± 9 | 85 ± 12 | 80 ± 6 | 27 ± 9 | 24 ± 3 | 31 ± 7 | 27 ± 15 |

| FL + G-CSF | 108 ± 14 | 304 ± 13‡ | 54 ± 3 | 27 ± 2‡ | 26 ± 13 | 62 ± 10‡ | 15 ± 1 | BD |

| FL + GM-CSF | 75 ± 6 | 283 ± 27‡ | 268 ± 40‡ | 171 ± 26‡ | 50 ± 11 | 77 ± 28 | 67 ± 7‡ | 16 ± 7 |

Mice were treated daily (SC) with 1 μg MSA (control) or MSA plus each growth factor (10 μg/d) for up to 7 days. On days 1 (24 hours after the first injection), 3, 5, and 7, mice (N = 3) were killed and BM (2 femurs/mouse) was assessed for CFU numbers. BM samples from each animal were plated separately at various cell densities depending on previous growth factor treatment. Only colonies consisting of 50 or more cells were scored. Day 1 CFU-GEMM results from MSA-treated mice were below detectable levels, thus they could not be compared against growth factor-treated mice for statistical analysis.

Abbreviation: ND, not done.

Mean ± SEM per 2 femurs.

BD, below limit of detection (<500 CFU-GEMM/2 femurs).

Significantly increased or decreased when compared to MSA control (P < .05).

Neither G-CSF nor GM-CSF significantly elevated BM CFU-GEMM levels at any of the timepoints examined (Table 1). FL alone significantly increased CFU-GEMM after 3 and 5 days treatment (fourfold and sixfold increase, respectively), but returned to control levels after 7 days treatment. FL plus G-CSF treatment for 3 days significantly increased CFU-GEMM similar to FL alone, but after 5 days treatment the CFU returned to control levels, and decreased below detectable levels after 7 days treatment. GM-CSF did not synergize with FL to increase BM CFU-GEMM over levels obtained with FL alone.

With such a profound loss in BM-derived CFU after FL plus G-CSF treatment, we investigated whether CFU could be mobilized again in mice previously treated with FL plus G-CSF, after a 2-week resting period. Mice treated with FL plus G-CSF for 6 days mobilized as many CFU-GM and CFU-GEMM in the second round of mobilization as measured in the first round (data not shown). This suggests that PBPC mobilized by FL plus G-CSF treatment are replenished and can be mobilized again after a short resting period.

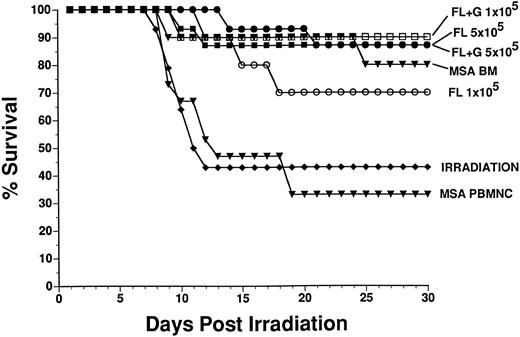

Short-term and long-term reconstitution of multiple hematopoietic lineages in irradiated mice by mobilized PBPC. To determine whether FL or FL plus G-CSF-mobilized PBMNC could rescue irradiated mice and reconstitute the myeloid and lymphoid lineages of recipients, we irradiated recipient mice, then injected them with PBMNC obtained from donor mice that had been treated for 10 days with either 1 μg/d MSA, MSA plus 10 μg/d FL or 6 days with MSA, and 10 μg/d FL plus G-CSF. The donor BM and PBMNC were derived from C57BL/6-Ly5.2 mice and the irradiated recipients were congenic C57BL/6J (Ly5.1) mice. Donor and host derived cells were distinguished by flow cytometry using specific MoAbs. Survival of recipient mice was followed for 30 days, at which time a proportion of surviving mice were killed and short-term reconstitution of hematopoietic lineages by donor cells was evaluated by flow cytometry. Long-term reconstitution was evaluated 6 months postirradiation also by flow cytometry. The 30-day survival of irradiated mice rescued with cells from normal BM, PBMNC from MSA-treated mice (control), FL-treated mice, and FL + G-CSF–treated mice are presented in Fig 3. There was 43% survival in the irradiation control group and 33% survival in the group injected with control PBMNC (5 × 105 cells, which represents 128 μL whole PB). The positive control, normal BM (2 × 105 cells) from MSA-treated mice, rescued 80% of irradiated mice. Injection of FL treated donor PBMNC at 5 × 105 cells/mouse or 1 × 105 cells/mouse (representing 30 and 6 μL whole PB, respectively) rescued 87% and 70% of recipient mice, respectively. PBMNC from donor mice treated with FL + G-CSF rescued 87% and 90% of mice injected with 5 × 105 and 1 × 105 cells (representing 6 and 1.2 μL whole PB, respectively), respectively. There was no significant difference in survival amoung the groups of mice reconstituted with cells from control BM, FL or FL + G-CSF. Although the dose of irradiation we chose (1,000 R) was not lethal to 100% of the irradiation control mice, there was significantly greater survival in mice reconstituted with high dose (5 × 105 cells) PBMNC from FL treated mice and both doses (5 × 105 or 1 × 105 cells) of PBMNC from FL + G-CSF-treated donor mice, when compared with the irradiation control group (P = .0067, .0104, and .0238, respectively) or when compared with the control PBMNC group (P = .0015, .0033, and .0085, respectively).

Survival (30 days) of irradiated recipients (Ly5.1) transplanted with donor (Ly5.2)-derived BM cells or PBMNC from control or FL-treated mice. Donor mice were treated once daily for 10 days with 1 μg MSA (control PBMNC and BM) or MSA plus 10 μg FL SC. Donor PBMNC (5 × 105 or 1 × 105 cells/mouse) or BM (2 × 105 cells/mouse) were injected IV 3 to 4 hours postirradiation into recipient mice (10 to 15 mice per group). There was significantly greater survival from mice reconstituted with control BM and PBMNC (5 × 105 cells) from FL or FL + G-CSF–treated mice when compared with irradiation control or control PBMNC groups (see Results).

Survival (30 days) of irradiated recipients (Ly5.1) transplanted with donor (Ly5.2)-derived BM cells or PBMNC from control or FL-treated mice. Donor mice were treated once daily for 10 days with 1 μg MSA (control PBMNC and BM) or MSA plus 10 μg FL SC. Donor PBMNC (5 × 105 or 1 × 105 cells/mouse) or BM (2 × 105 cells/mouse) were injected IV 3 to 4 hours postirradiation into recipient mice (10 to 15 mice per group). There was significantly greater survival from mice reconstituted with control BM and PBMNC (5 × 105 cells) from FL or FL + G-CSF–treated mice when compared with irradiation control or control PBMNC groups (see Results).

Thirty days postirradiation (short-term), three mice from each group were killed for phenotypic analysis of BM and thymus to assess the degree of hematopoietic lineage reconstitution by Ly5.2+ donor cells. The mean percentage of donor cells and range (determined by staining with antibody for Ly5.2) within each lineage (T lymphoid, B lymphoid, and myeloid) is presented in Table 2. Donor BM from control mice reconstituted 99%, 80%, and 36% of T lymphoid, B lymphoid, and myeloid cells, respectively. In contrast, mice injected with PBMNC obtained from MSA-treated donor mice resulted in no reconstitution by donor cells. All lineages in these mice were reconstituted, but they were entirely host-derived (data not shown). In recipient mice injected with PBMNC from mice treated with FL or FL plus G-CSF, all hematopoietic lineages tested were reconstituted with donor Ly5.2 expressing cells. There was no significant difference in the percent donor reconstitution of T-cell or myeloid lineages when comparing mice injected with control BM cells versus mice injected with PBMNC from mobilized (FL or FL plus G-CSF ) donors. However, there was significantly greater reconstitution of the B-cell lineage in mice reconstituted with cells from control BM versus PBMNC from mice mobilized with FL (both doses of PBMNC) or FL plus G-CSF (high-dose PBMNC only) (P < .02).

Short-Term and Long-Term Reconstitution of Hematopoietic Lineages by Mobilized PB

| . | Short-Term Reconstitution (1 mo) . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Source of Reconstituting Cells (no. cells injected) . | Control PB (5 × 105) . | FL PB . | FL PB . | FL + G-CSF PB . | FL + G-CSF PB . |

| . | Control BM (2 × 105) . | . | (5 × 105) . | (1 × 105) . | (5 × 105) . | (1 × 105) . |

| Lineage . | % Donor Phenotype (range) . | |||||

| . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| T cell | 99 (97-100) | 0 (0) | 64 (44-88) | 48 (15-91) | 73 (32-97) | 47 (6-94) |

| B cell | 80 (74-88) | 1 (0-2) | 35 (22-57) | 24 (8-53) | 46 (44-49) | 39 (5-63) |

| Myeloid | 36 (19-63) | 0 (0-1) | 18 (16-21) | 26 (0-70) | 38 (6-62) | 12 (1-31) |

| . | Short-Term Reconstitution (1 mo) . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Source of Reconstituting Cells (no. cells injected) . | Control PB (5 × 105) . | FL PB . | FL PB . | FL + G-CSF PB . | FL + G-CSF PB . |

| . | Control BM (2 × 105) . | . | (5 × 105) . | (1 × 105) . | (5 × 105) . | (1 × 105) . |

| Lineage . | % Donor Phenotype (range) . | |||||

| . | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| T cell | 99 (97-100) | 0 (0) | 64 (44-88) | 48 (15-91) | 73 (32-97) | 47 (6-94) |

| B cell | 80 (74-88) | 1 (0-2) | 35 (22-57) | 24 (8-53) | 46 (44-49) | 39 (5-63) |

| Myeloid | 36 (19-63) | 0 (0-1) | 18 (16-21) | 26 (0-70) | 38 (6-62) | 12 (1-31) |

| . | Long-Term Reconstitution (6 mo) . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Control BM (2 × 105) . | Control PB (5 × 105) . | FL PB (5 × 105) . | FL PB (1 × 105) . | FL + G-CSF PB (5 × 105) . | FL + G-CSF PB (1 × 105) . |

| T cell | 76 (65-86) | 3 (3) | 48 (12-74) | 10 (5-14) | 14 (9-17) | 11 (6-14) |

| B cell | 88 (76-99) | 0 (0) | 55 (29-79) | 4 (3-5) | 36 (25-46) | 15 (7-19) |

| Myeloid | 74 (63-85) | 0 (0) | 63 (48-88) | 10 (7-14) | 39 (31-50) | 20 (12-28) |

| . | Long-Term Reconstitution (6 mo) . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Control BM (2 × 105) . | Control PB (5 × 105) . | FL PB (5 × 105) . | FL PB (1 × 105) . | FL + G-CSF PB (5 × 105) . | FL + G-CSF PB (1 × 105) . |

| T cell | 76 (65-86) | 3 (3) | 48 (12-74) | 10 (5-14) | 14 (9-17) | 11 (6-14) |

| B cell | 88 (76-99) | 0 (0) | 55 (29-79) | 4 (3-5) | 36 (25-46) | 15 (7-19) |

| Myeloid | 74 (63-85) | 0 (0) | 63 (48-88) | 10 (7-14) | 39 (31-50) | 20 (12-28) |

C57BL/6 mice (Ly5.1+) were irradiated with 1,000 R, then injected IV 3 to 4 hours later with congenic donor cells (Ly5.2+). Control BM cells and PBMNC were isolated from donor mice treated for 10 days with MSA (1 μg/mouse/d). PBMNC were also collected from donor mice treated with MSA plus FL (10 μg/mouse/d) for 10 days or MSA plus FL and G-CSF (both at 10 μg/mouse/d) for 6 days. Ten to 15 recipient mice were injected with donor cells from each respective group. Three mice per group were harvested 30 days (short-term) or 6 months (long-term) postirradiation to evaluate donor reconstitution. For analysis of short-term reconstitution, only thymus (for T-cell staining) and BM (for B and myeloid cell staining) were harvested, whereas for analysis of long-term reconstitution, thymus, BM, and spleens were harvested and stained (splenic data shown above). T, B, and myeloid cells were detected with the MoAbs: Thy1.2, B220, and MAC1, respectively. Donor reconstitution was evaluated using flow cytometry where the above tissues were stained with lineage specific MoAbs and the A20 MoAb that recognizes donor cells (Ly5.2+). Limit of detection of donor cells was 1%. Short-term and long-term reconstitution potential from PBMNC from FL-treated mice was performed in two separate experiments each giving similar results.

N = 2.

Long-term reconstitution was evaluated 6 months postirradiation. We harvested the BM, thymus, and spleen from each mouse for phenotypic analysis. Similar to the short-term reconstitution, there was virtually no reconstitution by donor cells in mice that received PBMNC from MSA-treated donor mice, although there was good donor reconstitution by donor cells in mice that received control BM cells (76%, 88%, and 74% donor reconstitution of T cell, B cell, and myeloid cells respectively). Mice reconstituted with high dose PBMNC (5 × 105 cells) from FL-treated mice also showed good long-term reconstitution similar to BM. However, mice reconstituted with low dose PBMNC (1 × 105 cells) from FL-treated mice showed significantly less donor reconstitution of T, B, and myeloid lineages when compared with BM (P = .0006, .0002, and .0007, respectively). Both high and low dose PBMNC from FL plus G-CSF–treated mice reconstituted all hematopoietic lineages with donor-derived cells when measured 6 months postirradiation. However, this reconstitution was significantly less than that from control BM cells P < .02). These data indicate that there is a lower frequency of long-term reconstituting cells in FL or FL plus G-CSF PBMNCs versus normal BM.

DISCUSSION

Growth factor-mobilized PBPC are being used increasingly in an attempt to shorten the duration of cytopenia following chemotherapy.1,30 In addition, using PBPC in place of BM is preferable where there is tumor involvement in the BM and in the allogeneic transplantation setting where there is a potential graft versus leukemia effect.31-33 However, transplantation using mobilized PB has its caveats.34 These include multiple rounds of apheresis necessary to collect the minimum number of CD34+ cells/CFU-GM required for rapid and sustained engraftment, and the chemotherapy-induced cytopenia that compromises the donor in the autologous setting, when mobilization is induced with growth factors plus chemotherapy. We have shown here that large numbers of CFU can be mobilized into the PB in 6 days (without the use of chemotherapy) using FL in combination with GM-CSF or G-CSF, and that this increase in CFU in PB is transient.

We compared the capacity of FL, G-CSF, and GM-CSF as single agents to increase WBC and mobilize CFU-GM and CFU-GEMM into the PB of C57BL/6 mice. We found that, on its own, human G-CSF gave only a weak increase in PB WBCs (twofold) and a modest increase in CFU-GM (30-fold). Recently, Roberts et al35 showed that G-CSF–induced mobilization of CFU is under genetic control and that the C57BL/6 strain of mice does not mobilize CFU-GM as well as the BALB/C or DBA/2 strains. The G-CSF–induced increase in WBC and mobilization of CFU we observed are similar to those described by Roberts et al35 in C57BL/6 mice. We, too, have compared the capacity of FL to increase WBC and mobilize CFU into the PB of various strains of mice (C57BL/6, BALB/C, DBA/2, and C3H/HeN) (data not shown). The maximal WBC counts were quite similar (approximately 15 × 106/mL) in all strains of mice after 10 days FL administration. However, there were approximately threefold more CFU-GM mobilized by FL into the PB of C3H/HeN, BALB/C, and DBA/2 strains of mice than in the C57BL/6 strain. Further studies will be necessary to determine whether mobilization induced by FL in different strains of mice is under the same genetic control as demonstrated for G-CSF.

We have previously demonstrated the effects on hematopoiesis when recombinant FL alone is administered to mice.26 In this report, we analyzed the capacity of FL, combined with G-CSF or GM-CSF, to mobilize CFU-GM and CFU-GEMM into the PB of mice. FL, synergized with G-CSF or GM-CSF, to increase the frequency of CFU in PB, and accelerated the kinetics of mobilization when compared with FL treatment alone (Fig 2A and B). Recently, two independent laboratories obtained similar results showing that FL synergized with G-CSF to increase WBCs and mobilize CFU-GM into the peripheral blood of normal mice.36 37 Our studies also showed that when FL was combined with G-CSF, there was a profound increase in WBCs (21-fold over control) that, when multiplied by the CFU frequency, resulted in a 1,423- and 2,717-fold increase in the absolute number of CFU-GM and CFU-GEMM per mL of blood, respectively.

The mechanism responsible for the increase in CFU in the PB is unknown, although the source of the CFU is most likely BM (see below). It is difficult to directly compare our mobilization results with FL against those obtained by other investigators who use different growth factor treatments because there is variability in experimental design (eg, the use of splenectomized mice, different mouse strains, different CFU-GM assays, etc). However, no growth factor combination that gives as large an increase for mobilized CFU in normal mice as does FL plus G-CSF has been reported (our data, Sudo,36 and Molineux37 ).

Our data showed a large increase in circulating CFU with growth factor treatment, and we also evaluated the effects of growth factor treatment on CFU in BM. Whereas GM-CSF or G-CSF had no significant effect on BM CFU after 5 to 7 days of treatment, FL alone, or in combination with GM-CSF or G-CSF, significantly increased CFU-GM and CFU-GEMM by as much as threefold and sixfold, respectively (Table 1). The initial increase in BM CFU (on days 1 and 3 of growth factor treatment) was due to FL alone. G-CSF, when combined with FL for 5 to 7 days, dramatically decreased BM CFU below control levels, and this is a likely source for elevated PB CFU 6 days after growth factor treatment. Similar results were recently shown.36 37

Although 1,000 R was not 100% lethal to our irradiation control mice, PBMNC from either FL-treated or FL plus G-CSF–treated mice afforded statistically significant enhanced protection from radiation (Fig 3). In addition, mobilized PBMNCs could reconstitute lymphoid and myeloid lineages in a dose-dependent manner 6 months postirradiation (Table 2), showing that primative multilineage progenitors were mobilized in addition to the less primitive CFU-GM.26 Recently, Molineux et al37 showed that E coli–derived FL plus G-CSF–mobilized PBPC protected mice from lethal irradiation and that donor cells persisted for up to 2 years postengraftment.37 Interestingly, their data indicated that administration of E coli–derived FL alone did not mobilize CFU-GM nor PBPC that could provide long-term engraftment. These data indicate the importance in evaluating dosing regimen and the form of FL used to mobilize PBPC. Because of the inactivity of yeast-derived–murine GM-CSF in mice to mobilize CFU in mice, experiments were done comparing FL plus human GM-CSF or FL plus human G-CSF to mobilize CFU in primates. These primate studies showed comparable mobilization of CD34+ cells with FL plus GM-CSF or G-CSF and synergy versus single growth factors.38 The data presented here suggests the potential use of FL, alone or in combination with GM-CSF or G-CSF, to mobilize large numbers of multilineage progenitor cells into the PB of humans.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Megan Webster for professional animal care and Anne Bannister for critically reviewing this manuscript.

Address reprint requests to Kenneth Brasel, Department of Immunobiology, Immunex Corp, 51 University St, Seattle, WA 98101.

![Fig. 1. Effects of growth factor administration on WBC numbers. Mice were injected SC with 1 μg MSA or MSA plus growth factor (each at 10 μg) daily for up to 10 days. Four mice per group were killed after 2, 4, 6, and 10 days growth factor treatment, as well as 7 days postcessation of treatment. The following symbols were used to represent each growth factor–treated group of mice: FL (•); G-CSF (▪); GM-CSF (▾); FL plus G-CSF (□); and FL plus GM-CSF (▿). The average WBC count in MSA control mice was 4.4 ± 1.7 × 106/mL blood. This experiment was performed twice giving very similar results (only differing in the route of injection [IP] and dosage of G-CSF and GM-CSF [5 μg/mouse/d]). Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM). WBC counts that differed significantly (P < .005) from MSA controls are marked (*).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/90/9/10.1182_blood.v90.9.3781/4/m_bl_0001f1.jpeg?Expires=1769249457&Signature=L9H~dLuYGRW-3UeN2FZdqyEgwXYZ0M0c04h6S3q8f28tjtd9y2aoQhyBF1m7N9xyXBkjXPRjQoWMRzus8a0TcgP8HW4EttBqtwpcs31Hs0Y~v-iFP8oJDkgsC0EvMpio5Y-YmT-jPY~HZdlyrTJcpYGuZAA29rS3pIUrlvojskiEOr-EB0-YUcemzJANJUiALb7mmllKySq7dqCSha9qzlSt8JZVJS11K-ZyOj74MEP~-vPUQFWfDuefTWB1FnAjmObS3Qalo8h6iYzltOqTA~U58BFcwSs-Vo56j-HGby2GLitN81-Om75hJFkp3JvS~XYJ94p3gX~am2JAOYf52A__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 2. Mobilization of CFU into the PB after growth factor administration. (A and B) The frequency of CFU-GM and CFU-GEMM (per 105 cells) in PB after 2, 4, 6, and 10 days growth factor treatment, respectively. (C and D) The absolute number of CFU-GM and CFU-GEMM per mL of PB (PBMNC count multiplied by CFU frequency) after 2, 4, 6, and 10 days growth factor treatment, respectively. PBMNC from four mice were pooled within each group for CFU assays (see Materials and Methods). In all growth factor-treated groups, total CFU per mL of PB and CFU frequency per 105 cells had almost returned to pretreatment values 1 week postgrowth factor treatment (data not shown). This experiment was performed twice giving very similar results (only differing in the route of injection [IP] and dosage of G-CSF and GM-CSF [5 μg/mouse/d]).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/90/9/10.1182_blood.v90.9.3781/4/m_bl_0001f2.jpeg?Expires=1769249457&Signature=YiX~fRpfWGT6yRuqFwb9JCZMQJ4a1OoErKY23bbGAiFktbq7Jg8RpNyOANluXKAF~pDJhdZAvcnOwajHC8tucWUfcUyrwQUp7mkjrVt-K~2ebfrv-5e0A~xEFIfMt~MfZPSwUFO4L48kGAmgrEuqJdvXB1YQLF4eH9rSiiMvdKiy1D8bJOBA9YIlPTQfL8uoDQZtOXuLx-dDGS~eGPHvdOA1mZe8TCC3y9khZtxfJb3UrofGVxs6ZvVNKIvje46XqrtgDHGEAhLXeVD2qYAp8YJu01ZmJ2hYTuD0-r-mN48URf91OdIJZYcJRq1mP2xN8G8cfAbn4WrowT6iAVKrOw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal