Abstract

It has previously been shown that human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) can be fused to a truncated diphtheria toxin (DT) to produce a recombinant fusion toxin that kills GM-CSF receptor–bearing cells. We now report that DT388–GM-CSF induces apoptosis and inhibition of colony formation in semisolid medium in receptor positive cells, and that the induction of apoptosis correlates with GM-CSF–receptor occupancy at low ligand concentrations. Also, the induction of apoptosis correlates with the inhibition of protein synthesis and is inversely related to the amount of intracellular antiapoptotic proteins (Bcl2 and Bc1XL ). Nine myeloid leukemia cells lines and four nonmyeloid leukemia cell lines were incubated with 0.7 nmol/L of 125I–GM-CSF in the presence or absence of excess cold GM-CSF and bound label measured. High affinity receptor numbers varied from 0 to 291 molecules per cell. Cells were incubated with varying concentrations of recombinant fusion toxin for 48 hours and incorporation of 3H-leucine (protein synthesis), segmentation of nuclei after DAPI staining (apoptosis), and colony formation in 0.2% agarose (clonogenicity) were measured. DT388–GM-CSF at 4 × 10−9 mol/L inhibited colony formation 1.5 to 3.0 logs for receptor positive cell lines. Protein synthesis and apoptosis IC50s varied among cell lines from greater than 4 × 10−9 mol/L to 3 × 10−13 mol/L. GM-CSF–receptor occupancy at 0.7 nmol/L GM-CSF–ligand concentration correlated with the protein synthesis IC50 . Similarly, the protein synthesis inhibition and apoptosis induction correlated well, except in cells overexpressing Bcl2 and BclXL , in which 25- to 150-fold inhibition of apoptosis was observed. We conclude that DT388–GM-CSF can kill acute myeloid leukemia blasts but that apoptotic sensitivities will depend on the presence of at least 100 high affinity GM-CSF receptors/cell and the absence of overexpressed antiapoptotic proteins.

ACUTE MYELOID leukemia (AML) was diagnosed in 9,200 patients in the United States in 1996,1 and even with complete remission rates of 50% to 70% and effective consolidation and intensification regimens including allogeneic bone marrow transplantation, over 80% of patients will die from complications of the disease or its treatment.2 Radiochemotherapy resistant blasts are a frequent cause of treatment failure in AML patients.3 In many cases, blasts exhibit a multidrug-resistance phenotype produced, in part, by overexpression of drug efflux transporters (P-glycoprotein and multidrug-resistance protein) or overexpression of antiapoptotic peptides (Bcl2 and BclXL ). Prospective and retrospective clinical studies have shown a worse prognosis for patients with resistance phenotypes caused by high concentrations of these molecules.4-7 Although nonspecific modulators of P-glycoprotein (quinine, cyclosporine, and PSC833) have been tested in AML therapy trials, to date these agents have been associated with significant toxicities to marrow and other organs, marked alterations of cytotoxic drug pharmacodynamics, and minimal effects on disease-free survival or overall survival.8 Thus, there is a need for new reagents with unique mechanisms of action that can selectively modify the apoptotic threshold of malignant blasts.

One such novel class of AML therapeutics is targeted toxin molecules. These polypeptide drugs consist of myeloid leukemia–directed ligands covalently linked to protein synthesis inactivating peptide toxins. We chose to use diphtheria toxin as the toxophore and human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) as the haptophore or ligand. Extensive experience both preclinically and clinically with diphtheria fusion toxins suggested this protein synthesis–inactivating peptide could efficiently kill malignant cells in vitro and in vivo.9 The ligand GM-CSF was chosen because the receptor for this cytokine is present on the majority of AML patients' blasts.10 The normal tissue distribution showed the presence of receptor on committed myeloid progenitor cells11 and alveolar macrophages,12 but not on primitive hematopoietic stem cells or other vital normal tissues.13 We prepared DT388–GM-CSF by modification of diphtheria toxin cDNA.14 Codons encoding DT amino acids 389 to 535 (the binding domain) were replaced with codons for human GM-CSF. We purified recombinant protein by refolding denatured and reduced inclusion body protein from Escherichia coli and showed potent selective protein synthesis inhibition of GM-CSF receptor–bearing cells. The fusion toxin intoxicates cells similarly to wild-type DT,15-19 except for binding to the GM-CSF receptor. DT388–GM-CSF is similar to DTctGM-CSF, which contains diphtheria toxin–amino acid residues 1 to 385 fused to a Ser-(Gly)4-Ser-Met linker to human GM-CSF.20 Both recombinant toxins showed better in vitro potency in killing leukemia blasts than other anti-AML–targeted toxins, including anti-CD33 antibody coupled with chemically blocked ricin,21 anti-CD33 antibody conjugated to gelonin,22 and GM-CSF fused to genetically modified ricin or Pseudomonas exotoxin.19,23 The greater efficiency of intoxication by the diphtheria fusion proteins may relate to their rapid escape to the cytosol from the endosomal compartment. Ricin, Pseudomonas exotoxin, and presumably gelonin must avoid lysosomal routing and reach a post-Golgi compartment before translocation to the cytosol.24

The goal of the present study was to determine the quantitative ability of DT–GM-CSF to induce apoptosis in myeloid leukemia cell lines. Because the ultimate clinical efficacy of an AML therapeutic depends on modulating the apoptotic threshold of leukemic progenitors rather than solely inhibiting protein synthesis, we believed such a study was a requisite step in the clinical development of the drug.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Characterization of DT388–GM-CSF.Protein, purified as described,19 was quantitated by BioRad protein assay as per recommendations of the supplier (BioRad, Hercules, CA). Aliquots of DT388–GM-CSF and prestained low molecular weight protein standards (BioRad) were run on a reducing 15% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and either stained with Coomassie Blue R-250 (Sigma Chemical Co, St Louis, MO) or transferred to nitrocellulose, blocked with 10% Carnation nonfat dry milk/0.1% bovine serum albumen (BSA)/0.1% Tween 20, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) plus 0.05% Tween 20, reacted with 5 μg/mL rabbit anti–GM-CSF (Genzyme, Cambridge, MA), rewashed, incubated with alkaline phosphatase conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Sigma), washed again, and developed with the Vectastain alkaline phosphatase kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) as per manufacturer's instructions. Gels and blots were scanned on an IBAS automatic image analysis system (Kontron, Germany).

DT388–GM-CSF binding affinity for the GM-CSF receptor was assayed by incubating 2 × 106 HL60 cells in 150 μL RPMI1640 plus 2.5% BSA (Sigma) plus 0.2% sodium azide (Sigma) plus 20 mmol/L HEPES (Sigma) pH 7.2 and different concentrations of yeast-derived GM-CSF (Immunex Corp, Seattle, WA) or DT388–GM-CSF. Finally, 5 μL containing 0.2 μCi radiolabeled 125I–GM-CSF (114 μCi/μg, 43 μCi/mL; DuPont, Wilmington, DE) were added to each tube and the tubes incubated at 37°C for 1 hour. Samples were then overlaid on 200 μL of phthalate oil mixture (1.5 parts dibutylphthalate and 1 part octylphthalate; Aldrich Chemical, Milwaukee, WI), centrifuged for 1 minute at 10,000 rpm in a microcentrifuge, and cell pellets and supernatants counted in a LKB-Wallach 1260 multi-gamma counter gated for 125I with 50% counting efficiency. Dissociation constant (kd) was calculated from Scatchard plots as the concentration of protein yielding 50% displacement of 125I-ligand.

Cell culture.HL60 and HL60/VCR human leukemia cells were obtained from Dr A. Safa25 and grown in RPMI1640 medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. All media and components were purchased from Irvine Scientific (Santa Ana, CA). HL60/Bcl2, HL60neo, and HL60/BclXL were isolated as previously described26 27 and maintained in RPMI1640 plus glutamine with 10% FBS with 1 mg/mL G418 (Geneticin, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). U937, K562, CEM, KB, HEL92.1.7, and THP-1 human leukemia cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD) and maintained on RPMI1640 medium plus glutamine with 10% FBS and penicillin/streptomycin. TF1 cells were obtained from Dr R. Puri (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) and grown on RPMI1640 plus glutamine with 10% FBS, 50 ng/mL human GM-CSF (Immunex), 1 mmol/L sodium pyruvate, and 1× nonessential amino acids. KG-1 and AML193 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. Both cell lines were grown in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium with 25 mmol/L HEPES and 10% FBS. The AML193 cells were supplemented with 50 ng/mL GM-CSF. The properties of the cell lines and their sources are described in Table 1.

Properties of Assayed Human Cell Lines

| Cell Line . | Description . | GM-CSF Dependence . | Reference . |

|---|---|---|---|

| HL60 | Acute myelogenous leukemia | − | 25 |

| HL60neo | HL60 with neo resistance | − | 26 |

| HL60/VCR | HL60 resistant to vincristine | − | 25 |

| HL60/Bcl2 | HL60 with Bcl2 transgene | − | 26 |

| HL60/BclXL | HL60 with BclXL transgene | − | 27 |

| K562 | Chronic myelogenous leukemia | − | 48 |

| KB | Mouth epidermoid carcinoma | − | 49 |

| CEM | T-lymphoblastic leukemia | − | 50 |

| HEL92.1.7 | Erythroleukemia | − | 51 |

| TF1 | Erythroleukemia | + | 52 |

| U937 | Monocytic leukemia | − | 53 |

| THP-1 | Acute monocytic leukemia | − | 54 |

| KG-1 | Acute myelogenous leukemia | − | 55 |

| AML193 | Acute monocytic leukemia | + | 56 |

| LS174T | Colon carcinoma | − | 57 |

| Cell Line . | Description . | GM-CSF Dependence . | Reference . |

|---|---|---|---|

| HL60 | Acute myelogenous leukemia | − | 25 |

| HL60neo | HL60 with neo resistance | − | 26 |

| HL60/VCR | HL60 resistant to vincristine | − | 25 |

| HL60/Bcl2 | HL60 with Bcl2 transgene | − | 26 |

| HL60/BclXL | HL60 with BclXL transgene | − | 27 |

| K562 | Chronic myelogenous leukemia | − | 48 |

| KB | Mouth epidermoid carcinoma | − | 49 |

| CEM | T-lymphoblastic leukemia | − | 50 |

| HEL92.1.7 | Erythroleukemia | − | 51 |

| TF1 | Erythroleukemia | + | 52 |

| U937 | Monocytic leukemia | − | 53 |

| THP-1 | Acute monocytic leukemia | − | 54 |

| KG-1 | Acute myelogenous leukemia | − | 55 |

| AML193 | Acute monocytic leukemia | + | 56 |

| LS174T | Colon carcinoma | − | 57 |

GM-CSF–receptor density.One to 12 million cells in RPMI1640 plus 2.5% BSA plus 0.2% sodium azide plus 20 mmol/L HEPES pH 7.2 in a total volume of 150 μL were incubated with 5 μL of 125I–GM-CSF (114 μCi/μg, 43 μCi/mL) in the presence or absence of 1,500 ng unlabeled human GM-CSF for 1 hour at 37°C. The cell suspensions were then layered on 200-μL phthalate oil mixture (1.5 parts dibutylphthalate and 1 part dioctylphthalate) in 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes, centrifuged at 10,000 rpm in a microfuge at room temperature for 1 minute, and the cell pellets counted in gamma counter with 50% efficiency as above. Counts per minute bound in the presence of cold GM-CSF were subtracted from total counts per minute and receptor occupancy calculated based on 4 × 10−6 cpm/bound molecule and the total number of cells. Because 2 ng of labeled GM-CSF representing 1 × 10−13 moles was diluted in 150 μL, the ligand concentration was 7 × 10−10 mol/L and the kd for GM-CSF on HL60 receptors was 1 × 10−10 mol/L,23 liquid concentration was sevenfold above the 50% dissociation concentration for high affinity receptors. Further, using an average of 5 × 106 cells and 200 receptors/cell, a 60-fold excess of ligand over receptor was obtained. Increasing the labeled ligand concentration yields higher receptor occupancy for low affinity receptors (kd = 1 to 2 × 10−9 mol/L).19

Bcl2 content of cells.Thirty-five–millimeter Costar dishes were incubated with 2 mL of 1-mg/mL polylysine (Sigma) in PBS for 15 minutes at 37°C then rinsed three times with PBS. Two hundred thousand cells in 2 mL serum-free medium were then placed in the dishes and centrifuged at 2,400 rpm for 10 minutes in a low-speed centrifuge without a brake. The media was discarded and the dishes washed three times with PBS and fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde (10% formalin) in PBS for 10 minutes at room temperature. The dishes were rinsed again with PBS and blocked with 1% BSA (Sigma)/0.1% saponin (Sigma) in PBS for 15 minutes. All reactions were performed at room temperature. The blocking solution was removed and monoclonal antibody 124 anti-Bcl2 (Dako, Carpinteria, CA) at 10 μg/mL in 1% BSA/.01% saponin/PBS was reacted with the cells for 30 minutes. Again the cells were rinsed three times with PBS, and goat anti-mouse Ig conjugated to rhodamine (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) was incubated with the cells for 30 minutes. The dishes were rinsed again three times with PBS and postfixed 10 minutes with 3.7% formaldehyde in PBS and mounted in glycerol to PBS (90:10) and examined using a Zeiss Axioplan epifluorescence microscope.

Protein synthesis inhibition assays.Twelve different concentrations of DT388–GM-CSF (4 × 10−9 mol/L to 1.7 × 10−13 mol/L) were incubated with 1.5 × 104 cells in Costar 96 well flat-bottomed plates in a total volume of 150 μL of media used for cell growth for 48 hours at 37°C/5% CO2 . All assays were performed in duplicate. Fifty microliters of media containing 1 μCi 3H-leucine was then added to each well and incubation at 37°C/5% CO2 continued for an additional 4 hours. Cells were then obtained on a Skatron Cell Harvestor onto glass fiber mats and 3H counts per minute counted in an LKB liquid scintillation counter gated for 3H. The calculated IC50 was the concentration of protein that inhibited protein synthesis by 50% compared with control wells without DT388–GM-CSF.

Apoptosis assays.Aliquots of 1 × 105 cells were incubated in 24-well Costar plates at 37°C/5% CO2 for 48 hours in media with 10 different concentrations of DT388–GM-CSF. Cells were then bound to polylysine-coated 35-mm dishes as described above, fixed in methanol containing 1 μg/mL DAPI (Sigma) to label nuclear DNA, and the percent apoptotic cells was determined by evaluating nuclear morphology by epifluorescence microscopy. The IC50 was the concentration of protein-inducing apoptosis in 50% of cells. Measurement of nuclear fragmentation for apoptosis using DAPI staining has been previously described.28

Clonogenic assay.Aliquots of 1 × 105 cells were incubated in wells of Costar 24-well plates at 37°C/5% CO2 in 1 mL RPMI 1640 plus 15% FCS for 48 hours with 10 different concentrations of DT388–GM-CSF. Cell aliquot (0.1 mL) containing 1 × 104 cells was then dispersed in 3.4 mL RPMI 1640 plus 15% FCS with 50 ng/mL interleukin-3 (IL-3; PharMingen), GM-CSF and G-CSF (Amgen), and 0.2% agarose (SeaPlaque; FMC BioProducts, Rockland, ME) in 35-mm gridded polystyrene petri dishes. After 20 minutes solidification at 4°C, dishes were incubated 7 to 12 days at 37°C/5% CO2 in a humidified incubator. Colonies containing more than 20 cells were counted on an inverted microscope.

RESULTS

Our goal is to develop DT388–GM-CSF for therapy of drug-resistant AML. For the rational design of clinical trials, we must define the variables that affect sensitivity of AML blasts to the drug. In this study, we have examined the effects of cell surface GM-CSF–receptor density and intracellular concentrations of antiapoptotic proteins on the induction of apoptosis by DT388–GM-CSF.

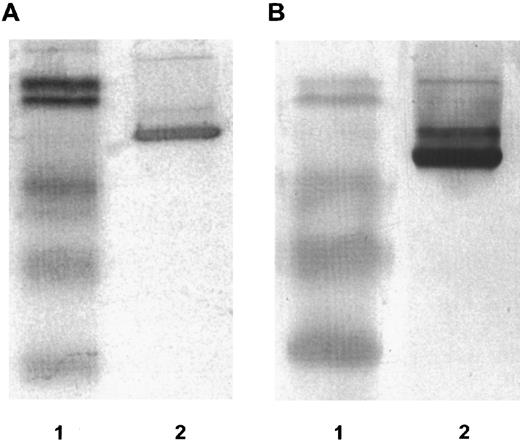

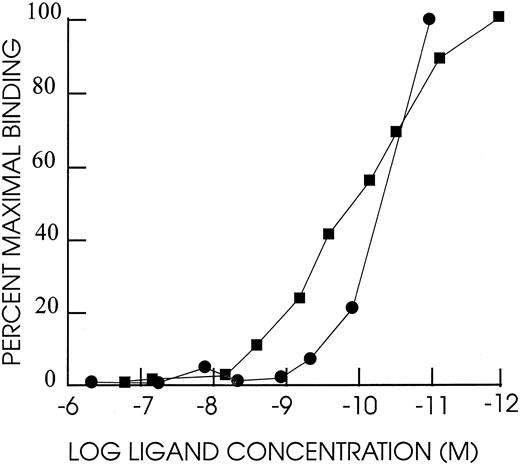

DT388–GM-CSF properties.Purified recombinant protein assayed colorimetrically yielded 800 μg/mL. Densitometry of Coomassie-stained gels and immunoblots using anti–GM-CSF antibody showed a single detectable band at 60 kD molecular weight (Fig 1). The affinity of DT388–GM-CSF for GM-CSF receptor was 1.4 × 10−10 mol/L compared with 1.0 × 10−10 mol/L for GM-CSF alone (Fig 2).

Fifteen percent reducing SDS-PAGE. (A) Coomassie stained. (B) Immunoblot reacted with rabbit anti-human GM-CSF antibody. Lanes in (A) and (B): lane 1, low molecular weight prestained BioRad protein standards with molecular weights 101 kD, 83 kD, 51 kD, 36 kD, and 29 kD; lane 2, DT388–GM-CSF.

Fifteen percent reducing SDS-PAGE. (A) Coomassie stained. (B) Immunoblot reacted with rabbit anti-human GM-CSF antibody. Lanes in (A) and (B): lane 1, low molecular weight prestained BioRad protein standards with molecular weights 101 kD, 83 kD, 51 kD, 36 kD, and 29 kD; lane 2, DT388–GM-CSF.

Competition binding experiment with HL60 cells. A total of 2 × 106 cells mixed with different concentrations of human GM-CSF or DT388–GM-CSF and 0.2 μCi 125I–labeled GM-CSF in 150 μL RPMI1640 with 2.5% BSA and 0.2% sodium azide and 20 mmol/L HEPES pH 7.2 and incubated for 1 hour at 37°C. Cells were centrifuged through a phthalate oil mixture and free and bound counts per minute determined. Scatchard analysis was used to determine kds.

Competition binding experiment with HL60 cells. A total of 2 × 106 cells mixed with different concentrations of human GM-CSF or DT388–GM-CSF and 0.2 μCi 125I–labeled GM-CSF in 150 μL RPMI1640 with 2.5% BSA and 0.2% sodium azide and 20 mmol/L HEPES pH 7.2 and incubated for 1 hour at 37°C. Cells were centrifuged through a phthalate oil mixture and free and bound counts per minute determined. Scatchard analysis was used to determine kds.

Distribution of GM-CSF receptor on cell lines.We measured GM-CSF receptor occupancy at 0.7 nmol/L ligand by incubating cells with radiolabeled ligand and determining the bound number of molecules. Using this method, reproducible receptor occupancies were obtained (Table 2). For myeloid blasts requiring GM-CSF in their growth media (TF1 and AML193), prewashing with medium lacking growth factor was critical for accurate assay. Receptor occupancy varied from 0/cell for K562, CEM, and HEL92.1.7 to 291/cell for THP-1. Low affinity sites/cell for U937, HL60, and TF1 were reported to be 3,500, 540, and 3,700 sites/cell, respectively.19

GM-CSF–Receptor Occupancy at 0.7 nm Ligand for Assayed Cell Lines

| Cell Line . | Receptors Occupied/Cell . |

|---|---|

| THP-1 | 291 |

| KB | 272 |

| HL60neo | 195 |

| U937 | 178 |

| TF1 | 165 |

| HL60/VCR | 158 |

| HL60 | 156 |

| HL60Bcl2 | 156 |

| KG1 | 136 |

| HL60BclXL | 119 |

| AML193 | 80 |

| LS174T | 42 |

| HEL92.1.7 | 0 |

| K562 | 0 |

| CEM | 0 |

| Cell Line . | Receptors Occupied/Cell . |

|---|---|

| THP-1 | 291 |

| KB | 272 |

| HL60neo | 195 |

| U937 | 178 |

| TF1 | 165 |

| HL60/VCR | 158 |

| HL60 | 156 |

| HL60Bcl2 | 156 |

| KG1 | 136 |

| HL60BclXL | 119 |

| AML193 | 80 |

| LS174T | 42 |

| HEL92.1.7 | 0 |

| K562 | 0 |

| CEM | 0 |

Assay performed in duplicate as described in text. Values are means.

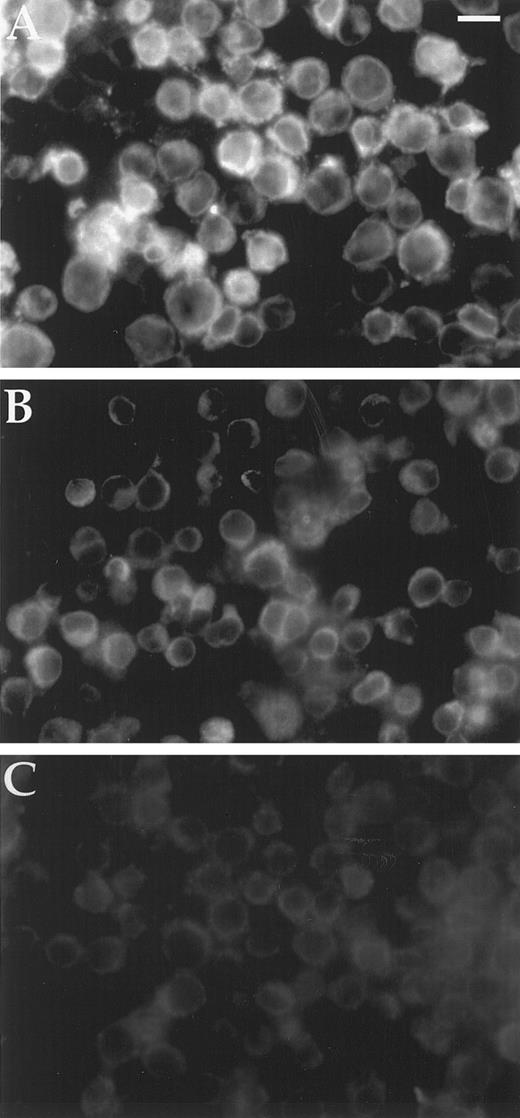

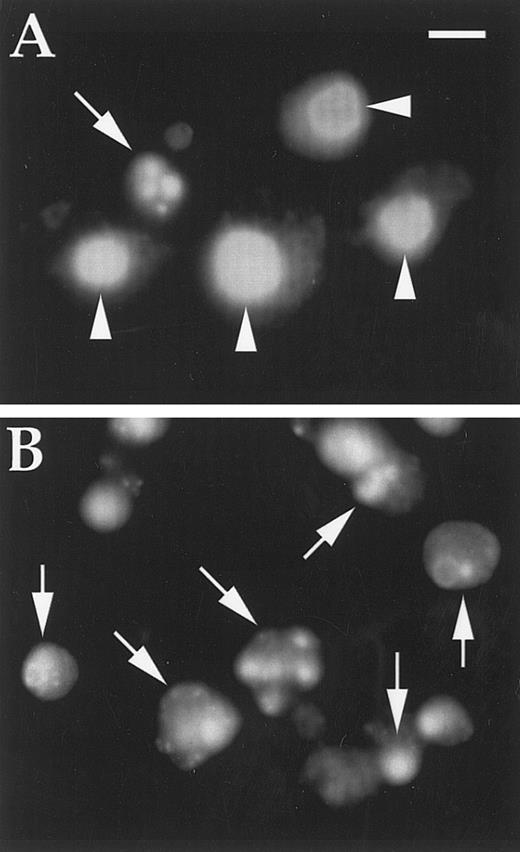

Bcl2 content of cell lines.Background fluorescence intensity for Bcl2 detection was 5 mU from the Zeiss Axioplan photometer average of five single cells for HL60Bcl2 without primary antibody. HL60, HL60BclXL, TF1, and HEL92.1.7 yielded the same 5 mU of Bcl2 immunofluorescence. In contrast, HL60Bcl2 produced 16 mU and HL60/VCR showed 8 mU (Fig 3). The cell-to-cell variation in fluorescence intensity was less than 1 mU for all cell lines except HL60Bcl2, which showed a range of 11.7 to 18.8 mU with a standard deviation of 1.4 mU.

Immunofluorescence assay of cellular Bcl2. Two hundred thousand cells bound to polylysine-coated 35-mm Costar dishes were washed with PBS and fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde in PBS, rinsed again with PBS, blocked with 1% BSA/0.1% saponin, and reacted with monoclonal anti-Bcl2 antibody in 1% BSA/0.1% saponin/PBS. Cells were again rinsed with PBS and bound antibody detected with rhodamine conjugated goat anti-mouse Ig. After a final rinse with PBS and postfixing in 3.7% formaldehyde, dishes were mounted in glycerol:PBS and examined under a Zeiss Axioplan epifluorescence microscope. Magnification is × 350; scale bar represents 17 μm. (A) HL60; (B) HL60/VCR; (C) HL60BclXL .

Immunofluorescence assay of cellular Bcl2. Two hundred thousand cells bound to polylysine-coated 35-mm Costar dishes were washed with PBS and fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde in PBS, rinsed again with PBS, blocked with 1% BSA/0.1% saponin, and reacted with monoclonal anti-Bcl2 antibody in 1% BSA/0.1% saponin/PBS. Cells were again rinsed with PBS and bound antibody detected with rhodamine conjugated goat anti-mouse Ig. After a final rinse with PBS and postfixing in 3.7% formaldehyde, dishes were mounted in glycerol:PBS and examined under a Zeiss Axioplan epifluorescence microscope. Magnification is × 350; scale bar represents 17 μm. (A) HL60; (B) HL60/VCR; (C) HL60BclXL .

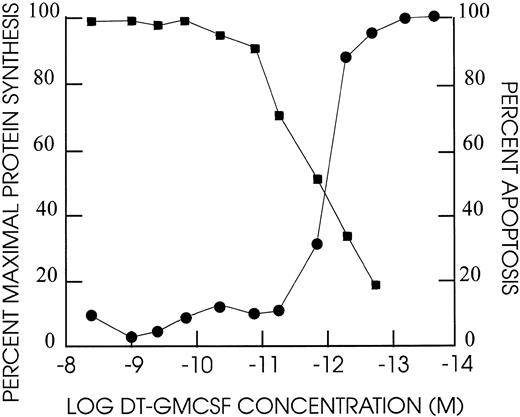

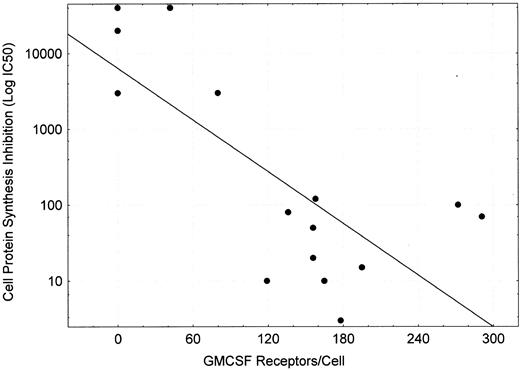

Protein synthesis inhibition of cell lines by DT388–GM-CSF.DT388–GM-CSF at 4 × 10−9 mol/L produced greater than 90% inhibition of protein synthesis of all cell lines except CEM, HEL92.1.7, K562, and LS174T (Fig 4 and Table 3). The IC50s varied for the remaining cell lines varied from 3 × 10−10 mol/L for AML193 to 3 × 10−13 mol/L for U937. Linear regression analysis showed correlation between high affinity GM-CSF–receptor density (receptor occupancy at 0.7 nmol/L) and protein synthesis–inhibition sensitivity to DT388–GM-CSF (Fig 5, r2 = .56).

Cell cytotoxicity of DT388–GM-CSF on TF1 human leukemia cells. Cells were exposed at the dilutions indicated for 48 hours at 37°C/5% CO2 . Incorporation of 3H-leucine was assayed after an additional 4 hours incubation and compared against untreated cell incorporation. The percent apoptotic nuclei based on DAPI staining were determined after 48 hours for different dilutions of DT388-GMCSF. (•) % maximal protein synthesis; (▪) % apoptosis.

Cell cytotoxicity of DT388–GM-CSF on TF1 human leukemia cells. Cells were exposed at the dilutions indicated for 48 hours at 37°C/5% CO2 . Incorporation of 3H-leucine was assayed after an additional 4 hours incubation and compared against untreated cell incorporation. The percent apoptotic nuclei based on DAPI staining were determined after 48 hours for different dilutions of DT388-GMCSF. (•) % maximal protein synthesis; (▪) % apoptosis.

Sensitivity of Cell Lines to Protein Synthesis Inhibition by DT388–GM-CSF

| Cell Line . | IC50 (×10−13 mol/L) . |

|---|---|

| U937 | 3 |

| HL60BclXL | 10 |

| TF1 | 10 |

| HL60neo | 15 |

| HL60Bcl2 | 20 |

| HL60 | 50 |

| THP-1 | 70 |

| KG1 | 80 |

| KB | 100 |

| HL60/VCR | 120 |

| AML193 | 3,000 |

| K562 | 3,000 |

| CEM | 20,000 |

| HEL92.1.7 | >40,000 |

| LS174T | >40,000 |

| Cell Line . | IC50 (×10−13 mol/L) . |

|---|---|

| U937 | 3 |

| HL60BclXL | 10 |

| TF1 | 10 |

| HL60neo | 15 |

| HL60Bcl2 | 20 |

| HL60 | 50 |

| THP-1 | 70 |

| KG1 | 80 |

| KB | 100 |

| HL60/VCR | 120 |

| AML193 | 3,000 |

| K562 | 3,000 |

| CEM | 20,000 |

| HEL92.1.7 | >40,000 |

| LS174T | >40,000 |

Assays performed in triplicate and mean values displayed as described in text.

Plot of GMCSF receptors/cell (measured at ligand concentration of 0.7 nmol/L) versus IC50 for DT388–GM-CSF (concentration of drug inhibiting cell protein synthesis by 50%). Linear regression performed yielded log (IC50 ) = 0.11*(GM-CSF receptor occupancy at 0.7 nmol/L) + 3.806 with r2 = .557.

Plot of GMCSF receptors/cell (measured at ligand concentration of 0.7 nmol/L) versus IC50 for DT388–GM-CSF (concentration of drug inhibiting cell protein synthesis by 50%). Linear regression performed yielded log (IC50 ) = 0.11*(GM-CSF receptor occupancy at 0.7 nmol/L) + 3.806 with r2 = .557.

Apoptosis induction of cell lines by DT388–GM-CSF.All DT388–GM-CSF–sensitive cell lines showed morphological evidence of apoptotic nuclear segmentation (Fig 6). Concentrations of DT388–GM-CSF produced 50% apoptosis after 48 hours incubation (IC50 ) as shown in Table 4. IC50 for apoptosis correlated well with IC50 for protein synthesis inhibition (ratios, 1 to 3), except for the three cell lines with overexpression of Bcl2 (HL60Bcl2 and HL60/VCR) or BclXL (HL60BclXL ). In these three cell lines, much higher concentrations of DT388–GM-CSF (25- to 150-fold) were required to achieve the same degree of apoptosis.

DAPI-stained cells treated with DT388–GM-CSF as described in text. (A) K562 cells (one apoptotic cell); (B) U937 cells (all apoptotic cells). Magnification is × 600; scale bar represents 10 μm; arrows indicate apoptotic nuclei; arrowheads indicate normal nuclei.

DAPI-stained cells treated with DT388–GM-CSF as described in text. (A) K562 cells (one apoptotic cell); (B) U937 cells (all apoptotic cells). Magnification is × 600; scale bar represents 10 μm; arrows indicate apoptotic nuclei; arrowheads indicate normal nuclei.

Apoptotic Threshold for Cell Lines Exposed to DT388–GM-CSF

| Cell Line . | IC50 (1 × 10−13 mol/L) . | Ratio PSI IC50 /Apopt.IC50 . |

|---|---|---|

| U937 | 10 | 3 |

| TF1 | 20 | 2 |

| HL60neo | 50 | 3 |

| HL60 | 50 | 1 |

| KG1 | 80 | 1 |

| HL60Bcl2 | 500 | 25 |

| THP-1 | 240 | 3.5 |

| HL60BclXL | 1,500 | 150 |

| HL60/VCR | 4,000 | 30 |

| AML193 | 4,000 | 1.3 |

| CEM | >40,000 | ND |

| HEL92.1.7 | >40,000 | ND |

| Cell Line . | IC50 (1 × 10−13 mol/L) . | Ratio PSI IC50 /Apopt.IC50 . |

|---|---|---|

| U937 | 10 | 3 |

| TF1 | 20 | 2 |

| HL60neo | 50 | 3 |

| HL60 | 50 | 1 |

| KG1 | 80 | 1 |

| HL60Bcl2 | 500 | 25 |

| THP-1 | 240 | 3.5 |

| HL60BclXL | 1,500 | 150 |

| HL60/VCR | 4,000 | 30 |

| AML193 | 4,000 | 1.3 |

| CEM | >40,000 | ND |

| HEL92.1.7 | >40,000 | ND |

Assays performed as described in text on at least two separate times. The cell line data were divided into two groups: those with and without elevated anti-apoptotic protein concentrations. A contingency table was then established using ratios less than 4 and greater than or equal to 4. Using Fisher's exact test the probability of a result as extreme as observed under the null hypothesis that elevated and nonelevated ratios come from the same population is less than 0.01.

Abbreviation: ND, not determined.

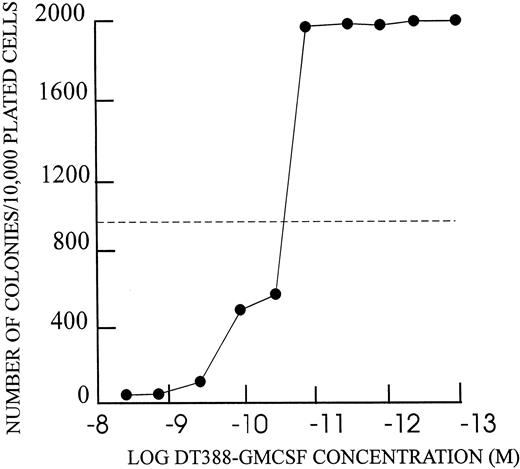

Inhibition of colony formation by DT388–GM-CSF.Each of the DT–GM-CSF–sensitive cell lines showed inhibition of colony formation in agarose (Fig 7 and Table 5). Maximal concentrations of DT388–GM-CSF (4 × 10−9 mol/L) yielded 1.5 to 3.0 log reduction in colony number in each case. The IC50s for colony inhibition were similar to those for apoptosis and protein synthesis inhibition.

Colony formation inhibition by DT388–GM-CSF as described in text. Number of colonies with greater than 50 cells at 14 days from 104 cells shown on Y-axis. DT388–GM-CSF concentration for 48 hour preincubation shown on X-axis.

Colony formation inhibition by DT388–GM-CSF as described in text. Number of colonies with greater than 50 cells at 14 days from 104 cells shown on Y-axis. DT388–GM-CSF concentration for 48 hour preincubation shown on X-axis.

Colony Formation for Cell Lines Reacted With DT388–GM-CSF

| Cell Line . | Maximal Log Cell Kill . | IC50 (×10−12 mol/L) . |

|---|---|---|

| U937 | 3.5 | 1 |

| HL60neo | 2.0 | 10 |

| AML193 | 2.5 | 10 |

| HL60 | 3.0 | 20 |

| KG1 | 2.0 | 20 |

| THP-1 | 1.8 | 20 |

| HL60BclXL | 1.5 | 40 |

| HL60VCR | 2.5 | 40 |

| HL60Bcl2 | 2.6 | 40 |

| K562 | 0 | >4,000 |

| CEM | 0 | >4,000 |

| HEL92.1.7 | 0 | >4,000 |

| Cell Line . | Maximal Log Cell Kill . | IC50 (×10−12 mol/L) . |

|---|---|---|

| U937 | 3.5 | 1 |

| HL60neo | 2.0 | 10 |

| AML193 | 2.5 | 10 |

| HL60 | 3.0 | 20 |

| KG1 | 2.0 | 20 |

| THP-1 | 1.8 | 20 |

| HL60BclXL | 1.5 | 40 |

| HL60VCR | 2.5 | 40 |

| HL60Bcl2 | 2.6 | 40 |

| K562 | 0 | >4,000 |

| CEM | 0 | >4,000 |

| HEL92.1.7 | 0 | >4,000 |

Assay performed as described in text at least twice.

DISCUSSION

The bacteria-derived recombinant fusion toxin DT388–GM-CSF was soluble, had the molecular weight predicted for the 515 amino acid sequence, and showed immunoreactivity with anti–GM-CSF antibody. Gel electrophoresis showed the protein purity was greater than or equal to 95%. The DT388–GM-CSF had better affinity for the GM-CSF receptor than GM-CSF–ricin by 1.8-fold.23 The crystal structure of GMCSF,29 mutational analysis,30 and blocking monoclonal antibody studies31 previously showed that the cytokine is a member of the four helix bundle family and the ligand interacts with receptor with the principal amino acid residues clustered midway along helices A and C and with some residues at the C-terminus. Thus, attachment of GM-CSF to the C-terminus of DT avoiding steric blockage of both the middle and C-terminus of GM-CSF would be expected to yield the best affinity with receptor. Further, x-ray crystal structure of DT shows amino acid residues 380 to 388 are separate from the translocation domain and permit extensive freedom of movement for the C-terminal domain.16 This linker sequence should provide more flexibility than the ADP tripeptide used to link GM-CSF and ricin.

The assay we used to quantitate GM-CSF receptor density used an intermediate concentration of radiolabeled GM-CSF that was sevenfold higher than the kd of the high affinity receptor and twofold less than the kd of the low affinity receptor.32 Thus, we measured the high affinity receptors (ligand occupancy of more than 90% for high affinity receptor) and a fraction (<20%) of the low affinity receptors. The high affinity receptors have been shown to be heterodimers of α and β subunits, whereas the low affinity receptors consist of α subunits alone.33 The low to absent number of high affinity receptors on non-AML cell lines agrees with previous observations.34,35 The presence of high affinity receptors on AML cell lines that are not dependent on exogenous GM-CSF has been previously documented10 and may be caused by autocrine production of GM-CSF36 or hyperphosphorylation of raf-1, an intermediate in the GM-CSF signal-transduction pathway.37

Bcl2 measurements yielded a positive signal on HL60/VCR cells not previously reported. Because these cells were selected by chronic exposure to 1 μg/mL vincristine,25 they may overexpress a number of multidrug-resistance proteins such as bcl2, in addition to their known overexpression of P-glycoprotein. A similar selection process showed overexpression of a number of resistance genes in MCF7 cells grown in the presence of adriamycin.38

Protein synthesis inhibition by DT388–GM-CSF was observed only for cell lines showing greater than 100 high affinity receptors/cell. Dependence of fusion toxin sensitivity on expression of high affinity receptors has been documented for DAB389IL-2.39 Because internalization is a prerequisite for DT intoxication,18 and only high affinity α/β-receptors will mediate receptor-mediated endocytosis,40 these results are consistent with molecular models of DT fusion protein action. The low number of receptors necessary for effective DT intoxication has been previously observed for DAB389IL-2 and native DT.17,39 Most normal tissues, except for normal myeloid progenitors,13 pulmonary alveolar macrophages,12 and possibly some endothelial cells,41 lack high affinity GM-CSF receptors. Systemic administration of DT388–GM-CSF should produce transient myelosuppression, may affect pulmonary antimicrobial defenses, and may yield tissue-specific vascular leak. Upregulation of high affinity GM-CSF receptors on leukemic blasts may be possible with infusions of interferon-γ.42

Induction of apoptosis by DT–GM-CSF has been reported for sensitive and drug resistant AML cells.20 However, quantitative sensitivities to apoptosis induction have not been previously reported. The current study showed a close correlation between protein synthesis inhibition and apoptotic threshold, except for cells overexpressing the antiapoptotic proteins bcl2 and bclXL . These results imply a critical role for reduction in new protein synthesis for triggering apoptosis and the use of this highly conserved (similar to the ced9 pathway in Chlamydia elegans) apoptosis pathway by diphtheria toxin.43 Targeting the antiapoptotic peptide with antisense oligothionucleotides to Bcl2 or BclXL may facilitate AML killing with DT388–GM-CSF.44

Clonogenic assays in semisolid medium have been used to assess progenitor blast viability45 and was used in this work to confirm the observations of protein synthesis inhibition and apoptosis induction. The results show selective toxicity of DT388–GM-CSF for clonogenic receptor positive cell lines.

These results also have pertinence to the clinical development of DT–GM-CSF. In particular, patients with greater than 100 high affinity GM-CSF receptors/blast and with lack of expression of bcl2 and bclXL will likely benefit from DT–GM-CSF therapy. However, extension from cell line studies to activity on fresh leukemic cells should be viewed with caution as, in several cases, targeted toxins perform better on cell lines than fresh leukemic cells.46 47 Confirmatory clonogenic assays on fresh AML blasts will be needed to confirm the findings reported with established hematopoietic cell lines.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jim Nicholson for photography and graphic analysis and Dr Alan J. Gross of the Department of Biometry and Epidemiology, Medical University of South Carolina for statistical analyses. We also acknowledge the use of the GCRC statistical services.

Supported by an institutional grant from the Medical University of South Carolina (A.F.).

Address reprint requests to Arthur E. Frankel, MD, Hollings Cancer Center Room 311, 86 Jonathan Lucas St, Charleston, SC 29401.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal