Abstract

The concept of tumor suppression by tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases (TIMPs) has evolved primarily from studies of genetically modulated tumor cells. The next step is to focus on the host and assess the protective potential of host TIMP-1 on primary tumor growth and metastasis. We generated two transgenic mouse lines with altered Timp-1 expression in skin and liver: one overexpressed Timp-1 (Timp-1high), and the other had antisense RNA–mediated Timp-1 reduction (Timp-1low). ESbL-lacZ T-lymphoma cells provided the tumor challenge, as they form primary tumors upon intradermal injection with spontaneous metastasis to liver. Metastases were examined in X-Gal–stained whole-organ mounts. Timp-1 overexpression inhibited intradermal tumor growth and spontaneous metastasis, leading to prolonged survival of the mice. The opposite effects occurred in Timp-1low mice, leading to shorter host survival. Experimental metastasis assays showed that Timp-1–compromised livers in Timp-1low mice showed at least a doubling of metastatic foci and numerous additional micrometastases, indicative of increased host susceptibility. However, Timp-1high mouse livers showed an unaltered metastatic load in the experimental metastasis assay. In conclusion, these data demonstrate that Timp-1 levels within a tissue predetermine the development and progression of T-cell lymphoma.

THE HOST CONTRIBUTES to cancer progression by providing an environment that constantly interacts with the tumor cells and either mediates or suppresses their survival, proliferation, and colonization. This includes a specific immune response mediated by T cells,1 nonspecific immune responses mediated by natural killer cells2 and macrophages,3 or production of cytokines and nitric oxide by endothelial cells.4 A noncellular host defense especially relevant to the formation of metastases is the structural barrier of the extracellular matrix (ECM). Increased clinical aggressiveness of lymphoma is associated with increased ECM catabolism5 resulting from high proteinase and low proteinase inhibitor levels, and it has been shown that the composition of ECM in malignant lymphomas differs in low- versus high-grade tumors.5-7

Members of the matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) family are essential for ECM degradation,8 and their activity is regulated by tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs). Of the four murine Timp genes reported to date,9Timp-1 was the first to be identified and has served as a prototype for their role in tumor growth and metastasis. We have previously shown that downregulation of Timp-1 by antisense mRNA in murine fibroblasts imposed tumorigenic and metastatic behavior,10 whereas injection of recombinant TIMP-1 protein11,12 or synthetic metalloproteinase inhibitors13 was shown by others to significantly reduce experimental metastasis. Further, we recently reported that the initiation and progression of viral T-antigen–induced hepatocellular carcinoma in a transgenic mouse model was suppressed with elevated hepatic Timp-1 levels.14 These distinct experimental approaches have demonstrated the tumor-suppressive effects of Timp-1. Nevertheless, the effect of tissue-specific alteration of host Timp-1 on metastasis, the ultimate cause of mortality for most tumor types, is not known.

Normal lymphoid cells have an intrinsic ability to adopt invasive behavior to access every site in the body, and this likely accounts for the high aggressiveness of one of their transformed descendants, namely the lymphomas.15 High expression of TIMP-1 mRNA has been localized to stromal cells of endothelial and fibroblastic origin in high-grade advanced-stage non-Hodgkin's lymphomas.6,16,17 Currently, it remains unknown whether expression of TIMP-1 is a host defense response or a promoter of lymphoma malignancy. This question cannot be answered using clinical specimens that are often only accessible from later stages of the disease. We developed a mouse model to investigate whether modulated host Timp-1 levels would affect the primary tumor growth of a T-cell lymphoma in the skin and its subsequent metastasis in the liver. lacZ-tagged T-lymphoma cells (ESbL-lacZ) that spontaneously metastasize from an intradermal site mainly to the liver allowed high-resolution analysis of metastasis,18 while genetically modulated Timp-1 transgenic hosts14 were the recipients of the tumor challenge. We found that modulation of Timp-1 within the skin affected the intradermal primary tumor growth and that Timp-1 modulation in the liver directly impacted the colonization of T-cell lymphoma. These data demonstrate that Timp-1 levels within a tissue predetermine the development and progression of T-cell lymphoma.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Transgenic mice.We have previously described the C57BL/6-derived Timp-1 transgenic mice.14 Briefly, the mouse line Ts-4 produces transgenic Timp-1 mRNA and line Ta-1 produces antisense Timp-1 RNA from a constitutive murine major histocompatibility complex class I (H2) promoter, resulting in either an augmentation or a reduction of endogenous Timp-1 protein levels in the respective lines.14 For the studies described here, Timp-1 transgenic mice (C57BL/6) were backcrossed once in DBA/2 background, which is syngeneic to the ESbL lymphoma. ESbL primary tumor take, spontaneous metastasis, and the number of experimental liver metastases in F1 of C57BL/6xDBA/2 were similar as reported for DBA/2 background. Ts-4/DBA backcrosses were designated as Timp-1high and Ta-1/DBA as Timp-1low. Hemizygous litters were genotyped by Southern analysis of DNA prepared from tail tissue, and experiments were performed when mice were 6 weeks of age. Littermates were categorized as negative wild-type control or transgene-positive mice, depending on the absence or presence of the Timp-1 transgene.

Cell lines.ESbL-lacZ T-lymphoma cells are a subline of L-CI.5s cells that had been transduced with the bacterial lacZ gene and were maintained as previously described.18 19

Injection of tumor cells.For intradermal injections, 5 × 103 cells (or 5 × 104 for the rechallenge) were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and inoculated in the cutis of the shaved flank of anesthesized mice (Rompun 0.1%; Miles, Mississauga, Canada: Ketanest 0.25%; MTC Pharmaceuticals, Cambridge, Canada: PBS 1:1:3 vol/vol). Tumor diameters were measured with a caliper. Moribund mice were killed according to the regulations of the Canadian Council on Animal Care, and were counted as dead in the assessment of the survival curves. For experimental metastasis, 1 × 105 cells in 200 μL PBS were injected into the tail vein.

RNA isolation and Northern analysis. Timp-1 mRNA levels were assessed in the skin or liver tissue. The skin was shaved to remove the hair, and an approximately 2-cm2 sample of skin including epidermis, dermis, and associated subcutaneous connective tissue or approximately 0.5 cm3 liver was flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen until use, and the RNA was prepared as described previously.14 The total yield of RNA from the skin was approximately 5 μg. Total skin RNA (5 μg) or liver RNA (15 μg) was resolved on denaturing 1% agarose, 5.5% formaldehyde gels, transferred to GeneScreen Plus (NEN Research Products Inc, Boston, MA), and hybridized to [α 32P]-dCTB–labeled (Prime-It Kit; Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) Timp-1–specific probes. Membrane prehybridizations, hybridizations, and washes were performed as previously described.20

Gelatin zymography.ESbL-lacZ cells in exponential growth were washed with PBS and maintained in serum-free medium for 24 hours. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation, and the supernatant was collected as conditioned medium. Protein concentration was determined using Bradford reagents (Bio-Rad, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). Three to 5 μg protein was separated by SDS-PAGE in an 8% polyacrylamide gel containing 0.1% gelatin. Following electrophoresis, gels were soaked in 2.5% Triton X-100 for 30 minutes and then incubated for 48 hours in substrate buffer (50 mmol/L Tris, pH 7.5, 5 mmol/L CaCl2 , and 40 mmol/L NaN3 ). Gels were then stained with Coomassie blue and destained to visualize bands of gelatinolytic activity.

X-Gal staining of whole organs.Livers were removed from the animals and washed in ice-cold PBS, fixed for 90 minutes in 2% paraformaldehyde, 0.1 mol/L PIPES, pH 6.9, 2 mmol/L MgCl2 , and 1.25 mmol/L EGTA, pH 8.0, at 4°C, washed three times in ice-cold PBS, and then incubated in X-Gal solution containing 5 mmol/L K3 [Fe(CN)]6 , 5 mmol/L K4Fe(CN)6⋅3H20, 2 mmol/L MgCl2 , 0.01% sodium desoxycholate, 0.02% NP40, 1 mg/mL X-Gal (Boehringer, Laval, Quebec, Canada) at 37°C for 12 to 14 hours as previously described.19 Under these conditions, endogenous β-galactosidase activity is not detectable.

Reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction.cDNA was synthesized on 5 μg total RNA with Superscript II reverse transcriptase (RT) (GIBCO-BRL, Burlington, Canada) at 45°C using oligo d(T)12-18 primers, and was subsequently incubated with RNAase H. A 2-μL aliquot of the cDNA reactions was used for 35 cycles (1 minute at 94°C, 1 minute at 64°C, and 72°C for 1 minute plus a 1-second extension per cycle) of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using Timp-1–specific primers (5′-ACTCTTCACTGCGGTTCTGGGAC and 3′-GTCATAAGGGCTAAATTCATGGG) and Taq DNA polymerase (GIBCO-BRL). The expected product of a 196-bp fragment of Timp-1 cDNA was visualized on ethidium bromide–stained 1.8% agarose gel.

Statistical analysis.Data were analyzed using Student's t-test. Values were considered significant at P less than .05.

RESULTS

Characterization of the Model: Timp-1 Expression in Transgenic Mice and in the ESbL-lacZ Lymphoma Cell Line

The host.To study the impact of Timp-1 on spontaneous metastasis, modulation of Timp-1 by Timp-1 transgene expression was delineated both at the site of primary tumor growth (the skin) and in the target organ of spontaneous lymphoma metastasis (the liver). Figure 1A shows the presence of Timp-1 sense and Timp-1 antisense transgene mRNAs in the skin of transgene-positive mice and their absence in transgene-negative control littermates. Endogenous Timp-1 mRNA was undetectable in the skin. We have previously described the transgenic lines used here with respect to net changes of Timp-1 mRNA and protein in the liver.14 Expression of Timp-1 transgene mRNA in Timp-1–overexpressing (Ts-4, designated here as Timp-1high) and in Timp-1 antisense RNA–expressing (Ta-1, designated here as Timp-1low) livers was confirmed in the respective DBA/2 backcrosses (Fig 1B). Although Timp-1 mRNA was not seen by Northern analysis, basal levels of Timp-1 in the skin and liver of control animals were detectable with the more sensitive method of RT-PCR (Fig 1C).

Timp-1 expression in skin and liver. (A) Total RNA was isolated from hairless skins of Ts-4 (Timp-1high) or Tsa-1 (Timp-1low) mice, which had been backcrossed with DBA/2 mice, and 5 μg RNA was analyzed on a Northern blot. RNA from a cell line (H59.NA3 Lewis lung carcinoma) served as a control for migration of endogenous Timp-1 (0.9 kb) mRNA in the Northern blots in A and B. Transgenic sense and antisense Timp-1 RNAs are larger (1.1 kb) due to the 5′ noncoding sequence from the -t r a n s c r i p t i o n a l p r o m o t e r . ( ;k1 ) T r a n s g e n e - p o s i t i v e m i c e ; ( ;k2 ) -transgene-negative (wild-type) littermates. The lower panel shows equal hybridization with 18S rRNA among the samples, indicating equal RNA loading. (B) Hepatic expression of sense (in Ts-4/DBA Timp-1high mice) and antisense -( i n T a - 1 / D B A T i m p - 1l o w m i c e ) -Timp-1 RNA. Fifteen micrograms of total liver RNA was analyzed by Northern hybridization using double-stranded [α32P]-dCTP–labeled probes specific for Timp-1 or 18S rRNA. (C) Agarose gel (1.8%) showing the 196-bp fragment of the amplified sequence of Timp-1. The positive control is the Timp-1–positive cell line H59.NA3.

Timp-1 expression in skin and liver. (A) Total RNA was isolated from hairless skins of Ts-4 (Timp-1high) or Tsa-1 (Timp-1low) mice, which had been backcrossed with DBA/2 mice, and 5 μg RNA was analyzed on a Northern blot. RNA from a cell line (H59.NA3 Lewis lung carcinoma) served as a control for migration of endogenous Timp-1 (0.9 kb) mRNA in the Northern blots in A and B. Transgenic sense and antisense Timp-1 RNAs are larger (1.1 kb) due to the 5′ noncoding sequence from the -t r a n s c r i p t i o n a l p r o m o t e r . ( ;k1 ) T r a n s g e n e - p o s i t i v e m i c e ; ( ;k2 ) -transgene-negative (wild-type) littermates. The lower panel shows equal hybridization with 18S rRNA among the samples, indicating equal RNA loading. (B) Hepatic expression of sense (in Ts-4/DBA Timp-1high mice) and antisense -( i n T a - 1 / D B A T i m p - 1l o w m i c e ) -Timp-1 RNA. Fifteen micrograms of total liver RNA was analyzed by Northern hybridization using double-stranded [α32P]-dCTP–labeled probes specific for Timp-1 or 18S rRNA. (C) Agarose gel (1.8%) showing the 196-bp fragment of the amplified sequence of Timp-1. The positive control is the Timp-1–positive cell line H59.NA3.

The tumor cell challenge.Endogenous Timp-1 mRNA was undetectable in ESbL-lacZ lymphoma cells grown in culture (Fig 2A). The ability of ESbL-lacZ lymphoma cells to produce and secrete metalloproteinases was tested using the conditioned media in a zymogram assay, which showed that these cells are capable of producing the latent forms of both the 92-kD gelatinase B (MMP-9) and 72-kD gelatinase A (MMP-2; Fig 2B).

Lack of Timp-1 mRNA expression and presence of gelatinase activity in conditioned media of ESbL-lacZ cells. (A) Total RNA isolated from ESbL-lacZ or H59.NA3 (Lewis lung carcinoma used as positive control) cells was analyzed by Northern blotting. Lower panel shows the loading control, 18S rRNA. (B) Zymographic analysis was performed using 5 μg protein from mammary tissue or freshly collected ESbL-lacZ–conditioned media. Mouse mammary tissue served as a positive control for enzymatic activity. 92-kD gelatinase A (MMP-9) and 72-kD gelatinase B (MMP-2) are indicated.

Lack of Timp-1 mRNA expression and presence of gelatinase activity in conditioned media of ESbL-lacZ cells. (A) Total RNA isolated from ESbL-lacZ or H59.NA3 (Lewis lung carcinoma used as positive control) cells was analyzed by Northern blotting. Lower panel shows the loading control, 18S rRNA. (B) Zymographic analysis was performed using 5 μg protein from mammary tissue or freshly collected ESbL-lacZ–conditioned media. Mouse mammary tissue served as a positive control for enzymatic activity. 92-kD gelatinase A (MMP-9) and 72-kD gelatinase B (MMP-2) are indicated.

Effect of Host Timp-1 Modulation on Tumor Take and Kinetics of ESbL-lacZ Primary Tumor Growth

Primary tumors were detected in 100% of the control wild-type littermates within 10 days of intradermal injection of 5 × 103 ESbL-lacZ cells. Tumor incidence remained at 100% in Timp-1low mice, but the Timp-1high group showed a reduction in tumor take of 20% or 40% in two of the three independent experiments (Table 1). To confirm that the reduced tumor take in Timp-1high mice was not a consequence of faulty injections, we rechallenged these mice with a 10-fold higher dose of tumor cells 5 weeks later and again found a failure of tumor take (Table 1).

Parameters of Tumor Growth Affected by Timp-1 Expression

| . | Experiment 1 . | Experiment 2 . | Experiment 3 . | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Timp-1high . | Control . | Timp-1low . | Control . | Timp-1high . | Control . | Timp-1low . | Control . | Timp-1high . | Control . | Timp-1low . | Control . |

| Primary tumor | ||||||||||||

| Tumor take | 3/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 4/5 | 2/2 | 4/4 | 3/3 | 3/3 | 2/2 | 2/2 | 3/3 |

| Tumors after rechallenge | 0/2 | — | — | — | 0/1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| DAI to tumor diameter 8.5 mm | 34 | 21 | 16 | 21 | 31 | 20 | 15 | 21 | 33 | 21 | 16 | 22 |

| t50 survival | 45 | 32 | 26 | 32 | 42 | 30 | 26 | 31 | 45 | 31 | 27 | 32 |

| Spontaneous metastasis | ||||||||||||

| Periportal localization | 3/3 | 5/5 | 2/5 | 5/5 | 4/4 | 2/2 | 1/4 | 3/3 | ND | |||

| Diffuse infiltration | 0/3 | 0/5 | 3/5 | 0/5 | 0/4 | 0/2 | 3/4 | 0/3 | ND | |||

| . | Experiment 1 . | Experiment 2 . | Experiment 3 . | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Timp-1high . | Control . | Timp-1low . | Control . | Timp-1high . | Control . | Timp-1low . | Control . | Timp-1high . | Control . | Timp-1low . | Control . |

| Primary tumor | ||||||||||||

| Tumor take | 3/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 5/5 | 4/5 | 2/2 | 4/4 | 3/3 | 3/3 | 2/2 | 2/2 | 3/3 |

| Tumors after rechallenge | 0/2 | — | — | — | 0/1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| DAI to tumor diameter 8.5 mm | 34 | 21 | 16 | 21 | 31 | 20 | 15 | 21 | 33 | 21 | 16 | 22 |

| t50 survival | 45 | 32 | 26 | 32 | 42 | 30 | 26 | 31 | 45 | 31 | 27 | 32 |

| Spontaneous metastasis | ||||||||||||

| Periportal localization | 3/3 | 5/5 | 2/5 | 5/5 | 4/4 | 2/2 | 1/4 | 3/3 | ND | |||

| Diffuse infiltration | 0/3 | 0/5 | 3/5 | 0/5 | 0/4 | 0/2 | 3/4 | 0/3 | ND | |||

In 3 independent experiments, parameters of the primary tumor and spontaneous metastasis were measured in Timp-1high mice, Timp-1low mice, and their respective control littermates.

Abbreviations: DAI, days after tumor cell inoculation; t50, DAI when 50% of the animals are dead; ND, not determined.

The growth of intradermal primary tumors followed similar linear kinetics in the control wild-type littermates of both Timp-1low and Timp-1high breeds. Tumors in wild-type mice reached a median diameter of 8.5 mm (the half-maximal tumor diameter) at 20 to 22 days (Table 1). In Timp-1low mice, the primary tumor growth was accelerated compared with the wild-type controls, and this divergence became more apparent in the later period between days 15 and 30 after tumor cell inoculation. Consequently, the half-maximal tumor diameter was achieved 5 days earlier, at day 16 (Table 1), and the end-point value approximately 10 days earlier than in the control group (Table 1). In Timp-1high mice, the primary tumor growth was retarded and a plateau phase was observed between days 20 and 30 after tumor cell inoculation (data not shown). The half-maximal tumor diameter of 8.5 mm was seen at day 34, 13 days later than in the controls (Table 1).

Even though the growth-inhibitory effect in Timp-1high mice and growth-promoting effect in Timp-1low mice could be abrogated upon increasing the dose of inoculated tumor cells 10-fold, the overall tendency of larger tumors in Timp-1low mice and of smaller tumors in Timp-1high mice compared with their respective controls persisted over the entire course of tumor growth (data not shown).

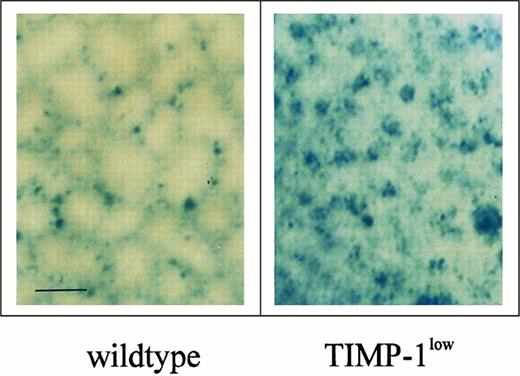

Effect of Host Timp-1 Modulation on Survival and Spontaneous Metastasis

Survival was shortened by 6 days in Timp-1low mice (t50 = 26 v 32 days), whereas it was substantially prolonged by 13 days in Timp-1high mice (t50 = 45 v 32 days; Table 1). We also monitored spontaneous liver metastases of ESbL-lacZ cells in moribund mice. The intraorgan metastatic pattern of ESbL-lacZ variants has been well characterized macroscopically and histologically and reported previously18: tumor cells are most prominent in the periportal areas, with distribution along the perilobular structure of the functional subunits of the liver. Only a few single cells infiltrate the liver parenchyma within the lobuli. In the present study, such a mosaic pattern of metastasis was consistently observed in the wild-type control groups (Fig 3). Spontaneous metastasis in livers of Timp-1high mice showed a mosaic pattern identical to that shown in Fig 3 (wild-type), whereas a dissolution of this mosaic pattern was seen in Timp-1low livers (Fig 3). In the majority (60% to 75%; Table 1) of Timp-1low mice, the liver parenchyma was extensively infiltrated with tumor cells, as shown by an increased presence of blue X-Gal staining, with less restricted localization to the perilobular areas.

Pattern of spontaneous liver metastases in moribund Timp-1low and wild-type mice. Whole-organ X-Gal staining showed a mosaic perilobular pattern in control wild-type mice. In livers of Timp-1low mice, a focal/clustered metastasis pattern was detected, showing effective infiltration of the parenchyma of the liver lobuli (bar, 0.5 mm).

Pattern of spontaneous liver metastases in moribund Timp-1low and wild-type mice. Whole-organ X-Gal staining showed a mosaic perilobular pattern in control wild-type mice. In livers of Timp-1low mice, a focal/clustered metastasis pattern was detected, showing effective infiltration of the parenchyma of the liver lobuli (bar, 0.5 mm).

Experimental Metastasis of ESbL-lacZ Lymphoma Cells in Timp-1–Modulated Livers

It is known for many tumors that the kinetics of spontaneous metastasis is linked to the kinetics of primary tumor growth. It is important to note that both the site of primary tumor growth and the target organ for metastasis are modulated with respect to Timp-1 expression in our model. Therefore, we used experimental metastasis assays to separate the effects of Timp-1 on target organ colonization from parameters dependent on primary tumor growth.

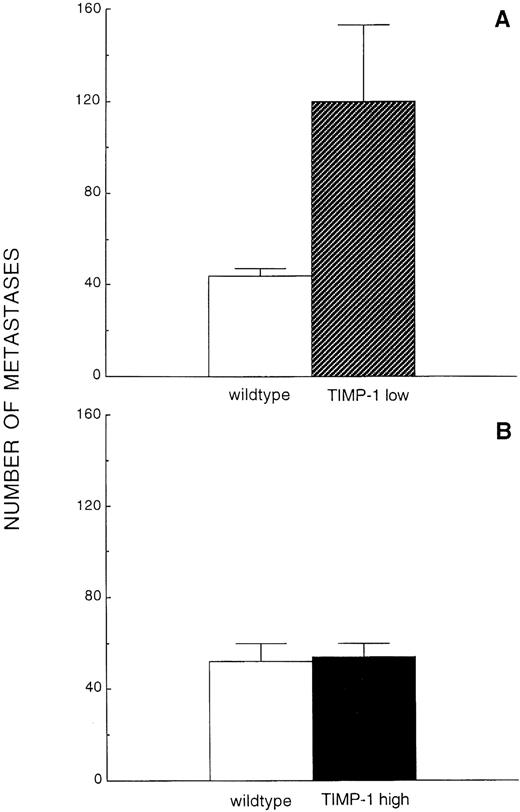

The optimal window for metastasis quantification was first established by injecting ESbL-lacZ cells intravenously with subsequent whole-mount X-Gal staining of the livers, with examination at macroscopic and microscopic levels on days 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 after inoculation. Day 8 was selected for further experiments, since macroscopically visible, distinct, and countable metastatic foci on the liver surface, ranging between 30 and 60 in number, were discernible at this time point (Fig 4A). Quantification of macroscopic foci in livers of Timp-1low mice showed a substantial and significant increase of greater than 100% (44 ± 3 in control v 120 ± 33 in Timp-1low, P = .001, n = 6/6; Fig 5A). In sharp contrast to the control wild-type littermates, where the pattern of experimental liver metastasis was focal with random distribution over all liver lobes (Fig 4B), livers of Timp-1low mice had numerous (> 500) additional micrometastases consisting of only a few cells present throughout the liver surface (Fig 4B). When Timp-1high mice were challenged with ESbL-lacZ lymphoma cells, the number of macroscopic foci was unaltered (52 ± 8 in control v 54 ± 6 in Timp-1high, n = 6/6; Fig 5B). In addition, the metastatic pattern remained unaffected and was identical to that shown in Fig 4B (wild-type).

Experimental liver metastases in Timp-1low mice. (A) 1 × 105 ESbL-lacZ cells were injected intravenously (tail vein), and the livers were removed 8 days later. Whole-organ X-Gal–stained livers of wild-type control and Timp-1low mice are shown (bar, 5 mm). (B) Micrometastatic cell clusters in livers of Timp-1low mice. Numerous additional cell clusters (< 500) composed of a few cells were dispersed 8 days after inoculation among the macroscopically visible metastatic foci (arrows) in Timp-1low mice, but were absent in wild-type animals (bar, 0.5 mm).

Experimental liver metastases in Timp-1low mice. (A) 1 × 105 ESbL-lacZ cells were injected intravenously (tail vein), and the livers were removed 8 days later. Whole-organ X-Gal–stained livers of wild-type control and Timp-1low mice are shown (bar, 5 mm). (B) Micrometastatic cell clusters in livers of Timp-1low mice. Numerous additional cell clusters (< 500) composed of a few cells were dispersed 8 days after inoculation among the macroscopically visible metastatic foci (arrows) in Timp-1low mice, but were absent in wild-type animals (bar, 0.5 mm).

Quantification of experimental liver metastasis in Timp-1low and Timp-1high mice. Macroscopic foci were counted 8 days after intravenous injection of 1 × 105 ESbL-lacZ cells in Timp-1low (A) and Timp-1high (B) mice following whole-organ X-Gal staining. The numerous micrometastases in Timp-1low mice are not included in this quantification.

Quantification of experimental liver metastasis in Timp-1low and Timp-1high mice. Macroscopic foci were counted 8 days after intravenous injection of 1 × 105 ESbL-lacZ cells in Timp-1low (A) and Timp-1high (B) mice following whole-organ X-Gal staining. The numerous micrometastases in Timp-1low mice are not included in this quantification.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have demonstrated that modulation of Timp-1 expression within a host can directly influence the growth and progression of a malignant lymphoma that expresses MMPs. Specifically, the reduction of Timp-1 in Timp-1low transgenic mice led to faster primary tumor growth, more aggressive spontaneous metastasis, and earlier death. In addition, the livers from Timp-1low mice allowed a more aggressive colonization with an experimental metastasis challenge. The reciprocal was observed in Timp-1high mice, which exhibited resistance to tumor formation, leading to longer survival. However, metastatic colonization of the liver by the T-cell lymphoma was not hindered by elevated Timp-1 levels.

A tumoristatic effect of Timp-1 was evident in our model, such that a modest increase of Timp-1 due to the expression of the transgene inhibited development of intradermal primary tumors. Whereas overexpression of Timp-1 reduced the tumor take and dramatically retarded primary tumor growth, tumor growth was marginally enhanced in the Timp-1low environment. One of the determining parameters for successful and continuous tumor growth is angiogenesis,21 which also requires MMP-mediated ECM degradation.22 Both TIMP-1 and TIMP-2 have previously been shown to inhibit angiogenesis in chicken chorioallantoic membranes.23 Recently, using our transgenic mouse lines, we have reported that elevated hepatic Timp-1 levels inhibit SV40 T antigen–induced hepatocellular carcinoma. This Timp-1–mediated inhibition was associated with decreased angiogenesis in these large primary parenchymal tumors that originate within this tissue and are dependent on angiogenesis for growth.4,24 In the present study, Timp-1 within the skin may continuously exert an inhibitory effect on MMPs secreted by the lymphoma and on neovascularization of the expanding tumor by inhibiting, in part, the endothelial cell migration, as suggested from an in vitro angiogenesis model.25

Upon tumor challenge with a T-cell lymphoma, modulation of Timp-1 in the skin had far-reaching biologic consequences for the host, ultimately shortening the survival of Timp-1low animals while extending it in Timp-1high animals. In spontaneous metastasis, the outcome at the afflicted site of metastasis is a combination of multiple steps, some of which depend on the primary tumor itself. For example, slower primary tumor growth (which we observe with TIMP-1 overexpression) would lead to delayed spontaneous metastasis, and eventually to longer life. To examine the influence of Timp-1 levels on the later steps of metastasis, ie, invasion into the target tissue, survival, and growth of metastases within the Timp-1–modulated liver microenvironment, we used the experimental metastasis approach. In Timp-1low mice, we found at least a doubling of metastatic foci, as well as numerous additional micrometastases, which reflected a more successful colonization. Increased ECM turnover, which would be induced by a net increase in proteolytic activity due to the lack of Timp-1, not only would facilitate invasion of tumor cells into the target organ but may also lead to increased bioavailability of growth factors sequestered within the ECM.26 These events will directly affect the growth of micrometastases that would otherwise remain dormant. This may be the reason for the formation of additional micrometastases (Fig 4B), leading to a substantial increase in the metastasis load as seen in Timp-1low mice.

Antisense RNA is believed to bind the endogenous transcript with an ultimate downregulation of the particular protein level. Skin and hepatic Timp-1 mRNA, although undetectable by Northern blotting, could indeed be detected using the more sensitive method of RT-PCR. Furthermore, induction of endogenous Timp-1 mRNA occurred in liver tissue following the metastasis challenge (data not shown), which would provide additional substrate for the antisense RNA. Our studies are unique in that antisense technology–based genetic modulation in transgenic mice is providing effective models to study tumorigenesis and metastasis.

High TIMP-1 expression in stromal cells has been found in more aggressive lymphomas.6,16 17 This led us to the question whether TIMP-1 is a host defense response or a factor promoting the aggressiveness of lymphomas. In the present study, overexpression of Timp-1 in the host target organ did not suppress experimental metastasis, thereby failing to exert a defense against lymphoma, although Timp-1–compromised livers in Timp-1low mice facilitated lymphoma infiltration and growth of micrometatases. This indicates that a threshold level of endogenous Timp-1 may be necessary to limit metastasis, but elevated levels are not sufficient to confer protection.

In this study, we observed that the intradermal primary tumor of the lymphoma was inhibited by Timp-1 overexpression, and we previously reported that Timp-1 inhibited T-antigen–induced hepatocellular carcinoma, at least in part by inhibiting angiogenesis.14 However, in the present study, we did not see Timp-1 inhibition of experimental lymphoma metastasis. Therefore, a differential effect of Timp-1 overexpression on the intradermal primary tumor vs liver metastasis was observed. We propose that the Timp-1–mediated effect on angiogenesis may play a role in the intradermal primary tumor growth of the lymphoma similar to that observed in hepatocellular carcinoma,14,24 but angiogenesis may be less critical to lymphoma metastasis: the few (2 to 10) focal hepatocellular carcinomas caused by SV40 T antigen originate in the liver tissue and become large (> 5 mm), as does the single primary intradermal tumor, and eventually cause death by growing beyond 2 cm in size.14 In contrast, many secondary lymphoma metastases are scattered throughout the liver and remain much smaller (0.1 to 0.7 mm), with morbidity resulting from extensive infiltration of the liver tissue before these metastases grow large. Further, lymphomas are highly migratory, invasive, and inherently different from hepatocellular carcinoma, which remains focal and noninvasive. Therefore, angiogenesis is required for the very large primary tumors, but is less critical for the small lymphoma metastases. Another possibility is that ESbL-lacZ lymphoma may use the urokinase plasminogen activator system for invasion.27

Transgenic mouse models are now being introduced to study metastasis. Altered expression of host plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), which directly correlates with a poor prognosis in different cancers,28,29 did not influence experimental lung metastasis of B16 melanoma cells,30 although PAI-1–overexpressing mice had significantly fewer lung metastases in a Lewis lung carcinoma model.31 Recently, we found that inhibition of experimental metastasis of a fibrosarcoma to the brain was conferred by transgenic Timp-1 overexpression in the host.32 Here, we show that lymphoma metastasis to the liver is unaffected by Timp-1 overexpression, but is potentiated by Timp-1 reduction. Overall, failure or success of metastasis inhibition by overexpression of host protease inhibitors will likely depend on the tumor type and the target organ of metastasis.

It is well-established that upon transfection, TIMPs are able to directly affect the invasion and metastasis of cell lines.7 33-35 However, it is now appreciated that not only tumor cells but also the host stroma are integral to cancer progression. Our study addressed the causal relationship between host Timp-1 expression and malignancy. The response of Timp-1 transgenic hosts to the tumor challenge revealed the importance of Timp-1 in the progression of a T-cell lymphoma. Timp-1 overexpression inhibited primary tumor growth, and a lack of hepatic Timp-1 augmented lymphoma malignancy. The fact that lymphoma metastases bypassed the protection expected from Timp-1 overexpression suggests caution in generalizing the metastasis-inhibitory effect of metalloproteinase inhibitors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We gratefully acknowledge Dr V. Schirrmacher of the German Cancer Research Center, Heidelberg, Germany, for the generous gift of L-CI.5s cells, and Dr O.H. Sanchez-Sweatman, Dr P. Waterhouse, and A.T. Ho for helpful discussions.

Supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute of Canada, and in part by a Feodor Lynen Stipend from the Alexander von Humboldt Stiftung (A.K.) and a Medical Research Council of Canada Scholarship (R.K.).

Address reprint requests to Rama Khokha, PhD, Ontario Cancer Institute, 610 University Ave, Toronto, Ontario M5G 2M9, Canada.

![Fig. 1. Timp-1 expression in skin and liver. (A) Total RNA was isolated from hairless skins of Ts-4 (Timp-1high) or Tsa-1 (Timp-1low) mice, which had been backcrossed with DBA/2 mice, and 5 μg RNA was analyzed on a Northern blot. RNA from a cell line (H59.NA3 Lewis lung carcinoma) served as a control for migration of endogenous Timp-1 (0.9 kb) mRNA in the Northern blots in A and B. Transgenic sense and antisense Timp-1 RNAs are larger (1.1 kb) due to the 5′ noncoding sequence from the -t r a n s c r i p t i o n a l p r o m o t e r . ( ;k1 ) T r a n s g e n e - p o s i t i v e m i c e ; ( ;k2 ) -transgene-negative (wild-type) littermates. The lower panel shows equal hybridization with 18S rRNA among the samples, indicating equal RNA loading. (B) Hepatic expression of sense (in Ts-4/DBA Timp-1high mice) and antisense -( i n T a - 1 / D B A T i m p - 1l o w m i c e ) -Timp-1 RNA. Fifteen micrograms of total liver RNA was analyzed by Northern hybridization using double-stranded [α32P]-dCTP–labeled probes specific for Timp-1 or 18S rRNA. (C) Agarose gel (1.8%) showing the 196-bp fragment of the amplified sequence of Timp-1. The positive control is the Timp-1–positive cell line H59.NA3.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/90/5/10.1182_blood.v90.5.1993/4/m_bl_0008f1.jpeg?Expires=1766039245&Signature=RYAy2lrCCrbnbJSlhl5W-VJAwPnyf4SIZ6Xci4OISz~AWGaCI7cOf5cTPHXRSZSk41-SZssj31fB1JzyVeJli0NzQXveSnKvfM31Uxjecjb85S6VL4ntFJVcyYG1PDQa7Ve4GI2oQ7qldLOiTJ-HA8Hm5pVNpeFrjNHVqVwN3CQvEt2sMuQW38eQmYtyMNKhGFuhWVVFeHaJ5uDU-B4Ew6-C~sxGCPaNEiRIg9KxlG6veIFrUNx4xtrM-4n6AJv2uZIVLPQUStlCBJgiD1f-QjyuQBlJRHUvGrOyoAXw7Rgbms2c56D5zoe2-HOe7opJS98IPFiROKRy7ytRejfaHA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal