Abstract

Age is an important prognostic parameter, especially in patients with advanced high-grade non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (HG-NHL) who require more intensive and extensive therapy for any possible chance of cure. We investigated the potential of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF ) for reducing myelotoxicity, which is the most important dose-limiting factor for chemotherapy. Between March 1993 and June 1995, 158 previously untreated patients 60 years and older with HG-NHL were included in a cooperative randomized comparative trial and treated with a combination therapy including VNCOP-B (cyclophosphamide, mitoxantrone, vincristine, etoposide, bleomycin, and prednisone) with or without G-CSF. G-CSF was administered at 5 μg/kg/d throughout the treatment starting on day 3 of every week for 5 consecutive days. Of the 158 patients registered for the trial, 149 patients were evaluable: 77 received VNCOP-B plus G-CSF and 72 received VNCOP-B alone. The overall response rate was 81.5%, with complete response in 59%: 60% in the VNCOP-B plus G-CSF group, and 58% in the VNCOP-B group. At 30 months (median 24 months), 68% of all complete responders were alive without disease in the G-CSF group and 65% in the control group. Neutropenia occurred in 18 out of 77 (23%) of the G-CSF treated patients and in 40 out of 72 (55.5%) of the controls (P = .00005). Clinically relevant infections occurred in 4 out of 77 (5%) of the G-CSF group and in 15 out of 72 (21%) of the controls (P = .004). The delivered dose intensity was higher in patients receiving G-CSF (95% v 85%), but the difference was not statistically significant. Our data show that VNCOP-B is a feasible and effective regimen in elderly HG-NHL patients, and that the use of G-CSF reduces infection and neutropenia rates without producing any significant modifications to the dose intensity, CR rate, and relapse-free survival curve.

UNTIL NOW, patients aged 60 to 65 years or older with aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL) have often been excluded from clinical trials. In the last several years, the average life expectancy of 60-year-olds has increased to 15 to 20 years. We are currently witnessing a substantial increase in the incidence of lymphomas, and of NHLs in particular.1-3 The aging of the population will increase the percentage of elderly persons affected by lymphoma in the coming years.

Elderly HG-NHL patients present a high mortality rate for different causes: (1) a generational risk, with more frequent deaths apparently unrelated to lymphoma or its treatment; (2) a greater risk of iatrogenic mortality due to increased organ toxicity from bleomycin, vinca alkaloids, and anthracyclines4-6; (3) the frequency of concomitant comorbid conditions increased with age (hypertension, depression, osteoporosis, respiratory disease, diabetes, etc)7; (4) a lower response rate, accompanied by a reduction in median survival, because of decreased drug dosage.

Several authors have concluded that age is an important prognostic factor in the treatment of these patients.8-12 Following this analysis, effective chemotherapy regimens have recently been specifically designed and tested on elderly patients with high-grade non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (HG-NHL).13-26 Several of these trials highlight the tendency to treat elderly patients with lower doses of chemotherapy to diminish treatment-related toxicity while at the same time emphasizing the fact that older HG-NHL patients benefit from full-dose therapy.

Third generation chemotherapy regimens capable of curing HG-NHL in about 50% of patients induce severe toxicity in older patients. Myelosuppression is the most important limiting factor in this age subset of patients, and hemopoietic growth factors can reduce hematologic toxicity.27 28

To minimize the toxicity associated with oupatient chemotherapy regimens, we designed an 8-week pilot regimen for treating HG-NHL using moderate doses of chemotherapy at frequent dosing intervals, and obtained a good remission rate.16 Subsequently, we commenced a multicenter randomized trial including granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF ) as a further component of treatment to determine whether toxicity can be further reduced without sacrificing efficacy. In this report we summarize the data of this trial on 158 previously untreated HG-NHL patients.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Between March 1993 and June 1995, from 12 Italian cooperative institutions, 158 previously untreated patients 60 years and older with HG-NHL entered the study. Diagnostic specimens of all patients were reviewed and classified according to the updated Kiel classification.29 Eligibility criteria were: confirmed diagnosis of HG-NHL: diffuse large-cell centroblastic and immunoblastic lymphoma (group G-H according to the Working Formulation [WF ]),30 anaplastic large cell and peripheral T-cell lymphoma (unclassifiable according to the WF); stage II to IV as outlined by the Ann Arbor Conference31; performance status 0 to 2 according to the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group32; human immunodeficiency virus negative; normal hepatic, cardiac, and renal functions.

Staging evaluation included initial hematologic and chemical survey, in addition to chest x-rays, abdominal ultrasonography, computerized tomography of the chest and abdomen, and bone marrow biopsy in all patients. No patient underwent staging laparotomy. Bulky disease was defined as a tumor mass ≥6 cm.

Of the 158 patients enrolled, 149 patients (77 in the VNCOP-B plus G-CSF arm and 72 in the VNCOP-B alone arm) fulfilled the criteria for entry. Nine patients were excluded because of: incorrect diagnosis (2 patients); lost to follow-up (4 patients), and protocol violations (3 patients: 2 with discordant lymphoma, and 1 Hepatitis B Virus [HBV] and Hepatitis C Virus [HCV] positive). All patients gave written informed consent. Randomization was done according to a 1:1 ratio.

The characteristics of the 149 patients are shown (Table 1).

Clinical Characteristics of 149 Elderly Patients With HG-NHL

| . | G-CSF (77 patients) . | Control (72 patients) . |

|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | ||

| Median | 69 | 70 |

| Range | 60-82 | 60-80 |

| Sex (male/female) | 35/42 | 34/38 |

| Symptoms (no/yes) | 50/27 | 48/24 |

| Stage (%) | ||

| II | 25 (32) | 25 (35) |

| III | 22 (28) | 18 (25) |

| IV | 30 (40) | 29 (40) |

| Bulky disease (%) | 24 (31) | 18 (25) |

| LDH (>normal) (%) | 30 (38) | 25 (35) |

| Performance status (%) | ||

| 0-1 | 66 (82) | 60 (83) |

| 2 | 11 (18) | 12 (17) |

| Extranodal sites (no/yes) | 49/28 | 45/27 |

| Histology (%) | ||

| Centroblastic | 40 (52) | 35 (49) |

| Immunoblastic | 22 (28.5) | 23 (32) |

| Anaplastic large cell | 5 (6.5) | 4 (5.5) |

| Peripheral T cell | 10 (13) | 10 (13.5) |

| . | G-CSF (77 patients) . | Control (72 patients) . |

|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | ||

| Median | 69 | 70 |

| Range | 60-82 | 60-80 |

| Sex (male/female) | 35/42 | 34/38 |

| Symptoms (no/yes) | 50/27 | 48/24 |

| Stage (%) | ||

| II | 25 (32) | 25 (35) |

| III | 22 (28) | 18 (25) |

| IV | 30 (40) | 29 (40) |

| Bulky disease (%) | 24 (31) | 18 (25) |

| LDH (>normal) (%) | 30 (38) | 25 (35) |

| Performance status (%) | ||

| 0-1 | 66 (82) | 60 (83) |

| 2 | 11 (18) | 12 (17) |

| Extranodal sites (no/yes) | 49/28 | 45/27 |

| Histology (%) | ||

| Centroblastic | 40 (52) | 35 (49) |

| Immunoblastic | 22 (28.5) | 23 (32) |

| Anaplastic large cell | 5 (6.5) | 4 (5.5) |

| Peripheral T cell | 10 (13) | 10 (13.5) |

Drug Doses and Treatment Schedule for VNCOP-B

| Drug . | Dose . | Route . | Timing . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclophosphamide | 300 mg/m2 | IV | wk 1, 3, 5, 7 |

| Mitoxantrone | 10 mg/m2 | IV | wk 1, 3, 5, 7 |

| Vincristine | 2 mg | IV | wk 2, 4, 6, 8 |

| Etoposide | 150 mg/m2 | IV | wk 2, 6 |

| Bleomycin | 10 mg/m2 | IV | wk 4, 8 |

| Prednisone | 40 mg | IM | daily, dose tapered over the last 2 wk |

| Drug . | Dose . | Route . | Timing . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclophosphamide | 300 mg/m2 | IV | wk 1, 3, 5, 7 |

| Mitoxantrone | 10 mg/m2 | IV | wk 1, 3, 5, 7 |

| Vincristine | 2 mg | IV | wk 2, 4, 6, 8 |

| Etoposide | 150 mg/m2 | IV | wk 2, 6 |

| Bleomycin | 10 mg/m2 | IV | wk 4, 8 |

| Prednisone | 40 mg | IM | daily, dose tapered over the last 2 wk |

Abbreviation: IM, intramuscular.

VNCOP-B regimen and G-CSF schedule.The VNCOP-B program is similar to a MACOP-B (methotrexate, adriamycin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone, bleomycin)–like regimen33 with several distinctive features: in particular, treatment is completed in 8 weeks and includes mitoxantrone and etoposide instead of doxorubicin and methotrexate, respectively. We selected these replacements for the purpose of reducing the incidence of cardiac side effects and mucositis. Drug doses, including prednisone, were slowly reduced; all treatment was given on an outpatient basis. Doses and schedule of the VNCOP-B program are shown in Table 2. All patients received bacterial and Pneumocystis carinii prophylaxis with cotrimoxazole during the entire course of therapy.

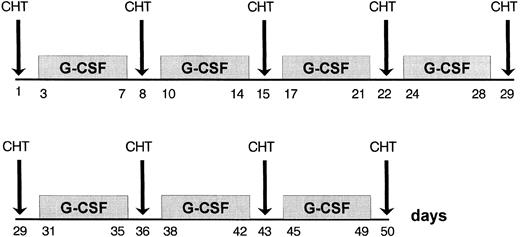

The G-CSF administration was 5 μg/kg/d subcutaneously throughout the treament, starting on day 3 of every week for 5 consecutive days (Fig 1).

Response.All patients were restaged after completion of chemotherapy. Clinical and pathological evaluations were made by repeating radiographic investigations and bone marrow biopsies if previous results had been positive.

Responses were graded according to standard criteria: complete response (CR) was defined as the complete disappearance of signs and symptoms due to disease, as well as normalization of all previous abnormal test results; partial remission (PR) was indicated by a reduction at least 50% of known disease with disappearance of systemic manifestations. No change or a response less than PR after 5 cycles was considered stable disease. Disease progression was indicated by the appearance of new lesions or by a 25% increase in the size of preexisting lesions.

Dose intensity was evaluated according to Hryniuk and Bush's model34; relative dose intensity was the ratio between dose intensity received and protocol dose intensity.

Statistical methods.Comparison between the 2 groups was based on the chi-square test for categorical data.35,36 Survival and relapse-free survival curves were calculated according to the method of Kaplan and Meier.37

Information on eight prognostic factors: sex, age, presence or absence of B symptoms, stage (II v III-IV), serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level, presence or absence of bulky disease, extranodal sites, histologic subtype, was associated with the outcome of all the patients. Adjustment for these prognostic factors when analyzing CRs was performed according to Cox's linear logistic model.36 To assess the effect of covariates on the relapse-free survival time, Cox's proportional hazards model was fitted.38 These two tests were performed with the SOLO statistical system (version 4.0) distributed by BMDP Statistical Software, Inc (Los Angeles, CA).

RESULTS

As can be seen from Table 1, the two groups of patients, randomized for the G-CSF arm (77 patients) versus the control arm (72 patients), are fully comparable in their main clinical and pathological features, without any statistically significant difference. The data monitoring committee observed no differences between the two arms such as to suggest interrupting the trial for ethical reasons.

Response to treatment.Clinical results are summarized in Table 3. In the VNCOP-B plus G-CSF group, the rate of CR was 60% (46 out of 77) as against 58% (42 out of 72) in the control group. There were 13 (17%) nonresponders (5 with stable disease, 8 with progressive disease) to VNCOP-B plus G-CSF, while in the control group there were 14 (20%) nonresponders (5 with stable disease, 9 with progressive disease).

Clinical Results

| . | G-CSF (77 patients) . | Control (72 patients) . |

|---|---|---|

| CR | 46/77 (60%) | 42/72 (58%) |

| PR | 18/77 (23%) | 16/72 (22%) |

| Stable disease | 5/77 (6.5%) | 5/72 (7%) |

| Progressive disease | 8/77 (10.5%) | 9/72 (13%) |

| . | G-CSF (77 patients) . | Control (72 patients) . |

|---|---|---|

| CR | 46/77 (60%) | 42/72 (58%) |

| PR | 18/77 (23%) | 16/72 (22%) |

| Stable disease | 5/77 (6.5%) | 5/72 (7%) |

| Progressive disease | 8/77 (10.5%) | 9/72 (13%) |

The CR rates for patients aged between 60 and 70 years and those older than 70 years were similar (61.5% v 56%).

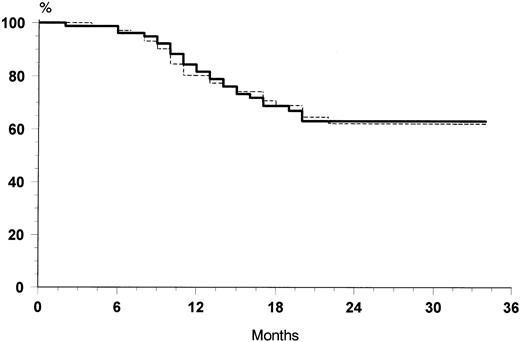

As regards the relapse-free interval, 8 out of 46 (17%) of the complete responders from the VNCOP-B plus G-CSF group had a relapse within 24 months, as compared with 8 out of 42 (19%) patients from the control group.

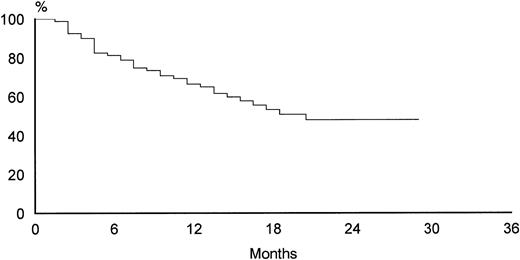

The overall rate of relapse-free survival for the 88 patients with CR was 74% at 30 months (median 24 months, range 6 to 32 months). No significant differences were observed at 30 months between the two treatment arms: 76% for VNCOP-B plus G-CSF and 72% for VNCOP-B alone, respectively (Fig 2). The overall survival at 30 months was 64% for VNCOP-B plus G-CSF and 62% for VNCOP-B alone, respectively (Fig 3). The global progression-free survival (indicating relapse, disease progression, or death from any cause) was 49% (Fig 4).

Relapse-free survival curves of G-CSF group (solid line) and control group (broken line).

Relapse-free survival curves of G-CSF group (solid line) and control group (broken line).

Overall survival curves of G-CSF group (solid line) and control group (broken line).

Overall survival curves of G-CSF group (solid line) and control group (broken line).

Toxic effects.Neutropenia less than 0.5 × 109/L occurred in 18 out of 77 (23%) patients treated with VNCOP-B plus G-CSF and in 40 out of 72 (55.5%) patients from the control group (P = .00005). The incidence of anemia and thrombocytopenia was similar in the two subsets of patients (less than 10%) and transfusions were not required (Table 4).

Analysis of Results and Toxic Effects

| . | G-CSF (77 patients) . | Control (72 patients) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| CR | 60% | 58% | NS |

| Neutropenia | 18/77 (23%) | 40/72 (55.5%) | .00005 |

| Infections | 4/77 (5%) | 15/72 (21%) | .004 |

| Dose intensity | 95% | 85% | NS |

| . | G-CSF (77 patients) . | Control (72 patients) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| CR | 60% | 58% | NS |

| Neutropenia | 18/77 (23%) | 40/72 (55.5%) | .00005 |

| Infections | 4/77 (5%) | 15/72 (21%) | .004 |

| Dose intensity | 95% | 85% | NS |

Abbreviation: NS, not significant.

Considering the treatment time scheduled at 8 weeks, the median time for completing the regimen was 8 weeks for the G-CSF group and 9.5 weeks for the control group.

The frequency of clinically relevant infections was recorded in 4 out of 77 (5%) of the G-CSF group as against 15 out of 72 (21%) of the controls (P = .004). The 4 G-CSF patients experienced only minor infections, requiring symptomatic treatment and/or oral antibiotics. By contrast, in the control group as well as 10 minor infections, there were 5 major infections requiring parenteral antibiotics and/or hospitalization, all of which involved the urinary tract (1 case) and the respiratory tract or sinuses (4 cases). In particular, these severe episodes were attributed to enterococcal infection (1 patient [pt]), staphylococcal infection (3 pts), and Pneumocystis c (1 pt).

Cardiac, liver, and renal problems were not observed, and there were no fatalities due to drug side effects during the treatment period; two patients died because of a pancreatic neoplasm (after 12 months from the end of the protocol) and of vascular accident (after 15 months from the treatment), respectively.

G-CSF was very well-tolerated in all patients except for two who reported episodes of musculoskeletal pain; this was controlled by simple analgesics and did not interrupt treatment. No patient refused G-CSF injections.

The dose intensity of cytotoxic chemotherapy was higher in patients receiving G-CSF, although the difference was not statistically significant: average relative dose intensity 95% versus 85% for G-CSF and control group, respectively. Most of the patients received more than 80% of the planned dose.

Statistical analysis.To evaluate whether any covariate prognostic factor could influence the outcome of the complete response, adjustment for the above mentioned prognostic factors was performed by the linear logistic model. The risk of a lower CR rate was correlated to the presence of bulky disease (P = .02) and advanced stage (III-IV) (P = .01). To evaluate the influence of prognostic factors on relapse-free survival, a Cox's proportional hazards regression was performed using the same covariates. Bulky disease and advanced stage were also poor prognostic factors for relapse-free survival (P = .02 and .004, respectively).

DISCUSSION

Approximately 30% to 40% of patients with aggressive lymphoma are over 60 years old. As regards first generation chemotherapeutic regimens, when in a SWOG study CHOP (cyclophosphamide, adriamycin, vincristine, and prednisone) chemotherapy was reduced by 50% in patients over 65 years of age, CR rates declined.39 However, in a small subset of patients over 65 years of age who received full doses, the CR rate approximated that of younger patients. Fisher et al40 confirmed that the gold-standard regimen for elderly HG-NHL patients was CHOP, but that the percentage of toxic deaths increased, and when the doses were reduced the CR rate decreased. Recently, two prospective, randomized studies41,42 have shown that the standard CHOP regimen can be given in sufficient doses to elderly aggressive lymphomas obtaining a CR rates between 49% and 68%.

Second and third generation programs appear to be too intensive to be administered to these patients without significantly escalating toxicity. Alternatively, new protocols specifically tailored to the tolerance and the biological rather than calendar age of patients have been reported to produce functional lymphoma therapy in the elderly.16-27 All these regimens were based on specific criteria: (1) to reduce toxic side effects; (2) to be of shorter duration; (3) to use methotrexate-free and doxorubicin-free regimens to reduce the incidence of mucositis and cardiomyopathy, respectively. The CR of these new protocols ranged between 45% and 75%.

We have previously reported that the VNCOP-B regimen can be considered effective and safe in a population of elderly patients with advanced HG-NHL.16 Following this we have set out to evaluate the role of G-CSF in this particular cancer population. In the last few years, randomized trials in young HG-NHL patients43 44 have shown that the use of growth factors (G-CSF or GM-CSF ) can significantly reduce the neutropenia episodes, number of infections, and intravenous (IV) antibiotic requirement.

In the present study on a large cohort of patients, the CR rate in elderly patients with HG-NHL was 59% with the VNCOP-B regimen, which is only slightly lower than that observed in younger (<60 years) HG-NHL patients. Furthermore, the relapse-free rate of 74% with a median of 24 months is similar to data from the younger HG-NHL population. This suggests that the role of older age as a significant risk factor for CR rate and relapse-free survival may be corrected and reduced by introducing particular devices in the therapeutical protocols. However, these data should be considered with caution, being the comparison based on retrospective trials only. The CR rate of 59% with VNCOP-B, now confirmed on a large cohort of patients, compares favorably with those reported by other third generation regimens.17,19,26,27 Comparison with CHOP or CHOP-like regimens40-42 is favorable, because we were able to obtain an equivalent rate of CR and 3-year survival without toxic deaths.

As regards the introduction of G-CSF, this is the first large randomized study of its effects during induction chemotherapy for HG-NHL in elderly patients. Our principal aim was to evaluate the role of G-CSF in decreasing granulocytopenia and infections, which are the most prominent toxic effects in almost all protocols. This trial has shown that G-CSF is well-tolerated in an outpatient setting, and is effective in reducing the morbidity associated with chemotherapy-induced neutropenia. In fact, patients who received G-CSF showed a significantly lower incidence of neutropenia (P = .00005) with the reduction of the number of infections (P = .004) and with the consequent decrease of IV antibiotic requirement and days of hospitalization. The addition of G-CSF probably does not increase the overall expenditure with respect to the antibiotics and hospitalization costs of the control group as reported by Zagonel et al.28 In addition, the study has shown the safety and the tolerability of G-CSF. On the other hand, the addition of G-CSF brought no improvement to the CR rate or relapse-free survival. The difference in dose intensity did not prove significant, probably because the VNCOP-B regimen is already a scheme designed to maximize dose intensity in the dosages, timing, and selection of drugs.

Therefore, we can conclude that the MACOP-B–like regimen, VNCOP-B is effective as regards the CR rate and relapse-free survival rate in elderly patients with advanced HG-NHL, and that in these older patients G-CSF plays a significant role in decreasing the neutropenia and infection rates. In view of the peculiar clinical features of these aged patients G-CSF could be included in standard regimens to optimize the feasibility and safety of specific “older patients” treatments. In addition, a prospective comparative study between standard CHOP and VNCOP-B (an 8-week chemotherapy regimen) is recommended with the aim to assess the optimal treatment protocol for this group of patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors acknowledge Dan L. Longo, MD (National Institute on Aging, Baltimore, MD) for careful review of the manuscript.

Address reprint requests to Pier Luigi Zinzani, MD, Istituto di Ematologia “L. e A. Seràgnoli,” Policlinico S. Orsola, Via Massarenti 9 40138 Bologna, Italy.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal