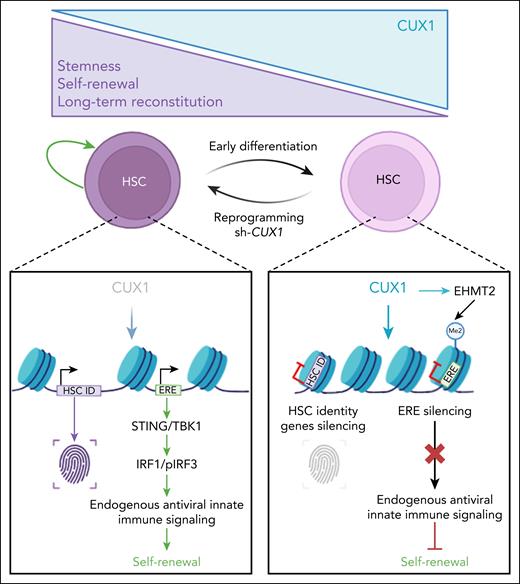

In this issue of Blood, Martinez et al1 reveal that the transcription factor CUX1 regulates hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) fate in a dose-dependent way. CUX1 normally suppresses retroelements (EREs), thus reduced CUX1 allows ERE-driven interferon signaling, thereby sustaining stemness through intrinsic immune activation.

CUX1 is a homeodomain transcription factor essential for development and a regulator of diverse processes in somatic stem cells across multiple tissues. It is frequently mutated or deleted in myeloid neoplasms with monosomy 7 or del(7q), and its loss independently predicts poor prognosis in both myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML). In mice, CUX1 deficiency disrupts hematopoiesis and induces MDS in a dose-dependent manner.

To assess the dose-dependent roles of CUX1 in hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), Martinez et al generated a reporter mouse with mCherry fused to endogenous CUX1 and combined it with a doxycycline-inducible Cux1 short hairpin RNA (shRNA) knockdown allele. This model, coupled with single-cell approaches, enabled dynamic tracking and modulation of CUX1 across hematopoietic differentiation. The authors observed a gradient of CUX1 protein within immunophenotypic HSCs that predicts stem cell activity: long-term repopulating HSCs (LT-HSCs) express the lowest levels, which rise in multipotent progenitors. Within LT-HSCs themselves CUX1 levels vary from low to high.

Functional assays revealed that these differences are biologically meaningful. HSCs expressing low levels of CUX1 (CUX1Dim) showed high stemness and self-renewal potential, whereas those expressing high levels (CUX1Bright) only supported short-term engraftment. Thus, CUX1 dosage finely tunes HSC fate with low levels preserving stemness, whereas high levels promote differentiation. Using shRNA targeting CUX1, Martinez et al demonstrate that HSCs retain latent plasticity regulated by CUX1 in a dose-dependent manner, reducing CUX1 in CUX1Bright progenitors restores long-term engraftment, whereas knockdown in CUX1Dim cells further enhances self-renewal. Single-cell RNA sequence demonstrated that CUX1 shapes early differentiation trajectories, and that these effects are reversible upon CUX1 repression, revealing a dedifferentiation capacity, not previously described in normal hematopoiesis.

To investigate underlying mechanisms, Martinez et al combined transcriptomic and chromatin profiling. Compared with CUX1Bright HSCs, CUX1Dim cells express higher levels of stemness and antiviral programs, whereas genes linked to cell cycle and metabolism were repressed. Chromatin analysis showed that CUX1 silences stemness- and inflammation-associated loci during differentiation. Knocking-down CUX1 in CUX1Bright cells restored the transcriptome and chromatin state of CUX1Dim HSCs, confirming reprogramming toward a stem-like identity.

A striking observation was the consistent coactivation of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) with stem cell identity genes upon CUX1 downregulation, in the absence of any inflammatory stimuli. This raised the possibility that CUX1 regulates this HSC-intrinsic innate antiviral program through control of ERE expression. EREs, which constitute nearly half of mammalian genomes, include endogenous retroviruses (ERVs) and long and short interspersed nuclear elements (LINEs, SINEs, respectively). Their expression produces double-stranded RNA, cytoplasmic DNA, or DNA:RNA hybrids, sensed as parasitic nucleic acids by RIG-I–like receptors or the cyclic GMP-AMP synthase/stimulator of interferon response CGAMP interactor (cGAS/STING) pathway. This leads to activation of interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) and nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) pathways required for induction type I interferon (IFN).2 HSCs, unlike mature cells, display strong IFN-independent ISG expression, which correlates with high ERE activity, suggesting a functional link.3,4 This is consistent with earlier work showing that during embryonic hematopoiesis, EREs activate RIG-I–like receptors to drive inflammatory signals essential for HSC development.5 Building on this, Martinez et al demonstrate that CUX1 represses EREs by recruiting the methyltransferase EHMT2 to deposit the H3K9me2 repressive mark at ERE loci. Loss of CUX1 reactivates EREs, particularly ERVs, thereby triggering antiviral responses (see figure).

CUX1 levels finely regulate HSC fate: low levels maintain stemness, whereas high levels drive differentiation. HSCs retain latent plasticity and can reacquire stemness when CUX1 is reduced. This process involves controlled derepression of EREs, which activates antiviral innate immune signaling to promote self-renewal. The figure was created with BioRender.com. Porteu F. (2025) https://app.biorender.com/illustrations/68a77f0aa4f8865f0afd098e.

CUX1 levels finely regulate HSC fate: low levels maintain stemness, whereas high levels drive differentiation. HSCs retain latent plasticity and can reacquire stemness when CUX1 is reduced. This process involves controlled derepression of EREs, which activates antiviral innate immune signaling to promote self-renewal. The figure was created with BioRender.com. Porteu F. (2025) https://app.biorender.com/illustrations/68a77f0aa4f8865f0afd098e.

A critical finding of the Martinez et al study was that, the HSC-intrinsic ERE–ISG pathway is required for the enhanced self-renewal seen with CUX1 knockdown. Blocking ERE reverse transcription or STING/TBK1 signaling abolished this effect. Moreover, IRF1, a transcription factor essential for HSC function and inflammatory signaling, was required for reprogramming induced by CUX1 knockdown. These results underscore the central role of antiviral and inflammatory genes in HSC biology, consistent with earlier evidence that signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1), IFN-α, and ISGs support HSC self-renewal, protect against DNA damage and myelosuppression, and promote embryonic HSC development.4-7 Yet this contrasts with studies showing that infection-driven or exogenous IFN treatment induce HSC proliferation, differentiation, or attrition.6 These differences may be due to the presence or absence of specific ISGs and/or in the strength, duration, and cellular context of ISG activation, with intrinsic signaling in HSCs having protective effects, unlike widespread inflammation in the niche leading to more damaging outcomes.

The mechanisms by which ERE-induced immune responses promote self-renewal remain to be elucidated. One possibility is that ISG-mediated antiproliferative effects help preserve quiescence and thereby HSC potential. Yet EREs are not exclusively beneficial to HSCs: their accumulation with age and stress impairs HSC function.4,8 Interestingly, ISGs themselves can restrict ERE activity and limit LINE-1 propagation, safeguarding genomic integrity against both endogenous and viral threats.3,4 Elevated intrinsic ISG expression in HSCs may therefore enhance resilience during transplantation or viral challenge. Supporting this, thrombopoietin, a key regulator of HSC self-renewal, restricts ERE activity and limit LINE-1 propagation by activating a type I IFN-like pathway that induces strong ISG expression in HSCs.4

Finally, Martinez et al show that ERE and IFN responses are also upregulated in CUX1-deficient AML cells. Recent studies demonstrate that the ERV transcriptome defines HSCs and distinguishes them from progenitors, mature cells, and AML cells of different origin.9,10 Beyond serving as lineage markers, EREs may act as regulatory hubs for transcription factors that sustain quiescence and self-renewal. Understanding how CUX1Dim and CUX1Bright populations evolve with age, stress, and in myeloid malignancies may clarify the balance between the protective and deleterious roles of ERE-driven immune responses in HSC biology and leukemogenesis.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal