In this issue of Blood, Zhang et al1 provide extensive insight into the aging megakaryocytic niche and its influence on the age-associated decline in hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) and progenitor cell function. This study shows the critical role that megakaryocytic produced platelet factor 4 (PF4) has in maintaining young HSC phenotypes and the effects of its diminishing expression in aged mice. Intriguingly, the authors show that some age-associated effects on HSCs can be partially reversed by direct manipulation of PF4 availability.

HSC aging is associated with dysfunction and increased prevalence of hematologic disorders, such as neoplasia and deficient immune responses.2 In HSCs, age is accompanied by intrinsic cellular deregulation, such as alterations to the genome, epigenome, and transcriptome.3 Several recent studies have also demonstrated a role for the aging hematopoietic niche in modulating HSC function via extrinsic mechanisms. The hematopoietic niche is significantly altered as an organism ages, showing changes in cell numbers, cellular distribution, and organization.4 The megakaryocytic niche specifically changes with age, exhibiting altered megakaryocyte progenitor cell function and reduced interactions with HSCs.5 However, whether the megakaryocytic niche influences HSC aging and the mechanisms by which megakaryocytes exert this influence remain poorly understood.

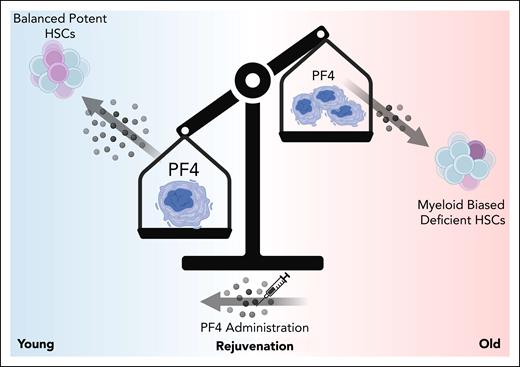

Here, the authors demonstrated that the mouse megakaryocytic niche exhibits aging-related changes that significantly impact the function of bone marrow–resident HSCs. They showed that the megakaryocytic niche is remodeled as mice age and that megakaryocytes display age-dependent changes in expression of inflammatory, cell-cycle, and autoregulatory genes. Many previous studies have shown that compared with young HSCs, aged HSCs are increased in number but display deficiencies in their ability to repopulate a balanced hematopoietic system.6 Interestingly, the authors show here and in a previous study that depleting megakaryocytes induces an increase in platelet-biased HSC number but a decrease in in vivo repopulating capacity in young mice, similar to what is seen in the context of aging. In contrast, old mice show a muted increase in HSC number with no change in in vivo repopulating ability upon megakaryocyte depletion. Together, the data suggest that the aged megakaryocytic niche may contribute to age-associated defects in HSCs. Mechanistically, the authors focused on PF4, an autoregulatory protein secreted by megakaryocytes. Interestingly, their data reveal that genetic deletion of PF4 leads to aging-associated phenotypes in young HSCs. Remarkably, direct PF4 administration to old mice partially rejuvenates the homeostatic hematopoietic system and HSC function in models of transplantation, significantly improving the repopulating frequency and capacity of aged HSCs. Genetic knockout approaches reveal that PF4 effects on young HSCs are at least partially mediated by cell-surface receptors LDLR and CXCR3. The story finishes with a critical punchline; that PF4 can also mitigate age-associated decline in function in human bone marrow–derived HSCs from middle-aged and older donors. In summary, the authors show that megakaryocytic produced PF4 is a critical regulatory factor that maintains young HSC phenotypes, making it a viable target to mitigate aging-associated disease onset (see figure).

In young mice, megakaryocytes produce PF4, which in turn drives the maintenance of lineage-balanced, potent HSCs. During aging, the megakaryocytic niche is altered. Megakaryocytes undergo changes in morphology, changes in number, and produce significantly less PF4. This reduction in PF4 contributes to myeloid-biased hematopoiesis and a loss of functionally potent HSCs. Both human and mouse HSC function can be partially restored through direct administration/treatment of recombinant PF4 protein.

In young mice, megakaryocytes produce PF4, which in turn drives the maintenance of lineage-balanced, potent HSCs. During aging, the megakaryocytic niche is altered. Megakaryocytes undergo changes in morphology, changes in number, and produce significantly less PF4. This reduction in PF4 contributes to myeloid-biased hematopoiesis and a loss of functionally potent HSCs. Both human and mouse HSC function can be partially restored through direct administration/treatment of recombinant PF4 protein.

A noteworthy aspect of this study is that PF4 administration to old HSCs did not fully recapitulate youthful hematopoiesis. This may be, as indicated by the authors, related to dosing. However, it could also indicate that there are parallel, PF4-independent mechanisms that also drive age-related changes. Indeed, another cell type that notably exerts extrinsic effects on HSCs during aging are mesenchymal stromal cells.4 Additionally, HSCs and hematopoietic progenitors are known to secrete proteins that may function in an autocrine manner. To our knowledge, there are no studies specifically demonstrating that the primitive hematopoietic secretome is altered with aging.7 It is highly likely, given the nearly universal impact of age has on HSC function, that at least some autoregulatory factors produced by stem and progenitor cells are changed.7 Further, as stated by the authors, age-associated changes are not restricted to just changes in cell number or expression of specific molecular programs. Rather, the niche also undergoes alterations in cellular distribution and morphology.8 Thus, there are other factors resulting from this remodeling that may impact cellular function, such as differences in cell-to-cell contacts and changes in the vasculature that may alter the bone marrow oxygenation gradient. Changes in local oxygenation may be of particular interest given the importance of the hypoxic niche to HSC function.9 To understand how to best mitigate diseased phenotypes brought on by age, it will be critical to understand how these various extrinsic factors are integrated with the intrinsic effects of aging to lead to the deficient phenotypes associated with old HSCs. In doing so, perhaps a combination of PF4 with other treatments will be elucidated to fully rejuvenate aged hematopoiesis.

Interestingly, PF4 shows promise as an engraftment-promoting factor for aged human HSCs in mouse models of bone marrow transplantation following ex vivo cell culture. A critical limitation of therapies requiring ex vivo manipulation is the culture-induced loss of HSC function. Thus, factors such as PF4 could be used in translational applications where bone marrow or mobilized peripheral blood are grown ex vivo, such as for use in gene editing. There also may be interest in testing the effects of PF4 in the context of expanded umbilical cord blood transplantation, which is a way to make cord blood transplantation more efficacious when it is limited by cell numbers. At first thought, it would be unexpected for PF4 to function similarly on the relatively young umbilical cord blood HSCs. However, ex vivo culture may age cells artificially, thus PF4 may prevent this artificial loss of function.10 The addition of PF4 to existing expansion techniques should be explored. Future studies should also elucidate the receptors that mediate PF4 rejuvenation of aged human HSCs, which will yield further insight into how this axis of regulation can be efficiently targeted for hematopoietic rejuvenation.

Overall, Zhang et al have shed light on a new mechanism that gets us closer to understanding the complex nature of hematopoietic aging and that may represent a unique therapeutic opportunity.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal