AMIS-inducing antibodies trigger in vivo RBC antigen and membrane loss independent of clearance.

AMIS-inducing antibodies, including anti-D, trigger in vitro RBC antigen loss and membrane transfer to macrophages through trogocytosis.

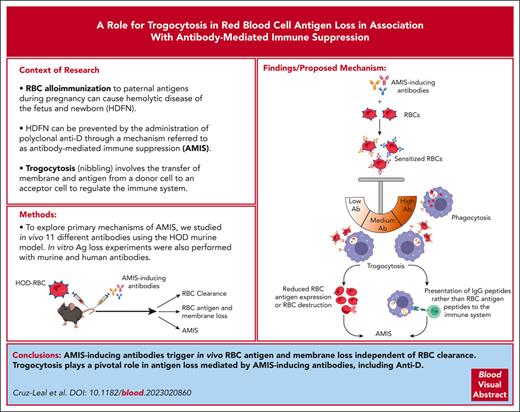

Visual Abstract

Red blood cell (RBC) alloimmunization to paternal antigens during pregnancy can cause hemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn (HDFN). This severe and potentially fatal neonatal disorder can be prevented by the administration of polyclonal anti-D through a mechanism referred to as antibody-mediated immune suppression (AMIS). Although anti-D prophylaxis effectively prevents HDFN, a lack of mechanistic clarity has hampered its replacement with recombinant agents. The major theories behind AMIS induction in the hematologic literature have classically centered around RBC clearance; however, antigen modulation/loss has recently been proposed as a potential mechanism of AMIS. To explore the primary mechanisms of AMIS, we studied the ability of 11 different antibodies to induce AMIS, RBC clearance, antigen loss, and RBC membrane loss in the HOD (hen egg lysozyme–ovalbumin–human Duffy) murine model. Antibodies targeting different portions of the HOD molecule could induce AMIS independent of their ability to clear RBCs; however, all antibodies capable of inducing a strong AMIS effect also caused significant in vivo loss of the HOD antigen in conjunction with RBC membrane loss. In vitro studies of AMIS-inducing antibodies demonstrated simultaneous RBC antigen and membrane loss, which was mediated by macrophages. Confocal live-cell microscopy revealed that AMIS-inducing antibodies triggered RBC membrane transfer to macrophages, consistent with trogocytosis. Furthermore, anti-D itself can induce trogocytosis even at low concentrations, when phagocytosis is minimal or absent. In view of these findings, we propose trogocytosis as a mechanism of AMIS induction.

Introduction

Hemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn (HDFN) is an alloimmune condition in which maternal antibodies specific to red blood cell (RBC) antigens cross the placenta and cause fetal RBC destruction or suppression of RBC erythropoiesis. HDFN can exhibit a range of symptoms and, in the most severe cases, neonatal death.1 Most clinically significant HDFN cases are associated with alloantibodies against blood group antigens from the Rh, Kell, Kidd, Duffy, and MNS families.2 Avoiding the development of maternal alloantibodies against incompatible fetal RBC antigens is the goal of effective therapy to prevent HDFN. The ability of antibodies to prevent an antigen-specific immune response can be referred to as antibody-mediated immune suppression (AMIS), with anti-D being a well-known clinical example of this phenomenon. Although anti-D prophylaxis successfully reduces the incidence of HDFN to 0.3%,3 the mechanism of action remains unsolved.

Several mechanisms of action have been proposed to explain AMIS, including RBC clearance, epitope masking/steric hindrance, antibody-mediated immune deviation, immunoglobulin G (IgG) glycosylation, cytokine effects, and others.4-8 Rapid RBC clearance, a widely accepted mechanism for AMIS induction, suggests that RhD+ fetal RBCs are opsonized by anti-D and eliminated through phagocytosis. This prevents antigen recognition by the immune system and, consequently, the generation of an antigen-specific antibody response. In the clinic, the ability of anti-D to remove RhD+ RBCs is the standard goal for immunoprophylaxis.9 Although several RhD-specific monoclonal antibodies have been developed based on their RBC clearance capabilities,10,11 their success has been limited.12 Moreover, murine studies have demonstrated that antibodies are able to induce AMIS without needing to clear the RBCs,13 suggesting that RBC clearance is unlikely to be the exclusive mechanism of AMIS.

More recently, antigen loss has been proposed as a possible mechanism of AMIS,14-16 with studies indicating that antibodies capable of removing the antigen from the RBC surface can prevent alloimmunization. In this context, antigen loss was an antigen-specific17 but not an epitope-specific process.15 The roles of the receptors for the Fc portion of IgG (FcγRs) and complement in RBC antigen loss under AMIS conditions have also been explored.14,18,19 The findings indicated that RBC antigen loss could occur in an FcγR-dependent13 or -independent18 manner, depending on the attributes of the antibody and/or antigen targeted. In addition, Sullivan et al showed that RhD antigen loss occurred in a patient with immune thrombocytopenic purpura who received anti-D20; however, this capacity has not yet been assessed in the AMIS context.

Antigen loss has been abundantly studied in monoclonal antibody-based cancer therapy.21 In this context, FcγRs on effector cells can mediate the process through a mechanism known as trogocytosis21 (gnawing or nibbling), which is characterized by the transfer of membrane fragments and associated antigen from a donor cell to an acceptor cell. Several immune cells, including T cells, B cells,22 basophils,23 neutrophils,24 natural killer cells,25 and macrophages/monocytes are able to mediate trogocytosis mediated by FcγR and many other molecules.21

The role of antigen loss in AMIS has only been assessed in scenarios in which the AMIS-inducing antibodies can cause both antigen loss and RBC clearance14,15 or epitope masking.17,18 Consequently, the relevance of antigen loss as a valid mechanism of AMIS without other potential confounders is yet to be defined. Here, we studied the ability of 11 different antibody variants to induce AMIS, RBC clearance, antigen loss, and RBC membrane loss using the HOD (hen egg lysozyme [HEL]–ovalbumin [OVA]–human Duffy [Duffy]) mouse model. Antibody-induced antigen loss was associated with AMIS and occurred independent of RBC clearance. In vitro experiments with anti-D demonstrated its ability to induce all of the major attributes of trogocytosis, including RBC membrane loss and membrane transfer to the macrophages, in which macrophages internalize small RBC membrane fragments. Together, this work supports the concept that RBC antigen loss through trogocytosis should be considered a major potential mechanism of AMIS.

Materials and methods

For more information, see supplemental Materials and Methods, available on the Blood website.

Mice

C57BL/6 mice and severe combined immunodeficient mice were from The Jackson Laboratory (ME). HOD mice expressing the transgenic RBC-specific recombinant protein (HOD) comprised HEL, OVA, and Duffy and were generously donated by James C. Zimring.13

Antibodies

The HEL-specific mouse polyclonal IgG (pIgG anti–HEL) was produced in our laboratory as described previously,26 and the HEL-specific monoclonal antibodies 4B7 (IgG1), 2F4 (IgG1), and GD7 (IgG2b) were produced at BioXCell (NH) for James C. Zimring, who kindly gifted them to us. Mouse pIgG anti–OVA was manufactured in house.26 The Duffy-specific monoclonal antibodies (mouse anti-Fy3) MIMA29 (IgG2a) and CBC-512 (IgG1)27 were generously provided by Marion Reid and Gregory Halverson of the New York Blood Center and Makoto Uchikawa from the Japanese Red Cross Kanto-Koshinetsu Block Blood Center respectively. Deglycosylated variants of antibodies were synthesized as described.28 TER-119 and CBC-512 were subclass-switched to a mouse IgG2a, as detailed.29 OVA-specific rabbit pIgG and all control antibodies were from commercial suppliers. Anti-D was WinRho SDF.

Transfusion and AMIS induction

HOD-RBCs were labeled with the membrane dye PKH26 (PKH26+HOD-RBCs).15 Mice were transfused with 108 PKH26+HOD-RBCs, which represents ∼1% of the total RBCs in the murine circulation and is equivalent to a 50 mL bleed in humans,30 and then injected with the indicated quantities of antibodies against different portions of HOD antigen 18 hours after RBC transfusion. Serum was collected on day 7, corresponding to the maximum IgM and IgG response.13,31

Detection of the HEL-specific antibody response, RBC clearance, and in vivo RBC antigen and membrane loss

The HEL-specific IgM and IgG responses and RBC clearance were evaluated by enzyme-linked immunosorbent essay and flow cytometry, as described.15 Surface levels of the HEL-, OVA-, and Duffy antigen on the surviving PKH26+HOD-RBCs 2 hours before and 2 hours and 24 hours after antibody injection were also evaluated as described.15 The median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the PKH26 signal on the recovered PKH26+HOD-RBCs at each time point was also determined and expressed as the percentage initial MFI (before antibody injection).

Macrophage culture

Mouse RAW 264.7 macrophages (RAW macrophages), bone marrow-derived macrophages (BM macrophages), and THP-1-CD16A cells were cultured and obtained as described previously.32-35 Briefly, BM cells were plated in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum and 10 ng/mL of mouse macrophage colony-stimulating factor recombinant protein (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 5 days. On day 6, the attached cells were harvested and used in further experiments.

RBC sensitization

HOD-RBCs and PKH67+HOD-RBCs were incubated with pIgG anti–HEL, anti-Duffy monoclonal antibodies (MIMA29 and CBC-512, and IgG2a), TER-119 IgG2a, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), or the isotype controls (IgG2a or normal pIgG) at 5 μg/mL for 1 hour at 22°C. Rhesus D antigen–positive human RBCs (RhD+-hRBCs) or labeled with PKH67 (PKH67+RhD+-hRBCs) were incubated for 30 minutes with control IgG or anti-D starting at 1770 ng/ml (0.885 IU). Mouse and human RBCs were used to perform phagocytosis or in vitro antigen-loss experiments.

In vitro RBC antigen and membrane loss

RAW macrophages or BM macrophages were seeded in a 12-well polystyrene plate and incubated with sensitized or nonsensitized PKH67+HOD-RBCs (macrophages / RBC, 1:5) for 30 minutes and 3 hours at 37°C, 5% CO2. RBC and macrophages incubated alone were used as controls. After incubation, wells were washed to recover noninternalized PKH67+HOD-RBCs. Surface levels of the HEL- and Duffy antigen on the recovered PKH67+HOD-RBCs were assessed as described,15 but using an allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated goat anti–mouse IgG secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratory Inc). The cells were analyzed by flow cytometry on a Becton Dickinson Life Science Research Fortessa-X20, and the MFI of the APC signal on PKH67+HOD-RBCs was determined. RBC membrane loss was evaluated by measuring the loss of the PKH67 signal on PKH67+HOD-RBCs recovered.

THP-1-CD16A cells were seeded at 2.5 × 105 cells per well in a 24-well polystyrene plate. After 48 hours of culture and differentiation as described,35 the media was replaced, and 25 × 105 sensitized or nonsensitized PKH67+RhD+-RBCs were added per well. Following the protocol described earlier with HOD-RBC, hRBC membrane loss and PKH67 signal uptake by THP-1-CD16A cells were determined.

Macrophages incubated with sensitized and nonsensitized RBCs as well as nonstimulated macrophages were washed thrice followed by hypotonic lysis with 2 more washes with PBS. The percentage of PKH67+ macrophages and their MFI in the PKH67 signal were determined by flow cytometry.

Phagocytosis

Phagocytosis experiments with anti-D, human RBCs, and THP-1-CD16A as phagocytic cells were performed following the protocol mentioned earlier.

Confocal and live-cell imaging

RAW macrophages were seeded on coverslips for 2 days and maintained in complete RPMI at 37°C and 5% CO2. PKH67+HOD-RBCs were incubated with pIgG anti–HEL, anti-Duffy CBC-512 IgG2a, or PBS; washed; and incubated with macrophages at 37°C and 5% CO2. After 3 hours, excess RBCs were washed away and external RBCs lysed, followed by fixation and imaging on a Quorum multimodal imaging system (spinning disk confocal; Quorum Technologies, ON, Canada). Similar confocal experiments were performed using THP-1-CD16A cells and PKH67+RhD+-hRBC nonsensitized or sensitized with anti-D. RAW macrophages (3 × 105 cells per well) were seeded on glass coverslips in the wells of a 12-well plate in complete RPMI overnight. Macrophages were transfected with 500 ng per well of plasmid expressing LifeAct monomeric red fluorescent protein36 via lipofectamine LTX with Plus (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc) for 5 hours. Twenty-four hours after transfection, macrophages on coverslips were transferred to a chamlide magnetic imaging chamber and placed into a warmed chamber at 37°C on the stage of a spinning disk confocal microscope. A total of 25 × 105 nonsensitized or sensitized PKH67+HOD-RBCs were added to the macrophages, and images were taken with Z-stacking. For more details, see supplemental Information.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 8 software (San Diego, CA). The normal distribution and the homogeneity of the variance of the data were determined. Data not normally distributed or without equality of variance were analyzed using a nonparametric test. The specific tests used in each comparison are described in the figure legends. The correlation between the HEL-specific IgM response and the percentage of antigen loss was determined using Spearman correlation.

Results

Antibodies targeting the HOD antigen can induce AMIS by triggering RBC antigen loss without RBC clearance

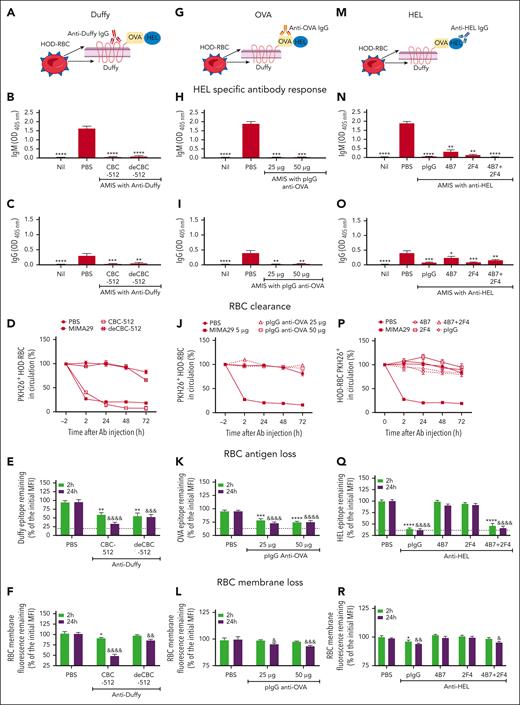

To determine whether the ability of antibodies to induce RBC clearance can be uncoupled from their ability to induce AMIS, C57BL/6 mice transfused with PKH26+HOD-RBCs were injected with anti-Duffy CBC-512 wild-type antibody or its deglycosylated variant (deCBC-512; Figure 1A), a mouse pIgG anti–OVA (Figure 1G), or anti-HEL mouse polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies (Figure 1M).

HOD-specific antibodies can cause AMIS by inducing RBC antigen loss rather than RBC clearance. (A,G,M) Schematic representation of HOD-RBC with antibodies specific for each antigen portion. C57BL/6 mice were transfused with 108 PKH26+HOD-RBCs. Twenty-four hours later, mice were injected with antibodies specific for (A-F) Duffy, (G-L) OVA, and (M-R) HEL portions of the HOD antigen. The quantity of each antibody evaluated was 5 μg of anti-Duffy antibody CBC-512 wild-type or its deglycosylated variant (deCBC-512); 25 and 50 μg of a mouse pIgG specific to OVA; 5 μg of the HEL-specific mouse pIgG; and monoclonal antibodies 4B7, 2F4, or a blend of 4B7 and 2F4 recognizing non–crossblocking epitopes (4B7 + 2F4) (2.5 μg each). Mice injected with PBS were used as an alloimmunization controls. The HEL-specific (B,H,N) IgM and (C,I,O) IgG response on day 7 were evaluated by enzyme-linked immunosorbent essay. Data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of the optical density at 405 nm (OD 405nm). (D,J,P) The percentage of PKH26+HOD-RBCs in circulation 2 hours before (time = −2) and after antibody injection, as indicated. Transfused mice injected with 5 μg of anti-Duffy monoclonal antibody MIMA29 were used as a positive controls for RBC clearance. The MFI signal of the Duffy (E), OVA (K), and HEL (Q) epitope from the recovered cells from recipient mice injected with antibodies specific against each antigen (or PBS) was determined by ex vivo incubation of the cells with additional anti-Duffy CBC-512, pIgG anti–OVA, or pIgG anti–HEL respectively, followed by fluorescein isothiocyanate–labeled anti–mouse IgG. The remaining level of Duffy, OVA, and HEL epitopes at 2 and 24 hours after antibody injection was expressed as a percentage of the initial MFI before antibody injection. The dotted line indicates the MFI of the fluorescein isothiocyanate signal of cells incubated only with the secondary antibody, expressed as percentage of the initial MFI. RBC membrane loss induced by (F) anti-Duffy, (L) anti-OVA, and (R) anti-HEL antibodies was measured as the MFI of the PKH26 signal from cells recovered at each time point and expressed as the percentage initial MFI. Data in all panels represent the mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments with the total number of mice per group as (B-F) PBS: (n = 9), CBC-512: (n = 7), deCBS-512: (n = 9), and nil; (n = 6); (H-L) PBS: (n = 8), pIgG anti–OVA 25 μg, (n = 10), 50 μg, (n = 10), and nil: (n = 8); and (N-R) PBS: (n = 14), pIgG anti–HEL: (n = 14), 4B7: (n = 10), 2F4: (n = 8), 4B7 + 2F4: (n = 8), and nil: (n = 10). Statistical significance compared with that of the positive control for alloimmunization (PBS) was determined using Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn post hoc test in graphs of panels B,C,H,I,N,O. Data represented in graphs of panels E,F,K,L by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and panels Q,R by mixed-effects analysis with Dunnett multiple comparisons test for all of them. ∗ and & indicate significant differences to the control group (PBS) at 2 hours and 24 hours, respectively. (∗P = .05; ∗∗P = .01; ∗∗∗P = .001; ∗∗∗∗P = .0001 and &P = .05; &&P = .01; &&&P = .001; &&&&P = .0001). Panels A,G,M were created with BioRender.com.

HOD-specific antibodies can cause AMIS by inducing RBC antigen loss rather than RBC clearance. (A,G,M) Schematic representation of HOD-RBC with antibodies specific for each antigen portion. C57BL/6 mice were transfused with 108 PKH26+HOD-RBCs. Twenty-four hours later, mice were injected with antibodies specific for (A-F) Duffy, (G-L) OVA, and (M-R) HEL portions of the HOD antigen. The quantity of each antibody evaluated was 5 μg of anti-Duffy antibody CBC-512 wild-type or its deglycosylated variant (deCBC-512); 25 and 50 μg of a mouse pIgG specific to OVA; 5 μg of the HEL-specific mouse pIgG; and monoclonal antibodies 4B7, 2F4, or a blend of 4B7 and 2F4 recognizing non–crossblocking epitopes (4B7 + 2F4) (2.5 μg each). Mice injected with PBS were used as an alloimmunization controls. The HEL-specific (B,H,N) IgM and (C,I,O) IgG response on day 7 were evaluated by enzyme-linked immunosorbent essay. Data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of the optical density at 405 nm (OD 405nm). (D,J,P) The percentage of PKH26+HOD-RBCs in circulation 2 hours before (time = −2) and after antibody injection, as indicated. Transfused mice injected with 5 μg of anti-Duffy monoclonal antibody MIMA29 were used as a positive controls for RBC clearance. The MFI signal of the Duffy (E), OVA (K), and HEL (Q) epitope from the recovered cells from recipient mice injected with antibodies specific against each antigen (or PBS) was determined by ex vivo incubation of the cells with additional anti-Duffy CBC-512, pIgG anti–OVA, or pIgG anti–HEL respectively, followed by fluorescein isothiocyanate–labeled anti–mouse IgG. The remaining level of Duffy, OVA, and HEL epitopes at 2 and 24 hours after antibody injection was expressed as a percentage of the initial MFI before antibody injection. The dotted line indicates the MFI of the fluorescein isothiocyanate signal of cells incubated only with the secondary antibody, expressed as percentage of the initial MFI. RBC membrane loss induced by (F) anti-Duffy, (L) anti-OVA, and (R) anti-HEL antibodies was measured as the MFI of the PKH26 signal from cells recovered at each time point and expressed as the percentage initial MFI. Data in all panels represent the mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments with the total number of mice per group as (B-F) PBS: (n = 9), CBC-512: (n = 7), deCBS-512: (n = 9), and nil; (n = 6); (H-L) PBS: (n = 8), pIgG anti–OVA 25 μg, (n = 10), 50 μg, (n = 10), and nil: (n = 8); and (N-R) PBS: (n = 14), pIgG anti–HEL: (n = 14), 4B7: (n = 10), 2F4: (n = 8), 4B7 + 2F4: (n = 8), and nil: (n = 10). Statistical significance compared with that of the positive control for alloimmunization (PBS) was determined using Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn post hoc test in graphs of panels B,C,H,I,N,O. Data represented in graphs of panels E,F,K,L by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and panels Q,R by mixed-effects analysis with Dunnett multiple comparisons test for all of them. ∗ and & indicate significant differences to the control group (PBS) at 2 hours and 24 hours, respectively. (∗P = .05; ∗∗P = .01; ∗∗∗P = .001; ∗∗∗∗P = .0001 and &P = .05; &&P = .01; &&&P = .001; &&&&P = .0001). Panels A,G,M were created with BioRender.com.

Deglycosylation of the CBC-512 (IgG1) did not affect its ability to induce AMIS (Figure 1B-C) but completely abrogated its ability to clear HOD-RBCs (Figure 1D). Interestingly, both antibodies, CBC-512 and deCBC-512, were able to induce Duffy-epitope loss (Figure 1E) and significant RBC membrane fluorescence loss (Figure 1F). CBC-512 induced similar magnitudes of RBC clearance and antigen loss in both severe combined immunodeficient mice and C57BL/6 mice (supplemental Figure 1), suggesting that RBC antigen and membrane loss occurs independently of functional T and B lymphocytes and may be mediated by innate immune cells.

The mouse pIgG anti–OVA, composed predominantly of IgG2b and IgG2a (supplemental Figure 2A-B), prevented the HEL-specific IgM and IgG response (Figure 1H-I) at doses capable of saturating 107 HOD-RBCs in vitro (supplemental Figure 2C-D). Although the antibody did not induce any measurable RBC clearance (Figure 1J), it provoked significant OVA-epitope loss and RBC membrane fluorescence loss, both attributes of trogocytosis,37 in the circulating RBCs (Figure 1K-L).

HEL-specific antibodies can induce AMIS-independent clearance of HOD-RBCs.13,18 Here, we evaluated the ability of HEL-specific antibodies to induce trogocytosis (RBC antigen and membrane loss). In line with published results,13,17,18,31,38 all anti-HEL antibodies induced significant suppression of the IgM and IgG response (Figure 1N-O). However, none of the anti-HEL antibodies triggered HOD-RBC clearance (Figure 1P). Importantly, all anti-HEL antibodies induced some level of HEL epitope loss from the RBC surface, with pIgG anti–HEL and the blend of monoclonal antibodies causing the most extensive antigen loss (Figure 1Q). The pIgG anti–HEL and the blend of monoclonal antibodies also caused RBC membrane fluorescence loss, although membrane loss did not reach statistical significance for the single monoclonal antibodies (Figure 1R).

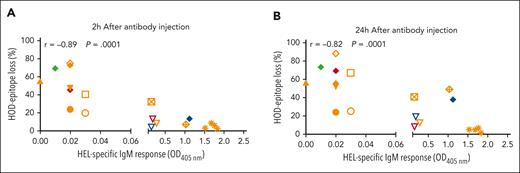

Overall, we evaluated a panel of 11 antibodies specific against different portions of the HOD antigen (Table 1; supplemental Figure 3). The antibodies induced AMIS without necessarily clearing the HOD-RBCs. In contrast, all antibodies that provoked AMIS caused at least some level of antigen loss, independent of their specificity (Table 2; supplemental Figures 4 and 5), and there was a strong correlation between the degree of AMIS and the degree of antigen loss for the antibodies (r = −0.8; P = .0001; Figure 2).

A panel of monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies specific to different portions of the HOD antigen and their characteristics

| No. . | Antibodies . | Specificity . | IgG subtype . | RBC binding . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mouse pIgG anti–HEL | HEL | Polyclonal | +++ |

| 2 | 4B7 | HEL | IgG1 | ++ |

| 3 | 2F4 | HEL | IgG1 | ++ |

| 4 | GD7 | HEL | IgG2b | ++ |

| 5 | 4B7 + 2F4 | HEL | IgG1 blend | +++ |

| 6 | Rabbit pIgG anti–OVA | OVA | Polyclonal | +++++ |

| 7 | Mouse pIgG anti–OVA | OVA | Polyclonal∗ | ++ |

| 8 | MIMA29 anti-Duffy | Fy3 | IgG2a | +++++ |

| 9 | deMIMA29 | Fy3 | IgG2a | +++++ |

| 10 | CBC-512 anti-Duffy | Fy3 | IgG1 | +++++ |

| 11 | deCBC-512 | Fy3 | IgG1 | +++++ |

| No. . | Antibodies . | Specificity . | IgG subtype . | RBC binding . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mouse pIgG anti–HEL | HEL | Polyclonal | +++ |

| 2 | 4B7 | HEL | IgG1 | ++ |

| 3 | 2F4 | HEL | IgG1 | ++ |

| 4 | GD7 | HEL | IgG2b | ++ |

| 5 | 4B7 + 2F4 | HEL | IgG1 blend | +++ |

| 6 | Rabbit pIgG anti–OVA | OVA | Polyclonal | +++++ |

| 7 | Mouse pIgG anti–OVA | OVA | Polyclonal∗ | ++ |

| 8 | MIMA29 anti-Duffy | Fy3 | IgG2a | +++++ |

| 9 | deMIMA29 | Fy3 | IgG2a | +++++ |

| 10 | CBC-512 anti-Duffy | Fy3 | IgG1 | +++++ |

| 11 | deCBC-512 | Fy3 | IgG1 | +++++ |

HOD-RBCs, RBCs expressing a recombinant antigen composed of HEL, OVA sequences comprising amino acids 251 to 349, and the complete Duffy b (Fyb) transmembrane protein.

RBC binding: The maximum binding level reached for each antibody by flow cytometry and summarized based on the median fluorescence intensity (MFI) values calculated: MFI 50 to 200 (+), MFI: 200 to 400 (++), MFI 400 to 1000 (+++), MFI 1000 to 2000 (++++), and MFI > 2000 (+++++). See supplemental Figure 3.

Primarily consisting of mouse IgG2a and IgG2b (supplemental Figure 2).

Antibodies against the HOD antigen are able to induce AMIS independent of their ability to induce RBC clearance but related to their capacity to promote RBC antigen and membrane loss

|

|

AMIS: the degree to which each antibody inhibited the HEL-specific IgM response 7 days after HOD-RBC transfusion and expressed as percent inhibition of alloimmunization (–, <20%; +, 20%-49%; ++, 50%-69%; +++, 70%-89%; and ++++, >90%).

RBC clearance: the degree to which HOD-specific antibodies induced HOD-RBC clearance from the circulation in the recipient mouse. This was calculated based on the percentage of transfused PKH26+HOD-RBCs remaining in circulation in the recipient mouse in comparison with before antibody injection (–, <25%; +, 25%-35%; ++, 36%-49%; +++, 50%-69%; and ++++, >70%).

Antigen loss: the degree to which the antibody induced loss of the epitope from HOD-RBCs recovered from recipient mice 24 hours after antibody injection. This was calculated based on the percentage of antigen remaining on recovered HOD-RBCs (–, <5%; +, 5%-24%; ++, 25%-49%; +++, 50%-69%; and ++++, >70%).

RBC membrane loss: the degree to which the antibody induced loss of PKH26 membrane fluorescence from HOD-RBCs recovered 24 hours after antibody injection. Expressed as the percentage of membrane fluorescence lost (–, <2.4%; +, 2.5%-24%; ++, 25%-49%; +++, 50%-69%; and ++++, >70%).

N/T: not tested.

∗Symbols for each experimental group are explained in Figure 2.

†The results are shown in supplemental Figure 4.

‡The results are shown in supplemental Figure 5.

RBC antigen loss and AMIS induction are closely related. C57BL/6 mice were transfused with PKH26+HOD-RBC. Twenty-four hours later, mice received AMIS-inducing antibodies (Table 2), with the HEL-specific IgM response assessed on day 7. Mice injected with PBS instead of AMIS-inducing antibodies were used as a positive control for alloimmunization (100%) (orange asterisk). Correlation between AMIS activity and antigen loss induced at (A) 2 hours and (B) 24 hours was determined by Spearman test. The panel of anti-HOD antibodies assessed included anti-HEL pIgG (solid orange triangle), monoclonal 4B7 (open inverted orange triangle), 2F4 (open inverted red triangle), GD7 (open inverted blue triangle), and a blend of monoclonal (4B7 + 2F4) (filled inverted orange triangle), mouse pIgG anti–OVA at 25 μg (open orange circle), and 50 μg (filled orange circle), rabbit pIgG anti–OVA at 10 μg (filled blue diamond), 25 μg (filled red diamond), 50 μg (filled green diamond), and 75 μg (filled orange diamond), and anti-Duffy antibodies CBC-512 (open orange square), deglycosylated CBC-512 (crossed orange square), MIMA29 (open orange diamond), and deglycosylated MIMA29 (crossed orange diamond).

RBC antigen loss and AMIS induction are closely related. C57BL/6 mice were transfused with PKH26+HOD-RBC. Twenty-four hours later, mice received AMIS-inducing antibodies (Table 2), with the HEL-specific IgM response assessed on day 7. Mice injected with PBS instead of AMIS-inducing antibodies were used as a positive control for alloimmunization (100%) (orange asterisk). Correlation between AMIS activity and antigen loss induced at (A) 2 hours and (B) 24 hours was determined by Spearman test. The panel of anti-HOD antibodies assessed included anti-HEL pIgG (solid orange triangle), monoclonal 4B7 (open inverted orange triangle), 2F4 (open inverted red triangle), GD7 (open inverted blue triangle), and a blend of monoclonal (4B7 + 2F4) (filled inverted orange triangle), mouse pIgG anti–OVA at 25 μg (open orange circle), and 50 μg (filled orange circle), rabbit pIgG anti–OVA at 10 μg (filled blue diamond), 25 μg (filled red diamond), 50 μg (filled green diamond), and 75 μg (filled orange diamond), and anti-Duffy antibodies CBC-512 (open orange square), deglycosylated CBC-512 (crossed orange square), MIMA29 (open orange diamond), and deglycosylated MIMA29 (crossed orange diamond).

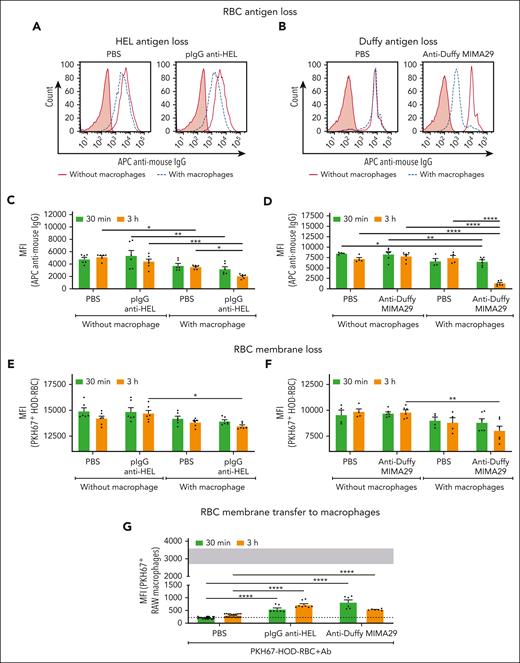

AMIS-inducing antibodies triggered in vitro RBC antigen loss and RBC membrane uptake by macrophages

Antibodies specific for the distal and proximal portions of the HOD molecule (HEL and Duffy) were selected to perform in vitro antigen- and membrane-loss experiments. Two AMIS-inducing antibodies, pIgG anti–HEL and monoclonal anti-Duffy (MIMA29), induced HEL and Duffy antigen loss, respectively, on the RBC surface after 30 minutes and 3 hours of incubation with RAW macrophages (Figure 3A-C). Loss of the HEL and OVA portions of the HOD molecule was also induced by MIMA29 (supplemental Figure 6), involving the removal of the whole antigen. RBC antigen loss did not occur in the absence of macrophages, demonstrating the requirement of these cells for the in vitro antigen loss process. Antigen loss occurred concurrently with RBC membrane loss, with both anti-HEL and anti-Duffy AMIS-inducing antibodies triggering significant RBC membrane loss after 3 hours of incubation, with more pronounced loss with anti-Duffy (Figure 3E-F). In addition, macrophages incubated with sensitized RBCs exhibited a significant increase in RBC membrane uptake compared with macrophages incubated with nonsensitized RBCs (Figure 3G; supplemental Figure 7).

AMIS-inducing antibodies promote RBC antigen loss, RBC membrane loss, and RBC membrane transfer to macrophages in vitro. HOD-RBCs fluorescently labeled with PKH67 (PKH67+HOD-RBC) and sensitized with anti-HEL pIgG or anti-Duffy MIMA29 IgG2a were incubated with or without RAW macrophages for 30 minutes or 3 hours at 37°C as indicated. Nonsensitized PKH67+HOD-RBCs (PBS) were used as negative controls. RBCs were recovered after incubation, and the residual external RBCs were lysed. The RBCs recovered from each condition were resensitized with additional pIgG anti–HEL or anti-Duffy MIMA29, followed by APC-labeled anti–mouse IgG and further analyzed by flow cytometry. Representative histograms of (A) HEL antigen and (B) Duffy antigen detected on the recovered RBCs after 3 hours of incubation with (dashed blue lines) or without (solid red line) macrophages. The filled red histogram represents the fluorescent RBC gate (ie, PKH67+HOD-RBC) incubated only with the secondary antibody. (C-D) Cumulative data depicting the median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of detectable (C) HEL antigen and (D) Duffy antigen on HOD-RBCs after incubation in the presence vs absence of macrophages. (E-F) MFI of the PKH67 signal of the PKH67+HOD-RBCs recovered as indicated. (G) Macrophages incubated with nonsensitized and sensitized RBCs were analyzed by flow cytometry, and the MFI of PKH67 from RBCs in the macrophage gate was determined. Gray-shaded area represents the MFI of PKH67 signal in the PKH67+ macrophages detected after incubation with RBCs sensitized with TER-119, an antibody that induces robust phagocytosis. The dotted line represents background fluorescence of macrophages without added RBCs. Statistical analyses of the data represented in graphs of panels C and E were performed by two-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons post hoc test, mixed-effects analysis with Tukey multiple comparisons post hoc test for panel D graph, and two-way ANOVA with Sidak multiple comparisons post hoc test for graphs of panels F and G (∗P = .05; ∗∗P = .01; ∗∗∗P = .001; ∗∗∗∗P = .0001).

AMIS-inducing antibodies promote RBC antigen loss, RBC membrane loss, and RBC membrane transfer to macrophages in vitro. HOD-RBCs fluorescently labeled with PKH67 (PKH67+HOD-RBC) and sensitized with anti-HEL pIgG or anti-Duffy MIMA29 IgG2a were incubated with or without RAW macrophages for 30 minutes or 3 hours at 37°C as indicated. Nonsensitized PKH67+HOD-RBCs (PBS) were used as negative controls. RBCs were recovered after incubation, and the residual external RBCs were lysed. The RBCs recovered from each condition were resensitized with additional pIgG anti–HEL or anti-Duffy MIMA29, followed by APC-labeled anti–mouse IgG and further analyzed by flow cytometry. Representative histograms of (A) HEL antigen and (B) Duffy antigen detected on the recovered RBCs after 3 hours of incubation with (dashed blue lines) or without (solid red line) macrophages. The filled red histogram represents the fluorescent RBC gate (ie, PKH67+HOD-RBC) incubated only with the secondary antibody. (C-D) Cumulative data depicting the median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of detectable (C) HEL antigen and (D) Duffy antigen on HOD-RBCs after incubation in the presence vs absence of macrophages. (E-F) MFI of the PKH67 signal of the PKH67+HOD-RBCs recovered as indicated. (G) Macrophages incubated with nonsensitized and sensitized RBCs were analyzed by flow cytometry, and the MFI of PKH67 from RBCs in the macrophage gate was determined. Gray-shaded area represents the MFI of PKH67 signal in the PKH67+ macrophages detected after incubation with RBCs sensitized with TER-119, an antibody that induces robust phagocytosis. The dotted line represents background fluorescence of macrophages without added RBCs. Statistical analyses of the data represented in graphs of panels C and E were performed by two-way ANOVA with Tukey multiple comparisons post hoc test, mixed-effects analysis with Tukey multiple comparisons post hoc test for panel D graph, and two-way ANOVA with Sidak multiple comparisons post hoc test for graphs of panels F and G (∗P = .05; ∗∗P = .01; ∗∗∗P = .001; ∗∗∗∗P = .0001).

To determine whether RBC antigen loss and membrane transfer could be replicated with primary macrophages, BM macrophages were studied. RBC antigen and membrane loss as well as RBC membrane transfer to the BM macrophages was observed. (supplemental Figure 8).

Although nonsensitized PKH67+HOD-RBCs exhibited some level of macrophage-mediated antigen loss (Figure 3A,C), this antibody-independent phenomenon appeared to be attributed to nonselective macrophage matrix metalloproteinase activity (supplemental Figure 9A). Importantly, the antibody-dependent antigen loss and membrane uptake by macrophages were not significantly affected by the matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor used (supplemental Figure 9B-C).

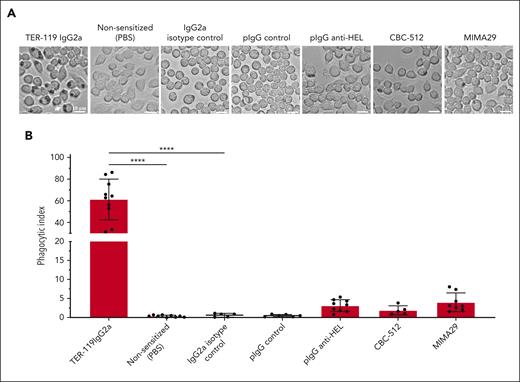

AMIS-inducing antibodies do not trigger significant macrophage phagocytosis of RBCs. PKH67+HOD-RBC were sensitized with TER119, which induces a robust level of phagocytosis.32 In comparison, additional RBCs were sensitized with anti-HOD antibodies (pIgG anti-HEL, or anti-Duffy CBC-512 IgG2a, or MIMA29 IgG2a), a mouse IgG2a isotype control, mouse pIgG nonspecific, or kept nonsensitized (PBS). RAW macrophages were stimulated with nonsensitized or sensitized RBC for 30 minutes at 37°C and 5% CO2. External, nonphagocytosed RBCs were removed by hypotonic (water) lysis. (A) Brightfield microscopy images of macrophages from each condition are shown. The white arrows indicate an example of macrophages with phagocytosed RBCs. Pictures are representative of 5 independent experiments. (B) The phagocytic index was calculated as the number of RBCs engulfed per 100 macrophages. Data represent the mean ± SEM of 5 independent experiments with total number of samples per group (n = 5-10). Statistical analyses of the data represented in the graph of panel B were performed by one-way ANOVA with Sidak multiple comparisons post hoc test (∗∗∗∗P = .0001).

AMIS-inducing antibodies do not trigger significant macrophage phagocytosis of RBCs. PKH67+HOD-RBC were sensitized with TER119, which induces a robust level of phagocytosis.32 In comparison, additional RBCs were sensitized with anti-HOD antibodies (pIgG anti-HEL, or anti-Duffy CBC-512 IgG2a, or MIMA29 IgG2a), a mouse IgG2a isotype control, mouse pIgG nonspecific, or kept nonsensitized (PBS). RAW macrophages were stimulated with nonsensitized or sensitized RBC for 30 minutes at 37°C and 5% CO2. External, nonphagocytosed RBCs were removed by hypotonic (water) lysis. (A) Brightfield microscopy images of macrophages from each condition are shown. The white arrows indicate an example of macrophages with phagocytosed RBCs. Pictures are representative of 5 independent experiments. (B) The phagocytic index was calculated as the number of RBCs engulfed per 100 macrophages. Data represent the mean ± SEM of 5 independent experiments with total number of samples per group (n = 5-10). Statistical analyses of the data represented in the graph of panel B were performed by one-way ANOVA with Sidak multiple comparisons post hoc test (∗∗∗∗P = .0001).

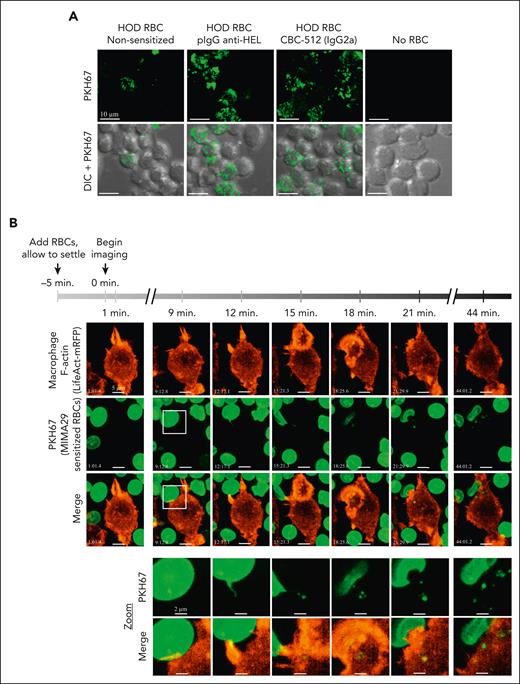

Interaction between macrophages and AMIS-inducing antibody sensitized RBCs triggers erythrocyte membrane nibbling by macrophages in vitro. (A) RAW macrophages were seeded on coverslips for 2 days and maintained in complete RPMI at 37°C and 5% CO2. PKH67+HOD-RBCs were opsonized with pIgG anti–HEL, anti-Duffy CBC-512 IgG2a, or kept nonsensitized (PBS) before incubation with macrophages at 37°C and 5% CO2. After 3 hours, excess RBCs were washed away, and external RBCs lysed followed by fixation and imaging on a Quorum multimodal imaging system (spinning disk confocal) under original magnification ×63 objective oil immersion (numerical aperture 1.47). Scale bar = 10 μm. (B) RAW macrophages were seeded on coverslips and, 1 day later, were transfected with a plasmid expressing the F-actin visualizing protein LifeAct monomeric red fluorescent protein. Twenty-four hours later, transfected macrophages were transferred to a chamlide chamber for confocal microscopy and PKH67+HOD-RBCs sensitized with anti-Duffy MIMA29 were added to the macrophages 5 minutes before imaging to allow the RBCs to reach the bottom. For areas where RBCs and macrophages appear to be in proximity, images were taken every 60 seconds for 45 minutes on a spinning disk confocal as above. Scale bar = 5 μm. The white square at the 9 minutes time point indicates the zoomed area (bottom 2 rows). Zoom: scale bar represents 2 μm. There was a higher apparent level of trogocytosis of RBC membrane fragments by macrophages using the confocal imaging with fixed samples (A) as compared with the LifeAct experiments (B). This is likely explained by the shorter incubation time for the LifeAct experiments (45 minutes vs 3 hours) and phototoxic effects of the repeated imaging for live-cell experiments.

Interaction between macrophages and AMIS-inducing antibody sensitized RBCs triggers erythrocyte membrane nibbling by macrophages in vitro. (A) RAW macrophages were seeded on coverslips for 2 days and maintained in complete RPMI at 37°C and 5% CO2. PKH67+HOD-RBCs were opsonized with pIgG anti–HEL, anti-Duffy CBC-512 IgG2a, or kept nonsensitized (PBS) before incubation with macrophages at 37°C and 5% CO2. After 3 hours, excess RBCs were washed away, and external RBCs lysed followed by fixation and imaging on a Quorum multimodal imaging system (spinning disk confocal) under original magnification ×63 objective oil immersion (numerical aperture 1.47). Scale bar = 10 μm. (B) RAW macrophages were seeded on coverslips and, 1 day later, were transfected with a plasmid expressing the F-actin visualizing protein LifeAct monomeric red fluorescent protein. Twenty-four hours later, transfected macrophages were transferred to a chamlide chamber for confocal microscopy and PKH67+HOD-RBCs sensitized with anti-Duffy MIMA29 were added to the macrophages 5 minutes before imaging to allow the RBCs to reach the bottom. For areas where RBCs and macrophages appear to be in proximity, images were taken every 60 seconds for 45 minutes on a spinning disk confocal as above. Scale bar = 5 μm. The white square at the 9 minutes time point indicates the zoomed area (bottom 2 rows). Zoom: scale bar represents 2 μm. There was a higher apparent level of trogocytosis of RBC membrane fragments by macrophages using the confocal imaging with fixed samples (A) as compared with the LifeAct experiments (B). This is likely explained by the shorter incubation time for the LifeAct experiments (45 minutes vs 3 hours) and phototoxic effects of the repeated imaging for live-cell experiments.

Erythrocyte antigen loss promoted by AMIS-inducing antibodies occurred through the transfer of RBC membrane fragments, consistent with trogocytosis

To determine whether the RBC membrane fluorescence observed in the macrophages was mediated by phagocytosis, macrophages were incubated with sensitized HOD-RBCs; however, no noticeable phagocytosis of the RBCs was observed (Figure 4A). Neither mouse pIgG anti–HEL nor anti-Duffy induced significant HOD-RBC phagocytosis (Figure 4B). In contrast, TER-119, an antibody capable of triggering macrophage phagocytosis of RBCs,32 induced significant phagocytosis of HOD-RBCs (Figure 4A-B).

Confocal microscopy of macrophages incubated with sensitized PKH67+HOD-RBCs revealed a substantial increase in the number of macrophages with internalized small green particles compared with macrophages incubated with nonsensitized RBCs (Figure 5A). The size of the ingested material triggered by the AMIS-inducing antibodies was not consistent with the size of a complete RBC. However, macrophages incubated with PKH67+HOD-RBCs sensitized with TER-119 revealed the presence of both small and large particles, indicating the concurrent occurrence of multiple processes (supplemental Figure 10A). Additionally, the recovered RBCs displayed evident loss of RBC antigens and membrane components (supplemental Figure 10B-C).

Visualization of the membrane uptake process by live confocal microscopy revealed that contact between macrophages and the sensitized PKH67+HOD-RBCs occurred over an extended period, resulting in the pulling and removal of small RBC membrane pieces and gradual membrane-fluorescence transfer from the RBC to the macrophages without any evidence of complete internalization of the RBC (Figure 5B; supplemental Videos 1 and 2). F-actin fluorescence was increased at the contact region between both cells, indicating that actin polymerization may be involved in the process. In contrast, macrophage phagocytosis of PKH67+HOD-RBCs sensitized with TER-119 showed a highly dynamic process of pseudopod extension and RBC entrapment, with successful phagocytosis completed within several minutes (supplemental Video 3), whereas internalization was not observed with nonsensitized RBC (supplemental Video 4).

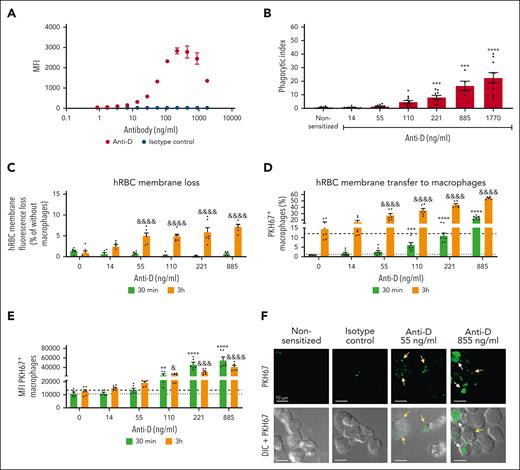

Anti-D induced transfer of human RBC membrane fragments to macrophages consistent with trogocytosis

To investigate whether anti-D itself could cause trogocytosis, experiments with anti-D-sensitized hRBCs and THP-1-CD16A macrophages were performed. RBCs sensitized with ≥110 ng/mL of anti-D (Figure 6A) showed significant phagocytosis (Figure 6B). Anti-D could, however, provoke substantial loss of RBC membrane fluorescence at doses as low as 55 ng/mL upon incubation with macrophages (Figure 6C). Moreover, a considerable number of macrophages displayed fluorescence uptake from the RBC membranes (Figure 6D), with an increasing uptake using higher concentrations of anti-D (Figure 6E). Confocal microscopy revealed that both high and low concentrations of anti-D induced trogocytosis (yellow arrows), whereas evident phagocytosis (white arrows) was primarily observed at higher anti-D concentrations (Figure 6F).

Anti-D triggers macrophage-mediated erythrocyte membrane loss consistent with macrophage trogocytosis. (A) Binding of RhD-specific pIgG (anti-D, WinRho SDF) to RhD+-human RBCs (RhD+ hRBCs) was performed by incubation of 5 × 106 RhD+ hRBCs with 50 μL of anti-D solutions yielding anti-D concentrations from 1770 ng/mL to 0.86 ng /mL (0.885-0.0004 IU), or with a mix of human IgG subclasses as an isotype control. Later, the RBCs were incubated with AF647-labeled anti–human IgG and analyzed by flow cytometry. MFI of the RBCs was determined. (B) THP-1-CD16A macrophages were stimulated with RhD+ hRBCs sensitized with anti-D, with the isotype control or nonsensitized for 30 minutes at 37°C and 5% CO2. External, nonphagocytosed RBCs were removed by hypotonic lysis. Brightfield microscopy images of macrophages from each condition were captured. The phagocytic index was calculated as the number of RBCs engulfed per 100 macrophages. Data represents the mean ± SEM of 4 independent experiments with the total number of data points per group equaling n = 5 to 11. (C) RhD+-human RBCs were fluorescently labeled with PKH67 (PKH67+ RhD+ hRBCs) and sensitized with different concentrations of anti-D as indicated. Nonsensitized PKH67+RhD+ hRBCs (0 ng/mL) or sensitized with isotype control were used as controls. Sensitized and nonsensitized PKH67+RhD+-hRBCs were incubated with or without THP-1-CD16A macrophages for 30 minutes and 3 hours at 37°C and 5% CO2. Later, RBCs were recovered from each condition and the residual external RBCs attached outside of macrophages were lysed. MFI of the PKH67 signal of the PKH67+RhD+-hRBC recovered after incubation in the presence vs absence of macrophages were analyzed by flow cytometry. The quantity of RBC membrane loss was measured as a percentage of the MFI of the PKH67 signal from RBCs that had been incubated with macrophages to the MFI of RBCs without macrophages. Data represent the mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments with 2 replicates per condition. (D-E) THP-1-CD16A macrophages incubated with nonsensitized vs sensitized RBCs were also analyzed by flow cytometry, and (D) the percentage of the PKH67+ macrophages and (E) the MFI of PKH67 signal in the PKH67+ macrophage gate was determined. The dotted and dashed lines represent background fluorescence of macrophages incubated with isotype control sensitized RBC at 30 minutes and 3 hours, respectively. (F) THP-1-CD16A macrophages were seeded on coverslips for 2 days. Later, macrophages were stimulated with PKH67+RhD+-hRBCs sensitized with anti-D at the indicated concentrations, nonsensitized, or sensitized with isotype control. After 3 hours of incubation, excess RBCs were washed away, and external RBCs were lysed followed by fixation. Images from each condition were taken on a Quorum multimodal imaging system (spinning disk confocal) at original magnification ×63 objective oil immersion (numerical aperture 1.47). Scale bar = 10 μm. Statistical analyses of the data represented in the graph of panel B were performed by Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn multiple comparisons post hoc test, by two-way ANOVA with Sidak multiple comparisons post hoc test for data in the graph of panel C, and Dunnett multiple comparisons post hoc test for the graph of panels D and E. Significant differences to the control group (nonsensitized) at 30 minutes and 3 hours are indicated with ∗ and & respectively. (∗P = .05; ∗∗P = .01; ∗∗∗P = .001; ∗∗∗∗P = .0001; &P = .05; &&&P = .001; &&&&P = .0001).

Anti-D triggers macrophage-mediated erythrocyte membrane loss consistent with macrophage trogocytosis. (A) Binding of RhD-specific pIgG (anti-D, WinRho SDF) to RhD+-human RBCs (RhD+ hRBCs) was performed by incubation of 5 × 106 RhD+ hRBCs with 50 μL of anti-D solutions yielding anti-D concentrations from 1770 ng/mL to 0.86 ng /mL (0.885-0.0004 IU), or with a mix of human IgG subclasses as an isotype control. Later, the RBCs were incubated with AF647-labeled anti–human IgG and analyzed by flow cytometry. MFI of the RBCs was determined. (B) THP-1-CD16A macrophages were stimulated with RhD+ hRBCs sensitized with anti-D, with the isotype control or nonsensitized for 30 minutes at 37°C and 5% CO2. External, nonphagocytosed RBCs were removed by hypotonic lysis. Brightfield microscopy images of macrophages from each condition were captured. The phagocytic index was calculated as the number of RBCs engulfed per 100 macrophages. Data represents the mean ± SEM of 4 independent experiments with the total number of data points per group equaling n = 5 to 11. (C) RhD+-human RBCs were fluorescently labeled with PKH67 (PKH67+ RhD+ hRBCs) and sensitized with different concentrations of anti-D as indicated. Nonsensitized PKH67+RhD+ hRBCs (0 ng/mL) or sensitized with isotype control were used as controls. Sensitized and nonsensitized PKH67+RhD+-hRBCs were incubated with or without THP-1-CD16A macrophages for 30 minutes and 3 hours at 37°C and 5% CO2. Later, RBCs were recovered from each condition and the residual external RBCs attached outside of macrophages were lysed. MFI of the PKH67 signal of the PKH67+RhD+-hRBC recovered after incubation in the presence vs absence of macrophages were analyzed by flow cytometry. The quantity of RBC membrane loss was measured as a percentage of the MFI of the PKH67 signal from RBCs that had been incubated with macrophages to the MFI of RBCs without macrophages. Data represent the mean ± SEM of 3 independent experiments with 2 replicates per condition. (D-E) THP-1-CD16A macrophages incubated with nonsensitized vs sensitized RBCs were also analyzed by flow cytometry, and (D) the percentage of the PKH67+ macrophages and (E) the MFI of PKH67 signal in the PKH67+ macrophage gate was determined. The dotted and dashed lines represent background fluorescence of macrophages incubated with isotype control sensitized RBC at 30 minutes and 3 hours, respectively. (F) THP-1-CD16A macrophages were seeded on coverslips for 2 days. Later, macrophages were stimulated with PKH67+RhD+-hRBCs sensitized with anti-D at the indicated concentrations, nonsensitized, or sensitized with isotype control. After 3 hours of incubation, excess RBCs were washed away, and external RBCs were lysed followed by fixation. Images from each condition were taken on a Quorum multimodal imaging system (spinning disk confocal) at original magnification ×63 objective oil immersion (numerical aperture 1.47). Scale bar = 10 μm. Statistical analyses of the data represented in the graph of panel B were performed by Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn multiple comparisons post hoc test, by two-way ANOVA with Sidak multiple comparisons post hoc test for data in the graph of panel C, and Dunnett multiple comparisons post hoc test for the graph of panels D and E. Significant differences to the control group (nonsensitized) at 30 minutes and 3 hours are indicated with ∗ and & respectively. (∗P = .05; ∗∗P = .01; ∗∗∗P = .001; ∗∗∗∗P = .0001; &P = .05; &&&P = .001; &&&&P = .0001).

Discussion

AMIS has been experimentally demonstrated with various cell types, including RBCs,8,13,31,38,39 platelets,40,41 bacteria, viruses, and vaccine antigens.42,43 Various hypotheses have been proposed to explain the AMIS mechanism, including RBC clearance, epitope masking/steric hindrance, FcγRIIB-mediated B-cell inhibition, immune deviation, cytokine effects, and antigen loss.4,6-8,13-16,44-46 Rapid clearance of RBCs has been widely considered the most likely mechanism for AMIS effects. In fact, several anti-D monoclonal antibodies have been developed based on their clearance capabilities; however, none of them have been as effective as donor-derived anti-D, and some have even led to the opposite effect, immune enhancement.11,47,48 Consequently, a better understanding of the mechanism(s) underpinning AMIS is required. Although RBC clearance remains popular, the focus of the AMIS effect in experimental models has recently shifted away from RBC clearance toward other mechanisms.44,45,49

Recent studies have demonstrated that RBC antigen loss is observed under AMIS conditions.14,15,17,18 In particular, Stowell and coworkers originally showed in mice that passive administration of anti-KEL sera followed by transfusion of transgenic mouse RBCs expressing human KEL led to successful AMIS against KEL in conjunction with the loss of detectable KEL on the RBCs.39 Mechanistic studies by Liu et al then found in this model that AMIS and antigen loss were not observed in mice lacking both Fcγ receptors and complement component 3, suggesting that AMIS and antigen loss potentially share a mechanistic pathway.14 RBC clearance, unfortunately, occurred under the same conditions as antigen loss, and both processes were impaired in the double-knockout mice.14 Using the HOD mouse model, we previously demonstrated that the ability of antibodies to target the OVA portion of the HOD antigen was more closely associated with its ability to promote antigen loss than RBC clearance15; however, the question of whether antigen loss vs RBC clearance contributes to the AMIS effect, still remained speculative.

In this study, we evaluated a spectrum of different antibodies, which has allowed us to address whether RBC clearance or antigen loss can be uncoupled from the antibodies’ AMIS-inducing activity. Several antibodies induced AMIS independent of their ability to mediate any detectable clearance of RBCs. Thus, RBC clearance is not a requirement for successful AMIS induction in this model. In contrast, all antibodies capable of inducing a strong AMIS effect caused significant in vivo loss of the HOD antigen. Consequently, to our knowledge, the results obtained here provide the first evidence supporting the role of antigen loss as a mechanism of action of AMIS induced by antibodies that do not cause RBC clearance.

Antigen loss mediated by antibodies has long been observed in a variety of systems.50-53 In the context of RBCs, studies have proposed a role for monocytes or macrophages;17 however, the mechanism through which antigen loss is mediated by these cells has remained poorly understood. Potential mechanisms include direct cleaving of the antigen from the RBC, induction of RBC surface proteases to cleave the antigen,54 vesiculation of RBCs,55 internalization of the antigen within the RBC, or, as demonstrated here, uptake of the antigen by the macrophage through trogocytosis. Thus far, RBCs exhibiting antigen loss under AMIS conditions have not been shown to harbor the surface antigen internally.14,17,18 Although some RBC antigens, such as the distal portion of the HOD molecule (HEL), are susceptible to loss via protease-mediated degradation,17,18 matrix metalloproteinase inhibition did not significantly affect the degree of HEL antigen loss by AMIS-inducing antibodies in vitro in the presence of macrophages.

Trogocytosis is a mechanism that allows for the uptake of the antibody and the antigen, including the transfer of plasma membrane pieces, between acceptor and donor cells.56 This process has been observed for a variety of immune cells22-25 and is thought to play a role in antigen presentation, immune surveillance, and cell-to-cell communication. Here, we have demonstrated that AMIS-inducing antibodies promote antigen loss accompanied by a loss of plasma membrane lipids (indicated by PKH26), suggesting a process with these key attributes of trogocytosis occurring in vivo. To model this mechanism in vitro, selected AMIS-inducing antibodies specific to different portions of the HOD antigen were examined for in vitro antigen loss, RBC membrane loss, and RBC membrane transfer to macrophages. RBCs incubated with AMIS-inducing antibodies in the absence of macrophages did not undergo any antigen loss or RBC membrane loss. In contrast, the same antibodies promoted antigen loss and RBC membrane loss in the presence of macrophages without inducing phagocytosis. Despite the absence of phagocytosis, under the same conditions where antigen loss and RBC membrane loss were observed in vitro, we also observed transfer of small membrane fragments from the RBCs to the macrophages via a nibbling process consistent with trogocytosis. Remarkably, even at low concentrations of 55 ng/mL, when phagocytosis was minimal or absent, anti-D still prompted membrane loss in human RBCs, a hallmark of trogocytosis. Intriguingly, this concentration closely corresponds to an estimated final anti-D level of ∼66 ng/mL in an RhD-negative pregnancy following a standard dose of 300 μg (or 1500 IU) of anti-D, based on a 5-L maternal blood volume. At this low anti-D dose, our data are consistent with a preference for triggering trogocytosis over phagocytosis. Thus, under AMIS conditions with anti-D, trogocytosis, rather than phagocytosis, could be the predominant mechanism activated by anti-D.

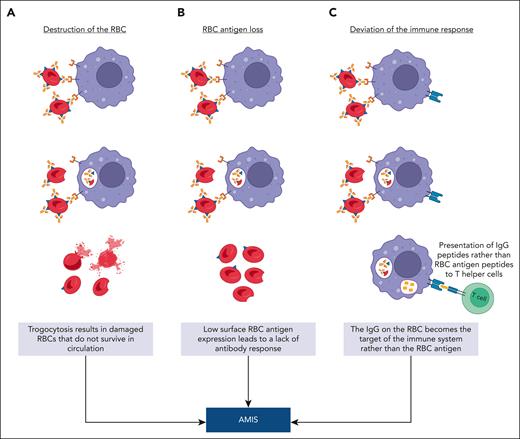

A question yet to be answered is “how might trogocytosis contribute to the mechanism of AMIS?” We present 3 potential hypotheses (Figure 7). In cancer therapy, repeated trogocytosis of the same cell can lead to the death or lysis of the antibody-opsonized cancer cell.24 As a first hypothesis, it is possible that pronounced RBC trogocytosis contributes to RBC clearance through extensive RBC damage (Figure 7A). As a second potential hypothesis, trogocytosis simply removes the antigen from the RBC below the threshold required for a successful humoral immune response57 (Figure 7B).

Hypotheses explaining AMIS-induced RBC antigen loss via trogocytosis. (A) Destruction of the RBC: IgG-sensitized RBCs interact with immune cells (macrophages, B cells, neutrophils, and dendritic cells), which strip the antigen-antibody complex from the surface of the RBC along with RBC membrane resulting in extensive cell damage. (B) RBC antigen loss: IgG-sensitized RBCs undergo trogocytosis-induced antigen loss by an immune cell (macrophages, B cells, neutrophils, and dendritic cells), resulting in circulating RBCs with an antigen level below that needed for an immune response. (C) Deviation of the immune response: IgG-sensitized RBCs engage with an antigen presenting cell (macrophages, dendritic cells, or B cells), resulting in the internalization of the IgG-antigen complex with peptides from both the antigen and IgG, which compete for display on major histocompatibility complex class II. Under AMIS conditions, the IgG peptides preferentially undergo antigen processing and presentation to T helper cells. This figure was created with BioRender.com.

Hypotheses explaining AMIS-induced RBC antigen loss via trogocytosis. (A) Destruction of the RBC: IgG-sensitized RBCs interact with immune cells (macrophages, B cells, neutrophils, and dendritic cells), which strip the antigen-antibody complex from the surface of the RBC along with RBC membrane resulting in extensive cell damage. (B) RBC antigen loss: IgG-sensitized RBCs undergo trogocytosis-induced antigen loss by an immune cell (macrophages, B cells, neutrophils, and dendritic cells), resulting in circulating RBCs with an antigen level below that needed for an immune response. (C) Deviation of the immune response: IgG-sensitized RBCs engage with an antigen presenting cell (macrophages, dendritic cells, or B cells), resulting in the internalization of the IgG-antigen complex with peptides from both the antigen and IgG, which compete for display on major histocompatibility complex class II. Under AMIS conditions, the IgG peptides preferentially undergo antigen processing and presentation to T helper cells. This figure was created with BioRender.com.

Alternatively, trogocytosis may serve as a component of the immune recognition pathway, wherein the antigen, along with its accompanying IgG in the context of AMIS, is selectively captured and presented to the immune system (Figure 7C). Evidence challenging the notion that the RBC antigen simply vanishes before immune recognition was offered by studies showing that an immune response does indeed occur in AMIS, but it is specifically targeted against the AMIS-inducing IgG rather than the RBC antigen itself.8 This effect was also seen using diphtheria/tetanus vaccines in the absence vs presence of anti-tetanus IgG.8 Furthermore, work by Bergström et al showed that under AMIS conditions, an immune response against IgG can occur in germinal centers.7 Our favored third hypothesis posits that within the context of AMIS, the role of trogocytosis is to channel the antigen into an antigen-processing pathway. In this scenario, the focus of the immune response shifts from the RBC antigen to the AMIS-inducing antibody itself. Further experiments are needed to define which of these hypotheses or others could be correct.

In summary, our research elucidates the pivotal role of trogocytosis in antigen loss mediated by AMIS antibodies. These insights recommend that in the design of anti-D monoclonals for prophylactic use, the capacity to induce trogocytosis-driven antigen loss should be a key consideration, not merely the ability for RBC clearance. In the future, it will be essential to investigate how trogocytosis mechanisms modulate the immune response to RBC antigens.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank James Zimring for providing the transgenic HOD mouse model and the HEL-specific monoclonal antibodies 4B7 and 2F4. The authors also thank George Segal and Donald Branch for the helpful discussion and Melika Loriamini for providing technical and intellectual guidance on blood film preparation and microscopy. The authors thank colleagues Joan Legarda, Ramsha Khan, Gurleen Kaur, Dooyon (Kevin) Won, Yaima Tundidor, and Alequis Pavon Oro as well as the Keenan Research Centre for Biomedical Science Core Facilities and Vivarium Staff at St Michael’s Hospital.

This study was supported by research funding from Canadian Blood Services through a postdoctoral fellowship to Y.C.-L. and a Canadian Blood Services Intramural Research grant to A.H.L.

Authorship

Contribution: Y.C.-L. and A.H.L. conceived the study and wrote the manuscript; Y.C.-L. and P.A.A.N. designed experiments; Y.C.-L., P.A.A.N., D.M., L.G.G., H.W., and Y.S. performed experiments, Y.C.-L., P.A.A.N., D.M., L.G.G., H.W., and A.H.L. analyzed and interpreted data; Y.C.-L., P.A.A.N., and L.G.G. prepared the figures; Y.C.-L., P.A.A.N., H.W., L.G.G., and A.H.L. edited the manuscript; Y.S. provided vital reagents; and A.H.L. obtained grant funding.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Alan H. Lazarus, Canadian Blood Services, Keenan Research Centre for Biomedical Science of St Michael’s Hospital, University of Toronto, St Michael’s Hospital, 209 Victoria St, Toronto, ON M5B 1T8, Canada; email: alan.lazarus@unityhealth.to.

References

Author notes

Data sets and protocols are available to other investigators on request from the corresponding author, Alan H. Lazarus (alan.lazarus@unityhealth.to).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal