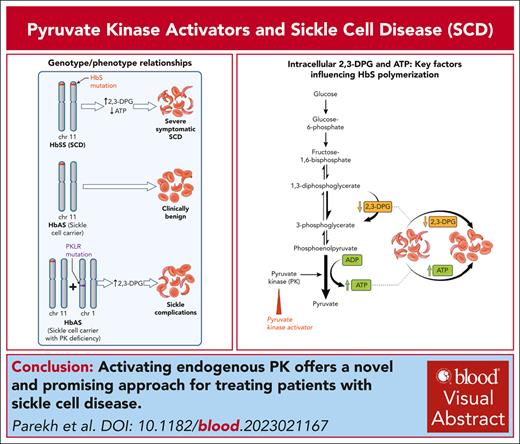

Visual Abstract

Pyruvate kinase (PK) is a key enzyme in glycolysis, the sole source of adenosine triphosphate, which is essential for all energy-dependent activities of red blood cells. Activating PK shows great potential for treating a broad range of hemolytic anemias beyond PK deficiency, because they also enhance activity of wild-type PK. Motivated by observations of sickle-cell complications in sickle-trait individuals with concomitant PK deficiency, activating endogenous PK offers a novel and promising approach for treating patients with sickle-cell disease.

Introduction

Glycolysis and pyruvate kinase (PK)

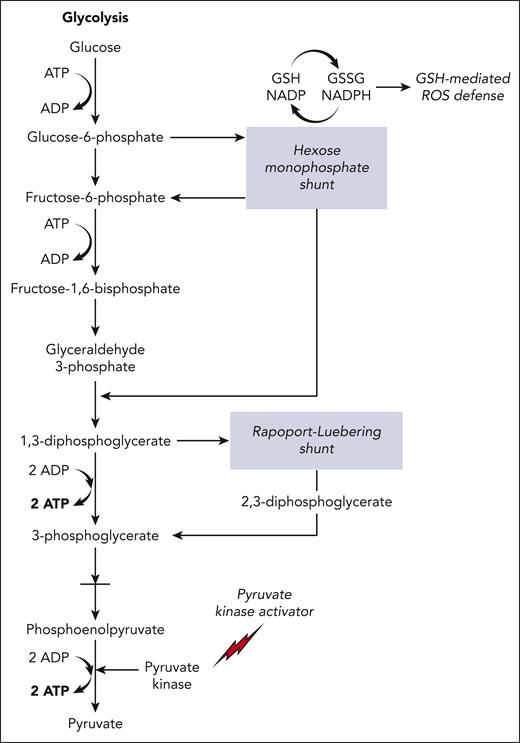

Red blood cells (RBCs) depend on glycolysis for their sole source of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is essential for all energy-dependent activities and cellular integrity.1,2 PK (red-cell isotype gene PKLR, protein PK) is a key enzyme in glycolysis; its activity regulates the rate of the second ATP-generating step in the glycolytic pathway, in which phosphoenolpyruvate is converted to pyruvate (Figure 1).3 In addition to reducing intracellular ATP levels, decreased PK activity leads to a build-up of the upstream glycolysis substrates, especially 2,3-diphosphoglycerate (2,3-DPG). Increased 2,3-DPG promotes hemoglobin S (HbS) polymerization by shifting the oxygen-dissociation curve to the right, by stabilizing the sickle fiber and by decreasing the intracellular pH.4-6 Indeed, deficiency and/or dysfunctional PK enzymes caused by mutations in PKLR leads to increased 2,3-DPG and reduced ATP, shortening of RBC lifespan, and a phenotype of chronic hemolytic anemia.7,8

Schematic overview of the glycolytic pathway in RBCs. 2,3-DPG (2,3-diphosphoglycerate) is generated using the Rapoport-Luebering shunt, a metabolic bypass. Another metabolic bypass is the hexose monophosphate shunt, a primary source of antioxidants (glutathione–mediated reactive oxygen species defence) in RBCs. PK activators (mitapivat or etavopivat) enhance activity of PK, increasing the glycolytic flux, generating ATP while reducing 2,3-DPG levels, both of which are antisickling effects. The glycolytic pathway invests 2 molecules of ATP to generate 4 molecules of ATP, a net gain of 2 ATP per unit of glucose. GSH, glutathione; GSSG, glutathione disulfide; NADP, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate; NADPH, reduced NADP. Figure created by Alan Hoofring, National Institutes of Health.

Schematic overview of the glycolytic pathway in RBCs. 2,3-DPG (2,3-diphosphoglycerate) is generated using the Rapoport-Luebering shunt, a metabolic bypass. Another metabolic bypass is the hexose monophosphate shunt, a primary source of antioxidants (glutathione–mediated reactive oxygen species defence) in RBCs. PK activators (mitapivat or etavopivat) enhance activity of PK, increasing the glycolytic flux, generating ATP while reducing 2,3-DPG levels, both of which are antisickling effects. The glycolytic pathway invests 2 molecules of ATP to generate 4 molecules of ATP, a net gain of 2 ATP per unit of glucose. GSH, glutathione; GSSG, glutathione disulfide; NADP, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate; NADPH, reduced NADP. Figure created by Alan Hoofring, National Institutes of Health.

Background

PK activators as a new class of therapeutics

Targeting endogenous PK activity and regulation of cell metabolism is not unique to hemolytic anemias and was first exploited in the development of cancer therapy.9,10 The target in cancer treatment is to inhibit or downregulate PKM2 activity10 on the basis of reprogramming cancer cell metabolism to reduce tumor growth. The target in hemolytic anemias, however, is to increase activity of PK based on increasing ATP or decreasing 2,3-DPG, and PK activators were originally developed for treating patients with inherited PK deficiency (PKD) caused by mutations in PKLR. Mitapivat (AG-348; Agios Pharmaceuticals Inc, Cambridge, MA) is a first-in-class oral, allosteric activator of PK; it binds at the dimer-dimer interface of PK and activates the enzyme by stabilizing its more active conformation.11 In a phase 3 randomized, placebo-controlled study (ACTIVATE, NCT03548220) of nontransfusion dependent adult patients with PKD, mitapivat improved anemia accompanied by reduced markers of hemolysis.12 Mitapivat also significantly reduced transfusion burden in 10 of 27 transfusion-dependent adults with PKD in an open label, phase 3 study (ACTIVATE-T, NCT03559699).13 In both studies, mitapivat was well-tolerated with an acceptable safety profile. In 2022, mitapivat (renamed Pyrukynd) was approved in the United States by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), in the European Union and in Great Britain for the treatment of anemia in adults with PKD.

Although PK activators were under clinical development for PKD, preclinical animal and human studies suggested the possibility of using the drug to treat other hemolytic anemias. In both mice and healthy adults with wild-type PK, mitapivat increased intracellular ATP while decreasing 2,3-DPG levels in a dose-dependent manner consistent with in vivo activation of PK.11,14 Studies in a mouse model with β-thalassemia showed that mitapivat increased ATP, reduced ineffective erythropoiesis and improved anemia, providing the rationale for a clinical study in patients with thalassemia.15 In a phase 2, open-label, multicenter study of patients with non-transfusion-dependent α- and β-thalassemia (NCT03692052) mitapivat significantly improved anemia in 16 of the 20 patients.16 Two phase 3 clinical studies of mitapivat in non-transfusion-dependent (ENERGIZE, NCT04770753) or transfusion-dependent (ENERGIZE-T, NCT04770779) thalassemias are ongoing.

PK activation and sickle cell disease

Enhancing PK activity as a treatment for SCD

Vaso-occlusion, the presumed cause of episodic acute pain, and chronic hemolytic anemia are the 2 key hallmarks of sickle-cell disease (SCD) that underlie the cumulative organ damage, morbidity, and premature mortality.17 The pathology is initiated by polymerization of HbS and distortion (“sickling”) of RBCs.17 HbS polymerizes only when deoxygenated, and a key factor influencing HbS oxygenation is the intracellular concentration of 2,3-DPG. 2,3-DPG preferentially binds to the low-affinity T conformation, thus promoting HbS polymerization and further promotes polymerization by stabilizing the sickle fiber and decreasing the intraerythrocyte pH.4,5 2,3-DPG levels in blood of patients with SCD are significantly higher than healthy subjects,18 and reducing 2,3-DPG had been proposed as a potential antisickling therapy.5,6 The importance of 2,3-DPG in the pathophysiology of SCD is exemplified in 2 highly relevant case reports,19,20 in which 2 individuals with sickle-cell trait (HbAS), a normally clinically benign condition,21 had a typical phenotype of SCD. Both individuals had also coinherited mutations in PKLR with reduced PK activity, and 2,3-DPG levels assessed in 1 individual were markedly increased.19

The observation that PK levels could be a modifier of SCD prompted a candidate gene-association study. In 2 SCD cohorts, 1 adult and the other pediatric, PKLR intron 2 variants were associated with acute sickle pain and affected PKLR expression.22 The same “PKLR-risk variants” were also associated with reduced red-cell ATP levels providing a biochemical basis for the genetic association with acute sickle pain.23 Thus, enhancing PK activity, which increases ATP levels and decreases 2,3-DPG levels in sickle RBCs, presented a very attractive therapeutic antisickling strategy. Moreover, ex vivo studies on RBCs of patients with SCD showed that mitapivat restored PK activity and PK thermostability, reduced 2,3-DPG, increased ATP, and increased ATP to 2,3-DPG ratio.24 Studies in mouse models of SCD recapitulated most of the effects of PK activation in humans.25,26

Update on clinical trials of PK activators for SCD

Proof-of-concept for activating PK as a viable therapeutic approach was established in a phase 1, open-label multiple-dose ascending study (NCT04000165)27 and a phase 2 open-label study (ESTIMATE, NL8517).28 In both studies, mitapivat was well-tolerated, with an acceptable safety profile observed in previous studies.12,13,16 Patients had increased Hb levels, decreased hemolytic markers, increased ATP, and decreased 2,3-DPG levels with decreased sickling. Both studies are followed by evaluation of safety and efficacy of mitapivat as a long-term maintenance therapy for patients with SCD in 2 centers (NCT04610866 and ESTIMATE, NL8517).

A phase 2/3, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of mitapivat in patients with SCD (RISE UP, NCT05031780) was launched in 2022. The phase 2 portion has been completed and RISE UP phase 3 will follow using the mitapivat dose selected from phase 2 for a 52-week period.

Two other orally administered allosteric activators of PK are under clinical development, etavopivat (FT-4202, Forma Therapeutics [Watertown, MA]) and AG-946 (Agios Pharmaceuticals Inc). Preclinical and phase 1 studies of etavopivat demonstrated enhanced glycolytic activity, safety, and efficacy in both healthy volunteers and patients with SCD.29-31 HIBISCUS (NCT04624659) is a phase 2/3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study of etavopivat in adults and adolescents with SCD. Etavopivat is also being evaluated in a phase 2 open-label study (NCT04987489) for its efficacy in reducing RBC transfusion requirements in patients with SCD or other refractory anemias. AG-946 is currently undergoing a phase 1 open-label, dose-ascending study for assessment of safety and tolerability in healthy volunteers and subjects with SCD (NCT04536792). Table 1 summarizes the ongoing clinical studies of PK activators in SCD.

Ongoing clinical studies of PK activators in SCD

| Medication . | Clinicaltrials.gov identifier . | Study design . | Study population (age) . | N . | Anticipated completion . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mitapivat | NCT04610866 | Ph 1, open-label, single center | HbSS (18-70) | 15 | 2/2028 |

| Mitapivat | NL8517 (The Netherlands) EudraCT 2010-003438-18 (ESTIMATE) | Ph 2, open-label, single center | HbSS or HbSβ0 (≥18) | 10 | |

| Mitapivat | NCT05031780 EudraCT 2021-001674-34 (RISE UP) | Ph 2/3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter | SCD, any (≥16) | 69 (Ph 2) 198 (Ph 3) | 11/2029 |

| AG-946 | NCT04536792 | Ph 1, randomized, double-blind (healthy volunteers), open-label (SCD), multicenter | Healthy volunteers SCD, any (18-70) | 64 | 3/2024 |

| Etavopivat | NCT04624659 (HIBISCUS) | Ph 2/3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter | SCD, any (12-65) | 344 | 12/2026 |

| Etavopivat | NCT04987489 | Ph 2, open-label, multiple-cohort, multicenter | Cohort A: SCD, any, on chronic transfusions (12-65) Cohort B: thalassemia, any, on chronic transfusions (12-65) Cohort C: thalassemia, any, nontransfused (12-65) | 60 | 7/2025 |

| Medication . | Clinicaltrials.gov identifier . | Study design . | Study population (age) . | N . | Anticipated completion . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mitapivat | NCT04610866 | Ph 1, open-label, single center | HbSS (18-70) | 15 | 2/2028 |

| Mitapivat | NL8517 (The Netherlands) EudraCT 2010-003438-18 (ESTIMATE) | Ph 2, open-label, single center | HbSS or HbSβ0 (≥18) | 10 | |

| Mitapivat | NCT05031780 EudraCT 2021-001674-34 (RISE UP) | Ph 2/3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter | SCD, any (≥16) | 69 (Ph 2) 198 (Ph 3) | 11/2029 |

| AG-946 | NCT04536792 | Ph 1, randomized, double-blind (healthy volunteers), open-label (SCD), multicenter | Healthy volunteers SCD, any (18-70) | 64 | 3/2024 |

| Etavopivat | NCT04624659 (HIBISCUS) | Ph 2/3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter | SCD, any (12-65) | 344 | 12/2026 |

| Etavopivat | NCT04987489 | Ph 2, open-label, multiple-cohort, multicenter | Cohort A: SCD, any, on chronic transfusions (12-65) Cohort B: thalassemia, any, on chronic transfusions (12-65) Cohort C: thalassemia, any, nontransfused (12-65) | 60 | 7/2025 |

Possible concerns for the use of PK activators in SCD based on its mechanism

Bunn has recently stressed the importance of understanding the underlying physiology in the treatment of anemia, focusing on the importance of Hb’s oxygen delivery function.32 His discussion is quite relevant to the issue of PK activation changing oxygen affinity of HbS by decreasing 2,3-DPG levels. 2,3-DPG preferentially binds to the low-affinity T conformation of Hb, shifting the oxygen-dissociation curve to the right, thereby allowing a higher fraction of oxygen to be off-loaded from Hb in the tissues at every oxygen pressure. Indeed, the rightward shift in Hb oxygen dissociation explains why patients with PKD can tolerate relatively low Hb levels.8,32 We must consider the possibility that the increase in Hb oxygen affinity from reduced 2,3-DPG (from activating PK), while decreasing HbS polymerization and sickling, may compromise off loading of oxygen, which probably occurs with voxelotor.32 There is, however, an essential difference between the mechanisms of increasing Hb oxygen affinity by voxelotor and PK activators.32 Voxelotor binds very tightly to the nonpolymerizing R conformation of HbS,33,34 a conformation that off loads very little oxygen, effectively eliminating drug-bound Hb from performing an oxygen delivery function.35 Consequently, although the FDA approved the drug because of the increased Hb levels, the functioning levels of Hb are actually decreased. In spite of the reduced sickling by voxelotor, the net result of treatment with this drug is predicted not to increase overall oxygen delivery and, therefore, to result in no decrease in vaso-occlusive episodes,35 as borne out in clinical studies.32,36-38 In contrast, oxygen dissociation and binding of 2,3-DPG to HbS is rapid and, at the decreased 2,3-DPG levels found with activating PK, results in a much smaller left shift of the oxygen-dissociation curve compared with voxelotor and, therefore, a much smaller decrease in oxygen delivery.27,35,39 Moreover, lowering 2,3-DPG levels is accompanied by 3 other factors expected to reduce sickling. The HbS fiber is destabilized from a decrease in 2,3-DPG from 2 effects: an increase in intracellular pH40-42 and direct destabilization of the fiber,5 presumably by altering the tertiary structure of the T conformation.43 A third factor is the decrease in mean cellular Hb concentration from reduced 2,3-DPG, which can have a marked effect on sickling by increasing the delay time.6,44-46

In addition to reducing 2,3-DPG levels, there are 2 additional beneficial effects from the increased ATP levels. ATP is essential for maintenance of RBC hydration and membrane integrity1,47,48 and may also reduce ineffective erythropoiesis49 as shown in mitapivat treatment of mice with β-thalassemia.15 A second relates to the proposal that increased phosphorylation of band 3 (Tyr-P-Bd3) of the sickle RBC membrane disrupts interaction with the RBC ankyrin-spectrin-actin cytoskeleton,50-53 increasing hemolysis and triggering multiple processes that contribute to vaso-occlusion.54 Sickle RBCs have markedly increased Tyr-P-Bd354,55 and activating endogenous PK significantly reduced Tyr-P-Bd3 of the sickle RBCs as observed in a phase 1 dose-ascending study of mitapivat.27,56 These findings support the improved RBC integrity and ability of the RBCs to withstand deformational changes in response to shear stress, osmotic pressure, and decreasing oxygen tension.57

Other concerns of PK activators in SCD

It has been suggested that PK activators could affect the hexose monophosphate pathway (HMP) (Figure 1), the sole route for recycling nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate, compromising ability of RBCs to combat oxidative stress.58 On the contrary, activating PK allows for increased glucose uptake and enhanced shunt to HMP.2 In a β-thalassemia mouse model, mitapivat improved oxidative stress by increasing glutathione to glutathione disulfide ratio, suggesting that the HMP shunt is increased by mitapivat.15 Another concern is withdrawal hemolysis when mitapivat is abruptly discontinued59; in our experience, this appears patient dependent. Drug tapering mitigates this risk27 but nonetheless, all patients should be fully informed of the risk and medication adherence reinforced when considering initiation of mitapivat.

Conclusion and future direction

SCD is a leading cause of mortality, morbidity, and health disparity worldwide.60 Current pharmacologic interventions include approaches to increase fetal Hb, reduce vascular adhesion, or increase Hb oxygen affinity to decrease polymerization.61,62 Hydroxyurea, first approved for SCD by the FDA in 1998, has been shown to reduce acute pain and other sickle complications and remains the mainstay of drug treatment today,63 however its efficacy and tolerance are variable.64 Voxelotor, approved by the FDA in 2019, increases the oxygen affinity of sickle Hb. Although limiting hemolysis, the drug has no significant effect on the frequency or severity of vaso-occlusive events.36,37 There are 2 other FDA-approved medications that reduce the frequency of pain crises, that is, crizanlizumab which reduces red-cell adhesion, and l-glutamine which reduces oxidative stress.61,65 Currently, the only readily available curative option for SCD is allogeneic hemopoietic stem cell transplantation.66 Curative options involving gene addition (lovotibeglogene autotencel) of an antisickling Hb variant and genetic editing (exagamglogene autotemcel) of BCL11A67 were approved by the FDA in December 2023 but these will be limited by cost, resources, and/or location.68

The unmet need for more effective drugs to treat SCD has prompted an increasing number of agents under clinical development (https://clinicaltrials.gov). The recent discovery of over 100 new antisickling compounds from a phenotypic screen of the Scripps ReFrame drug repurposing library69 should add to this clinical development pipeline. Activating the RBC’s endogenous PK and restoring RBC metabolism breaks new ground and offers promise in the treatment of SCD. However, its efficacy in improving anemia, reducing pain and fatigue, and improvement in quality of life await data from the ongoing multicenter phase 2/3 studies of mitapivat and etavopivat. If these drugs do turn out to be successful therapies, a major problem that will have to be addressed is the high cost to the patient, especially for those living in underresourced regions, such as sub-Saharan Africa and areas of endemicity in India.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Anna Conrey (National Institutes of Health [NIH], National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [NHLBI]) for her help in preparation of Table 1 and Julia Xu (Pittsburgh University Medical School) for her input on the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Division of Intramural Research of the NIH, NHLBI and the NIH, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease.

Authorship

Contribution: D.S.P. wrote the first draft of the manuscript; S.L.T. and W.A.E. wrote and edited the manuscript; and all authors reviewed the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: S.L.T. and W.A.E. received mitapivat from Agios Pharmaceuticals for laboratory and clinical studies at the National Institutes of Health and exchanged information with Agios staff as part of a cooperative research and development agreement but received no research funds or honoraria from Agios. D.S.P. declares no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Swee Lay Thein, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, Building 10-CRC, Room 6S241, 10 Center Dr, Bethesda, MD 20892; email: sl.thein@nih.gov.

References

Author notes

Data are available on request to corresponding author, Swee Lay Thein (sl.thein@nih.gov).

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal