In this issue of Blood, Thompson et al report on the very-long–term follow-up of a phase 2 study of fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab (FCR) as initial therapy for young, fit patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).1

When helping young, fit patients with CLL to decide on initial therapy, a common question I get is: “What would you choose, doc?” A few years ago, my answer to this question for patients with mutated immunoglobulin variable heavy chain (IGHV-M) CLL was fairly straightforward—FCR. We have known for several years that about half of patients with IGHV-M CLL will have durable remission with FCR with only 6 months of therapy.

Over the last few years, new developments have led me to rethink my answer to this question. First, there was the COVID-19 pandemic and concerns that myelosuppression from FCR would impair immune response to vaccination and to infection. Then came a series of trials that chiseled cracks in the foundation that held up FCR as a standard of care. The US ECOG 1912 trial demonstrated not only a progression-free survival (PFS) benefit with continuous therapy with the oral Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor (BTKi) ibrutinib plus rituximab over FCR in young, fit patients (even in the subgroup with IGHV-M), but also an overall survival benefit at 5 years of follow-up.2 And the GAIA/CLL13 trial recently reported similar 3-year PFS between FCR and a time-limited 1-year course of a chemotherapy-free regimen of the oral B-cell lymphoma/leukemia 2 inhibitor venetoclax plus obinutuzumab (VO) in patients with IGHV-M CLL.3

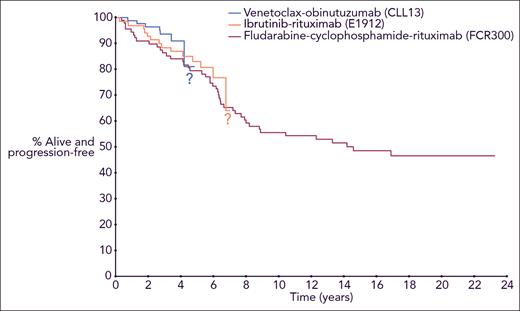

Although these results with targeted therapies are promising, the follow-up for these studies is short for a disease like CLL, which has a long natural history. This new report by Thompson et al reminds us that for young, fit patients with CLL, we need to consider their outcomes not only at 5 years after starting therapy but also at 20 years and beyond. With a median follow-up of 19 years, they report a median PFS for patients with IGHV-M CLL of 14.6 years. Disease progression beyond 10 years was uncommon, suggesting that some patients had “functional cure” of their CLL; however, a 6.3% cumulative risk of therapy-related myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS)/acute myeloid leukemia (AML) was observed. Thanks to the diligence of the group at MD Anderson, this report helps us to counsel young patients with CLL about their likely outcomes over the next 2 decades if they choose FCR as initial therapy. How will the outcomes of initial therapy with continuous ibrutinib or time-limited VO compare with FCR at 20 years? Although we are optimistic about the durability of remissions achieved with long-term sequential use of targeted therapies, our answer to that important question today is that we do not know, because follow-up with the targeted therapies is not nearly long enough (see figure).

PFS for younger, fit patients with IGHV-M CLL from 3 frontline treatment regimens, with curves from the different trials superimposed in a single Kaplan-Meier plot. Professional illustration by Somersault18:24.

PFS for younger, fit patients with IGHV-M CLL from 3 frontline treatment regimens, with curves from the different trials superimposed in a single Kaplan-Meier plot. Professional illustration by Somersault18:24.

Given the remarkably long remissions observed with FCR, recent studies have investigated ways to build on this efficacy. We found that the addition of ibrutinib to FCR for 6 months followed by 2 years of ibrutinib maintenance led to bone marrow undetectable minimal residual disease (BM-uMRD) in 84% of patients, with equivalent results irrespective of IGHV status, raising the prospect of long-term remission with this FCR-based therapy even in IGHV-unmutated patients.4 Similarly deep responses were also seen in studies of ibrutinib with FC-obinutuzumab,5,6 and these innovative trials also explored abbreviating the number of chemotherapy courses to reduce toxicity. Randomized studies comparing a BTKi plus FC plus anti-CD20 regimen to targeted therapy in young CLL patients would be informative.

Promising regimens combining targeted therapies to achieve deep, durable remissions without the need for chemotherapy are also in development. Ibrutinib plus venetoclax (with or without obinutuzumab) has demonstrated high rates of BM-uMRD,7 though characteristic toxicities of ibrutinib were observed, and the future development of this regimen in the United States is uncertain. Phase 2 studies of combinations of more specific covalent BTKi, including acalabrutinib with VO (AVO trial)8 and zanubrutinib with VO (BOVen trial),9 have also demonstrated high BM-uMRD rates, with excellent tolerability. The fully accrued CL-311/AMPLIFY phase 3 trial of AVO vs AV vs FCR/BR (NCT03836261) will eventually help us to understand how regimens like this compare with FCR.

It will be difficult for any single targeted therapy regimen on its own to beat the median PFS of 14.6 years reported by Thompson et al with FCR for IGHV-M CLL. Yet as data on the targeted therapies continue to mature, there is cause for optimism. For example, a median PFS was not reached at 5 years with VO in the CLL14 study, and patients with IGHV-M had particularly durable responses.10 If patients can be successfully retreated with VO after progression, that could be a game changer, with median time to next class of therapy approaching that seen with FCR. Prospective data on VO retreatment will eventually be generated from the ongoing phase 2 ReVenG trial (NCT04895436). With other promising targeted therapies on the horizon such as noncovalent BTKi and chimeric antigen receptor T cells, we may eventually have enough targeted therapies to keep young patients with CLL in remission for decades without the need for FCR.

So now when I sit with a young patient with CLL and he or she asks what I would choose for frontline therapy, the answer is less clear than it used to be. Based on the very-long–term data from Thompson et al, FCR remains a reasonable choice for young, fit patients with IGHV-M CLL, particularly in countries where access to frontline targeted therapies is limited. But given the risks of secondary MDS/AML, prolonged myelosuppression, and infectious complications, my usual answer now is that I would choose a targeted therapy regimen and hope that we will continue to develop new approaches to add to the impressive array of novel therapies we already have available for patients with CLL. If past performance is a predictor of future results in CLL, then the progress of the last decade bodes well for the therapeutic advances we are likely to continue to make in the next decade and beyond.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: M.S.D. declares institutional research funding from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Ascentage Pharma, Genentech, MEI Pharma, Novartis, Surface Oncology, and TG Therapeutics; and personal consulting income from AbbVie, Adaptive Biosciences, Ascentage Pharma, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, BMS, Eli Lilly, Genentech, Genmab, Janssen, Merck, Mingsight Pharmaceuticals, Nuvalent, Secura Bio, TG Therapeutics, and Takeda.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal